Introduction

The social sciences experienced a dramatic institutional expansion during the first decades after World War II. In Europe in particular, social scientists were assigned key roles in assisting the continent’s moral reconstruction and modernist development programs. Reflection on the causes of the twentieth-century crises and the provision of critical and practical knowledge of social processes were increasingly understood as crucial ingredients of any functioning society and polity. This awareness made science and universities subject to substantially more planning and policies of state bureaucracies than they had been before (Drori et al. Reference Drori, Meyer, Ramirez and Evan2003; Neave Reference Neave and Walter2010).

While this development was widespread throughout the continent, the scope, timing, and character of this expansion was by no means uniform. Europe after 1945 was still deeply divided, and the intellectual and political traditions differed sharply in various parts of the continent. By looking at the institutionalization processes of sociology—arguably the discipline with the most general aspirations and one marked by an unusual institutional growth and public visibility during the first postwar decades (Fleck et al. Reference Fleck, Matthias and Victor2019)—in 25 European countries, this article searches for historical reasons that promoted or inhibited the expansion of social science under different political conditions.

To do that, I apply the protocol of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as developed by Ragin (Reference Ragin1987, Reference Ragin2000, Reference Ragin2008) and following Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), and proceed in four steps. First, I analyze and compare the timings when academic sociology was institutionalized in 25 European countries, covering the entire continent that includes Western European democracies, Southern European autocracies, and Eastern European socialist regimes. This analysis suggests the usefulness of distinguishing between a set of countries where sociology was fully institutionalized until the mid-1960s and another set of countries where this process was inhibited for various reasons.

In a second step, I discuss several historical reasons that are liable to explain why countries fall either in the first or the second group. Concretely, I discuss the role of prior sociological traditions and their (dis-)continuity after 1945, political regime types, the influence of larger neighboring countries, and the role of Catholicism by using exemplary case studies of both well-known and lesser known national histories of sociology.

Third, I perform formal set-theoretic analyses asking which of the historical conditions discussed before—alone or in combination—can be interpreted as necessary or sufficient conditions for successful or inhibited institutionalization of sociology. Inevitably, this section is the most technical and methodically detailed.

Fourth, I offer interpretations of these results aiming at a medium level of theoretical abstraction and pointing to new research questions for future historical case studies.

The study rests on a diverse literature dealing with the political and institutional histories of sociology as well as cognate disciplines that will be cited in the respective sections in the text. Its central contribution, however, stems from the attempt to take the comparative approach as far as possible, covering the entire European continent and their different intellectual traditions and political systems. It thus contrasts with many of the existing comparative histories of the social sciences that are often restricted to Western democracies, cover only a few cases, or leave much of the comparative reasoning implicit by presenting single case studies side by side.Footnote 1 Most directly, the study is inspired by an article by Voříšek (Reference Voříšek2008), who compared patterns of institutionalization of sociology in “Soviet Europe” in relation to the rest of Europe. His design, rooted in a comparative historical approach, results in a typology of six types of historical trajectories sociology has taken in different countries (see also Voříšek Reference Voříšek2011, Reference Voříšek2012). The present study takes up Voříšek’s basic ideas but more fully exploits the comparative approach by explicitly discussing and comparing a set of historical conditions as explanations for successful or inhibited sociological institutions across all countries using QCA. The formal set-theoretic analyses of QCA thus allow for the formulation of far more explicit theoretical implications and point to potentially more surprising similarities between apparently different institutional trajectories of sociology.

Comparing Institutional Histories of Sociology in Postwar Europe

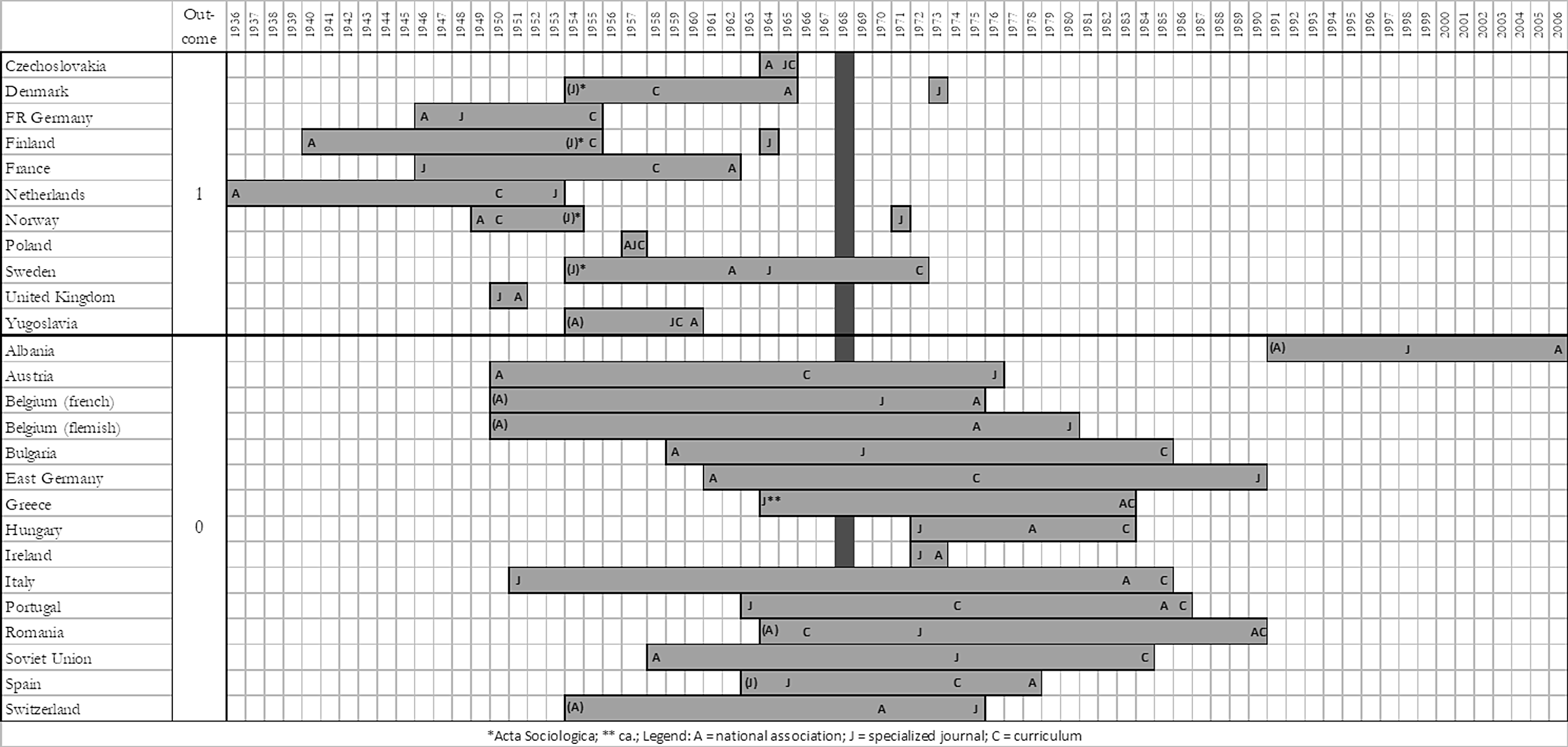

To map different institutionalization processes of sociology in Europe, table 1 shows the dates when a set of key institutions were founded in each country after 1945. Following Voříšek (Reference Voříšek2008, Reference Voříšek2012) and Heilbron (Reference Heilbron, Charles and Hans2004), and going back to ideas first formulated by Shils (Reference Shils1970), these are national sociological associations (A), specialized sociological journals (J), and the establishment of university curricula (C) that allow students to obtain a degree in sociology, roughly equivalent to a master’s degree. The existence of these institutions can be understood as a minimum requirement for sociology to flourish as an independent academic discipline because they secure the discipline’s core functions of research, teaching, and professional organization (Heilbron Reference Heilbron, Charles and Hans2004: 30).Footnote 2 Figure 1 thus displays the years when sociological associations, journals, and curricula have been introduced in each country and, by virtue of which, the duration that this process took.

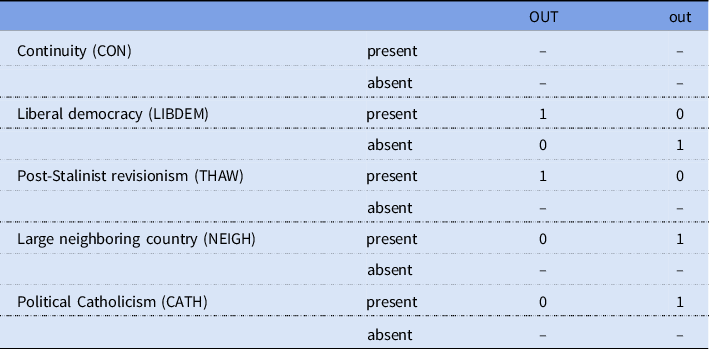

Table 1. Directional expectations

Figure 1. Institutionalization patterns of sociology in Europe.

By plotting the institutional achievements of academic sociology in postwar Europe (figure 1), several observations can be made. First, it becomes apparent that most European countries established national sociological associations before 1960 and that this was often the first step toward institutionalizing sociology. Some of these establishments were continuations of older associations that were dismantled before or during World War II. Others were first established during the 1950s, often upon initiative by UNESCO through its Department of Social Sciences (Wisselgren Reference Wisselgren2017). Only a few continuously functioned before and during World War II.

Taking additional institutional achievements into consideration, more differences among countries become apparent. Voříšek observes that not only are the dates of institutional achievements telling indicators for the conditions of the discipline but also the duration of the processes until full institutionalization has been achieved. While he draws out a typology with six different types, each associated with different historical causes,Footnote 3 it seems more fruitful to distinguish between only two groups of countries depending on the timing and duration of the institutionalization of sociology. The upper box (Outcome 1) contains countries in which sociology achieved all constituent institutional achievements within a relatively short time until the mid-1960s;Footnote 4 the lower box (Outcome 0) contains countries in which this process was inhibited in important ways.

Looking at the countries in each box reveals several unsurprising and a few surprising candidates. The earliest countries successfully institutionalizing Europe are largely no surprise: Germany, France, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, all of which have a solid institutional buildup by the mid-1950s, as do most of the Scandinavian countries even if on a smaller scale. But we also find Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia—three socialist countries that each have rather different stories. Among the countries in the lower box where the institutionalization of sociology was inhibited, we likewise have unsurprising candidates such as strict autocracies (e.g., Albania, East Germany, and Portugal) as well as a set of Western democracies such as Belgium, Ireland, Austria, and Italy, some of which are surprising because they had already developed serious sociological intellectual traditions before the war or continued to produce prolific intellectual discourses during the postwar period.

The data further suggest that a line can be drawn around the year 1968 when institutionalization in the successful countries is in principle completed. Quite generally, the 1950s can perhaps be called the decade when hopes and optimism in the healing powers of the social sciences were the highest, resulting in serious institutional efforts on national and international scales. The growth of universities was impressive throughout the 1960s in most countries of Europe and they became key arenas for political debate, culminating in the various 1968 student movements. While institutional expansion continued after the 1960s, universities throughout Europe were later increasingly preoccupied with managing the drastically enlarged academic system.

East of the Iron Curtain, 1968 marked the end of the liberalization of the “thaw” period initiated by Khrushchev in 1956. Intellectuals benefitted in particular by gaining more freedom to express critical views of socialist realities (Kolář Reference Kolář2016; Kozlov and Gilburd Reference Kozlov, Eleonory, Denis and Eleonory2013; Radchenko Reference Radchenko2014: 141). Not too dissimilar to the postwar phase in Western Europe, the decade from 1956 to 1968 was also a phase of great expectations and political experiments accompanied by economic growth and scientific investment in the East. The Soviet (and Allied) armed forces’ invasion into Czechoslovakia in 1968 changed in many ways the spirit of optimism of the decade before and led to more mediated forms of reform.

The data thus support the historical impression that the level of hope invested into the social sciences climaxed somewhere between the 1950s and the early 1960s, and that sociology received its strongest support during these years unless political resistance was strong.

Looking at cases of inhibited institutionalization also reveals that all institutional achievements are required to speak about an institutionalized sociology. Bulgaria represents an example of authoritarian restrictions to sociology, yet the country saw the establishment of a sociological association as early as 1959 and attracted international attention by staging the Congress of the International Sociological Association (ISA) in Varna in 1970. Nevertheless, it took until 1985 before a sociological curriculum was founded that led to a degree in sociology and it is hardly meaningful to speak of a fully institutionalized sociology in Bulgaria before the 1980s. Indeed, national associations are seemingly the most universal institutional indicator, arguably because membership in the ISA was considered a matter of prestige and thus associations were sometimes quickly established, even in the absence of otherwise active sociological communities.

While I argue that these institutional differences reveal many interesting differences between the sociologies produced in each country, the relation between institutional and intellectual success is of course not straightforward. Possibly with the exception of Albania (Tarifa Reference Tarifa1996), some kind of sociological research was produced in every European country during the years under consideration. Among those countries here counted as institutionally unsuccessful sociologies, some had vibrant intellectual scenes that included interesting sociological work, such as Italy or Hungary. Yet the barriers to institutionalizing sociology also hindered its intellectual progress. Other countries with favorable institutional conditions might have relatively marginal intellectual impact in retrospect. But again, their institutional success enabled the establishment of new intellectual trends. The exact relation between institutional histories and intellectual traditions might not be resolved here, but this article will provide insights into how they are linked, and which differences and parallels are suggested by their comparative analysis.

The institutional view also reveals that national differences indeed matter because it was primarily state institutions that drove the project of academic expansion after 1945. The internationalization of the social sciences, which makes the transnational view increasingly important, became most relevant in the 1970s and 1980s (Heilbron et al. Reference Heilbron, Nicolas and Laurent2008). Therefore, postwar Europe is an arena where state interventionism was, by all historical standards, unusually strong and fundamentally shaped the conditions for sociology.

Historical Conditions

With the assumption that the differences between countries with successful and inhibited institutionalization of sociology are related to political processes within these countries, I will now discuss several conditions that appear as possible explanations for these differences. Following the protocol of QCA, these conditions are retrieved from single case studies, but formulated in such a way that their presence or absence can be treated as historical conditions influencing each country’s propensity to belong to the set of successful or inhibited institutionalization of sociology during the postwar years. For the formal analyses in the following sections, it is important to explore whether the presence or absence of each condition can be associated with a clear expectation that it leads to successful or inhibited institutionalization of sociology. As will be shown, these expectations are sometimes inconclusive or asymmetrical.Footnote 5

Continuity

The first condition is the existence of well-established sociological institutions before World War II. The relevance of this condition becomes evident when one looks at the group of countries that Voříšek calls the “Established type.” In Germany, for example, a sociological association was founded in 1909 and remained active into the early phase of National Socialism. After the end of World War II, the association was able to revive quickly, resuming its activities in 1949. Similarly, journals that were already published during the interwar years, such as the Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, were relaunched quickly, enabling German sociology to reach full institutionalization within a few years.

If one considers the Scandinavian countries, where full institutionalization was reached without such strong prior traditions, tradition cannot be treated as a necessary condition. Examining the countries that became part of the Socialist bloc after World War II, the role of sociological traditions becomes even more complicated. In Poland and Romania (and to a lesser degree Czechoslovakia), sociology was well established during the interwar years and continued in the immediate postwar years. However, with the establishment of the Stalinist regimes in 1948, sociological institutions were almost entirely shut down. Among these countries, only in Poland did large parts of the older intellectual elite retain their positions in academia (Duller and Fleck Reference Duller, Christian and Kathleen2017). During the post-Stalinist thaw, initiated by the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956, many prewar Polish sociologists were still active, playing important roles in the quick reinstitutionalization of the discipline (cf. Bucholc Reference Bucholc2016). However, this was a major exception in the bloc. In East Germany (GDR), old academic cadres were thoroughly purged from the universities with the installation of the Communist dictatorship. As a result, older sociological tradition, even if present, could not be revived (cf. Connelly Reference Connelly2000; Jessen Reference Jessen1999; Sparschuh and Koch Reference Sparschuh and Ute1997). In Romania, the interwar tradition did not disappear, but neither did it provide legitimization for the sociological discipline. In a short phase of political relaxation after Nicolae Ceaușescu resumed power in 1965, sociological institutions were established under the guidance of the Minister of Education and former sociologist Miron Constantinescu, but soon came under close control and repression again (Bosomitu Reference Bosomitu2011, Reference Bosomitu2017; Tismaneanu Reference Tismaneanu2003: 260). The case of the Soviet Union is of further interest. Although no strong sociological institutions had existed prior to World War II, the later history of the discipline shows that those sociologically interesting elements of the Marxist tradition were viewed with even more skepticism than so-called bourgeois Western sociology. Older Marxist writings, it transpired, had much more potential to disturb the monopoly of the party over ideological discourse than the Western sociological tradition that was, in part at least, considered neutral enough to be granted some space in the academic sphere.

To summarize, an older sociological tradition only appears to explain why some countries developed sociological institutions immediately after the end of World War II. Within the larger time frame until the late 1960s, it offers no clear implications for the differences between countries with either rapid or inhibited institutionalization. In fact, under conditions of regime change or close ideological control, tradition might have had a detrimental effect on the institutionalization of sociology because it held potential affinities with old elites.

These discussions remind us that the term “tradition” insufficiently captures the relevant phenomenon. The crucial question is whether or not older sociological traditions were able to effectively continue their activities at universities and other academic institutions after World War II. The first condition is therefore called Continuity (CON), consisting both of the existence of an older sociological tradition and the effective chance of its continuation during the postwar years. Therefore, Austria and the GDR are, for different reasons, not members of this set, even if they had strong prewar sociological traditions. In Austria, Nazism and World War II resulted in an almost complete exodus of its intellectual elite (Fleck Reference Fleck2011). In the GDR, prewar scholars from the social sciences and humanities were almost all dismissed, and later generations were meticulously chosen and politically indoctrinated (Connelly Reference Connelly1997; Duller et al. Reference Duller, Christian and Schögler2019; Jessen Reference Jessen1999).

Given the different and contradictory implications of the condition of “continuity” for the institutional developments of postwar sociology, depending on other historical circumstances, no directional expectations can be formulated for the presence or absence of that condition (see table 1).

Liberal Democracy

The second condition refers to the type of political regime under which sociology had to work. There is a well-established belief (Connelly and Grüttner Reference Connelly and Michael2003; Drori et al. Reference Drori, Meyer, Ramirez and Evan2003; Kirtchik and Heredia Reference Kirtchik and Mariana2015; Parsons and Platt Reference Parsons and Platt1973) that the social sciences in general, and sociology in particular, can only blossom under the conditions of liberal democracy, while authoritarian regimes tend to suppress such intellectual activities.

The connection is rather obvious when considering right-wing dictatorships. Nazi Germany had a devastating effect on the social sciences, forcing almost an entire generation to leave their home country and begin new a life elsewhere (Fleck Reference Fleck2011). However, Germany is not alone; right-wing dictatorships also affected Italy, Portugal, and Spain, among others, with rather different outcomes.

Portugal, which was under a fascist military dictatorship for almost half a century from the 1920s until 1974, is another case of a direct negative connection between dictatorship and sociology. Individual scholars might have been able to pursue research and writings that can be qualified as “sociological,” but the label “sociology” was largely banned from use. Portuguese dictator Salazar conceived of sociology as “socialism under disguise” and the term smacked of leftist progressivism to him (da Silva Reference da Silva2015: 16; Nunes Reference Nunes1988: 37). When the fascist regime eventually fell in 1974, sociology experienced an explosive upswing and quickly developed research and teaching institutions of various orientations (da Silva Reference da Silva2015).

Yet in Italy, sociology found comparably favorable conditions under Mussolini’s fascist reign. Indeed, many of Italy’s sociological pioneers, such as Vilfredo Pareto, Robert Michels, and Corrado Gini, either had sympathies or became allied with the fascists. After 1945, the alliance between sociology and fascism was one of the major hindrances for sociology to take root in the academic system—a process related to a complex case of the continuity of prewar traditions (cf. Grüning et al. Reference Grüning, Marco and Andrea2019). In effect, the relation between fascism, democracy, and the chances for sociology to thrive is ambiguous, if not the reverse of conventional wisdom.

In Spain, to cite a final example, the fascist/authoritarian rule under Franco persisted into the second half of the 1970s. With political pressure and control decreasing during the postwar period, Spanish sociologists found some space to institutionalize. The explanation for why sociology could attract reasonable degrees of government support even under politically adverse conditions is that social change necessitated institutions that reflected on and managed these processes of change. In short, regimes of all kinds that were going through phases of rapid social change needed social scientific knowledge and thus built or supported institutions that produced knowledge relevant to the change.

This is also true for the other grand type of authoritarianism in Europe, “real socialism,” where the Communist parties usually endorsed strongly interventionist, social engineering–like programs that had a built-in penchant for the social sciences. Stalinism, however, initially had a catastrophic effect on sociology (Keen and Mucha Reference Keen and Mucha1994, Reference Keen and Mucha2003, Reference Keen and Mucha2004). While for fascists and conservatives, sociology often sounded synonymous with socialism, the Stalinists associated it with “bourgeois reaction.” Whatever social knowledge could legitimately be produced had to be defined as a subordinate element of the doctrine of Marxism–Leninism. But Stalinism ended in 1956 and with it doctrinarian rigor gave way to a phase of revisionism. Thus, large parts of the socialist period need to be placed in the historical context of post-Stalinist “thaw” (cf. Kolář Reference Kolář2016). While there are important differences in degree and timing, leeway for social scientists, and sociologists in particular, became much larger during the later 1950s and 1960s in most socialist countries (Voříšek Reference Voříšek2008: 93). The production of social knowledge evidently requires a sufficient degree of academic freedom. The fundamental dilemma for authoritarian regimes of being in need of social knowledge while also needing to undermine the flourishing of centers of independent thought that might threaten the regime’s legitimacy (Connelly Reference Connelly2003: 10) complicates the connection between democracy and the chances for sociology’s institutionalization.

Nevertheless, social knowledge can mean different things and not all of them require autonomous sociological institutions organized as universities. In 1970, for example, a top-secret “Information-Sociological Center” was established in Bulgaria with the task of providing knowledge to the Communist Party’s Central Committee about how the population felt and thought about various policies (Dimitrov Reference Dimitrov2014). Certainly, no curriculum, never mind an academic journal, could fulfill this function.

It can be argued that the full set of institutions defined as our outcome enables a discipline to unfold its intellectual activities in a relatively autonomous way, and that a regime that allows these institutions to be established does not generally distrust their proponents. I will therefore define the second condition as the set of countries with liberal democratic regimes throughout the period of observation (1945–68), which is characteristic of most West European countries. Nonmembers of this set are all countries with socialist regimes, as well as Spain, Portugal, and Greece.

The directional expectation for the condition of liberal democracy is straightforward: the presence of democracy is expected to contribute to the institutional development of sociology, while its absence decreases the chances of an institutionalized sociological discipline.

Post-Stalinist Revisionism

From the perspective of the socialist countries, it is apparent that those countries with a rapid and early institutionalization of sociology are among the more liberal of the regimes. Voříšek emphasizes that in these countries sociology was institutionalized in revisionist phases, that is, phases of relative political liberalization and internal political and ideological reform as well as attempts at an emancipation from Soviet domination. This connection is clear in the case of Yugoslavia, which very actively sought its own path toward socialism after it famously departed from the Soviet Union in the wake of the Cominform conflict of 1948. Under the most liberal conditions of all socialist countries in Europe, sociology was very quickly developed between approximately 1954 and 1960 with rather negligible prior traditions (Batina Reference Batina2008; Duller Reference Duller, Adela and Victor2018; Lazić Reference Lazić2011). Czechoslovakia is another case in point. During its phase of reform and liberalization that eventually led to the Prague spring in 1968, extensive sociological research began and a whole institutional setup was established (cf. Skovajsa and Balon Reference Skovajsa and Jan2017; Voříšek Reference Voříšek2012). This connection is underlined by the fact that the disciplines had been cut back and severely censored after the invasion of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia in August 1968, which meant the end of the reform process.Footnote 6 While Poland also unambiguously falls into the group of revisionist countries with relative high degrees of liberties after 1956, Hungary is an interesting case to consider. While Hungary’s relative liberality could be considered a case of “thaw,” its implications for sociology were of a different kind. A brief, and eventually unsuccessful, phase of relaxation was initially triggered by Moscow only a few months after Stalin’s death in 1953. The Moscow-favored reformer Imre Nagy, however, soon lost support in the Soviet administration and had to succumb to his Stalinist rivals in Hungary by 1955 (Radchenko Reference Radchenko2014: 146). The following uprising of dissatisfied masses and many Budapest intellectuals culminated in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. This was no longer revisionist, but explicitly anti-Soviet and anti-Communist and was crushed brutally by Warsaw pact forces in the autumn of 1956. From the perspective of the possibilities for sociology to develop long-standing institutions, it could be argued that Hungary’s “thaw,” ironically, came too early. At the time when Yugoslavia or Poland invested most heavily in the expansion of sociological institutions during the second half of the 1950s, Hungary, under the impression of the Soviet crackdown, took a more moderated and controlled approach to post-Stalinist liberalization. Clearly, Hungary saw a multifaceted intellectual life, and sociology was an important element in it, but the establishment of sociological research centers and possibilities to study remained severely restricted (cf. Karády and Nagy Reference Karády and Péter Tibor2019; Takács Reference Takács2016).

Therefore, we define the third condition as a distinct phase of post-Stalinist thaw (THAW). More than for other conditions, this one illustrates the centrality of the timing of events. One historical phenomenon—a movement of internal political liberalization and external emancipation from a hegemonic power—can have conducive or inhibiting effects on the institutionalization of sociology, though only a year apart.

Because this condition only makes sense for the socialist countries, its negative pole (= the nonmembers of this set) consists of a very heterogeneous group of nonsocialist countries (democratic or not) and socialist countries with a more stable authoritarian regime during the period of interest. Therefore, the directional expectations for THAW are also asymmetric: a clear implication for institutionalized sociology can only be expected for the presence of the condition, but not for its absence (see table 1). Because only three countries exhibit the presence of THAW, the data for this set are highly skewed.

Large Neighboring Country

A fourth condition is needed to discriminate between the democratic countries with successful and inhibited sociologies. It appears that many of the Western democratic countries that experienced slow and inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology are small countries. Voříšek mentions that conservative academia and the lack of demand for sociologists in the labor market are the decisive factors inhibiting the growth of sociology in these cases (Voříšek Reference Voříšek2012: 23). However, academics’ aversion to competing fields of knowledge seems a rather universal phenomenon. His other remark that the lack of a professional labor market prevents sociology from institutionalizing is even less convincing because one would expect labor markets to develop after the respective professionals exist and not vice versa. Another structural similarity of the small countries with slow institutionalization, however, is that these countries find themselves in a marginal position next to an existent sociological community in a large neighboring country (Voříšek Reference Voříšek2008: 99).

While small countries in general have a natural tendency toward bandwagoning, this tendency is even larger when they neighbor a culturally or linguistically similar country. The possibility of benefitting from solutions developed and tested elsewhere, without taking the risks of experimenting for oneself, is a welcome opportunity and favors conservatism. In the case of institutionalizing sociology, this means that small countries with a larger neighboring country speaking the same language (NEIGH) might have less incentive to develop their own sociological institutions because their need for the relevant social knowledge is smaller. From the perspective of aspiring sociologists, another possible mechanism is that getting access to the neighboring sociological institutions, either through receiving university training or through accessing the sociological labor market, is a great deal easier than establishing sociological institutional structures against the academic conservativism at home. Members of this structural condition are Austria, Ireland, Belgium, and Switzerland. Belgium and Switzerland are concerned in multiple ways because they contain more than one linguistic group, each neighboring a large sociological community. In Belgium, one should indeed speak of two distinct sociological communities for the Flemish and the Walloon parts of the country, each entertaining distinct institutional structures and having relatively limited contact with each other (Vanderstraeten Reference Vanderstraeten2010: 573). The Belgian Society for Sociology, initially founded in 1899, was reestablished in 1950, but eventually split into two different organizations in 1975, one for French and one for Flemish. Similarly, each linguistic community had their own academic journal (Recherches Sociologiques since 1970, and Tijdschrift voor Sociologie since 1980).

Of special interest in this respect is Scandinavia, where regional cooperation has been a particularly strong feature of the postwar sociological development and linguistic comprehensibility between the dominant languages (with the exception of Finnish) is high. However, they are not treated as members of the condition NEIGH because they lack the asymmetry—both in size and temporally—that is characteristic for this kind of relation to yield its effect. For instance, launching the international English-language journal Acta Sociologica—Journal of the Nordic Sociological Association in 1955 arguably limited the need for further (national) sociological journals. However, in the egalitarian scenario of culturally similar nations of similar size, the neighboring effect on the institutionalization of sociology is rather supportive than inhibiting.

Finally, East Germany might be treated as fulfilling the condition because it neighbors the larger and sociologically prolific Federal Republic of Germany. This remained, however, without effective consequences because of the impossibility of entertaining any kind of cross-border activities with West Germany. While an open border with West Germany existed in practice until 1961, its effect was mainly to get rid of critical intellectuals with virtually no possibility for feedback into the GDR, whose academia was strictly surveilled by the one-party state.

While the presence of a large neighboring country is expected to reduce the chances of developing institutionalized sociology, the absence of such a neighbor per se does not seem to stimulate the expansion of sociology in a given country. Therefore, the directional expectations are again asymmetric with a negative expectation related to the presence of NEIGH and no clear expectations attached to its absence (see table 1).

Political Catholicism

While Ireland has with the United Kingdom a larger neighbor speaking the same language, the literature on Irish sociology casts doubt as to whether this structural factor is the best of explanations for its inhibited sociological institutions in the postwar years. Here, anticolonial sentiment fueled Irish nationalism, which was to a large extent built on Catholicism, resulting in a “considerable insularity” of Irish intellectual life during most of the twentieth century (Fanning and Hess Reference Fanning and Andreas2015: 8). The strong role of the Catholic Church has, however, led to an institutionally well-established Catholic sociology in Ireland. Pursued and promoted largely by Catholic priests, and following two papal encyclicals on social issues from 1891 and 1931 as their foundational documents (Conway Reference Conway2011: 35), this strand of social science selectively adopted methods from international sociology but rejected most of the discipline’s intellectual content that it derided as “secular sociology.” Thus, although from a nominalist standpoint Catholicism had direct positive effects for the institutionalization of “sociology” in this case, this variant is considered (in accordance with its proponents’ self-understanding) as a competitor to sociology in its broader international meaning, rather than as a version of it.

In fact, within the sociologically unsuccessful European democracies, some forms of Catholicism have dominated most of their intellectual spheres. Austria is a good case in which all educational policies have been in the hands of the conservative People’s Party during most of the postwar period, which championed Catholic social teaching over rival systems of social thought (cf. Fleck Reference Fleck2016). Belgium, whose University of Leuven has been the world’s leading center of Catholic sociology, further exemplifies the point. Because of the competition between Catholic social thought and the secular version of sociology that has increasingly become the only internationally legitimate version of sociology, strong traditions of political Catholicism count as a major inhibitor to the institutionalization of sociology. We thus define a fifth condition, political Catholicism (CATH), whose members are those countries in which the Catholic Church has exerted significant influence on the political conditions in general and the universities and social thought in particular. In addition to the countries already mentioned, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are members of this set. Poland is not considered a member of this set because Catholic influence was severely limited after the Communist takeover and its impact on educational policies were comparatively marginal.

As with the larger neighbor, the condition of political Catholicism has been identified as an explanatory factor for several cases of inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology, but the absence of Catholicism per se cannot be expected to help sociology gain institutional support, because there are other similarly conservative alternatives such as Greek Orthodoxy. The directional expectations for CATH are thus asymmetrical with a negative expectation related to the presence of CATH and no clear expectations attached to its absence.

Table 1 summarizes the five conditions and their symmetrical or asymmetrical directional expectations for the outcome.

Formal Analyses

It is now possible to decide for each country whether or not it is a member of the set for each condition and the outcome regarding the institutionalization of sociology. In all cases, “1” denotes that the country is a member of the set, and “0” denotes that it is a nonmember. The outcome column, to repeat, indicates whether a country has experienced full institutionalization of sociology until the mid-1960s (“1”), or inhibited institutionalization (“0”). This information is given in the data matrix (table 2). In the next steps, we can determine which of the conditions fulfill the logical requirements to be called necessary and/or sufficient conditions for either one of the two poles of the outcome.

Table 2. Data matrix

Necessary Conditions

On the basis of the data matrix, we can determine the necessary conditions by asking which conditions are always present when the outcome is present.

Table 3 Footnote 7 displays all single conditions, disjunctions, and conjunctions (with a minimum consistency score of 0.9) for the positive outcome.Footnote 8 Following Schneider (Reference Schneider2018), empirical superset relations are only to be interpreted as necessary conditions if they are (a) empirically consistent, (b) empirically relevant, and (c) conceptually meaningful, the latter of which applies in particular to conjunctions (logical AND, noted as*) and disjunctions (logical OR, noted as +). Among the seven terms that surpass the consistency value of 0.9, I interpret only one as a necessary condition for the outcome (LIBDEM+THAW). In other words, the data suggest that it is necessary to have either liberal democracy or a distinct phase of post-Stalinist thaw for sociology to achieve full institutionalization during the postwar period. The implications of this finding will be discussed in the interpretations in the text that follows. At this point, it should be noted that disjunctions (or unions) of conditions are only interpretable for statements of necessity if they can be thought of as functional equivalents and point to a common concept of higher order (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 74). LIBDEM and THAW fulfill this criterion as they both indicate a minimum degree of political liberty under which sociological institutions can thrive.

Table 3. Superset analysis, OUT = 1

* RoN = Relevance of Necessity.

Two single conditions—the absence of a large neighboring country and the absence of political Catholicism—as well as their conjunction are also consistent with the necessity assumption. Their relevance score, however, is too low, which is why I refrain from interpreting them as a necessary condition. The three other disjunctions that pass the consistency level of 0.9 are highly irrelevant and conceptually meaningless.

Table 4 shows the results of applying the same procedure to explaining the negated outcome, that is inhibited institutional sociology.Footnote 9 Following the same reasoning as the preceding text, none of the empirical superset relations can be interpreted as necessary conditions for inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology. The only two disjunctions with satisfactory relevance scores (libdem+NEIGH, libdem+CATH) do not point to any meaningful higher order concepts. Thus, the data do not suggest the existence of any necessary conditions to explain inhibited institutional sociology.

TABLE 4. Superset analysis, OUT = 0

* Relevance of Necessity

Sufficient Conditions

Sufficient conditions are such that in their presence, the outcome is always present. To determine which conditions (or combinations thereof) fulfill this logical requirement, it is necessary to first compile the so-called truth table (table 5). Each row in the truth table represents one possible combination, or configuration, of conditions. The outcome column indicates which configurations of conditions are deemed sufficient to explain the outcome (1) and which are not (0). Within these data, all configurations with an outcome value of “1” are empirically connected with cases of successful institutionalization of sociology, and all configurations with an outcome value of “0” are connected with cases of inhibited institutionalization.Footnote 10 Configurations that do not exist empirically (rows 12–32) are called logical remainders or counterfactuals. Their outcome value is unknown and thus denoted with a question mark.

Table 5. Truth table

Table 5 displays the 11 empirically observed configurations of conditions in these data and the remainders. Rows 1–4 show configurations leading to the positive outcome (full institutionalization), and rows 5–11 show different configurations that lead to the negated outcome (inhibited institutionalization). As an initial result, these configurations of present or absent conditions can be interpreted as different “causal pathways” to explaining why some countries saw successful institutionalization processes of sociology and others saw inhibited processes, thus constituting an empirically grounded typology.

To make these results more accessible to interpretation, they can be further minimized to arrive at more parsimonious solution terms from which stronger theoretical conclusions can be drawn.

According to the current standards in QCA, I produced four different solution terms for each pole of the outcome: the complex solution, the enhanced intermediate solution, the enhanced parsimonious solution, and the most parsimonious solution. Technically, they differ in the more or less permissive use of the logical remainders to make the solution terms shorter. Practically, the theoretical interpretations of these solution terms depend on a number of factors, both technical and contextual.

The complex (sometimes called conservativeFootnote 11 ) solution is the most basic minimization procedure and simply removes redundant elements by applying the Quine–McCluskey algorithmFootnote 12 without using any of the nonobserved logical remainders. On the other end of the spectrum is the most parsimonious solution that uses all logical remainders inasmuch as they contribute to make the solution term shorter. As a rule, the more configurations are included in the minimization procedure, the greater the possibility to make the solution shorter. Including all remainders, the most parsimonious solution is thus the shortest possible expression that does not contradict the empirical data. These two solutions, the complex and the most parsimonious, define the outer limits of the analytical space within which the interpretation of the results take place. Between them, two more solution terms are useful, following the (theory-guided) Enhanced Standard Analysis protocol, as suggested by Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2013). The third solution is called the enhanced parsimonious solution, which removes those logical remainders from the minimization that contain untenable assumptions. In these data, untenable assumptions are, on the one hand, those truth table rows containing both liberal democracies and countries with distinct phases of post-Stalinist thaw periods (LIBDEM*THAW, truth table rows 18–21 and 29–32). By definition, countries cannot be liberal democracies and have experienced a strong phase of post-Stalinist revisionism, which makes these configurations meaningless. Truth table rows containing this expression should thus not be used for the minimization. On the other hand, remainders containing libdem*thaw are excluded for the explanation of the positive outcome because this term represents the negation of the term LIBDEM+THAW, which we had identified as a necessary condition for the positive outcome. As Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2013) have shown, it contradicts logic that the negation of a necessary condition is at the same time a sufficient condition for the same outcome. Therefore, truth table rows 12, 13, and 22–24 are untenable and thus excluded from the minimization of the positive outcome.Footnote 13

The fourth solution is the (theory-guided) enhanced intermediate solution. In addition to removing untenable assumptions, the enhanced intermediate solution uses the directional expectations that have been formulated in the theoretical sections on the selection of conditions. Here, remainders are only used for the minimization if they make the solution shorter and are in accordance with these expectations (Ragin and Sonnett Reference Ragin and Sonnett2005). While the enhanced standard analysis uses directional expectations for single conditions, the theory-guided enhanced standard analysis (TESA) also formulates conjunctural directional expectations for entire truth table rows, where theoretical expectations are attached to conjunctions of conditions. In the present case, I formulate positive conjunctural expectations for the positive outcome of two truth table rows (26 and 28). These counterfactuals represent countries with a continuity of a prewar tradition, either a democratic one (28) or one with a distinct post-Stalinist revisionism (26), no political Catholicism, but a large neighboring country of the same language. The reasoning for expecting a positive outcome related to these configurations is that the NEIGH condition supposes that it is easier to use social knowledge from a neighbor and their institutional infrastructure rather than to build new sociological institutions against the academic conservatism at home. Given the assumption, however, that a strong prewar tradition had already established these institutions beforehand, this mechanism does not seem plausible to prevent sociology from reinvigorating itself. Although the single directional expectations of the conditions CON (-) and NEIGH (0) would suggest these remainders to be used for the negated outcome (inhibited sociology), in conjunction they appear more likely to produce the positive outcome (successful institutionalization). Therefore, the two remainders 26 and 28 are excluded from the minimization process for the sufficiency analysis of the negated outcome.Footnote 14

To sum it up, the (theory-guided) enhanced intermediate solution uses only those counterfactual truth table rows that make the solution terms shorter (more parsimonious), that are in accordance with the directional expectations (easy counterfactuals) and that do not contradict necessity statements or common sense (untenable assumptions).Footnote 15 In the following interpretations, I mostly refer to these solution terms, but also discuss their relation to other solutions. Tables 6 and 7 display all solutions in their order of parsimony.

Table 6. Subset analysis, OUT = 1

Table 7. Subset analysis, OUT = 0

To explain full institutionalization of sociology during the postwar years, the most parsimonious solution offers two rather short sufficient terms. It suggests that, on the one hand, having experienced a strong phase of post-Stalinist revisionism (THAW) is sufficient to achieve full institutionalization of sociology. This covers the three socialist countries Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Poland. Alternatively, it suggests that it is sufficient to have liberal democracy and, at the same time, neither a larger neighboring country of the same language nor a strong influence of the Catholic church (LIBDEM*neigh*cath). All eight democratic countries with a positive outcome are covered by this solution term.

To arrive at this rather elegant solution, a large number of untenable counterfactuals have been used in the minimization. In addition to the eight meaningless counterfactuals, as many as 12 (out of 14) are also contradictory, that is they are also used for the most parsimonious solution of the negated outcome (see the following text). Despite these technical objections in terms of interpretation, as we will see shortly, this solution covers some crucial elements of explaining institutionalization effectively, even if it excludes some important elements.

The enhanced intermediate solution, for which all untenable and difficult counterfactuals (which happens to mean all counterfactuals altogether)Footnote 16 have been removed, consists of two solution terms that are not so much different. The term LIBDEM*thaw*neigh*cath is identical to the one from the most parsimonious solution, except that “thaw” could not have been removed. The absence of a post-Stalinist revisionism, however, is logically implied in the presence of LIBDEM and therefore of no informative value. Yet the second term (libdem*THAW*neigh*cath) does point to a difference. While the absence of LIBDEM is again included in THAW, the additional conjunctive elements “absence of larger neighbor” and “absence of political Catholicism” raise the (counterfactual) question asking what would have happened to revisionist socialist countries had they also shown either of these unfavorable conditions. The consistent connection of the two conditions NEIGH and CATH with inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology throughout all formal analyses suggests that their inclination toward inhibited sociology could possibly outweigh the positive implication of THAW. After all, just like LIBDEM, THAW appears to fulfill the minimum requirement of a certain political liberty, and thus a necessary condition, but appears to carry little weight as a sufficient condition.

One condition (CON) could be entirely reduced from all solution terms, suggesting that the existence of a continuity of a prewar tradition has no implications for explaining full institutionalization of sociology during the postwar years. The disappearance of the CON-condition for the sufficiency analysis of the positive outcome is, however, subject to a certain degree of uncertainty due to model ambiguity (Baumgartner and Thiem Reference Baumgartner and Alrik2017).Footnote 17 An alternative, though slightly less robust, way of reducing the data would suggest that the existence of a prewar continuity only leads to the successful institutionalization of sociology in the simultaneous absence of strong Catholic influences. This will be more thoroughly discussed in the section explaining the negated outcome.

In light of the considerations presented so far, the best representation of the sufficiency analysis for successful institutionalization of sociology would be:

In words: The sufficient conditions that allowed for full institutionalization of sociology in the postwar years include liberal democracies with no larger neighboring countries of the same language and no strong influence of the Catholic church; or socialist countries that experienced strong phases of post-Stalinist revisionism and with no larger neighboring countries of the same language and no strong influence of the Catholic church.

Following the same logic, table 7 displays the four solution terms for the negated outcome. The most parsimonious solution once again highlights the power of the two conditions NEIGH and CATH, suggesting that each of them is sufficient to lead to inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology. The third term, libdem*thaw as a sufficient condition for OUT = 0, is logically implied in calling LIBDEM + THAW necessary for OUT = 1 and is thus consistent with earlier results in this article. Again, the simplifying assumptions used to arrive at this solution contain plenty of untenable assumptions. Therefore, I will turn to the theory-guided enhanced intermediate solution that differs in several interesting ways.

The theory-guided enhanced intermediate solution suggests three distinct configurations that are sufficient for inhibited institutionalization processes of sociologies in postwar Europe. The first refers to the simultaneous absence of democracy, post-Stalinist revisionism, and a larger neighboring country of the same language, by which no less than nine countries are covered. It seems safe to assume, as the most parsimonious solution does, that the absence of a larger neighbor can be seen as redundant in light of libdem*thaw. The interpretation of LIBDEM+THAW as necessary for the positive outcome means exactly that: any configuration containing libdem*thaw, irrespective of all other conditions, leads to the negated outcome.

The two other terms (con*thaw*NEIGH + CON*thaw*CATH), however, each contain the continuity condition, but in interestingly different ways. Because the five countries covered by these two terms are all democracies, I will disregard the absence of THAW and focus on the other two conditions instead. On one hand, interpreting CON*CATH as a sufficient condition for inhibited sociology points to the problem described earlier for Italy, Belgium, and Ireland, that the strong and continuous presence of Catholic intellectuals posed a serious brake for modern secular sociology to claim their place in universities and elsewhere. On the other hand, the condition of a larger neighboring country appears as an inhibiting factor together with the absence of prewar continuity. This, in turn, supports the argument formulated in the preceding text in relation to the conjunctural directional expectation for TT rows 26 and 28: that NEIGH is to be understood primarily as a factor discouraging institutionalization efforts because the neighboring intellectual infrastructure is easily accessible. It is not, however, a factor that actively counteracts the development of sociological institutions.

Considering the explanatory value of the different solution terms of the sufficiency analysis for the negated outcome, the most parsimonious solution is problematic. Beyond the use of untenable counterfactuals, many cases are covered by multiple solution terms. Five out of six cases covered by CATH are also covered by other terms. On the other hand, the discussion about the role of prewar conditions, absent from the most parsimonious and enhanced parsimonious solutions, captures important arguments. Therefore, the best representation of explaining inhibited institutionalization processes of sociology might be:

In words: The conditions that have prevented sociology from developing full institutionalization during the postwar years are the simultaneous absence of both democracy and a distinct phase of post-Stalinist thaw; the absence of a continuously present sociological prewar tradition together with a larger neighboring country of the same language; and the simultaneous presence of a strong prewar tradition under the strong influence of the Catholic church.Footnote 18

Interpretation

What can be drawn from these results? The first insight is the necessity assumption of the term LIBDEM+THAW. It suggests that for sociology to thrive institutionally and intellectually, a certain degree of political liberties is necessary. This degree, as the three socialist examples show, has at times been granted by authoritarian regimes when their perceived need for critical reflection on social affairs outweighed their fears of a larger number of independent thinkers that potentially challenged the regime’s understandings and public information policies. A different reading of the same result would be that the degree of political liberties necessary for sociology to be institutionalized was not very high, and that authoritarian regimes were willing to allow limited intellectual freedoms that they were ready to contain when needed.

The fact that LIBDEM*THAW is a necessary but not sufficient condition draws our attention to additional factors that inhibit sociology from expanding its influence. Here, the results ask for more complex explanations. Drawing from case knowledge from national histories, I looked at two conditions in particular: the existence of a larger neighboring country with the same language and a strong influence of Catholicism on intellectual affairs. The different implications of continuously present prewar traditions depending on other contextual conditions bring to light the analytical potential of configurational methods. While CON appears to have no implications for explaining full institutionalization, it plays important but distinct roles in the explanation of inhibited sociology: In combination with CATH, the continuous presence of prewar traditions leads to well-established conservative social science that prevents more modern versions of it to take root; in combination with a large neighboring country of the same language, the absence of CON helps diminish the need to establish institutions even if active resistance against sociology is relatively low.

At the same time, when looking at the cases associated with CATH and NEIGH, an important limitation of set-theoretic analyses becomes apparent. The problem arises from the fact that CATH and NEIGH intersect to a large degree, which is to say that many countries with a large neighboring country also exhibit strong influence of the Catholic church. Only four cases (Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland) exhibit one of the two conditions. The other 21 cases exhibit either both conditions or none of them. For the cases in which the conditions intersect, set-theoretic analysis cannot distinguish which of the conditions was at play. Here, we have to resort to case studies again. It might well be that in some cases both factors have played a role, such as in Belgium and in Austria. It might also be that the continuity of a prewar tradition is in fact related to a more complex configuration of actors that does not only consist of Catholics. The Italian case is certainly insufficiently described by highlighting its Catholic tradition, and the opposition against sociology must also include various other antimodernist forces. Finally, one will have to consider the continuity of other non-Catholic but possibly equally antimodern forces in countries that were not coded as CATH = 1. Greece quite likely is a candidate for that. Instead of more speculations, the general argument here is to show that the results have pointed to the existence of multiple, possibly simultaneous, mechanisms that need to be clarified in new case studies to advance explanations of inhibited sociologies. Studying antisociological tendencies in Italy, Ireland, Belgium, and Greece, for example, under this pretext would already be a valuable lesson that justifies such comparative studies.

Another approach to the case studies is to ask which countries compare with others in ways that seemed implausible before. One example concerns rows 1 and 3 in the truth table (table 5), that is the Scandinavian countries and Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia respectively. Chronologically, what these six countries have in common is that their pattern of institutionalization unfolded rather late and quickly. The timing might be relevant and caused by the specific configurations of conditions discussed in the preceding text. The absence of an older sociological tradition might explain the relatively late timing, especially when compared to the large West European countries such as France or West Germany. Also, none of these countries were in asymmetric relations with a larger neighboring country that entails a “bandwagoning” mentality. In fact, the phases in which sociology has been institutionalized in these countries were all marked by an urgent need for social knowledge for massive state-run modernization projects with an open outcome. Neither Czechoslovakia nor Yugoslavia were democratic societies, but the degree of political openness was large enough that creative analyses of social relations were both possible and demanded by political elites. This episode was very short-lived in Czechoslovakia, where it ended abruptly in 1968, but it continued in Yugoslavia. Looking beyond the postwar period, we find additional similarities. The initial rationale for sociology to thrive was its assigned role in assisting major political projects of modernization in these countries. This role may help the discipline gain the social recognition that it strives for, but perhaps also brings sociology into a heteronomous relation with the “field of power” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2004: 87; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2009). Scandinavian sociology has been strongly entangled with the welfare state institutions that shape its intellectual orientation even now. The case of Denmark points to the danger of being too closely dependent on state institutions, illustrated by the episode of a total closedown and rebuilding of the discipline along the ideological lines of a neoconservative government in the 1980s (Kropp Reference Kropp2015). Similarly, Yugoslavia’s sociology successfully gained recognition from state authorities, but its social role was defined more closely to the cultural pole than to applied policy. In accordance with Yugoslavia’s self-proclaimed avant-garde position as the inventor of a new and unique path to socialism, its sociologists found fertile ground to develop one of the most dynamic scenes of leftist social thought, broadly defined, in the world. Its gnawing criticism of socialist realities in Yugoslavia also brought them into conflict with political elites in the 1970s, but its institutional position was too strong to bring it into real danger. From this perspective, sociology in Yugoslavia clearly compares better to Scandinavian cases than to any “Soviet-type” sociology (Duller Reference Duller, Adela and Victor2018).

Truth table row 2 represents a large and unsurprising group of well-established Western European nations with strong sociological traditions. Similarly predictable is the group covered by row 5, in which adverse political conditions inhibited sociology. Among this group, Hungary arguably deserves the most attention because of the considerable leeway scholars and intellectuals have found behind the scenes at different times. Looking back at a rich tradition (though with limited continuity), Hungarian social scientists have continuously produced interesting scholarship. Sociologists, however, received only limited support by the regime and, in contrast to reform economists, were in the longer run unable to find a position in which their knowledge was deemed policy-relevant and demanded by the political elite, even under comparably liberal conditions (Péteri Reference Péteri2016). One can hypothesize that strong intellectual prewar traditions, which usually entail an upper-middle-class background, have caused distrust and alienation between those embroiled in the tradition and ascending communist elites. Whether purged or not, historically well-established intellectual scenes in Central European communist countries tended to develop into hotbeds of dissident movements, suggesting deep resentment between old and new cultural and political elites. Only a police-state as extreme as the GDR could effectively produce loyal intellectuals, where a well-established intellectual elite had existed before Communist times (Connelly Reference Connelly1997; Jessen Reference Jessen1999; Joppke Reference Joppke1995; Torpey Reference Torpey1995).

Conclusions

Taking an institutional perspective on the history of sociology in 25 European countries during its dynamic phase of academic expansion in the postwar years, this article has explored different explanations for the successful institutionalization of sociology through systematic case comparison. Massive state-driven modernization projects responded to the historical circumstances of a devastated Europe after 1945. Though differing in forms and intensities, all European societies were in need of new ideas of social and political organization, and the ascending social sciences promised to deliver that. The universality of this promise was received within vastly different academic traditions, which calls for a comparative analysis.

This analysis has identified two groups of European countries of roughly the same size: a group of countries in which sociology could achieve the institutional premises that secured its academic and intellectual functioning within a relatively short time until the mid-to-late 1960s and a group of countries where this process was inhibited. This distinction has allowed for a discussion about the role of several explanatory conditions.

Against the conventional wisdom that sociology only thrives in liberal democracies, the most interesting results concern the explanation for sociologically unsuccessful democracies as well as sociologically successful nondemocracies. Among the former, two mechanisms have been outlined. The first is a mechanism of enticement. It refers to smaller countries that neighbor a significantly larger, culturally similar country and inhibits the need for developing their own institutions to produce social knowledge. The second shows the negative impact of an older sociological tradition in several European countries together with a strong presence of political Catholicism. Here, Catholic versions of social science have often established institutional structures that saw secular sociology as rivals and thus effectively hindered the latter’s institutional success for decades. Among the successful nondemocracies, communist regimes proved supportive of sociological institutions in phases of political liberalization and a quest for new paths toward socialism. These results are perhaps the most intriguing inasmuch as they indicate inroads for new theoretical angles to be explored in greater historical detail for individual national histories of sociology.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2021.37

Acknowledgments

The research leading to this article has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/20072013) under grant agreement no. 319974 (Interco-SSH). During the course of this project, at the Social Science History Association Conference 2016 in Chicago, and at various other occasions, I received valuable feedback and suggestions from Christian Fleck, Gustavo Sorá, Andrew Abbott, Johan Heilbron, Victor Karády, Marco Santoro, Rafael Schögler, Gisèle Sapiro, Marcus Morgan, Barbara Grüning, Thibaud Boncourt, and Zorica Siročić. I also acknowledge the detailed comments by two anonymous reviewers that have helped me, among other things, to make my methodical analysis more rigorous and transparent. Needless to say, all remaining flaws and errors are my own.