INTRODUCTION

Background

Appendicitis is the most common cause of an acute abdomen.Reference Davies, Dasbach and Teutsch 1 However, the diagnosis can be challenging because a missed appendicitis represents the third largest number of malpractice claims for emergency physicians.Reference Brown, McCarthy and Kelen 2

Computed tomography (CT) scans have a sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing appendicitis of 99% and 95%, respectively.Reference Eko, Ryb and Drager 3 However, an adult’s approximate effective radiation dose for a CT abdomen and pelvis ranges from 11 mSv to 20 mSv, which is comparable to a natural background radiation of 3 to 5 years.Reference Wilson, Connolly and Lahham 4 Although ultrasound is a radiation-free option, many emergency departments (EDs) have limited hours when it comes to ultrasound availability. Moreover, when compared to point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), a radiologist-performed ultrasound has been shown to result in a 120-minute longer ED length of stay.Reference Rhea, Halpern and Ptak 5

Importance

Delays in the diagnosis of appendicitis are associated with increased morbidity and further progression of the disease process.Reference Smith-Bindman, Lipson and Marcus 6 Particularly, delays greater than 18 hours from ED presentation to appendectomy are associated with an increased length of stay and higher costs to the healthcare system.Reference Smith-Bindman, Lipson and Marcus 6

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to determine the test characteristics of POCUS use in the ED to diagnose appendicitis. The results of this study have the potential to facilitate earlier collaboration with our General Surgical colleagues in seeking definitive care for these patients resulting in decrease patient morbidity, length of stay in the ED, and the need for additional imaging.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a health records review of all POCUS studies for appendicitis. All studies for appendicitis and right lower quadrant pain were identified on Q-Path, the online database for POCUS scans done at an academic Canadian ED from December 1, 2011 to December 4, 2015.Reference Mallin, Craven and Ockerse 7 All scans were performed by physicians with Registered Diagnostic Medical Sonographer credentials or resident physicians completing POCUS fellowship training.

Study population

All patients greater than the age of 17 years who had an ultrasound to investigate right lower quadrant pain were included in the study. All educational scans and POCUS scans completed after radiologist-performed imaging results were obtained were excluded from the study.

Data collection

A previously published framework for completing medical record review studies was followed. 8 Abstractors were emergency medicine residents who were trained by abstracting data from practice medical records and were blinded to the hypothesis. The results were compared to a gold standard of pathology, if available. If pathology was not available, the gold standard was considered to be laparoscopy, CT scans, and radiologist-performed ultrasounds, respectively. The gold-standard results were abstracted independently of the POCUS results.

For the purposes of this study, POCUS was considered positive if the appendix was visualized, non-compressible with an external diameter of more than 6 mm. Indeterminate scans or scans where the appendix was not visualized were considered to be negative in accordance with literature showing high negative predictive values of non-diagnostic and indeterminate ultrasound imaging for appendicitis.Reference Worster and Haines 9 However, patients who were POCUS-indeterminate with a high suspicion of appendicitis were imaged by Radiology.

Outcome measures and analysis

The primary outcome was the rate of correctly diagnosed appendicitis through POCUS. The specificity, sensitivity, and likelihood ratios of POCUS to diagnose appendicitis were calculated. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated using the Wilson score.

Ethical issues

This study was subject to an ethics review and was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board prior to a data abstraction commencement.

RESULTS

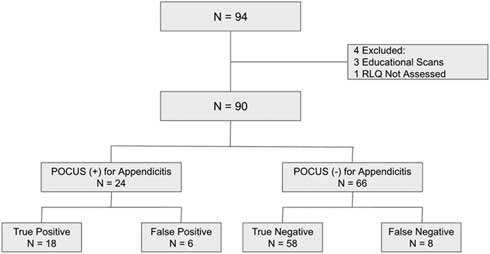

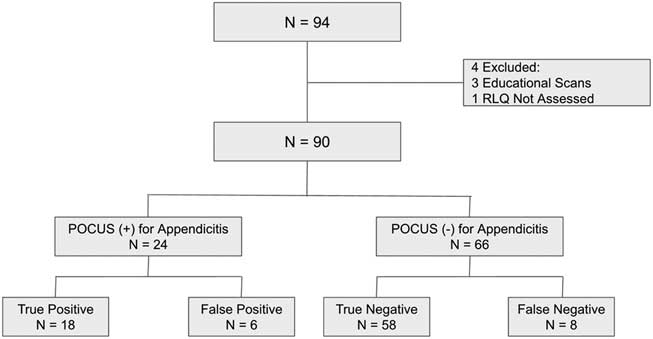

There were 94 patients included in the study. Four were excluded because 3 of the patients had educational ultrasounds performed on them, and 1 did not have the right lower quadrant assessed (Figure 1). Twenty-four patients had positive POCUS findings for appendicitis, and 66 patients had a negative and/or indeterminate findings for appendicitis (see Supplementary Table 1). There were 6 patients with false-positives in this study (see Supplementary Table 2) and 8 patients with false-negatives (see Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1 Study flowchart. POCUS = point-of-care ultrasound; N = number; RLQ = Right-Lower-Quadrant.

Primary results

The sensitivity and specificity for POCUS to diagnose appendicitis was found to be 69.2% (95% CI, 48.1%-84.9%) and 90.6% (95% CI, 80.0%-96.1%), respectively (see Supplementary Table 4). In addition, Cohen’s kappa statistic was determined to be 1.0. The positive likelihood ratio for POCUS to diagnose appendicitis was found to be 7.4 (95% CI, 3.3-16.5), and the negative likelihood ratio was found to be 0.3 (95% CI, 0.2-0.6).

DISCUSSION

These results are comparable to current literature on POCUS for appendicitis, as shown in a study by Mallin et al. in 2015. This prospective study of 97 adult cases yielded a sensitivity of 67.65% (95% CI, 49.5%-82.6%) and a specificity of 98.41% (95% CI, 91.4%-99.7%) of diagnosing appendicitis with bedside ultrasound.Reference Cohen, Bowling and Midulla 10 If all patients who were POCUS-positive for appendicitis went to the operating room directly, it would result in a 26.7% reduction in diagnostic imaging utilization.

This study’s strengths include a robust review of the medical records with trained abstractors using specific data abstraction forms. Of critical importance, the Cohen’s kappa statistic was found to be 1.0, and all scans were subject to a rigorous quality-assurance process.

LIMITATIONS

One of the limitations of this study is the lack of consecutive patient enrolment because not all patients suspected of appendicitis had an ultrasound performed by emergency physicians (i.e., patients with low pretest probability may not have had POCUS). This limited our data set and could have potentially confounded our results through selection bias. Moreover, this study is also limited because of the small number of patients included leading to wide CIs. This contributed to the positive and negative likelihood ratios to not reach significant values. However, using a pretest probability in combination with POCUS findings and other tests will still be of benefit. Further steps that could be taken to improve this study would be to perform a prospective study with a larger patient population.

CONCLUSIONS

POCUS is a reliable imaging modality for ruling in acute appendicitis. In cases where POCUS is negative or indeterminate for appendicitis, further imaging should be obtained as clinical suspicion warrants. Given the high specificity and positive likelihood ratio, the use of POCUS with a high pretest probability can hasten the process of achieving definitive management through earlier surgical consultation. This has the potential to decrease patient morbidity, length of stay in the ED, and the need for additional imaging.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank McMaster University and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton for their work in this study.

Competing interests: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no disclosures to make.

Supplementary materials

To view Supplementary Material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.373