Introduction

The title of this report is a question we are often asked, and ask ourselves, as social scientists using predominantly qualitative methods in an applied primary care research setting.Footnote 1 The value of qualitative research in policymaking, service development and practice in medicine, in the study of health service organisation and delivery, and in enhancing understanding of health, illness and ageing is increasingly recognised (Casebeer and Verhoef, Reference Casebeer and Verhoef1997; PLoS Medicine Editors, 2007; Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2015). However, our experience and that of colleagues suggest that it is still difficult to get this type of research reviewed by and published in journals where it will be read by health care practitioners.

A previous study (Gagliardi and Dobrow, Reference Gagliardi and Dobrow2011) found that (between 1999 and 2008) very few qualitative studies were published in high impact health, medical and policy journals, compared with non-qualitative studies. The authors suggested possible reasons for this that required further exploration, including editorial policy and practice, quality of submissions and reviewers’ understanding of how to assess qualitative research.

A 2015/16 ‘Twitterstorm’ over the British Medical Journal’s (BMJ) policy around qualitative research epitomised this struggle and led to over 80 academics submitting a letter to the BMJ inviting it to reconsider its policy (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh2016). It is not within the scope of this article to report the full content of the Twitter debate (see https://storify.com/shereebekker/bmjnoqual and https://twitter.com/hashtag/BMJnoqual?src=hash), but useful to include this extract from the BMJ editors’ response to Greenhalgh et al.’s letter:

‘Arguably, though, the ideal place for publication of many qualitative papers will be journals that are targeted at the specialist audience for whom the findings are especially pertinent. Important qualitative research of a highly specialist nature may actually be overlooked if published in a general medical journal’.

(Loder et al., Reference Loder, Groves, Schroter, Merino and Weber2016)

The numerous contributions to the online discussions about the BMJ’s publication policy indicate that these topics are increasingly being debated in academic communities. Nonetheless, while it is recognised that few qualitative studies are published in high impact health journals, much less is known about where health researchers do publish qualitative research. The BMJ is not alone in its policy – as Greenhalgh et al. (Reference Greenhalgh2016) point out, many leading US medical journals (such as the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Journal of Medicine) also consider qualitative research a low priority.

We therefore aimed to explore the question ‘Where does good quality health research using and exploring qualitative methods get published?’, focussing particularly on our own area of primary care.

Methods

Creating a database

We used a publically available database created as part of the Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014, a UK-based process of expert review, carried out in 36 subject-based Units of Assessment (UoAs). The results demonstrate the high quality and enhanced international standing of research conducted in UK universities. A submission comprises outputs, impact and environment: for our research we used outputs, defined as ‘the product of any form of research, published between January 2008 and December 2013’. Up to four outputs can be submitted for each member of staff that an institution enters into the process. This means that the outputs are considered by individuals and their institutions to be of good quality.

We used the Excel database on the REF website, searching the four UoAs that would include health research: clinical medicine (UoA1), primary care (UoA2), allied health care professionals (AHPs) (UoA3) and social policy (UoA22). We searched outputs using the following terms:

-

∙ ‘qualitative’ in article title or ‘qualitative’ in journal title

-

∙ any of the following terms in the article title: interview*, ethno*, experience*, focus group*, mixed method*, narrative*, photo*, video*.

These initial searches resulted in 1039 outputs (UoA1: 33/13 400; UoA2: 152/4881; UoA3: 542/10 358; UoA22: 312/4784) that were possibly qualitative research. While there were duplicates included in this figure, and not all of the outputs returned by the search were actually qualitative studies, these figures indicate that qualitative research represented around 3%, at most, of the total (33 423) REF submissions in the four UoAs.

Analysing the database

Using the database of 1039 articles, the two authors (J.C.R., J.L.) assessed each output to determine whether it could be defined as qualitative and had a main focus on health. If these characteristics were not clear from the title, each author looked at the abstract independently to make a decision. If there was no agreement, the full text was accessed in order to make a decision. On this basis we excluded articles that focussed on gambling, fostering, education, migration, social work practice, cell biology, sexuality (where not linked to health), smoke alarms, domestic violence, and reasons for alcohol and drug use, but made the decision to include articles focussing on public health.

Following exclusions on this basis, 567 articles remained (UoA1: 12/33; UoA2: 122/152; UoA3: 352/542; UoA22: 81/312); 24 of these were duplicates (due to being submitted to more than one UoA). Our final database therefore comprised 543 unique articles.

The authors categorised each article (independently, then though joint agreement) according to its methodological approach as follows:

-

(a) Qualitative methods: research conducted using only qualitative methods.

-

(b) Methodology: articles about how to do qualitative research, with the focus on methodology rather than findings.

-

(c) Mixed methods: including both quantitative and qualitative.

-

(d) Review or synthesis: which explicitly includes qualitative research articles.

Results

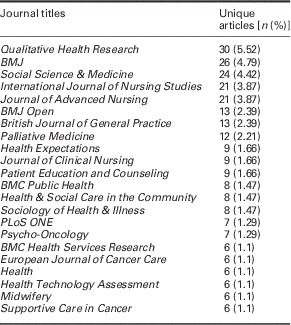

Table 1 illustrates the wide range of journals publishing good quality qualitative health research, and show that REF submissions included similar proportions of articles across social science health journals and other high impact health/medical journals. A high proportion of qualitative health articles submitted to REF 2014 were also published in nursing journals. Journals targeted at other specialist audiences and topics such as midwifery, cancer, health sociology and social care published fewer qualitative articles that were submitted to REF 2014.

Table 1 Journals with six or more qualitative health research articles entered in Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014

Table shows journals with six or more articles submitted to REF. In total, 184 journals included five or fewer articles that were submitted to REF 2014: six journals included five articles; six included four articles; 14 included three articles; 28 included two articles; 130 included one article.

Looking at publication title by UoA allows us to see further patterns (Table 2). UoA1 (medicine) included only 2% (n=12) of the REF qualitative health articles, in comparison with UoA22 (social policy) with 14% (n=81), UoA2 (primary care) with 22% (n=122) and the highest proportion of 62% (n=352) in UoA3 (AHPs).

Table 2 Research Excellence Framework 2014 qualitative health submissions according to Units of Assessment (UoAs) and publication journal

AHP=allied health care professionals.

Figures in brackets show the percentage within each UoA represented by that number of articles.

Total do not add up as the table does not show every journal.

Table shows journals with six or more articles submitted to REF. In total, 184 journals included five or fewer articles that were submitted to REF 2014: six journals included five articles; six included four articles; 14 included three articles; 28 included two articles; 130 included one article.

UoA2 (primary care) includes the greatest proportion of articles published in both the BMJ (impact factor 19.967) and Social Science and Medicine (impact factor 2.814), while UoA3 (AHPs) includes the largest proportion of articles published in Qualitative Health Research (impact factor 1.403) and the Journal of Advanced Nursing (impact factor 1.917) as well as being the sole UoA to receive submitted articles published in the International Journal of Nursing Studies (impact factor 3.561).

Looking at the UoA that represents our own research setting (primary care, UoA2), other prominent publication outlets were the British Journal of General Practice (impact factor 2.741), PLoS ONE (impact factor 3.54) and Health Technology Assessment (impact factor 4.056).

Consideration of articles submitted to REF 2014 according to their methodological approach (Table 3) reveals that the majority (412; 76%) were articles using only qualitative methods, 70 (13%) were reviews or syntheses that explicitly included qualitative research articles, 34 (6%) included both qualitative and quantitative methods, while 27 (5%) focussed on qualitative methodology rather than findings. The greatest proportion of articles submitted to REF 2014 that adopted only qualitative methods (22; 5.34%) or focussed on qualitative methodology (6; 22%) were published in Qualitative Health Research, while the greatest proportion of mixed methods articles were published in the BMJ (3; 9%) and the greatest proportion of reviews/syntheses were published in the International Journal of Nursing Studies (4; 6%) (Table 3).

Table 3 Journals with six or more qualitative health research articles entered in Research Excellence Framework 2014 categorised by methodological approach

Figures in brackets show the percentages within each journal of each methodological category.

Table shows journals with six or more articles submitted to REF. In total, 184 journals included five or fewer articles that were submitted to REF 2014: six journals included five articles; six included four articles; 14 included three articles; 28 included two articles; 130 included one article.

In line with the overall figures for qualitative health submissions (Table 3), the majority of publications submitted in the primary care UoA were reporting research conducted using solely qualitative methods (Table 4). However, 34% of the submissions in this UoA adopted other approaches, notably reviews/syntheses and mixed methods research.

Table 4 Publications submitted to Research Excellence Framework 2014 categorised according to Units of Assessment (UoAs) and methodological approach

AHP=allied health care professionals.

Figures in brackets show the percentages in each UoA of each methodological category.

Discussion and implications

The overall conclusion from our brief exploration of where high-quality qualitative health research is published is that general medical or health journals with high impact factors are the dominant routes of publication, but that there is variation according to the methodological approach adopted by articles. The number of qualitative health articles submitted to REF 2014 overall is small, and even more so for articles based on mixed methods research, qualitative methodology or reviews/syntheses that included qualitative articles. There is also great disparity between the proportions of qualitative health publications submitted to REF 2014 in each of the four UoAs, despite each covering a broad range of topics and issues amenable to research using qualitative methods.

Within the primary care UoA that represents our own research setting, and comprises 22% of the qualitative health research submitted to REF 2014, over 30% of submissions were published in one of the three journals (BMJ, Social Science & Medicine, British Journal of General Practice). Encouragingly, over a third of the qualitative health submissions to the primary care UoA were publications of reviews/syntheses, mixed methods research or articles about qualitative methodology. However, there was a general paucity of research using mixed methods or focussing on qualitative methodology or reviews/syntheses of qualitative papers across the four UoAs. We would argue that these areas are as important as ‘standard’ research using qualitative methods. First, there are many examples of the benefits of mixed methods research in gaining a fuller understanding of a phenomenon (see, eg, Yardley and Bishop, Reference Yardley and Bishop2015), and in helping ‘to characterise complex healthcare systems, identify the mechanisms of complex problems […] and understand aspects of human interaction such as communication, behaviour and team performance’ (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, O’Brien, Meckler, Chang and Guise2016). Second, publications that focus on qualitative methodology are important in advancing the field, taking advantage of new areas and encouraging the conduct of high-quality research. Third, it has been suggested that metasyntheses of qualitative evidence might give qualitative research a stronger role in decisionmaking (Gagliardi and Dobrow, Reference Gagliardi and Dobrow2011), uncover new understandings and be useful for practitioners (Seers, Reference Seers2015).

There are, of course limitations to our findings and interpretations. We have taken submission to REF as a proxy for quality, whereas publications may be submitted (or not) to REF for reasons other than quality alone. It is also not possible to know how individual publications were rated in REF 2014, only how an overall submission was judged.

If REF 2014 is indeed a true reflection of the high-quality qualitative health research being conducted by UK universities, then this indicates either that other types of qualitative research (methodological, mixed methods research and reviews/syntheses) are not frequently taking place or that this research is not considered to be of sufficient quality to be submitted to REF. A similar line of reasoning can, of course, be taken regarding the specific journals that feature in REF submissions.

The data in this short report provide an insight into the publication patterns for high-quality qualitative health research submitted to REF 2014. However, it also raises more questions than it is able to answer for those involved in health research:

-

(1) If the value of qualitative (and mixed methods) research is increasingly recognised, why was there a low number of qualitative health articles submitted to REF 2014 overall, and, in particular, why was there a lower representation of articles reporting mixed methods, qualitative methodological research or reviews/syntheses?

-

(2) Does the balance in REF 2014 between qualitative health research published in high impact general medical journals and that published in more specialist journals reflect the broader picture of where high-quality qualitative health research is published per se or is there high-quality research published in less prominent, specialist, journals that is consequently perceived as less suitable for submission to REF?

-

(3) Why is there such a disparity between the proportions of qualitative health research submitted to each of the four health-related UoAs?

Of course, patterns of publication change over time with changes to journal policies (eg, the BMJ) and the emergence of new journals (eg, the launches of PLoS ONE Footnote 2 in 2006 and BMJ Open in 2011). The next REF exercise may see changes to the patterns we have identified and reflect the whole range of good quality research that seeks to understand the complex nature of illness and health care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rebecca Whittle for help with analysis of the database.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.