Introduction

The late 1950s and early 1960s nonviolent movement to desegregate Nashville, Tennessee—with its iconic lunch counter sit-ins—was not only an exemplary citywide movement. The direct actions of the Nashville movement did lead to a dismantling of Jim Crow in downtown public accommodations by 1962, two years before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It was, however, more than an exemplary citywide movement that achieved local results. By design, the Nashville movement was the chief vehicle for developing, diffusing, and training activists (e.g., Freedom Riders) in the nonviolence praxis adopted in 1957 by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) for deployment in the Southwide movement (Cornfield et al. Reference Cornfield2019; Halberstam Reference Halberstam1998; Isaac Reference Isaac and Hank2019; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016, Reference Isaac and Hank2020).

Sociologically, the Nashville movement, we argue, played a crucial role in the development and transmission of a movement praxis in a “dialogical” process of diffusion. As a model of movement diffusion, a dialogical diffusion process treats the diffusion of a movement praxis as contested, problematic, and nonlinear, and not as a foregone conclusion (Chabot Reference Chabot2012; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2016, Reference Isaac and Hank2020). Indeed, during the civil rights movement of the 1958–62 era, nonviolence praxis faced two major challenges. First, the established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), co-founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1909, had championed civil rights and desegregation through litigation in the courts and was unsupportive of the SCLC’s new tactical turn to a community-based praxis of nonviolent direct action following the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–56, although some local NAACP chapters did engage in nonviolent direct action (Chabot Reference Chabot2012). Second, many Black young adults were skeptical of the requisite, tremendous self-restraint required for engaging in nonviolent direct action in the face of the profound indignities and violence hurled by hostile Whites at the nonviolent protesters (Cornfield et al. Reference Cornfield2019; Halberstam Reference Halberstam1998; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016, Reference Isaac and Hank2020).

Research on the dialogical diffusion of social movements has tended to emphasize the discursive strategies and tactics for surmounting obstacles to movement diffusion. Chabot’s (Reference Chabot2012) model of transnational dialogical diffusion, based on the diffusion of Gandhian nonviolence praxis from India to the mid-twentieth-century US civil rights movement, consists of three stages: (1) “translation” of the original praxis into terms that resonate in the cultural repertoire of contention of the receiving nation; (2) “experimentation” with the new praxis in the receiving nation; and (3) “implementation” of the new praxis in the receiving nation. Together, the three stages constitute a decades-long mobilization of a movement praxis in a process Chabot (Reference Chabot2012) calls “collective learning” by which activists in the receiving nation come to adopt, adapt, and deploy the new praxis.

In this article, we extend Chabot’s research in two ways. First, in Chabot’s model, collective learning drives dialogical diffusion with the publication and dissemination of ideas among intellectual activists and theologians. Less attention is given to the impact of agency, strategic action, and especially “bridging” (Robnett Reference Robnett1996) by activists who connect simultaneously the translation, experimentation, and implementation stages into a coherent course of action. As we show, the Reverend James M. Lawson Jr. was the chief activist and “bridge leader” (Robnett Reference Robnett1996) who linked three generations of activists (Cornfield Reference Cornfield1989, 2015; Klatch Reference Klatch1999; Pagis Reference Pagis2018; Whittier Reference Whittier, Meyer and Sidney2018) in driving simultaneously the three stages of the dialogical diffusion of Gandhian nonviolence by way of the Nashville movement. Second, Chabot’s model contextualizes dialogical diffusion in the cultural repertoire of movement tactics that prevail in a nation. Less emphasis is given to the range of factors—historical, demographic, and spatial factors—that facilitate activism and the requisite bridging of activist generations for collective learning and dialogical diffusion of a movement praxis.

The purpose of our article, then, is to induce and describe a new intergenerational model of movement mobilization as a vehicle for dialogical diffusion from the Nashville case. Furthermore, as we show in the following text, the Nashville dialogical process was contextualized in a set of historical, demographic, and spatial conditions that facilitated Lawson’s strategic bridging actions in the dialogical diffusion of nonviolence praxis. In our three-generation model of activism, the three activist generations enact the several stages of Chabot’s diffusion model, respectively.

Our article contributes to the literature on bridge building in social movements as well (e.g., Coley Reference Coley2014; Coley et al. Reference Coley, Raynes and Das2020; Gawerc Reference Gawerc2020; Isaac and Christiansen Reference Isaac and Lars2002; Mayer Reference Mayer2009; Robnett Reference Robnett1996; Snarr Reference Snarr2009), addressing the factors that encourage intergenerational solidarity within social movements. The Nashville movement was an instance of planned, intergenerational movement mobilization. King and Lawson, as members of what we call the “SCLC generation,” planned a series of local nonviolent direct actions in the late 1950s that would involve hundreds of college-student activists, many of who would become affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Lawson was mentored by A. J. Muste, a White member of the older “pacifism-nonviolence generation” who chaired the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). The younger “SNCC generation” that Lawson worked to mobilize engaged in local direct actions, such as the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, supported by local older professionals, including clergy, lawyers, and journalists. Our intergenerational model strives to capture how the SCLC’s strategic actions, akin to Blee’s (Reference Blee2012: 37) “turning points”—that is “major alterations in direction”—linked the SCLC to a large and growing, local college-student mobilization in a movement whose three generations of activists were, respectively, distributed across national and local levels of mobilization (Miller and Nicholls Reference Miller and Walter2013; Nicholls Reference Nicholls2007).

We thus contribute to the literature on bridge building in social movements in several ways. First, we take seriously the idea that many social movements must tend to intramovement divisions related to age, an attribute rarely considered in this literature (but see Cornfield Reference Cornfield1989, 2015; Whittier Reference Whittier, Meyer and Sidney2018). Previous literature instead highlights the role of bridging organizations and bridge leaders in bridging intramovement divides and tensions related to race, national origin, social class, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious identity, and other forms of social difference (e.g., Coley Reference Coley2014; Coley et al. Reference Coley, Raynes and Das2020; Gawerc Reference Gawerc2020; Isaac and Christiansen Reference Isaac and Lars2002; Mayer Reference Mayer2009; Robnett Reference Robnett1996; Snarr Reference Snarr2009). Our multistage mobilization model addresses the lack of attention to age-related divides by highlighting distinct roles of different age generations in historically and qualitatively distinct stages of mobilization.

Second, we consider the societal conditions under which social movements decide to engage in intergenerational bridge building, highlighting the role of historical strategic turning points, demographic change, and the spatial array of sites of movement mobilization. By the mid-1950s, the civil rights movement began to shift toward the tactic of nonviolent direct action as the NAACP tactic of litigation met with substantial resistance in the implementation of desegregation plans in schools and public transportation (Morris Reference Morris1984). The intergenerational mobilization modeled by the Nashville movement emerged at a time of tactical change that also coincided with and linked itself to mounting college-student enrollments by the baby boomer generation (Halberstam Reference Halberstam1998; Kinzie et al. Reference Kinzie, Megan, John, Don, Jacob and Heather2004), and this applied to Black as well as White students.

Third, we consider biographical characteristics of those activists who do engage in bridging age generations that, in a dialogical process of collective learning, consists of intergenerational mentoring in a new movement praxis (Cornfield Reference Cornfield1989, 2015). Specifically, James Lawson, we argue, was particularly well-positioned to bridge generational divides not only because his SCLC generation fell between the younger SNCC and older pacifism-nonviolence generations. Lawson was also predisposed to serving as both mentee of the older generation and mentor of the younger generation due to his status as both a student and religious leader and because of his deep familiarity with African American religious traditions.

Accounting for the challenges of intergenerational mobilization, and thus accounting for the involvement of students in a movement planned by more senior adults, is an important task because the students were the youngest generation of Nashville-based activists who went on to diffuse nonviolence praxis throughout the South. Students emerging out of the Nashville civil rights movement were among the founders and early leaders of SNCC in 1960; were responsible for continuing a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)–launched Freedom Ride that had been halted in Alabama in 1961; and played a part in the Albany campaign of 1961–62, the Birmingham campaign of 1963, the March on Washington in 1963, the Freedom Summer campaign of 1964, the Selma campaign of 1965, the Chicago campaign in 1966, and the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike of 1968 (Cornfield et al. Reference Cornfield2019; Finley et al. Reference Finley, Bernard, Ralph and Pam2016; Isaac Reference Isaac and Hank2019; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016, Reference Isaac and Hank2020). Martin Luther King Jr. said the Nashville movement represented “the best organized and the most disciplined in the Southland” (qtd. in Lewis Reference Lewis1998: 111), and historian Clayborne Carson (Reference Carson1981: 16) wrote, “[i]t was these Nashville activists, rather than the four Greensboro students, who had an enduring impact on the subsequent development of the southern movement.”

Our analysis draws on rich qualitative data on 63 members of the Nashville civil rights movement, including oral history interviews conducted by the senior co-authors with 36 members of the Nashville civil rights movement, oral history interviews held by the Nashville Public Library with 15 additional members of the Nashville civil rights movement, and historical data on 12 other participants culled from secondary sources (see Isaac et al. 2016 and Reference Isaac and Hank2020 for full details on the oral history methodology). Later in the article, we describe the details of a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) strategy for analyzing our interviews with a subset of student participants.

Three Activist Generations

At the time of the Nashville movement, Lawson enlisted and coordinated three activist generations in the diffusion of nonviolence praxis as he and the SCLC circumvented a fourth activist generation, namely, that associated with the NAACP. We refer to an activist generation as a birth cohort of activists who adhere to the same movement praxis. Activist generations differ by birth cohort (generations), ideology, and tactics because they enter adulthood during different historical “turning points” in the cumulating and differentiating, ideological and tactical course of an ongoing social movement (Cornfield Reference Cornfield1989, 2015; Pagis Reference Pagis2018; Whittier Reference Whittier, Meyer and Sidney2018). We determined activist-generation time bands inductively and link each activist generation to a key civil rights organization that tended to embody that activist generation’s attitudes about strategies and tactics. As Stinchombe (Reference Stinchcombe2000) wrote, organizations are stamped with the historical conditions under which they were founded, and such stampings have ongoing consequences for those organizations and their members (see also Zald and Ash Reference Zald and Ash1966: 332–33).

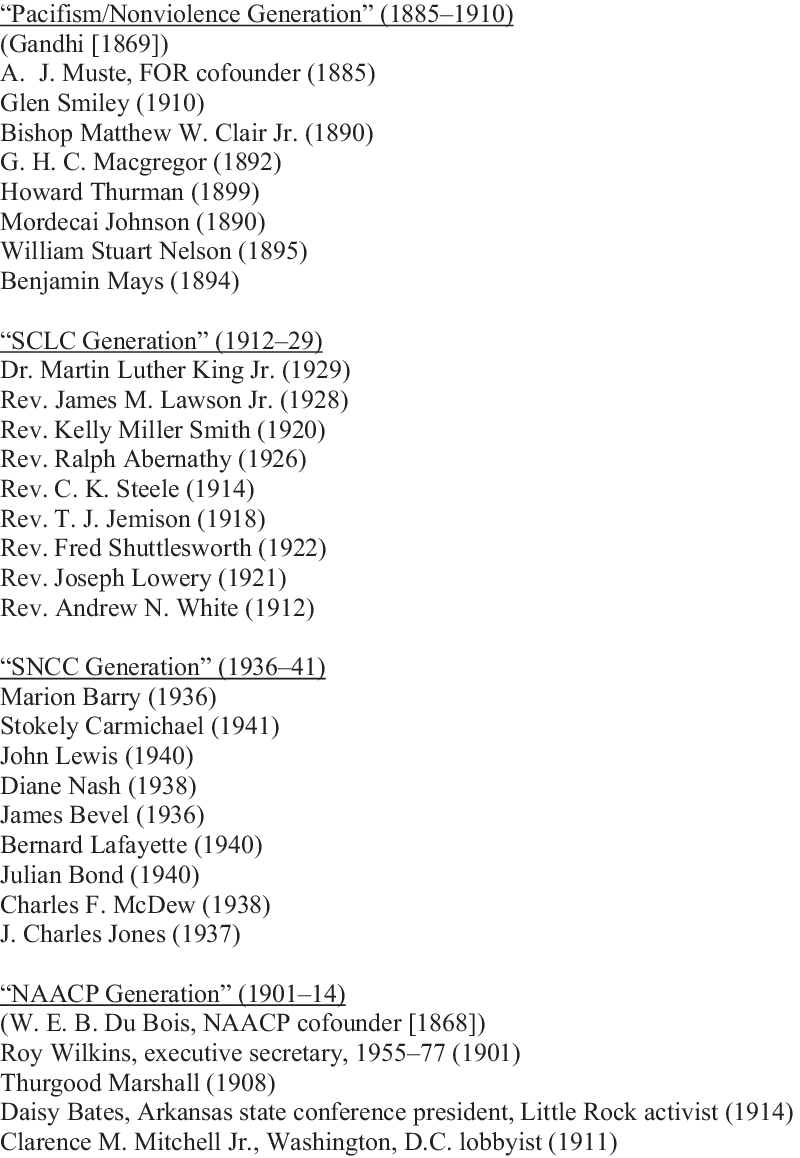

Lawson was part of the SCLC generation but worked beyond it, bridging three activist generations, shown in figure 1.Footnote 1 We refer to the first as the “pacifism-nonviolence generation,” comprised of people who were born between 1885 and 1910. This generation of intellectual-activists adhered to Gandhian nonviolence and/or pacifism and developed and applied these ideologies to the pursuit of racial justice in Europe and the United States. Some of them directly mentored and collaborated with Lawson during the 1940s and 1950s, including A. J. Muste, Glen Smiley, and Bishop Matthew W. Clair Jr., while others produced scholarly works linking Gandhian nonviolence, pacifism, prophetic Christian theology, and the pursuit of racial justice in the United States (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012). A cluster of Black religious intellectuals at the School of Religion at Howard University in Washington, D.C. in the 1930s and 1940s focused on training, according to Dean Benjamin E. Mays, “an insurgent Negro professional clergy.” Mays’s colleague, Howard Thurman, and his successor, William Stuart Nelson, at different times, traveled to India to confer with Gandhi about the possibilities of adopting nonviolent tactics into the African American freedom struggle. Their students at Howard, James Farmer, a cofounder of the Congress of Racial Equality, and Kelly Miller Smith and Andrew White, leaders in the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference, linked to a succeeding generation of Southern civil rights activists (Dickerson Reference Dickerson2005, 2014; Jelks Reference Jelks2002).

Figure 1. Activist Age Generations at the time of the Nashville movement (birth years in parentheses and brackets).

The second activist generation, whom we term the “SCLC generation,” was born between 1912 and 1929. This activist generation comprised the group of Southern African American preachers who championed the tactical turn to nonviolent direct action that led to the formation of SCLC in 1957 under the leadership of the youngest member of their generation, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In light of Lawson’s expertise in the Gandhian teachings of the pacifism-nonviolence generation, King recruited Lawson, who was approximately the same age as King, in 1957 to implement the nonviolence praxis embraced by the SCLC generation, thereby initiating Lawson’s bridging role in linking the first two activist generations and Lawson’s broader role of diffusing nonviolence praxis into the Southern Black struggle for realizing civil rights and racial justice.

We refer to the third activist generation as the “SNCC generation,” born between 1936 and 1941. This generation, comprised of college students at the time of the 1960s-era nonviolent movement, included the Nashville core cadre of activists. This core cadre of college-student activists, trained by Lawson in intense nonviolence workshops (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016), sat down at the Nashville lunch counters, assumed leadership positions in the movement, and went on to become Freedom Riders championing nonviolence and desegregation throughout the South. The core cadre included the likes of James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian.

The nonviolence praxis of the early SNCC generation is partly depicted in SNCC’s founding philosophy crafted by a “fiery Lawson,” as Payne (Reference Payne2007: 96) described him, at the founding SNCC gathering of some 120 college-student activists at Shaw University in North Carolina in 1960 (Carson Reference Carson1981: 20). Lawson, who was accompanied by the Nashville core cadre, was considered by some to be “the young people’s Martin Luther King” and received a standing ovation at the SNCC gathering (quotation from Payne Reference Payne2007: 96; also, see Carson Reference Carson1981: 23). Lawson’s Gandhian-Judaic-Christian SNCC philosophy statement, excerpted here from Carson (Reference Carson1981: 23–24), read in part:

We affirm the philosophical or religious ideal of nonviolence as the foundation of our purpose…. Nonviolence as it grows from Judaic-Christian traditions seeks a social order of justice permeated by love…. Through nonviolence, courage displaces fear; love transforms hate … justice for all overthrows injustice. The redemptive community supersedes systems of gross social immorality…. By appealing to conscience and standing on the moral nature of human existence, nonviolence nurtures the atmosphere in which reconciliation and justice become actual possibilities.

Marion Barry, one of the Nashville core cadre, was elected SNCC chairman at the SNCC gathering.

In sum, each of the three generations comprises a birth cohort of activists of a specific ideology who were present during the tactical turn of the civil rights movement during the 1950s, or whose theologies and political orientations informed Lawson’s subsequent formulation and application of Gandhian nonviolence praxis to the Southern civil rights movement during the 1950s. A fourth generation, whom we label the “NAACP generation,” comprises the leading NAACP activists from whom the SCLC generation departed tactically and whom Lawson circumvented as he diffused nonviolence praxis across the three other generations during the late 1950s and early 1960s (Carson Reference Carson1981: 23). In terms of age, the NAACP generation fell roughly between the pacificism-nonviolence and SCLC generations (see figure 1).

Three-Stage Intergenerational Mobilization Process

Our intergenerational model of mobilization unfolds in three stages. In the first stage of site selection, senior national movement leaders (pacifism-nonviolence and SCLC generations) select and transform a place (e.g., a city) into an exemplary site of transformative social action (Miller and Nicholls Reference Miller and Walter2013; Nicholls Reference Nicholls2007). In the second stage of tactical design, national and local senior and younger local movement leaders (SCLC and SNCC generations) in the selected site establish preparation paths (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2016) and design local collective actions that (1) align with the values and priorities of both the national movement leadership and local residents and (2) deploy the local built environment (e.g., boulevards, lunch counters, movie theaters) and local human resources (e.g., the large college student population) for disruptive display and diffusion of movement visions, values, and objectives (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012). In the third stage of biographical convergence, local individuals (usually students of the SNCC generation), arriving on independent biographical pathways to the site, self-select into established preparation paths based on the alignment of their biographical availability and prior politicization (Becker Reference Becker, Powell and Richard1984; Coley Reference Coley2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Thomas2017; Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Lowell2018).

Stage 1: Site Selection of Nashville by National Leaders

Senior national civil rights leaders of the pacifist-nonviolence and SCLC generations selected Nashville as a site for exemplary, nonviolent direct action at a pivotal moment in the course of the Southern civil rights movement. Until the mid-1950s, the movement to dismantle Jim Crow and desegregate the South was guided primarily by the NAACP tactic of legal action to desegregate schools. By the time of the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, the tactic of nonviolent direct action was gaining traction, especially with segregationist resistance to the NAACP itself and to desegregation in Alabama and elsewhere in the South. The NAACP, however, opposed the tactic of nonviolent direct action, leading Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others to form the SCLC in Atlanta in January 1957.

The SCLC was formed to implement what can be characterized sociologically as a multicity mobilization of nonviolent protest. In the SCLC’s words, the organization was formed to serve “as a coordinating agency for local protest centers that were utilizing the technique and philosophy of non-violence in creative protest…. Affiliate organizations all across the South make up the body of the Conference. The making and execution of basic policy is the responsibility of the Executive Board, geographically representative of the entire South” (Southern Christian Leadership Conference 1961b).

One month later, King recruited the Reverend James M. Lawson Jr., who was a graduate divinity school student at Oberlin College in Ohio and approximately the same age as King, to design and implement the SCLC’s strategy of engaging in multiple local, nonviolent direct actions throughout the South. Lawson, a member of FOR, had immersed himself in Gandhian praxis in India for two years. He then enrolled at Oberlin in Fall 1956 to study “some specialty in Jesus, and not Paul, but Jesus, … the study of Jesus” (Lawson Reference Lawson2016; also see Dickerson Reference Dickerson2014; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012; Morris Reference Morris1984). The news of the Montgomery bus boycott, which he learned while he was still in India, inspired him to work with King and the emerging nonviolent movement in the South. When Martin Luther King Jr. came to lecture at Oberlin, Lawson had a chance to meet with him. Lawson (Reference Lawson2016) recounts his private, face-to-face meeting with Dr. King at Oberlin on February 6, 1957, as follows:

I walked through the door, I was the first person there and after I got halfway across the room I heard motion at the door and it was Martin King walking in by himself…. So there he is and I, we sit down and talk at length. Well we clicked, he was very interested in the fact that I’d just returned from India, he said among other things that he hoped he could go to India one day and learn much more about Gandhi and Nehru … then eventually in our conversation I told him that when I finished my graduate degrees one of the places I wanted to work was in the deep South as a pastor so I would be moving south. That’s when he said “come now, don’t wait, we need you now” and then he went on to talk about that need … one of the things he said was we don’t have anyone who has that kind of background and knowledge of nonviolence or Gandhi, we have no one like that he said, no one like you. By this time he knew A.J. Muste, he knew Bayard Rustin by the time, so he said we have no one like you … he knew I was a practicing devotee of nonviolent struggle…. King says to me, we’re looking face to face at each other like this, we’re talking, and King says to me “come now.” Well what the heck? I recognized that inside I became very, very, very still. By the time he stopped that paragraph of the conversation I knew this was a major moment in my life and I heard myself answering him very, very quietly but very still because I had not the faintest idea how this was going to happen or how I would do it. I just simply said to him, “I’ll come as soon as I can.”

Reverend Lawson arrived in Nashville in January 1958 as the Southern field secretary of FOR (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012). He did movement work full-time until he enrolled as a divinity student at Vanderbilt University in Fall 1958. Having consulted with A. J. Muste and FOR national field director Glenn Smiley (Lawson Reference Lawson2016), Lawson selected Nashville as his base of operations for several reasons:

-

1. He could continue his graduate studies at the Vanderbilt University Divinity School;

-

2. The Nashville headquarters of his denomination, what is now known as the United Methodist Church, provided him with a community with which he was already familiar;

-

3. The city would likely provide a softer version of Jim Crow than a city such as Atlanta;

-

4. There was a heavy presence of colleges, especially traditionally Black institutions—Fisk University, Tennessee A&I University, Meharry Medical College, and American Baptist Theological Seminary; and

-

5. The city was centrally located in the region, which was beneficial for travel in all directions (Lawson Reference Lawson2007).

By 1961, Nashville became known as the exemplary training center for nonviolent direct action in the civil rights movement. The 1961 annual meeting of the SCLC convened in Nashville in September on the theme of “The Deep South in Social Revolution.” Meeting headquarters were in the Clark Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the churches where Lawson conducted his nonviolence workshops. Among those listed on the program were SCLC President Dr. King; SCLC Chaplain the Reverend Kelly Miller Smith of the NCLC, presiding over the conference; Harry Belafonte, who was scheduled to give a concert in tribute to the Freedom Riders at the Ryman Auditorium; Guy Carawan of the Highlander Folk School, leading a Freedom Sing; William Kuntsler of the American Civil Liberties Union, speaking on the “Legal Significance of the Freedom Ride Trials to Interstate Travel”; Spottswood Robinson, Dean of the Howard University Law School, speaking on “The Role of the Civil Rights Commission in Social Revolution”; the Reverend Andrew Young, delivering a devotional prayer; James Farmer, National Director of the Congress on Racial Equality, speaking on “Nonviolence and Social Revolution”; and SNCC member and SCLC Staff Workshop Director the Reverend James M. Lawson Jr., delivering the keynote address (Southern Christian Leadership Conference 1961a).

Stage 2: Tactical Design in Nashville

Martin Luther King Jr., then, played a key role in drawing James Lawson, already a dedicated practitioner of nonviolence, to the South, as well as establishing Nashville as a key center of the civil rights movement. How did local movement leaders, in turn, go about designing tactics for desegregating downtown Nashville? Arriving in Nashville, Lawson quickly connected with senior local leaders of the SCLC generation, including the Reverend Kelly Miller Smith (Smith Reference Smith1964: 4), to lay the groundwork for the sit-in campaign. Lawson knew that the tactical approach taken by the Nashville movement would need to build on the tactical momentum of the Montgomery bus boycott. As Lawson (Reference Lawson2016) put it, “I knew we had to demonstrate that Montgomery could be repeated in other ways out of a methodical, systematic approach. And that was what I put down on the table for [the Reverend Kelly Miller Smith of Nashville] and that’s what I put down on the table for myself.”

Lawson’s (Reference Lawson2016) Gandhian method for arriving at their nonviolent tactical approach consisted of four steps. The four steps constituted a nonlinear, iterative process of designing and implementing nonviolent direct action:

-

1. Focus is the determination of local community priorities. Throughout early 1959, Lawson conducted community meetings with local residents about their concerns. Multifaceted “humiliation of downtown shopping” was among the chief concerns that surfaced in these meetings.

-

2. Negotiations allow protesters to bargain with their adversaries in realizing movement objectives. In Nashville, activists decided not to pursue negotiations prior to the sit-ins but would return to this step afterward to negotiate with, for example, department store owners and managers to remove “whites-only” signage.

-

3. Direct action included especially the sit-ins at lunch counters, restaurants, libraries, train and bus stations, and so forth, but would also include stand-ins at movie theaters, economic boycotts, picketing, and marches. The direct action would also necessitate mobilization of community support, or gaining the support from the Black and White community for the movement actions and objectives.

-

4. Follow-up is movement self-evaluation. According to Lawson (Reference Lawson2016), a campaign had to “have evaluation of what [it’s] done, … of the changes that have been initiated.” The campaign also has “to have a … watchdog over those changes to see to it that the changes do move and do happen.” For example, “if the [downtown Nashville] merchants agree to change and to begin the process then the campaign leadership in one way or another had to then do the following up to be sure the changes were initiated … [the Nashville Christian Leadership Council] and Kelly Miller Smith and a few others did that very, very well.”

As Lawson and Smith undertook the first step of their process, determining local community priorities, they initially only worked with adults from the Nashville area, primarily clergy and church-attending women, ages 27–50. Lawson (Reference Lawson2007) did not recall any college student in the early workshops and further noted that the decision to desegregate the downtown area of Nashville was one made by the group, especially women who attended the discussions. Lawson (Reference Lawson2007) discussed why desegregating downtown was important to these women:

[The] whole discussion of downtown Nashville and its humiliation was caught up in this society where you had these white/colored signs everywhere and where people could not sit down anywhere, and this came out in those January, February, May [community] meetings [in 1959], no one could sit down to get a cup of coffee. A woman could not shop and stop—and one of the important points that came up in this process, again which I did not know, that on the third floor … of Harvey’s Department Store there was a carousel for children and mothers, and where you could get a sandwich or cup of coffee. That’s the first I heard of that. But the women [at the community meetings] pushed very hard at all of that, this is humiliation, we can’t sit there and have a cup of coffee while our children play in these swings and merry-go-round.

It was Lawson (Reference Lawson2007) who pushed the group to consider the tactic of sit-ins to desegregate such downtown stores and to move quickly to this direct action phase rather than spend time negotiating:

I had decided that if we were going to go after desegregating downtown Nashville … that one of the easiest forms of action … was the sit-in. It was one of the most practical ones. Not picketing, not an economic boycott, not parades or marches, I said as I tried to strategize through and hearing what people were saying. I had concluded that strategically the sit-in would be the best weapon to begin with … I knew we were going to start with that as the very best tactic to begin with … I also discovered and recognized in June and July [1959] that our negotiating process would begin informally in the action, [but] we should begin with the action first and then begin with the processes of negotiating. I also … became convinced that we would do some testing, and in that testing we would do some negotiation. I also knew that I wanted to get Will Campbell to start some informal negotiating through some of his work to figure out what merchants were saying and thinking about change…. Therefore the preparation that we needed to do first was to do direct action using the sit-in, and do it in a number of restaurants and counters [authors’ italics].

Eventually, having agreed to focus on desegregating Nashville’s downtown, and having helped to convince the adults of the necessity of nonviolence, Lawson (Reference Lawson2009) decided they should proceed to step three and launch the sit-in campaign. To do this, the group knew they needed to recruit students who would have the time and energy to engage in the sit-ins, but they decided high school students, with whom community members generally had closer connections compared to more transient college students, would be inappropriate for the campaign:

JL: Yes, we said we want to recruit students. And there was some talk about should we do high school students, and if I remember correctly there was a frowning upon doing high school students. So we did not officially recruit high school people. I’m pretty sure that was right.… These were the major sources of our power to demonstrate, the students. So a central committee should not be an all-NCLC group or an all-community group, that it should have the major source of our athletes for change, our people who were willing to risk themselves in the demonstrations. And they were the freest people to demonstrate.

DC: The students.

JL: Yes, absolutely. And this was true, we knew this to be true. Their parents working were not available. They may have been on Saturday but they weren’t available during the week. But their parents would be people who recognized the risks to jobs, the risk of getting blacklisted in such a fashion that they would no longer be able to make a livelihood. This is what happened to Rosa Parks and her husband in Montgomery. They finally had to leave because they could get no work whatsoever.

In the fall of 1959, Lawson began conducting nonviolence workshops and testing community reactions to preliminary lunch-counter “test” sit-ins in Nashville as training for adults and college students in nonviolence praxis (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2016; Lawson Reference Lawson2007; Nashville Christian Leadership Council 1961). These workshops and preliminary sit-ins in December led to the visible downtown Nashville lunch-counter sit-ins that took place in February 1960 and to the Freedom Rides that occurred in May 1961. But how would they go about recruiting these college students who would play such a pivotal role in the direct action campaign?

Stage 3: Biographical Convergence in Nashville

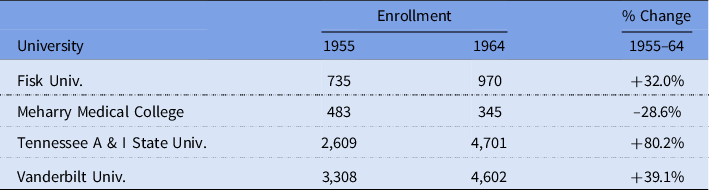

The pool of prospective “biographically available” college-student activists had increased rapidly in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. The pivotal tactical turn by the civil rights movement toward nonviolence coincided with the dramatic increase in college enrollments in the United States. With the passage of the GI Bill (1944) and the National Defense Education Act (1958) and the establishment of the United Negro College Fund (1944), college enrollments, including at historically Black colleges and universities, surged after World War II (Kinzie et al. Reference Kinzie, Megan, John, Don, Jacob and Heather2004: 8–9). The enrollment surge was especially pronounced among public institutions of higher education. Between 1955 and 1964, total US college enrollment increased by 95.2 percent, and the number of Black students enrolled in private and public colleges increased by 13.0 percent and 164.0 percent, respectively (US Census Bureau 2017).

College enrollments in Nashville increased between 1955 and 1964, as shown in table 1. Consistent with national patterns, enrollments increased the most at historically Black state university Tennessee A & I, while college enrollments increased at a moderately high rate at the historically Black and predominantly White, private universities—Fisk and Vanderbilt Universities, respectively. Enrollments declined at historically Black, private Meharry Medical College.

Table 1. Percentage change in fall opening enrollments in selected Nashville-area universities, 1955–64

Source: U.S. Office of Education (1956), table 12, pp. 40–41; U.S. Office of Education (1964), table 7, p. 70.

Black college students arrived in Nashville on diverse, converging biographical pathways during the late 1950s and early 1960s (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016). But what precisely were the characteristics of these student activists? Through inductive analyses of our oral history interviews, we identified several characteristics that theoretically could have made them willing to participate in a civil rights campaign yet resistant to planning by an older generation of leaders (Becker Reference Becker, Powell and Richard1984; Coley Reference Coley2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Thomas2017; Frenette Reference Frenette2019; Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Lowell2018): (1) a birthplace and home outside of Nashville, indicating these students’ formative experiences took place outside of Nashville’s Black community and movement infrastructure (even as these formative experiences may have been themselves quite diverse); (2) prior movement experience, often while still in high school and generally in campaigns prior to arriving in Nashville, demonstrating that these students’ willingness to participate in direct action again not initially cultivated by Nashville leaders; (3) a political motive for choosing to attend college in Nashville, indicating their desire to continue participating in direct action in Nashville in particular was not initially inspired by Nashville leaders; and (4) attendance at one of Nashville’s private colleges and universities (e.g., American Baptist College, Fisk University, Vanderbilt University), which tended to provide more space for social activism than Tennessee A & I, the historically Black public university in Nashville.

First, local Nashville activists observed that those students who participated in the Lawson workshops, and who would go on to form the leadership cadre of the Nashville movement, tended to have originated in places other than Nashville. Native Nashvillian and former Freedom Rider Rip Patton (Reference Patton2008) recounted a conversation he had had with his fellow Nashville activists about the Nashville movement student leaders:

we talked about the fact that … Diane Nash, John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, these people came from different places in the United States. They had different ideas as to what they wanted to do with their lives … going into college…. All these people came together to form the student movement. That was the student committee and so … I have said that this was all God’s plan.

Those whose families lived outside Nashville, but who subsequently came to Nashville for college, would go on to have more opportunities to extensively participate in the movement because their family would not be around to hold them back out of fears for their safety, as would happen with many of the students who grew up in Nashville.

Second, a few students reported prior participation in social movement (usually civil rights movement) activism. Some of these students had engaged quite extensively in civil rights campaigns before arriving in Nashville. As an example, C. T. Vivian (Reference Vivian2008) describes involvement to desegregate lunch counters and restaurants in Peoria, Illinois, as early as 1947:

I had my first nonviolent direct action movement in Peoria, Illinois after I’d left Macomb, in fact it was nine years before Montgomery. So we were already doing nonviolent direct action…. James Farmer had moved in Chicago his CORE and that was the first of the real popular actions. A group of us got involved in Peoria and we opened all the lunch counters and restaurants in Peoria.

Other students with such prior participation in social movements included Marion Barry and Bernard Lafayette. Such prior participation in civil rights activism cemented some students’ desire to participate in civil rights activism in Nashville.

Third, a number of students reported that they chose to come to Nashville for college for political reasons. Gloria Johnson Powell (Reference Powell2009), for example, grew up in Boston, and showed evidence of politicization from a young age: she participated in a local Freedom House that debated political issues in the United States. As early as the eighth grade, she decided never to salute the flag, believing her allegiance “belonged to the whole world” instead. She attended Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, majoring in sociology, where she learned more about social issues facing the United States. However, she decided to travel South and go to graduate school at Meharry Medical School in Nashville because she hoped to desegregate the South:

LI: Coming out of Mount Holyoke could you talk a little bit about how you made the decision to come to Nashville?

GJP: Well at Mount Holyoke you know they were doing the Little Rock thing and we were talking about it.… I met a young man from Yale and he had gone to Morehouse, and he knew that I wanted to go to medical school, and he said go South, you need to go to the South because so much is going on. He had come from Michigan, he said, and it’s going to be just incredible. I was majoring in sociology and doing all the things for medical school…. So I said where can I go to medical school in the South? He said well there’s Howard in Washington, D.C., and I had known that, but he said there’s an all-black one in Nashville. I had never heard of Meharry. And then I found out later that my mother’s cousins had gone to Meharry, but nobody had ever told me. It seemed to me as someone who was specializing in sociology, and knowing the kind of lack of healthcare that blacks had gotten in the South, that I needed to understand all of it. As a sociologist or what have you, I needed to understand it.

She initially “hated” Meharry and pondered transferring to another school, but once she heard about the opportunity to attend the nonviolence workshops, she was excited, because it confirmed her reason for coming to the South:

LI: Now with this experience in the workshops and a connection to a wider group of people, did that make any difference for you?

GJP: That’s why I had come South.

LI: Okay, that’s why you came South. So now you’re not thinking about maybe transferring, but staying…?

LI: Exactly.

Others who decided to attend their particular colleges and universities for political reasons included White exchange students at Fisk such as Candie Carawan and Jim Zwerg, who both excitedly accepted invitations to attend Lawson’s workshops.

Finally, Will Campbell (Reference Campbell2008) added that it was the students enrolled at the historically Black private colleges and universities, more than those enrolled at the state university Tennessee A & I or in public high schools, who tended to become Lawson workshop participants and form the core cadre. Referring to Tennessee A & I, Campbell (Reference Campbell2008) argued that “being a state school, the administration held a little tighter rein on” student activism than the private institutions. Similarly, former A & I student and Freedom Rider Catherine Burk Brooks (Reference Brooks2009) surmised that the A & I university administration opposed the nonviolence workshops, compelling the A & I students to attend workshops held in the vicinity of Fisk University. Indeed, in May 1961, Tennessee A & I (later renamed Tennessee State University) expelled 14 Freedom Riders after they were arrested in Jackson, Mississippi and jailed in Parchman state prison. The students successfully sued Tennessee A & I and several returned to graduate. By contrast, Halberstam (Reference Halberstam1998: 60–76) maintains that both Fisk and American Baptist Seminary were centers of political and cultural activity that tended to attract mission-driven students, including White exchange students at Fisk.

Nonetheless, the channeling of mission-driven students through private historically Black colleges into the Lawson workshops was not an absolute pattern. A & I students, who had often grown up in Nashville, found their way through Nashville student networks to the Lawson workshops. A career-driven student, Curtis Murphy (Reference Murphy2009), for example, had enrolled at Tennessee A & I with strong family encouragement to pursue an engineering career. He had little awareness of the civil rights movement, was informed of the Lawson workshops by his college roommate who was Lawson’s brother-in-law, and, overcoming his initial skepticism of nonviolence, became an active participant and recruiter of A & I students for the Lawson workshops and the Nashville movement (Halberstam Reference Halberstam1998: 149–63; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012). What is more, several of the Freedom Riders who were expelled from Tennessee A & I in 1961, including Catherine Burks Brooks (Reference Brooks2009), Bill Harbor (Reference Harbor2009), Pauline Knight (Reference Knight2009), and Rip Patton (Reference Patton2008), had participated in the Lawson workshops. The example of these students hints at an alternative to the pattern of non-Nashvillians who reported prior politicization and attended Nashville’s private Black colleges enrolling in Lawson’s workshops: namely, some Black students even at public institutions such as Tennessee A & I would be motivated to join Lawson’s workshop given their race, that is, for solidaristic reasons. Indeed, scholars (e.g., Irons Reference Irons1998; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2020; McAdam Reference McAdam1988) have shown that movement participatory structures are often structured by race.

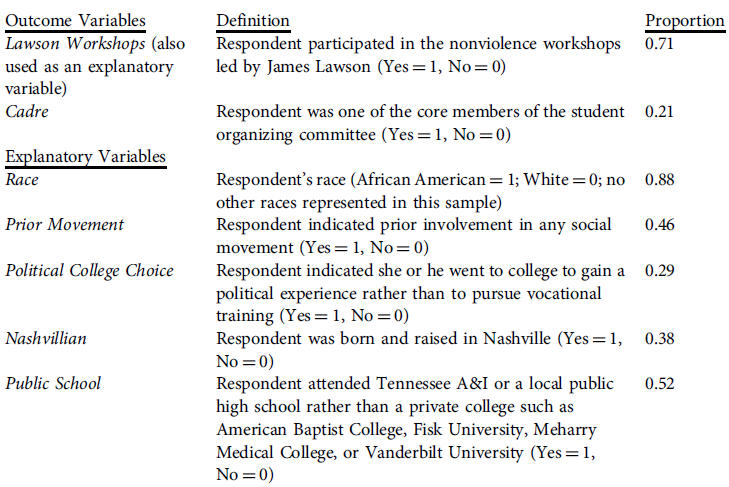

To assess how these characteristics of the college-student activists might, in addition to students’ race, combine to contribute to students’ decisions to participate in the Lawson workshops and, later, to serve in the core cadre of the Nashville movement, we apply the techniques of crisp-set Qualitative Comparison Analysis (QCA) to a subsample of 24 student participants in the Nashville civil rights movement included in our oral history data (i.e., excluding from this analysis 12 additional adult participants who also played support roles in the movement).Footnote 2 We constructed four explanatory variables for characteristics of students who might be expected to be resistant to adult movement planning—birthplace outside of Nashville, prior movement experience, political reasons for attending college, and attendance at a private Black college or university—and a fifth explanatory variable for race, and we apply QCA techniques to understand how these are linked to our outcome variables of interest, participation in the Lawson workshops and membership in the core cadre of the Nashville movement. The Appendix provides variable definitions and descriptive statistics.

QCA is a valuable method for this analysis in part because we are analyzing a sample of 24 respondents; although methods such as binary logistic regression would require larger sample sizes, QCA is ideal for small-n samples (Ragin Reference Ragin1987). Importantly, QCA also allows us to theorize and understand multiple conjunctional causation, that is, to identify multiple pathways (composed of multiple conditions) to career outcomes. In this case, we have theorized that students regardless of race might find themselves in the Lawson workshops if they grew up outside Nashville, reported an early history of activism, and attended a private university in Nashville for political reasons, but we also expect that some Black students might join the Lawson workshops for solidaristic reasons despite lacking such characteristics. A limitation of QCA is that analyses become unwieldy when a large number of variables are included, so following the recommendations of QCA methodologists, we limit our analyses to five-to-six variables (Amenta and Poulsen Reference Amenta and Poulsen1994: 23).

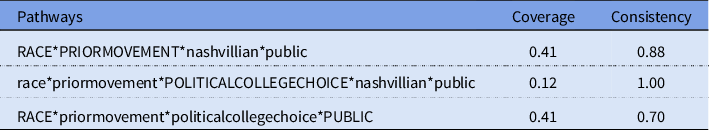

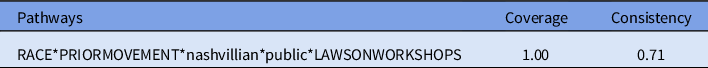

Table 2 provides the QCA results for pathways into the Lawson workshops. Seventeen of the 24 students in our sample found their way into the Lawson workshops, and they did so along three paths. Two of the three paths include highly politicized students who we might assume to be resistant to participation in an adult-planned movement: in the first pathway, Black students who were born outside Nashville, attended one of Nashville’s private colleges or universities, and reported prior movement experience joined the Lawson workshops. This pathway does not include political motivation for attending their college, which was not a necessary condition for their participation in the workshops. In a second pathway, White students who were born outside Nashville, did not report prior movement experience, but did report a political motivation for attending their private college or university, joined the Lawson workshops. This is, in effect, the pathway followed by White exchange students at private Black colleges and universities. The final pathway shows that Black students who lacked prior movement experience and who did not have a political motive for attending their public school, typically Tennessee A & I (but also majority-Black public high schools in the area), joined the Lawson workshops. Overall, a slight majority of the student Lawson-workshop participants in the sample (9 of 17, or 53 percent) exhibit characteristics of students we might expect to resist participation in an adult-planned movement.

Table 2. QCA results for pathways into the Lawson workshops

Note: N = 24. The results indicate the combinations of explanatory conditions that are “necessary” for structuring pathways into modes of participation. Capitalized variables imply presence of condition is necessary for a mode of movement participation, and lowercased variables imply absence of condition is necessary for mode of movement participation. When variables are combined by * (read: “and”), this means that their joint combination is part of the pathway. Solution consistency indicates the degree to which cases with the set of causal conditions form a subset of the cases for the outcome of interest, and yield a gauge of goodness-of-fit; solution coverage indicates the degree of agreement between cases with the outcome of interest and cases with the causal combination(s), providing the percent of outcome accounted for by the causal combinations (Ragin Reference Ragin2008).

Table 3 assesses pathways into the “core cadre” of the Nashville movement. For this analysis, we include the five aforementioned explanatory variables and add participation in the Lawson workshops as a sixth explanatory variable. Five students in our sample (Marion Barry, Bernard Lafayette, James Lawson, John Lewis, and CT Vivian) were part of this core cadre. We find that all five students traveled the same pathway into the core cadre: all five were Black students who were born outside Nashville, reported prior movement experience, attended a private college or university, and participated in the Lawson workshops. In other words, all eventual members of the core cadre reflect the characteristics of students whom we might expect to be resistant to participation in a movement planned by the older SCLC generation (with only a political consideration for attending college being an unnecessary condition for membership in the core cadre).

Table 3. QCA results for pathways into the core cadre of the Nashville movement

Note: N = 24. Capitalized variables imply that the presence of a condition is necessary to explain an outcome; lowercase variables imply that the absence of condition is necessary to explain an outcome; and the absence of a variable implies that the presence or absence of that condition is not necessary to explain an outcome.

Accounting for Students’ Participation in an Adult-Planned Movement

The question thus remains: Why were these students willing to participate in the adult-planned Nashville movement? Building on the insights of Robnett (Reference Robnett1996), we argue that “bridge leaders” served as intermediaries between these student activists and the leaders of formal civil rights organizations and thus bridged the age divides between these students and the more senior adults. In particular, James Lawson would serve as the intermediary between the three generations of nonviolent activists (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016). Through our interviews, we found that it was not the case that James Lawson personally recruited students to participate in his workshops as well as the subsequent sit-ins. Rather, most of the students in our study were personally recruited by other students, especially John Lewis (who personally recruited 9 of the 24 student respondents). Yet Lawson would fill a “structural hole” (Burt Reference Burt1992) between the students and the adult-led NCLC once those students arrived in his workshops. Lawson convinced the students to take up the NCLC’s formulated goal of desegregating downtown Nashville, as it aligned with the students’ own desires to work to end Jim Crow in the South. Lawson’s workshops, housed in the basement of Clark Memorial United Methodist Church, inculcated the importance of nonviolence and allowed students to role-play participation in sit-ins, the tactic NCLC adult workshop participants had agreed upon.

Why were students so drawn to Lawson, who had been recruited to Nashville by more senior civil rights leaders? In terms of microstructural characteristics, two attributes positioned him to appeal both to the younger students and the more senior civil rights leaders. First, his age: Lawson was slightly older than most of the students who would participate in the Nashville sit-ins, yet younger than most of the established civil rights leaders in Nashville. Born in 1928, Lawson turned 31 in Reference Lawson1959, when he began organizing the nonviolence workshops. Second, his dual position as both a student and a religious leader in Nashville: as a student at Vanderbilt’s Divinity School and as an organizer for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Lawson could simultaneously relate to the experiences of other students and the more established civil rights leaders in Nashville. Lawson was not asking students in his nonviolence workshops to take risks he was not willing to assume. Indeed, Lawson would be expelled from Vanderbilt’s Divinity School and arrested in 1960 due to his involvement in the civil rights movement.

Still, it is not the case that any person of Lawson’s age and dual student-worker status would have been able to bridge age divides within the Nashville civil rights movement. Culturally, Lawson was also ideally suited to bridge divides between students and the more senior movement leaders given his deep familiarity with the students’ own religious traditions. As the son of the pastor of an African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, Lawson was deeply immersed in the Black church at an early age. After working in India as a chaplain for Hislop College between 1953 to 1956, he similarly became immersed in Gandhian nonviolent praxis. Arriving in Nashville in 1958 as the Southern field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and soon organizing nonviolence workshops for adult community members and then students, Lawson was uniquely positioned to relate biblical insights considering nonviolent praxis, engaging in a process Snarr (Reference Snarr2009) labels “ideology translation.” As Lawson (Reference Lawson2009) reflected:

[T]o me it was more of the radical character of the intellectual and spiritual and behavioral work of Jesus of Nazareth that had impacted me…. This is important for another reason because while I was back then often called a Gandhian by people in the press especially in history, I was a Gandhian only in the sense that he experimented with nonviolence, introduced the word in the 20th century, coined the word “soul-force” in the 20th century, early 20th century, and this was all a part of the explosion of knowledge in the 20th century, only this aspect of that was largely unacceptable…. In the workshops this was very important because I started out by reinterpreting the Bible in the light of the ideas of Jesus. So I rooted the philosophical, theological, spiritual foundations of what we did in Christian baptism and in Jesus. I mean I deliberately did that because most of the folk in the rooms where I taught around the South were members of the churches so I took our Christian roots and reinterpreted it in the light of nonviolence. Martin King later said that, something like Gandhi provided the method and Christ provided the spirit.

Lawson’s approach deeply resonated with many of the student workshop participants. For example, in a conversation with James Lawson in Reference Lawson2009, student workshop participant Pauline Knight (Reference Knight2009) reflected:

PK: It’s been a great concern of mine that the fact that all of these people, everybody that I participated with, loves the Bible stories as much as I do, and I think that that’s left out too much. That we did have models of excellence in the person of Jesus the Christ. Whether anybody wants to hear that or not I can understand it, but they ought to know that that’s what we believed….

JL: I used Jesus as the model for nonviolence in my teaching.

PK: See, I was taught by you, wasn’t I?

JL: From day one, and that is left out of all the books.

The result of the sit-ins of the 1959–61 period, according to the Nashville Christian Leadership Council (1961: 3–4), was the complete desegregation of the downtown department stores and movie theaters; the promotion of two Black police officers; the desegregation of Fair Park by County Judge Beverly Briley; several African Americans being employed in white-collar jobs formerly held by Whites; and NCLC activists completing the CORE Freedom Rides that had been disrupted in Alabama. “With these and other activities,” the NCLC proclaimed, “the Nashville Christian Leadership Council has assumed a place of real leadership in the entire area of human rights” (ibid.: 4). Furthermore, emerging from the Nashville movement was one of the most impressive groups of student activists ever to emerge out of a movement center (Carson Reference Carson1981; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016; Isaac Reference Isaac and Hank2019). As Lawson (Reference Lawson2007) remarked:

I suppose you have to say that this was an unusual gathering of people and C.T. and I talked about this [recently] … that there was no way for it to be accidental, that coming to Nashville in ’58 was a joining of people like many of the ones I’ve named. How could that be? I do not think there is a single place there was a movement that that array of people were involved who then continued to carry the banner in the 60s and the 70s and beyond. Bernard Lafayette became an American Friend Service committeeperson, the organizer in Selma, Alabama, and eventually an SCLC staff member. Diane Nash and Jim Bevel after ’61 decided to give some attention to helping break the barriers in Mississippi for organization. Marion Berry organized his own group of young people in Washington, D.C. that was the foundation for his becoming mayor. It was very effective stuff…. John Lewis became SNCC chair all across the south, voting registration leader, and so forth. Bernard Lafayette eventually becomes a trainer and teacher of nonviolence.… There’s an astonishing group of people who became essentially a part of the new humanity while we were here. No matter what our impulses were before that, this dramatized it for us and John Lewis has made it so very powerful, we became a beloved community. And of course that’s one of my theories of nonviolence, which I did inherit from Gandhi. Namely that the movement becomes the kind of community it’s hoping to see the society become. That in the process of working on the struggle it becomes a kind of a model for the future.

Discussion

The case of the 1960s-era, nonviolent Nashville civil rights movement illuminates a new model of intergenerational movement mobilization and its role in the dialogical diffusion of a movement praxis. At this pivotal historical moment, in which the US civil rights movement was shifting its tactical course from NAACP-led litigation toward SCLC-led nonviolent direct action, the SCLC—with the bridging leadership of James Lawson—linked three activist age generations in a three-stage mobilization and dialogical diffusion of this new Gandhian praxis and tactical turn in the civil rights movement. The three-stage model of intergenerational movement mobilization comprises the stages of (1) “site selection,” (2) “tactical design,” and (3) “biographical convergence.” The three stages, in the Nashville case, were carried out by three activist age generations, namely, the oldest “pacifism-nonviolence” generation, the “SCLC generation,” and the youngest “SNCC generation,” respectively and collaboratively.

Intergenerational mobilization and collaboration were crucial to implementing the “collective learning” entailed in the dialogical diffusion of the new movement praxis (Chabot Reference Chabot2012), that is, Gandhian nonviolence. At the time, this praxis was “new” in two respects. First, the praxis originated in India and had only recently entered into the US cultural repertoire of contentious tactics and action. Second, the tactic had only recently been adopted by US civil rights activists. Consequently, intergenerational mentoring in the new praxis was at the heart of the collective-learning process in the dialogical diffusion of nonviolence praxis: that is, the pacifism-nonviolence generation translated Gandhian nonviolence for Western deployment and mentored the SCLC generation in the praxis, and the SCLC generation mentored the SNCC generation, especially in the formation of the Nashville core cadre, who went on to practice and diffuse nonviolence praxis and direct action to dismantle Jim Crow throughout the US South and beyond (Cornfield et al. Reference Cornfield2019; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016, Reference Isaac and Hank2020).

The Reverend James M. Lawson Jr. was the central “bridge leader” in the intergenerational mobilization process. His centrality in bridging activist age-generations stemmed from his centrality in intergenerational mentoring in nonviolence praxis. A member of the middle SCLC generation, Lawson was mentored by members of the older pacifism-nonviolence generation, especially A. J. Muste of the Fellowship of Reconciliation; and, at the invitation and behest of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Lawson, in turn, went on to mentor not only his cohort of SCLC activists but also the youngest SNCC generation, especially the Nashville core cadre by way of his legendary Nashville nonviolence workshops.

Several historical, biographical, demographic, and spatial factors facilitated the Nashville-derived three-stage intergenerational mobilization model. First, the model emerges at an important historical moment—the civil rights movement’s tactical turn toward nonviolence, a turn toward a new tactic that required collective learning to be sustained and deployed in the United States. Intergenerational mentoring in the new praxis produced the requisite collective learning for the dialogical diffusion of this new movement praxis. Second, Lawson’s biographical availability as a bridge leader was crucial for carrying out the process of collective learning and, therefore, deployment of the new praxis. A member of the middle generation of activists, Lawson possessed the expertise, and certainly the devotion, to the new praxis he had gained in part from the oldest generation of activists, as well as a manifest devotion to a religious theology he shared with the youngest activist generation. Third, the dramatic post–World War II surge in US college enrollments, and in the population of politicized Black and White college students, during this period of national civil rights movement protest and mobilization was an important demographic trend that greatly increased the national pool of “biographically available” activists who would engage in nonviolent direct action. Finally, in light of the “multicity” SCLC strategy of coordinating a series of protest centers, the biographical availability of the growing pool of college-student activists was enhanced by their spatial distribution and dense concentration in university cities like Nashville that facilitated implementation of local nonviolent direct actions.

Conclusion

Our three-stage, intergenerational model of movement mobilization, derived from the case of the 1960s-era, nonviolent Nashville civil rights movement, suggests a research agenda on the sustainability and generalizability of the model in processes of dialogical diffusion of movement praxes. Future research on the sustainability and generalizability of intergenerational mobilization can be informed by three dimensions of the Nashville case: (1) the historical moment in the tactical course of a movement; (2) bridging leadership, especially the bridge leader as a lynchpin in an intergenerational mentoring process; and (3) demographic trends and spatial distributions of the pool of biographically available prospective activists.

First, in the Nashville case, intergenerational mobilization was initiated during a pivotal historical moment in the tactical course of the US civil rights movement. From a “tactical adaptation” perspective (Blee Reference Blee2012; Isaac Reference Isaac and Hank2019; McAdam Reference McAdam1983; McCammon Reference McCammon2012), the Nashville movement and model were the vehicle for the deployment and dialogical diffusion of a new movement praxis—that is, Gandhian nonviolent direct action—that the movement adopted as its existing praxis of legal litigation encountered resistance in its implementation and enforcement in the United States. The newness of the new praxis in the US cultural and tactical repertoire of contention compelled the senior movement activists to mentor the growing youth movement, often skeptical of the new praxis, in the new praxis (Becker Reference Becker, Powell and Richard1984; Coley Reference Coley2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Thomas2017; Frenette Reference Frenette2019; Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Lowell2018). This suggests that the Nashville model of intergenerational mobilization occurs during those pivotal historical moments in the tactical course of a movement requiring intergenerational mentoring in a new movement praxis, what Chabot (Reference Chabot2012) terms the translation and experimentation stages of collective learning in the dialogical diffusion of a movement praxis; and, that intergenerational mobilization is less likely to occur when youth movements abandon new praxes imparted by senior activists that reach a point of diminishing returns in their implementation stage of dialogical diffusion (Becker Reference Becker, Powell and Richard1984; Chabot Reference Chabot2012; Coley Reference Coley2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Thomas2017; Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Lowell2018).

Second, Lawson, as bridge leader, possessed the requisite knowledge and expertise for intergenerational mentoring. A member of the middle, activist generation in the tripartite set of activist generations of the Nashville movement, Lawson was mentored in nonviolence praxis by the oldest activist generation; had become a nationally recognized adherent and expert in nonviolence; and mentored the youngest activist generation in the praxis. What is more, his adherence to a Judeo-Christian theology he shared with the youngest generation allowed him to “translate” the new praxis, as Chabot (Reference Chabot2012) puts it, and mentor the youngest generation in terms familiar to his mentees in the nonviolence workshops. This suggests that the Nashville intergenerational model depends for its implementation on effective intergenerational bridging and mentoring that translate and diffuse a new praxis in terms that are familiar to an otherwise skeptical youth movement; and that the intergenerational model will founder on the shoals of ineffective bridging leadership in persuading a youth movement to adopt a new praxis (Becker Reference Becker, Powell and Richard1984; Coley Reference Coley2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Thomas2017; Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Lowell2018).

Finally, the Nashville model thrived in demographic and spatial conditions that encouraged collective learning and the biographical availability of prospective activists. The tactical turn toward nonviolence in the movement coincided with the dramatic surge in college enrollments and the dense concentration of “biographically available” college students in US university cities. In Nashville, all three generations of activists—the oldest, middle, and (large) youngest generations—participated simultaneously and in the same space in mastering, applying, and diffusing the new praxis. What is more, all three generations collaborated in the ongoing, iterative, dialogical process of translating, experimenting, and implementing the new praxis (Chabot Reference Chabot2012). Indeed, the Nashville core cadre of the youngest activist generation went on to mentor and expand itself in nonviolence not only in Nashville, but throughout the US South and beyond (Cornfield et al. Reference Cornfield2019; Isaac Reference Isaac and Hank2019; Isaac et al. Reference Isaac and Hank2012, Reference Isaac and Hank2016). This suggests that the Nashville model is sustained by demographic and spatial conditions that encourage collective learning among a large, age-diverse, and densely settled pool of biographically available activists; and that the model is less sustainable under conditions that atomize and diminish the size of the pool of biographically available, prospective activists.

The research agenda on the sustainability and generalizability of the Nashville model is best conducted with comparative research designs. Comparative social movement research can thereby contribute to our sociological understanding of the conditions that influence intergenerational mentoring and mobilization and, therefore, the contextual and bridging factors that encourage the dialogical diffusion of movement praxes.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all interviewees, veterans of the Southern civil rights movement, who gave so generously of their time and knowledge of “the movement.” Without them, so much would have been impossible including this project. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Vanderbilt Center for Nashville Studies, Vanderbilt University College of Arts and Science, the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt endowment, and Vanderbilt Commons. We thank the following people who played important roles in the project: Kathy Conkwright and Rosevelt Noble (videography); Cathy Kaiser (interview transcription); Stephanie Pruitt (Center for Nashville Studies, Vanderbilt University); students in several Vanderbilt University seminars and Shai Dromi for helpful feedback; and George Becker, Amanda Brockman, Dasom Lee, Frank Lester, and Pamela Morgan for helpful bibliographic assistance.

Appendix: Variable Definitions and Descriptive Statistics