What is Known About this Topic?

Victims of IPVAW frequently go to healthcare centers with a covert reason and symptoms that are difficult to filter for diagnosis.

PCPs are in a privileged position to detect IPVAW from healthcare centers.

In Spain, protocols are available for detecting and attending IPVAW from healthcare centers.

What Does this Paper Add?

In general, protocols to attend IPVAW from healthcare centers in Spain show homogeneity. However, they are insufficient to adequately respond to the problem, requiring a greater commitment of the health system. Policy decisions under this strategy create a framework of hope and social confidence that the problem is being adequately responded to when it is not.

PCPs reported obstacles to attend IPVAW in consultation such as lack of time and training in IPVAW, feelings of fear, frustration, or impotence, as well as cultural, educational and political factors.

It is required to train PCPs to apply protocols to attend IPVAW from healthcare centers as well as in understanding the psychological process of victims to accompany them and avoid discomfort among PCP.

Intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) is a public health problem that involves physical, psychological, or sexual abuse, as well as controlling behaviors by a current or former intimate partner, affecting one in three women in their lifetime (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022). The consequences of IPVAW could be devastating to women’s physical and mental health, even after the abuse has ended, causing hematomas, fractures, chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety, among others (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; Ellsberg et al., Reference Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts and Garcia-Moreno2008; Sarasua et al., Reference Sarasua, Zubizarreta, Echeburúa and de Corral2007; Wang, Reference Wang2016). Consequently, victims of IPVAW tend to have worse general health than women who do not suffer it and frequently visit healthcare centers, requiring wide-ranging medical services (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; Taft et al., Reference Taft, O’Doherty, Hegarty, Ramsay, Davidson and Feder2013).

Healthcare centers can prevent, detect, and mitigate IPVAW, being the role of the primary care physician (PCP) crucial for it (Badenes-Sastre & Expósito, Reference Badenes-Sastre and Expósito2021; Fernández, Reference Fernández2015; Ruiz-Pérez et al., Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Blanco-Prieto and Vives-Cases2004). In this regard, IPVAW victims identify PCPs as referral professionals to disclose their situation (García-Moreno et al., 2014). However, in Spain, although most PCPs consider IPVAW a public health issue, their responses (e.g., injury reports) encompass only 9.6% of the total number of IPVAW complaints, reflecting the need for greater involvement in this issue (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, 2019; Lorente, Reference Lorente2020). The lack of time, knowledge, and training in IPVAW; fear of legal consequences; lack of practical and psychosocial skills for IPVAW interventions; or the lack of a clear role in addressing IPVAW could pose some obstacles for PCPs to address IPVAW (Fernández, Reference Fernández2015; García-Quinto et al., Reference García-Quinto, Briones-Vozmediano, Otero-García, Goicolea and Vives-Cases2022; Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2015). In this sense, it is necessary to examine the variables involved in PCPs’ responses to IPVAW to direct intervention and prevention efforts.

Advanced policies have been supported to facilitate the approach to IPVAW in the health care sector in Spain. Specifically, Ley Orgánica 1/2004 established measures of awareness and intervention for early detection of IPVAW and women’s care in the health care sector, as well as the implementation of protocols to attend IPVAW. Consequently, national and autonomic protocols were developed in Spain as fundamental tools to respond to IPVAW from the health care perspective. The first national protocol was published in 2007 by the Spanish Gender Violence Commission of the Council, considering the advice of numerous experts in the field. It also formed the reference for the rest of the autonomic protocols, and this version was upgraded in 2012 (Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2012). Likewise, the WHO (2013) developed a reference guide entitled “Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women. WHO clinical and policy guidelines” that includes evidence-based recommendations to improve IPVAW response from healthcare centers. In this sense, to ensure an adequate approach to mitigating IPVAW from healthcare centers, Spanish protocols should comply with these recommendations.

Protocols should define and systematize detection and intervention actions from healthcare centers, but they should also be practical and useful to PCPs (Fernández, Reference Fernández2015). Despite this knowledge, no studies have synthetized and analyzed the procedure described in the protocols, including Spanish PCPs’ perspectives. To address this gap, the purpose of this study was to explore how healthcare centers in Spain address IPVAW. The work was conducted in two studies. Study 1 involved examining the protocols available in Spain via autonomous communities to check their homogeneity and whether they comply with the WHO guidelines. In Study 2, a focus group explored PCPs’ perspectives on (a) their role in addressing IPVAW, (b) the use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to address IPVAW, (c) their experiences in IPVAW care, and (d) the obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultations.

Study 1

Method

A comprehensive search was done using the reference website of the Spanish government’s Ministerio de Salud y Ministerio de Igualdad to locate the protocols relevant to attending IPVAW victims in healthcare centers in Spain, as well as in each autonomous community. The protocols were included if they (a) provide information for health professionals to address IPVAW in healthcare centers and (b) were the latest version available. Lastly, 18 protocols were included in the study, one national and one per autonomous community. Ceuta and Melilla were not incorporated because they do not have autonomic protocols; theirs are based on the general protocol in Spain.

Data Extraction and Analysis

A coding protocol was developed to determine if the Spanish protocols to address IPVAW in healthcare centers were in accordance with WHO guidelines. To this end, two independent coders (M.B. and A.B.) conducted the data extraction, solving disagreements by discussion and, when required, through a consensus with a third researcher (F.E.).

Specifically, the WHO guidelines included six dimensions that were analyzed: (a) women-centered care, (b) identification and care for survivors of intimate partner violence, (c) clinical care for survivors of sexual assault, (d) training of health care professionals on intimate partner violence and sexual violence, (e) health care policy and provision, and (f) mandatory reporting of intimate partner violence. The process used in the development of these guidelines is outlined in the WHO handbook for guideline development (WHO, 2010). Additionally, the Spanish protocol to address IPVAW in healthcare centers points out that it is essential to include information on the detection, risk assessment, and prevention of IPVAW (Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2012). Therefore, in the present study, the six dimensions described by the WHO guidelines and the detection, risk assessment, and IPVAW intervention sections included in the Spanish reference protocol were analyzed.

Extracted data included protocol title, autonomous community of destination, year of publication (last version), the six WHO guideline dimensions, detection procedure, risk assessment, and intervention. Lastly, the percentage of intercoder agreement was calculated, and data registered were analyzed according to whether the protocols complied with WHO guidelines, summarizing each recommendation.

Results

Initially, a kappa coefficient was calculated to determine agreement between coders. According to Fleiss (Reference Fleiss2000), a very good intercoder reliability was obtained (0.8–1.0). Specifically, the first and second coders showed a high level of agreement for the inclusion of protocols (κ = 0.94) and data registered about the compliance or noncompliance with the six dimensions of the WHO guidelines, as well as the detection, assessment, and intervention sections for the 18 protocols assessed (κ > 0.85).

Table 1 contains the main characteristics of the protocols included in the study. The protocols’ years of publication ranged from 2003 to 2020, 22.22% of them having been published in the last 5 years of the review. The autonomous community of Navarra had interdisciplinary coordination protocols, but it did not have a specific protocol to attend IPVAW victims in healthcare centers. The Galician protocol was also included in the analysis, despite not being available in Spanish.

Table 1. Main Characteristics of the Protocols to Attend IPVAW in Spain

Note. IPVAW = Intimate partner violence against women; * = Cantabria published updated protocol only for sexual assaults in 2017; Castile-LaMancha published a general guide intended for all types of professionals in 2009; Valencian Community published updated protocol only for emergencies in 2020.

Regarding the WHO guidelines, six dimensions were required in any protocol to address IPVAW in healthcare centers: (a) women-centered care, (b) identification and care for survivors of intimate partner violence, (c) clinical care for survivors of sexual assault, (d) training of health care providers on intimate partner violence and sexual violence, (e) health care policy and provision, and (f) mandatory reporting of intimate partner violence.

Women-Centered Care

Immediate support for women reporting IPVAW should be offered. Among the indications for health professionals, they must (a) maintain an active listening attitude without prejudice and validate the woman’s feelings, (b) explore the victim’s background of violence, (c) provide information about useful recourses to approach violence (e.g., legal services), (d) help women to increase their safety, and (e) promote social support. Additionally, a private space and guarantee of confidentiality are required.

All the autonomous communities included some indications about women-centered care, such as recourses to address IPVAW (e.g., call center services, websites, or specialized centers), information about signs and symptoms of IPVAW, examples of questions to ask women in consultation, and examples of documents to report situations of IPVAW. It is noteworthy that the Balearic Islands protocol (Direcció General Salut Pública i Participació i Conselleria Salut, 2017), Extremadura protocol (Servicio Extremeño de Salud, 2016), or La Rioja protocol (Consejería de Salud del Gobierno de la Rioja, 2010), are complete because, among other reasons, they offer action plans according to the specific situation (e.g., whether the woman recognizes that she is suffering from IPVAW) or include most of the information in a single document. Other protocols, such as those from Aragon (Gobierno de Aragón, Departamento de Salud y Consumo, 2005) or Castile and Leon (Consejería de Sanidad de Junta de Castilla y León, 2019), are focused on how to work with women according to their stage of motivation to change. However, the Navarra protocol (Nafarroako Berdintasunareko Institutua, 2018) is incomplete and should be reviewed (e.g., it does not include examples of questions to ask IPVAW victims or documents to report it). Likewise, the Aragon protocol uses the term “domestic violence” to refer to IPVAW as defined in the Ley Orgánica 1/2004. In this sense, although the phenomenon is also termed “domestic violence” in other countries, it could lead to confusion in Spain.

Identification and Care for Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence

Detecting and responding to cases of IPVAW is necessary. Nevertheless, positions vary on the appropriateness of universal screening. Due to this controversy and based on previous scientific research, the WHO does not recommend implementing universal screening, except when there are indicators of suspected violence. The Andalusia and Basque Country protocols (Consejería de Salud y Familias de la Junta de Andalucía, 2020; Osakidetza Eusko Jaurlaritza, 2019), clarify the existence of this controversy in their recommendations, while the Aragon, Asturias (Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias, 2016), Castile-LaMancha (Dirección General de Salud Pública y Participación de la Consejería de Sanidad de Castilla La Mancha, 2005), Madrid (Servicio Madrileño de Salud, 2011), Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud, 2007), and Navarra protocols do not mention it. The rest of the protocols by autonomous communities recommend universal screening, possibly because they are based on the 2012 Spanish protocol reference. In this line, the Spanish protocol must be updated because it was published before the WHO guideline recommendations (WHO, 2013), based on previous WHO reports. In turn, all the protocols strongly recommend that women suspected of being abused be asked about IPVAW. Moreover, the protocols must integrate mental health care for women with mental disorders before addressing IPVAW or its consequences. Only a few protocols address these situations: Spanish, Andalusia, Asturias, Baelaric Islands, Basque Country, Canary Islands (Servicio Canario de la Salud de la Consejería de Sanidad y Consumo, 2003), Cantabria (Servicio Cántabro de Salud de la Consejería de Sanidad, 2007), Valencian Community (Agència Valenciana de Salut de la Consellería de Sanitat, 2009), Extremadura, Galicia (Servizo Galego de Saúde de la Consellería de Sanidade, 2009) and La Rioja protocols.

Concerning IPVAW interventions, it would be desirable for the protocols to indicate specific interventions depending on the situation (e.g., pregnant women or women in shelters). In general, all protocols include recommendations about the importance of intervening and attending to victims of IPVAW, as well as care for child victims of IPVAW. However, the psychotherapeutic intervention is not defined, except for in the protocol of the Balearic Islands, which includes treatments of choice according to the symptomatology (e.g., for posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing [EMDR] therapy is indicated).

Clinical Care for Survivors of Sexual Assault

Sexual assault is a potentially traumatic experience requiring acute and, at times, long-term care due to its negative consequences for women’s physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health. The WHO recommends offering first-line support to women survivors of sexual assault by any perpetrator, providing information and comfort to reduce women’s anxiety, helping victims connect to services and social support, offering practical care and support, and listening without pressuring or judging. All the protocols analyzed include these recommendations.

Another important point is avoiding the risk of unwanted pregnancy. In this regard, offering emergency contraception to survivors of sexual assault as soon as possible to maximize effectiveness was a strong recommendation by the WHO, and all the protocols analyzed include it. However, most of them do not indicate the type of medication and recommended dosage. The WHO recommends that healthcare professionals should offer a single 1.5-mg dose of Levonorgestrel (if available), because it is as effective as two doses of 0.75 mg given 12–24 hours apart. Nevertheless, only the Cantabria, Castile-LaMancha, Castile-Leon, Valencian Community, and Extremadura protocols specify this. Although the Basque Country protocol does not specifically indicate the use of Levonorgestrel, it includes a wide range of information on how to deal with various cases of sexual aggression, recommending similar pills such as Norgestrel.

As a result of sexual assault, women may contract sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV. Hence, some of the WHO’s recommendations include offering HIV post-exposure prophylaxis within 72 hours of a sexual assault and discussing HIV risk to determine the use of the prophylaxis. If a woman decides to use it, she should start the regimen as soon as possible (before 72 hours), receive testing and counselling at the initial consultation, adhere to counselling, and be provided medicaments and vaccines for Hepatitis B. All protocols provide information about these aspects at various levels of depth, except for those from the Balearic Islands and Canarias, which do not report any information about medical treatment (e.g., prophylaxis or vaccinations for Hepatitis B) recommended in cases of sexual assault as indicated by the WHO.

Additionally, some autonomous communities, such as the Balearic Islands, Cantabria, Catalonia, and Valencian Community, provide specific documents to address attending survivors of sexual assault in greater depth.

Training for Health Care Providers on Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence

Healthcare professionals should be prepared to care for victims of IPVAW and have basic knowledge about violence, existing services that might offer support to victims, inappropriate attitudes among healthcare professionals (e.g., blaming women for violence) their own experiences of IPVAW, and various aspects of responding to this problem (e.g., identification, safety assessment and planning, communication and clinical skills, documentation, and provision of referral pathways). The protocols analyzed align with WHO recommendations; they all reflect the importance of training health professionals in IPVAW. The protocols include examples of questions to ask women depending on their situation (e.g., suspected IPVAW, injuries, etc.). Additionally, if possible, the WHO recommends integrating all these aspects into existing health services rather than providing them as stand-alone services, given the overlap between IPVAW and sexual assault. However, this information is not included in most of the protocols, perhaps because it is understood that training healthcare professionals in IPVAW includes addressing physical as well as psychological and sexual violence.

Health Care Policy and Provision

IPVAW victims should obtain health care at any time they require it. The WHO guidelines state that a healthcare center should have a healthcare professional who is trained in IPVAW care and is always available. This point is very clear in all the protocols analyzed. To the extent possible, it is recommended that care for IPVAW victims be integrated into existing health services (not as separate services), prioritizing training and provision of services in primary care. These points are reflected in the development of protocols to respond to IPVAW in primary care, highlighting the importance of health professionals in the detection of and care for this problem. Conversely, the Navarra protocol does not comply with this recommendation. In fact, it is incomplete from the perspective of responding to IPVAW in health care facilities. On the contrary, it includes brief outlines on the actions to be taken in various areas (e.g., police or health).

Mandatory Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence

The WHO does not recommend that healthcare professionals report IPVAW to police unless provided by law. Reporting IPVAW is mandatory in Spain, having both positive and negative implications from the point of view of healthcare professionals and IPVAW victims. Hence, healthcare professionals need to understand their legal obligations (if any) and their professional codes of practice to ensure that women are informed fully about their choices and limitations of confidentiality. In this line, the analyzed protocols show clear and concrete information about mandatory reporting of intimate partner violence to the police by healthcare professionals (depending on the situation), as well as of child maltreatment and life-threatening incidents. Likewise, most of them include examples of documents for filling out injury reports or complaints.

Detection, Risk Assessment, and Intervention

The Spanish protocol to attend victims of IPVAW in healthcare centers includes detection, risk assessment, and intervention as three essential blocks to be addressed. Particularly, the section on detection includes (a) information about IPVAW (e.g., definition, consequences, or myths about violence among others), (b) indicators of suspicion of or vulnerability to IPVAW (e.g., anxiety or injuries), (c) instructions and examples on how to do an interview to identify IPVAW in case of suspicion (e.g., “Many times women who have problems like yours, such as [refer to some of the most significant ones] are experiencing some type of partner abuse. Does it happen to you?”), and (d) tips on what not to do during the interview and how to care for women (e.g., not to doubt the woman’s story).

Then, when professionals have the necessary information to take an active role in detecting IPVAW in consultation, an adequate risk assessment for women is necessary. In this regard, the risk assessment section contains information about how to (a) make a comprehensive assessment of the biopsychosocial factors, women’s situations, type of violence, safety, and danger (e.g., women’s coping strategies) and b) coordinate with other professional teams (e.g., social workers). Finally, the intervention section involves various forms of action (e.g., derivation or to report injuries) depending on the assessment previously carried out, considering the risk and awareness of the woman’s problem. Although the protocols differ in their levels of development and specification, all the autonomous communities address detection, risk assessment, and intervention in their protocols. Additionally, even though the protocols are focused on attending women from healthcare centers, they also provide guidelines for action in other settings such as emergency or specialized care services.

Study 2

Method

Design and Procedure

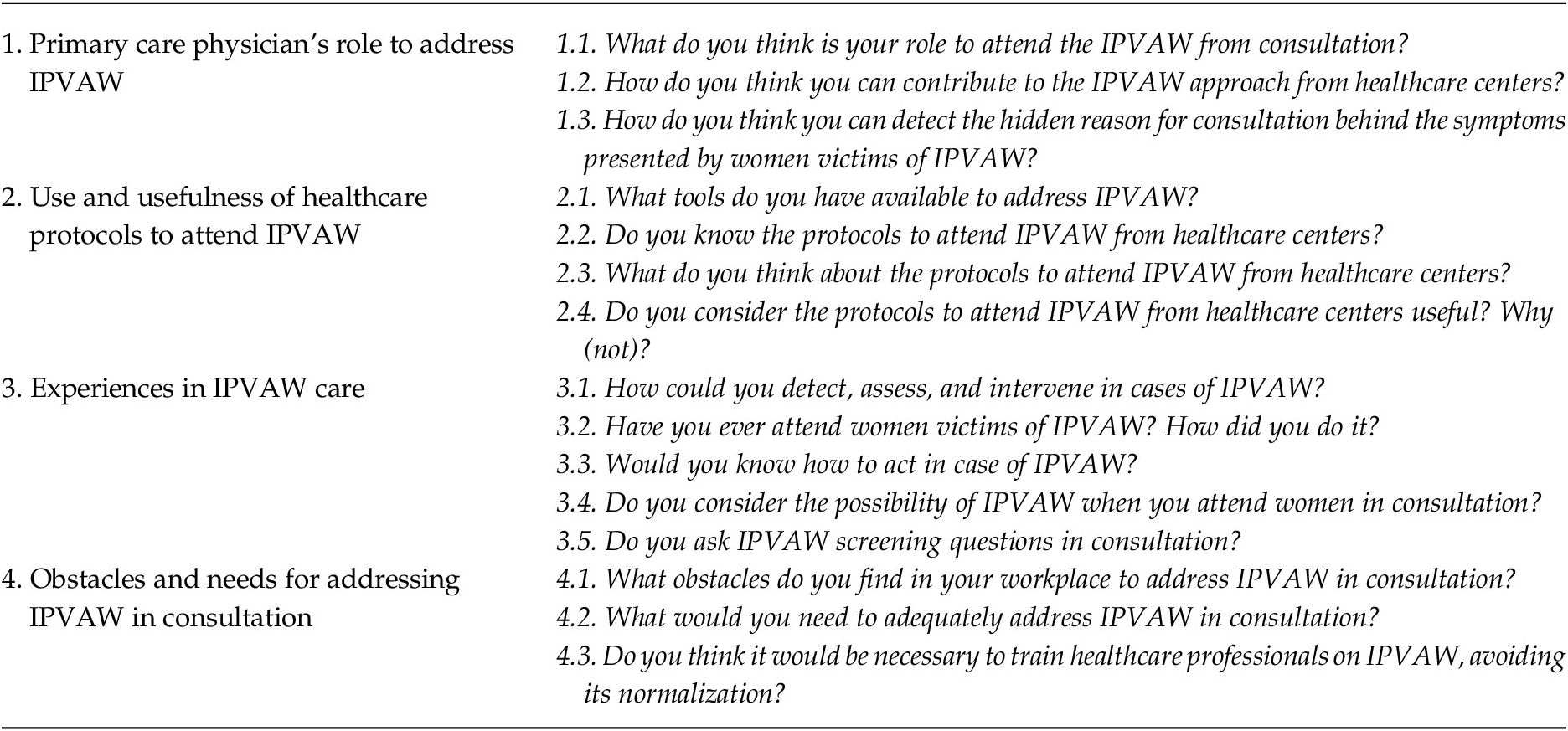

A qualitative study using an in-depth interview with a focus group was performed to explore PCPs’ perspectives on (a) their role in addressing IPVAW, (b) the use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to attend IPVAW victims, (c) their experiences in IPVAW care, and (d) the obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultation. Before data collection and analysis, the researchers carried out a reflexive dialogue to establish the categories to explore. Then, based on previous literature (Badenes-Sastre & Expósito, Reference Badenes-Sastre and Expósito2021; Coll-Vinent et al., Reference Coll-Vinent, Echeverría, Farràs, Rodríguez, Millá and Santiñà2008; Diéguez & Rodríguez Calvo, Reference Diéguez and Rodríguez2021; Fernández, Reference Fernández2015; González et al., Reference González, Durán Flores and González Rubio2019; Ruiz-Pérez et al., Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Blanco-Prieto and Vives-Cases2004; Saletti-Cuesta et al., Reference Saletti-Cuesta, Aizenberg and Ricci-Cabello2018; Taft et al., Reference Taft, O’Doherty, Hegarty, Ramsay, Davidson and Feder2013; Valdés et al., Reference Valdés, García and Sierra2016; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Halstead, Salani and Koermer2016), the objectives of the study were defined, including the research questions for the interview (see Table 2).

Table 2. Interview Questions for Focus Group

Note. IPVAW = Intimate partner violence against women.

The focus group interview was conducted after obtaining acceptance from the ethics committee of the University of Granada. Firstly, a message announcing the study was diffused by institutional mail and social networks to collect PCPs to participate in a focus group. PCPs interested in participating were called via the telephone numbers provided and were informed of the study’s objective and procedure, inviting them to enroll. Then, they signed informed consent according to the Helsinki Declaration, guaranteeing the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants’ data. No monetary incentives were provided for participation.

Lastly, the focus group interview was conducted online using the Google Meet application. A researcher (M.B.) moderated an interview about the participants’ perspectives on their role in addressing IPVAW, the use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to attend IPVAW, experiences in IPVAW care, and the obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultations. All the PCPs participated actively in the interview, which was video and audio recorded for subsequent transcription. To minimize the social desirability bias in qualitative research, the focus group interview was conducted according to the recommendations of Bergen and Labonté (Reference Bergen and Labonté2020).

Participants

A focus group is an appropriate method to collect information about attitudes, knowledge, and experiences in health care fields (Kitzinger, Reference Kitzinger1995; Myers, 1988; Nyumba et al., Reference Nyumba, Wilson, Derrick and Mukherjee2018). According to Myers’ recommendations (Reference Myers1998) for conducting focus groups, seven PCPs were selected via incidental sampling to participate. In this sense, previous studies (Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, de-León-de-León, Martin-de-las-Heras, Torres Cantero, Megías and Zapata-Calvente2022; Nyumba et al., Reference Nyumba, Wilson, Derrick and Mukherjee2018) support the use of a single focus group to conduct research.

The inclusion criterion for participation in the focus group was working as a PCP in the Spanish public health system. To recruit participants, a message was disseminated over the course of two months informing PCPs about the study through social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram) and institutional mail. Seven PCPs were willing to participate freely in the study, being informed of the research objectives and signing the informed consent according to the Helsinki Declaration. The confidentiality and anonymity of their answers were guaranteed, and no monetary incentives were provided for their participation. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the sample.

Table 3. Main Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

Note. IPVAW = intimate partner violence against women; M = man; W = woman; SD = Standard Deviation.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Granada. Before data collection and analysis, the researchers carried out a reflexive dialogue. Then, based on previous literature (Badenes-Sastre & Expósito, Reference Badenes-Sastre and Expósito2021; Coll-Vinent et al., Reference Coll-Vinent, Echeverría, Farràs, Rodríguez, Millá and Santiñà2008; Diéguez & Rodríguez, Reference Diéguez and Rodríguez2021; Fernández, Reference Fernández2015; González et al., Reference González, Durán Flores and González Rubio2019; Ruiz-Pérez et al., Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Blanco-Prieto and Vives-Cases2004; Saletti-Cuesta et al., Reference Saletti-Cuesta, Aizenberg and Ricci-Cabello2018; Siendones et al., Reference Siendones, Perea-Milla, Arjona, Agüera, Rubio and Molina2002; Taft et al., Reference Taft, O’Doherty, Hegarty, Ramsay, Davidson and Feder2013; Valdés et al., Reference Valdés, García and Sierra2016; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Halstead, Salani and Koermer2016), the objectives of the study and the research questions for the interview were set (see Table 2).

The focus group interview was conducted in December 2021, lasting 1 hour and 23 minutes. To obtain the data, the focus group was audio and video recorded with the participants’ consent and then transcribed into text. Then, according to previous literature (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Navarro-Carrillo et al., Reference Navarro-Carrillo, Beltrán-Morillas, Valor-Segura and Expósito2017; Zeighami et al., Reference Zeighami, Zakeri, Shahrbabaki and Dehghan2022), a content analysis was performed to explore PCPs’ perspectives on (a) their roles in addressing IPVAW, (b) the use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to attend IPVAW victims, (c) their experiences in IPVAW care, and (d) obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultations.

Two independent coders (M.B. and A.B.) encoded the citations of the participants in each category using the following procedure. Initially, they independently conducted a first reading of the interview transcript, and after that, the two coders independently encoded the citations of the participants in each category. Subsequently, the coders shared the coded citations for each category, indicating which citations were included and discussing discrepancies with a third coder. A kappa agreement index was obtained for the inclusion of citations in each category: (a) role in addressing IPVAW (κ = 1), (b) use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to attend IPVAW victims (κ = 0.87), (c) their experiences in IPVAW care (κ = 0.85), and (d) obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultation (κ = 0.81). Finally, discrepancies between the two coders regarding whether the protocols complied with the six dimensions of the WHO guidelines as well as the detection procedure, risk assessment, and intervention sections were discussed and resolved with the help of a third coder, resulting in full agreement to analyze the data found in this study.

Results

At the beginning of the interview, the participants introduced themselves, indicating their age, work position, years of work experience, and specific training in IPVAW (see Table 3). Then, information was obtained on the various research objectives (see Table 4). The main results showed that, although the use of healthcare protocols among PCPs was not so evident due to the lack of knowledge about their existence, localization, or practice, most participants considered their roles essential in attending to IPVAW victims (detecting and exploring the covert demand for consultation by victims) in healthcare centers. Additionally, from the PCPs’ perspective, the usefulness of the protocols was doubtful, and they acknowledged the controversy in the application of universal screening for IPVAW. PCPs recognized the need to depoliticize IPVAW and respond to victims, paying attention to indicators of abuse in women and not overlooking the issue. However, they admitted that victims of IPVAW are not always attended to as they should be. Lastly, PCPs indicated IPVAW training; the lack of time and coordinated multidisciplinary teams; cultural and educational factors; and the presence of feelings such as fear, frustration, or impotence as some of the main obstacles to addressing IPVAW.

Table 4. Primary Care Physicians Perspective on Research Objectives

Note. IPVAW = Intimate partner violence against women; PCP = Primary Care Physicians; P = participant; C = Citation.

Discussion

Having homogeneous tools and professionals trained to approach IPVAW in healthcare centers is essential for victims’ care. This study analyzed the available protocols in Spain, considering the WHO’s recommendations for attending IPVAW, the PCPs’ perspectives on the use and usefulness of these protocols, and the obstacles and requirements to respond to IPVAW adequately in consultations.

In general, national, and autonomic protocols in Spain were in accordance with WHO recommendations, showing homogeneity among them. However, it is insufficient to respond to IPVAW as a health problem; it is not enough to indicate what should be done. PCPs need to know how to respond appropriately to IPVAW. Otherwise, women may continue to be exposed to IPVAW, showing chronic physical and psychological symptomatology (Lorente, Reference Lorente2008; Reference Lorente2020).

All protocols encompassed the six main dimensions indicated in the WHO guideline to various extents (WHO, 2013), except in the community of Navarre, which includes several documents to address IPVAW but has no specific, detailed protocol for addressing IPVAW in health care centers. Additionally, controversy among protocols exists regarding universal screening. This controversy could be explained by the fact that the “Protocolo común para la actuación sanitaria ante la violencia de género [Spanish protocol to attend victims of IPVAW in healthcare centers] (2012)” recommended universal screening to all women in consultation, but the WHO (2013) stated that it should only be applied in cases of suspicion. The recommendation for universal screening depends on the guide on which the autonomic protocols have been based. In this regard, a proactive attitude is required to detect IPVAW and act accordingly, without waiting passively for the woman or the symptoms she presents to reveal that she is experiencing IPVAW.

Likewise, though the Aragon protocol (2005) defines various types of violence (e.g., in the family context or by the partner) correctly, it uses the term “domestic violence” to refer to any abuse by a partner or former partner. In the Spanish context, and in accordance with Ley Orgánica 1/2004 , the termFootnote 1 “gender violence” should be used, avoiding confusion due to the use of terms that refer to a different type of problem in Spain, which is not the objective of the protocols for addressing IPVAW in healthcare centers (Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2012). Finally, it is noteworthy that the national protocol has not been updated since 2012. In this regard, it would be advisable to consider updating it due to the evolution of IPVAW manifestations, for example, through new technologies (Sánchez-Hernández et al., Reference Sánchez-Hernández, Herrera-Enríquez and Expósito2020). Additionally, efforts to unify information on IPVAW reporting by PCPs are needed, considering WHO recommendations and Spanish legislation for PCPs, providing a clear idea of what their actions should be in the face of this problem.

Otherwise, the focus group allowed the researchers to explore the perspective of a PCP group on their roles in addressing IPVAW, the use and usefulness of healthcare protocols to attend IPVAW, their experiences in IPVAW care, and their perceptions about the obstacles to and requirements for addressing IPVAW in consultation. The participants’ discourse was consistent with previous literature (García-Díaz et al., Reference García-Díaz, Fernández-Feito, Bringas-Molleda, Rodríguez-Díaz and Lana2020) that pointed out that PCPs play an essential role in detecting and addressing IPVAW. IPVAW victims using healthcare centers share this view (Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2015). The participants agreed that their roles as healthcare professionals are fundamental to approach IPVAW (Footnote 2C1 P2, P2 C2). Particularly, as Participant 4 indicated (C3), IPVAW victims frequently go to healthcare centers with a covert reason for consultation, making PCPs’ essential to identifying the problem (Coll-Vinent et al., Reference Coll-Vinent, Echeverría, Farràs, Rodríguez, Millá and Santiñà2008; Ruiz-Pérez et al., Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Blanco-Prieto and Vives-Cases2004; WHO, 2022).

Regarding the use and usefulness of the protocols, their use among this group of PCPs is not so evident. Specifically, some participants reported a lack of knowledge about the existence of these protocols (P1 C4, P6 C5, P2 C6). Others, although they could recognize the protocols, did not know where to find and how to use them (P7 C7, P1 C8) or did not consider them practical (P4 C9). Consequently, to facilitate accessibility, information, and use of the protocols to address IPVAW, PCPs were informed about a mobile health app that guides PCPs and synthesizes the Andalusian protocol information, including a section for the general population; it can be used at the national level because it is based on the Spanish protocol to attend victims of IPVAW in healthcare centers (P2 C10, P4 C11). In this sense, the dissemination of updated information regarding the approach to IPVAW in healthcare centers will be key to offer an optimal response to victims. To this end, as established in the Ley Orgánica 1/2004 , implementing awareness-raising and continuing education programs among PCPs is required.

PCPs should adopt an attitude of alertness in consultations to identify IPVAW, because many medical consultations for women’s health problems are associated with its presence (Riggs et al., Reference Riggs, Caulfield and Street2000). In this regard, controversy exists regarding the application of universal screening for IPVAW in healthcare centers (Pichiule-Castañeda et al., Reference Pichiule-Castañeda, Gandarillas, Pires, Lasheras and Ordobás2020; Plazaola-Castaño et al., Reference Plazaola-Castaño, Ruiz-Pérez and Hernández-Torres2008; Taft et al., Reference Taft, O’Doherty, Hegarty, Ramsay, Davidson and Feder2013), also reflected in the participants’ perspectives (P3 C12, P7 C13, P1 C14). It seems surprising that, in the face of such a serious problem as IPVAW, one could consider adopting a passive attitude instead of being proactive, as in other types of health problems.

Further, when PCPs observe indicators of abuse in women, the problem should be addressed, and action in cases of suspected or confirmed IPVAW should not be restricted to reporting injuries. A comprehensive intervention should take place in which women are offered information and support, including follow-up to support victims’ full recovery (Diéguez & Rodríguez, Reference Diéguez and Rodríguez2021). Unfortunately, some PCPs still do not give the issue the attention it requires (P3 C18). Even if PCPs do not know how to address IPVAW, they must always respond to victims and not ignore the issue. In this sense, PCPs often ask social workers who are not recognized as health professionals for help (P2 C15, P4 C16, P7 C17), which, together with the lack of interdisciplinary teams, could affect the approach to IPVAW (García-Quinto et al., Reference García-Quinto, Briones-Vozmediano, Otero-García, Goicolea and Vives-Cases2022), requiring multidisciplinary teams (P5 C32).

It is worth highlighting the obstacles that this group of PCPs encounters in responding adequately to IPVAW in consultations. According to previous literature (Diéguez & Rodríguez, Reference Diéguez and Rodríguez2021; Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2015), IPVAW training, the lack of time and coordinated multidisciplinary teams, IPVAW normalization, or cultural and educational factors were some of the main obstacles mentioned by participants (P3 C19, P5 C20, P1 C21, P2 C22, P3 C23), requiring changes such as training teams of healthcare professionals with the knowledge and skills to respond to IPVAW effectively (Bacchus et al., Reference Bacchus, Mezey and Bewley2003; Waalen et al., Reference Waalen, Goodwin, Spitz, Petersen and Saltzman2000), so the normalization of IPVAW may determine the responses to this problem (Waltermaurer, Reference Waltermaurer2012). PCPs also expressed the need to depoliticize IPVAW (P2 C34), approaching IPVAW as what it is—a public health and social responsibility problem (WHO, 2022). In this respect, the health system should offer a strong, clear response to IPVAW, providing recourses (e.g., training, or multidisciplinary teams) to resolve the personal situation in each case.

Moreover, PCPs discussed feelings such as fear, frustration, or impotence as obstacles to addressing this problem (P1 C24, P2 C25, P4 C26, P7 C27, P3 C28, P1 C29, P2 C30, P4 C31). According to Participant 4 (C33), an adequate understanding of IPVAW as well as the internal and external barriers in which IPVAW victims are involved will be the first step in helping them (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002), and it could minimize PCPs’ emotional distress rooted in victims’ decisions. In turn, the impact of the obstacles (e.g., lack of training and multidisciplinary teams) on PCPs’ emotional responses may have a negative influence on their care for women suffering from IPVAW, requiring actions in this regard.

Concerning research implications, the researchers synthesized Spanish protocols’ content and analyzed their usefulness by conducting a focus group with PCPs. The obtained information provides a starting point for future research and contributes to advancing scientific knowledge on the approach to IPVAW in healthcare centers in Spain.

Greater efforts are needed to ensure the practical implementation of the Spanish protocols, considering their limitations and the main obstacles cited by this group of PCPs, such as lack of time and training in IPVAW; feelings of fear, frustration, or impotence; and cultural, educational, and political factors. In this regard, the health system needs to enable conditions for providers to address IPVAW, including good coordination, referral networks, or IPVAW training programs for PCPs, focusing on what puts victims at risk for IPVAW, how to approach it in a consultation, and where PCPs can access recourses to care for victims of IPVAW (García-Moreno et al., Reference García-Moreno, Hegarty, Lucas, Koziol-McLain, Colombini and Feder2014).

Specifically, training healthcare professionals in IPVAW to understand its origin and maintenance will be the first step to adopt a nonjudgmental attitude, avoiding the emergence of emotions such as fear, impotence, or frustration. For PCPs, these feelings could affect the quality of their interventions with IPVAW victims. Therefore, the need to establish self-care guidelines to reduce or prevent effects on these professionals’ health is important, which in turn would improve the quality of the intervention (Alonso-Ferres et al., Reference Alonso-Ferres, Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas, Expósito, Garrido-Macías, Herrera Enríquez, Herrera Enríquez, Ramírez Rubio, Ruiz-Muñoz, Sáez-Díaz, Sánchez-Hernández and Villanueva-Moya2022).

In addition to these aspects, it is vital to work on the beliefs and attitudes shown by PCPs, because IPVAW training alone could be insufficient to respond adequately to this problem. In particular, Badenes-Sastre et al. (Reference Badenes-Sastre, Lorente and Expósito2023) found that sexist ideology and favorable attitudes toward IPVAW influence future health professionals’ response to IPVAW cases. However, the training does not have a significant influence on willingness to intervene. In this sense, cultural, educational, and political factors may also hinder the response to IPVAW, requiring appropriate measures to address them.

To avoid normalization and passivity towards IPVAW, efforts should be directed toward educating about equality from an early age. It is necessary to create a more egalitarian society, which in turn translates into a proactive response to IPVAW from healthcare centers. Furthermore, during university training of health professionals, work should continue from a gender perspective and emphasize their roles in relation to IPVAW, thus creating professionals prepared to respond actively to cases of IPVAW.

Likewise, the problem of PCPs’ lack of time to detect and intervene in cases of IPVAW must be solved; otherwise, women will not receive the quality care they need. In this regard, organizational changes are required, reducing the number of patients to be attended by each professional and hiring more PCPs in primary care centers so that time can be dedicated to the detection of and intervention in IPVAW cases.

Regarding political implications, addressing IPVAW in healthcare centers should be a priority and not depend on the political party in power. All victims should be cared for equally, irrespective of the country or autonomous community in which they are located. As indicated by the WHO (2022), IPVAW is a global public health problem that affects women worldwide. In this sense, there have been social and legislative changes in Spain and internationally in relation to IPVAW (Ferrer-Pérez et al., Reference Ferrer-Pérez, Bosch-Fiol, Sánchez-Prada and Delgado-Álvarez2019). However, victims are still not offered optimal responses from healthcare centers. To this end, attention should be paid to preventing this issue, focusing on the influence of social and cultural factors in PCPs’ attitudes toward IPVAW and, consequently, their willingness to intervene in cases of IPVAW in consultation as a public health problem.

This study is subject to a few limitations worth noting. First, part of the analysis of the protocols is based on the recommendations from the WHO guidelines, but some of the protocols were developed before their publication and are based in the Spanish legislation (Ley Orgánica 1/2004), without considering the global recommendations (WHO, 2013). This limitation was considered in the discussion of the results. Second, the small sample size makes it difficult to generalize the results. Notwithstanding the relatively limited sample, this qualitative work was complemented by an exhaustive analysis of the content of the protocols, providing valuable insights into their adequacy to attend IPVAW victims in healthcare centers. Lastly, the type of analysis carried out only allowed descriptive conclusions. It would be convenient to carry out research that makes it possible to quantify the information obtained through the focus group and to symbolize the relationship between categories through networks of cooperation, as other qualitative studies do.

Future studies would be beneficial in terms of exploring how to minimize the obstacles PCPs encounter in implementing the protocols in consultation, considering healthcare centers’ perspectives, so the practical application of the contents of the protocols will be crucial. In this respect, it could be interesting to form more focus groups with PCPs who know and use these protocols to obtain more accurate information on the strengths and weaknesses of the tools available in Spain for attending IPVAW victims in health care centers.

Spanish protocols to address IPVAW in healthcare centers seem insufficient. Their use and practicality among PCPs are unclear, requiring training and specialization in the care of IPVAW victims. Participants considered that the practical application of these tools could be beneficial for attending IPVAW victims if the above-mentioned obstacles (e.g., lack of time, feelings toward victims, or IPVAW normalization) were addressed. In this sense, both promoting structural and organizational changes in healthcare centers, and training for PCPs in understanding IPVAW and the application of the protocols in consultations are needed to improve the care for victims.