In China's one-party bureaucracy, central directives – laws, commands, instructions and guidelines issued by the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the State Council – are the most important instrument of formal policy communication. While central directives are only part of a larger system of formal and informal communications within the bureaucracy,Footnote 1 they occupy a supreme position in the hierarchy of orders. When an agenda is issued as a central directive, it carries the collective authority of the entire central leadership. Furthermore, it will be vertically transmitted to local Party committees and governments, who possess the authority to mobilize all relevant departments to execute a mandate from the top. Mao Zedong's insistence that he must personally approve these directives before they could be issued is evidence of the political significance of central directives. Rival factions fought to push their personal agendas onto these directives, even amid the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 2

Since the 1970s, several studies have described the functions of central directives and the process by which they are drafted and disseminated. To date, however, no study has systematically analysed the language of these directives, despite their pivotal role in Chinese policy-making. Regarding the procedure of policy communication in China, the prevailing impression is that central authorities issue broad, vague guidelines and that ministries and local governments are left to interpret and flexibly implement central policies. For example, in their classic book Policy Making in China, Lieberthal and Oksenberg state: “The higher levels frequently give vague directives.”Footnote 3 Similarly, Brandt and Rawski commented: “These guidelines become encapsulated in catchy slogans that gain wide currency in official circles and also among the Chinese public. These slogans, and the policy guidelines that inform them, direct the flow of policy implementation at all levels.”Footnote 4

But this conventional portrayal presents a puzzle: How can a vast country, facing daunting challenges, be governed and transformed through catchy slogans and frequently vague expressions from the authoritarian leadership?Footnote 5 In my earlier work, I proposed a revisionist account of how policy communication and law-making works in China. Ambiguous directives are one striking feature of the system – but they do not present the entire picture. In fact, as this study shows, the CCP-state leadership issues a mixture of ambiguous and clear commands. Excluding logistical communication, since 1978 more directives have been clearly worded than vaguely worded.

More precisely, I highlight three politically salient varieties of central directives. Each serves a distinct function: grey (ambiguous about what can or cannot be done), black (clearly states what can be done) and red (clearly states what cannot be done). Grey directives encourage flexible policy implementation and experimentation, black ones strongly endorse and scale up selected initiatives and red ones forbid certain actions. Together, this mixture of ambiguous and clear decrees forms a system of adaptive policy communication, allowing central authorities to selectively grant flexibility and enforce discipline.

In my earlier proposal of this revisionist model of policy communication and law-making, I presented a few illustrative examples of each variety of directive.Footnote 6 Taking the next step, this study operationalizes my model by systematically classifying thousands of directives into the theorized categories of grey, black and red. My analysis includes a total of 4,923 directives issued by the State Council (Guowuyuan 国务院) and the General Office of the CCP Central Committee (Zhonggong zhongyang bangongshi 中共中央办公厅; or the Central Office for short) from 1978 through 2017, which covers the administrations of Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. I employ techniques from automated text analysis to classify this large volume of directives according to a systematic set of coding procedures that will be introduced later. This measurement effort goes beyond impressionistic observations and the subjective interpretation of a small number of texts. My dataset of these central directives produces original insights into the party-state's policy communication across domains and across functional categories. I also compare directives issued by the central state and Party leadership, as well as the evolution of grey, red and black directives from Deng to Xi.

The Art of Commands

How are formal orders communicated in China's top-down political system? Michel Oksenberg, perhaps the first US-based scholar to address this basic question, wrote in the China Quarterly in 1974: “The behaviour of the Chinese Communists is often explained in terms of their guerrilla past, and rightly so. But the rulers of China are also inheritors of centuries of sophisticated organizational practices, and nowhere is this more evident than in the issue of written directives.”Footnote 7 These directives make up what he called the “vertical formal channels within the bureaucracy,” which overlap with other non-written and informal channels such as meetings, visits and personal communications.

In a follow-up study in 1978, Lieberthal, Tong and Yeung detailed the functions of directives and the process of drafting and transmitting them to lower-level officials. In their words: “These documents are used to serve a range of functions – from communicating authoritative decisions to stoking up a policy discussion to circulating reference materials to citing positive and negative models for approbation or criticism.” Although written some 45 years ago, their core insight endures: “There is a great deal of flexibility built into the Central Document system…they should be followed in spirit rather than to the letter.”Footnote 8

Since then, numerous studies have made references to “vague,” “broad” or “ambiguous” guidelines in Chinese policy-making.Footnote 9 In Bureaucracy, Politics, and Decision-making, Lieberthal and Lampton state that Chinese bureaucrats routinely operate and bargain under “vague guidelines” in which “the definitions of the limits of authority…are often intentionally left vague.”Footnote 10 On economic policy-making, Brandt and Rawski agree, writing: “National policies emphasized broad principles or parameters rather than specific instructions or regulations.”Footnote 11 Vogel characterizes Deng Xiaoping's slogan “socialism with Chinese characteristics” as “marvelously vague.”Footnote 12 A few recent studies suggested that central authorities issue “intentionally vague” directives so that lower-level functionaries can implement policies flexibly.Footnote 13 These arguments dovetail with a prolific literature on Chinese adaptive governance and policy experiments that have been credited for the CCP's authoritarian resilience and economic dynamism.Footnote 14

This descriptive literature provides a necessary starting point and valuable background on Chinese policy communication,Footnote 15 but it is either based on impressionistic observations or on a small number of documents. My study is the first attempt to systematically analyse the wording of all central directives issued since 1978, including laws and legislations, with a focus on their ambiguity and clarity. Using this data, I am able to empirically answer these questions: Are Chinese directives in fact frequently vague? When are they vague, and why?

My measurement efforts are theoretically motivated. Vague messages are not unique to the Chinese bureaucracy. In communication studies, Eisenberg defines “strategic ambiguity” as situations where vague language “is not a kind of fudging, but rather a rational method used by communicators to orient toward multiple goals.”Footnote 16 For instance, some companies use ambiguous language in their mission statements to accommodate diverse stakeholders.Footnote 17 Similar to the China-specific literature above, these observations about the functions of ambiguity are correct – but incomplete. They fail to note that ambiguity alone is not enough for adaptive communication but must be combined with selective clarity, as some issues require flexibility while others demand discipline.

In my earlier work, I applied concepts from complexity and systems thinking to identify the bureaucratic foundations of China's economic transformation – this includes outlining a theory of adaptive policy communication.Footnote 18 Enabling adaptation does not simply mean letting go of control; instead, as complexity theorists Axelrod and Cohen remind us: “Variation provides the raw material for adaptation. But for an agent or population to take advantage of what has already been learned, some limits have to be placed on the amount of variation in the system.”Footnote 19 More simply put, effective adaptation requires striking a balance between variety and uniformity – having some range of flexibility and experimentation, but not too much.Footnote 20 If instructions were always vague and there were no limits on flexibility, the result would be confusion and chaos rather than adaptation.

Thus understood, adaptive communication calls for a strategic mixture of ambiguity and clarity that varies depending on the complexity of problems and leaders’ priorities. In the context of the Chinese bureaucracy, central directives come in three salient varieties:

• Grey directives neither forbid nor endorse. They are ambiguously worded and/or contain language that explicitly encourages flexibility and experimentation.Footnote 21

• Black directives endorse by clearly stating what can and indeed should be done. Expressed in modern organizational language, they have the effect of scaling up.

• Red directives forbid by clearly spelling out what cannot be done and identifying the rules that must be strictly enforced. They serve to discipline.

To illustrate, I discuss below one example of each type of command:Footnote 22

Grey. In 1979, the State Council issued Directive No. 1, “Guidelines on the Development of Commune and Brigade Enterprises,” a foundational directive that jumpstarted the process of rural industrialization in the 1980s. This directive neither endorsed nor forbade the establishment of collective enterprises (initially known as commune and brigade enterprises). Instead, it urged local governments to be “self-independent” and explore solutions “according to local conditions” and “based on need and feasibility,” provided that they abided by socialist principles. Such language encouraged local officials in parts of China to experiment cautiously with collective enterprises.

Black. The economic success of collective enterprises caught the central leadership, including Deng Xiaoping, by surprise. Once the State Council was convinced that collective enterprises worked, it elevated the initiative to a national policy by issuing a black directive: Directive No. 1, “Guidelines on Rural Work in 1984.” This directive proclaimed in affirmative language: “Collective enterprises are part of the collective economy, so we should help refine and improve them.” Afterward, the number of collective enterprises jumped dramatically nationwide – in other words, the experiment scaled up. In China, clearly worded edicts are powerful amplifiers of outcomes, for better or worse.

Red. In 2011, the State Council issued Directive No. 1, “Decision on Accelerating the Regulation of Water Consumption.” This directive drew a bright “red line” of 670 billion cubic metres of water for total annual consumption; this was translated into quotas that were distributed by region, industry and product. Compliance with these quotas was incorporated into officials’ evaluations and violations of this red-line policy would incur punishments. Red directives are meant to be clear and firm, with little or no wiggle room.

Decades ago, Lieberthal, Tong and Yeung intuited that flexibility is built into China's system of directives, but they did not specify how. My model of adaptive political communication identifies a key mechanism: the combination of grey, black and red directives enables central authorities to grant flexibility, scale up initiatives and enforce discipline.

Measuring Commands

I now proceed to a larger challenge: operationalizing my model – that is, turning my concepts and categories (grey, black and red) into measurable items across all the directives issued in the post-Mao era. Operationalization presents many practical challenges: How do we determine whether a directive is grey, black or red? How do we translate the concept of “grey” into observable and measurable attributes? How do we measure the frequency of grey, black and red directives across a large number of documents in an objective, systematic way? I briefly describe my methods below.Footnote 23

Corpus. I analyse a total of 4,923 directives issued by the State Council and the Central Office, the two most powerful governing bodies in China's political system.Footnote 24 The source is Beida fabao 北大法宝, the most comprehensive online database of Chinese laws and regulations. Each document indicates the office that promulgated the directive, when the order was announced, and when it went into effect; this is followed by the full text. I choose to treat each directive, rather than paragraphs and sentences within it, as my unit of analysis because, in practice, such documents are interpreted as a whole rather than in parts.

Time period. My dataset from 1978 through 2017 covers the consequential period of China's rise, beginning with Deng's historic decision to “reform and open” and extends to Jiang, Hu and the first five years of Xi's leadership (2012 through 2017). It does not cover Xi's second term, which underwent significant shifts, including Xi's removal of presidential term limits in March of 2018 and heightened US–China tensions.

Automated text analysis. Automated text analysis (ATA) refers to the “systematic analysis of large-scale text collections” with the aid of computer programmes.Footnote 25 Having humans read and classify large numbers of documents one by one would be subjective, inconsistent and exceedingly time- and labour-intensive; in short, it is neither effective nor feasible. With ATA, machines perform the task according to a set of rules programmed by the researcher. In recent years, China scholars have applied ATA to analyse large volumes of social media posts and news reports, and such efforts have yielded original descriptive insights.Footnote 26 My study is the first attempt to apply ATA to policy communication within the bureaucracy.

Hybrid classification method. My next step involves selecting from among appropriate ATA techniques, which can be broadly divided into three approaches: (1) the dictionary method: specify keywords and count their frequency; (2) supervised learning: humans code a partial “training set” of documents and then computers imitate this classification in the entire set; (3) unsupervised learning: machines group documents based on underlying characteristics that are not specified by the programmer. Of the three techniques, none is inherently superior; whichever is better is a question of fit with the task at hand. As ATA methodologists Grimmer and Stewart underscore, “One of the most important lines of inquiry is identifying effective ways to combine previously distinct methods for quantitative text analysis.”Footnote 27

The nature of my text – central directives – presents unique challenges. Most existing analyses are conducted on social media posts (which are short) or on press statements (which are meant to convey one clear attitude, e.g. positive or negative). Chinese policy directives, however, are highly variegated in length, ranging from one paragraph to many pages. A single directive may address multiple issues and may simultaneously express ambiguity and clarity in different parts. Therefore, it is not feasible for human coders to read these directives and consistently determine whether they are grey, black or red. Given these characteristics, the commonly used supervised learning method is not a good fit.

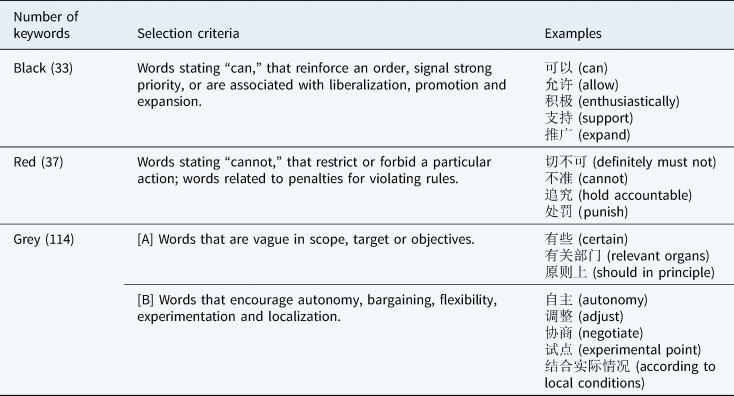

Instead, I adopt a hybrid classification method. First, using a dictionary method and based on a close reading of more than 190 directives,Footnote 28 I specify a list of 184 words that indicate whether a directive signals ambiguity and flexibility (grey), affirmation (black), or restrictions (red). Operationalizing the concept of “grey” proved to be more challenging than those of “black” and “red” because, in practice, ambiguity is expressed in two forms: first, as words that are vague in scope, target or objectives; and second, as words that encourage autonomy, bargaining, flexibility, experimentation and localization. Table 1 lists my operational definitions of the three categories and their corresponding keywords.

Table 1. Examples and Criteria for Selecting Keywords

Compared to supervised learning, the benefit of this approach is that it is possible to code each document based on pre-specified and countable criteria rather than on a coder's overall impression. I calculate an adjusted score of grey, black and red keywords in each directive, taking into account the number of keywords, the total number of words in a document, and the number of characters in both the keywords and the entire document.

Second, I incorporate the K-means algorithm,Footnote 29 an unsupervised learning method, which computes the threshold for classifying the 4,923 directives into a given category based on similarities in their keywords. In other words, instead of having human researchers subjectively select thresholds for classification, the algorithm selects the threshold by accounting for all of the keywords.

Neutral directives. A further methodological step was creating a fourth category of directives, which I call “neutral.” These are documents that contain none or few of the keywords selected and thus do not meet the automated threshold for classification into the theoretically salient categories of grey, black or red. Neutral directives can be interpreted more as serving logistical functions that are necessary for maintaining daily operations and less as policy signals. They include, for example, administrative acknowledgements and notices informing about meetings, reports and new committees.

Grey, Black and Red

Having classified the directives according to the procedures described, we now explore some descriptive patterns. Among the 4,923 directives, 23 per cent are grey, 20 per cent are black, 14 per cent are red and 43 per cent are neutral. It is not surprising that almost half are neutral, as running a large bureaucracy requires frequent logistical communication. Of the remaining three categories, grey takes up the largest share (23 per cent). But if we combine black and red, 34 per cent of the directives are worded clearly for the most part. This means that, contrary to popular impression, Beijing has issued clear directives more frequently than vague ones.

Below is an example of a directive classified as grey. Titled “State Council's Response Regarding the Request to Establish a China (Hangzhou) Cross-regional E-commerce Experimental Zone,” it was issued in 2007 by the State Council and addressed to the Zhejiang provincial government and the Ministry of Commerce. The grey keywords, which are bolded, include both vague words (e.g. “relevant organs” [youguan bumen 有关部门] and “gradually” [zhubu 逐步]) and words that encourage flexibility and experimentation (e.g. “explore” [tansuo 探索], “adjust according to the times” [shishi tiaozheng 适时调整] and “experimental zones” [shiyan qu 试验区]). It contains only a few black keywords and no red keywords. Based on these characteristics, the algorithm classifies it as grey.

[Document name] 国务院关于同意设立中国(杭州)跨境电子商务综合试验区的批复

[Score] Grey: 0.13, Black: 0.03, Red: 0

[Policy domain] New industries

[Sample passage] 三、有关部门和浙江省人民政府要努力适应新型商业模式发展的要求,转变观念和工作方式,积极做好服务,大力支持综合试验区大胆探索、创新发展,同时控制好试点试验的风险。 要在保障国家安全、网络安全、交易安全、进出口商品质量安全和有效防范交易风险的基础上,坚持在发展中规范、在规范中发展,为综合试验区各类市场主体公平参与市场竞争创造良好的营商环境。 试点工作要循序渐进,适时调整,逐步推广。四、浙江省人民政府要切实加强对综合试验区建设的组织领导,健全机制、明确分工、落实责任,有力有序有效推进综合试验区建设发展。

In the remainder of this article, I omit neutral directives and discuss only the theoretically salient categories of grey, black and red to highlight patterns relevant to policy guidance and to streamline my discussion.

Variation across Policy Domains

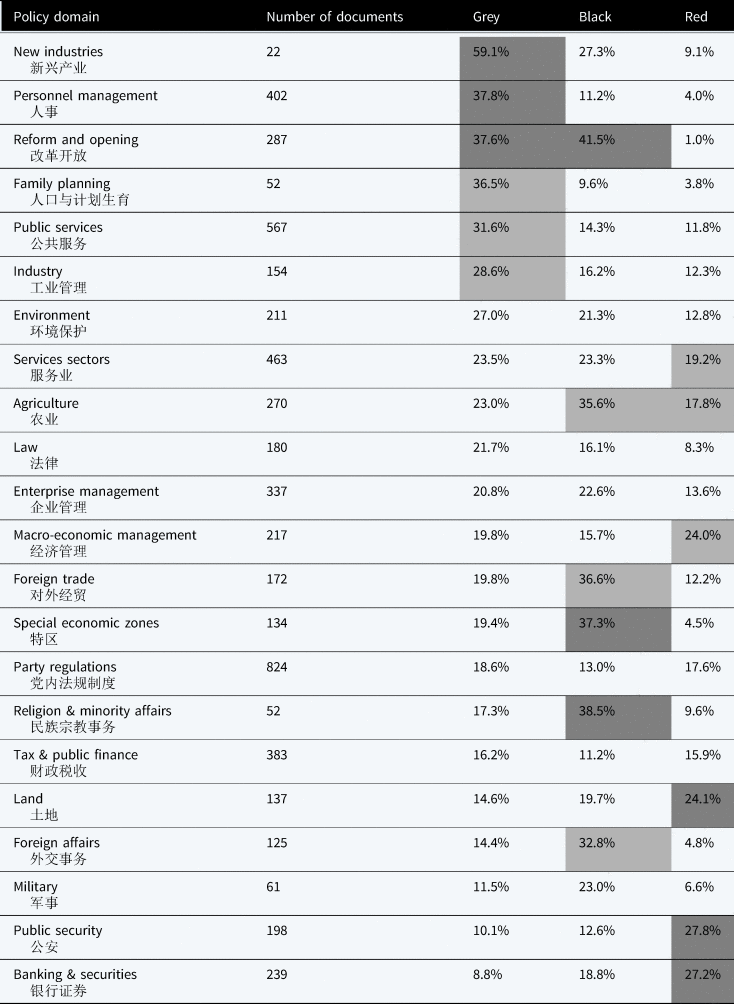

Table 2 shows the distribution of grey, black and red directives across 22 policy domains.Footnote 30 I highlight three observations that are most relevant to the proposed adaptive functions of ambiguous and clear commands.

Table 2. Grey, Black and Red Directives across Policy Domains

Notes: The domains with the six highest shares of black, red and grey documents are shaded.

Grey directives. The domain with the highest share of grey documents is that of new industries (59 per cent); it leads over other policy areas by a considerable margin. “New industries” include e-commerce, ride-hailing, big data and artificial intelligence, to name a few examples. As these industries were novel, state regulators barely noticed or knew about them, let alone desired to regulate them (note that my period of analysis, ending in 2017, is before the crackdown on big tech companies under the “common prosperity” [gongtong fuyu 共同富裕] campaign in 2021).

New industries represent a policy context of uncertainty.Footnote 31 The first directive referring to “internet information services” was promulgated by the State Council in 2000, and it defined these services as “providing information over the internet and designing webpages for fees.”Footnote 32 Clearly, at the time, central regulators did not foresee the rise of e-commerce and the digital economy. The small share (9 per cent) of red directives appeared only in the early 2000s and were centred on controlling potentially subversive internet content. This descriptive pattern is consistent with an observable implication of my theory: policy flexibility tends to prevail in uncertain, novel policy domains. This proposition may subsequently be tested by developing a measure for uncertainty.

Black directives. Policies in the domain of “reform and opening” (which includes trade liberalization, attracting foreign direct investment, agricultural liberalization and regional development plans) have the highest share of black directives (42 per cent). Because the primary goal is liberalization, these directives are predominantly affirmative; they also provide flexibility in implementation (38 per cent are grey) and contain few restrictions and penalties (only 1 per cent are red).

Red directives. Directives that clearly spell out restrictions are most prevalent in public security (28 per cent), banking and securities (27 per cent) and land management (24 per cent). This pattern is consistent with my theoretical proposition that central authorities are most likely to draw red lines on issues pertaining to political stability, national security and common-pool resources. Finance is a highly regulated activity and, under Xi, worries about financial risks sharpened. “We must not neglect…hidden danger. Safeguarding financial security is a strategic and fundamental matter for China's social and economic development,” Xi warned financial regulators in 2017.Footnote 33 Land is another case in point. Since local governments rushed to sell land for revenue in the 2000s, the national pool of arable land has been steadily depleted. In 2008, the Ministry of Land and Resources announced a binding mandate to maintain 1.8 billion mu (200 million hectares) of total arable land; this was followed by a series of regulations to enforce Beijing's “1.8-billion-mu red line.”Footnote 34

Variation across Functional Categories

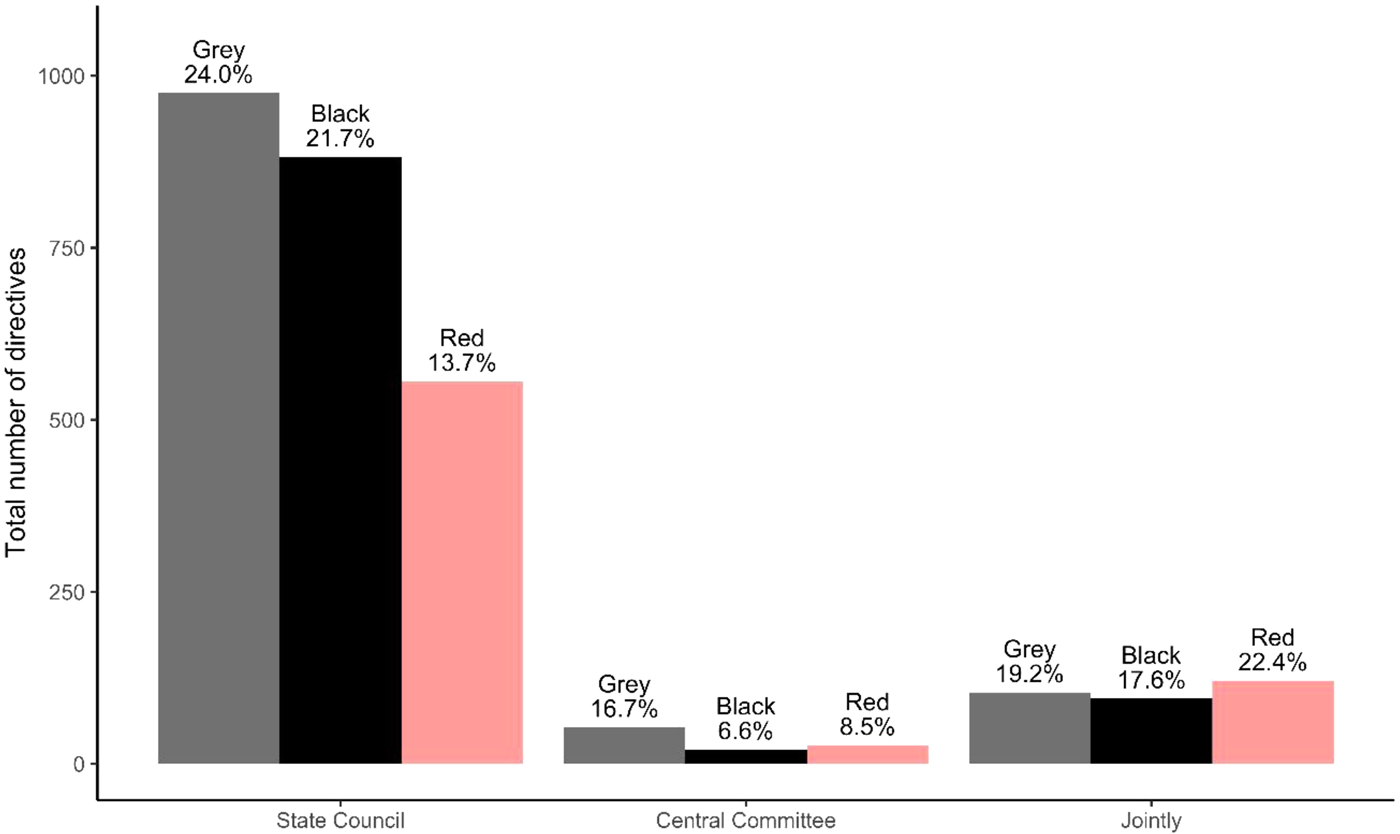

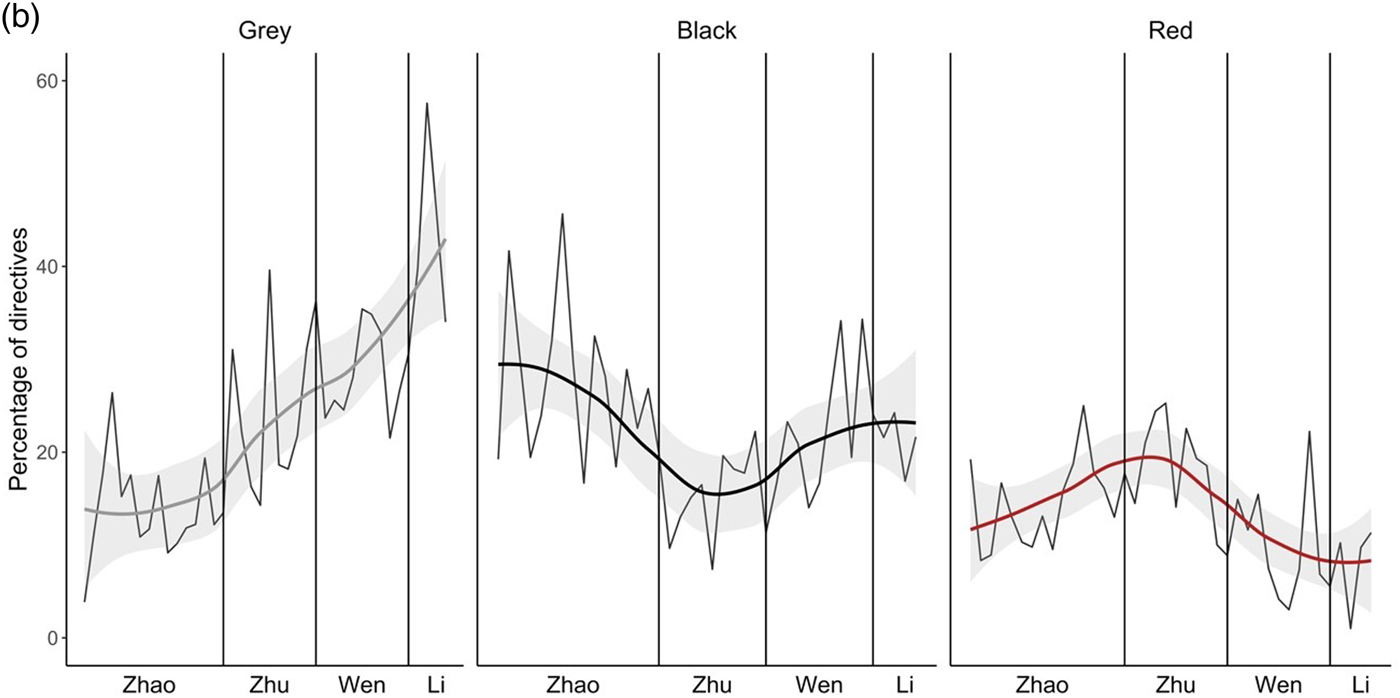

Oksenberg identifies four functional categories of directives in the Chinese state bureaucracy: “laws and regulations” (fagui 法规), “administrative rules” (guiding 规定), “notices” (tongzhi 通知) and “responses to requests (for guidance from ministries and local governments)” (pifu qingshi 批复请示). To his list, I add two categories: “suggestions” (yijian 意见) and “others.” “Others” is a residual category that includes clarification (shuoming 说明), explanation (jieshi 解释) and highlights (yaodian 要点), for example.Footnote 35 With a dataset, we may now know the distribution of directives by functional category (Table 3) – a basic feature that was previously undocumented – and the distribution of grey, black and red directives within each category (Figure 1). The largest category is “notices” (52 per cent).

Figure 1. Grey, Black and Red Directives by Functional Category

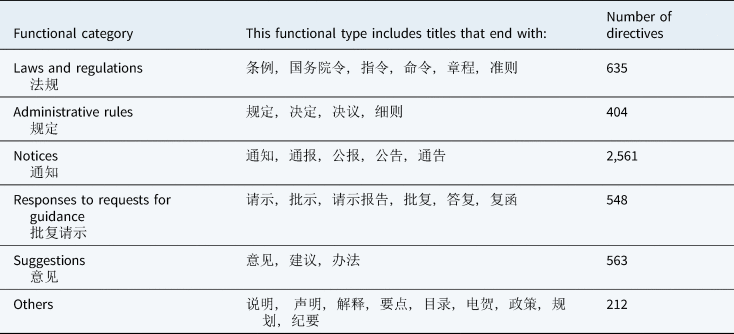

Figure 2. Directives Issued by the State Council, the Central Office, and Jointly

Table 3. Number of Directives in Each Functional Category

The category “laws and regulations” contains the largest share of red directives (28 per cent) and the smallest share of grey directives (5 per cent), indicating that this group serves mainly to set clear restrictions with generally little flexibility. “Administrative rules” has the second highest share of red directives (18.1 per cent), but contains a larger share of black directives (21 per cent) than does “laws and regulations” (7 per cent). This suggests that the “administrative rules” category serves not only to restrict but also to endorse and encourage certain measures.

Not surprisingly, “suggestions” has the highest share of grey directives (37 per cent); it also contains a high share of black directives (30 per cent) and a low share of red ones (8 per cent). In other words, directives in the “suggestions” category generally provide policy flexibility and affirmation more frequently than they do restrictions. “Responses to requests” is the category with the highest share of clearly worded directives (i.e. red and black combined). This suggests that when central authorities respond to requests for guidance from their subordinates, they tend to give “yes/no” responses, though 21 per cent of such documents are still classified as grey.

In summary, not all directives in the “laws and regulations” category are red (clear and restrictive) and not all of those in the “suggestions” category are grey (ambiguous and flexible); rather, each category contains mixtures of grey, black and red directives – albeit in different proportions.

The State Council versus the Central Office

Next, I explore directives issued by the top state and Party organ respectively. As Lieberthal, Tong and Yeung note, whereas the State Council “tends to concentrate on issues that are narrowly technical or specialized in nature” (as it leads the administrative hierarchy),Footnote 36 the Central Office exercises supreme authority over political matters. When a given agenda concerns both governance and politics, the State Council and the Central Office will jointly issue a directive.Footnote 37 My dataset allows us to track the types of directives issued by each hierarchy.

Since 1978, 4,065 directives (83 per cent of the total) were issued by the State Council, 317 (6 per cent) by the Central Office, and the remaining 541 (11 per cent) were jointly issued. In other words, the State Council issued the vast majority of central directives. Nearly all (97 per cent) of the Central Office's directives involve Party regulation, which includes issues such as the Party constitution, rules on Party leadership, monitoring within the Party, education on political theory, management of leading cadres, etc. The State Council issued directives in 21 policy domains, aside from Party regulation. Jointly issued directives cover all 22 policy domains, with 96 per cent involving Party regulation. This overall pattern is consistent with the formal division of authority: the State Council is in charge of governance while the Central Office controls political and Party issues.

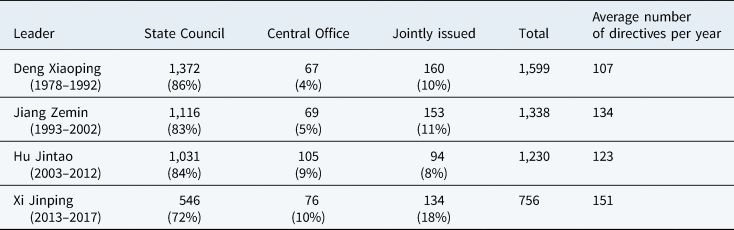

It is well known, however, that since taking power Xi has steadily sidelined the premier and expanded the power of the Party to economic and social policies, making himself the “chairman of everything.”Footnote 38 My data is consistent with this qualitative observation: under Xi, the State Council has issued a smaller share (72 per cent) of central directives than under Deng, Jiang or Hu (83–85 per cent). Simultaneously, the proportion of jointly issued directives (18 per cent) under Xi is the highest since 1978 (Table 4).

Table 4. Central Directives from Deng to Xi

Excluding neutral directives, grey directives are the most common type of directive issued by the State Council and the Central Office. About 22 per cent of the directives issued by the State Council are black, compared to only 18 per cent in jointly issued directives and 7 per cent in Party-issued directives. This suggests that the State Council tended to be slightly more affirmative than the CCP leadership. Jointly issued directives contained the largest proportion of red directives (22 per cent), followed by those issued by the State Council (14 per cent) and the Central Office (9 per cent).

Evolution from Deng to Xi

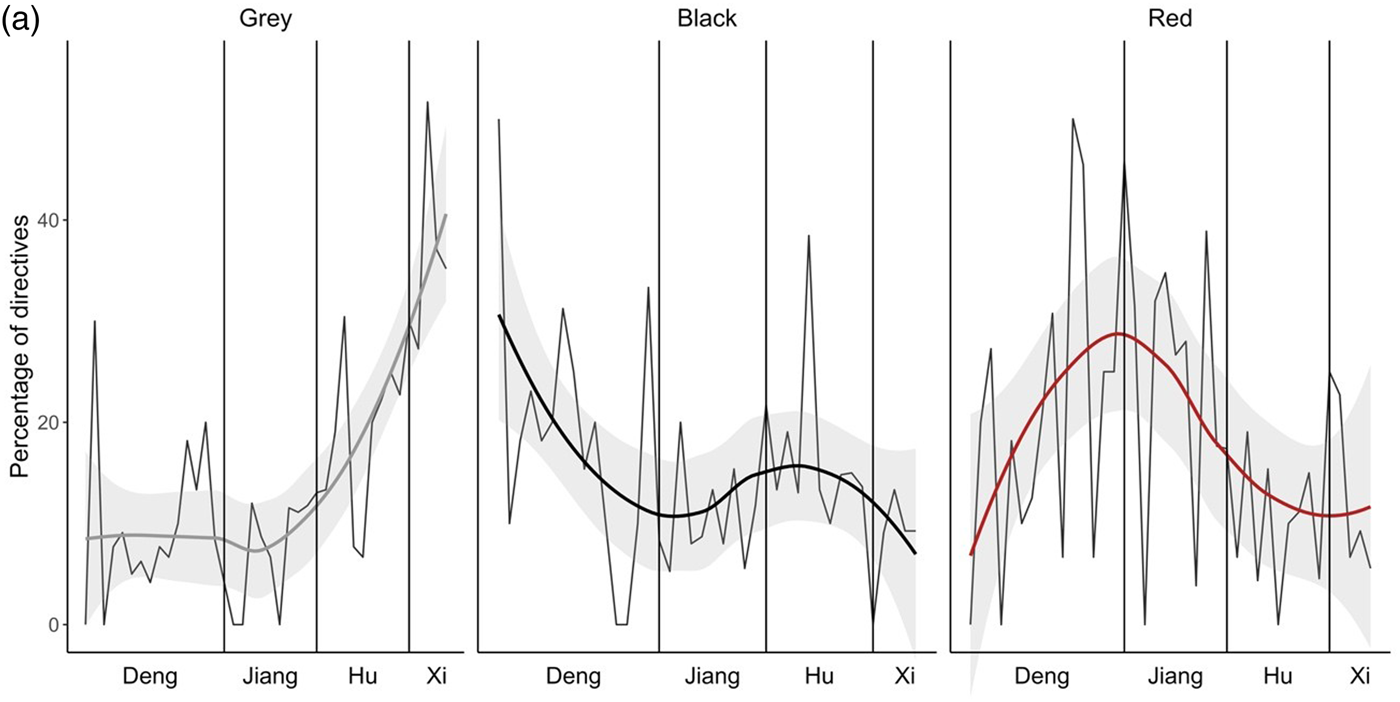

How have Beijing's commands evolved during the post-Mao era? In this section, I explore the evolution of policy communication under four successive Party leader–premier duos: Deng Xiaoping–Zhao Ziyang, Jiang Zemin–Zhu Rongji, Hu Jintao–Wen Jiabao and Xi Jinping–Li Keqiang. Figure 3a shows the grey, black and red directives issued by the Central Office and jointly by the Central Office and the State Council; that is, these are directives pertaining to politics and Party regulation. Figure 3b shows the directives issued by the State Council, which concern matters of governance.

Figure 3a. Party-issued and Jointly Issued Directives from Deng to Xi

Figure 3b. State Council-issued Directives from Deng to Xi

Before interpreting the descriptive patterns below, some caveats and limitations should be noted. Xi's administration may not be directly comparable with those of his predecessors for several reasons. As earlier noted, while the Jiang–Zhu and Hu–Wen administrations have generally been known as partnerships, Xi has sidelined his premier, Li Keqiang. Particularly in recent years, the two have sometimes openly expressed different policy stances (for instance, over COVID-19 policy). Hardly anyone refers to the current administration as Xi–Li, and I do so in the subsequent section only for semantic consistency. Furthermore, the share of a given category of directives is a function of the total number of directives issued. As my dataset only covers the first five years of Xi's tenure, the Xi–Li administration has fewer total directives than its predecessors (see Table 4). My data only tell us the number and share of directives across the categories of grey, black and red. Their particular meaning under each leader and in each policy domain requires closer contextual reading. The value of these descriptive patterns lies in suggesting potentially interesting and previously unnoticed questions for investigation.

Four patterns stand out. First, the distribution of and changes over time in grey, black and red directives shown in Figures 3a and 3b are similar, which suggests that the communication patterns of the state and Party leadership are consistent across administrations. Second, the share of grey directives has increased over time and peaked in 2015 during Xi's tenure, which may be surprising given his authoritarian turn. Third, black directives were most dominant under Deng. Fourth, red directives peaked under Jiang's administration.

Deng–Zhao: (Following convention, I refer to Deng as the de facto paramount leader during this period as he ruled behind the scenes through his protégés.Footnote 39) As the architect of China's reform and opening, Deng not only liberalized the economy but also profoundly revamped the bureaucracy by introducing decentralization, meritocracy and values of pragmatism. In doing so, he laid down the foundation for an adaptive style of governance that drove China's capitalist growth for the next 35 years. His pragmatism was encapsulated in one of his famous maxims: “Crossing the river by touching the stones.”

Given this reputation, one might intuitively expect Deng and his premier, Zhao Ziyang, to exhibit the highest share of grey directives. Yet the results show the opposite: most of their directives delineate clear rules about what could be done (26 per cent were black) and could not be done (15 per cent were red), and only 14 per cent of their directives were grey. Three of the most frequently used keywords under Deng were “approve,” “can” and “must not” – in other words, yes and no. Given that officials had just suffered the trauma of ideological attacks during the Cultural Revolution, it may have been that Deng had to give them clear instructions about what they could and could not do, in order for communist apparatchiks to change course decisively and embrace market reforms.

Under Deng, the two domains with the highest proportion of black directives were foreign affairs (51 per cent) and reform and opening (48 per cent). This is consistent with Deng's dual approach to reform and opening: on the international front, he fostered China's integration into the global capitalist economy while domestically he freed up markets and private initiative. Overall, the patterns under Deng remind us that more ambiguous commands do not necessarily equate to more adaptive governance – the right mixture of directives depends on the leadership's defining priorities in a given time.

Jiang–Zhu: Taking office after the Tiananmen crisis and Deng's Southern Tour, Jiang and Zhu's legacy was defined by their mission to build a “socialist market economy.” They sought to expand market reform and create a modern regulatory apparatus that would complement China's integration into the global capitalist economy. Their ambitions to strengthen the central government's macro-economic management capacities appear to be reflected in a greater share of red directives in certain domains: land (56 per cent), banking and securities (37 per cent), economic regulation (28 per cent) and public finance (20 per cent). Two of the most significant structural reforms overseen by Premier Zhu Rongji were fiscal recentralization and restructuring of the banking and financial system.Footnote 40 The high share of red directives may reflect the dramatic expansion of new regulations, restrictions and penalties in these areas. All the directives on new industries were red under Jiang–Zhu because, as discussed earlier, central regulators at the time did not foresee that the internet would open up transformative business opportunities, so they focused only on censorship.

Hu–Wen: In Saich's words, if Jiang–Zhu's leadership was a period of “renewed reform [that] laid the foundation for unprecedented wealth,” then that of Hu and Wen is often regarded as “a time of drift.”Footnote 41 Under Hu–Wen, we see a rising trend in the share of grey directives that continued into the Xi era. These grey directives were concentrated in industrial management (53 per cent), human resources (41 per cent), family planning (40 per cent) and special economic zones (40 per cent). One policy domain with a notably high share of clearly worded directives was public security (16 per cent black and 26 per cent red). To put this in context, compared to industrial management (6 per cent black and 16 per cent red), Hu–Wen's directives on public security were expressed in firmer language, both affirmative and restrictive. This may reflect their administration's priority on “maintaining stability” by increasing the presence of policing forces and curbing a rising number of protests linked to economic issues.

Xi–Li: Finally, we come to Xi Jinping. Many experts have characterized Xi's leadership as a period of “authoritarian revival” and “personalistic rule.”Footnote 42 He has centralized personal power and tightened ideological and political control. Yet despite this reputation, the share of grey directives peaked during his tenure. This pattern is consistent in the directives issued by the State Council (under Li Keqiang) and the Central Office (under Xi) (see Figures 3a and 3b), which suggests it is not the State Council alone driving this pattern. Furthermore, grey directives were spread out across many policy domains, including family planning (100 per cent), military (100 per cent), new industries (71 per cent), public finance (68 per cent) and reform and opening (58 per cent), which suggests a broad pattern.

One preliminary interpretation of these patterns is that Xi's authoritarian turn, at least up until 2017, may have coexisted with selective adaptive governance. Despite Xi's marginalization of Li, the State Council still issued 72 per cent of the central directives, thus the high share of grey directives may reflect the State Council's attempt to provide flexibility (though this pattern is also consistent with Figure 3a, directives issued by the Central Office and jointly issued directives). Journalistic reports described Xi as a micro-manager.Footnote 43 But at least in public, Xi has claimed that he has not abandoned local experimentation. At the B20 Summit in 2016 he pronounced, “China forged a unique development path through the approach of ‘crossing the river by feeling the stones’.”Footnote 44

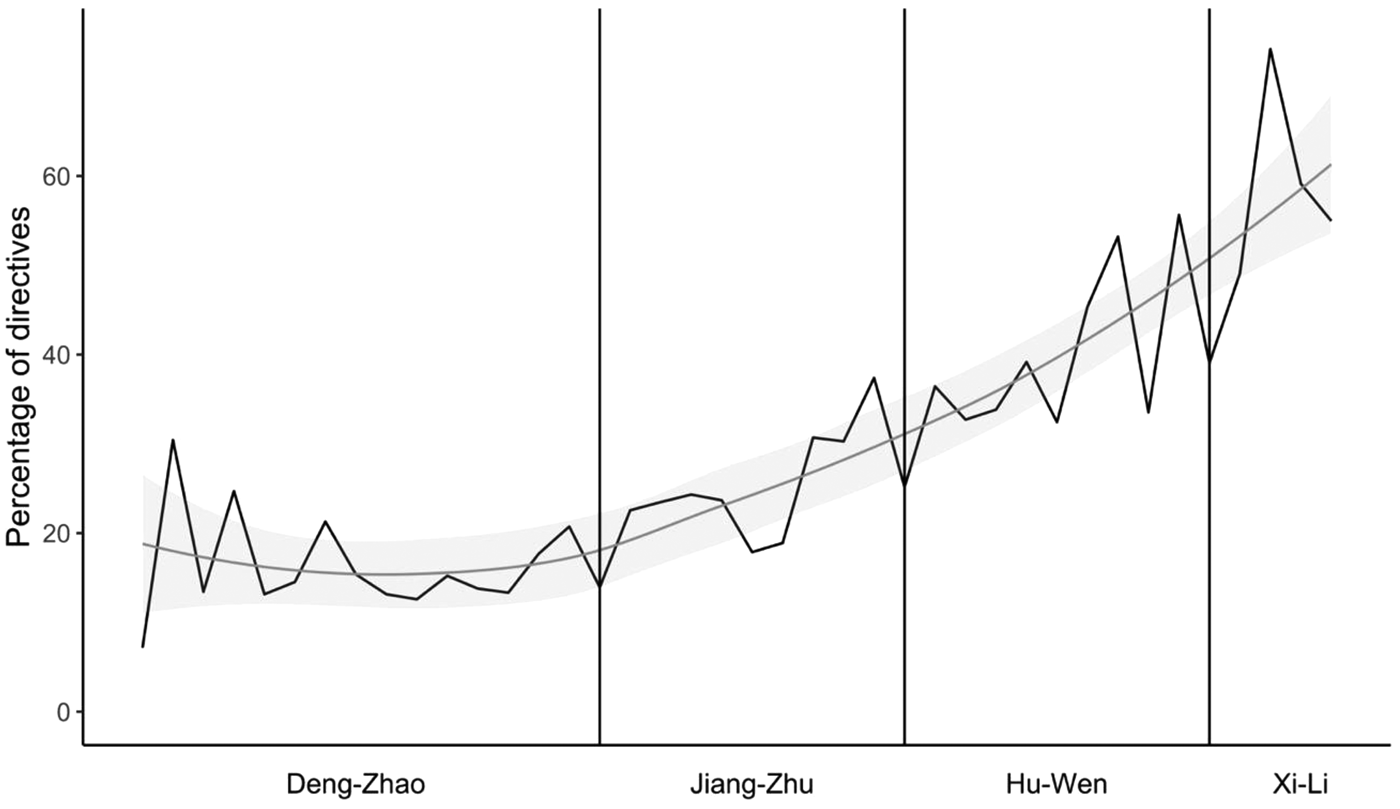

More recently, in a speech on common prosperity in 2021, Xi exhorted the bureaucracy to adapt and experiment with ways to reduce inequality without hurting entrepreneurial incentives. Appointing Zhejiang province as his imperial pilot, he instructed in Deng-like language: “You must seriously consider Zhejiang as a demonstration case for common prosperity, encourage other regions to explore effective pathways according to local conditions, review lessons and implement solutions gradually.”Footnote 45 Figure 4 shows the percentage of directives containing words related to experiments and pilots.Footnote 46 Similar to Figures 3a and 3b, it shows a steadily rising pattern after Deng that peaks under Xi.

Figure 4. Directives Containing Keywords on Experimentation

Notes: This figure includes directives issued by the Central Office, the State Council and jointly issued directives.

But while Xi has sometimes issued commands urging experimentation, whether lower-level functionaries have responded positively is a different question. Xi's intense anti-corruption campaign has had a paralyzing effect on officials, who would rather do nothing than take initiative and incur political risks, inspiring the term “lazy governance.”

I should also reiterate that this dataset only covers the first term of Xi's leadership, up until 2017. Since then, some of Xi's policy attitudes have changed, with technology being one example. From 2012 to 2017, the central government enthusiastically supported various forms of new industries such as e-commerce and granted these sectors significant latitude. The directives in this domain were predominantly grey (71 per cent) and contained no red ones. In December 2020, however, central regulations began to crack down on big tech companies. Thus it is possible that directives issued after 2017 may diverge from Xi's first five years in office. Those after the 20th Party Congress in October 2022, when Xi officially assumed his third term as top leader, could diverge further. He has insisted, for instance, that the bureaucracy stick to his “zero-COVID” policy “without wavering.”

Conclusion

This article advances a revised model of Chinese policy communication, focusing on central directives – laws, commands and guidelines that flow from the very top. It posits that, contrary to popular impression, the flexibility of Chinese policy-making is not simply achieved by “frequently [giving] vague directives.” Rather, adaptive governance is achieved through a combination of three varieties of directives – grey, black and red – with each serving a distinct function respectively: granting flexibility; affirming; and restricting. Based on this model, I have presented a pilot attempt at classifying the directives issued during the post-Mao period into theoretically salient categories. There is plenty of room for revising and improving my methods and discovering new patterns.

At this pilot stage, my objective has been to open up new agendas and explore methods in data generation. First, I bring attention to the empirical study of policy communication and law-making. The gap between policy goals and outcomes is well known in China studies, encapsulated in the folk saying “where there is a policy from above, there is a counter-policy from below.” Policy communication, I have argued, presents a middle step between policy formulation and policy implementation.Footnote 47 After decisions and policies have been formulated by the leadership, they must be communicated to a vast bureaucratic apparatus before they are implemented. This middle step, however, has thus far received little systematic analyses. There is ample potential for using automated text analysis to examine the language of central commands.

Second, through this project I hope to advance the literature on Chinese adaptive governance both theoretically and empirically. In their seminal volume, Heilmann and Perry argue that the CCP's exceptionally adaptive governance is influenced by its revolutionary past.Footnote 48 Their argument is correct, but past experiences do not necessarily result in adaptive governance unless the right “meta-institutions” – defined as “higher-order structures and strategies that facilitate adaptive and learning processes” – are in place.Footnote 49 The mixture of clear and ambiguous commands is one meta-institution that allows the CCP leadership to selectively enforce discipline and grant flexibility. This framing takes China out of the box of “Chinese exceptionalism” and connects it with the universal theme of adaptation-enabling organizational designs,Footnote 50 which has been explored beyond China and by practitioners. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that theories of adaptive governance, typically illustrated by case studies, should and can inform data collection.

Many questions remain to be explored: How do central directives vary across finer policy domains and change as the context of a given policy issue changes? How have lower-level governments responded to directives from the top? Why does the Xi–Li administration have a high share of ambiguous commands and calls for experimentation despite Xi's authoritarian turn? Has policy communication in Xi's second five-year term changed significantly from his first? From 2022 onward, following Xi's complete consolidation of personal power, what changes might we expect to see? Will adaptive governance continue or end? I hope this initial empirical effort and the findings presented here can motivate future research into the theme of adaptive policy communication.

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for exploratory funding support.

Yuen Yuen ANG is the Alfred Chandler Chair of Political Economy at Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of two award-winning books, How China Escaped the Poverty Trap and China's Gilded Age.