Background

Canada’s centuries-long history of colonization with forced displacement of Indigenous peoples’ communities tells a story of domination, discrimination, and assimilation (Ballard, Reference Ballard, Mulé and DeSantis2017; Denov & Campbell, Reference Denov and Campbell2002; Martin, Thompson, Ballard, & Linton, Reference Martin, Thompson, Ballard and Linton2017; Wilson, Rosenberg, & Abonyi, Reference Wilson, Rosenberg and Abonyi2011). Forced displacement in Canada has occurred since European contact vis-a-vis the British North America Act of 1867, the signing of the Numbered Treaties 1-11 starting in 1871, and the Indian Act of 1876, where their purpose was to remove the First Nations to make way for settlers and development. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) proclaimed that forced displacement must be viewed within the broader process of dispossession and displacement that is known to have lingering impacts on the cultural, spiritual, social, economic, and political aspects of peoples’ lives.

Forced displacement has multiple, negative effects on Indigenous people (Burns, Reference Burns2006; Waldram, Reference Waldram1988). For example, the Sayisi Dene experienced violent deaths, alcoholism, racism, starvation, and homelessness after displacement from their traditional caribou hunting grounds in Northern Manitoba in the mid-1950s (Bussidor & Bilgen-Reinart, Reference Bussidor and Bilgen-Reinart1997). Evidence indicates strong associations between historical losses (e.g., loss of land, loss of language) and affective outcomes including guilt, hopelessness, despair, anger, substance abuse, and depression (Walls & Whitbeck, Reference Walls and Whitbeck2012). In particular, Walls and Whitbeck (Reference Walls and Whitbeck2012) investigated the intergenerational consequences of forced displacement in four American Indian communities and four First Nations communities in Canada by collecting survey data from 507 youths and their biological mothers. These researchers concluded that the overarching government relocation policies and displacement elicited harmful health effects in three generations of families residing on or near the eight impacted reserves. Outcomes of forced displacement included intergenerational substance abuse, depressive symptoms, ineffective parenting skills, and delinquent behaviour in youth.

Forced Displacement Due to a Human-Made Flood in Manitoba in 2011

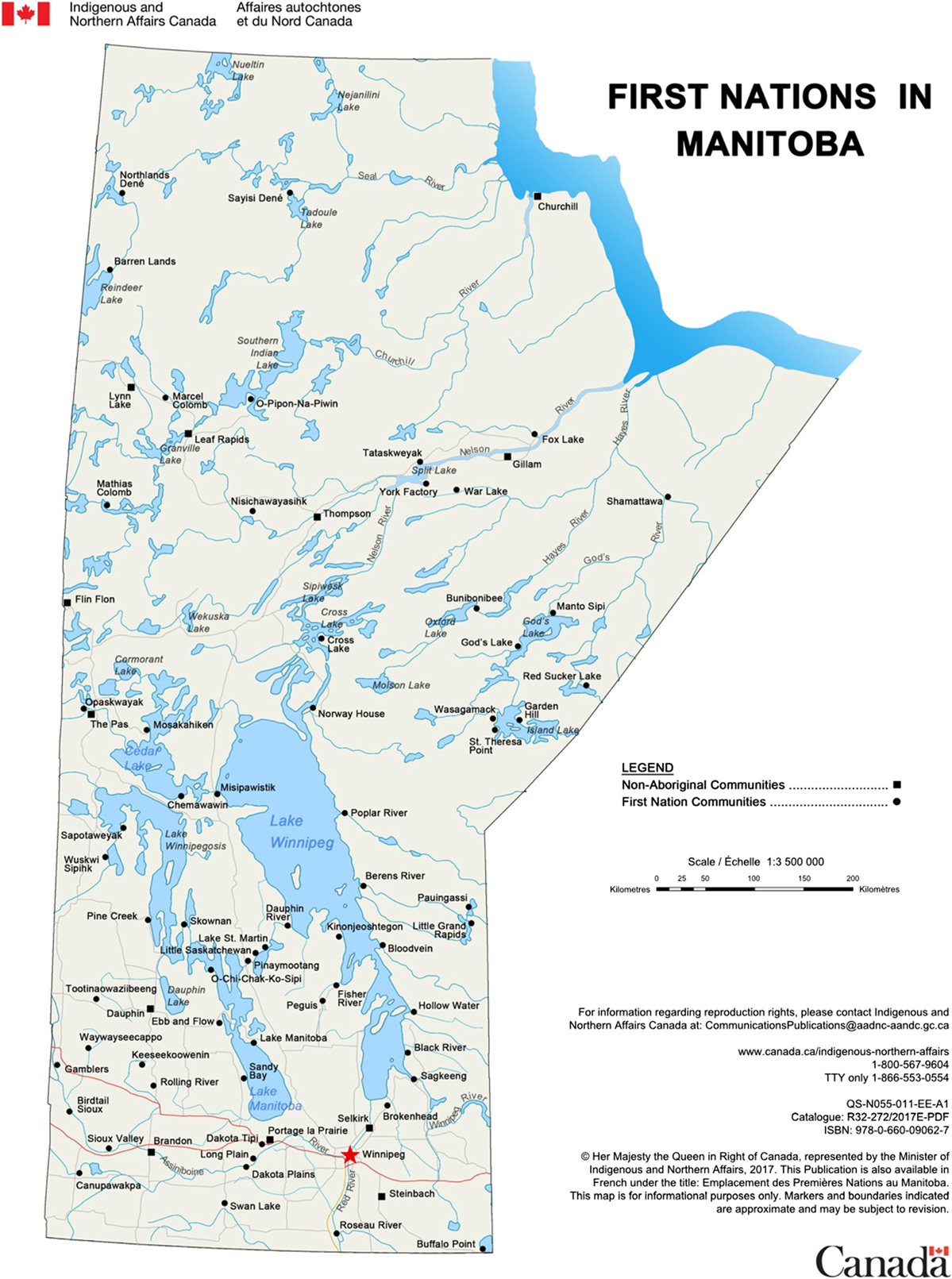

In the spring of 2011, in the Interlake region of Manitoba, 17 First Nation communities situated downstream from the Fairford Dam experienced a human-made flood and an emergency evacuation. “Manitoba decided to spare Winnipeg from the effects of the “superflood” – the largest spring runoff in provincial history – by diverting water into several northern native centres. Residents were rushed to Winnipeg thinking they’d be back in weeks, if not days” (Lum, Reference Lum2012, para. 3). Federal and provincial government policies were enacted to control and disempower five of the 17 communities: Pinaymootang, Little Saskatchewan, Lake St. Martin, Lake Manitoba, and Dauphin River First Nations (see Figure 1). Provincial government officials decided to save the City of Winnipeg and the upstream inhabitants by sacrificing the downstream residents – the First Nations.

Figure 1: Map showing the location of Lake St. Martin, Manitoba, and the location of the First Nation communities. Reprinted from Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada: Location of First Nations in Manitoba, by Government of Canada, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100020558/1100100020563. Copyright 2017.

The provincial government’s decision to flood this region resulted in multiple, negative ripple effects on these First Nations’ well-being (Ballard, Reference Ballard, Mulé and DeSantis2017; Ballard, Thompson, & Klatt, Reference Ballard, Thompson and Klatt2012; Ballard & Thompson, Reference Ballard and Thompson2013; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Thompson, Ballard and Linton2017; Thompson, Ballard, & Martin, Reference Thompson, Ballard and Martin2014). The human-made flood affected the health, social, cultural, political, environmental, and economic well-being of these First Nations (Ballard, Reference Ballard, Mulé and DeSantis2017; Ballard & Thompson, Reference Ballard and Thompson2013; Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Thompson and Klatt2012; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ballard and Martin2014). The human-made flood and forced displacement created devastating effects such as premature deaths, worsening chronic illnesses, depression, and loneliness (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Thompson, Ballard and Linton2017; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ballard and Martin2014). To date, most of these First Nation community members remain displaced, homeless, and landless with many evacuees residing in temporary housing in Winnipeg.

The Need to Hear the Elders’ Voices

Elders’ willingness to transmit accumulated wisdom and knowledge to other community members is a critical component of whether an individual is viewed as having a positive aging process (Collings, Reference Collings2001; Edge & McCallum, Reference Edge and McCallum2006; Wilson, Rosenberg, Abonyi, & Lovelace, Reference Wilson, Rosenberg, Abonyi and Lovelace2010). Edge and McCallum (Reference Edge and McCallum2006) held national and regional gatherings with 20 Métis seniors, Elders, and healers across Canada. These gatherings identified the intersection between history, culture, and language with health, healing, and wellness needs.

This article highlights how a qualitative study with a participatory framework addressed the need for reconciliation and healing following the 2011 human-made flood. The design was similar to previous studies that incorporated participatory frameworks to honour and facilitate the engagement of First Nations (Martin, Yurkovich, & Anderson, Reference Martin, Yurkovich and Anderson2015).

Given that Elders from First Nations communities are respected for their wisdom (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Rosenberg, Abonyi and Lovelace2010), the primary objective of this qualitative study was to document the Elders’ perspectives about strategies to heal from the human-made flood including how to reconcile and move forward. The purpose of this project was to document and record Pinaymootang, Little Saskatchewan, Lake St. Martin, Dauphin River, and Lake Manitoba First Nations Elders’ strategies to heal from the 2011 flood and forced displacement. It was important to hear from the Elders and document how they defined “maziaya” (not well/not healthy) and “minoaya” (well-being/healthy). Maziaya and minoaya are Anishinaabe mowin words. Documenting these stories and having the Elders share their experiences and providing advice is a form of healing for the Elders and for all the communities in the Interlake Reserves Tribal Council (IRTC) and other areas.

Methods

This project acquired approval from a research ethics board at the University of Manitoba. The IRTC partnered with the first author (MB) to facilitate a two-day Elders gathering. Elders were invited to share advice on how to heal and move forward from the 2011 human-made flood and forced displacement. Health directors from the IRTC communities organized the Elders gathering, which was held in 2015. More than 200 individuals attended the two-day gathering in a large meeting room located in a central hotel in Winnipeg. Representatives from the Canadian Red Cross, Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, and Southern Chiefs Organization also attended.

The IRTC and the research team relied on an “emic” or insider’s approach, which supported the collection and analysis of detailed accounts of ways to heal from the impacts of the flood and forced displacement from the perspective of the Elders. A qualitative approach within a participatory framework was used. During the gathering, Elders were invited to share their perspectives about strategies to heal and move forward using several formats. We used purposive sampling with this inclusion criterion: an Elder from a First Nation community within the IRTC. We also conducted small and large group discussions. All attendees were invited to answer key questions in small groups. Answers were documented in English on flip charts. Individuals from each small group shared their small group’s answers with all attendees in a large group discussion.

With respect to the oral tradition and language, another data source was semi-structured interviews with Elders that were digitally recorded on video. Following acquisition of a signed informed consent, the first author (MB) conducted semi-structured interviews in a private location with 23 Elders, who were compensated with a cash honorarium for their participation. We used a semi-structured interview guide. Examples of questions included the following: (a) Would you like me to conduct the interview in English or Ojibway? (b) Tell me about your experience of being evacuated from your home/community in 2011; (c) What are the next steps in moving forward? and (d) How can we heal? Video-recordings were translated into English and transcribed verbatim by the first author (MB). The small groups’ flip chart answers were transferred into a Microsoft Word document.

The 23 transcripts and small groups’ answers were read and reread to facilitate the process of thematic analysis. Authors Ballard and Martin analysed the data independently and then met to dialogue about emerging themes and subthemes.

During the course of the 2-day gathering, counsellors were available to assist the participants if needed. The Elders showed great emotion as they talked about their experiences (available at https://manitobafloodhealingvoices.com/). This particular type of methodology (where Elders were interviewed, one-on-one, via video-recordings) is particularly important because it incorporates tradition and technology. The participants were familiar with the interviewer and carried on the oral history and oral tradition with which knowledge and stories are passed on orally via video camera.

Findings: Reconciling with ‘Minoayawin’

Of the 23 video-recorded interviews and small- and large-group discussions, the overarching theme was identified as “reconciling with minoayawin”. The Elders shared stories about healing, listening to one another, forgiving, and reconciling with strategies to move forward. The Elders shared poignant and emotional accounts of how they dealt with the flood. In the following section, we present the subthemes and Elders’ recommendations for achieving minoayawin, beginning with the Elders’ definition of “maziaya”. It was important to decipher maziaya (meaning not well/not healthy) and what being unhealthy meant to the Elders, and what contributed to not being well before proceeding to their definition of well-being, in order to gain a greater understanding of health and well-being.

Elders’ Definition of ‘Maziaya’

Maziaya was described in terms of profound grief related to multiple losses. When the initial emergency evacuation occurred in 2011, many Elders assumed that they could return home after a few weeks. Prolonged displacement and uncertainty about returning home have compounded the grief in the ensuing years.

‘There Was A Lot of Hurt When We Left Our Homes’

Elders identified that many evacuees continue to suffer from deep trauma with multiple, significant losses and high stress and anxiety. One Elder stated:

I lost my husband five years ago and my son just a year ago, that was hard to lose a loved one. The reason why my husband died is he was frustrated with what we are going through. He wanted to go home and store up all our things, our equipment but he couldn’t make it. We have been through a lot. My husband and I used to have a farm. We had lots of cattle; we used to raise pigs, hens, geese.

Elders expressed that many evacuees felt that they could no longer fulfill their assigned roles in life – their vision and purpose of why they were created. With so little hope, depression and suicide ensued. Elders, confined to the small space of a hotel room, reported being so depressed that they could not get out of bed.

Elders acknowledged that mental health concerns greatly increased for many evacuees. Elders shared experiences of distress and anxiety as a result of the years-long displacement. Others shared feelings of profound sadness, loneliness, never-ending worrying, and longing to return to their homes on the reserves. Some were diagnosed with depression since the flooding and displacement, which was perceived to have been a direct result of living in hotels or in temporary housing after being evacuated for such a prolonged period of time.

Purposeful flooding, evacuation, and prolonged displacement also had serious physical health effects on many Elders with some sharing experiences of their health deteriorating. Elders shared that they acquired new chronic illnesses or experienced worsening illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension.

Some Elders identified a strong link between human health and the ecosystem. They acknowledged that the flood had a severe impact on the land, resulting in detrimental effects on food supply such as fish and game. Elders discussed mourning the lack of access to trapping and hunting, and shared experiences of not being accustomed to new food options in their urban environments, specifically the lack of affordable and accessible healthy choices.

‘It’s Been A Long Journey’

Many First Nations community members had no choice but to leave everything including their homes, with some situated in hotels in Winnipeg while others were assigned to hotels located in towns in the Interlake region. Due to the prolonged length of the displacement (eight years to date), many eventually moved to Winnipeg. Some Elders discussed how chaotic the move to the city was, with several Elders having to relocate more than 10 times until they were settled in rental housing.

Without stability and security in their lives, Elders shared feelings of never-ending stress living in the city, which was an unfamiliar environment. As a result of the high levels of stress, many evacuees experienced negative health and social outcomes, including marital break-ups, family disruption, miscarriages, depression, loneliness, substance abuse, and suicide. Some Elders witnessed premature deaths of many loved ones.

The emergency evacuation created a geographical separation for many families with many evacuees facing difficulties when adjusting to life in urban areas; some even experiencing culture shock and racism, with limited resources and support. For many evacuees, accessing basic services such as education options for children and housing was difficult. Some Elders indicated that there was a lack of support services to assist evacuees to facilitate the process of adjusting to an urban setting.

Concerns were also raised about children being exposed to racism, offensive attitudes, beliefs, values, and practices that Elders perceived to be inherent in an urban setting. Conversely, others shared that some children were adjusting well to living in urban areas, and feared they would experience culture shock when they eventually returned to the reserve. Some Elders discussed the need for youth recognition and stated that youths needed to feel more supported by the communities – in particular, from community leaders.

‘We Lost Our Possessions – The Flood Destroyed Everything’

Elders expressed grief in the loss of their homes and possessions, noting that fair compensation has not been actualized. However, the most profound loss was the flood’s negative impacts on the land and livelihoods. An Elder shared what she observed following the flood:

I saw animals floating on ice in the river going downstream. It’s very hard to talk about what they’ve been through. They won’t have no eggs. There are hardly any birds today, like ducks… . We used to see moose going across the river and deer used to go across the river.

The flood also damaged recreational areas on the reserves such as beaches and baseball diamonds. The landscape was destroyed, giving rise to invasive plant species, increasing water pooling, and recurring flooding.

Elders’ Definition of Minoayawin

Elders defined minoayawin in terms of a holistic state that integrated spiritual, physical, mental, and emotional well-being. From participating Elders’ perspectives, this term meant good spirit, good life, and good health. In relation to the human-made flood and forced displacement, many indicated that minoayawin included sleeping well, a mind clear of worries, and feelings of satisfaction where a person is situated (referring to one’s home, residence, and community). Other aspects included job security, happiness, what a person eats with an emphasis on gardening, and wild food, exercise, and freedom to practice one’s beliefs.

Elders identified different things they needed to do for their minoayawin and what they needed for healing. For well-being, a clean and safe environment was required. The need for a land base was a priority and expressed with a passion. Access to and living on the land was strongly linked to the First Nations’ minoayawin. The Elders strongly voiced that minoayawin was linked to the environment, clean water, clean air, living off the land, access to traditional foods, being on the land, living in harmony with nature, and a positive relationship with people, animals, and all living things.

Elders advised displaced First Nation community members to talk and share feelings and experiences of the evacuation and displacement. They encouraged community members to seek counselling and help. They recognized that the evacuation was, and is, a difficult, forced way of life, and may require a similar healing process as that needed to survive residential schools (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). It was also important to address physical health issues affecting the evacuees that have arisen since they were forced to evacuate.

Reconciling with Minoaywin

The overarching theme for the 2-day gathering of interviews and recordings was “reconciling with minoaywin” with five subthemes: (a) forgiveness, (b) social and community action, (c) unity, (d) self-determination, and (e) reclaiming identity and reconnecting with the land. Subthemes will be explained in detail.

Forgiveness

Elders discussed ways in which they learned and found space to forgive for what happened to their community, family, and themselves. The church was identified as a place that community members could access for healing and for learning how to forgive. Others discussed how it will take time to come to a place of forgiveness, but discussed that forgiveness will grow out of the healing process, and if one can forgive, and then the healing will come.

Social and Community Action

The second subtheme was social and community action. Many Elders identified this as an important way to move forward. Some participants discussed the importance of the church in the community, a place where people can meet, feel supported, share and talk about what has happened. Some Elders discussed the connection between healing and community support that is founded in the church.

In addition, many Elders discussed the need to go home – to go back to the community. Many discussed how this re-connection would bring a sense of happiness to many community members. Moving back to the community would bring a sense of stability. Some Elders shared how this action would reunite families that were separated by the flood and forced displacement.

Relying on friends and family was highlighted as a way to heal and move forward to a healthy place. Being active in the lives of children, friends, and family was important and it was a key component in restoring and rebuilding the community.

Having gatherings to bring everyone together was identified as helpful. Elders discussed the importance of socializing, keeping busy with travel, visiting, and sharing meals.

Unity

The third subtheme was unity, in that community members were standing together for change and support. Elders discussed how important it was for all members to stand united as one group against oppression and injustice. Many highlighted that if they stood together, they would be able to hold the government accountable for their actions and begin the healing journey. If flooded First Nation communities stood together, they could support each other more effectively, become more independent, take a stance, and move forward in their own way.

Many Elders pointed to the need to establish more effective relationships with the government. By standing together as a united front, lobbying for financial compensation for the multiple losses was crucial. Many Elders discussed the importance of community members receiving financial compensation for the loss of their land, property, and belongings. They noted that although financial resources would not erase the pain and suffering, financial resources were acknowledged nonetheless as an important step in the healing process.

Hearing the government acknowledge that the flood was a human-made disaster was also stressed as a way towards forgiveness and healing. Many Elders indicated that in order to forgive the provincial government for the 2011 flood and the forced displacement of many of their community members, an official apology was needed. Formal recognition would assist many in allowing the government to understand that their actions were wrong and detrimental to the long-term well-being of the people within these communities as well as to the integrity of the land and water systems.

Elders expressed that by standing in unity, First Nation Elders should be involved in advising the government on water and land use because they grew up in these regions and they know the land and water. Many Elders discussed strategy and policy development as important elements of ensuring that this type of emergency does not happen again. Creating a First Nations-specific emergency response plan and developing a communication strategy were two action items discussed at length. Elders suggested a resource handbook to help evacuees adjust to their “new” urban environment in the event of another evacuation with resources to access housing, education, employment, and health services.

Self-determination

The fourth subtheme was self-determination. Many Elders expressed that in order to move forward, the community would have to rebuild and move home on their own terms. Furthermore, several Elders discussed the divide between some community members. In order for there to be peace and forgiveness within, there was a need for mediation services to assist in conflict resolution. Some Elders acknowledged that in order to move forward, it would be vital for Elders to sit down with the entire community to discuss the concerns of the evacuees and to establish a collective way forward.

Reclaim Identity and Connection with the Land

The fifth subtheme was to reclaim identity and a connection to the land. Elders shared insights about community members needing to take a holistic approach to healing, forgiveness, and moving forward. This holistic approach would need to be further defined and understood by the community itself. However, the Elders highlighted the importance of reclaiming identity by returning home, restoring and reconnecting with the land and the water. The opportunity to teach the children the skills to live off the land, and engage in wilderness camping and nature retreats was another element that was brought forward when discussing healing.

Elders expressed a strong connection between healing and the land, spiritual well-being, a sense of community, mental health, physical health, and support. Well-being meant having a clean and safe environment including access to clean water and air, living off the land, access to traditional foods, being on the land, living in harmony with nature, and engaging in positive relationships with everything including people, animals, and all living things. Elders shared that these elements are crucial for the community to move forward in a peaceful way. These elements should also be heard by provincial government officials and First Nations leaders, and be represented in the actions from the provincial government and leadership within the First Nations community when moving forward.

Other important elements of healing included returning to traditional roots and finding their identity again, learning to forgive, saying prayers, and having faith and spiritual healing. All of these connected to the greater idea of moving forward and healing.

Discussion and Conclusion

Based upon the study’s findings, the authors designed a healing booklet as well as a website to share the Elders’ insights about their peoples’ and communities’ need to heal with strategies to move forward in a holistic manner. Booklets (Hearing the Elders’ Voices – Minoaywin: A Healing Guide to Help the First Nations Communities Affected by the 2011 Flood to Begin Healing) were provided to members of the flooded First Nation communities via the IRTC. The booklet is also available on the website at https://manitobafloodhealingvoices.com/.

Documenting via the website at https://manitobafloodhealingvoices.com/ (and YouTube) has been invaluable as community members – both young and old; other Indigenous groups – including Métis and Inuit, non-Indigenous people, as well as those from different parts of the world can listen to their stories, and learn the resilience of the people who were displaced and learn how to reconcile with healing. The Indigenous people – including the Métis and Inuit, who are often the unwarranted recipients of displacement – may benefit and heal from what the Elders share. It a place to share knowledge and oral history in the years to come.

One limitation of this study was the low number of participating communities. Because this was a project initiated and funded by IRTC, the flooded communities were limited to IRTC. A number of other First Nations communities were flooded out in 2011 and were outside the IRTC catchment area. Despite the limitation, one IRTC community (Lake St. Martin First Nation) was 100 per cent displaced by the 2011 human-made flood. The IRTC First Nations that were flooded out represent approximately 85 per cent of all First Nations that were flooded.

Another challenge was the large number of attendees at the gathering. Although manageable, some people did not have the opportunity to voice their concerns. Lastly, an overarching limitation was the sensitivity of the issue. There were still strong evocations of hurt, stress, anger, frustration, and loneliness that many of the participants chose not to talk about openly; others did not accept the invitation to participate in an interview.

Despite these limitations, this project provided a unique opportunity to share the valuable insights from these First Nation communities; to hear and listen to the Elders’ voices, as well as their key recommendations for moving forward and healing. Listening to the voices of the Elders on healing was important because of the position they hold in their communities. As stated by Edge and McCallum (Reference Edge and McCallum2006), Elders often hold a critical position, offering knowledge, guidance, and support. Therefore, the knowledge shared from the Elders on healing is an important step forward for the community and provides a path to follow for reconciliation.

The term minoaywin was central to the findings. Briefly, the term minoaywin can be understood as “the good spirit, and good health”. The overarching theme was identified as “reconciling with minoayawin”. Incorporating and respecting the Elders’ language and terminology was a key component in collection, analysis, and dissemination of the findings. Elders provided key recommendations to achieve minoayawin (well-being) including the need for forgiveness, for social and community action, for unity, for self-determination, and for reclaiming identity and reconnecting with the land.

Findings of this study supported the previous work of Collings (Reference Collings2001), Edge and McCallum (Reference Edge and McCallum2006), and Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Rosenberg, Abonyi and Lovelace2010) in respecting the Elders’ wisdom. Specifically, Collings (Reference Collings2001) noted the important role Elders have in communities, and different perspectives of aging portrayed through transmitting knowledge. In Wilson’s (Reference Wilson, Rosenberg, Abonyi and Lovelace2010) work, this study further supported the need for listening and understanding the health of Elders in communities, especially around identity and healing. This study’s findings also supported the work of Edge and McCallum (Reference Edge and McCallum2006) around the importance of culture, tradition, and spirituality.

The qualitative approach within a participatory framework and the video method may be used in other projects eliciting Elders’ guidance in healing from forced displacement. Participants at the Elders gathering appreciated the opportunity to share solutions on how to heal from the 2011 human-made flood. The Elders’ stories were powerful. The qualitative approach using a video provided an appropriate venue showing full emotion. Elders are the first to encourage people to talk. Since time immemorial of oral history and oral tradition, oral transmission is a form of healing. Further distribution of the Elders’ stories via website and YouTube provided accessibility for the target communities and beyond.

In this study, the Elders’ perspectives of maziaya were congruent with King, Smith, and Gracey’s claim that Indigenous peoples have a deep spiritual connection to the land and that loss of land is akin to a physical assault (Reference King, Smith and Gracey2009). Our findings supported Wilson et al.’s work (2011) in that older Aboriginal peoples’ health continues to be negatively impacted by colonial policies including land dispossession.

Further research is required to examine the effectiveness of the healing booklet and website in disseminating the Elders’ advice in reconciling with minoaywin. A longitudinal study is warranted to examine the multigenerational health impacts of the 2011 human-made flood and forced displacement, building upon Walls and Whitbeck’s work (2012). It would be beneficial to track the uptake of the Elders’ advice within these First Nation communities and link it to social and health outcomes.