Tuberculosis (TB) remains a common and deadly disease globally( Reference Lyons and Stewart 1 ). In 2015, there were an estimated 10·4 million incident cases of TB, and 1·8 million people died from the disease( 2 ).

In Taiwan, of all notified infectious diseases, TB has been the most prevalent for decades( 3 ). Since 2006, Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has adopted a directly observed therapy, short course (DOTS) programme to achieve a successful treatment rate of 85 % and halve TB incidence by 2015. Since then, the success rate for TB treatment improved only slightly from 64·1 % in 2005 to 70·4 % in 2012. Mortality among TB patients accounted for 81·8 % of the unsuccessful cases of TB treatment( 3 ).

BMI is a popular and useful tool to evaluate the nutritional status of an individual( Reference Kim, Kim and Kwon 4 ). Nutrition disequilibrium (e.g. underweight or obesity) can impair the immune system (e.g. T cell suppression)( Reference Schaible and Kaufmann 5 ) and could therefore affect the treatment outcome in TB patients. Although many studies have evaluated the risk factors for mortality in TB patients( Reference Waitt and Squire 6 ), the association between BMI and mortality in this population has not been studied extensively, and the existing evidence is inconsistent( Reference Kim, Kim and Kwon 4 , Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 – Reference Lai, Lai and Yen 12 ). Some studies reported that lower BMI was significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality among TB patients( Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 – Reference Yen, Chuang and Yen 10 , Reference Lai, Lai and Yen 12 ), whereas another two found no such an association( Reference Kim, Kim and Kwon 4 , Reference Kwon, Kim and Song 11 ). Moreover, one study found that overweight was a protective factor for mortality among TB patients( Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 ).

According to the WHO, mortality in TB patients is defined as death for any reason during treatment( Reference Balabanova, Drobniewski and Fedorin 13 ). However, a number of TB patients die of cerebrovascular disease or malignancy instead of TB. Although many studies have evaluated the factors associated with mortality in TB patients, few studies have determined the predictors of TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality( Reference Waitt and Squire 6 ).

According to the CDC guidelines, TB patients should be administered effective drugs for at least 6 months( 14 ). The timing of death in TB patients varies during treatment; for example, many patients die within the first 8 weeks of treatment, whereas others die later( Reference Jonnalagada, Harries and Zachariah 15 ). Although few studies have examined the prognostic factors for TB with respect to the timing of death( Reference Waitt and Squire 6 ), a recent report found that predictors of mortality varied according to timing of death in TB patients( Reference Yen, Yen and Shih 16 ).

Developing effective interventions to improve TB outcomes requires a better understanding of the factors associated with cause-specific mortality and timing of death. Thus this population-based study aimed to investigate the impact of BMI on TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality with respect to different timing of death.

Methods

Study population and data source

This retrospective cohort study utilised TB surveillance data from Taipei, Taiwan. In Taipei, TB cases must be reported to the Taipei TB Prevention Center within 7 d of diagnosis. This study included Taiwanese adults (age ≥18 years) diagnosed with TB in Taipei during the period 2012–2014. TB was defined based on clinical and/or laboratory findings( Reference Wang, Chang and Su 17 ). Clinical findings included symptoms (e.g. cough, wasting, prolonged fever) consistent with TB and exclusion of other differential diagnoses based on diagnostic evaluation( Reference Wang, Chang and Su 17 ). Laboratory definitions included M. tuberculosis isolated from a clinical specimen or acid-fast bacilli (AFB) demonstrated in a clinical specimen from patients with clinical symptoms consistent with TB. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospitals (TCHIRB- 10505112-E).

Data collection

When TB patients are reported to the Taipei TB Prevention Center, trained case managers use a structured questionnaire to interview patients about their sociodemographic characteristics, clinical findings, and underlying diseases. Sociodemographic factors include age, sex, BMI, marital status, education level, smoking status, alcohol use and unemployment. TB patients in Taipei are required by law to be monitored until treatment success, death or lost to follow-up. For the purpose of monitoring treatment response, case managers followed up all TB cases by phone or in person once every other week.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of interest was treatment outcome, which was categorised as successful treatment or mortality. Mortality was classified as TB-specific or non-TB-specific according to the cause of death. TB-specific death was defined as an underlying cause of death due to TB in the Taiwan Death Certification Registry (International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9: A010–A018; ICD-10: A15–A19)( 18 ). Non-TB-specific death was defined as any underlying cause of death other than TB. By law, a death certificate must be registered according to ICD 9 or 10 within 30 d after a patient dies in Taiwan. Because trained medical registrars review all death certificates at the central office of the National Death Certification Registry, the cause-of-death coding in Taiwan is considered very accurate( Reference Lu, Lee and Chou 19 ).

Mortality was also categorised as early or late according to the timing of death. Early death was defined as death within the first 8 weeks of TB treatment, and late death was defined as mortality later than 8 weeks after the start of TB treatment but before completion of such therapy( Reference Nguyen, Hamilton and Xia 20 ).

Main explanatory variable

The main explanatory variable was BMI (kg/m2), which was recorded when the case managers interviewed TB cases at the time of TB notification to the Taipei TB Prevention Department. According to the WHO International Classification of adult body weight, BMI was categorised as underweight (<18·5 kg/m2), normal (18·5–24·9 kg/m2) or overweight (≥25 kg/m2)( 21 ).

Control variables

Control variables included sociodemographic factors (education level, smoking status), clinical findings (AFB-smear status, TB culture, cavities on chest radiograph (CXR), pleural effusion, extrapulmonary TB), comorbidities (malignancy, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease) and mode of TB treatment. Education level was categorised as uneducated, elementary school, high school, or university or higher. Smoking status was categorised as never, quit smoking and current smoker. The mode of TB treatment was classified as directly observed treatment (DOT) or self-administered treatment. DOT was defined as administration of antituberculosis medication directly supervised by trained public health observers( Reference Jasmer, Seaman and Gonzalez 22 ).

Statistical analysis

First, the sociodemographic characteristics are presented according to BMI category. The two-sample t test was used for comparisons of continuous data between groups. Categorical data were analysed using the Pearson χ 2 test, where appropriate.

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was conducted using all-cause mortality v. treatment success as the outcome with BMI category as the main explanatory variable. The multinomial Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify the factors associated with cause-specific mortality (TB-specific v. non-TB-specific mortality) and timing of death (early v. late death). To investigate the factors associated with cause-specific mortality with respect to timing of death, the treatment outcome in TB patients was classified into five categories: TB-specific death within the first 8 weeks of treatment, TB-specific death later than 8 weeks of treatment, non-TB-specific death within the first 8 weeks of treatment, non-TB-specific death later than 8 weeks of treatment and treatment success. Then multinomial Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to determine the impact of BMI on TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality with respect to different timing of death. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95 % CI are reported, to indicate the strength and direction of associations. All data management and analyses were performed using the SAS 9.4 software package (SAS Institute).

Results

Characteristics of patients with tuberculosis

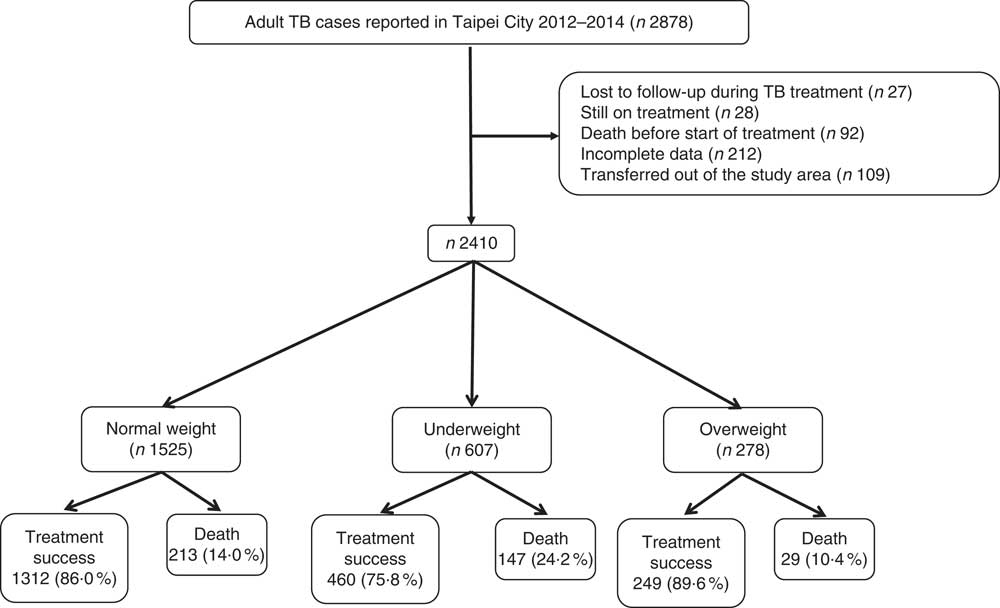

A total of 2878 TB cases were reported to the Taipei TB Prevention Department in 2012–2014. Of these, ninety-two died before starting TB treatment, twenty-seven were lost to follow-up during treatment, twenty-eight was still on treatment at the time of this study, 212 had incomplete data and 109 had transferred out of Taipei city (Fig. 1). The remaining 2410 cases were included in the subsequent analysis; the mean age was 64·5 (sd 20·2) years, and 67·1 % were men (Table 1). According to the WHO BMI definition, 25·2, 63·3 and 11·5 % of the patients were classified as underweight, normal weight or overweight, respectively. During the study follow-up period, 145 (14·2 %) deaths occurred in normal weight patients, 99 (24·4 %) deaths occurred in underweight patients, and 19 (10·3 %) deaths occurred in overweight patients (Table 1). Table 1 also shows the distribution of mortality according to cause-specific and timing of death.

Fig. 1 Study population. TB, tuberculosis.

Table 1 Characteristics of tuberculosis patients; by BMI category (Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations)

DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; TB, tuberculosis; AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CXR, chest radiograph; DOT, directly observed treatment.

Associations between BMI and all-cause mortality

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify independent risk factors for all-cause mortality in TB patients (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, clinical findings and comorbidities, the risk of all-cause mortality was significantly higher in underweight patients (AHR 1·57; 95 % CI 1·26, 1·95; P<0·001) than in normal weight patients. Overweight was not significantly associated with all-cause mortality. Other risk factors for all-cause mortality included age ≥65 years (AHR 2·98; 95 % CI 2·10, 4·23), male sex (AHR 1·39; 95 % CI 1·08, 1·78), unemployment (AHR 2·30; 95 % CI 1·43, 3·68), end-stage renal disease (AHR 2·24; 95 % CI 1·54, 3·25), malignancy (AHR 2·68; 95 % CI 2·08, 3·46), AFB-smear positivity (AHR 1·56; 95 % CI 1·20, 1·95), TB-culture positivity (AHR 1·38; 95 % CI 1·01, 1·87) and pleural effusion on CXR (AHR 1·61; 95 % CI 1·23, 2·13). Also, factors associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality included university or higher education (AHR 0·59; 95 % CI 0·40, 0·88) and DOT (AHR 0·62; 95 % CI 0·41, 0·91).

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for all-cause mortality in tuberculosis (TB) patients; Taipei; Taiwan (2012–2014) (Numbers and percentages; hazard ratios (HR), adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95 % confidence intervals)

DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; CXR, chest radiograph; DOT, directly observed treatment.

* P<0·05, ** P<0·01, *** P<0·001.

Association between BMI with tuberculosis-specific and non-tuberculosis-specific mortality

Table 3 shows the results of the multinomial Cox regression analysis of factors associated with TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality. Underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of TB-specific (AHR 1·85; 95 % CI 1·03, 3·33; P=0·040) and non-TB-specific mortality (AHR 1·52; 95 % CI 1·19, 1·95; P<0·001) during treatment. However, overweight was not significantly associated with TB-specific or non-TB-specific death during treatment.

Table 3 Associations of BMI with tuberculosis (TB)-specific and non-TB-specific deathFootnote † (Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95 % confidence intervals)

DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CXR, chest radiograph; DOT, directly observed treatment.

* P<0·05, ** P<0·01, *** P<0·001.

† Reference is successfully treated individuals.

‡ Adjusted for BMI, age, sex, marital status, education level, unemployment, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, malignancy, TB relapse, AFB smear, TB culture, cavities on CXR, extrapulmonary TB and directly observed treatment.

Association between BMI and early or late death during tuberculosis treatment

Table 4 shows the results of the multinomial Cox regression analysis of factors associated with early or late death during TB treatment. After controlling for potential confounders, underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of early death (AHR 1·87; 95 % CI 1·38, 2·55; P<0·001), but not late death. Moreover, overweight was not significantly associated with early or late death during TB treatment.

Table 4 Associations of BMI with early and late death in tuberculosis (TB) patientsFootnote † (Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95 % confidence intervals)

DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CXR, chest radiograph; DOT, directly observed treatment.

* P<0·05; ** P<0·01; *** P<0·001.

† Reference is successfully treated individuals.

‡ Adjusted for BMI, age, sex, marital status, education level, unemployment, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, malignancy, TB relapse, AFB smear, TB culture, cavities on CXR, extrapulmonary TB and directly observed treatment.

Association between BMI and cause-specific mortality with respect to the timing of death

Table 5 shows the results of the multinomial Cox regression analysis for the association between BMI and cause-specific mortality in relation to the timing of death. After adjusting for age, sex, clinical findings, and comorbidities, underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of TB-specific (AHR 2·23; 95 % CI 1·09, 4·59; P=0·029) and non-TB-specific mortality (AHR 1·81; 95 % CI 1·29, 2·55; P<0·001) within the first 8 weeks of treatment, but not significantly associated with TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality later than 8 weeks after treatment initiation. Also, overweight was not significantly associated with TB-specific or non-TB-specific death within or later than 8 weeks after treatment initiation.

Table 5 Multinomial regression for the association between BMI and cause-specific mortality in relation to timing of death in tuberculosis (TB) patientsFootnote † (Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95 % confidence intervals)

* P<0·05, *** P<0·001.

† Reference is successfully treated individuals.

‡ Variables included: age, sex, clinical findings and comorbidities.

Discussion

In this cohort study of 2410 Taiwanese adults with TB in 2012–2014, overall mortality was 14·0 %. After controlling for potential confounders, underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality, whereas overweight was not. When cause-specific death was considered, underweight was associated with an increased risk of either TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality during TB treatment. When considering both cause-specific mortality and timing of death, underweight only significantly increased the risk of TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality within the first 8 weeks of treatment, but was not significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality later than 8 weeks after treatment initiation.

The association of BMI with TB outcome was inconsistent in previous reports( Reference Kim, Kim and Kwon 4 , Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 – Reference Lai, Lai and Yen 12 ). Four studies found that lower BMI was significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality among TB patients( Reference Bhargava, Chatterjee and Jain 8 – Reference Yen, Chuang and Yen 10 , Reference Lai, Lai and Yen 12 ), with one study reporting that greater BMI (per unit increase) was significantly associated with a lower risk of mortality( Reference Bhargava, Chatterjee and Jain 8 ). In contrast, another two studies found no differences in the risk of mortality based on BMI (<18·5 v. ≥18·5 kg/m2)( Reference Kim, Kim and Kwon 4 , Reference Kwon, Kim and Song 11 ). Moreover, Hanrahan et al.( Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 ) found that underweight significantly increased the risk of mortality among patients with HIV and TB coinfections, whereas obesity and overweight were protective. The present study found that overweight was not significantly associated with the risk of mortality, but underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of either TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality during treatment. Furthermore, the main impact of underweight on mortality occurred within the first 8 weeks of TB treatment. The findings in this study indicated that underweight was an independent risk for TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality, particularly within 8 weeks after the start of TB treatment.

Although underweight was significantly associated with a higher risk of TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality within the first 8 weeks of TB treatment, the association was NS after the initial 8 weeks of TB treatment. Higher early mortality among underweight TB patients may be due to lower immunity and more severe TB infection in this population. Underweight can suppress lymphocyte stimulation and reduce secretion of Th1 cytokines (e.g. IL-2, TNF-α and interferon-γ)( Reference Cegielski and McMurray 23 ), which could cause more severe TB infection. In malnourished animals, macrophages produce more transforming growth factor β, which further suppresses T cells and causes severe TB disease( Reference Dai and McMurray 24 , Reference Dai and McMurray 25 ). Animal studies have also shown that malnourished mice have an impaired immune system (e.g. reduction of reactive N intermediates) in response to Mycobacterium infection( Reference Chan, Tian and Tanaka 26 ). Moreover, malnourished animals have higher bacterial burdens with TB infection and die earlier of infection( Reference Chan, Tian and Tanaka 26 ).

This study showed that overweight TB patients had a lower risk of all-cause mortality than normal weight patients (10·4 v. 14·0 %), although this was not statistically significant. Although this association of interest has not been extensively studied, a prior study found that overweight or obesity was protective against mortality in patients with HIV–TB co-infection( Reference Hanrahan, Golub and Mohapi 7 ). Patients with TB who experience a mild or moderate increase in BMI may consume more protein and energy on a daily basis, which could result in more robust immune function and reduce mortality. However, more studies are needed to evaluate the impact of overweight or obesity on all-cause and cause-specific mortality as well as timing of death in TB patients.

This study found that DOT was significantly associated with a lower risk of mortality after controlling for BMI and other potential confounders. In Taipei’s DOTS programme, each DOT observer monitors five to fifteen TB patients on average( 3 ). DOT observers interview patients regarding their TB symptoms and complications of treatment under the supervision of public health nurses. When TB patients on DOT have, for example, worsened dyspnea, the public health nurses contact doctors to arrange hospital visits. DOT has been recommended for TB patients to improve their adherence to treatment( Reference Frieden and Sbarbaro 27 ). Our study suggests that DOT programme should be applied to all TB patients to further reduce mortality.

The strength of this study is that all eligible TB patients were included in the analysis; therefore, the sample size was not based on the considerations of statistical power. However, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this citywide population-based study. First, in this retrospective cohort study, some important patient information (e.g. intravenous drug use, chronic lung disease and psychiatric disorders) was not available. Second, 25·4 % of the TB cases were identified based on clinical diagnosis rather than by AFB smear or culture, which could have resulted in over-diagnosis of TB. However, this is less likely in this study because the Taipei TB Control Department holds an expert committee monthly to discuss the uncertain diagnosis of TB cases( 3 ). Third, the information regarding BMI among TB patients were self-reported, and therefore subject to recall bias. Moreover, this study only measured BMI at baseline. As BMI can change during TB treatment( Reference Vasantha, Gopi and Subramani 28 ), more studies are needed to determine the time-varying effect of BMI on mortality in TB patients. Finally, the external validity of our findings may be a concern because all the participants were Taiwanese. The generalisability of our results to other non-Asian ethnic groups thus requires further verification. Nevertheless, our findings suggest new avenues for future research.

Conclusions

In the present study, mortality was high in TB patients in Taipei, Taiwan, in 2012–2014. After controlling for other covariates, underweight was significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality during TB treatment, whereas overweight was not. For cause-specific mortality, underweight was associated with an increased risk of either TB-specific or non-TB-specific mortality during treatment. With the simultaneous consideration of cause-specific mortality and timing of death, underweight only significantly increased the risk of TB-specific and non-TB-specific mortality within the first 8 weeks of treatment, but was not significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality after the initial 8 weeks of treatment. The findings in this study indicate that underweight increases the risk of early death in TB patients during the treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to registered nurses Jen-Chieh Hsiao and Miao-Yun Chen for interviewing the subjects and reviewing their medical records.

This study was funded.

Y.-F. Y., F.-I. T., B.-L. H., Y.-J. L. substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study, data analysis, data interpretation and the drafting of the manuscript. Y.-F. Y. substantially contributed to data acquisition and interpretation of the results. Y.-F. Y., F.-I. T., B.-L. H., Y.-J. L. all approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.