Introduction

Recent historical studies have asserted Southeast Asia agency in the pre-1500 era, in contrast to prior histories that have advocated Southeast Asia's cultural if not economic and political dependency on India, China, and the Middle East. In this older view Southeast Asians modeled their civilizations on their more ‘advanced’ neighbors. New ‘borderless’ approaches have focused on Southeast Asia's connectivity rather than dependency in challenging past Indian Ocean historiography. Herein regional political hegemony over early water transit in the eastern Indian Ocean region is now conceived as less a factor than the networks of multiple maritime trading and religious diaspora that shared a variety of ship, coastal, and port space (Mukherjee Reference Mukherjee2011, Reference Mukherjee2014; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2015).

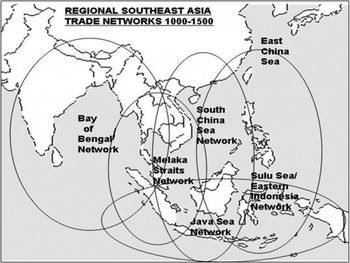

Against previous scholarship that was prejudicial to China, the Middle East, and South Asia-based agencies and regional spheres of influence, newly available shipwreck archaeological recoveries in the Southeast Asia maritime region have especially allowed the re-reading of epigraphic and textual sources to better detail the Bay of Bengal, Straits of Melaka, and Java and South China Seas as extended ‘borderless’ but highly networked extended eastern Indian Ocean passageways between South Asia and China. These multi-centered transit zones included the Bay of Bengal southern, central, and northeast South Asia coastlines; modern-day Myanmar, the Malay Peninsula, and Sri Lanka; the Straits of Melaka region linking Singapore, Sumatra, and north and east coast Java; the overlapping Java Sea eastern Indonesian archipelago and South China Sea regions that included the Vietnam and west and south Borneo coastlines, and southern China, with ongoing eastern links to the Sulu Sea region via the Philippines (Acre, Creese, and Griffiths Reference Acri, Creese and Griffiths2011; Miksic Reference Miksic2013; Schottenhammer and Ptak, eds. Reference Schottenhammer and Ptak2006) (See Map 1).

Map 1: Extended eastern Indian Ocean activity zones

Multidisciplinary revisionists address the flow of various contemporary material objects, spices, silk, cotton textiles, coinage, as well as Chinese and Southeast Asian ceramics and Middle Eastern glassware through South Asia and Southeast Asia to China via overland and maritime passageways, and iron to Java and other Indonesian archipelago regions that were iron deficient (Green Reference Green2000; Green Reference Green2007: 200; Bielenstein Reference Bielenstein2005; Wade Reference Wade2009). As examples, eastern Indonesian archipelago island societies still use c. 1400 South Asia heirloom cotton textiles imported from the Gujarat, south India, Sri Lanka, and the upper Bay of Bengal in regional rituals (Barnes Reference Barnes1989). The mid fourteenth century account of the Middle East sojourner Ibn Battuta provides detailed accounting of these and other commodities in transit and their destinations (Gibb Reference Battuta and Gibb1929). The contemporary Java Nagarakertagama court chronicle defined the eastern Indian Ocean regions with which Java regularly traded: Nusantara was the physical space where Java's monarchs were said to have had direct political interests, but without sovereign control; Desantara, or the “other countries”, were even more distant and lay beyond the conceptual trading core. Many of these ‘countries’ were polities with which Java's monarchs had diplomatic and cultural exchanges as reported in the following Nagarakertagama passage:

“….The above [inclusive Nusantara] are the various regions protected by His Majesty; On the other hand, the Siamese of Ayutthaya and also of Dharmanagari [Nakhon Si Thammarat on the central Malay Peninsula], Marutma [Martaban, Burma/Myanmar, a lower Burma cultural and commercial center], Rajapura [Ratburi, southwest of modern Bangkok], as well as Singhanagari [Singhaburi, north of Ayutthaya on the Chaophraya river], Champa [south and central Vietnam], Cambodia, and Yawana [northern Vietnam] are always friends.” (Robson Reference Robson1995: 34)

A 1,200-year-old salvaged wooden vessel from the western edge of the Java Sea, known as the Belitung wreck (since it sank in Indonesian waters off the coast of Belitung Island), carried over 60,000 pieces of China's Tang dynasty-era ceramics, in addition to notable gold and silver artifacts that are partially represented in a Singapore National Museum display. One inscribed ceramic bowl provides the approximate time of the shipwreck: “the 16th day of the seventh month of the second year of the Baoli reign” (826 CE), which is thought to mark the date that the bowl was fired. The ship's cargo included numbers of these distinctive brown and straw-colored glazed ceramic ‘tea bowls’ — otherwise named after the Changsha kilns in China's Hunan province where they were produced for broadly based (as opposed to exclusively aristocratic) consumption (Henderson Reference Henderson1999, Reference Henderson2002; Krahl Reference Krahl, Krahl, Guy, Wilson and Raby2010).

The partially recovered Arab dhow vessel, sixty feet long, has a raked prow and stern likely built of African or Indian wood and was fitted with a single square sail. Notably the ship was not held together by dowels, as was the norm among contemporary Chinese and Southeast Asia-built ocean-going craft, but instead its planks were sewn together using coconut-husk fiber cord (Flecker Reference Flecker2001, Reference Flecker2002; Miksic Reference Miksic2009; Krahl et al. Reference Krahl, Guy, Wilson and Raby2010). In sum, the variety of cargo indicates that the vessel was transiting via the Straits of Melaka/Java Sea/South China Sea passageway to and from Baghdad carrying a variety of Indian Ocean products such as fine textiles, pearls, coral, and aromatic woods. Its cargo did not contain precious metals (notably much in demand silver), as China's port masters at that time guaranteed that China would not be drained of its precious metals. Thus, the mass ‘factory-like production’ of ceramics by five different China kilns for the export trade was an intentional state-coordinated enterprise. At that time transporting volumes of ceramics overland to the West via the Central Asia passage on camels or horseback was not suitably efficient. China's Tang rulers (618–907 CE) instead promoted the oceanic passageway, as it better suited China's profitable trade in ceramics.

The Changsha bowls are distinctive in their decorations, which anticipated the variety of their Indian Ocean marketplaces. The decorative motifs include Buddhist lotus symbols, as well as makara fish and Chinese calligraphy for Buddhists; geometric decorations and Quranic inscriptions for Islamic markets; and white ceramic ware and green-splashed bowls popular among Persian consumers (Fig. 1). One bowl is inscribed with five loose vertical lines, thought to be symbolic of Allah. There were 763 inkpots (as the Abbasid-era, 750–1258 CE, was notable for handwritten rather than printed texts), 915 spice jars (appropriate for the storage of the valuable Indian Ocean spices, including those of the Indonesia archipelago, that made their way to Middle Eastern marketplaces), and 1,635 ewers (spouted ceramic water vessels appropriate for water pouring) that were also in high demand in contemporary Middle Eastern markets (Hall 2010b).

Figure 1. Tang Shipwreck Chinese Ceramics c. 830, Singapore Asian Civilizations Museum (Photo: Kenneth Hall)

This and other recent shipwreck recoveries clearly indicate that regional political boundaries during the pre-1500 era were never absolute relative to Indian Ocean sojourning trade, traders, and various ‘men of ideas’ such as Ibn Battuta [who traveled in Asia from c. 1325–1354] and the Tang and Ming dynasty scribes who recorded and mapped the pre-1500 voyages, as these have been documented and detailed by recent archaeological recoveries from contemporary Southeast Asia port-sites. Collectively these contemporary sources lend credence to notions of variable networked ‘borderless’ east-west transits in the pre-1500 eastern Indian Ocean, and a sense of an inclusive Indian Ocean passageway that is portrayed in early Chinese maps (Miksic Reference Miksic2013; Wade Reference Wade2015, Reference Wade2016).

Sojourning and Residential Trade Communities in the Pre-1500 Southeast Asia Region

Clearly the modern day Southeast Asia region was a major oceanic transit zone and as well a destination on the pre-1500 international East-West ‘Maritime Silk Road’ connecting the Middle East, South Asia, and China. The Southeast Asia region's prominent maritime activity zones were product sources and marketplaces, as also short-term or longer term residential centers of sojourning traders and Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic clerics, artisans, and political dignitaries. Until the last decades of the twentieth century Western scholars tended to think of early Indian Ocean trade as based in contained regional political and port spaces adjacent to and distinct from regional upstreams and hinterlands. In contrast, revisionist scholarship has perceived the eastern Indian Ocean maritime regions as open sojourning spaces characterized by fluid borders among a series of networked centers and regions of production, marketing, and port and upstream/hinterland activities characterized by a variety of residential and periodic uses including commodity, human, and knowledge transfers (Calo Reference Calo2014; Wade Reference Wade2015; Lammerts, ed. Reference Lammerts2014). Current studies that address the inclusive eastern Indian Ocean realm have moved beyond thinking in terms of absolute societal boundaries to better understand the variability of early eastern Indian Ocean networked communities. What is now known as Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, among others, are modern spatially defined regional polities that are legacies of colonial-era boundary divisions that were intended to contain heterogeneous regional populations who had previously had greater opportunity for fluidity (Manguin Reference Manguin2002; Miksic Reference Miksic2013; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017b).

The eastern Indian Ocean region in the pre-1500 age was by nature an area of few impenetrable physical or human boundaries with extensive coastlines and riverine systems that connected upstreams and downstreams to a variety of coastal ports as depicted in early regional chronicles (Hall Reference Hall2001; Wade Reference Wade2009, Reference Wade and Kayoko2013; Gaynor Reference Gaynor2013). There was periodic change as one port-of-trade and its upstream was replaced as the ‘favored port/coastline’ due to variable internal and external circumstances. In this era population clusters were normally separated physically and by self-definition into distinct activity zones, often within a singular or allied network of coastline and river systems as perceived in the representative contemporary Chinese map (Fig. 2). There were rarely contiguous borders as regions were historically under-populated, especially on their peripheries, and political power was marked less by control of geographical space but by the number of residents a ruler could depend upon to remain loyal and who would share their resources for the common good or profit (Aung Thwin Reference Aung Thwin1983; Gommans and Leider Reference Gommans and Leider2002). Cultural crossovers were common, and newcomers were welcomed as additional human resources rather than as liabilities (L. Andaya Reference Andaya2008; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2010, Reference Lieberman2011) (See Map 2).

Figure 2. Fifteenth century view of the inclusive Indian Ocean maritime trade route from China to the West in Jia Dan's depiction of Zheng He's early fifteenth century voyages. (Adapted from “A Reconstructed Sea Chart of Zheng He's Maritime Route” in Mao Yuanyi's 茅元儀 The Treatise of Military Preparation (Wubei zhi 武備志) [c. 1621] (Park Reference Park and Hall2011))

Map 2. Southeast Asia c. 1000–1500

This fluidity differs from China's history that is concerned with the political consequences of overpopulation, disrespect for traditional societal hierarchy, and the administration of populations who reside within the inclusive boundaries of the chiefly agrarian Chinese state (Chaffee Reference Chaffee2006, Reference Chaffee and Hall2008; Clark Reference Clark1991, Reference Clark2015). By necessity a new China dynasty had to reconquer ‘rightful’ Chinese territory so as to fulfill Confucian expectations of those who claimed and then reestablished imperial control. In the Chinese aristocracy's mind, maritime activity was peripheral to China's agricultural landed core. By contrast, Southeast Asia's pre-1500 polities were relatively open, people-centered and underpopulated realms in which non-contiguous population clusters had considerable autonomy, including, if they wished, the opportunity to embrace new external commercial, religious, cultural, and political opportunities. The Southeast Asia region's population clusters were more fluid than those of China, as they were open to and embraced the periodic influx of new residents as resources who brought with them their own variety of negotiable cultural practices (Bronson Reference Bronson and Glover1992; Miksic Reference Miksic2013).

The following account of a Chinese merchant who traded in south and central Champa (Vietnam) coastline ports during the late twelfth century provides a window on the interactions among China-based officials, Southeast Asia port-of-trade rulers, and ‘foreign’ traders (especially south China diaspora merchants who had resettled in the Southeast Asia region) as it details the multiple networked relationships of a representative Chinese merchant sojourner:

“Wang Yuanmao was a Quanzhou [port-of-trade] man. In his youth he worked as a mere handyman in a [Chan] Buddhist monastery. His masters taught him how to read the books of the southern barbarian lands, with all of which he was able to become closely acquainted; and he accompanied sea-going junks to Champa. The monarch of that country admired his ability to read both barbarian and Chinese books, invited him to become a member of his staff, and gave him one of his daughters in marriage. Wang lingered for ten years before returning (to China), with a bridal trousseau worth a million strings of cash. His lust for gain became fiercer, and he next went trading [in the South China Sea] as the master of a sea-going junk. His wealth became limitless and both Prime Minister Lie Cheng and Vice-Minister Juge Tingrui formed marriage connections with him (through their children). In 1178 he dispatched his borrower [xingqian] Wu Da to act as head merchant [gangshou] on a ship setting out to [the Southern Seas] with a total crew of thirty-eight men under a chief mate. They were away for ten years, returning in the seventh moon of 1188, anchoring south of Luofu Mountain in Huizhou. They had obtained profits of several thousand percent.” (Yoshinobu Reference Yoshinobu1970: 192–3)

This Chinese account is consistent with the variety of regional evidence of the Jiaozhi Yang Vietnam coastline maritime network cited above, as this and other Chinese sources allow historians to achieve a better sense of the meaning and significance of the overlapping local and wider political, economic, religious, and societal extended eastern Indian Ocean regional settings. From the late Song dynasty era numbers of Chinese resident in the Southeast Asia region, like Wang Yuanmao, were acculturating into local societies, or negotiating relationships with their neighboring communities as these networked relationships were vital to their personal success. Wang Yuanmao's biography is notable not only for the accounting of his career as a sojourning entrepreneur, but also in its address to his foundational training in a Buddhist monastery that provided the educational and religious base for his subsequent successful commercial career. This accounting is consistent with new studies of Indian Ocean maritime diaspora communities that commonly find similar cross-references to a merchant sojourner's religious identity, indicating that religious affiliations were meaningful among Indian Ocean maritime diaspora communities (Clark Reference Clark1991; Mair and Kelley Reference Mair and Kelley2015). In several cases south China linked diaspora were noted to be variable patrons of Islam, while others subsidized shrines dedicated to the local divinity of their home port-of-trade, and those like Wang Yuanmao sustained temples in their residential ports and networked upstreams that were institutionally linked to south China Mahayana Chan/Zen Buddhist ‘mother’ temples. This key ingredient of variable cultural affiliation among Chinese sojourning diaspora is overlooked in exclusively economic and political focused studies, as these ignore the vital role that Chinese maritime diaspora assumed in the creation of the new ‘borderless’ culturally networked communities in the regions to China's south, as shared cultural/religious exchanges with local populations were foundational to collective Chinese and local ethnicity economic and political opportunities (Clark Reference Clark and Hall2011; Gunn Reference Gunn2011; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017b).

These new cultural options set in motion wider regional change, less due to replication of China and more to a ‘localization’ in which the resident community made modifications of their cultural practices as appropriate to indigenous needs and opportunities. Such Southeast Asia localizations commonly reinforced new highland-lowland and upstream-downstream networking potentials as these were characteristics of then stabile Southeast Asian societies (L. Andaya Reference Andaya2008; Gaynor Reference Gaynor2013). Adaptive cultural networking most often resulted from Southeast Asia's prominent intermediary position in the oceanic trade routes, as these ongoing contacts provided the double potential for cultural interactions between locals and the variety of international sojourners, and access to the assorted foreign goods, services, and ideas they provided (Hall Reference Hall2013). There were alternative opportunities for overland communication, as for example the longstanding networking and transit of populations and commodities across the south China borderlands into what is today Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam that included the exchanges of horses, elephants, cowrie shells, silver bullion and coinage, and Buddhist theology and other knowledge exchanges (Heng Reference Heng2006; Yang Reference Yang2004, Reference Yang2011; Sen Reference Sen2014).

Marginalization of Southeast Asia's multi-dimensional engagements in the eastern Indian Ocean region is in part the product of a view initially argued and then retracted by the Southeast Asia historian O. W. Wolters in the late 1960s (Wolters Reference Wolters1967, Reference Wolters1970, Reference Wolters1982), that the entry and residency of foreign merchants in the early Southeast Asian region was cyclical and tied to the opening and closing of China's ports, or responded to unstable political and societal factors on the western and eastern ends of the international maritime route (Wolters Reference Wolters1979; Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1989; Gunder Frank Reference Gunder Frank1998). Such a view assumed that the maritime route depended on the marketplaces at the route's ends in China, South Asia, and the Middle East, as these primary civilizations offered sufficient commercial potential and cultural opportunities to encourage trade in their networked secondary societies. In the reverse, if the primary marketplaces in the Middle East, South Asia, or China closed or were not accessible due to some local crisis, then international traders had less incentive to make the maritime passage, or alternatively settle in Southeast Asia's prosperous port regions. Regions that lay between China and South Asia suffered through periodic commercial downfalls accordingly, and resulting economic recessions initiated the fall of existing regional polities that overly depended on trade-engendered revenues. Sequentially new or recovering Middle East, South Asia, or China-based polities offered stable markets for the renewal and expansion of assorted Eastern Indian Ocean exchanges.

One objection to this overview of the prevailing patterns of exchange as end-products of China or India-linked engagements in the Southeast Asia regions is that it reinforces an emphasis on the external as the motor for change in the Southeast Asia region, and fails to recognize localizations in the development of marketplaces and civilizations within the region that lay not at the ends and middle of the route but along the route's entirety, and local capacity to become culturally creative as well as major consumers of the variety of Indian Ocean products on their own. One may alternatively argue, as for example in the cases of the Bay of Bengal, South China Sea, Java Sea, and linked eastern Indonesian archipelago regional networks connected to the major east-west maritime route, that once set in motion the various Southeast Asia centers of trade and their adjacent civilizations became so trade-centered that they could sustain an international route even without the participation of major consumer markets on their eastern or western oceanic ends (Ptak Reference Ptak1992, Reference Ptak1993, Reference Ptak1998a, Reference Ptak and Guillot1998b; Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam, Prakash and Lombard1999; Wisseman Christie Reference Wisseman Christie and Ray1999; Kulke Reference Kulke, Prakash and Lombard1999).

Scholars have assumed that merchants flocked to the Indian Ocean route in good times, because a market upswing increased their likelihood of profit (Abu Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1989). That is, traders would risk the uncertain voyages because they seemed assured of a significant material return for their initiatives and efforts. However, there was equal possibility that traders’ willingness to venture overseas was induced by a depressed market or unstable circumstances in their homeland, and that their entrepreneurial initiatives were the consequence of the practical necessity of seeking a living elsewhere. Southeast Asia's developing civilizations and their marketplaces certainly offered an attractive alternative (Hall Reference Hall2001; Wheeler Reference Wheeler, Thwin and Hall2011). Even the old view that there was a vital dependency on the ebb and flow in the volume of trade at China's and Middle East ports that resulted from dynastic transitions and changing government attitudes toward trade and traders has been challenged. Historians who specialize in China's history now question whether there were really significant periodic declines in China's trade volume, and assert that actual practice was quite different from the rhetoric in the official state documents (Kayoko, Shiro, and Reid Reference Kayoko, Shiro and Reid2013).

The increasing presence of foreign merchants and others in Southeast Asia, while in part the consequence of an expansive international marketplace, must also be considered as potentially resulting from economic or political failures in their homelands. For example, in the era of the Mongol conquests numerous regional populations responded by moving to more secure settings. Thus, numerous professionals from the Persian realms of modern-day Iran took residency in South Asia and the regions beyond during the thirteenth century, as Persia-based merchants had relocated or converted to Islam when the Persian Empire fell to Muslim armies in the seventh century (Sims-Williams Reference Sims-Williams, Cadonna and Lanciotti1994; Sen Reference Sen2003). Similarly, following the collapse of the Gupta realm in north India during the late sixth century, and again after the surrender of northern India to Muslim warriors in the eleventh century, numerous Hindu and Buddhist clerics found alternative employment in the service of south India's kings and in Southeast Asia's courts (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2003, Reference Lieberman2011; Asher and Talbot Reference Asher and Talbot2006). Clerical ‘knowledge agents’ of Islam in Southeast Asia included Java's mystically/spiritually endowed wali sanga [saints] and increasing numbers of sojourners with Middle Eastern roots who sought alternative residencies coincidental to the 1258 fall of the Abbasid dynasty in the Middle East and periodic insecurities during the era of the Delhi Sultanate in twelfth through sixteenth century northern India (Lambourn Reference Lambourn2008; Wade Reference Wade, Morgan and Reid2010).

Migrations of Chinese merchants into Southeast Asia were initially encouraged by Chinese officials in the Song era to secure more product volume from the regions to the south for domestic consumption as well as to enhance the China state's tax revenues, as the Song relaxed their previous travel restrictions on the Chinese merchant community. When the existing overseas-based traders network was not supplying sufficient commodity volume at the Chinese ports, China's port agents modified prior restrictions in dispatching Chinese merchant diaspora as a means to acquire additional tariff revenues, and to supply the Chinese aristocracy with the foreign commodities that were necessary in their ritual performances and conspicuous public displays (Shiro Reference Shiro1998; Sen Reference Sen2003; Shiro and Takashi Reference Shiro, Takashi and Kayoko2013; Chin Reference Chin, Kayoko, Shiro and Reid2013). Equally, sojourning was a means by which southern Chinese sought income that could sustain themselves and their families in desperate times whether economically, politically, or culturally challenging, as migration to the South was a logical and viable option (Chang Reference Chang, Ptak and Rothermund1991). Thus the greatest eras of Chinese migration into Southeast Asia and the establishment of Chinese diaspora communities in regional downstreams corresponded to the bad times and public disorders associated with declining or failed dynasties, as for example the fall of the Song (1279) and the rise of the Yuan (1271), or the fall of the Yuan and the rise of the Ming (1368) (Clark Reference Clark1991; Ptak Reference Ptak and Guillot1998a; Sen Reference Sen2003; So Reference So1998, Reference So2000; Whitmore Reference Whitmore2014).

Southeast Asia's acceptance as a strategic international trade intermediary as also a product source implies the periodic residence of traders and seagoing groups, who had to make stopovers waiting for a shift in the wind patterns that would allow them to return to their home ports. By at least the eleventh century sailors and traders rarely made the entire East-West passage, but only specialized in one portion of the route, and transferred their goods to and interacted with merchants and sojourners from other sectors of the passageway at a Southeast Asia regional port-polity. Southeast Asia's regional port-polity populations were thus in a constant state of flux, based on the wind patterns favorable to oceanic transit as well as the local market's potential as a source of international goods and/or local products.

One temporary resident population might replace another when ships arrived from an adjacent segment of the international passage (for example, from the South Asia coastline to Southeast Asia ports or from China to Southeast Asia ports) after the transitory residents embarked with the prior season's monsoon winds. Thus, historians have been reluctant to identify early Southeast Asian port-polities as legitimate cities, on the grounds that they might only have a large seasonally resident population dictated by monsoon wind patterns, but were the continuous homes of only a small number of year-round occupants (Wheatley Reference Wheatley1983; Wisseman-Christie Reference Wisseman Christie and Glover1992; Heng Reference Heng2009; Miksic Reference Miksic2013). And even these ‘permanent’ residents might make frequent passages between their port-polity downstream and its domestic upstream and linked coastal hinterlands. There sojourners who were wholesalers or petty traders exchanged their homeport's products for domestic commodities and manufactures in well-developed and hierarchical indigenous marketing systems (Bronson Reference Bronson and Glover1992; Wisseman Christie Reference Wisseman Christie and Ray1999; Hall Reference Hall2013).

As noted, the Southeast Asia region was widely regarded as an important commercial exchange nexus for commodities from China and the West, as well as its own spices, exotic jungle products (e.g., rhinoceros horn – a desired aphrodisiac, sandalwood, and tropical birds), and metals (variously tin, silver, and gold). However, to focus exclusively on the international trade ignores the developing hinterland market networks that supplied these products to the ports, as well as the indigenous demand for imported commodities – notably iron (as segments of the Southeast Asia region had an inadequate iron supply), and textiles (especially Indian cottons produced in the Gujarat region of upper west coast India and in the multiple weaving centers of India's east coast). Ceramics, and, in the time of the early Islamic conversions, tombstones were imported from Gujarat and south China (Lambourn Reference Lambourn2003, Reference Lambourn2008; Hall Reference Hall and Varadarajan2012). The Southeast Asia marketplace was important enough that Indian textiles were manufactured to Southeast Asia-resident specifications, as for example the long pieces of ritual cloth that Gujarat weavers produced to the specifications (size and design) of the Toraja society of the eastern Indonesian archipelago (Wisseman Christie Reference Wisseman Christie1993; Hall Reference Hall1996; Barnes and Kahlenberg Reference Barnes and Kahlenberg2010). Java's marketplace was sustained by a realm-wide monetary system based in the use of Chinese coinage that was in place by the thirteenth century, and consequently commodity value was most often determined in monetary terms rather than in reference to bulk. (Aelst Reference Aelst1995; Wisseman Christie Reference Wisseman Christie1996; Hall Reference Hall and Gommans2010).

Trade and Traders in the Early Eastern Indian Ocean Maritime Region

What, then, were the characteristics of the trade and traders who participated in the Southeast Asian portion of the early international maritime route? Because of their varying transitory regional stopovers the maritime traders may be thought of as members of fluid communities in motion, who individually or collectively re-conceptualize themselves relative to what and who they represented in ever-changing circumstances. Those who became local residents, if only for a short time, had to make the best of the circumstances in a setting in which there was an ongoing process of creativity and negotiation of identity (Ellen Reference Ellen2003; Hall Reference Hall2011, Reference Hall2013).

Membership in Southeast Asia's coastal communities was open to those who would risk the voyages and hardships of living in a foreign environment with limited cultural amenities. International seafarers had to accept their place in or among communities that consisted of their fellow transients and resident commercial specialists, or combinations of commercial specialists and other local residents. Community membership could be assigned by the itinerant merchants themselves, resident merchants, indigenous elite, or by mixtures thereof. Membership could be determined by internal or external factors, or both (Manguin Reference Manguin1993, Reference Manguin2002; Heng Reference Heng2008).

One can speak of multiple “fields of representation” associated with merchant communities, wherein early Southeast Asian merchants moved through cores and zones from which they derived their identities (Hall Reference Hall2013: 222–231). In the early Southeast Asian epigraphic sources merchants were not usually identified by their specific port of origin as is more typical of the post-1500 chronicle literature, but by their association with a regional core. A core might be the principle source of a major commodity, for example an entrepôt or region where certain products were available: tea (China), frankincense (Srivijaya), camphor (Barus), cloth (Kelinga), pepper (Samudra-Pasai, Banjarmasin), and spices (Java) imparted an associated identity. However, the Kelinga, Cham, and Khmer categorical generalizations in Java inscriptions and regional chronicle texts also imply an associated ethnicity. Chinese dynastic records provide recognition of the different ethnicities who were members of tribute delegations that arrived at the Chinese court. Among the most prominently mentioned were the intermediary Keling Muslim merchants based in southeast India who were also linked to Middle East ports-of-trade (Sen Reference Sen2003; Heng Reference Heng2009; Miksic Reference Miksic2013). Zonal identification derived from a merchant's travels within a specific sector of the trade route that were in part dictated by the seasonal monsoon winds, for example the Bay of Bengal, South China Sea, and Java Sea networks (Ptak Reference Ptak1992, Reference Ptak1998; Frasch Reference Frasch, Guillot, Lombard and Ptak1998; Subrahmanyan Reference Subrahmanyam, Prakash and Lombard1999; Hall Reference Hall2011). Merchants acquired local products within these networks that they would take elsewhere; in exchange they left their own trade commodities (e.g., textiles, ceramics, and/or spices) that were adopted and adapted into local communities, as potentially the merchants were themselves (Heng Reference Heng2006). A surviving fourteenth century Sumatra upstream Malay language legal text includes references to imported spices and other commodities that derived from local networking with downstream traders, as these international items had recorded value in the itemized Sumatra upstream code that favored commodity rather than monetary exchange (Miksic Reference Miksic2009; Kozok, et al. Reference Kozok, Hunter, Mahdi and Miksic2015). According to the Chinese dynastic records, Southeast Asia-based merchants traded as the representative agents of specific ports and served as members of these ports’ trade and tributary delegations, and therein the Chinese records ascribed their community membership. For example, Muslim traders, who may or may not have had a Middle East origin, were regularly accounted as participants in the Southeast Asia tributary missions to the Chinese court from the eleventh century (Sen Reference Sen2003; Heng Reference Heng2008). The frequent presence of Muslim traders among the embassy delegations was noteworthy enough to have warranted distinctive Chinese recognition, with the implication that these diaspora in some way assured the quality of trade and the types and value of goods an alien port provided to China's marketplace (Wade Reference Wade and Kayoko2013; Sen Reference Sen2014) (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Networked Indian Ocean maritime diaspora linkages. (Kenneth Hall)

Diaspora traders could become locally prominent. The earliest Southeast Asia example is a seventh century southern Vietnam inscription that records the Kaundinya myth commonly shared among early mainland Southeast Asian societies, wherein a South Asian sojourner married a local princess and therein initiated local kingship (Vickery Reference Vickery2003). Among later examples is the legend of the early sixteenth century northeast coast Java Demak ruler who, after making strategic stops in major networked ports-of-trade on the Sumatra and Java coastlines ultimately married an east Java Majapahit court princess, thus symbolizing his prominent northwest Java port's legitimacy as the heir to the previously dominant upstream-based court (Hall Reference Hall2014a). There is also the Thai record of a member of a Chinese merchant diaspora household who eventually became the ruler of the regionally powerful Ayutthaya realm. According to the Thai chronicles:

“The [previous] king passed away and no member of the royal family could be found to succeed him. So all the people praised Prince U Thong, who was the son of the leader of the Chinese merchant community [who was well-connected to two powerful Thai clan networks in the upstream Suphanburi and Lopburi regions], to be anointed as king to govern the kingdom [in due course he strategically resettled his upstream and downstream supporters in and around his new intermediate downstream Ayutthaya capital city in 1351]” (Gilman d' Arcy Paul Reference Gilman d'Arcy Paul1967: 37).

Port-polity authorities were expected to protect all involved in exchanges from undo exploitation, to insure that trade was transacted according to a commonly established and accepted standard of conduct and even a common code of law, as demonstrated in the fourteenth century compilation of the Melaka Maritime Laws (Winstedt and Jong Reference Winstedt and De Jong1956). Melaka's rulers reasoned that local prosperity was due to retention of locally based and seasonal sojourning diaspora traders, and thus sponsored a legal declaration favorable to Melaka's multi-ethnic marketplace participants. By doing so, Melaka's monarchs allowed its multi-ethnic trade community some latitude rather than severely restricting their variety of activities, but regularly confined them to their port residency or anchorage, thereby limiting their access to regional upstreams (Heng Reference Heng2009; Miksic Reference Miksic2013).

There were ‘circles of rivalry’ in the eastern Indian Ocean trade network: between merchants and locals and among the sojourners themselves. Rulers and other locally powerful persons – landholding elders, empowering priests, or governmental elites – frequently viewed the actions of ‘outsider’ merchants as threats to their reciprocity-based local networks (Hall Reference Hall2010). This is demonstrated in the restrictions placed on merchants and other local and foreign professionals by early Java monarchs, who limited the number of merchant/professionals who were allowed to become local residents (Wisseman Christie Reference Wisseman Christie1998). Contemporary Cham inscriptions recovered from the Vietnam coastline report the purposeful isolation of sojourning traders in coastal enclaves on the society's periphery (Hall Reference Hall2011; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Griffiths, Hardy and Wade2017a, Reference Whitmore, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017b). But merchants and other foreigners were regularly recruited into the regional political systems due to their status as ‘outsider’ non-integrated members of local society, frequently as a monarch's tax collectors (Hall Reference Hall2013).

Competition among the merchant communities themselves is demonstrated in the recurrent references to the raiding of rival ports-of-trade, as for example early southeast Sumatra-based Srivijaya's aggression against contending north Java and Melaka Straits regional ports and subsequent south Indian Chola maritime raids on Srivijaya's ports in 1025. The Chola maritime raids against Srivijaya's networked ports are reported in Chola inscriptions as well as in Chinese dynastic records, as are contemporary Chola maritime aggressions against regional Bay of Bengal ports-of-trade. These were likely related to contemporary Chola interests in having some degree of profitable return from the Bay of Bengal, Straits of Melaka, and South China Sea trade route in support of south India-based merchants. That a Chola-sponsored Hindu temple at Quanzhou modeled on the Meenakshi temple at Madurai was said to have been financed by Chola rulers in partnership with full- or part-time resident south India diaspora merchants points to these kinds of long-distance relationships (Guy Reference Guy and Schottenhammer2001; Kulke, Kesavapany, and Sukhuja, eds. Reference Kulke, Kesavapany and Sakhuja2009; Hall Reference Hall2014b).

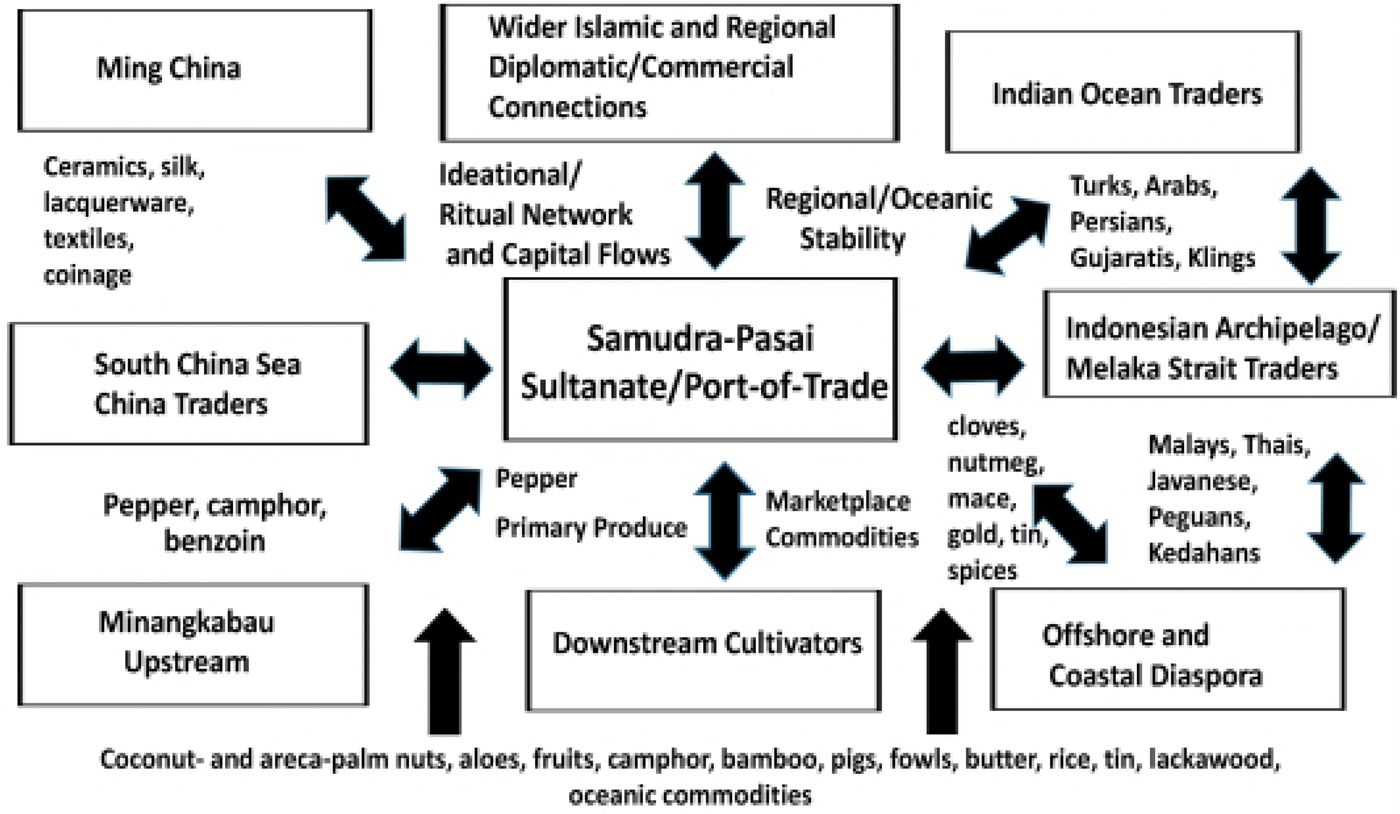

Thai and Java-based raiders were common in the Straits of Melaka region in the fourteenth century; similarly Cham courts had an interest in southern Vietnam staged raids against their western Khmer and northern Vietnamese neighbors in the eleventh through fifteenth centuries (Heng Reference Heng2009; Miksic Reference Miksic2013; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Griffiths, Hardy and Wade2017a, Reference Whitmore, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017b). Pre-1500 Straits of Melaka chronicle literature, including the Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai of the fourteenth-fifteenth century northeast Sumatra port-polity, record periodic raiding against ports-of-trade on the Sumatra and Straits of Melaka coastline (Hall Reference Hall2017). These raids have too frequently been characterized as political competition, attempts to acquire dependent labor, or to acquire plunder. In an alternative view, regional political ambitions were increasingly related to a court's commitment to support and consolidate a regional trading network rather than periodically pillaging its competitors (Hall Reference Hall2011). For example, the northeast Sumatra Samudra-Pasai port was initially known as a pepper marketplace, but eventually consolidated its control of northwest Sumatra Barus’ camphor and benzoin. Prior to Melaka's rise to prominence it was the Straits' premier marketplace with regular access to eastern Indonesian archipelago nutmeg, cloves, mace, and other spices (Hall Reference Hall2001; Miksic Reference Miksic2013).

Raids on a competing port or region did secure valuable plunder and manpower, but also desecrated one's rival(s), and in various ways discouraged competitive trade at a rival's port(s) or superseded their competition in the regional and international trade network (Manguin Reference Manguin2002; Reid Reference Reid2000). The following graphic (Fig. 4) depicts the complexity and multiple transactions centered in the c. 1200–1500 northeast Sumatra Samudra-Pasai port-polity as detailed in its contemporary court-chronicle and confirmed in the accounts of visiting sojourners, among these Ibn Battuta in 1346 (Gibb Reference Gibb1957; Hall Reference Hall2001, Reference Hall2017),

Figure 4. Networking and commodity flows of the c. 1200–1500 Samudra-Pasai port-polity as identified in the Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai. (Kenneth Hall)

These maritime competitions included merchant communities and/or drew upon their resources, minimally as the source of ships and provisions, as well as seafaring warriors. In an early Srivijaya inscription a ship-owner was the acknowledged source of vessels for the Srivijaya monarch's expeditions against his rivals (Manguin Reference Manguin2016). Fifteenth century Java port-polities were planning a raid on Melaka even before Portuguese conquest in 1511, and a regional alliance subsequently attacked Portuguese Melaka in an attempt to displace Portuguese control of the strategic port, intending to divert its monopolistic trade to other regional port-polities (Manguin Reference Manguin1991). With the fall of Melaka in 1511, numbers of maritime diaspora relocated to Demak on Java's northeast coast, Banjarmasin in southeast Borneo, Aceh in north Sumatra, and Thai Ayutthaya to the north (Hall Reference Hall2014a).

It is unrealistic and improbable to assume that there was a generalized brotherhood among the merchants, although merchants periodically shared a common place of residence, and also religion. One needs to be careful not to envision clear-cut dichotomies at work when discussing these early merchant communities, as for example the still too frequent mistaken generalization that all Muslim traders were Middle East-based ‘Arabs’ (Ray Reference Ray1994; Sen Reference Sen2003), as similarly that all Chinese and South Asians were inclusively ‘Chinese’ and ‘Indians’ (Chang Reference Chang, Ptak and Rothermund1991; Ptak Reference Ptak1998; Salmon Reference Salmon2002). Another notable misrepresentation is the bipolar distinction between sedentary merchants (i.e., those assumed to be residential) and others who were locally mobile (i.e., transient). Clearly, due to the seasonal shifting winds of the monsoons, Indian Ocean sojourning merchants were sometimes primarily mobile and othertimes sedentary. However often those from a maritime diaspora who were based in a specific port and did not make the seasonal oceanic voyages were also locally mobile, as for example when they traveled inland/upstream to market or to gather products, or as they regularly took short trips to a series of networked regional ports-of-trade (Kathirithamby-Wells and Villiers Reference Kathirithamby-Wells and Villiers1990; Gaynor Reference Gaynor2013). Maps of fifteenth century Melaka demonstrate clustered residencies of Chinese, South Asian, Middle Eastern, and other maritime diaspora, as this was similarly the pattern in other prominent fifteenth century Southeast Asia ports (Map 3).

Map 3: The Melaka urban core ‘Activity Zone’ c. 1500. (Kenneth Hall)

In maritime Southeast Asia there has always been an itinerant community of upstream and downstream and coastal-networking seafarers who, based out of a home port, acted as the vital intermediaries between major ports-of-trade and communities in the adjacent river mouths and their upstreams. Downstream based vessels of assorted sizes gathered and relocated products, as the residents of a port-of-trade network in a variety of ways acted as intermediaries in both the international and indigenous marketplaces (Tan Reference Tan2012). Where do these intermediary sojourners fit in the overall configuration of early Southeast Asian trade communities, and what was the nature of and the consequence of these merchants’ local networking relative to international trade and traders? Recent studies of the Bugis and other sojourning maritime community networks within Southeast Asia's eastern archipelago provide clues, and even conclude that post-1500 eastern archipelago itinerant communities became the basis of their own networked ‘cultural state’ (L. Andaya Reference Andaya1993; Ellen Reference Ellen2003; Gaynor 2016).

In addressing the character of the port communities populated by a mix of international sojourners, who were forced to lay over until the next monsoon season as these contrasted to ‘continuous’ residents, we know that itinerant Chinese merchant diaspora frequently married and had a network of wives and families resident among the ports in which they did business, as in the previously cited example. Wives and families looked after their extended family's interests when Chinese merchant sojourners traveled to other ports (Chang Reference Chang, Ptak and Rothermund1991; Manguin Reference Manguin1991; Reid Reference Reid1996). That non-Chinese merchants were also likely to intermarry and establish some form of continuing community membership is demonstrated in the contemporary records of the sojourning Hadrami and ‘Persian’ merchant communities (Ho Reference Ho2006). Hadrami merchants were resident in most of the major ports-of-trade between Yemen and Melaka by 1500, where their local presence was balanced by their responsibilities and continued interactions with their international network in which ports on the Gujarat and the Malabar coastline on India's west coast assumed particular importance. So-called ‘Persian’ merchants who were based in Masulipatnam and other upper Bay of Bengal regional ports by the fifteenth century also had ongoing connections to the Iranian region. This ‘Persian’ merchant community dates to the earliest centuries of the first millennium, when Chinese diplomats who traveled between China and India repeatedly referenced resident and itinerant Sogdian merchants then active in Southeast Asia's ports-of-trade (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam, Prakash and Lombard1999; Sen Reference Sen2003). Networking from a common point of origin was also characteristic of other merchant diaspora, as the Cairo Geniza records document Egyptian Fustat-connected Indian Ocean Jewish merchants from the eleventh century (Gil Reference Gil2003), as was also the case among the Tamil Hindu and Muslim (e.g., Keling) merchant communities discussed above, whose inscriptions and fifteenth century Sejarah Melayu court chronicle records reflect their continuing networked loyalty to their south Indian homeland, as was also acknowledged in contemporary Chinese and Southeast Asian documentation (Hall Reference Hall and Gommans2010).

Some historians have argued that Southeast Asia's Islamic conversions were not primarily spiritually motivated but trade-related, to induce specific foreign traders to do business in new Islamic ports with resulting increases in local revenue collections by regional monarchs who were co-religionists (Hall Reference Hall2001, Reference Hall2014a). While at this distance in time it is impossible to know why widespread Islamic conversion took place, and there is no reason to doubt the general sincerity of those who did so, there were certainly positive implications consequent to conversion in the reality of economic benefits that derived from the conversions of local rulers and traders. In this view Southeast Asia rulers sought to attract Muslim traders, who were by the thirteenth century preeminent on the international route between the Middle East and China, and induced these seafarers to make their monsoon layovers in Muslim ports rather than others. Local conversions implied a favorable religious environment and the assurance of the local acceptance of the Islamic moral code, at least as this applied to commercial if not personal transactions.

Notably, coastal port-polity elites were among the first converts to Islam, and only later did their adjacent upstream hinterland populations join them. The hinterland populations seemingly had little initial incentive to accept Islam, since their community membership was already satisfied by traditional non-Islamic standards of interaction. Eventually upstream conversions to Islam took place through the agency of downstream rulers, who encouraged local acceptance of Islam as a means to legitimize their own local authority, and also to increase the flow of hinterland produce to downstream ports (Hall Reference Hall2016). Thus, this local patronage of Islamic merchants and local conversions to Islam may have initially been only token gestures meant to derive economic benefits; the conversion equally could draw on Islam's political potential to link diverse upstream and downstream population clusters into a common cultural community, or in a more positive light, conversion resulted in a political elite's genuine spiritual commitment that could sustain more practical and mundane societal goals (Hall Reference Hall2001; Wade Reference Wade, Morgan and Reid2010).

Generally historians have been reluctant to see merchant sojourners as sources of cultural transmission, instead crediting priests, monks, and scholar ‘knowledge practioners’ who took passage alongside them (Morillo Reference Morillo and Hall2011). Merchant groups who associated with and patronized the Muslim, Buddhist, Indic, and Chinese cultural realms had connections that undoubtedly offered them opportunities for cultural brokering. Merchant and sailor ‘worldly travelers’ were not devoid of culture as their worldly travels made them culturally sensitive to the issues of inclusion rather than exclusion. Diaspora populations financed temples, retreats, and mosques to facilitate, promote, and substantiate their role as members in a ritual community – with focus on their pursuit of societal well-being as rightful and contributing members of a society rather than being obsessed with achieving their personal gain at the expense of others (Kulke Reference Kulke1993; Lambourn Reference Lambourn and Hall2011). It was important that c. 1400 merchants focused on Indic, Muslim, or Chinese contributions to world order as the source of their own legitimacy and a sense of place, to neutralize local characterizations as ‘outsiders’ that were not complementary, and to mobilize against likely and personal threats to their well-being (Hall Reference Hall2011; Morillo Reference Morillo and Hall2011; Lambourn Reference Lambourn and Hall2011; Whitmore Reference Whitmore and Hall2011). The potentials of international knowledge transfers are depicted in the graphic above (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Knowledge networking in pre-1500 Southeast Asia. (Kenneth Hall)

Contested Agencies in the Fifteenth Century Straits of Melaka Region

Based on the cited Southeast Asia evidence, revisionists assert that from the late thirteenth through early fifteenth century (in the eras of late Yuan and early Ming sovereignty) enhanced Chinese diplomatic agencies in the Southeast Asia region were less about confirming Chinese regional sovereignty over the maritime passageway, and more about soliciting tributary trade that would supply China's marketplace demand for Indian Ocean products, and therein increase the volume of taxable international trade taking place in China's ports. Thus, Yuan and Ming court regional outreach initiatives were less reactive to a generalized decline of China's maritime trade, or due to China's expansionist dynastic ambitions, but resulted from dynastic concern that China was being relegated to the periphery of the Indian Ocean maritime world. Therein Yuan and early Ming monarchs supported diplomatic attempts to recover some of the lost trade volume that was going to China's Indian Ocean market competition. Before the Ming restricted exports, most notably Chinese ceramics from the 1430s until roughly 1570, during what historians have called the ‘Ming gap’, China's agents promoted exports (especially ceramics) and welcomed reciprocal foreign trade and embassy delegations, to not only guarantee China's access to the best international products (e.g., spices, regional specialties, and a variety of forest products), but secondarily to reassert China's political interests in the Indian Ocean region, most notably in maintaining the fluidity of the East-West maritime passageway (Brown Reference Brown2008; Laichen Reference Laichen and Kayoko2013).

In the fifteenth century Melaka rose and provided a singular prominent intermediary marketplace at the intersection of the Bay of Bengal, South China Sea, and Java Sea regional networks. Ming rulers supported the founding of Melaka, and the voyages of the Ming eunuch Admiral Zheng He reflect their attempt to assert and revitalize the Tang-era China-centered tributary trade system (Chang Reference Chang, Ptak and Rothermund1991; Wade Reference Wade2005). However, Ming initiatives ultimately failed, not just because of debate within China itself relative to the appropriateness of China's external initiatives (Wade Reference Wade2015), but because the old tributary system was no longer valid. Despite what many historians have proposed, China could no longer ‘rule the seas’, even though they still could send out fleets that included one thousand ton junks. Revisionist historians now depict Ming maritime ventures as attempts to reassert an idealized dynastic past in much the same way that previous Chinese dynasties had repeatedly tried to conquer what they assumed to be the ‘natural’ regions of Chinese authority, as notably reflected in the repeated and failed attempts of new Chinese dynasties to reassert China's ‘rightful’ authority over Vietnam from the eleventh century on (Whitmore Reference Wisseman Christie1996; Cooke, Tana, and Anderson Reference Cooke, Tana and Anderson2013). Instead, Melaka's rise to prominence by the fifteenth century depended on the complexity of the multi-centered trade in the Indian Ocean, and the practicality of establishing a single Southeast Asia clearinghouse for East-West Indian Ocean trade in partnership with China in that era. In essence, it was appropriate that this central entrepôt was in Southeast Asia, because Southeast Asia was geographically the pivotal marketing center of Indian Ocean trade and the strategic source of the most in demand Indian Ocean commodities, notably textiles, ceramics, spices, and metals.

While the remaining records tell us little about the men who traded from fifteenth century Melaka, we know a good deal about its leaders. From the beginning they took great care to make their new port attractive to international traders. As among its predecessors, Melaka's residency patterns ebbed and flowed with the monsoons. Traders and other groups maintained permanent warehouse and residency compounds, the forerunners to the European ‘factories’ that were later established at strategic Indian Ocean ports. However, except for a few year-round representatives of the major trading communities, Melaka's population in these compounds was seasonal. A special governing body and judicial system gave visiting merchants and their goods protection while in the port. The main court officials, the Bendahara [prime minister], Laksamana [admiral of the monarch's fleet], Syahbandar [harbor master], and Temenggung [minister of justice, defense, and palace affairs] all facilitated trade in various ways. Melaka's port regulations aided the local exchange of goods so merchants did not find themselves overly burdened. This way they did not stay so long in port that they lost a favorable monsoon wind for their return voyage. There were also regular standardized customs duties as well as fixed weights and measures and units of coinage that helped support marketplace exchanges and generalized stability (Thomaz Reference Thomaz and Reid1993; Kozok Reference Kozok, Hunter, Mahdi and Miksic2015).

Melaka's Malay nobles did not take part in the affairs of the marketplace. They delegated this to the merchants themselves, but they did command the fleet of ships that policed the Straits to keep it free from piracy. In addition, vessels powered by oar rather than sail also patrolled the Straits, so that they could tow becalmed ships into port. Melaka's success enticed regional chiefs, who entered the traditional Straits’ alliance networking among rulers and ruled (Milner Reference Milner1982). Under this agreement, the Melaka monarch made periodic redistributions of wealth to those who remained subordinate to his port-polity, and omitted those who conducted acts of piracy or allied with Melaka's competitors.

The initiatives of Melaka's early rulers laid the foundation for Melaka's international prominence. Heavy naval traffic came via the monsoons from both western and eastern Asia. India-based ships arrived regularly from India's southern coastline, Sri Lanka, and the wider Bay of Bengal coastline. Marketplace commodities included luxury items from the Middle East, such as rosewater, incense, opium, and carpets, as well as seeds and grains, but the bulk of the fifteenth century cargoes from the west were made up of cotton cloth from the Gujarat and Coromandel coasts (Hall Reference Hall and Varadarajan2012). Vessels from Bengal brought foodstuffs, rice, cane sugar, dried and salted meat and fish, preserved vegetables and candied fruits, as well as local white cloth fabrics that could be locally decorated. Malabar merchants from India's southwest coast brought pepper and Middle Eastern goods. The Bago (Pegu) polity in lower Myanmar (Burma) also supplied foodstuffs, rice and sugar, and ships. In return, spices, gold, camphor, tin, sandalwood, alum, and pearls were sent from Melaka, as well as re-exports from China that included porcelain, musk, silk, quicksilver, copper, and vermillion. Malabar and Sumatran pepper was carried to the Bengal coastline for regional distribution, as opium from Middle East was also a Bengal re-export (Meilink-Roelofsz Reference Meilink-Roelofsz1955; Wake Reference Wake1967; Miksic Reference Miksic2013).

Though China may have discouraged official tributary trade with the South after the 1430s, there was still an ample, unofficial and privately financed trade conducted by junks sailing from south China ports and intermediary ports on the south and central Vietnam coastline (Wade and Laichen Reference Wade and Laichen2010; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Dallapiccola and Verghese2017b). Prominent commodities included large quantities of raw and woven silks, damask, satin and brocade, porcelain and pottery, musk, camphor, and pearls, copper, iron, and copper and iron utensils, as well as the less valuable alum, saltpeter, and sulfur that were necessities for early regional gunpowder warfare. Regular shipping transfers also came from Thai Ayutthaya, Vietnam, Java, Borneo, and the Philippines, which contributed foodstuffs, jungle goods, ceramics, and a variety of other trade items (Laichen Reference Laichen2003, Reference Laichen, Tran and Reid2006, Reference Laichen, Thwin and Hall2011, Reference Laichen and Kayoko2013).

By the fifteenth century trade within the Southeast Asia archipelago had become highly profitable; the spices of the eastern Indonesian archipelago Moluccas – notably nutmeg, mace, and cloves – were in global demand. Intra-archipelago trade was at that time increasingly dominated by merchant-seafarers based in the transitional Muslim-ruled ports of Java's north coast, but mixed ethnic Eastern Archipelago sojourners, most notably those known as Bugis, were becoming a factor (L. Andaya Reference Andaya1993; Gaynor Reference Gaynor2013). By the end of the fifteenth century, when the first Portuguese missions reached Asia, Melaka remained the major commercial hub of Asian trade. Early arriving Portuguese, whose home ports in the Atlantic Ocean were poor and provincial by Melaka's cosmopolitan standards, were awed by what they saw, and left impressive accounts of the bustling Melaka and its networked connections.

In the words of the early fifteenth century Portuguese scribe Tome Pires, Southeast Asia was “at the end of the monsoon, where you find what you want, and sometimes more than you are looking for” (Cortesao Reference Cortesao1944: 228). When Europeans came to Southeast Asia in the early sixteenth century, they saw Melaka as more than a marketplace. It was a symbol of the wealth and luxury of Asia. They were eager to circumvent the monopoly of Venice on the priceless spice trade, and the great wealth and luxury available in this trade enticed them halfway around the world in their tiny, uncomfortable ships. Thus, when the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean in the early 1500s their objective was to seize Melaka, which they considered to be the then pivotal center of Asian trade. At the same time a fleet of ships based in north Java ports-of-trade were preparing a similar attack on Melaka, only to have the Portuguese do it first (Manguin Reference Manguin1993).

What the Portuguese did not understand was that Melaka was no more than an agreed upon marketplace intermediary for the commodities of other linked centers rather than an imperial authority. Thus, when the Portuguese seized Melaka many of the sedentary and migratory merchant communities responded by shifting their trade to other equally acceptable and mutually inter-changeable regional ports: Aceh, Johor, Java, Ayutthaya, Bago, Demak, Banjarmasin, and Hoi An among others. The inclusive Southeast Asia region remained prominent in sixteenth century Indian Ocean trade as a source of products, especially spices, and as an intermediary transit center strategically arbitrating exchange between Western and extended Eastern Indian Ocean maritime activity zones.

International merchants who entered partnerships with the leaders of newly emerging regional polities capitalized on the benefits of alliances among rulers and merchants as in the past but at increased volume (Reid Reference Reid1996; Lieberman Reference Lieberman1997, Reference Lieberman2003, Reference Lieberman2009). This was similar to the way contemporary up-and-coming Western European monarchies (e.g., Tudor England and The Netherlands) were in partnership with evolving East India joint stock companies. Perhaps the greatest sixteenth century transition was due to the widespread use of gunpowder warfare that became a factor in limited regional competition in the previous century, notably in warfare between Dai Viet and China (Laichen Reference Laichen, Tran and Reid2006), but in response to Portuguese militancy Southeast Asian polities began to arm themselves and in some cases shifted their trade to strategic sites that were better suited for gunpowder warfare defense. Despite increased European aggression that was focal for establishing a regional monopoly, long established patterns of multi-centered trade and commodity transfers prevailed as regional authorities rapidly countered with their own gunpowder weaponry and employed European and Asian diaspora mercenaries (Laichen Reference Laichen, Thwin and Hall2011, Reference Laichen and Kayoko2013). There was enhanced commercial maritime activity in the eastern Indonesian archipelago and Sulu Sea regions that had previously been peripheral to the mainline of Indian Ocean commerce.

In sum, the fluidity and continuity of ‘borderless’ maritime trade and cultural flows – most notably the regional embrace of Islam in insular Southeast Asia and variations of Theravada and Mahayana (Chan/Zen) Buddhism on the Southeast Asia mainland – that developed over the previous centuries was not significantly altered in the sixteenth century. Existing deeply rooted regional agencies were able to retain control of the major market forces and societal patterns that had long defined the extended eastern Indian Ocean region (Hall Reference Hall2014a). As reported, while Melaka fell to the Portuguese in 1511, this did not significantly alter the existing eastern Indian Ocean trading system, but instead provided the opportunity for additional marketplaces to profit from the overall region's variety of products as consequent to enhanced international consumer demand. In the next century the Dutch would attempt to dominate Straits of Melaka and eastern Indonesian archipelago trade (Clulow Reference Clulow2014), but like the Portuguese earlier, they ultimately failed as the deeply rooted and diffused ‘borderless’ multi-dimensional eastern Indian Ocean cultural and commercial networks prevailed (Reid Reference Reid2015).