If it is indeed true, as one reads here and there, that steam was first used on a large scale by the English, the French, and the North Americans with steam engines, steamers, steam jets, steam guns, and so on: then some German has the merit of first having tested the benefits of steam by preparing noodles with [it], thus becoming the inventor of the celebrated steam noodles.Footnote 1

Published in the Munich weekly Fliegende Blätter in 1845, this satire by Hermann Marggraff (1809–1864) pinpointed a German predicament of apparently growing concern among the German bourgeoisie: that the Germans were falling behind. More specifically, it was the German, or der Deutsche in the masculine singular, who was not keeping up with his peers. As they were developing steam-powered machinery, all he could come up with was Bavarian dumplings.

This article argues that just as a German national movement was acquiring unprecedented political potency in the 1840s, a highly gendered sense of German national ineptness was widespread among the German bourgeoisie. In the context of European industrialization, this collective insecurity was informed by essentialist notions of German national character and exacerbated by shifting and contradictory gender ideals. Disparaging representations of the stereotypical German man oscillated in humorous texts and illustrations of the 1840s between the emasculated philistine and the hypermasculine quixotic hero. The German was either sleepy or headlong, comfort-loving or bellicose, resigned or relentless. Tracing this duality, the following article suggests that both versions of the German man articulated his inadequacy in the face of a corruptive, feminized modernity. This finding relativizes the scholarly emphasis on liberal voices whose disparagement of German character is largely understood as a form of political criticism.Footnote 2 Shifting the focus of the analysis from dissenting political satire to representations in politically ambiguous, humorous bourgeois publications calls attention to the prevalence, complexity, and heavy gendering of self-disparaging images of the German man. By doing so, this article seeks to expose how gender and national stereotypes in nineteenth-century Germany were mutually destabilizing and repeatedly negotiated, profoundly shaping contemporaries’ understanding of the world changing around them.

Gender and National Character in the German 1840s

It is well-established in the literature that gendered constructions intersected with and informed national stereotypes in the nineteenth century as part of a broader shift toward essentialized social categories. In the face of bewildering change, people clung to perceived national and gender characteristics as natural constants assumed to be primordial, involuntary, and the cause rather than the result of historical developments.Footnote 3 As the “foundation of nation and society,” ideals of masculinity were central to the consolidation of a national ethos and identity.Footnote 4 German masculine virtues were frequently construed as counterimages to the French. Especially in the context of the Napoleonic wars, German valor, loyalty, and morality were contrasted with French inconstancy and frivolity.Footnote 5

At the same time, gender ideals were themselves changing. The most pivotal development prompting a shift in gender roles in the nineteenth century was the rift between the public and the private spheres.Footnote 6 The emergence of centralized state apparatuses and corresponding economies, coupled with the beginnings of industrialization, fostered a new, rigid division of labor between men and women that rested on the heterosexual union as the basic unit of bourgeois society. Husbands were expected to perform professionally within a fast-changing economic and political public sphere, while their wives were entrusted with the preservation of tradition in the private, domestic realm.Footnote 7 Reinforcing this division of labor were essentializing notions of male and female traits. The ideal woman was also the most authentically feminine woman–domestic, chaste, and emotionally intuitive by her very nature—the perfect complement to the innately rational and industrious man.Footnote 8 While the ideal of domestic femininity did not steer far from earlier constructs, masculine ideals of chivalry and valor were being challenged by the requisites for middle-class respectability, namely rationality, sensitivity, restraint, and professionalism.Footnote 9

These changes were felt throughout western and central Europe. Arguably, they only rendered national discrepancies more glaring. In the 1840s, the German economy was significantly poorer and less industrialized than its French and British counterparts.Footnote 10 Although Berlin was growing fast, it was still not a vast metropolis the likes of Paris or London,Footnote 11 and the import of British technology was only just introducing the railway and other industries to the German territories.Footnote 12 There had been no German revolution, and there was no centralized German state. Marked by the spread of pauperism, social unrest, and the rise of both liberal and conservative political movements, the early 1840s were a time of both crisis and promise, not least among educated German men, many of whom cultivated hopes for national unification.Footnote 13 Exacerbating this volatile political and social climate was the context of religious fragmentation, where the intersection between shifting gender roles and concerns surrounding modernization was perhaps most visible. Marriage laws, celibacy, and the overarching issue of (mostly middle-class) men's sexual rights were a major point of contention that drove ideological and confessional polarization in the German territories in the 1840s.Footnote 14

Against this backdrop, many German intellectuals cultivated a German national identity that was based on a perceived linguistic and cultural cohesion spearheaded by German poets and philosophers (Dichter und Denker).Footnote 15 Throughout the nineteenth century, the ever-evolving national ethos of German spiritual unity was intimately entangled with stereotypes of German character as profound, introspective, thorough, and naive.Footnote 16 The gendering of these national stereotypes was neither consistent nor coherent. Gendered requirements and expectations produced prescriptive ideals of the modern man and woman alongside descriptive, often disparaging representations of male and female “types.” These intersected with national stereotypes in varied and revealing ways, producing a rich gallery of images that included self-disparaging representations of the German man. As I will argue, thick, layered depictions of German character did not just affirm narratives of national singularity or provide compelling rhetoric for political criticism. They also resonated deeply with widespread frustrations and anxieties surrounding contradictory gender roles, the demands of modernity, and the ability of the German man to comply.

Sources and Methodology—Gender, Nation, and Class in Disparaging Humor

The following analysis focuses on disparagingly humorous representations of the German man. These are taken primarily from the illustrated Munich-based periodical Fliegende Blätter (FB), mostly during its first year of publication, 1845. The analysis will also trace intertextualities with other German writings from roughly the same period, chief among them Karl Julius Weber's (1767–1832) bestselling Dymokritos (1832–1840) and a humorous piece on modernity, gender, and national character by the satirist Moritz Gottlieb Saphir (1795–1858).

The emphasis specifically on the FB serves several purposes. First, the FB was the harbinger of a new type of humorous content that garnered popular appeal among the German educated classes irrespective of regional and confessional differences. Striving to cater to as broad an audience as possible, the FB crafted lighthearted, nonpartisan satire suitable for mass consumption, to be enjoyed by the whole bourgeois family.Footnote 17 The journal's elaborate illustrations were a novelty in terms of quantity and scale of distribution. From the start, its circulation of several thousand exceeded that of most political or theological journals, reaching an estimated 20,000 subscriptions by the 1870s. Each subscription likely reached dozens of readers in clubs, cafes, shops, and libraries. By the end of the century, the FB achieved resounding success throughout the German-speaking world and was also distributed in the United States and several North European countries.Footnote 18

Second, the journal's location in Munich—the Catholic-majority capital of Bavaria—provides an opportunity to examine German identity discourse from perspectives that are often neglected. Existing scholarship has stressed the predominantly Protestant, expressly anti-Catholic orientation of German nation-building, placing tropes of German national character mostly within this ideological context.Footnote 19 Focusing on a Munich-based journal that was at the same time a trendsetter across the German territories can significantly broaden this historical perspective. Bavaria was a bastion of regional identity and independence that posed a considerable challenge to both Prussian and Austrian dominance—which represented the two possible trajectories for national unification in the 1840s.Footnote 20 At the same time, Bavaria was home to the Walhalla, one of the earliest and most ambitious projects of pan-German nationalism, inaugurated in 1842.Footnote 21 As the capital of one of the oldest German constitutional monarchies, Munich was both a center of conservative Catholicism and a stronghold of liberalism at a time when German party-politics was just emerging.Footnote 22 The FB was firmly embedded in the city's social fabric, where it established its initial subscription base. Founder and illustrations editor Kaspar Braun (1807–1877) was a graduate of the city's celebrated Academy for Fine Arts, and many of the journal's illustrators were members of the Munich artists’ society.Footnote 23 Analyzing disparaging humorous representations of the German man in the FB while considering their extensive intertextuality with popular works produced and distributed elsewhere in the German territories can thus capture otherwise overlooked complexities and commonalities during a politically tumultuous time, in which a distinct yet fragmented German bourgeoisie was shaping its national identity.

The choice to focus on humorous sources is rooted in more theoretical considerations. During the period in question, humorous content in general had the dual advantage of largely avoiding censorship constraints in the German territories and appealing to a much wider consumer base than most journalistic content.Footnote 24 Yet beyond this technical advantage, collectively self-disparaging humor is a particularly illuminating and confounding type of historical source. The positive reception of disparaging humor is generally considered as contingent on its enhancement of the subject's sense of superiority.Footnote 25 It is therefore difficult to reconcile the savage ridicule of the typical German man in the sources reviewed here with their immense popularity among the very group most identified with the disparaged figure—contemporary middle-class German men.

In their review of theoretical literature on disparagement humor, Mark E. Ferguson and Thomas E. Ford cover various possible explanations for this phenomenon. One of these, based on social identity theory, hinges on the distinction between social and personal identity. In an in-group setting, personal identity takes the lead, whereas social identity assumes greater relevance in intergroup settings. A sense of superiority based on personal rather than social identity may thus arise from the disparagement of one's own group.Footnote 26 Recent research notes that satire at its structural core is less about identifying objects worthy of criticism than insisting on the otherness of an object with which the satirist shares an uncomfortable degree of identification.Footnote 27 It is therefore likely that unflattering representations of the German man often produced a sense of superiority among individual readers and viewers, especially in light of the elaborate, reference-heavy style typical of these genres.Footnote 28 By virtue of being in on the joke, those incisive, self-aware Germans who recognized every allusion and topos could, theoretically, feel themselves far superior to their unwitting peers.

Although a sense of superiority within the German bourgeoisie was likely an important factor for the popularity of such content among the educated classes, it does not explain the preoccupation with specifically German character and its manliness or lack thereof. Ridicule of bourgeois types would have sufficed, and indeed, there was plenty of it.Footnote 29 Yet the sources selected for the present analysis made it a point to ridicule the German bourgeois man, identifying his Germanness as the main cause for his ill-adapted masculinity. At a time when German national identity was the object of intense deliberation, and amid considerable confusion surrounding gender roles and specifically masculine ideals, it seems that disparaging humor also served as an effective vehicle to thematize and reconcile the many contradictions that plagued these subject matters. Humor's ability to bridge incompatible, contested elements makes it an effective tool for exploring and redefining the peripheries of identities in flux or in the making.Footnote 30 Finally, humor by its very nature is ambiguous in its meanings, often masquerading between disparagement and admiration, ridicule and fascination almost indistinguishably.Footnote 31

During the period in question, humor's capacity to accommodate contradictions seems to have been especially well-suited for the topic of masculinity. As the primary actors within a new social, political, and economic order, modern men faced unprecedented and conflicting expectations that generated competing masculine ideals.Footnote 32 In her study on representations of masculinity after the French Revolution, Abigail Solomon-Godeau notes the alternation in French Neoclassicism between “overemphatic virility” and “exaggerated effeminacy or androgyny,” placing it within the context of “the transition from earlier courtly models of masculinity to recognizably modern, bourgeois ones.”Footnote 33 Solomon-Godeau explains the prominence of “feminized masculinity” in this period as a sublimation of otherwise illegitimate desire, as femininity gradually became the sole “domain of specularity, exhibitionism and display.”Footnote 34

This shift toward more binary gender constructs created new discrepancies, not least because the association of femininity with specularity and display was entirely at odds with the chaste, domestic femininity on which the new division of labor was predicated.Footnote 35 Rita Felski's study on The Gender of Modernity explicates this disparity by calling attention to another important distinction introduced by industrialization—that between production and consumption. The industrialized market economy reinforced bourgeois gender roles, casting men as professionalized producers and women as irrational, insatiable consumers. At the same time, the role of consumer undermined women's confinement to private domesticity, placing them firmly within the marketplace as both desired objects and desiring subjects.Footnote 36 Far from representing tradition, consumerism was as much the face of modernity as industrial production, perhaps more so.

The emblem of feminine consumerism was fashion. An immediately recognizable, visual indication of someone's up-to-dateness, fashion became a powerful symbol for the arbitrary changeability of modernity. To be fashionable was to be frivolously feminine, but it was also a status symbol that attested to one's wealth and social sophistication. In its perceived role as an inauthentic facade that perpetuated female erotic desire and amplified female desirability, fashion was seen to undermine the relationship between the sexes and spur rampant adulterous behavior.Footnote 37 In short, consumerism and its fashion dictates represented a parallel, feminized modernity that was destabilizing and corrupting.Footnote 38 In the German context, “fashionable” was often synonymous with “French.” European fashion was indeed French dominated, with Germans, among many others, adopting French styles.Footnote 39 Fashion was featured center stage in gendered national comparisons between the French and the Germans. The dutiful, devoted German mother and wife was contrasted with the elegant, adulterous, and fashion-obsessed Frenchwoman. German women who were preoccupied with fashion and social elegance were condemned as Frenchified.Footnote 40

The association among consumerism, modernity, and femininity did not just undermine masculine ideals of rational agency and respectability. It also inevitably complicated the relationship between masculinity and consumerism and the role of the male consumer. A prime and early example of this was the British Macaroni craze in the 1770s. The Macaronis were overly fashionable young men who had returned from their continental Grand Tours with supposedly foreign, effeminate affectations. As shown by Amelia Rauser, exaggerated depictions of the Macaronis turned them into a simultaneous symbol of worldly sophistication, inauthentic pomp, and endearingly unapologetic eccentricity. As such, they both affirmed and challenged contemporary constructs of gender, nation, and class.Footnote 41 Jason G. Karlin demonstrates how similar conceptions of Western modernity transformed perceptions of gender and national identity in Meiji Japan. Received as a force of progress and civilization, Western fashions and tastes were also likened “to the effeminacy of fashion, consumption and materialism,” and as such a threat to the authenticity of Japanese culture and masculinity. Japanese men who emulated these Western norms were ridiculed, like the Macaronis, as effeminate and affected.Footnote 42

Throughout the nineteenth century in Europe, the fashionable male consumer as a type assumed many guises, from the dandy and incroyable to the Flaneur, controverting and complicating misogynist tropes that equated fashionableness with irrational female desire. Oft-ridiculed, oft-envied, this male type was both deplored and admired for being a seemingly undeserving winner of modernity, someone who enjoyed the benefits and freedoms of the market economy without fulfilling the manly duties of industrious production and married life.Footnote 43

As I have shown, the contestation and confusion surrounding the intersecting categories of nation, gender, and class, and particularly bourgeois masculinity as the foremost vessel of nationhood, found ample expression in satirical and caricatural content. The sizeable literature on this historical complexity draws primarily on examples from nineteenth-century France and England. Applying the concepts and insights developed by this scholarship to neighboring Germany, the following will analyze humorous, self-disparaging depictions of the German man's awkward attempts to navigate modernity between masculine production and feminine consumption in the 1840s.

Not Masculine Enough: The German Philistine

The philistine (Philister) made its debut as a widely used term in German student fraternities of the early nineteenth century, where it designated the unintellectual, lower-middle class residents of university towns.Footnote 44 This mocking characterization quickly established itself as a Romantic literary topos. Clemens Brentano (1778–1842) dedicated a monograph to the philistine in 1811, while E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822) fashioned him as a self-important, thoroughly domesticated tomcat in the 1819 novel The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr.Footnote 45 Although the term in English is generally associated with anti-intellectualism, the nineteenth-century German philistine was more a symbol of pseudo-intellectualism, characterized by misplaced enthusiasm and unrefined or unoriginal taste. Virtually interchangeable with the Spießbürger, this topos also indicated class inferiority from the point of view of a university-educated man, who was its main reproducer and audience. Especially during the period in question, but also much earlier, the philistine was typically depicted in a domestic setting, often wearing a nightcap, indicating his passivity and obliviousness to the political and social goings on of his time.Footnote 46

It did not take long for this male type to become associated with German national character. Following the 1830 July revolution in France, Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) referred to his disappointingly inactive German compatriots as “fat philistines.”Footnote 47 In his “Deutschland: ein Wintermärchen” from 1844, the French are lamented as “becoming philistines, just like us [the Germans].” Having lost their former sprightliness they now rhapsodized “about Kant, about Fichte and Hegel.”Footnote 48 One of the most prevalent personifications of the philistine, the provincial, nightcapped monoglot Vetter Michel, emerged in the 1830s and 1840s as the Deutsche Michel—the most recognizable visual personification of the German people to this day.Footnote 49 Though the Deutsche Michel is acknowledged as a central German auto-stereotype in the nineteenth century, his glaring emasculation has not garnered scholarly attention. A socially unsophisticated, professionally unsuccessful, unmarried, and perpetually domestic man, the German philistine demonstrably interacted with contemporary gender roles.

The philistine's emasculation is made explicit in a stand-alone illustration from the twentieth issue of the FB depicting a stern-looking, mustached gendarme offering a numbered uniform jacket to a bewildered man in a nightcap, house robe, and slippers. The illustration is titled “Väterliches Regiment” (see Figure 1) and is accompanied by a short dialogue between the gendarme-cum-patriarch and the man, who we learn is called Lorenz Kindlein. “Away with the dressing gown, with the police-averse [polizeiwidrigen],” says the gendarme; “it is effeminate [der verweichlicht]!” To which Kindlein abashedly replies, “I beg your pardon, but I shall catch a cold.”Footnote 50

Figure 1. “Väterliches Regiment.”

“Väterliches Regiment” appears to refer to another unattributed illustration from the previous issue of the FB, titled “Eisenbahnvermessung” (see Figure 2). This considerably more elaborate illustration features Kindlein in the same sleep-appropriate attire, this time faced with a party of construction workers barging in through the window and hammering a pole clean through his bed. This time the accompanying dialogue is between a discombobulated Kindlein at his desk and “the geometer,” at whom Kindlein is squinting above his glasses. “Sir, honored as I am by your visit,” he says, “I nevertheless must confess that it was my intention today, after finishing my usual number of verses, to sleep in my bed.” “Sleep where you like,” replies the geometer, “but take note of this official proclamation: in the name of the railroad!”Footnote 51

Figure 2. “Eisenbahnvermessung.”

Visually, both Kindleins are indistinguishable from the Deutsche Michel, who was by this time a recognizable personification of German national character. A Deutscher Michel with identical facial features appears in an earlier issue of the FB, alongside Robert Macaire, John Bull, and Brother Jonathan, the personifications of the French, the British, and the American peoples, respectively.Footnote 52 That the typical German in “Väterliches Regiment” and “Eisenbahnvermessung” is called Lorenz Kindlein, after the protagonist of August von Kotzebue's (1761–1819) play Der arme Poet (The Poor Poet) from 1813,Footnote 53 was a sophisticated deviation from an established trope.

Kotzebue's Kindlein had already been depicted in a nightcap and dressing gown at least once before in Carl Spitzweg's now famous painting Der arme Poet, exhibited in Munich a few years prior in 1839.Footnote 54 Interpreted through the years as both a romantic idolization of the poet and a biting satire, Der arme Poet has a tortuous reception history that reflects much of the ambiguity surrounding the philistine as a representation of German character.Footnote 55 A regular contributor to the FB, Spitzweg may have been involved in the production of the two Kindlein illustrations. Especially in “Eisenbahnvermessung,” the reference to Der arme Poet is conspicuous. Kindlein's striped robe, knitted brow, and glasses are almost identical, as are the piles of scribbled paper bound together with strings and the strewn battered books. Yet unlike Spitzweg's Kindlein, the Kindleins depicted in the FB are not just victims of their own poetic aspirations; they are subjected to the senseless, soulless machinery of the modern industrializing state. In the face of the gendarme and the geometer, both adequately professional men and representatives of the establishment, Kindlein fails to stand up for himself and is entirely ill equipped to comprehend the situation. Underscoring Kindlein's emasculation are his infantilization—indicated also by his name, a diminutive form of the German word for “child”—and his domesticity. His attire is fit for the bedroom, which he does not share with a spouse, and his vocation as a poet, ridiculed rather than romanticized, is of little use in an industrializing economy. The bust in Kindlein's own image in “Eisenbahnvermessung” makes clear that his domesticity is perennial. The celebration of his person for posterity too depicts him in a nightcap and with the same uncomprehending expression. The grotesque addition of a wreath serves as the only distinction between the Kindlein standing in his bedroom and his likeness.Footnote 56

Kindlein's domesticity indicates his failure to partake in modern industrial production. His attire and destitution, however, also point to his deficiency as a consumer. In this, he was the antithesis to the fashionable, carefree urban dandy, a type often satirized in the FB.Footnote 57 Though similarly unmarried and unemployed, Kindlein's excessive earnestness and diligence in writing the same number of verses every day provided a stark contrast to the dandy's promiscuity and aversion to duty. In his thorough dedication to an orderly, unchanging domestic routine, Kindlein was decidedly unfashionable. His exclusion from the cycle of mass production and consumption indicates his obsoleteness. As a stereotypical German, he represented the Germans’ backwardness on the European stage.

As noted by Warren Breckman, the relegation of the German poet or philosopher to the rank of philistine in the 1830s and 1840s was intricately connected with dissenting liberals’ concerns that the absence of a German political revolution was due to a flaw in national character, namely the Germans’ inherently private, contemplative nature.Footnote 58 The examples reviewed here place this frustration with German character in the context of a broader underlying insecurity. It was not just the Germans’ political apathy or aversion to change that were of concern, but an inaptitude to meet the changing times as men, the primary agents and beneficiaries of an industrializing economy.

National comparisons therefore underpinned more than disappointed liberal hopes for political reform. The ninth volume of Karl Julius Weber's twelve-volume Dymocritos undertakes a humorously systematic comparison of the nations of Europe. Dymocritos was written shortly before Weber's death in 1832 and published in installments between 1830 and 1839. In 1843, it came out in a second edition, becoming one of the bestselling German works in the nineteenth century.Footnote 59 The chapter on “the Germans” in volume 9 has sluggishness as its central theme, with the moto “haste makes waste” (Eile mit Weile) accompanying the title. It is featured fourth, following the French, the Italians, and the English, purportedly in order of importance: “Surely a German may humbly rank the Germans fourth among the four most civilized peoples of Europe?”Footnote 60 “Our ancestors,” wrote Weber, considered anything important twice, once drunk and once sober, but then they acted—and how? Like Germans, with the most meticulous, slowest, and greatest orderliness a nation ever had.”Footnote 61 This thoroughness and love of order, argued Weber, resulted in hindered historical development: “The oak, our ancestors’ favorite tree, takes centuries to cultivate, and so we too took long for our spiritual cultivation.”Footnote 62 Not only did it take centuries, but the Germans’ eventual cultivation was confined to cultural achievements that barely left a mark in the economic or political arenas.

Hermann Marggraff's piece, quoted at the opening of this article, similarly turned to national comparisons to indicate the Germans’ industrialization gap. While the French, the English, and the Americans boasted steam engines and heavy machinery, the German brought Bavarian steamed dumplings to the table. Aggravating the German's deficiency was his lack of social sophistication and awareness. In a fashionable banquet, Marggraff suggested, an overly keen German could raise a toast to “one of the most important inventions to grace humanity, at the same time a truly national invention, ...-steam noodles [Dampfnudeln].”Footnote 63

Of all the rivals outshining Marggraff's German, it was the Frenchman who emerges as his true nemesis. The main object of Marggraff's satire was the growing custom of fashionable banquets, described as an empty, self-important, feminine bourgeois activity. What was worse, everyone was always trying to please and impress some French guest at these events. The impertinent Frenchman would then smugly report back that “the works of Eugen Sue and George Sand were displayed for me on the ornamental tables of the ladies [Paradetischen der Damen]; one spoke to me about Rousseau and Voltaire instead of Goethe and Schiller.… this measure of the Germans’ courtesy would please us with the voluntary cession of the Rhine border.”Footnote 64 This was likely an allusion to the 1840 Rhine Crisis, during which France had reasserted territorial claims over the west bank of the Rhine.Footnote 65 In trying to mimic the superficial, feminine ways of the French, Marggraff argued, the Germans devalued their own culture in return for patronizing audacity and chauvinist aggression. The sense of a distinctly masculine humiliation is apparent. German ladies displayed the works of a French female novelist—George Sand (1804–1876)—on feminine tables. The fashionable German women in Marggraff's banquet unabashedly pander to the French male gaze. More than technological advancement, the Frenchman's singular advantage over the German was his ability to comprehend the dictates of fashion and the status-affirming function of modern consumerism.

The German's lack of sophistication and sense of fashion also found expression in his portrayal as unwittingly derivative—another characteristic feature of the philistine.Footnote 66 A mock book advertisement for the “original work” Robinson Crusoe in the FB painted the picture of a clueless German reading public led on by a publishing industry overtaken by foreign interests. “The German people is hereby made aware,” the advert solemnly declared, “of the following original work, published by the undersigned,” one “Michel Nachmacher [copycat].” Nachmacher turned to list the merits of the original work, “translated from English by a society of German scholars,” printed in Paris on “fine Dutch paper,” with illustrations engraved by the “best of England's artists.” Upon receiving the third and final installment, readers would receive the bonus gift of “an exquisite, large steel engraving of Napoleon and his generals as a lovely house ornament for every German family.” Those enthusiastic subscribers who ordered upward of six copies would receive an additional “portion of roast meat, half a bottle of wine, and material for a pair of summer trousers. Should women also partake in this transaction, they are guaranteed a new parasol…”Footnote 67

The German man is depicted here as so impressionable that he could be tricked into selling his identity for a mess of pottage. The baits used—an engraving of Napoleon, a morsel of food, and some fabric—indicate his impoverishment and naivete. While men could be tempted with a half-drunk bottle of wine and material with which to make their own trousers, it took a new, fashionable outdoors accessory to win over the women. The fashion-savvy German woman is not indicated as the German man's spouse but as an independent consumer, and one that is harder to manipulate at that.

Here, as in Marggraff's banquet, German domesticity and backwardness are also linked to a homely preoccupation with food. As noted by Weber in Dymocritos, “German nationality has until now been based merely on sauerkraut, sausage, and buttered bread [Butterbemme].”Footnote 68 In his “humorist lecture” given in 1844 in the Austrian spa town of Baden, Moritz Gottlieb Saphir similarly used food to indicate the German's retirement to simple domestic comforts. Saphir was a well-known satirist who rose to fame in Berlin and had been based in Munich between 1829 and 1833. In the 1840s, he was editor of the popular Viennese daily Der Humorist (1834–1858).Footnote 69 Shortly after its performance, Saphir's comedy act was reprinted in Der Humorist and then in the Bavarian weekend special Münchener Conversationsblatt. “For the German, ladies and gentlemen,” Saphir commented, “the railway is a most welcome invention, an invention of the art of not being late, for five things are always too late in this world: remorse, fire extinguishers [Feuerspritzen], good thoughts, well-deserved rewards, and the German himself.” “The German,” Saphir continued, could be “characterized in a few words: the German people [Volk] is thoroughly educated and thoroughly poor [durstig], it lives on philosophy and sauerkraut … The German has great respect for the dead, he throws stones at the living and erects stones and monuments atop the dead, and in a century, Germany will look like a porcupine.”Footnote 70 This depiction evoked the misdirected intellectual indulgence of the philistine. Stuck in the past, the German was oblivious to the luxuries and customs of modern life, making do with philosophy and sauerkraut.

Nevertheless, Saphir contended, “the German invented three great things! But also, too late! He invented gunpowder, no-one shoots anymore; he invented the clock, and no-one knows what time it struck; he invented the printing press, nothing is being printed nowadays!”Footnote 71 Inasmuch as it existed, German innovation missed the mark. Saphir's mention of three great German inventions likely alluded to the centuries-old myth of the three great inventions of modernity, primarily associated with Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Bacon dubbed “the art of printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass” inventions that, despite their “obscure and inglorious” origins, had “altered the face and state of the world.”Footnote 72 The inventions’ unclear origins were typically seen as either signs of divine Providence or accidental impetuses of more systematic and deliberate innovation.Footnote 73 Although printing and firearms were generally attributed to the Germans, they were credited more for the rediscovery and improvement of these technologies than their initial invention, which, already in the sixteenth century, was traced to ancient China.Footnote 74 Finally, though the compass had never been considered a German invention, Nuremberg locksmith Peter Henlein (1485–1542) was widely credited as the inventor of the watch, for which he was commemorated in the Walhalla upon its inauguration in 1842, a fact of which Saphir and his audience may have been aware.Footnote 75

It follows that Saphir credited the Germans with inventions that were at the very latest early modern, and whose German origins were, in two out of three cases, contested. As made painfully clear by both Saphir and Marggraff, the Germans were mere observers in the tidal wave of technological development that swept over Europe in the nineteenth century. The railway especially underscored this disparity. In introducing the need for standardized timekeeping, it left the German, upholder of Henlein's legacy, hopelessly tardy.Footnote 76 Saphir's taunt was doubly ironic, for it was demonstrably untrue that noone printed, shot, or kept time anymore. On the contrary, it was the tremendous advances in all three areas that rendered any contribution the Germans may have had initially long forgotten. Like Marggraff, Saphir indicated two levels of the German's inadequacy. The German was unsuccessful as an innovator and modern professional. But on a more fundamental level, he was unselfaware, oblivious to the demands of fast-paced modernity, and unable to grasp the arbitrary changeability of its customs and norms.

A few weeks after it was published, Saphir's passage on German character was reproduced by a liberal journal based in Naumburg almost verbatim, excepting a few slight but notable adjustments that subtly transformed the message. In the revised version, the German had invented the printing press, yet he was the one being pressured; he had invented gunpowder, and was the one being shot; he had invented the clock, and yet knew not himself what time it was.Footnote 77 This version offered the bitter yet redeeming explanation of foreign exploitation. It was not the German's untimeliness that was at fault so much as his naive integrity, which allowed foreign rivals to reap the profits of his ingenuity and even use it against him. The German's anachronistic thoroughness and depth left him vulnerable to emasculation at the hands of more modernly shrewd, less deserving forces.

Alongside food, the erection of monuments was also a recurring theme in depictions of German backwardness. Whereas Saphir poked fun at the excessiveness of German monuments, Weber made a point of the Germans’ reluctance to commemorate national achievements: “Constantine's triumphal arches, the columns of Pompey and Trajan, or those such as in Place Vendôme, are hardly imaginable here; so, we keep our money in our pockets and take comfort in the fact that great men have erected a monument aere perennius Footnote 78 within our memory .… We are better-suited for makeshift monuments, from clay dolls—true and simple, like a German!—to pyramids and obelisks, six feet high at most.”Footnote 79 In lieu of larger-than-life monuments, continued Weber, Germans turned to commemorating their individual selves in portraits: “I do not, in fact, know of a nation where there are so many portrait painters as among the Germans! Is it vanity or German domestic comfort [Gemütlichkeit]? I believe it is the latter.”Footnote 80 It is plausible that Weber was alluding to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's (1749–1832) commentary on the subject written some decades earlier. Hoping for better monuments in the coming nineteenth century, Goethe lamented the German inclination to erect “columns … altars, obelisks and the like,” when “a good marble bust [was] worth more than any architectural structure erected in someone's honor and memory.” Busts could have medals made after them that could then be distributed among friends and had the further advantage of being themselves transportable, added Goethe. They could serve as “the noblest ornament of apartments” and be spared the wear and the vandalism that afflicted public monuments.Footnote 81 Goethe's praise of medals and busts is similarly inverted in the illustration of Lorenz Kindlein, who boasts a bust in his own sleepy image.

An entire series was dedicated to the topic of monuments in issues 11–14 of the FB, with illustrations by Carl Spitzweg.Footnote 82 Published in Munich in 1845, this series especially should be taken in the context of the Walhalla's inauguration in 1842. Perhaps the most ambitious tribute to date to German cultural figures, the Walhalla elicited a wide public response both within and beyond the German territories.Footnote 83 Several aspects of its conception and reception are relevant for the present discussion. First, the idea of building a pantheon of great Germans came after similarly conceived pantheons in London and Paris. Though grander in scale, the Walhalla was more peripheral in its location and less stately, commemorating an eclectic assortment of historical figures rather than state officials.Footnote 84 Second, as selective as it was expansive, the Walhalla's initial catalog of great Germans infamously excluded Martin Luther. In its attempt to foster a sense of German identity, the Walhalla, a passion project of King Ludwig I (1786–1868) financed from his private funds, became a jarring testament to the disjointedness of German nationhood. The pretense of exhaustiveness and the extent of Ludwig I's personal involvement featured center stage in the Walhalla's controversial public reception.Footnote 85 Third, notwithstanding its grand scale, the Walhalla is ultimately a museal collection of portrait busts, or as Heine described it, “a sanctuary of marble skulls.”Footnote 86 Finally, it was the only national pantheon in Europe to include women, though these were confined almost exclusively to royals and saints.Footnote 87

All of these aspects seem to be implicated in the FB's series “Die Monumente,” which opened with a “call to the German public” as follows: “It is a regrettable sign that in our time, which works so tirelessly and zealously towards the honorable recognition and decoration of deserving men—most fittingly through monuments following their death—a number of truly great men and women—the pride of our fatherland and the envy of neighboring nations—have until now been overlooked, indeed, nearly forgotten!” This wrong was now to be righted, the opening proclamation continued, with the help of the undersigned self-nominated selection committee, which undertook to present the brief biographies of notable, unrecognized Germans to the German people. The accompanying “monument-drawings,” it was clarified, were to be taken as a formal invitation to “the public, addicted to monument donations, to make splendid contributions to promote these great works.”Footnote 88 The four-part series proceeded to honor four fictional dead Germans. More mobile and reproduceable than even marble busts, the drawings were ironically of larger-than-life, full-body monuments, with a scale indicating a height of more than twenty meters. Despite the opening statement's indication to the contrary, no women made the cut. As we shall see, the mention of “truly great men and women” was a conscious disparagement.

First in line for overdue commemoration was Michel Knecht (“servant”), born 1452 in Erfurt, for inventing the bootjack. The fittingly named Knecht was an inn porter whose duties included removing the boots of “foreigners” (Fremden). After much effort and contemplation, Knecht freed humanity of the ancient difficulty of removing stuck boots with his invention of the bootjack, named Stiefelknecht to preserve his memory. Knecht himself did not benefit long from his own invention because he died shortly after, “the victim of his former profession,” from an inguinal hernia.Footnote 89 The accompanying “monument-drawing” (see Figure 3) illustrates the unfortunate professional hazard that cost Knecht his life—a nightcapped Michel Knecht is perched on a pedestal with an illustrated plait, which depicts a knight kicking a servant's backside as he struggles to remove his boot. Such was the hernia-inducing predicament of the inn porter, indicates the caption, “until the year MCCCCLII [1452].”

Figure 3. The “monument-drawing” of Michel Knecht.

The subsequent “monument-drawings” in the series went along similar lines. Those commemorated were, in order of appearance: Jean Jacques Fracas, a haughty, vain Elsassian youth of “true German origin” who invented the tails (Frack in German);Footnote 90 Wilhelm Gotthelf Heinrich Korkbaum (“cork tree”), who, inspired by his “collection of all misprints in German books since the invention of print,” invented the Rebus before dying of “brain desiccation”;Footnote 91 and, last but not least, the celebrated virtuoso “terpsichore” Franz Zwirn (“yarn”), who invented the “sweet vacillation between the cozy [gemütlich] German and piquant Polish elements” that was the Polka, “which no girl's heart could resist.”Footnote 92

Two masculine types emerge from this array of fictional German inventors. The first is the dreary, excessively diligent, and professionally unsuccessful Spießer or philistine, embodied by Michel Knecht and the inconceivably dull Wilhelm Korkbaum. The second is, uncharacteristically, the fashionable dandy. Yet the Elsassian Fracas, inventor of the tails, was actually French. Zwirn, the inventor of the Polka, was German, but his invention was not. The Polka took Europe by storm in the 1840s and was widely attributed to a Bohemian “farm girl” who had come up with the steps in a spontaneous burst of creativity, as reported by the Viennese Sonntagsblätter in July 1844.Footnote 93 Both Fracas and Zwirn ironically blur the boundaries between masculine production and feminine consumption, elevating fleeting fashions to the status of timeless inventions. Beyond being laughably trivial, their commemoration as great inventors betrays the selection committee's profound misunderstanding of the impermanent nature of modern fashions.

The various representations of the philistine German—the poor poet caught unawares by modernization; the uncompromisingly thorough, orderly Spießbürger; or the rural, food-loving simpleton—all reflect highly gendered national insecurities among the German middle classes in the early nineteenth century. The overarching stereotype was of a German who was behind the times, financially incapable, and naive, whose integrity and thoroughness failed to adequately equip him for the challenges of the day. It was precisely at those things expected of men that the German failed—being a socially and professionally capable provider and agent of progress. In almost none of these representations is the German contrasted with, positioned alongside of, or likened to a woman. Though emasculated, he is not effeminate, nor sexual in any way, failing to partake in modern industrial production and unable to indulge in or understand the luxuries of consumerism. Left out of the economic cycle altogether, he is confined to a preindustrial, domestic existence.

Too Masculine: The Quixotic German

Although the sleepy philistine who retreated to the secure comforts of his home was a common stereotype of German character, an alternative representation of the German offered the stark contrast of an all-too-eager warrior who charged at the enemy headlong. Embodying this duality, the Deutsche Michel at times slipped out of the dressing gown and into shining armor.

The “original” Deutsche Michel, it was claimed, was Hans Michel Elias von Obentraut (1574–1625), a cavalry general who had fended off Spanish troops in the Thirty Years War. Legend had it that his courageousness was etched so deeply into the memory of the Spanish that they were the first to refer to him as the Deutsche Michel.Footnote 94 A little-known figure at the time, Obentraut was heroized in 1846 in the book Der Deutsche Michel. Aus den Zeiten des dreißigjährigen Krieges by Prussian conservative George Hesekiel (1819–1874).Footnote 95 The first in a four-part series on “German heroes,” Hesekiel's book enshrined the origin-story as a counterweight to the philistine image.Footnote 96

An article dedicated to Obentraut as the original, heroic Deutsche Michel also came out in the FB in the early weeks of 1846.Footnote 97 It is probable that it predated Hesekiel's book. Either way, both works indicate a broader contemporary attempt to remasculinize this collective personification of the German man. Obentraut's legacy was that of a bellicose soldier who had been cunning on the battlefield and unflinching in the face of death. The contrast with his nightcapped successor, caught unawares by modernity, could not have been more pronounced. As recounted in the FB, Obentraut fended off Spanish troops against all odds by attacking them in their sleep.Footnote 98

Rather than a champion of the Protestant cause, Obentraut is represented in the FB as protector of the Germans in the face of the Spanish threat, “a power before which Germany—indeed, the whole of Europe—trembled.” His loyalty to the Protestant King Frederick V of the Palatinate (1596–1632) is contrasted with the self-serving cowardice and decadence of the latter, whose troops were “defeated on the white mountain as he himself was enjoying a merry banquet.”Footnote 99 Sealing Obentraut's heroic fate were his dying words to Tilly, the Catholic general and Bavarian legend who defeated him:

Tilly requested to see the dying hero, and when he was led to him, he confessed how sorry he was for the brave sword [Degen], even though he had stood opposite him in grave battle. To which Obentraut gestured at his bleeding wound and replied to the Field Marshal: “In a garden such as this, one picks roses such as these.” … Ever since, the Deutsche Michel has been on everyone's lips, though only a few know why. It has become a slur, which we happily put up with, so long as Hans Michel Obentraut's crowd does not die out in our fatherland, that noble tribe which knows how to wield a sword [Degen] with a strong fist, which strikes where one must, which teaches the German way to foreign hired swords, and which fights to the death for justice and faith.Footnote 100

This portrayal cast Obentraut as the German tragic hero of modernity. Obentraut's character is consistently linked to the epee (Degen), a weapon suited for dueling—yet he dies of a bullet shot by an unknown sniper.Footnote 101 His heroic masculinity was, after all, ill equipped for modern times. A valorous, loyal-to-the-death general whose courageousness was no match for modern weapons, he was lightyears away from the ideal of the professionally capable, respectable bourgeois man.

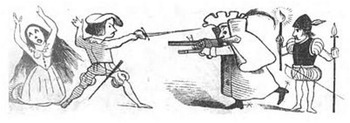

The piece on Obentraut was a flash of solemnity in an otherwise whimsical FB. Elsewhere within the journal's pages, the premodern, quixotic hero was no less made fun of than the nightcapped philistine, typically depicted as dying a nonsensical, self-inflicted death.Footnote 102 Such was the fate that befell the forbidden lovers Eduard and Kunigunde, protagonists of a satirical ballade who were both shot to death by the madly jealous, and by implication non-German, Fernando.Footnote 103 A telling illustration (see Figure 4) features a fiercely protective Eduard, a hysterical Kunigunde behind him, pointing a sword at his rival. Fernando charges forward unperturbed, aiming two rifles back at him. As with Obentraut, Eduard's swordsmanship could not avail him in the face of a firearm.

Figure 4. Eduard on the left, facing Fernando, in “Eduard und Kunigunde.”

Common to both Eduard and Obentraut was their irrationally unyielding loyalty, whether to a patron, a country, or a woman. This was the quixotic German's most distinguishing trait. His chivalry invoked a mixture of romantic images of medieval knighthood and aristocratic notions of hereditary privileges and duties that tied masculinity to valor, courage, and self-sacrifice.Footnote 104 This masculine ideal had long since lost currency and become the stuff of nostalgic parody. The invention of the firearm centuries earlier had indeed been one of the factors contributing to its decline.Footnote 105 Yet this ideal was also surprisingly enduring. Its ritualization in the duel, which survived criminalization in western and central Europe, enjoyed numerous revivals even as it attracted social ridicule.Footnote 106 In the German fraternities of the restoration period (1815–1830), debates on the social legitimacy of duels reflected intense contestation of what sort of honor German masculinity prescribed.Footnote 107 As an entirely voluntary engagement in life-risking violence, the duel collided with Enlightenment notions of masculinity that championed rationality, sensibility, and self-control, which had also become the tenets of middle-class respectability.Footnote 108

The quixotic German's chivalrous loyalty put him at a particular disadvantage as a modern suitor. The second volume of Weber's Dymocritos, a loose assortment of musings, many of them on gender, formulated this injustice:

Come now! all you beautiful and not-beautiful [women]! and scatter flowers, and build altars in honor of the Germans or Celts at whom you probably wrinkle your nose when a Frenchman licks your hand—it was Germans who led you out of Egypt and liberated you, just as marriage continues to liberate you … it was knights who alternately proved your high worth with the sword [Degen], and knew as little of the divine rights of man [des Mannes] as they did of the divine rights of kings—knights fought giants, dragons, and windmills for the rewards of love [Minnesold], they robbed, abducted, and ravished, in the belief that you could only be won by force, at which the depraved world of today—laughs. The knights elevated you to the level of goddesses and ideals … The recognition of women themselves as regents, the high veneration of the virgin, of which the Gospel knows not a word, seems to have derived from those [old-German] concepts of the special sanctity of [women].Footnote 109

By learning the arbitrary ways of the ladies, the Frenchman charmed them at the expense of more worthy candidates and betrayed the masculine code of honor. Weber linked the Frenchman's promiscuity and undeserved sexual appeal to his fashionableness: “Women are the primary need of the French, as is the case with all quick-witted people, precisely because they are quick-witted; French customs have spread everywhere, and ladies happily pursued those men of wit, who just happened not to direct their wits to their heads.”Footnote 110

The hypermasculine, overzealous, and fervently loyal German, who had ennobled women and liberated them from enslavement and polygamy in ancient times, was an unwelcome suitor by the standards of feminized modernity. Chivalry was of little worth in a world where the main predictor of success was the ability to satisfy women's rapacious material appetite. “Women value men as they would any article of fashion,” joked Saphir in his “humorous lecture.” “Eve thought something of her husband because he was modern, the latest fashion; she tried out the first man ever worn, but man is out of fashion now, for every common woman has one.”Footnote 111 If men generally were old news, what did that spell for the “always too late,” decidedly unfashionable German?

The new bourgeois ideal of matrimony was something of a masculinity test for a man's ability to first find a match, and then satisfy his wife's sexual, emotional, and financial needs. As put by George Mosse in his seminal study on modern masculinity, “The idealized platonic love of a noble lady that was supposed to spiritualize knighthood was now made commonplace through the monopoly exercised by the institution of marriage.”Footnote 112 This transition, however, and the shift in power relations that came with it, was tortuous. Mosse's study has demonstrated how the search for a suitable partner was a test of one's physical attractiveness and general desirability in a ruthless arena of masculine competitiveness.Footnote 113 Yet exacerbating this trial of masculinity were the conflicting demands that determined masculine desirability in the first place. Taming one's hypersexual, animalistic masculinity was considered a central requirement for married life that also intersected with class distinctions. A smoothly running marriage was what distinguished respectable, self-controlled middle-class men from their lower-class peers, who presumably failed to abstain from improper behaviors such as cheating and battering. These considerations did not necessarily align with sexual desire, which was often decoupled from marriage altogether.Footnote 114 Upon finding a partner, the married man's masculinity was not affirmed by the contrast provided by his feminine wife, nor by the sexual union his marriage consummated, so much as by the testament a steady marriage gave to his success as a well-rounded man in all areas of life—professional, financial, intellectual, emotional, and sexual—criteria that were often at odds with one another.Footnote 115 Overtly misogynistic representations of women in the German 1840s were repeatedly linked to the anxieties and frustrations associated with marriage.Footnote 116 The shopping-obsessed, impossible to satisfy housewife was also a recurring female type in the FB.Footnote 117 Consumerism and fashion were the foremost symbols for the feminine threat to modern man's masculinity, exemplifying an unfulfillable female desire that set men up to fail. As put by Felski, “The economic struggle for power is intertwined with and mediated by erotic relations between women and men and between women and commodities.”Footnote 118

It was precisely this impossible trial of masculinity that the fashionable Frenchman circumvented. An attractive, unreliable suitor, he reaped the benefits of both matrimony and bachelorhood, absorbing the cost of neither. A group of illustrations by Carl Stauber (1815–1902) in the FB features an Italian, a German, a French, and an English landscape artist, in that order, each with a corresponding rhymed caption.Footnote 119 The contrast between the French and the German artist is most apparent in their relationship to the respective subjects of their paintings, resonating contemporary inconsistencies surrounding sexual relations and matrimony. The German is, as ever, thorough and earnest. Under a simple parasol perched on a rock, in travel clothes and with a pencil in hand, he draws the likeness of a flower with loving care, foregoing the impressive landscape of mountains and rivers around him (see Figure 5). “He who faithfully observes you, nature! on a miniscule scale,” reads the caption, “embraces you on a large scale as his bride.” The German's monogamous devotion to his subject, nature, is manifested in his loving fascination with its every detail, which transcends any transient infatuation with its dazzling beauty.

Figure 5. The German artist in “Die Künstler.”

The French artist, in contrast, is entirely detached from what he is trying to capture. On a larger-than-life canvas, he paints screaming children fleeing a burning cottage struck by lightning with uncanny realism, as the scene unfolds before his very eyes (see Figure 6). Standing in a firm power-pose, indifferent to all but the aesthetic aspects of his surroundings, he says in both broken German and perfect French, “For the Frenchman, nothing is impossible.” Though tall and bearded, with muscular arms, he is also slim waisted and in women's shoes.Footnote 120 The French artist's androgyny is most apparent in his fashionable attire. In blatant contrast to his German equivalent, his relationship to the subject of his painting is one of exploitation. He views the scene as nothing more than a narcissistic reflection of his own skill, which he displays with tasteless extravagance.

Figure 6. The French artist in “Die Künstler.”

The German artist's undying loyalty found an idealized expression in his art. Other portrayals did not reward the quixotic German as generously. An illustrated limerick about an impassioned yet unrealistic German revolutionary published in the FB directly links his sexual frustration to his political and professional failings. On both fronts, his naive loyalty is ridiculed. Resentful and humiliated, the revolutionary reminisces about how he “sang of girls and wine, of the fatherland and loyalty,” only to have the girls break his heart “laughing,” the wine redden his nose, and the fatherland laugh at his pain and “mock the poet's ecstasy.” The tortured poet then wielded his pen against the regime and was consequently exiled. As depicted in one of the accompanying illustrations (see Figure 7), the newly exiled poet sits scowling, fists clenched childishly, with a quill in his mouth that recalls Spitzweg's Der arme Poet.Footnote 121 Outraged and resentful, he swears “world annihilation,” splits a model globe in half and curses “the modern direction.”Footnote 122 Unlike the poet Kindlein, however, who politely allows modernity to trample all over him, the revolutionary poet is a grotesque example of masculine rage. Frustrated by his attempts to bring about modernity, he curses it. Although he is prepared to act and hardly risk-averse, the revolutionary's efforts are irrelevant and go hand in hand with his sexual disappointment, which is rendered laughable.

Figure 7. The disappointed revolutionary in “Weltschmerz.”

Mythologized as a war hero, caricaturized as foolishly lionhearted, or ridiculed as a sore loser, the quixotic German was the perfect mirror image of the philistine German, marking the opposite extreme of the same pendulum. While the philistine German was characterized by rural simplicity and domestic comfort, the quixotic German was associated with knightly aristocracy and self-sacrifice. If the philistine German was resigned and submissive, the quixotic German was confrontational against his better interests. Finally, where the philistine German was desexualized, the quixotic German was sexually frustrated. In comparison to his nightcapped alter ego, the quixotic German was both more redeemable and more ridiculous, but just as inadequate at meeting the demands of industrial modernity.

Conclusion

“Nature, ladies and gentlemen,” said Saphir in his “humorous lecture,” “is a novelist [Schriftstellerin], and a bad one at that, for her best work is—man! This work of nature, full of misprints and misconceptions, first appeared in raw form, then printed on a fig leaf, and then, as cultivation [Bildung] continued to prevail, it was engraved on animal skins, and only when civilization reached its peak was this work stiffly bound together in iron clasps.”Footnote 123 Saphir's metaphor placed industrialization at the center of modernity. The peak of civilization was the ability to manipulate metal on a massive scale. This technological prowess was not what made modernity so disconcerting, however, but rather its feminine corruption of man's authenticity. The feminized modernity that taunted the German man was just that—primal nature turned female novelist, whose capricious march forward contorted man, and masculinity as his essence, into an overprocessed reproduction of his original form.

The Germans’ relatively slow pace of industrialization contributed to German insecurities, but it does not emerge as their main underlying cause. Unflattering comparisons to England, the fastest industrializing European country, were made, yet they were not nearly as frequent nor as virulent as comparisons to the French. A long history of German–French rivalry and territorial disputes partly explains this asymmetry, but it does not explain the tangible sense of German inferiority and humiliation in the face of French fashionableness. On the contrary, wartime had provided a wealth of affirmations of German superiority and masculinity. In 1813, old-school, chivalrous German masculinity had triumphed over the effeminate, affected Frenchman.Footnote 124 Wartime even allowed for the remasculinization of the Deutsche Michel following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. As noted by Eric Hobsbawm, his inclusion in the Bismarck monument represented “both the innocence and simple-mindedness so readily exploited by cunning foreigners, and the physical strength he could mobilize to frustrate their knavish tricks and conquests when finally roused.”Footnote 125 Military triumph could monumentalize and heroize even nightcapped philistines.

It was the competitive, industrialized economy of peacetime that gave the fashionable Frenchman an unearned advantage, not only economically but sexually. It was not the Frenchman's effeminacy in itself that was intimidating, but his knack for intuiting and manipulating fashion's femininely arbitrary rules, thus elevating his social status while subverting the norms of bourgeois respectability and monogamy. Feminized modernity was his native terrain. It was also where the German's deficiency was most felt. Common to both the philistine and the quixotic German was their incomprehension of the trivial mannerisms and showy displays of banquets and ballrooms. The supposedly masculine traits celebrated in canonized German poets and warriors—profundity, earnestness, thoroughness, and integrity—were the same traits that rendered the German socially illiterate.

The conflicted image of the German man and the ambivalent nature of his masculinity can be easily overlooked or misinterpreted in the analysis of political and intellectual discourse from this period. Yet they are plain to see in those contemporary humorous sources that were oriented toward a politically, regionally, and confessionally diverse bourgeois audience. Humor, and particularly disparaging humor, was uniquely adapted to capturing and negotiating a self-image that flickered between pride and humiliation, sympathy and scorn, acclaim and ridicule. Its layered meanings convey complexities that are absent from more conventional sources.

At the same time, humor's reliance on allusions, tropes, and cultural codes provides a good indication of what bourgeois readers and viewers were expected to recognize, attesting to their prevalence. The extensive intertextuality between Weber, Saphir, and the FB points to a common language. Nightcaps, homely food, ill-conceived monuments, chivalrous knights, and fashionable Frenchmen effectively codified meaning in contemporary German bourgeois culture. Their encapsulation of the many contradictions and inconsistencies afflicting gender roles and German national identity can divulge valuable information for the historian. Appreciated in their full complexity and ambivalence, national and gender stereotypes emerge in humorous sources as more than ideologically motivated prescriptive ideals that served to petrify existing power imbalances. Whether self-deprecating or self-aggrandizing, they were also thick descriptive representations that helped make sense of an unstable reality. Taking this dimension of their social and cultural function into account is crucial to fathoming the full extent of their historical agency.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was supported by the Mandel Scholion Research Center at Hebrew University. The author would like to extend her heartfelt thanks to Professor Gal Ventura, Professor Moshe Sluhovsky, Professor Ofer Ashkenazi, and Margarita Lermann for their invaluable advice and insightful comments at various stages of this article's development; and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and incisive feedback.

Tamar Kojman is a PhD candidate at Hebrew University. She is a fellow at the interdisciplinary Mandel Scholion Research Center and the Minerva Richard Koebner Center for German History. She is writing her dissertation on “The ‘Apolitical German’ and the Question of German Statehood (1830–1880).”