The implementation of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) in 2009 was seen as a watershed period; it was one of the biggest challenges and at the same time a great opportunity for the National Health Service (NHS) to reform its approach to patient care provided by junior doctors. Bringing the maximum working hours for junior doctors to 48 h per week required looking at new ways of working and new role development to ensure that service provision is maintained or enhanced, while at the same time fulfilling robust training requirements for both foundation and specialty trainees.

The EWTD is one of the health and safety legislations originally formulated in 1993. It came into force in 1998 for all doctors with the exception of trainees. A revision statement later included trainees, which came into force in August 2004. The hours were limited to 56 initially, with further reduction to 48 h per week by 2009. Reference Mukherjee and Nimmagadda1

Associated European Court judgments introduced further restrictions on working patterns of doctors. From August 2004, all time spent at work counted as work, in contradiction to the rest and work requirements of the new deal. Further, the Jaeger judgment specified that any compensatory rest must be taken immediately after a period of work. Reference Mukherjee and Nimmagadda1

Under the 2009 EWTD there is also an entitlement: Reference Brown and Bhugra2

-

• to a daily rest period of 11 uninterrupted hours

-

• each week to an uninterrupted day off of 24 h (or 48 uninterrupted hours in a fortnight)

-

• to a rest break of 20 min if the working day is longer than 6 h

-

• to 4 weeks of paid leave each year.

The objectives for implementing the EWTD included:

-

• improving patient safety

-

• enhancing trainee well-being

-

• a robust education and training environment

-

• an opportunity to provide better service for patients.

It is now 3 years since the implementation of the EWTD in the NHS, so it is timely to ask whether the introduction of the EWTD has lived up to its promise.

All of the psychiatry training posts in the Oxford Deanery have been compliant with EWTD regulations since 2009. This study was conducted to evaluate the views of trainees and trainers of the impact of the EWTD in achieving its stated objectives.

Method

The aim of this study was to gain a ‘snapshot’ of the prevailing views in both trainee and trainer groups in relation to postgraduate medical training directly related to EWTD implementation. To assess the perceptions from both trainees and trainers, two parallel versions of questionnaires were developed and administered to the two groups from across trusts in the Oxford Deanery School of Psychiatry. Broad agreement between the trainers’ and trainees’ ratings and responses could be construed as a true indicator of good training climate. On the other hand, it may be a reflection of the discordance between trainees’ and trainers’ perceptions of the prevailing training environment.

The study was conducted in two stages. The first stage (2009) was a qualitative survey of trainees and trainers in the Deanery on the positive and negative aspects of the EWTD to identify key areas. Based on these findings, a self-completed follow-up questionnaire (one for trainees and one for trainers, sent in 2011) including a mix of closed- and open-ended questions was designed to explore trainees’ and trainers’ views on the impact of the EWTD on patient safety, quality of care and quality of training (see the online supplement to this paper).

Using a convenience sampling method, 25 trainers attending an interview day for the Deanery to interview new core and advanced trainees were asked to complete the questionnaire; 20 questionnaires were returned (response rate 80%). Similarly, 21 trainees attending two randomly selected training events in different geographical areas of the Deanery (Oxford and Aylesbury) were asked to complete the trainees’ questionnaire; 19 completed forms were returned (response rate 90%).

Results

A total of 68% of trainees and 70% of trainers were aware of the main objective of the EWTD: to reduce the working hours of junior doctors to a maximum of 48 h per week.

Just over half of trainees (53%) believed that the quality of training was not compromised by implementation of the EWTD, whereas the majority of trainers (84%) believed otherwise.

Table 1 Summary of trainees’ and trainers’ opinion about the European Working Time Directive (EWTD)

| Area of interest | Positive, n (%) | Negative, n (%) | Unsure, n (%) | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact on quality of training | ||||

| Trainees | 10 (53) | 4 (21) | 5 (26) | 19 |

| Trainers | 1 (5) | 16 (84) | 2 (11) | 19 |

| Impact on workload | ||||

| Trainees | 7 (37) | 3 (16) | 9 (47) | 19 |

| Trainers | 0 (0) | 17 (85) | 3 (15) | 20 |

| Impact on quality of care and patient safety | ||||

| Trainees | 2 (11) | 8 (42) | 9 (47) | 19 |

| Trainers | 0 (0) | 16 (80) | 4 (20) | 20 |

| Overall impact of EWTD | ||||

| Trainees | 9 (53) | 5 (29) | 3 (18) | 17 |

| Trainers | 1 (5) | 18 (90) | 1 (5) | 20 |

Fifty per cent of trainees felt that there was a clear impact of the EWTD on their on-call experience, although 37% described it as positive and 16% believed that it had a negative impact. In contrast, the majority of trainers (85%) believed that the introduction of the EWTD had a negative impact on their own workload.

About half the trainees (47%) were unsure about any adverse outcome of the EWTD on the quality of patient care. Among trainees who had a clear opinion, most believed that the EWTD did not improve the quality of patient care (42%). The majority of trainers (80%), however, clearly believed that the introduction of the EWTD had a negative impact on the overall quality of patient care.

Just over half of trainees (53%) perceived the implementation of the EWTD as a positive change in clear contrast to the overwhelming majority of trainers (90%), who considered it to have a negative effect (Table 1).

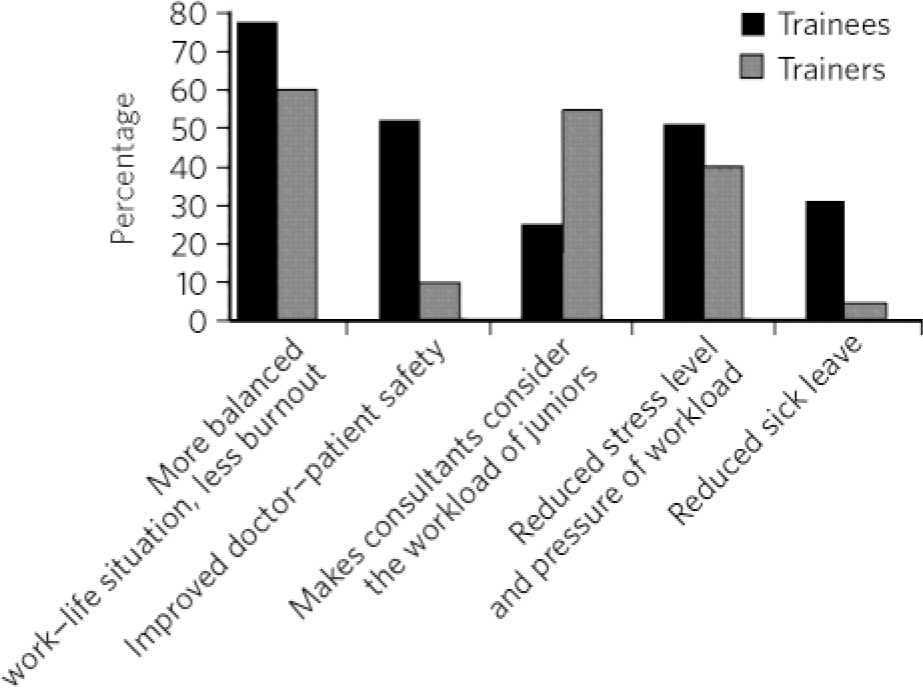

Both trainees and trainers considered that a more balanced work-life situation and less burnout was the most positive effect of the EWTD (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

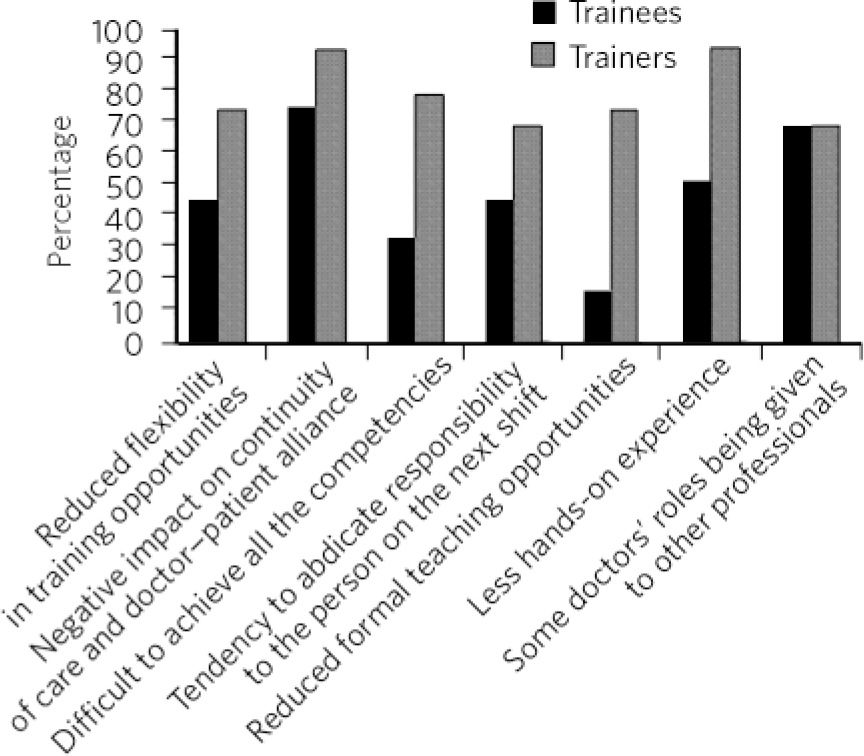

Most trainees and trainers (76% and 95% respectively) shared the opinion that the introduction of the EWTD had a negative impact on continuity of care and doctor-patient alliance, whereas almost all trainers (95%) believed that junior doctors had less hands-on experience since the introduction of the EWTD. Thirty-five per cent of trainers also believed that the introduction of the EWTD led to an increase in their workload and consequent burnout (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Discussion

The implementation of the EWTD in 2009 led to significant changes to the working hours and working patterns (shifts) for trainee doctors. These changes have challenged the traditional apprenticeship model of postgraduate training, leading to a schism between maintaining quality of training and the need to deliver it in a shortened duration brought on by the constraints imposed by new working patterns. The key to resolving this conflict lies in ensuring effective and efficient postgraduate training as far as practical.

There has been a remarkable heterogeneity in findings about the EWTD in the literature which could be the reflection of shortfalls in methodology of studies or the true difference among the effects of the EWTD on different branches of medicine. Before the implementation of the EWTD, it is not unthinkable that longer shifts and physical tiredness could have significantly increased the risk of mistakes made by a surgeon or an accident and emergency doctor; Reference Cappuccio, Bakewell, Taggart, Ward, Sullivan and Edmunds3-Reference Collum, Harrop, Stokes and Kendall6 however, after the introduction of the EWTD, for a psychiatrist or public health trainee it is the lack of experience which increases the risk of mistakes most. Reference McCartney, Dunbar, Morling, Johnman and Gilmour7

Table 2 Summary of the positive impacts of the European Working Time Directive in trainees’ and trainers’ opinions

| Positive impact | Trainees n (%) |

Trainers n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| More balanced work-life situation, less burnout | 15 (79) | 12 (60) |

| Improved doctor-patient safety | 10 (53) | 2 (10) |

| Makes consultants consider the workload of juniors | 5 (26) | 11 (55) |

| Reduced stress level and pressure of workload | 10 (52) | 8 (40) |

| Reduced sick leave | 6 (32) | 1 (5) |

Fig 1 Discrepancy between trainees and trainers on the positive impacts of the European Working Time Directive.

Likewise, during the early years post-implementation of the EWTD, some authors predicted grave implications for psychiatrists at all levels, Reference Alikhan8,Reference McLernon, Coccia and Patel9 including extra workload for consultants. Reference Harrison10 However, a research project commissioned by the Department of Health to assess the impact of the EWTD on postgraduate medical education strongly suggested the positive effects of the EWTD on the education and training climate. Reference Davies, Clarke and Farrell11

In maintaining training effectiveness, the prevailing training climate is important as it has been found that the context in which training takes place sets motivation, expectations and attitudes. Reference Quiñones and Ehrenstein12 The importance of the training climate was highlighted in a review of training progress across organisations, which concluded that ‘many training programmes fail to reach their goals because of organisational constraints and conflicts’. Reference Salas and Cannon-Bowers13 Training motivation and outcomes are based on both situational characteristics such as organisational climate and individual characteristics such as self-efficacy. Reference Colquitt and Lepine14

Table 3 Summary of the negative impacts of the European Working Time Directive in trainees’ and trainers’ opinions

| Negative impact | Trainees n (%) |

Trainers n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced flexibility in training opportunities | 8 (47) | 15 (75) |

| Negative impact on continuity of care and doctor-patient alliance | 13 (76) | 19 (95) |

| Difficult to achieve all the competencies | 6 (35) | 16 (80) |

| Tendency to abdicate responsibility to the person next on shift | 8 (47) | 14 (70) |

| Reduced formal teaching opportunities | 3 (18) | 15 (75) |

| Less hands-on experience | 9 (53) | 19 (95) |

| Some doctors’ roles being given to other professionals | 12 (70) | 14 (70) |

| Decreased salary | 7 (41) | NA |

| Burnout for senior doctors | NA | 7 (35) |

NA, not applicable.

Fig 2 Discrepancy between trainees and trainers on the negative impacts of the European Working Time Directive.

Although the terms ‘climate’ and ‘culture’ are often used interchangeably, one review Reference Cox and Flin15 made a distinction in terms of level of abstraction and their permanence. The authors concluded that the training climate provides a measure of the prevailing mood within the organisation and is more of a ‘snapshot’ at any given time, and can be understood as a manifestation of culture. The training climate has an impact on both ‘on the job’ training (i.e. training that occurs as part of day-to-day clinical activities) and ‘training transfer’ (i.e. the extent to which learning from formal courses is transferred to clinical practice), as the interaction between trainee characteristics and the transfer environment produces differences in performance. Reference Smith-Jentsch, Salas and Brannick16

Main study findings

The strength of the trainers’ views towards the EWTD in our study in contrast with the Department of Health report is striking. Trainers in psychiatry in the Oxford Deanery held a very negative opinion about the implementation of the EWTD, whereas trainees had a more favourable view. It is possible that with the benefit of hindsight, trainers were in a better position to compare the effect of the changes before and after introduction of the legislation. Equally, their view might be biased due to their negative perceptions from changes to their workload and burnout.

The study suggests that the EWTD may not have been totally successful in achieving all of its stated objectives. From our results, it is clear that the training environment has clearly shifted somewhat in the context of the EWTD, with different consequences for trainees and trainers - the two main stakeholders. This is reflected in the increased role conflict experienced by trainers as they aim to meet both service requirements and their professional responsibility and commitment to providing good-quality training. From the perspective of maintaining a decent training climate for trainees and trainers alike, it is very important to resolve the tensions between the two stakeholders. Although the biggest concern raised by trainers was that of fragmentation of service provision, resulting in trainees’ inability to follow-up patients and learn through such experiences, it is crucial that this does not have a negative impact on their enthusiasm to teach and train. The trainees on their part should show more initiative in seeking constructive feedback from their trainers, build on their experience and skills gained in training, and contribute to a structured and more productive handover to their colleagues. In our opinion, these areas should be explored further to bring a more convergent approach from both stakeholders in achieving just that.

We appreciate that there are some limitations regarding generalisability of our findings. It is possible that specific regional factors may have influenced the attitudes of trainers and trainees towards the EWTD. The EWTD also had a broader impact on nursing staff, patients and other professionals. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting our findings.

We believe further studies on different samples of healthcare professionals and service users, incorporating objective indicators of patients’ safety, quality of training and quality of care (e.g. number of untoward incidents involving junior doctors before and after the introduction of the EWTD), would help to clarify the wider impact of the EWTD. We suggest that by disentangling the different elements of the EWTD (e.g. not working 7 consecutive days, not working more than 13 h a day and not working more than 48 h a week) and their impact on the stated objectives in future studies would provide a more robust view of the overall impact of the EWTD. This would enable a more informed debate on the necessity or otherwise of revising or amending aspects of the EWTD in the UK in the future.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.