Impact statement

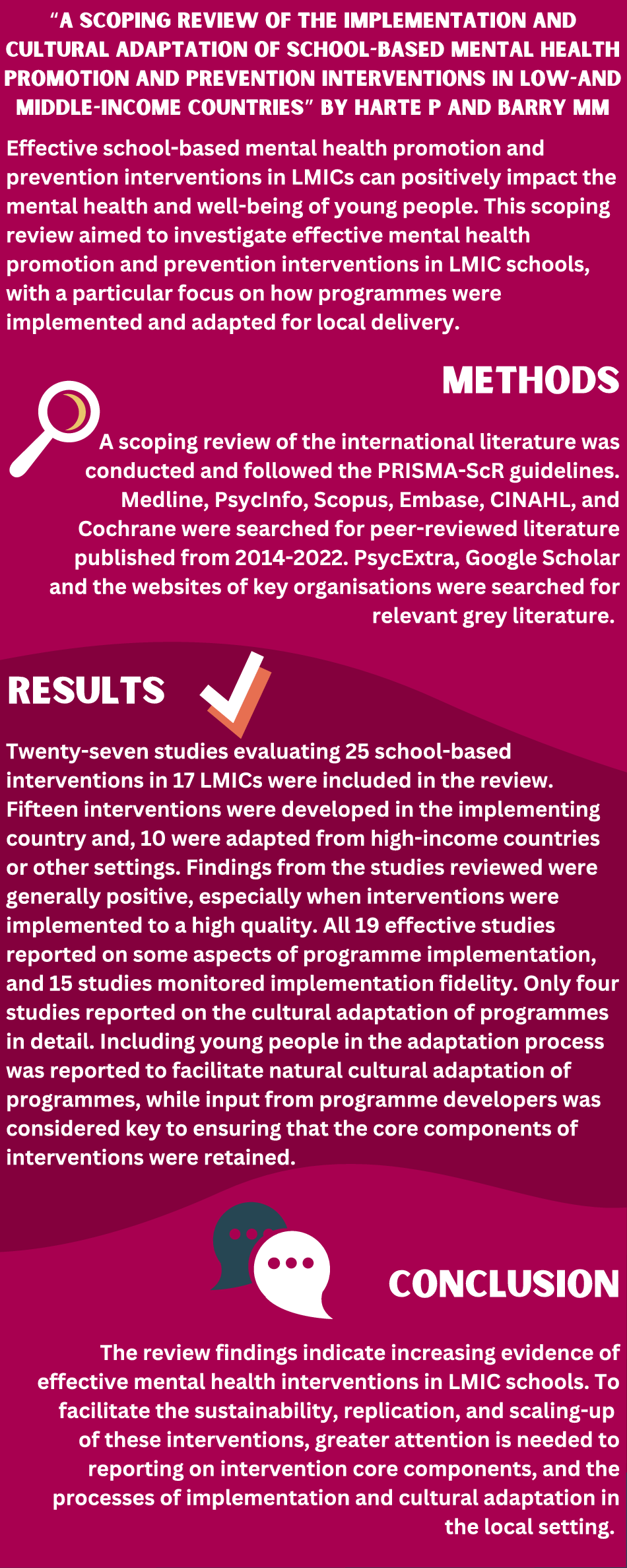

Effective school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) can positively impact the mental health and well-being of large numbers of young people. This scoping review sought to map the peer-reviewed and grey literature published from 2014 to 2022 on the process of implementing effective mental health promotion and prevention interventions in schools in LMICs. A total of 27 studies evaluating 25 school-based mental health interventions were identified. This review has a particular focus on how programmes were implemented and adapted for local delivery, thereby adding to the dearth of literature on implementation and the cultural adaptation of mental health interventions in LMICs. The increase in the number of studies reporting on implementation is encouraging, although reporting varied greatly between studies. Fifteen effective studies measured programme implementation, with quality of delivery being the most widely reported domain. The review findings endorse the importance of high-quality programme implementation to ensure positive outcomes. Findings also highlight the need to monitor and address barriers to implementation and to measure multiple domains of implementation, including the core dimensions; dosage, adherence, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness and programme differentiation. In addition, evidence-based interventions from HICs and other settings can be delivered effectively in LMIC schools when they are adapted to the local context. Cultural adaptation of interventions promotes participant responsiveness and the local acceptance of programmes. Reporting on the adaptation process facilitates the replication and scaling-up of interventions; however, only four of the reviewed studies reported on the cultural adaptation process in detail. The review findings highlight the need for a greater focus on supporting and reporting on the implementation process employed in under-resourced schools in LMICs, including the cultural adaptation of interventions using appropriate frameworks in a process involving young people and programme developers.

Introduction

Good mental health is a basic human right and an essential component of overall health and well-being (WHO, 2022). Positive mental health is a necessary resource for optimal quality of life and is fundamental to the development of safe communities and sustainable global development (UN, 2015). Poor mental health adversely impacts individuals, families, communities and the economy (Renwick et al., Reference Renwick, Pedley, Johnson, Bell, Lovell, Bee and Brooks2022; WHO, 2022). It is estimated that 13% of adolescents globally aged 10–19 years are living with a diagnosed mental disorder, with many more reporting sub-clinical psychosocial stress (UNICEF, 2021), and suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among males and females aged 15–29 years (WHO, 2022). Evidence points to the increased prevalence of mental ill-health among young people since the COVID-19 pandemic (UNICEF, 2021; WHO, 2022), particularly among those living in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) who face disproportionate levels of adversity (WHO, 2022). The explicit reference to mental health in the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 (UN 2015) and recent global reports focussing on the importance of promoting young people’s mental health (UNICEF, 2021; WHO, 2022) endorse the need for effective mental health promotion and prevention interventions for young people, particularly in LMICs where 90% of the world’s young people live (World-Bank, 2017).

Mental health is shaped by a complex interaction of individual, family, community and structural level factors (WHO, 2012), and childhood and adolescence represent particularly vulnerable periods in mental health development (UNICEF, 2021). Poor mental health during these developmental periods adversely affects positive development, social behaviours, educational outcomes and the health of future generations (Renwick et al., Reference Renwick, Pedley, Johnson, Bell, Lovell, Bee and Brooks2022). Mental health promotion and prevention interventions effectively implemented during childhood and adolescence, particularly in school settings, can positively impact mental health and well-being, and increase social and emotional skills and the academic performance of young people (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Oberle, Durlak and Weissberg2017; Aldridge and McChesney, Reference Aldridge and McChesney2018), including those who have been exposed to adverse experiences (Higgen et al., Reference Higgen, Mueller and Mösko2022).

Schools form a critical part of the socio-ecological system within which young people’s mental health develops and are therefore an important setting for mental health promotion (WHO, 2009, 2014; Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Petersen and Jenkins2019). Universal skill-based interventions (Skeen et al., Reference Skeen, Laurenzi, Gordon, Du Toit, Tomlinson, Dua, Fleischmann, Kohl, Ross, Servili, Brand, Dowdall, Lund, Van Der Westhuizen, Carvajal-Aguirre, De Carvalho and Melendez-Torres2019; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020; Chuecas et al., Reference Chuecas, Alfaro, Benavente and Ditzel2022) and social and emotional learning programmes (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Oberle, Durlak and Weissberg2017) in schools promote positive behaviours and relationships, improve mental health and can improve academic performance; while mental health literacy interventions can encourage help-seeking behaviours and decrease stigma among students and school staff (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Jorm and Wright2007; Yamaguchi et al., Reference Yamaguchi, Foo, Nishida, Ogawa, Togo and Sasaki2020). Additionally, since schools can be home to risk factors for poor mental health such as bullying and academic stress, school-based primary prevention programmes (universal, selective and indicated) can reduce the risk of mental ill-health (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Sharma, Irfan, Zaman, Vaivada and Bhutta2022). Evidence points to the positive impact and cost-effectiveness of whole-school universal interventions that follow the World Health Organisation (WHO) Health Promoting Schools Framework (WHO, 2021b) over curriculum-only programmes (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Barry, Chisolm, Gronholm, Egbe and Thornicroft2016; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020; WHO/UNICEF, 2021; Higgen et al., Reference Higgen, Mueller and Mösko2022); however, high-quality implementation is crucial to the effectiveness and sustainability of programmes (Durlak and DuPre, Reference Durlak and DuPre2008; Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011).

Implementation refers to the way in which programmes are delivered in real-life settings (Durlak, Reference Durlak, Humphrey, Lendrum, Wigelsworth and Greenberg2019) and is influenced by individual, community and macro-level factors (Domitrovich et al., Reference Domitrovich, Bradshaw, Poduska, Hoagwood, Buckley, Olin, Romanelli, Leaf, Greenberg and Ialongo2008). Monitoring and reporting on the five inter-related domains of implementation, including adherence, dosage, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness and programme differentiation (Dane and Schneider, Reference Dane and Schneider1998), is crucial to the fair interpretation of outcomes and replication of programmes (Dowling and Barry, Reference Dowling and Barry2020; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020). Exploring and addressing the barriers and facilitators to implementation is considered key to the sustainability and scaling-up of programmes outside of research conditions (Domitrovich et al., Reference Domitrovich, Bradshaw, Poduska, Hoagwood, Buckley, Olin, Romanelli, Leaf, Greenberg and Ialongo2008). Previous studies have outlined various moderators of effective implementation (Domitrovich et al., Reference Domitrovich, Bradshaw, Poduska, Hoagwood, Buckley, Olin, Romanelli, Leaf, Greenberg and Ialongo2008; Rojas-Andrade and Bahamondes, Reference Rojas-Andrade and Bahamondes2019). In low-resource schools in LMICs, barriers to effective implementation can compromise outcomes, including high pupil-teacher ratios (TISSA, 2014; McMullen and McMullen, Reference McMullen and McMullen2018) and insufficient resources and funding that necessitate adaptations to programmes, such as shortening programme durations or delivery by volunteers (Strohmeier and Spiel, Reference Strohmeier, Spiel and Smith2019). Research has also highlighted the importance of culturally adapting interventions to the local context and culture (Castro-Olivo, Reference Castro-Olivo2017; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021) using “a priori” frameworks (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Villarreal and Castro2017) to guide the process such as the ecological validity model (EVM) (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995) or Barrera and Castro’s (Reference Barrera and Castro2006) four-step heuristic framework. Adaptations made to programme language, content and concepts, in a process involving key stakeholders can increase participant responsiveness and programme acceptance (Castro-Villarreal and Rodriguez, Reference Castro-Villarreal and Rodriguez2017; Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Skinner, Alvarado, Kapungu, Reavley, Patton, Jessee, Plaut, Moss, Bennett, Sawyer, Sebany, Sexton, Olenik and Petroni2019).

A research gap exists in the context of school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions in LMICs as much of the available robust evidence is from HICs (Das et al., Reference Das, Salam, Arshad, Finkelstein and Bhutta2016; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Barry, Chisolm, Gronholm, Egbe and Thornicroft2016; Chuecas et al., Reference Chuecas, Alfaro, Benavente and Ditzel2022). Although recent literature suggests an increase in reporting on implementation in HICs (Dowling and Barry, Reference Dowling and Barry2020), few studies use quantifiable measures and/or report on all five domains of implementation (Hagermoser Sanetti and Fallon, Reference Hagermoser Sanetti and Fallon2011; Bruhn et al., Reference Bruhn, Hirsch and Lloyd2015; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020). Likewise, relatively few studies report specifically on how programmes from HICs and other settings can be culturally adapted for delivery in LMICs (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021). In addition, many existing evidence reviews focus primarily on studies employing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and robust quasi-experimental study designs and search only electronic academic databases. While RCTs are considered the gold standard in assessing the internal validity of programmes, a mixed methods approach to evaluation can better determine their external validity (McQueen, Reference McQueen2001). A grey literature search and the inclusion of all study designs is important in the context of research from LMICs, to allow for a more complete mapping of the evidence, especially with regard to the implementation process and cultural adaptation of interventions (Gimba et al., Reference Gimba, Harris, Saito, Udah, Martin and Wheeler2020; Chuecas et al., Reference Chuecas, Alfaro, Benavente and Ditzel2022).

This review, therefore, aimed to investigate the implementation process involved in delivering effective mental health promotion and prevention (universal, selective and indicated) interventions in school settings for children and adolescents in LMICs. The inclusion of all study designs and a grey literature search allowed for better exploration of the study objectives.

Specific study objectives include:

-

I. to investigate the primary outcomes of interventions on the mental health and well-being of participants and any secondary outcomes on physical health, knowledge, stigma and health behaviours;

-

II. to investigate the number of effective studies that provided details of implementation;

-

III. to examine the process of implementation of interventions;

-

IV. to identify any barriers or facilitators to the effective implementation of programmes;

-

V. to detail any cultural adaptations made to programmes from their original models.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature was conducted and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, MacDonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tuncalp and Straus2018). The process was guided by the Arksey & O’Malley five-stage framework (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005).

Eligibility criteria

Study selection criteria were developed in line with the population concept context (PCC) framework (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018), which informed the research question. Academic and grey literature in electronic form published from 2014 to 2022 was deemed eligible for inclusion if: (i) participants were boys/girls attending primary/secondary schools, (ii) interventions were school-based and aimed to promote positive mental health/prevent mental disorders of participants and (iii) interventions were implemented in LMICs as classified by the World Bank Criteria (World Bank, n.d.) at the time of the study (https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/).

All primary studies, including RCT, quasi-experimental, cohort and qualitative study designs, were eligible if they met the inclusion criteria. Primary outcomes of interest concerned the mental health and well-being of participants and any secondary outcomes on physical health, knowledge, stigma and health behaviours were noted. Studies evaluating interventions delivered in humanitarian settings and targeting young people with specific disabilities, for example, children with stuttering deficit, were excluded. Due to time constraints, they were considered special cases and beyond the scope of this review.

Search strategy

The electronic academic databases Medline, PsycInfo, Scopus, Embase, CINAHL and Cochrane were searched in May 2022 for relevant peer-reviewed articles. PyscExtra, Google Scholar and key websites (WHO and UNs International Children’s Emergency Fund [UNICEF]) were also searched for relevant grey literature. Search limiters included English language texts only, published between 2014 and 2022. This specific time frame was chosen to map the evidence since the publication of the WHO Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan in 2013 (WHO, 2021a). In addition, the reference lists of key studies were hand-searched to ensure no relevant studies were missed.

Two concept searches were conducted in each database. Individual search terms were combined with the Boolean Operator “OR” and concepts combined with “AND” (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for the search terms and concepts used across all databases and the specific search strategy used in CINAHL database, respectively).

Search 1: (population terms) AND (setting terms) AND (positive mental health terms) AND (programme terms) AND (context terms).

Search 2: (population terms) AND (setting terms) AND (negative mental health terms) AND (programme terms) AND (context terms).

Study selection

The search process yielded 19,746 studies. After deduplication, 9,537 studies remained and were exported to Rayyan software (Ouzzani et al., Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016), where further deduplication left 9,145 articles. Following screening of those titles and abstracts using the inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined, 104 articles remained for full-text review. A further 28 eligible studies were identified from website searches and by hand-searching key studies, leaving a total of 132 studies for full-text review. The final selection of studies for inclusion was based on a review by two researchers (PH and MMB). Twenty-seven studies that met the eligibility criteria were selected for data extraction (Figure 1 contains a PRISMA flow chart summarising the search and screening process).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

Data extraction

Studies were grouped according to the type and focus of the intervention. Data were then extracted, sorted and charted in tabular form in Microsoft Excel. The data extracted reflected the study aim and objectives. A narrative synthesis of results was then undertaken, which provided a commentary on the main findings.

Although critical appraisal of studies is not recommended in scoping reviews (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Marnie, Tricco, Pollock, Munn, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey and Khalil2020; Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Peters, Khalil, McInerney, Alexander, Tricco, Evans, de Moraes, Godfrey, Pieper, Saran, Stern and Munn2023), quality appraisal was carried out to give more depth to the discussion and was guided by Joanna Briggs Institute checklists (JBI, 2020), available at https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Checklists were selected as appropriate for the type of study design under review and studies were rated strong, moderate, or weak.

Results

Based on the review process, 27 studies evaluating 25 school-based mental health promotion and primary prevention interventions in 17 LMICs were identified (see Tables 1–3). Study designs included RCT (N = 6), cRCT (N = 4), quasi-experimental (N = 7), pre-post design (N = 5), cohort (N = 1), qualitative (N = 1), pseudo-random (N = 1), two-group comparison (N = 1) and one was a 2-year follow-up cross-sectional study. Five studies were feasibility or pilot studies. Study quality varied with 10 studies receiving a strong quality rating, 11 receiving a moderate rating, while four studies received a weak rating. Sample sizes varied widely between studies from N = 29 to N = 10,202.

Of the 25 interventions reviewed, 13 were considered universal mental health promotion programmes, five contained both promotion and prevention elements, six were considered primary prevention programmes and one intervention was a whole-school, multi-component health promotion intervention. The focus of the mental health promotion interventions varied and included the development of social and emotional skills, positive psychology, mindfulness and resilience, while two interventions focussed specifically on mental health literacy (see Table 1 for details). Interventions incorporating both promotion and prevention elements were skill-based or focussed on stress-reduction (see Table 2 for details). Prevention programmes focussed on anti-bullying, life-skills for “at-risk” students (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Kessler, Squicciarini, George, Baer, Canenguez, Abel, McCarthy, Jellinek and Murphy2015), cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents with subclinical depression (Singhal et al., Reference Singhal, Munivenkatappa, Kommu and Philip2018) and yoga to prevent depression, anxiety and aggression (Velasquez et al., Reference Velasquez, Lopez, Quinonez and Paba2015) (see Table 3 for details).

Table 1. School-based mental health promotion interventions in LMICs

Table 2. School-based mental health interventions containing both promotion and prevention elements in LMICs

Table 3. School-based primary mental ill-health prevention interventions in LMICs

All of the studies reviewed evaluated interventions that were delivered face-to-face in the school setting, apart from the study by Anttila et al. (Reference Anttila, Sittichai, Katajisto and Valimaki2019) which evaluated “DepisNet-Thai”, a web-based programme. Interventions were implemented in primary schools (N = 8), middle schools (N = 6) and secondary schools (N = 11). Participants ranged in age from 5 to 19 years and most were of lower socio-economic backgrounds living in areas of high poverty. Ten interventions were predominantly facilitated by teachers with the remaining programmes implemented by psychologists, researchers or trained external providers/community members. Training for facilitators varied in duration from 1 day to 1-week pre-intervention, with some studies reporting the provision of top-up training weekly, monthly, or midway through delivery. Two studies employed a “train-the-trainer” model, whereby teachers who received training then facilitated training for their peers (Kutcher et al., Reference Kutcher, Wei, Gilberds, Brown, Ubuguyu, Njau, Sabuni, Magimba and Perkins2017; McMullen and McMullen, Reference McMullen and McMullen2018). Fifteen interventions were developed in the implementing country. Seven were adapted versions of evidence-based programmes from HICs (Trip et al., Reference Trip, Bora, Sipos-Gug, Tocai, Gradinger, Yanagida and Strohmeier2015; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Weiss, Nguyen, Tran and Pollack2017; Kutcher et al., Reference Kutcher, Wei, Gilberds, Brown, Ubuguyu, Njau, Sabuni, Magimba and Perkins2017; Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Dang, Bui, Phoeun and Weiss2020; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Hanno, Ponczek, Pinto, Fonseca and Marchi2021; Seale et al., Reference Seale, Seale, Pande, Lewis, Manda, Kasanga, Gibson, Hadfield, Ogoh, McGrath and Harris2021), two were adaptations of programmes from other LMICs (Jegannathan et al., Reference Jegannathan, Dahlblom and Kullgren2014; Karmaliani et al., Reference Karmaliani, McFarlane, Khuwaja, Somani, Shehzad, Saeed Ali, Asad, Chirwa and Jewkes2020) and one was adapted from an evidence-based programme previously implemented in humanitarian settings (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, VanNattan and Gelkopf2018).

Positive outcomes were found for 10 of the 13 universal mental health promotion programmes reviewed and for all five of the interventions that incorporated both promotion and prevention elements (see Tables 1 and 2), with most studies receiving a moderate or strong quality rating. Studies evaluating skill-based interventions reported improvements in participants’ life skills, including self-awareness, self-management, resilience and relationship skills, positive behaviours and decreases in peer victimisation/perpetration, while mental health literacy programmes reported increased mental health knowledge and decreased stigma among students and staff. Improvements across a range of behavioural and mental health indicators were reported for participants of SEHER (SM), a whole-school, multi-component health promotion intervention implemented by lay counsellors and the study quality was rated strong (Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018), while null effects were reported for the only web-based programme reviewed (Anttila et al., Reference Anttila, Sittichai, Katajisto and Valimaki2019).

Improvements in positive outcomes, such as resilience, were found to be greater for ethnic subgroups in Sarkar et al. (Reference Sarkar, Dasgupta, Sinha and Shahbabu2017), highlighting the potential for life skills interventions to reduce disparities among ethnic minority groups. Programmes involving families and the wider community reported improvements in attitudes to suicide (Arenas-Monreal et al., Reference Arenas-Monreal, Hidalgo-Solórzano, Chong-Escudero, Durán-De la Cruz, González-Cruz, Pérez-Matus and Valdez-Santiago2022) and gender attitudes and reduced physical punishment at home which was more significant for females (Karmaliani et al., Reference Karmaliani, McFarlane, Khuwaja, Somani, Shehzad, Saeed Ali, Asad, Chirwa and Jewkes2020).

Outcomes for primary prevention programmes were more mixed. Considering anti-bullying interventions, only one study reported positive effects for one victimisation indicator for participants of the 4-week ViSC programme (Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020). Two of the three targeted interventions reviewed reported positive outcomes for “at-risk” participants of a Skills for Life programme (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Kessler, Squicciarini, George, Baer, Canenguez, Abel, McCarthy, Jellinek and Murphy2015) and students with subclinical depression who participated in a coping skills programme (Singhal et al., Reference Singhal, Munivenkatappa, Kommu and Philip2018).

Mental health outcomes were measured by 14 studies and considered happiness, life satisfaction, internalising mental health problems such as depression and anxiety and behavioural externalising problems. Most of the studies reporting on positive mental health outcomes evaluated skill-based interventions. Few studies measured academic outcomes with only two reporting positive programme effects. For participants of the teacher-led, ESPS stress-reduction programme, improvements in academic performance were found to be more significant for children living in an orphanage, highlighting the potential for programmes to reduce educational disparities among relatively disadvantaged young people (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, VanNattan and Gelkopf2018). Differential programme effects according to gender, level of adversity and risk were reported by some studies (see Tables 1 and 2 for details).

All 19 effective studies reported on some aspects of programme implementation, while 15 referenced monitoring fidelity of implementation. Quality of delivery was the most widely measured and reported domain and was monitored through session observations, audio recordings of sessions and facilitator reports. Seven effective studies reported on adherence, three on dosage and six on participant responsiveness. In terms of programme differentiation, shortening programme durations (Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020) and the delivery of whole-school interventions as class-based curricula (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Weiss, Nguyen, Tran and Pollack2017; Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020), may have adversely affected outcomes.

Most studies provided details on modules delivered. Eleven studies outlined the intervention’s underpinning theoretical model. Sessions were generally delivered weekly in participatory group-format, and most were between 45 and 60 minutes long (N = 10). Modules of skill-based interventions focussed on communication, self-awareness, self-control, relationships and coping skills. One study also included general health modules (Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Dasgupta, Sinha and Shahbabu2017), while three studies facilitated modules for families and/or school staff. Mental health literacy interventions included modules on positive mental health, stigma, understanding mental health and information on supports, while anti-bullying interventions focussed on developing social skills and recognising bullying. SEHER also incorporated general health modules in addition to modules on mental health, bullying, substance use, gender equality and violence (Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018).

Several moderators of effective implementation were identified in the reviewed studies. The main implementation barriers that were reported included large class sizes (Leventhal et al., Reference Leventhal, Gillham, DeMaria, Andrew, Peabody and Leventhal2015; McMullen and Eaton, Reference McMullen and Eaton2021), time constraints (Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018; Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2020), lack of ongoing support for teachers (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Dang, Bui, Phoeun and Weiss2020) and limited physical space (Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020). High teacher turnover due to community unrest was reported to have adversely affected implementation by McCoy et al. (Reference McCoy, Hanno, Ponczek, Pinto, Fonseca and Marchi2021), highlighting the importance of considering the effects of broader contextual and societal factors on programme implementation. Facilitators of implementation included adequate time for session delivery through the provision of dedicated timetable slots, after-school delivery or implementation in non-exam classes, the support of management and staff, adequate resources including physical space and a complementary school ethos. At a macro-level, effective partnerships, for example, with Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and communities, were highlighted as being key to programme delivery and sustainability.

Eleven studies referenced the cultural adaptation of programmes, with only four studies reporting details (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, VanNattan and Gelkopf2018; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Dang, Bui, Phoeun and Weiss2020; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Hanno, Ponczek, Pinto, Fonseca and Marchi2021; Seale et al., Reference Seale, Seale, Pande, Lewis, Manda, Kasanga, Gibson, Hadfield, Ogoh, McGrath and Harris2021). The adaptation process involved an initial assessment of the original programme with all stakeholders, subsequent adaptations including to language and content, piloting to check for cultural appropriacy and final adjustments following consultation with the implementation team. Youth involvement in the process was reported as facilitating natural cultural adaptation by Leventhal et al. (Reference Leventhal, Gillham, DeMaria, Andrew, Peabody and Leventhal2015), while involving the programme developers helped to ensure that the core components of the programme were retained (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Weiss, Nguyen, Tran and Pollack2017). Eight studies reported the translation of programme language, while Seale et al. (Reference Seale, Seale, Pande, Lewis, Manda, Kasanga, Gibson, Hadfield, Ogoh, McGrath and Harris2021) highlighted that the delivery of GROW through English excluded some younger students and considered its future delivery in local Zambian dialects. Some studies referenced adding culturally relevant content to programmes to increase participant responsiveness. Traditional folk stories and culturally applicable concepts like “shikamoo”, which refers to respect for the elderly, were incorporated into the ESPS programme (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, VanNattan and Gelkopf2018), while Seale et al. (Reference Seale, Seale, Pande, Lewis, Manda, Kasanga, Gibson, Hadfield, Ogoh, McGrath and Harris2021) reported incorporating local customs and a programme motto, “never give up, never surrender”, to GROW. Other studies rephrased terms such as “mental illness” to “mental health problems” and added references to national celebrities (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Dang, Bui, Phoeun and Weiss2020), sports (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Hanno, Ponczek, Pinto, Fonseca and Marchi2021) and dietary practices (Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Dasgupta, Sinha and Shahbabu2017). The involvement of key community members, such as pastors in programme delivery (Seale et al., Reference Seale, Seale, Pande, Lewis, Manda, Kasanga, Gibson, Hadfield, Ogoh, McGrath and Harris2021), and local healers who blessed the ESPS programme before it commenced (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, VanNattan and Gelkopf2018), was considered integral to the local acceptance of programmes.

Discussion

This scoping review sought to map the peer-reviewed and grey literature published from 2014–2022 on the process of implementing effective mental health promotion and prevention interventions in schools in LMICs. A total of 27 studies evaluating 25 school-based mental health interventions were identified. Although the studies spanned a wide geographical area consistent with other reviews (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013; Chuecas et al., Reference Chuecas, Alfaro, Benavente and Ditzel2022), a small number (N = 4) were from low-income countries. The increasing number of programmes with a mental health promotion focus and the number of interventions implemented in primary schools (N = 8) is encouraging and highlights the feasibility of implementing school-based programmes in LMIC settings. Most study designs were RCT, cRCT or quasi-experimental; however, mirroring findings from previous reviews (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021), study quality varied and only a few studies had longer follow-up periods, which would allow for better assessment of whether mental health outcomes were sustained. Reporting on implementation varied greatly between studies, and no study comprehensively measured all five domains of implementation. Overall, 15 effective studies reported implementation fidelity, with quality of delivery being the most widely measured domain. Consistent with previous literature (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Dowling and Barry, Reference Dowling and Barry2020), more significant positive effects were found when implementation quality was high. Eleven studies referenced the cultural adaptation of programmes, although as discussed in existing literature (Castro-Olivo, Reference Castro-Olivo2017; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021), few (N = 4) provided sufficient detail for replication or referenced employing an evidence-based adaptation framework to guide the process.

Of the interventions reviewed, universal skill-based mental health promotion programmes and skill-based targeted interventions for “at-risk” students and those with subclinical depression positively impacted young people’s life-skills and to a lesser extent mental health outcomes. As the literature suggests, there is a need to measure and report on mental health outcomes and to implement interventions of longer duration for significant mental health impacts to be achieved (Das et al., Reference Das, Salam, Arshad, Finkelstein and Bhutta2016; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020). Universal interventions that adopted a whole-school approach or involved families and communities produced more sustained effects, created environments supportive of positive mental health and impacted the wider determinants of young people’s mental health (Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018; Karmaliani et al., Reference Karmaliani, McFarlane, Khuwaja, Somani, Shehzad, Saeed Ali, Asad, Chirwa and Jewkes2020). Programmes that delivered general health modules in addition to life-skills and mental health modules yielded positive outcomes across a range of well-being and mental health indicators. In considering the largely null effects of anti-bullying interventions reviewed, preference should be given to longer-term, teacher-led whole-school approaches due to the complex nature of bullying (Arënliu et al., Reference Arënliu, Strohmeier, Konjufca, Yanagida and Burger2020), and its association with poorer academic outcomes and mental health difficulties (Sivaraman et al., Reference Sivaraman, Nye and Bowes2019). Previous literature has pointed to the potential for school-based mental health literacy programmes to decrease stigma in communities (Jorm, Reference Jorm2012) and both of the teacher-led mental health literacy interventions reviewed reported positive outcomes for increasing student and staff knowledge on mental health and decreasing stigma. Of note also were the differential programme effects according to gender, adversity and risk, endorsing the need to consider gender-specific components and comprehensive mental health initiatives in schools that incorporate both universal and targeted programmes (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill, Saeed, Servili and Rahman2020).

This research aimed to investigate the implementation process of reviewed programmes, and consistent with previous reviews, higher implementation fidelity yielded more positive programme effects. This is best demonstrated by comparing the positive, sustained effects of the multi-component SEHER when implemented by lay counsellors (SM) with the null effects when implemented by class teachers (TSM), who reported inadequate support and time for delivery (Shinde et al., Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018, Reference Shinde, Weiss, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2020). Previous reviews have pointed to the benefits of teacher-led, mental health interventions in low-resource school settings in terms of improved relationships with students, mental health and academic outcomes and cost-effectiveness (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013; Fenwick-Smith et al., Reference Fenwick-Smith, Dahlberg and Thompson2018; Gimba et al., Reference Gimba, Harris, Saito, Udah, Martin and Wheeler2020). However, as reported in Shinde et al. (Reference Shinde, Weiss, Varghese, Khandeparkar, Pereira, Sharma, Gupta, Ross, Patton and Patel2018), training and support for teachers and addressing any barriers to implementation is crucial to positive outcomes. Studies reporting a lack of physical space and materials for programme delivery highlighted the importance of careful planning and implementation support at the local level. Employing an implementation framework, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Reardon, Widerquist and Lowery2022), can help to guide the implementation process and map systems-wide barriers and facilitators to implementation. Finally, effective partnerships are considered crucial to health promotion (Corbin et al., Reference Corbin, Jones and Barry2016), and strong partnerships between schools, NGOs and partner universities were highlighted by many studies as facilitating the development, implementation and sustainability of interventions.

The potential for evidence-based interventions from HICs and other settings to be culturally adapted and effectively delivered and scaled-up in LMICs has been highlighted previously (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021; Jannesari et al., Reference Jannesari, Lotito, Turrini, Oram and Barbui2021), and several studies in this review referenced the role of cultural adaptation in positive outcomes and the external validity of programmes. However, few of the reviewed studies reported in any detail on the cultural adaptation process. Of the studies that did provide details, the involvement of key community figures in the adaptation process was considered to promote programme acceptance, while the input of programme developers was viewed as essential to ensuring that the core components of the programme were retained. While involving students in programme development was considered important in facilitating the natural cultural adaptation of interventions by Leventhal et al. (Reference Leventhal, Gillham, DeMaria, Andrew, Peabody and Leventhal2015), few other studies reported the involvement of young people in the process. Of the studies that reported positive outcomes and provided detail on the cultural adaptation of interventions, piloting the programme with young people to check for cultural appropriacy in advance of implementation emerged as a key stage of the process. Utilising a cultural adaptation framework such as the four-step heuristic framework for cultural adaptation (Barrera and Castro, Reference Barrera and Castro2006) or the eight-domain EVM (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995) could help guide the process and reporting on it in detail would allow for replication.

The findings from this scoping review show that school-based mental health promotion and prevention programmes, in particular interventions that focus on the promotion of positive mental health, are effective in increasing life-skills and prosocial behaviours and decreasing mental health symptoms and stigma for young people when implemented to a high level. The dearth of studies reporting on academic outcomes makes accurate conclusions on the impact of interventions on students’ learning in LMIC schools difficult to reach. However, previous reviews from HICs have pointed to the positive impact of teacher-led programmes on academic achievement and consequently employment opportunities in adulthood (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Oberle, Durlak and Weissberg2017).

This review highlights the critical importance of high-quality implementation of mental health promotion and prevention programmes in LMIC schools. The findings reinforce the need for more detailed research in this area, including measuring and reporting on implementation and investigating and addressing barriers to effective implementation so that programmes can be sustained outside of research conditions and scaled-up at a country level. The findings on cultural adaptation contribute to the dearth of literature in this area and endorse its crucial role in the local acceptance of programmes. The review also highlights the need for studies to provide adequate detail on the adaptation process. Metrics to determine the strength of evidence in relation to implementation effectiveness and cultural adaptation would provide useful information in addition to existing metrics assessing the quality of study design.

Strengths and limitations

This review maps the evidence of mental health promotion and prevention interventions in both primary and secondary schools in LMICs from 2014 to 2022. A comprehensive search strategy was employed to search numerous electronic databases and grey literature sources. The strengths of the review lie in the inclusion of all study designs, which detailed a variety of interventions and outcomes, giving the review depth.

Considering the study limitations, a more extensive grey literature search could have yielded many more relevant studies. In addition, due to time constraints, interventions implemented in humanitarian contexts were deemed special cases and excluded. Only studies published in English were included, thereby excluding many potentially relevant studies published in other languages.

Conclusion

This scoping review mapped the evidence of mental health promotion and prevention interventions in both primary and secondary schools in LMICs, examining the processes of implementation and cultural adaptation. Findings were generally positive and strengthen the evidence base of the effectiveness of school-based interventions in promoting young people’s mental health and well-being. Many studies were considered moderate to strong quality and several employed RCT or cRCT designs. The growing number of studies reporting on implementation is encouraging; however, there is a need for more stringent monitoring and reporting on implementation fidelity and the core components of programmes. Likewise, more robust research is needed on the cultural adaptation of interventions. In relation to intervention outcomes, measures of social and emotional well-being and positive mental health, academic outcomes, cost-effectiveness and longer-term follow-up periods are required to further strengthen the evidence base.

Current global policy frameworks endorse the need for a population approach to mental health promotion in key settings across the life-course, including in schools (UNICEF, 2021; WHO, 2021a). The number of effective interventions reviewed in this paper is promising and highlights the feasibility of implementing school-based programmes in LMIC settings. However, ensuring that programmes are culturally appropriate and implemented effectively will be key to the sustainability and scaling-up of interventions at a national level in order to improve the mental health and well-being of young people living in LMICs.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.48.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.48.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material.

Author contribution

Patricia Harte conducted the scoping review and was supervised by Margaret M. Barry. Patricia Harte and Margaret Barry designed the study and search strategy, and the original scoping review report was written up by Patricia Harte. Patricia Harte drafted this manuscript, and it was reviewed and edited by both authors prior to submission.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

WHO Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion Research

School of Health Sciences

National University of Ireland Galway

Ireland

30 October 2023

RE: Submission of “A scoping review of the implementation and cultural adaptation of school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions in low-and middle-income countries”

Dear Editor,

We would welcome your consideration of our paper of “A scoping review of the implementation and cultural adaptation of school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions in low-and middle-income countries” for publication in the journal Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

The attached paper reviews the evidence on the implementation, cultural adaptation, and outcomes of school-based interventions implemented in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). Much of the available robust evidence in the area of school-based mental health initiatives comes from high-income countries (HICs), and while evidence from LMICs has increased, there is a paucity of studies reporting on programme implementation and how it can be supported in under-resourced settings. Additionally, how evidence-based interventions from HICs and other settings can be culturally adapted for delivery in LMIC schools is under-reported in the literature.

This paper outlines the findings from a scoping review of the international peer-reviewed and grey literature concerning mental health initiatives in LMIC schools published from 2014-2022, following publication of the World Health Organisation Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. A grey literature search and the inclusion of all study designs allowed for detailed exploration of the implementation process of reviewed studies, including the barriers and facilitators to effective implementation in under-resourced settings and how barriers can be addressed. This review also investigated how interventions reviewed, which originated in HICs and other settings, were culturally adapted for delivery in LMIC schools, where details were provided. The programmes reviewed included mental health promotion interventions which were mostly skill-based, or focussed on positive psychology and mindfulness, developing resilience, or increasing mental health literacy. Some programmes contained both promotion and prevention elements, while prevention interventions included anti-bullying programmes and skill-based interventions for “at-risk” young people.

The results highlight the feasibility of implementing effective school-based interventions in LMIC school settings and the crucial role of effective implementation in ensuring positive programme outcomes. The number of studies reporting on implementation is encouraging, however, reporting varied greatly between studies with less than half of the reviewed studies outlining the intervention’s underpinning theoretical model and few studies measuring multiple domains of implementation. In terms of the adaptation of interventions to the local context, only four studies provided detail on the cultural adaptation process. The importance of culturally appropriate interventions and involving young people in the cultural adaptation of programmes to ensure that content is relevant to them is discussed, along with the need to retain the core components of original programmes. Conclusions are drawn and the need for more robust research endorsed, including studies with longer follow-up periods and more stringent monitoring and reporting on implementation and the process of cultural adaptation.

We believe that the paper will be of interest to readers of the journal.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Yours sincerely,

Patricia Harte