In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the number of countries with a semi-presidential form of government rose sharply. There are currently more than fifty such countries, spread across Western and Eastern Europe as well as Asia and Africa.Footnote 1 Found in many transitional countries and nascent democracies, semi-presidentialism has drawn interest among scholars, particularly in connection to the prospects for democracy’s consolidation and duration.Footnote 2

Although the term semi-presidentialism first appeared in the 1970s, its definition is still debated.Footnote 3 Consequently, lists of semi-presidential countries have varied considerably between studies.Footnote 4 In the late 1990s, Robert ElgieFootnote 5 defined semi-presidentialism as a system with a popularly elected president and a prime minister whose government is accountable to a parliament. Based on a series of formal and institutional measures, Elgie’s definition yields a clear-cut sample of semi-presidential countries, and it quickly gained prominence in the field.Footnote 6

However, Elgie’s definition has a drawback for empirical analysis: it yields a very diverse set of semi-presidential countries, particularly in terms of the degree of presidential power. Parallel with Elgie’s definition, therefore, a subcategorization of semi-presidential systems – focused on the degree of presidential power to dismiss a cabinet – gained acceptance as well.Footnote 7 This subcategorization divides semi-presidential systems into either premier-presidential or president-parliamentary regimes.

Shifting research topics can be added to the differing use of definitions. The varied definitions have been carefully illuminated in three review articles.Footnote 8 ElgieFootnote 9 describes the development as one characterized by three waves, whereby the main research focus has gradually shifted from definitional debates to aspects of democratic survival, and from there to the influence and role of the president.

Notwithstanding these variations, the influence of a few seminal articles has afforded a degree of commonality within the field.Footnote 10 Juan Linz’sFootnote 11 argument, to the effect that both presidentialism and semi-presidentialism contain inherent institutional perils, has ‘established the terms of the debate’. Several scholars have added to his line of argument with studies of the dangers associated with semi-presidential constitutions.Footnote 12 Others have challenged Linz, stressing the mixed performance of semi-presidential countries as well as the potential for power sharing and flexible executive relations afforded by this form of government, especially in its premier-presidential variant.Footnote 13

Semi-presidential studies feature differing definitions, varying country samples and shifting research topics. Yet the field has evolved from its initial domination by a set of ideas largely anchored in Linz’s argument for parliamentarism and against presidentialism. Petra Schleiter and Edward Morgan-JonesFootnote 14 argue that the last decade has seen ‘a rapid broadening of the research agenda beyond Linz’s concern with the adverse effects of presidents on democratic stability’. In this article, however, we question whether the field has actually shifted its theoretical lens and moved away from Linz in this regard. Gradual change does not necessarily imply a ‘move beyond’ a particular theoretical lens.

We systematically recap the main achievements and shortcomings of the field of semi-presidentialism in order to identify fruitful ways to advance research in the field. First, we map the general trends in semi-presidential studies with regard to theoretical foundations, major foci and methodological approaches. Secondly, we locate gaps in current research and provide recommendations for future studies. We ask:

1. What are the main research themes and basic theories in the field? Which definitions and case samples are used? How are these related, and how do the choices made frame our knowledge about semi-presidential systems?

2. To what extent does the evolution observed within the field regarding research themes and basic theories amount to a move beyond Linz’s ‘perils of presidentialism’?

3. Which relevant research themes are still underexplored, and what are the implications of current findings for future studies on semi-presidentialism?

REVIEW METHOD AND MATERIALS

For our structured review, we used an inductive method containing four main steps. In the first step, we traced the main semantic varieties of semi-presidentialismFootnote 15 in three major databases: the Web of Science, the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences and Google Scholar.Footnote 16 We also added books and articles from Elgie’s ‘The Semi-presidential One’ webpage and from the references listed in the three existing literature reviews.Footnote 17 The structure of summaries and tables of contents in books may not be as consistently organized as that of article abstracts, but we judged the contributions contained within books to be too valuable to disregard.Footnote 18 The initial search yielded a total of 690 English-language items (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of Selected Publications

In the second step, we excluded a number of duplicates, non-peer-reviewed publications, and items for which the full publication is not available in English. After reading article abstracts, summaries and the tables of contents of selected books, we ended up with a second sample of 327 peer-reviewed items, which either include semi-presidentialism as a term or that mention some institutional aspect of a particular semi-presidential country or countries.

In the third step, we identified each of the 327 studies’ main lines of research and trends of inquiry, in terms of research theme, definition, theory and case sample by reading abstracts, summaries and the tables of contents of selected books.Footnote 19 Following our inductive strategy, and based on our previous knowledge of the literature, we had a number of preliminary theme categories listed at the start of the coding process (for example, presidential powers, definitional debate, democratization and democratic survival, and intra-executive and executive–legislative relations). These categories were only slightly adjusted during the process as we added new themes, cases, etc. during the reading process. In terms of inter-coder reliability, the main coder frequently took a small sample out of the bulk of items and asked the second coder to validate the categorizations made during the process. Similarly, there was continuous discussion and elaboration between the two coders on the labeling and placement of categories along the way. The final list of categories is reported in Appendix Tables A1 and A2.

Due to the empirical character of the field, we classified research themes as being either part of the independent variable or part of the dependent variable. We labeled themes occurring in more than twenty publications as major topics, and themes found in ten or fewer as gaps. We then used the major themes to ascertain the main achievements of the field, and the gaps to identify areas for future study. The first part of our review thus involved taking a mapping approach. Our objective was to clarify the main achievements and trends in the research field, and to identify themes that were absent from it.Footnote 20

In the fourth and final step of the review, we closely read 20 per cent of the publications (sixty-five in all, listed in the Appendix) most cited in Google Scholar. To minimize selection bias related to the time of publication (older publications have had more time to be cited), we divided the 327 items into four groups, based on year of publication. We weighted the items to make sure that the number of times a given young publication was cited related properly to the number of times that other young publications were cited. In this way, we gave younger publications a fair chance of figuring among the final sixty-five items.

Our close reading primarily served as the basis for describing the findings and debates of each of the main themes identified in the full sample.Footnote 21 For each of the sixty-five studies in the subsample, we coded not just the main research themes but other occurring subthemes as well in order to ensure that the gaps identified in the first step of our review do in fact represent lacunae within the field.

Limits and Implications of the Method

Our choice of method and selection strategy has implications. We decided to review only English-language publications because of their predominance in the international research community, and because of our ambition to focus mainly on internationally recognized books, journals and top-cited publications. However, there is also relevant literature on semi-presidentialism in, for example, Chinese, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish. We cannot rule out the possibility that certain figures reported in this study regarding, for instance, covered regions and countries, or case and selection design, would be somewhat altered by the inclusion of non-English items.

While we weighted the items to avoid a serious bias in favor of older publications, the items in the second sample are nonetheless slightly older than those in the first one. The median year of publication is 2008 in the first, and 2005 in the second. Furthermore, as seen in Tables 2 and 3, the method of selection favors statistically oriented large-N studies and publications that cover more than one region.

Table 2 Regions Covered in Empirical Semi-presidential Studies

Table 3 Case Method of Semi-presidential Studies

THEORETICAL CORE OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIAL RESEARCH

Linz’s original claim – that presidentialism is perilous – has played a key role in shaping the field of semi-presidential studies.Footnote 22 Linz argues that presidential regimes suffer from inherently contradictory principles and assumptions.Footnote 23 Although noting the role of the military in the many occasions that a presidential democracy in Latin America has collapsed, Linz specifically targets the institutional content of presidential regimes as critical to explaining the region’s democratic difficulties.Footnote 24

LinzFootnote 25 fastens particularly on the role of the popularly elected president. First, he points out, presidential regimes use dual elections, for both the presidency and the legislature. These dual elections give voters direct influence over both parliament and the executive, but at the risk of setting their parliamentary and executive representatives at odds with each other due to the competing mandates they have received. Secondly, and in particular with reference to elections to the executive, the elected president is the only winner of the game. Losing presidential candidates receive no mandate equivalent to that enjoyed by the leader of the opposition in a parliamentary system. The result is a leadership style that tends to lack cooperative traits. Adding the president’s fixed term in office into the mix, moreover, we have a regime that faces the risk of permanent conflict. Because of their basic institutional features, therefore, presidential regimes are prone to conflict, even as crucial tools of conflict resolution are unavailable to them. These features lead to democratic difficulties for presidential regimes, Linz argues.Footnote 26

With its differentiation between presidential and parliamentary regimes and its focus on the effects of regime type on government and democratic performance, Linz’s contribution forms part of the empirical strand of New Institutionalism.Footnote 27 Linz was admittedly also engaged with the institutional origins of semi-presidential systems, elaborating in particular on the cases of France, the Weimar Republic and Portugal.Footnote 28 However, it is first and foremost his proposition for parliamentarism and against presidentialism that has strongly affected subsequent research on regime types: it has been frequently used as a programmatic framework for studying institutional effects. Partly as a consequence, the field tends to treat institutions as a given, without closely examining their origin or development. In a way, the influence of institutions is treated as ‘unidirectional; individual behavior is assumed to be largely determined by their participation in the institutions’.Footnote 29 Propositions about the assumed perils of presidentialism have had the virtue, then, of spurring debate and empirical research on the likely effects of semi-presidentialism, but with a rather unidimensional understanding of institutions.

Another approach that has been highly influential in the field is principal–agent theory.Footnote 30 Focusing on the studies in our second selection, particular patterns of delegation and accountability emerge in various regime types. These various chains of accountability, which connect citizens as voters (principals) to their elected representatives (agents), form the core of the principal–agent analysis for each regime type.

Comparing the institutional approach as inspired by Linz’s perils of presidentialism to that of the principal–agent tradition, the historical origins and normative assumptions embedded in different regime types are more clearly spelled out. While parliamentary regimes developed as ‘a historical accident of nineteenth century Britain’,Footnote 31 presidential regimes were consciously engineered.Footnote 32 Parliamentary regimes are therefore to be grasped as the outcome of historical evolution, whereas the presidential regime of, for example, the United States, reflects the aims and assumptions of the constitutional framers.

The US presidential regime was engineered with the particular aim of preserving liberty.Footnote 33 It was assumed that liberty could be preserved only if the institutions channel political ambition. Political ambition, in turn, could be channeled because of the rational and self-interested nature of actors: ‘elected officials will be influenced by the self-interested motive of re-election’.Footnote 34 The analytical focus of principal–agent studies of presidential systems is therefore set on the way institutional incentives affect rational and self-interested actors, which in turn affects the delegation and accountability of representative democracy.Footnote 35

Using this analytical perspective of how institutions frame actor incentives, parliamentary and presidential systems differ in terms of principal–agent relations. Under parliamentarism, executive authority and legislative authority are fused.Footnote 36 Under presidentialism, in accordance with the aims of the framers, ‘the diversity of interests […] gain representation and [are] pitted against one another’.Footnote 37 Presidentialism thus incorporates dual elections, thereby institutionalizing a ‘separation of origin’ between the legislature and the executive. It also excludes any executive power to dissolve the legislature or any parliamentary prerogative to terminate the government, thus institutionalizing the ‘separation of survival’.Footnote 38 Presidentialism, then, incorporates both the separation of origin and the separation of survival, and by consequence the separation of powers. Semi-presidential regimes, however, have dual elections and thus a separation of origin, but at the same time, they make the survival of the prime minister and the government dependent on the maintenance of parliamentary support.Footnote 39 As principal–agent studies have shown, the semi-presidential regime type is unique, because it ‘entails the possibility that both agents of the electorate – the president and the assembly – can exercise some, although often asymmetrical, authority over the government’.Footnote 40

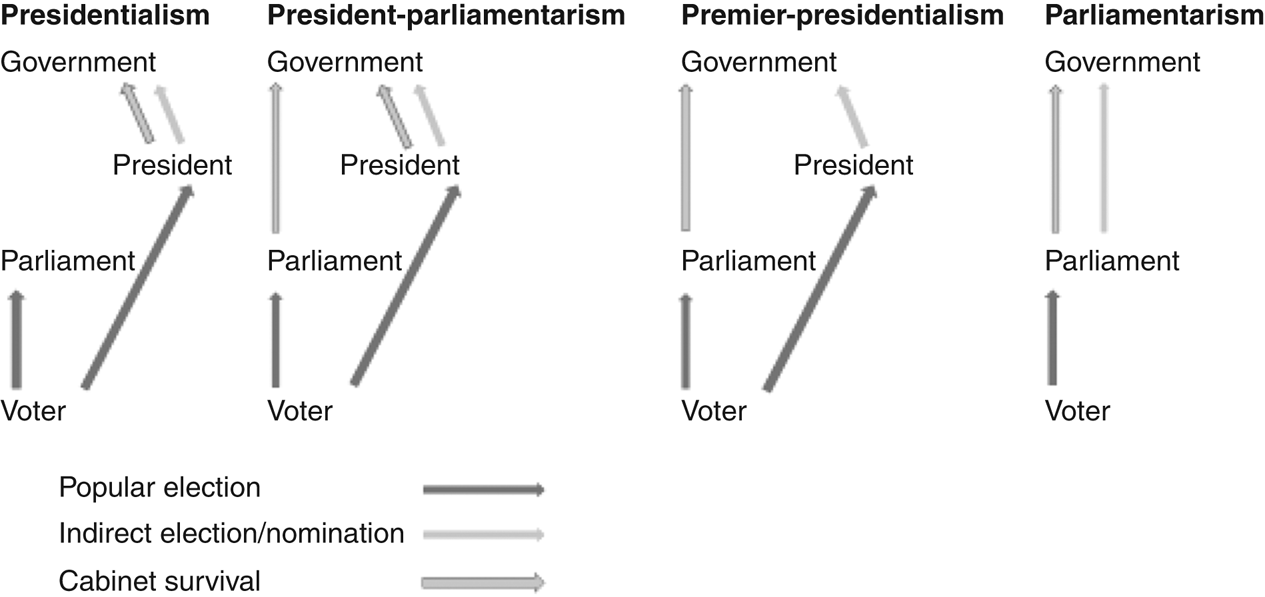

Although distinct from their presidential and parliamentary counterparts, semi-presidential regimes encompass vast differences. The ‘precise relationship of the president to the prime minister (and cabinet), and of the latter to the assembly vary widely’.Footnote 41 Within the principal–agent framework, semi-presidential regimes are accordingly divided into the two subtypes of premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism. In premier-presidential regimes, the prime minister and the cabinet are collectively responsible to the legislature. In president-parliamentary regimes, the prime minister and the cabinet are responsible to both the legislature and the president.Footnote 42 As illustrated in Figure 1, the analysis yields four unique regime types.

Fig. 1 Popular elections and cabinet survival under different regime types

The variations in regime type with regard to principal–agent relations are likely to affect the performance of the different regime types.Footnote 43 Under premier-presidentialism, the survival of the government is based only on parliamentary support; thus the parliament is expected to be more influential under this regime type.Footnote 44 Moreover, basing the survival of the government solely on parliamentary approval – and not on the president’s as well – implies a more stable basis for the government of the premier-presidential regime type.Footnote 45

To conclude, the principal–agent perspective provides a definition of semi-presidentialism that is distinct from the definitions of parliamentarism and presidentialism, and which distinguishes between premier-presidential and president-parliamentary regimes. As part of the analytical framework of rational choice institutionalism and contrasting with that of Linz’s empirical institutionalism, it ‘specif[ies] clearly the behavioral and causal assumptions that drove their theories’.Footnote 46 This analytical framework emphasizes the confidence relationship between the government and the assembly, and shows that the president and assembly parties decide the political composition of semi-presidential governments.Footnote 47 It further helps illuminate ‘cross-national variation and intertemporal shifts in partisan influence and external constraints’ and the way the same authority patterns produce deviating empirical results.Footnote 48 Although limited to the chains of authority between principals and agents, and without accounting for cultural or historical factors, the principal–agent approach has significantly contributed to the theoretical analysis and empirical findings of semi-presidential studies.

MAJOR TRENDS AND THEMES

Overall Research Trends and Themes

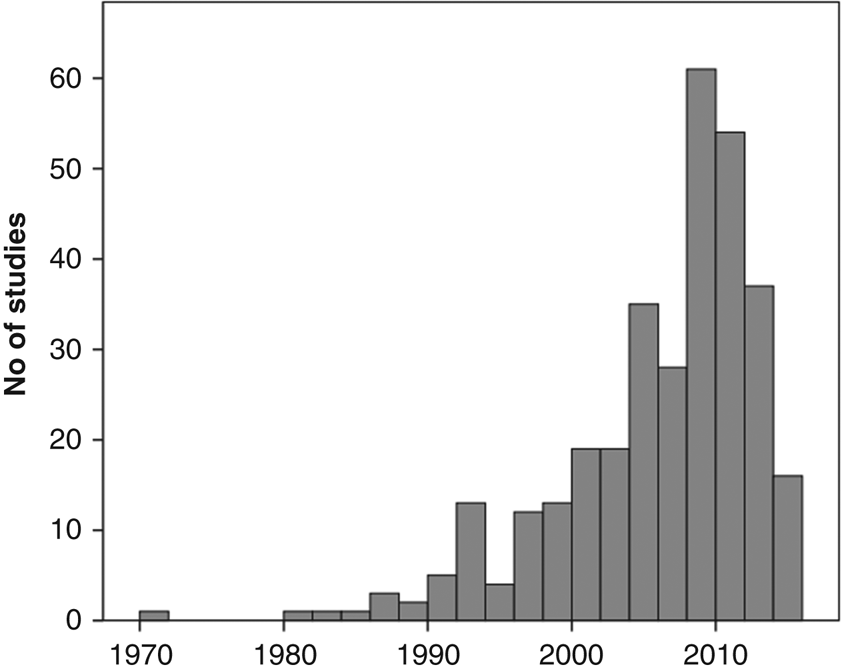

The number of publications on semi-presidentialism reached its peak around the year 2010 (Figure 2). The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the emergence of many new semi-presidential countries during the 1990s, marked the start of an increasing research focus on semi-presidential countries.

Fig. 2 Trends in semi-presidential studies 1970–2015 Note: n = 327 publication items.

Assessing the main research themes of semi-presidentialism (Table 4), we find, quite expectedly, that formal institutions and the regime type as such (presidential, parliamentary or semi-presidential) is clearly the most common – identified in 150 cases and predominantly as an independent variable. The category includes the adoption and diffusion of particular constitutions, that is, studies of how particular countries adopted their semi-presidential constitutionsFootnote 49 and how semi-presidentialism has diffused from one country to another,Footnote 50 as well as more particular issues such as the role of constitutional courts.Footnote 51

Table 4 Main Themes in Semi-presidential Research, 327 Items

a Includes all cases identified as dependent or independent themes in the 327 selection. One item may include two coded elements, which is why the total in the table adds up to 629.

b All identified categories are listed and separated into dependent and independent themes (see Appendix Tables A1 and A2).

More salient, however, and closely related to the second largest category in Table 4, formal regime type is assessed as an independent variable expected to correlate with political effects and outcomes, such as democratic performance, survival and accountability (111 studies). Table 4 furthermore reports that publications that address executive–legislative and intra-executive relations, including cohabitation and divided government, are quite common (fifty-one studies), followed by executive and presidential powers (thirty-seven studies), and political party factors (thirty-six studies) (we will review this literature in more detail below). We also identified twenty-two studies covering the debate over various definitions of semi-presidentialism (cf. Introduction). In addition, we report on a residual category of ‘other themes’ that were raised in only a few publications in each category. These themes are all listed in Tables A1 and A2 and some of them are addressed below as glaring gaps in the literature.

ElgieFootnote 52 describes the development of semi-presidential studies as consisting of three different but overlapping waves. The first wave centered on the definitional debate, the second on democratization, and the third on issues of ‘parties, power, and parliaments’.Footnote 53 As shown in Table 5 and Appendix Figure A1, our data support Elgie’s depiction of three different waves in the research field. This suggests that studies of political parties and presidentialization, as well as intra-executive and executive–legislative relations, come closest to what can be considered a current trend among semi-presidential studies.

Table 5 Trend of Research Themes, 327-selection

Regions and Case Approaches

Of the 327 publications, just twenty-nine focus on theory development and only five on methodological development, while 224 publications incorporate an empirical aim. This suggests that the field is first and foremost an empirical one.

Table 6 reports that post-communist countries account for 25 per cent of all the case samples in semi-presidential studies. The next most common are studies focusing on Western democracies, most of which examine European countries. Perhaps because our review covers only English-language publications, other world regions are sparsely represented. Even though Africa has nineteen semi-presidential regimes,Footnote 54 African cases are underrepresented (eight out of 327) within semi-presidential studies.

Table 6 Regions Covered in Semi-presidential Studies

Table 7 reports that single-case studies make up 38 per cent of all publications, followed by large-N and small-N studies. Single-case studies make up almost 60 per cent of all studies of the post-communist region.

Table 7 Number of Cases in Semi-presidential Studies

Although the number of large-N studies has increased since the 1990s, the apparent bias in favor of single-case studies and European and post-communist cases calls into question our ability to make tenable generalizations. To the extent that the literature on semi-presidentialism struggles with inconclusiveness about institutional effects and outcomes (see below), the smaller share of large-N studies is unsatisfactory. More sophisticated statistical methods and large-N designs would by no means guarantee that institutional effects are sufficiently dealt with, but the current imbalance in terms of research design is an apparent weakness of the semi-presidential literature.

Going beyond Linz?

To what extent has the field moved beyond Linz’s original propositions? The answer depends on how we interpret the question. The number of times Linz is cited, and his theoretical arguments are used, seems to be declining: 77 per cent of the publications from 1991–2009 include references to Linz, compared to 57 per cent of those from 2010 onward. Articles theoretically anchored in Linz’s arguments about the perils of presidentialism are correspondingly older (median year 2001) than those that rely on the main alternative, principal–agent theory (median year 2006).

It is a slightly different question, however, whether the field is actually moving towards ‘a rapid broadening of the research agenda beyond Linz’s concern with the adverse effects of presidents on democratic stability’.Footnote 55 We do see a tendency to move away from studies on defining semi-presidentialism or its effects on democratic survival. However, the trend towards studies focused on the president seems to have become even stronger. Since the effects of presidential elections and the style of leadership encouraged by presidential regimes were a major focus of Linz’s theoretical work, the influence of Linz seems to be changing its form rather than disappearing.Footnote 56 Studies still tend to focus on the variables that Linz highlighted as influential.

Democratization and Regime Survival

The empirical results in our second sample of publications suggest that some regime types are more conducive to democratic survival than others, although there is no clear-cut ranking of the four regime types.Footnote 57 In general, the results indicate that certain regime types are strongly correlated with democratic survival, that parliamentary democracies have a better survival record than presidential ones, and that premier-presidential democracies last longer than their president-parliamentary counterparts.Footnote 58 However, the extent to which the regime type as such is the cause of this pattern is debated, attached as it is to economic development as well as to the risk of military takeover associated with the presidential regime type.

The relative influence of regime type, economic level, military past and the way these variables are interrelated have been part of a persistent scholarly debate. Alfred Stepan and Cindy SkachFootnote 59 have argued that parliamentary democracies have a higher rate of survival than presidential regimes. José Antonio Cheibub,Footnote 60 however, empirically shows that presidential regimes are mostly found in countries where any type of democracy would be unstable, so that the shorter life expectancy of presidential regimes reflects a historical coincidence: namely, that presidential democracies are more often preceded by military regimes. Such cases, where democracy falls victim to external actors, are often associated with lower levels of economic development and a lack of economic growth.Footnote 61 Michael Bernhard, Timothy Nordstrom and Christopher ReenockFootnote 62 also find that economic performance has an even stronger effect on democratic durability than regime type.

Even if a country’s military past is considered a historical coincidence, however, democracies are not always ended by external actors, such as the military; they are sometimes ended by the elected incumbents, more often in presidential than in parliamentary regimes.Footnote 63 Milan Svolik elaborates on particular kinds of regime type effects, and finds that economic recession is related to lower levels of democracy and to democratic breakdown, while regime type, economic development and type of authoritarian past affect the probability of consolidating a new democracy.

So, do presidential regimes contain inherent risks? Or is it rather debilities inherited by previous military regimes, lack of economic progress or both? This remains a matter of disagreement, but it seems too early to rule out the possibility that presidential regimes are not institutionally flawed. Studies covered by our review indicate that certain regime types are more strongly associated with democratic survival than others.Footnote 64 Stepan and SkachFootnote 65 find parliamentary regimes to be ‘democratic overachievers’ compared to presidential ones. José Antonio Cheibub, Adam Przeworski and Sebastian Saiegh find similar indications. Although they argue that presidential regimes offer opportunities for coalition formation, they find that the average life expectancy of a presidential democracy is a mere twenty-four years, compared to seventy-four years for a parliamentary democracy.Footnote 66 Matthew Shugart and John Carey,Footnote 67 by contrast, compare the democratic records of different types of presidential regimes, distinguishing between presidentialism and the two semi-presidential subtypes. Elgie,Footnote 68 finally, finds that democratic survival is higher among premier-presidential regimes than among president-parliamentary ones.

While ‘the method of inquiry is fairly straightforward’ – ‘to determine the statistical correlation between particular regime types’ – it seems evident that using differing definitions and varying case selections makes it difficult to compare the results of different studies fully.Footnote 69 The findings of Stepan and SkachFootnote 70 rely on the consolidated democracies of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. Their end date, 1989, misses the many newer semi-presidential cases. Shugart and Carey’s list of democratic failures include West European cases, but not those from the post-communist region after 1991. Moreover, they exclude democracies with fewer than two consecutive elections, thereby minimizing the number of failures.Footnote 71 Cheibub,Footnote 72 with his later end date of 2004, includes the latter cases, but uses the term ‘mixed’ for semi-presidential regimes, which does not fit neatly with the subtypes identified by Shugart and Carey. Elgie’sFootnote 73 sample ends in 2008/2009, but focuses on the premier-presidential and president-parliamentary subtypes and does not compare their effects with those of parliamentary and presidential regimes.

Despite a degree of inconclusiveness in the literature relating to various samples and differing definitions, the effects of regime type on democratic survival appear to be contingent on the strength of both parliament and the president. Strong presidents correlate with worse records of democratic survival, as do weak parliaments and incoherent party systems.Footnote 74 Thus the combination of a strong president with a weak parliament and a fragmented party system seems particularly dangerous.Footnote 75 If we want to fully grasp the impact of semi-presidentialism on democratic prospects, then we should consider the larger institutional context – including the relative powers of the president and the character of the party system.Footnote 76

To conclude, semi-presidential studies have established a correlation between particular regime types and democratic survival. Parliamentary regimes fare better than presidential ones, and premier-presidential regimes are more successful than their president-parliamentary counterparts. Thus, and in accordance with Linz, scholars have stressed the influence of the larger institutional setting. Juan Linz and Arturo Valenzuela emphasized the risk of conflict, legislative stalemate and military takeovers. Yet presidential regimes have largely been able to form functional legislative coalitions; the risk of military coups seems more strongly associated with particular regions than with the regime type as such. Thus the factors accounting for the lower rates of regime survival in presidential and president-parliamentary regimes remain to be fully explored, but seem to differ from those initially suggested by Linz and Valenzuela.

Executive–Legislative and Intra-executive Relations

In accordance with Linz’s contention that presidential regimes are prone to conflict and semi-presidential regimes to politicking and intriguing, intra-executive and executive–legislative relations are among the most common dependent variables in the field.Footnote 77 The empirical results of these studies disclose deviations among the subtypes, and serve to reinforce and illustrate the findings in the previous theme on democratization and democratic survival.Footnote 78

In premier-presidential systems, the legislature enjoys exclusive power to dismiss the prime minister, making the cabinet dependent upon parliamentary support.Footnote 79 The political orientation of the government is thus likely to reflect that of the parliament – but not necessarily that of the president. On theoretical grounds, therefore, intra-executive conflicts are to be expected. The empirical studies by Oleh Protsyk confirm this expectation, and show that the likelihood of intra-executive conflict and the prospects for government formation reflect the extent of presidential powers, the party structure of the parliament and even the presidential ambitions of the prime minister.Footnote 80 Thomas Sedelius and Joakim Ekman,Footnote 81 moreover, find that high levels of intra-executive conflict are a significant predictor of pre-term cabinet resignations, suggesting that intra-executive conflict may increase cabinet instability.

Intra-executive conflict may result from ‘cohabitation’Footnote 82 – a situation ‘where the president and prime minister are from opposing parties and where the president’s party is not represented in cabinet’.Footnote 83 It has been argued that, since it makes intra-executive conflict more likely, cohabitation is a threat to the stability of democracy, often leading to irresolvable conflicts that induce the military to step in.Footnote 84 However, both Duverger and Sartori were optimistic about the introduction of semi-presidentialism; they referred explicitly to its ability to alternate between prime minister and president-led phases. In their view, cohabitation builds inherent flexibility into the semi-presidential structure.Footnote 85

The findings of our close reading suggest that premier-presidentialism is the subtype more likely to experience cohabitation, because the president has only informal means to influence the selection of the prime minister.Footnote 86 Under a president-parliamentary regime, however, the president has powers to both appoint and dismiss the government – which should enable him/her to avoid formation a government that opposes them.Footnote 87 In accordance with these expectations, periods of cohabitation are more common in premier-presidential regimes, and intra-executive conflict is more common during instances of cohabitation.Footnote 88 As expected, cohabitation can lead to severe tension and undermine general performance, especially when a democracy is young, or when there is no clear-cut constitutional provision setting out the distribution of power among the key actors.Footnote 89

In general, available records of semi-presidential countries from 1989 onward suggest that there is just one case of a semi-presidential democracy breaking down during a period of cohabitation (Niger).Footnote 90 The studies by Elgie, in particular, establish cohabitation as a situation that arises in circumstances where it can be managed within democratic bounds.Footnote 91 In particular, the premier-presidential form of government, where cohabitation is most common, seems to deny the president a position from which he/she can threaten the standing of an opposing cabinet. The distribution of powers within premier-presidential regimes also ensures that the executive governs through the legislature.Footnote 92

Even in premier-presidential regimes, cohabitation can largely be avoided by limiting presidential powers and introducing concurrent elections.Footnote 93 Elgie shows that concurrent elections and relatively low levels of presidential powers serve to decrease the likelihood of cohabitation. Still, Elgie cautions against the potentially destabilizing effects of cohabitation for new democracies, and Skach demonstrates the conflictual early experiences of cohabitation in the French Fifth Republic.Footnote 94

Adopting a multi-method approach, Sebastien Lazardeux examines the effect of cohabitation on policy outcomes under cohabitation in France. Lazardeux’s findings show that when the prime minister is optimistic about winning the presidency, and the legislative majority is similarly optimistic about winning the next parliamentary election, a wait-and-see strategy is preferred and the number of enacted laws tends to decrease. Conversely, when the prime minister is less likely to win the presidency and the legislative majority is unoptimistic about its future, the government is more eager to push for immediate reforms and the number of enacted laws increases.Footnote 95

By considering how empirical findings have illuminated the various regime subtypes, we conclude that the theoretical framework of principal–agent studies has contributed substantially to our knowledge of the workings and difficulties of semi-presidential regimes.Footnote 96 These studies demonstrate by ‘virtue of the confidence relationship between government and assembly, [that] all semi-presidential constitutions link parliament’s power over the government tightly to parliamentary elections’.Footnote 97 The framework thus incorporates parties and electoral systems directly into the semi-presidential analysis.

Presidential Powers and the Challenge of Measuring

As seen in connection to democratic survival, relations among the key actors often account for the proposed and observed effects of regime type, as do the executive powers of the president.Footnote 98 Executive powers are studied in different ways, from the development of a particular modelFootnote 99 to the way inherent executive powers are limited and shaped by a particular context.Footnote 100 Studies have been occupied by developing effective and valid measures of presidential power; some have even proposed that presidential powers, rather than semi-presidential subtypes, should be used as an independent variable when dealing with institutional effects on political outcomes.

A number of scholars has followed the early and oft-used method of measurement pioneered by Shugart and Carey.Footnote 101 Some researchers employ varieties of Shugart and Carey’s method,Footnote 102 whereas others have developed their own.Footnote 103 Scholars have furthermore shown a general tendency to assume that different ways of measuring presidential powers are equally indicative.Footnote 104 When tested, however, the indicators not only vary in strength; they also move in different directions, and do not form a ‘common latent construct’.Footnote 105 Doyle and ElgieFootnote 106 argue, however, that most social concepts ‘suffer from equivalent problems of construct validity’; they focus instead on improving the reliability of the indicators in question by increasing the number of countries reviewed, extending the time period covered and focusing exclusively on the constitutional aspects of presidential powers. ElgieFootnote 107 somewhat questions the empirical value of the semi-presidential regime type, preferring instead to study the influence of variations in presidential powers. This choice echoes the criticism of Siaroff, according to whom ‘there is really no such thing as a semi-presidential system when viewed through the prism of presidential powers’.Footnote 108 Cheibub, Elkins and GinsburgFootnote 109 add that constitutional provisions setting out executive and legislature powers more closely reflect the time and place in which the constitution was drafted than the particular regime type which is operating. They therefore recommend using ‘more precise categorizations based on particular attributes of legislative-executive relations that are believed to contribute to the outcome of interest’.Footnote 110

However, results of this kind do not negate findings that the subtypes of semi-presidentialism after cohabitation, presidentialization and democratic survival. Presidential powers form a considerable part of such influences, but the electoral system and the parliamentary party structure do as well. All three of these are variables whose influence is incorporated within the uniting framework of principal–agent analysis. Thus we agree with Schleiter and Morgan-JonesFootnote 111 that the framework of principal–agent theory has added value for semi-presidential studies, and that it could have even more. An exclusive focus on presidential powers, however, risks neglecting the larger institutional setting, as well as the way in which the subtypes of semi-presidentialism incorporate key dimensions of presidential power – in particular those related to cabinet survival. We would argue that, rather than abandoning valuable theoretical frameworks and findings, we would do far better to combine subtypes of semi-presidentialism with measures of presidential powers.

Presidentialization, Political Parties and Elections

While several studies focus on the institutionally founded powers of the president, others have sought to combine such formal aspects with the less formal ones. Linz argued that presidentialism stands out in that it combines a president with strong claims on legitimacy with a fixed term in office, and that these two traits combine into a regime type prone to conflict and legislative impasse. Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh,Footnote 112 however, illuminate the abilities of presidential regimes to form legislative coalitions and pass legislation. They argue that if presidential regimes are more brittle than parliamentary regimes (which they are), it is not because of such inabilities. Chaisty, Cheeseman and PowerFootnote 113 further show that presidents use different combinations of tools to overcome the difficulties of the separation of powers. Again, the findings of our close reading question the empirical support for some of Linz’s theoretical propositions, without altering the relevance of his general expectations.

Originating in the influence and independence of the presidency, studies of presidentialization assess the consequences of presidential powers.Footnote 114 While parties in parliamentary regimes organize to win legislative seats, parties in presidential and semi-presidential regimes organize to capture the executive branch.Footnote 115 Parties under the latter systems have less ability to control the executive, even if he or she hails from their ranks. Consequently, the executive in a presidential system has little to fear from his/her party colleagues.Footnote 116 As such, some scholars view presidentialization as serving to undermine democratic performance by making parties deaf to citizens’ demands.Footnote 117

It is a matter of debate whether presidentialization is ‘constrained by the formal configuration of political institutions’, or whether instead it represents a long-term trend in all types of regimes.Footnote 118 The debate here relates to the two concepts of presidentialization and personalization. Samuels and ShugartFootnote 119 contend that personalization – whereby a candidate with a strong personality and reputation rises to prominence – can be found in every regime type, whereas presidentialization is anchored in the dual elections and separation of origin and survival (of the executive and the legislature) which characterize presidential regimes.

A constitutional move from parliamentarism to semi-presidentialism would appear to be enough to spur presidentialization and, in particular, affect party strategies in the direction of winning the presidency.Footnote 120 However, both the theoretical expectations and the empirical results are divided here, according to which subtype is in question. President-parliamentary regimes, where the president has greater powers, tend to produce stronger party incentives to focus on the race for the presidency than do premier-presidential ones.Footnote 121 Yet among premier-presidential regimes, presidentialization is mainly observed in connection with certain informal factors: for example, instances in which the president and his or her party share an ideological orientation, and/or where the president acts as the head of the party.Footnote 122

Similarly, party research has shown that presidential power and electoral rules largely determine when parties decide to enter presidential elections on their own or form alliances. Jae-Jae Spoon and Karleen J. WestFootnote 123 show that medium-level presidential powers decrease incentives for party candidates to run on their own, and similarly that presidential term limits have a reducing effect on the number of presidential candidates. However, the extent to which direct presidential elections influence the empirical outcome is still debated.Footnote 124 Moreover, the way in which dual elections affect the party system depends on, among other things, the number of presidential candidates, the power of the president and whether the elections in question are held concurrently.Footnote 125 Predominantly based on single-country cases such as France,Footnote 126 IrelandFootnote 127 and Portugal,Footnote 128 studies have also addressed how dual elections affect voter strategies, and to what extent voters consider the presidential race as the first-order election. Results from these studies are somewhat inconclusive but indicate, quite expectedly, that where the president yields stronger powers, such as in France and Portugal, presidential elections are considered more important than parliamentary elections. Robert Elgie and Christine Fauvelle-Aymar,Footnote 129 for instance, find that stronger presidential powers are associated with significantly higher turnout in presidential than in parliamentary elections.

The power division between political parties and the president is also relevant in regards to control over cabinet posts and minister portfolios. Schleiter and Morgan-Jones find that in European premier-presidential regimes, parties have significantly less control over government portfolios than in parliamentary regimes. This effect is even stronger among top cabinet posts, such as prime minister, finance, foreign and interior ministers.Footnote 130

In the literature on semi-presidentialism, studies of parties, voting behavior and presidentialization show, accordingly, that party factors are related to regime type, and that they interfere with regime type effects. Empirical research thus indicates support for propositions about the institutional effects of semi-presidentialism on party and voting behavior, and that variation within the semi-presidential category (presidential powers, election rules and subtypes) matters in this regard.Footnote 131 We should emphasize again, though, that even in this part of the literature inconclusiveness on causal mechanisms persists and that there is a general over-representation of single-case studies.

RESEARCH GAPS

Our review of the main research themes shows that, although the field of semi-presidential studies appears to depart from Linz’s theoretical framework, and from focusing on democratic survival and the effects of regime type, it has continued his emphasis on effects relating to dual elections and the powers of the president. Identifying major research gaps as reported in Table 8 – that is, themes taken up in ten or fewer studies – further illuminates the influence of Linz. Within our first sample, few studies focus on the elite actor level, or on the mass level, or on the contextual effects of the historical or cultural setting. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of studies focus on national-level politics. Studies addressing public administration and bureaucracy, or even the prime minister, are rare as well – notwithstanding the adherence of researchers in the field to the norms and theoretical framework of empirical and rational-choice institutionalism.

Table 8 Identified Gaps of Semi-presidential Studies (327 Items)

Note: includes all cases identified as dependent or independent themes in the 327 selection. One item may include two coded elements, which is why the total number of observations adds up to 629.

As seen in all major themes in the field, many studies address issues surrounding the role of the president. It is quite surprising, however, that so few studies explicitly address the position or powers of the prime minister. In our screening, we found only three out of 629 observations in which the main focus was on the role of the prime minister. Although powers such as those over appointments and foreign policy are often shared between the prime minister and the president, and although the ambitions of the prime minister are known to affect the level of intra-executive conflict, scholars seem to be confining themselves to the original choice of focus.Footnote 132 While both Linz and Duverger did mention the prime minister, neither treated this key government actor as the main focus of their empirical agenda.Footnote 133 Moreover, the tendency to treat the role of the prime minister as a second-order issue seems to have persisted. We even seem at present to lack a proper structure to describe the various traits and powers separating one prime minister from another. This undermines our ability to make proper comparisons of changes in the real use of such powers, such as under cohabitation and non-cohabitation. Since he/she forms part of the executive – and thus constitutes a crucial link in the chain of democratic representation and accountability – the prime minister might be expected to draw frequent attention within the framework of principal–agent studies.Footnote 134

Another gap concerns studies of the bureaucracy and executive administration: only two of our identified studies focus on this either fully or partially. The bureaucracy forms part of the government’s resources and competences as well as its democratic chain of delegation and accountability.Footnote 135 Schleiter and Morgan-Jones,Footnote 136 who stress the theoretical opportunities provided by the principal–agent framework, support the call for more and deeper studies of bureaucracy. Furthermore, the authority exercised by the administration of the executive and legislative branches forms part of the core powers of these key state organs. Again, such studies could be managed within the existing principal–agent framework of analysis.

Analytical frameworks point to certain research issues, but exclude others.Footnote 137 We should therefore ask ourselves what risk we run – in terms of losing sight of various important issues – by remaining within Linz’s analytical framework, and indeed within the framework of principal–agent theory. As discussed above, empirical institutionalism ascribes little importance to variations in institutional context, institutional change or the way institutions relate to individuals.Footnote 138 It instead concentrates on a few basic institutional features. The principal–agent perspective, for its part, forms part of rational-choice institutionalism, an analytical framework that features more specific assumptions and normative aims, thereby anchoring its chosen focus on institutional features like the separation of powers as they affect the chains of democratic representation and accountability in different types of regimes. Studies of the different subtypes of semi-presidentialism have shown such approaches to be empirically valuable for measuring presidential power, as well as theoretically fruitful, due to the coherent framework – which incorporates the broader institutional setting – that they have furnished.

The influence of historical, contextual and individual factors is only mentioned in a few semi-presidential studies. Of the sixty-five publications chosen in the second sample of our review, eleven include historical aspects, but eight of these eleven treat historical aspects as a minor part of the analysis. Political culture figures as part of the picture in twenty-five of the sixty-five chosen studies, and so cannot be considered a neglected factor. However, twenty-one of these twenty-five publications include political culture as only one of several factors.

Although the semi-presidential literature has predominantly repeated Linz’s general proposition that presidentialism and semi-presidentialism are infested with institutional flaws, Linz’s writings also include contextual analyses of a number of regimes in Europe and Latin America.Footnote 139 In fact, DuvergerFootnote 140 acknowledged in 1980 that we cannot use semi-presidential constitutions by themselves to explain variations in practice without accounting for contextual factors. When, for example, explaining conflictual actions taken by presidents in a premier-presidential regime, or when analyzing particular tools used by presidents to overcome the separation of powers, formal presidential powers can only account for part of the outcome.Footnote 141 Constitutional provisions regarding executive and legislative powers are only intelligible in the context of when and where they were drafted, and democratic performance clearly reflects the larger socio-political context.Footnote 142

While the framework of empirical and rational-choice institutionalism portray the choice of institutions as mainly bound by rationally chosen motives,Footnote 143 Normative Institutionalism portrays constitutional choice as also reflecting norms and notions of legitimacy held by the actors involved. Historical Institutionalism, moreover, has integrated ideas of both large-scale and gradual change, influencing the function and effects of institutions.Footnote 144

ElgieFootnote 145 has expressed concern that including informal aspects means that ‘the study of semi-presidentialism risks being crowded out of the research agenda’. However, employing a broader set of New Institutionalist approaches does not imply downgrading the importance of institutional influence. While historical–institutionalist analyses commonly address larger historical developments rather than micro-level incentives, studies within that field can help improve our understanding of how context influences actor preferences.Footnote 146 For example, Henry Hale’s study of the impact of patronalism on relationships between informal and formal institutions in Eurasia uses formal institutions (including semi-presidential constitutions categorized as ‘divided executives’ and ‘competing pyramid systems’) as key variables. His analyses incorporate path dependency and historical–contextual factors to explain the impact of continuity and change on political outcomes in the post-Soviet sphere. Hale’s study convincingly demonstrates some of the limited but substantial effects that constitutional structures have on determining regime dynamics, and how deep-rooted institutional contexts and political culture interplay with formal constitutional structures. He shows that even in highly patronalistic contexts, constitutions can have powerful effects not by being formally obeyed, but by influencing expectations regarding how informal politics is actually organized. In this way, formal institutions shape expectations regarding who will be the de facto chief patron/s even in contexts where formalities and rules are regularly violated.Footnote 147

By more systematically adding historical and normative institutional approaches to the analysis, we would encourage new types of studies that may also deal more convincingly with the persistent causal and endogeneity challenges that are currently troubling the semi-presidential literature. The case for such approaches is furthermore strengthened by the apparent lack of single-case studies of non-European countries. Thus current trends risk retaining a European bias, which would reduce the general applicability of our empirical findings and call our assumptions and theoretical models into question.

CONCLUSIONS

In this structured review of semi-presidential studies, we have called attention to extensive variations in the field in terms of definitions, case samples and research themes. These variations reflect, among other things, the sudden spread of semi-presidential regimes, the inconsistent use of regime type classifications and the resort to a wide variety of case samples. In addition, the variation in cases studied incorporates an apparent under-representation of non-European countries. That noted, we have also found much commonality, both in the general adherence to the New Institutionalism analytical framework (particularly to the two strains of empirical and rational choice institutionalism) and in the shared use of a theoretical framework stemming from a few seminal publications.

The common thematic orientation can be collapsed into five major issues forming the bulk of semi-presidential research: democratization and democratic survival, presidential and executive powers, the debate over definitions, intra-executive as well as executive–legislative relations, and party and election system factors pertaining to the assumed and observed effects of direct presidential elections. The trend in the field seems to be gradually moving away from studies that debate definitions of semi-presidentialism, and away from studies focused on the direct effects of regime type on democratic survival. The trend is instead towards studies that address party system factors including presidentialization and the effects of presidential powers. This thematic development suggests that, although the use of Linz’s theoretical foundation is declining, the theoretical and empirical focus on the president is persistent – indeed, it is even stronger now than it was in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Anchored in the assumptions of neo-Madisonian theory, the principal–agent approach has revealed the normative intentions built into presidential and semi-presidential regimes. For example, the fact that the role of the president, in the eyes of those who drafted the constitution, was to circumscribe – in the interests of preserving liberty – the powers and ambitions of the self-centered actors involved. Accordingly, studying incentives, intentions and the separation of powers, scholars employing this approach divided semi-presidentialism into the two subtypes of premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism. Within the dominant research themes, these subtypes of semi-presidentialism have been of considerable theoretical and empirical value. Furthermore, the framework of principal–agent analysis has given rise to a fruitful combination, whereby an examination of the effects of regime type is joined to an analysis of the larger institutional setting (including the powers of the president and the structure of the party system), thereby yielding a coherent theoretical framework.

Principal–agent theory is also well suited to examining some of the gaps we have identified in the field, including studies of bureaucracy and legislative and executive administration, as well as the role of the prime minister in semi-presidential regimes. In this regard, semi-presidential research can benefit from previous research on parliamentarism, which has addressed the democratic chain of delegation and accountability in relation to the prime minister’s office and the bureaucracy.Footnote 148

In addition, the gaps we have identified show that studies of institutional effects are rarely related to their international, historical or cultural context. A contextual influence on the effects of regime type was assumed in the seminal contributions of Duverger, but scholars in the field generally seem to have preferred the established frameworks of either empirical institutionalism, based on Linz’s proposition for parliamentarism over presidentialism, or rational choice institutionalism.Footnote 149 These frameworks are not suitable, however, for advancing our understanding of institutional maturation and contextual adaption, or of how actors are both influenced by (and in turn influence) institutional frameworks. These studies tend to take the start of a new constitution as their natural point of departure in a way that fails to incorporate the way context and pre-constitutional settings impose restrictions on constitutional adaption and influence. We contend that incorporating the analytical frameworks of normative institutional approaches may improve our understanding of the way institutions develop, change and mature after the process of establishing a new constitution. Similarly, Historical Institutionalism may, to the benefit of research on semi-presidential regimes, improve our understanding of how previous institutions and context impose restrictions on constitutional choices.

Research on semi-presidentialism, like research on institutional effects more generally, struggles with endogeneity. Our review has established a predominance of single-country approaches in the field and a general inconclusiveness about institutional effects and outcomes. Without claiming that statistical methods and more large-N designs would guarantee that institutional effects are sufficiently addressed, we recognize the need for more methodologically sophisticated and empirically sound large-N studies. The bias towards single-case studies of European and post-communist countries, and the corresponding lack of single-case studies of African countries in particular, further underline the need for additional semi-presidential studies. Failing to go beyond the analysis of European semi-presidentialism risks undermining the general applicability of the findings and theoretical models in this field of research.