Going over: the next steps?

Long archaeological debate about the process of Neolithisation across Europe, going back to the nineteenth century, seems now finally to have been settled. Whether migrants were responsible for the introduction into Europe of a new way of life involving agriculture and a more settled existence, or whether this transition was in the hands of indigenous European hunter-gatherers themselves, using knowledge of new techniques and practices diffused from centres of innovation in the Near East, had been the big questions. Ancient DNA (aDNA) studies (Reich Reference Reich2018; and other references below), supported by earlier isotopic investigations (for example Price et al. Reference Price, Bentley, Lüning, Gronenborn and Wahl2001; Schulting & Richards Reference Schulting and Richards2002), appear at last to have sorted the major outlines of processes of Neolithisation. Virtually everywhere across Europe, including in regions where there were very respectable archaeological arguments in favour of a significant involvement for indigenous people if not indeed a leading role (eg Allentoft et al. Reference Allentoft and Willerslev2024), it now seems that incomers ultimately of Near Eastern genetic ancestry were principally responsible for the introduction of the new way of life.

That said, my aim in this paper is to argue that there is still considerable scope for further and better integration of archaeological and archaeogenetic results and for the continuing interrogation of the fine detail, region by region, of the revised and emerging big picture described above. I suggest that this may reveal much about the nature of migration and the varying conditions of the initial establishment of Neolithic settlement across Europe. It may also inform us on the possible contribution to change of indigenous people, though that is not my principal focus here.

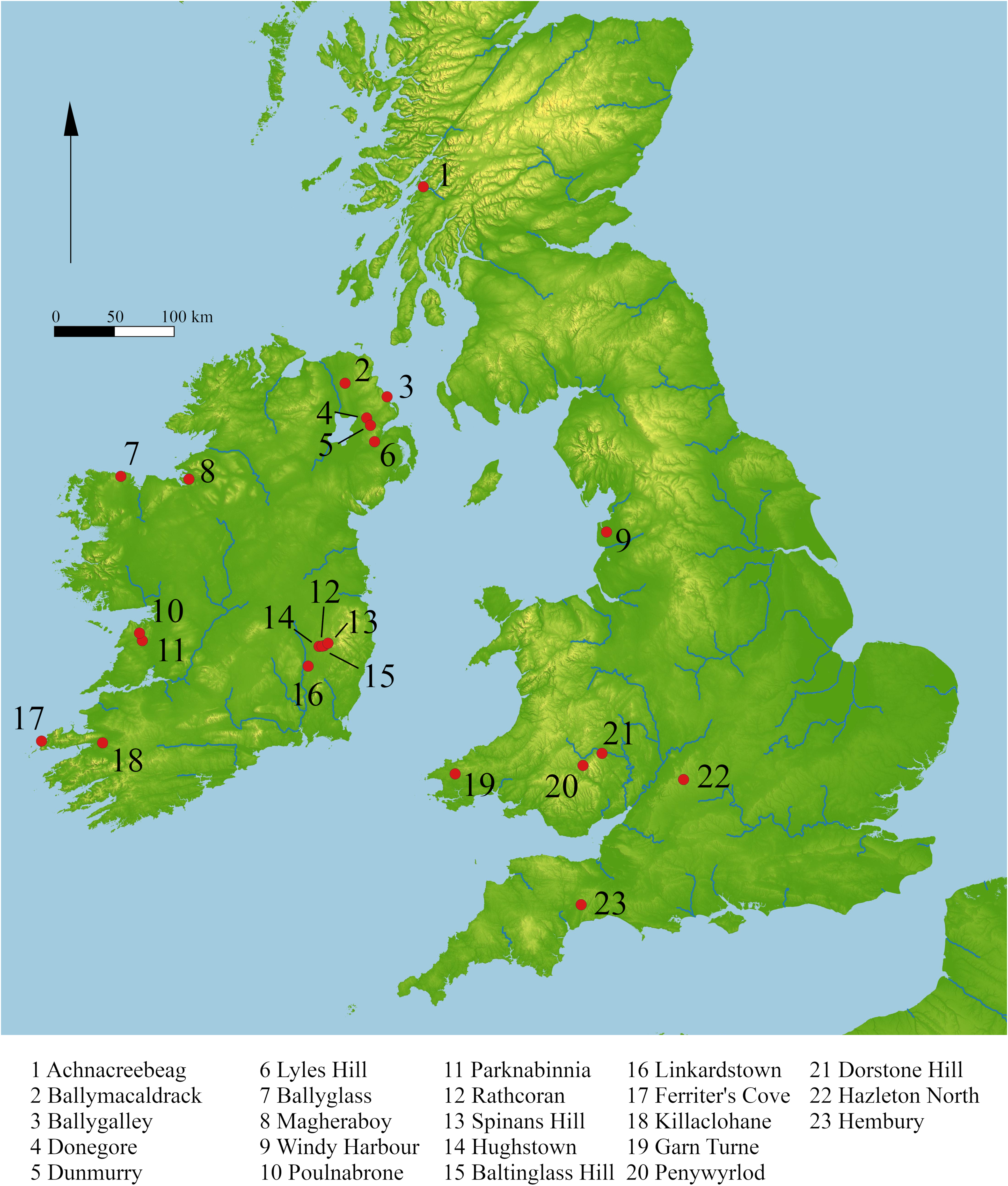

I concentrate here on relations between Britain and Ireland in the early Neolithic (Figure 1). I argue that for varying reasons the specific relationship between Britain and Ireland at the start of the Neolithic has tended to be overlooked — hidden in plain sight — in wider searches for continental origins and broader processes, and that more remains to be done to interpret the evident connections between the two islands once Neolithic lifeways had been established in both. With advances in chronological resolution and scientific analysis, not least of aDNA, we are in a stronger position to attempt more ambitious historical approaches to early Neolithic connectivity across the Irish Sea. I deliberately offer a generalised characterisation of the vast literature, and from that develop three propositions about the nature and trajectory of change. That takes us into the realm of early Neolithic politics, using that term as a summary of differing aspects of social relations; useful definitions are to be found in Paul Sillitoe (Reference Sillitoe2010, 13: ‘when we go beyond accounts of technology or subsistence activities to how these relate to the wider social order, we invariably find ourselves considering political matters too’), and in Daniela Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024, 23: ‘the term politics refers to negotiating between different, possibly diverging, conflicting or mutually opposed interests, values and worldviews of individuals or groups, and to how decisions are made and executed’). That leads to a fourth proposition, about the conditions in which close relations between Britain and Ireland developed and were maintained. Overall, in selectively covering themes of the circumstances of pioneering Neolithic settlement, the nature of the first Neolithic activity including here principally monuments or constructions, and political and social dimensions of early Neolithic connectivity, roughly from the 41st to the 37th and 36th centuries cal BC (Table 1), and with a recurrent interest in matters of scale, I hope to explore questions of parallel interest for many other regions beyond Britain and Ireland (see eg Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024).

Fig. 1. Specific sites mentioned or discussed in the text.

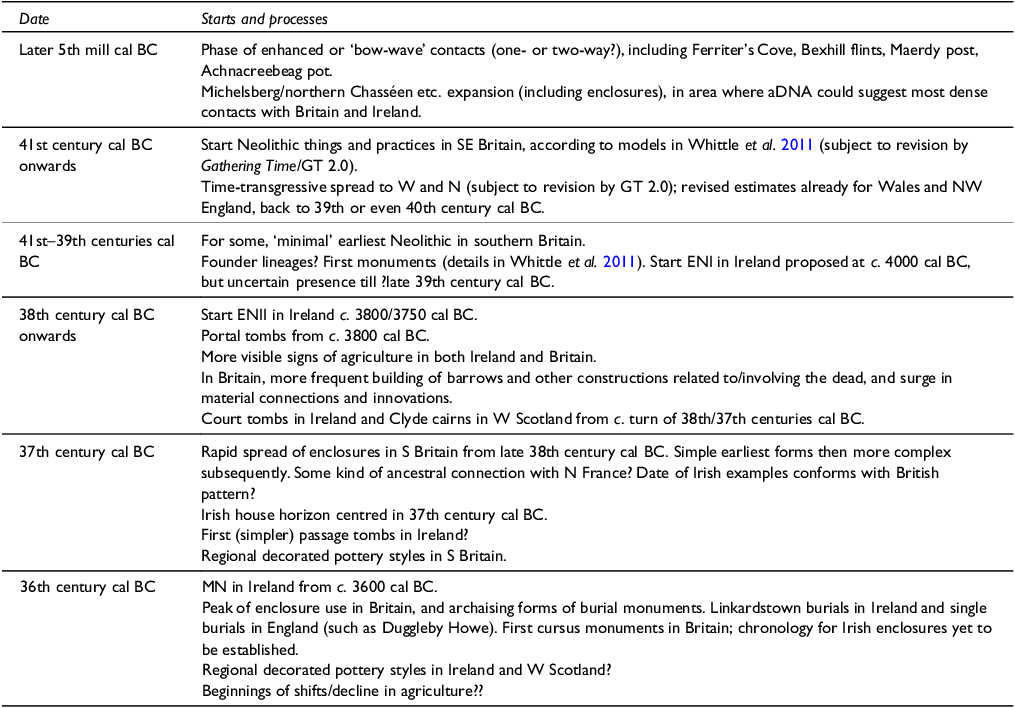

Table 1. Summary of some of the key elements of a possible chronology for selected aspects of the early Neolithic in Britain and Ireland, subject to ongoing and future modelling

Under-interpreted connections between Britain and Ireland

An old debate resolved, at one scale?

There is by now a vast literature on the themes of the Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland from the European continent, the monuments and material culture of the early Neolithic of these offshore islands, and the western seaways (out of much longer lists, see Cooney Reference Cooney2000; Callaghan and Scarre Reference Callaghan and Scarre2009; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2010; Anderson-Whymark & Garrow Reference Anderson-Whymark and Garrow2015; Cummings Reference Cummings2017; Bradley Reference Bradley2019; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020; Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Hofmann, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2022; Cooney Reference Cooney2023; Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024). It is also worth remembering debate about the extent to which the Irish Mesolithic was connected to the wider world (O’Kelly Reference O’Kelly1989; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004; Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007; Reference Sheridan2010; Woodman Reference Woodman2015; Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy and Bradley2020; Warren Reference Warren2022); I have discussed elsewhere the range of possible ‘bow-wave’ contacts between the Continent and Britain and Ireland in the later fifth millennium cal BC (Whittle Reference Whittle2024a; Reference Whittle2025).

At one scale, thanks above all to aDNA analysis as noted above, the long debate about the nature of the Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland is now seemingly resolved as part of the big story about the migration of people of ultimately Near Eastern ancestry and the appearance of such incomers in almost every part of Europe (Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy, Martiniano, Murphy, Teasdale, Mallory, Hartwell and Bradley2016; Reich Reference Reich2018; Brace et al. Reference Brace and Barnes2019; Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy and Bradley2020; Rivollat et al. Reference Rivollat and Haak2020; Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025). It is also hard to think of any category of early Neolithic material culture, monumentality and settlement on either side of the Irish Sea that has not been thoroughly discussed (see, among many others, Cooney Reference Cooney2000; Cummings Reference Cummings2017; Bradley Reference Bradley2019; Cooney Reference Cooney2023).

These investigations are framed by increasingly robust and precise chronological narratives (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Murphy, Jones and Warren2012; McClatchie & Potito Reference McClatchie and Potito2020; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020; Griffiths Reference Griffiths2021). It is important, however, to acknowledge remaining questions about the detail of the sequences in both Britain and Ireland. There are still rival models for process and timing (Table 1), for example from the multi-strand scenarios of Alison Sheridan to the kind of spread proposed in Gathering Time (eg Sheridan Reference Sheridan2010; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011; Ray & Thomas Reference Ray and Thomas2018; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020; Sheridan & Whittle Reference Sheridan and Whittle2023). Julian Thomas (Reference Thomas2022) has proposed a minimal set of activities in the earliest Neolithic in Britain, later reinforced by continuing migration streams from the Continent, the consolidation of settlement and the establishment of a full agricultural economy (cf. Griffiths Reference Griffiths2018); that remains to be worked out in detail, as there are signs that Neolithic activity including clearance and cereal cultivation could go back to the 40th century cal BC in parts of western Britain (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2021; Whittle Reference Whittle2024a; Reference Whittle2025). Remodelling of Gathering Time for England and Wales is planned, with hundreds of new radiocarbon dates collected (with Alex Bayliss and Frances Healy). Likewise, there remains plenty of uncertainty about the detailed chronology of the early stages of the Neolithic sequence in Ireland. Succeeding the complicated models mooted in Gathering Time (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapter 12), an ENI from c. 4000–3800/3750 cal BC is now proposed before an ENII, from c. 3800/3750–3600 cal BC (Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Schulting, McClatchie, Barratt, McLaughlin, Bogaard, Colledge, Marchant, Gaffrey and Bunting2014; McClatchie & Potito Reference McClatchie and Potito2020; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020; Cooney Reference Cooney2023). By ENII, there is abundant evidence for settlement including the striking house horizon, clearance and cereal cultivation, and a range of monuments including portal tombs, court tombs and probably the first passage tombs, but activity in ENI is much harder to define and pin down reliably (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, McClatchie, Sheridan, McLaughlin, Barratt and Whitehouse2017; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020).

Despite such uncertainty, the resulting big picture for the offshore islands confirms the older, traditional view of incoming migrants, as expressed for example in the claim made over 60 years ago that ‘at some time there must have been an immigration of Neolithic farmers […] into Ireland’ (Corcoran Reference Corcoran1960, 124). People came into Britain and Ireland probably from northern France, and possibly in two or more strands, one westerly, one eastern; there seems to have been relatively little contribution from indigenous people to early Neolithic genetic signatures except in western Scotland (Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy, Martiniano, Murphy, Teasdale, Mallory, Hartwell and Bradley2016; Brace et al. Reference Brace and Barnes2019; Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy and Bradley2020; Rivollat et al. Reference Rivollat and Haak2020; Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Sheridan & Whittle Reference Sheridan and Whittle2023; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025; note reservations in Thomas Reference Thomas2022). It is probable that these new arrivals considerably outnumbered the local populations (Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025), though we do not need to deny the latter all sense of agency and involvement in processes of change, and I have argued elsewhere that indigenous knowledge of landscape and its resources may have been of an importance out of proportion to contribution to genetic signatures (Whittle Reference Whittle2024a, 6; Reference Whittle2025, 117; cf. Cooney Reference Cooney2023, 108). The most detailed and extensive formal chronological modelling so far proposed a ‘time-transgressive’ process, beginning in south-east England in the 41st century cal BC, with progressive spread westwards and northwards (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011; subsequent models are noted below). Overall, for both Britain and Ireland, it seems to me appropriate to envisage a comprehensive Neolithic takeover by colonisation, even if we should be careful not to import all manner of modern, negative connotations of that term (cf. Crellin Reference Crellin2020, 10–12; Gori & Abar Reference Gori, Abar, Fernández-Götz, Nimura, Stockhammer and Cartwright2023).

The range of specific connections: growing possibilities

Moving to a tighter scale than that of the overall big picture for the offshore islands within the context of changes in north-west Europe, close connections in the early Neolithic between Britain and Ireland have long been recognised. That goes at least as far back as the generation of Stuart Piggott, whose masterly synthesis (1954) included the concept of the Clyde-Carlingford culture, based on the evident similarities between Clyde cairns in western Scotland and court tombs principally in the northern portion of Ireland (cf. Corcoran Reference Corcoran1960; de Valera Reference de Valera1960; and see below).

The list of probable and possible connections and similarities on either side of the Irish Sea, however, is now much longer (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 224–7; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004, 13; Cooney Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007, 549). It includes, variously: portal tombs (Kytmannow Reference Kytmannow2008; Mercer Reference Mercer2015; Cummings & Richards Reference Cummings and Richards2021); other cairns including court tombs and Clyde cairns (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Murphy, Jones and Warren2012; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020); non-megalithic mortuary structures (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995, 5; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 225); enclosures (Cooney Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007, 549; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011; Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024; O’Driscoll Reference O’Driscoll2024); pottery including carinated bowl (formerly labelled as Western Neolithic and Neolithic A) and some of the repertoire of decorated bowls found in both western Scotland and Ireland (Case Reference Case1961; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995); lithics including flint leaf-shaped and lozenge arrowheads (Case Reference Case1963, 6), Arran pitchstone and Antrim flint (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 225); and porcellanite axes from north-east Ireland found in Scotland and England, and Group VI and other axes found in Ireland (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 188, 204, fig. 6.16). To this can also be added cave burials on either side of the Irish Sea (Dowd Reference Dowd2015; Peterson Reference Peterson2019; Schulting Reference Schulting2020; Cooney Reference Cooney2023). In later phases, beyond the principal focus of this paper, there are also potentially striking similarities in the distribution of individualised burials in round barrows and cairns in parts of northern England and Ireland (eg Gibson & Bayliss Reference Gibson and Bayliss2009; Cooney Reference Cooney2023, for the Linkardstown type), and indeed of cursus monuments (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 165–6, 169; O’Driscoll Reference O’Driscoll2024; cf. Bradley Reference Bradley2024).

As already noted, recent aDNA analysis has had a key role in resetting the big picture. Common, shared origins in continental Europe for new population in both Britain and Ireland have been one recurrent focus of discussion, with northern France regularly proposed as the nearest and most likely source area (Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025; see also Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024, chapter 3). Further detail remains elusive, and the lack of samples from Brittany is still an obstacle to better understanding (Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023, 160); nonetheless aDNA samples from late Mesolithic contexts there give some ground for optimism about future investigations (Simões et al. Reference Simões and Jakobsson2024). But as well as helping to consolidate the big picture, aDNA analysis has also established an almost identical genetic signature for the early Neolithic populations of both Britain and Ireland. There are now indications of some direct if fairly distant genetic (perhaps family) connections across the Irish Sea revealed through identity-by-descent analysis and possible evidence for continuing intermarriage across the Irish Sea, in contrast to a seeming lack of comparable evidence across the English Channel (Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023, 137, 143). The suggestion has also been made of ‘patrilineal affiliations between high-status men that stretched back many generations in time’ (Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023, 160–1; see also Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025).

Two remaining gaps in coverage and interpretation of the nature of connectivity

All this represents considerable progress (with suitable caveats about enduring uncertainties). Yet, looking over the extensive literature, I see two very significant gaps in coverage and interpretation.

First, nearly all recent syntheses and discussions of the initial Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland tend to talk in rather general terms about derivation from probably common or shared areas of origin on the European continent, and to swerve around the sharper question of the relationship between Britain and Ireland in this process. That can be seen both in wider syntheses and discussions (eg Cummings Reference Cummings2017; Ray & Thomas Reference Ray and Thomas2018; Bradley Reference Bradley2019; Cooney Reference Cooney2000; Harris Reference Harris2021; Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Hofmann, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2022; Cooney Reference Cooney2023; Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024) and in the outputs of specific projects concerned with topics such as the western seaways (eg Callaghan & Scarre Reference Callaghan and Scarre2009; Garrow & Sturt Reference Garrow and Sturt2011; Anderson-Whymark & Garrow Reference Anderson-Whymark and Garrow2015; Garrow & Sturt Reference Garrow and Sturt2017; Garrow et al. Reference Garrow, Griffiths, Anderson-Whymark and Sturt2017) or particular kinds of monuments (eg Kytmannow Reference Kytmannow2008; Mercer Reference Mercer2015; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020). For example, although there is a long history of writing about the western seaways from the later nineteenth century into the 1930s, documented in detail by Richard Callaghan and Chris Scarre (Reference Callaghan and Scarre2009, with references), and supplemented by further considerations of currents and sea conditions (eg Davies Reference Davies1946; Case Reference Case1969a; Bowen Reference Bowen and Moore1970; McGrail Reference McGrail1997; Cooney Reference Cooney, Cummings and Fowler2004; Bradley 2019, 19–24; Reference Bradley2022; see also Bradley Reference Bradley2023), all of which discuss the challenges of sea travel and the possibilities of successful connection by and across water, the principal focus has nearly always been on the general link between the Continent and the offshore islands of Britain and Ireland. This can be seen in a summary figure from the excellent work on the western seaways by Hugo Anderson-Whymark and Duncan Garrow (Reference Anderson-Whymark and Garrow2015, fig. 5.5), who usefully ‘re-image’ continental connections between 5000 and 3500 cal BC. Up to six spheres of interaction are posited and mapped. Two (nos 2 and 3) include the Irish Sea respectively in part and as a whole, and a third (no. 6) impinges on its southernmost part, but there is no sphere directly addressing the central or northern parts of the Irish Sea itself. Gathering Time (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapters 12, 14 and 15) has addressed this more directly in recent times (though see also Garrow et al. Reference Garrow, Griffiths, Anderson-Whymark and Sturt2017), but even that tends only to hint at possibilities (such as mapped in Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, figs 14.177 and 15.8) and does not enter into extended or locally detailed discussion of the implications (see further below). To my knowledge, only Neil Carlin and Gabriel Cooney (Reference Carlin, Cooney, Card, Edmonds and Mitchell2020, 332) have explicitly recognised a contrast between continental and intra-insular contacts, writing (albeit briefly) that ‘past interactions between continental Europe and Ireland or Britain are often considered from a present-day perspective to be much more significant than insular contacts. This is especially the case if they involved the movement of people with slightly different genes, even if these involved much shorter journeys such as those across the English Channel to northern France’.

One has to go back to older treatments (eg Childe Reference Childe1946; Piggott Reference Piggott1954; Corcoran Reference Corcoran1960; Case 1963; Reference Case1969b; see also Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995; Cummings & Fowler Reference Cummings and Fowler2004) to find useful, detailed and sustained accounts (whatever other flaws there may have been in pre-processual, culture historical approaches) which actually address Irish Sea connectivity head-on. Setting the scene, and borrowing from Bronisław Malinowski, Gordon Childe (Reference Childe1946, 36; cf. Garrow & Sturt Reference Garrow and Sturt2011) evoked in a celebrated phrase ‘grey waters […] bright with Neolithic argonauts’ in discussing the western seaways of Britain. Stuart Piggott had earlier (Reference Piggott1934, 376) written about ‘complex infiltrations of small groups of people at various points along our coast’, and in his wider synthesis (Piggott Reference Piggott1954) envisaged the arrival into Ireland of early agricultural colonists using pottery of the ‘Western’ family tradition, including an early influx from north-east England, along with non-megalithic funerary architecture and Grimston-Lyles Hill pottery (now labelled as carinated bowl). He also proposed a later influx of court tomb builders coming from south-west Scotland and even imagined (Piggott Reference Piggott1954, 151) the people of his proposed Clyde-Carlingford culture as having set off originally from the Pyrenees. I have already noted the view of John Corcoran (Reference Corcoran1960, 124) that the origins of ‘Neolithic A’ pottery — the carinated bowl tradition — were to be found outside Ireland.

Humphrey Case, well-known for his wider essay on Neolithisation including the practicalities of sea travel, scouting, pioneering and initial establishment (1969a), also wrote in detail about connections between Britain and Ireland (1963; 1969b), having previously examined the Irish Neolithic pottery sequence (1961). He began with the assumption that ‘Western Neolithic’ pottery in Ireland was introduced ‘from overseas’ (Case Reference Case1961, 200), suggesting that it was commonsense to look for the origins of his Dunmurry style (now seen as part of the carinated bowl tradition: Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995) in Brittany (Case Reference Case1961, 222). By the time of his next paper, he saw the best parallels for that component in the Grimston ware of the Yorkshire Wolds, with the question of overall origins being left open (Case Reference Case1963, 4, 8); he also noted very similar leaf and lozenge arrowheads throughout Britain and Ireland. In his last paper on this theme, focused on the north of Ireland, his narrative had sharpened. While seeing ‘the whole of Atlantic Europe accessible from northern Ireland to those engaged in seasonal movements’ (Case Reference Case1969b, 7), he regarded the close lithic resemblances, particularly in arrowhead forms, as showing ‘close relatives in England’ (Case Reference Case1969b, 10) and concluded that the ‘earliest settlers in north Ireland are more likely to have come from or through the Wolds, than elsewhere in the British Isles or continent of Europe’ (Case Reference Case1969b, 11). In her useful refinement of Case’s pottery scheme for Ireland, Alison Sheridan developed things a little further, contrasting an early phase of carinated bowl pottery (cf. Herne Reference Herne1988) ‘of the same type as that seen over much of Britain’ (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995, 17) with a following phase of modification and diversification (1995, 6). Her treatment of carinated bowl pottery in her subsequent series of papers on strands of Neolithisation in Britain and Ireland (eg Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004; Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007; Reference Sheridan2010) strongly implies derivation from Britain, but she has not pursued those specific links in further detail and seems to explain similarity in material culture again by shared continental ancestry (Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004, 9). She did, however, note probable later connections with western Scotland (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995, 6; cf. Sheridan Reference Sheridan2016) and the possible resemblance of some pottery in the north of Ireland to the Hembury style of south-west England (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995, 17).

The second significant gap in the literature which I see is that, while syntheses and discussions have recognised the many possible connections between Britain and Ireland after initial Neolithisation (eg Corcoran Reference Corcoran1960, 134; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 225; Cummings & Fowler Reference Cummings and Fowler2004; Cooney Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007, 549), rather little has been done with interpretation of these beyond basic description and identification; much more could be done with the sociality and politics of connectivity (Figure 2). For example, Gabriel Cooney (Reference Cooney2000, 14) recognised ‘the strong links to ceremonial traditions in northern Britain’ of the wooden mortuary structure at Ballymacaldrack, Co. Antrim and ‘international styles of pottery, linking Britain and Ireland’ (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 184); he also refers to ‘hands across the sea’ in the material links between north-east Ireland and south-west Scotland, and ‘a sense of shared identity’ (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 224–5), and has suggested that inhabitants of places like Ballygalley in Co. Antrim ‘could have perceived themselves as embedded in a social context that stretched across the Irish Sea’ (Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 227; see also Cooney Reference Cooney, Cummings and Fowler2004); at the same time, he has cautioned against assuming a single identity in early Neolithic Ireland (Cooney Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007, 552). These are all highly valuable observations, but they are not developed into a wider account of Irish Sea connectivity. Recent aDNA papers come closest to broadening the discussion, with, as noted above, suggestions of similar origins and continuing intermarriage (Cassidy Reference Cassidy, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023, 153, 160–1; Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023, 137; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025), but even these are comparatively limited in discussing possible implications. None of the recent accounts I have so far cited appears to put either observations or consequences into a wider or more detailed narrative.

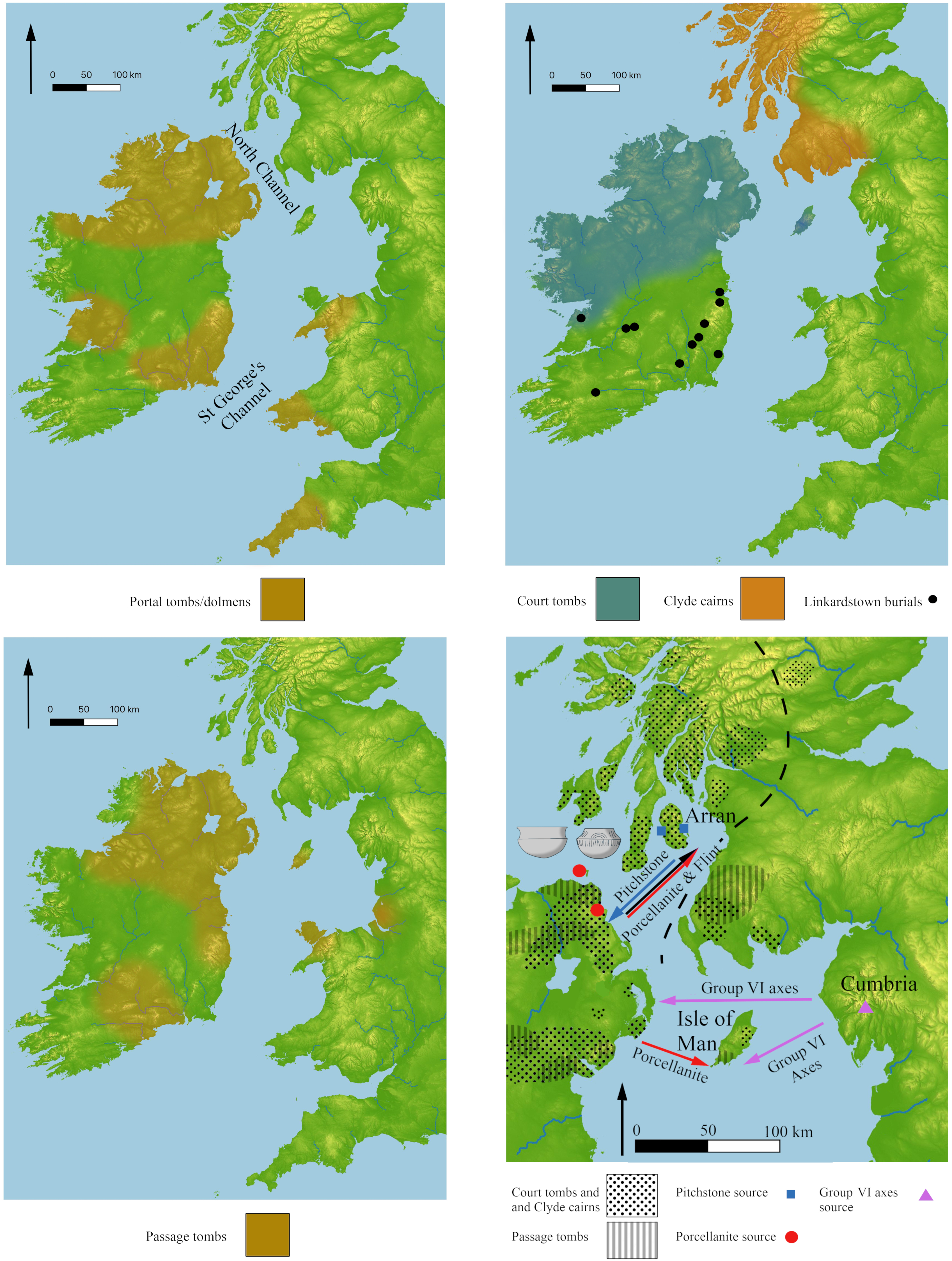

Fig. 2. Some of the connections and similarities in early Neolithic practices across the Irish Sea. Distributions to left, top right and bottom left principally after Cooney (2001; Reference Cooney2023) and Kytmannow (Reference Kytmannow2008). Bottom right redrawn after Cooney (Reference Cooney2000, fig. 7.3).

It is interesting to speculate why this has been and seems to continue to be the case. Perhaps there have been a number of factors at work. An older generation of scholars was more comfortable with specific, historical explanations, especially when it came to questions of origins (cf. Hodder Reference Hodder1987). And then there are all manner of modern (and not so modern) political sensitivities about relations between Britain and Ireland, from The Troubles right through to the current post-Brexit situation and issues to do with customs borders. In such a context, perhaps it is understandable that, consciously or unconsciously, researchers have avoided detailed issues of origins, derivation and connectivity (cf. Cooney Reference Cooney, Bender and Winer2001).

So in the rest of this deliberately speculative paper, I want to consider how the two gaps I have identified are to be closed in future research. Definitive models are not yet possible, with further chronological modelling to be done and more aDNA analysis to be carried out. I want to explore therefore what possible answers to come might look like. I advocate the need for a more detailed, contextual and historical approach than found in many recent accounts (as also argued by Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsen2024), and I will try to outline the potential contribution which more ambitious narratives of the politics and sociality of the connectivity between Britain and Ireland could make to our understanding of the early Neolithic on either side of the Irish Sea. I will also attempt to link the two claimed gaps, arguing that intense connectivity across the Irish Sea in the early Neolithic was rooted in the circumstances of the initial relationship between Britain and Ireland in the process of Neolithisation. I offer four propositions for debate.

Notes towards a narrative of Irish Sea connectivity in the early Neolithic

Beginnings

With all this in mind, my first proposition is that the bulk of initial Neolithic communities came to Ireland via Britain. This is based on chronological priority, reinforced by shared material culture, and now backed up by aDNA analyses.

While all chronological models can benefit from revision (Table 1 and discussion above), the most extensive previous estimates suggest that the earliest incoming Neolithic communities in Britain and Ireland were in the south-east of England, probably in the 41st century cal BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapter 14). Gathering Time envisaged a time-transgressive process of subsequent spread to the west and north, perhaps accelerated by the 39th century cal BC by fusion with indigenous people (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 862). Its models, based on the dates available at the time, indicated that the Neolithisation of south-west England, the Isle of Man, southern and north-east Scotland, and Ireland, occurred more or less at the same time in the later 39th century cal BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 862, figs 14.176–7). Its preferred model 3 for Ireland (for full details, see Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapters 12 and 14) suggested that the start of the Irish Neolithic fell in the later 39th–earlier 38th century cal BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 663, fig. 12.57). With more dates available, these models cannot be regarded as stable. Estimates for the start of Neolithic activity in north-west England, based on a series of occupation sites investigated and modelled since Gathering Time, now go back to the later 40th and earlier 39th centuries cal BC (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2021, 36, fig. 3.3); other sites since investigated, such as Windy Harbour, Lancashire (Fraser Brown, pers. comm.), will contribute importantly to the refinement of such estimates. Likewise, estimates for the start of Neolithic activity in south Wales and the Marches can be pushed back to the 39th century cal BC (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2022; cf. Ray et al. Reference Ray and Wiltshire2023), and further dates from sites in Cornwall are likely also to entail revision of start dates in this region (Jones & Quinnell Reference Jones and Quinnell2021; Whittle Reference Whittle2024a; Reference Whittle2025).

Meanwhile in Ireland, as already noted, there has emerged a division of the early Neolithic into an ENI, from c. 4000–3800/3750 cal BC, and an ENII, from c. 3800/3750–3600 cal BC (Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Schulting, McClatchie, Barratt, McLaughlin, Bogaard, Colledge, Marchant, Gaffrey and Bunting2014; McClatchie & Potito Reference McClatchie and Potito2020; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020), with one account noting an almost ‘invisible’ presence in ENI (Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020, 428, 432). Such a scheme is compatible with the preferred model 3 of Gathering Time, and can accommodate the now preferred chronological interpretation of deposition at Poulnabrone, Co. Clare, beginning around 3800 cal BC (Lynch Reference Lynch2014, and see below; Gathering Time had taken a different line on that monument) and probably early 38th-century activity at Baltinglass Hill, Co. Wicklow (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, McClatchie, Sheridan, McLaughlin, Barratt and Whitehouse2017; see also Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020, 432); another portal tomb at Killaclohane II, Co. Kerry, could belong to the 38th century cal BC based on finds and a single radiocarbon date (Connolly Reference Connolly2021). We must also set aside the allegedly early date for the Magheraboy enclosure in Co. Sligo of around 4000 cal BC, which had exercised us so much in Gathering Time, since recent remodelling with different assumptions about the age of wood samples suggests revised probabilities in line with those for other enclosures (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024, fig. 4). In the same way, it still seems wise to set aside the claims for an early, Atlantic or Breton strand up the west side of Britain and potentially involving Ireland (Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004; Reference Cooney, Whittle and Cummings2007; Reference Sheridan2010; Reference Sheridan2016; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020). If the Achnacreebeag pot, for example, is not to be seen as in a regional tradition of decorated pottery in western Scotland, it could still be accommodated as one of a series of ‘bow-wave’ contacts with the Continent (as noted above), including the episode at Ferriter’s Cove (Woodman Reference Woodman2015; Whittle Reference Whittle2024a; Reference Whittle2025), and I think it is telling that there is no similar material from the many recent road schemes in Ireland (Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin and Cooney2017; and references below).

Thus, we can formalise the proposition that the earliest Neolithic in Ireland was not only later than first activity in Britain, including in western Britain, but was also in the hands of people who principally came from Britain. That is to reinstate, in modified form, the arguments of Stuart Piggott and Humphrey Case as noted above, though without the need to invoke a specific route involving Yorkshire and north-east England. This seems to me to make sense of the long-agreed similarities in pottery and lithics alike and also of the close similarities in genetic signatures discussed above. Those are there in my view because this was essentially the same population on the move, engaged in probably multiple and regionalised migratory moves and the progressive intake of the whole of the offshore islands, in a process lasting probably, as far as the west of Britain and Ireland are concerned, from the 40th to the early 38th centuries cal BC.

Enduring and intensifying connections

The long list of plausible connections between Britain and Ireland subsequent to initial Neolithisation has often been described, but here the challenge is to take interpretation further. Thus my second overall proposition is that cumulatively these connections mark a phase of considerable and potentially intensifying interaction, stemming from the conditions of initial colonisation. This may have involved varying participants and diverse connections in several directions, in contrast to the implied east–west movement of migration.

Firstly, it is worth emphasising yet again the range of possible and plausible connections between Britain and Ireland in the early Neolithic: not a unified set by any means but more concentrated and coherent than the connections between the European continent and the offshore islands (Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Card, Edmonds and Mitchell2020, 332), which have proved notoriously hard to track over more than a century of research on the beginnings of the Neolithic. They seem to involve practically every dimension of early Neolithic existence, from daily life and settlement to aspects of monumentality, mortuary customs and other social practices.

Secondly, and more specifically, there seem to be many interwoven themes at play. The movement of materials and finished products of for example porcellanite, Lakeland tuff, Antrim flint and Arran pitchstone project a general picture of considerable mobility, perhaps largely through what Humphrey Case (Reference Case1969a) called ‘seasonal mobility’, some of it presumably representing gift and other exchanges, and some the stuff of daily life around and across the Irish Sea (Cooney Reference Cooney, Cummings and Fowler2004, 149). If individuals and small groups were regularly on the move between Britain and Ireland, they would presumably have found themselves in very familiar physical and social settings.

In this world, similar pottery and lithic styles could well have projected a common sense of origin and shared identity in daily life. Although the carinated bowl tradition was by no means unchanging (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995, 17; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, 757–9, 824–8), it seems to have persisted through the Irish house horizon (eg Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin and Cooney2017; Johnston & Kiely Reference Johnston and Kiely2019; Bayley & Delaney Reference Bayley and Delaney2020; Long Reference Long2020; Moore Reference Moore2021; Walsh Reference Walsh2021; Carlin Reference Carlin2024), and tellingly it is present in sites with houses in north-west Wales around 3700 cal BC (Kenney Reference Kenney2021). The time is surely ripe for a wider, fresh look at the carinated bowl tradition across Britain and Ireland (cf. Pioffet Reference Pioffet2017). A sense of common identity might also have been projected through the use of similar rectangular houses on either side of the Irish Sea. There is an argument that large halls as found in lowland Scotland began earlier than the main Irish house horizon (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapters 12 and 14). Not all Irish houses need be understood in the same way, and their significance for patterns of daily life on the one hand and for special social significance on the other (Cross Reference Cross, Armit, Murphy, Nelis and Simpson2003; Smyth Reference Smyth2014) may have varied, but some of the larger and more prominent ones at least may have signalled wider connections, real and perceived, to Britain and beyond. Similarities in mortuary structures, enclosures, cave burials and even axe production in remote places may also have fostered differing senses of shared origins and identity, alongside local attachments, allegiances and ways of doing things (cf. Cooney et al. Reference Cooney, O’Neill, Revell, Gilhooly and Knutson2024); I explore aspects of mortuary structures and enclosures further below.

What Gabriel Cooney (Reference Cooney2000, 224) called ‘hands across the sea’ could now also be sharpened further into patterns of intermarriage, as suggested by the aDNA interpretations noted above, and potentially diverse forms of kinship. Using Andrew Powell’s (Reference Powell2005) and Chris Fowler’s (Reference Fowler2022) arguments that mortuary architecture may often have presented differing kinds of kinship and connections with the past, the array of wooden and stone mortuary structures could in general suggest varying kinship and other social links on either side of the Irish Sea. There are also important and varied differences here. Wooden mortuary structures are scarce (though so far a little more numerous in Scotland than in Ireland) compared to other forms of construction. Portal tombs or dolmens offer the closest resemblances in form and possible function on either side of the Irish Sea, some typological variations notwithstanding (Kytmannow Reference Kytmannow2008, fig. 5.28; Mercer Reference Mercer2015; Cummings & Richards Reference Cummings and Richards2021); the distribution in Britain is strongly weighted to west Wales and south-west England (Kytmannow Reference Kytmannow2008, fig. 9.1). The Clyde cairn–court tomb linkage is by contrast oriented to the north-east of Ireland and the south-west of Scotland (Figure 2), and these architectural and mortuary traditions are closely similar but far from identical, though any participant in a funeral at one or other of these types of monument on either side of the Irish Sea would presumably have been familiar with the physical set-up: frontal area, receding or stacked chambers, and cairns. Portal tombs and court tombs within Ireland not only look different from one another but are placed differently in the landscape; and on this point we can learn much from earlier papers on these constructions (eg Davies Reference Davies1946; Corcoran Reference Corcoran1960; de Valera Reference de Valera1960; cf. Cooney Reference Cooney1979). Perhaps we can envisage social landscapes with local foci for particular lineages or other kin or social groupings (see Whittle Reference Whittle2024b) in the form of court tombs and Clyde cairns, signifying at one level one strand of origin focused on south-west Scotland and north-east Ireland, and other points of attention, in the form of portal tombs and dolmens, signalling another direction of connection and other concerns, following the arguments of Vicki Cummings and Colin Richards (Reference Cummings and Richards2021; see also Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Hofmann, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2022, 13) for dolmens as created places of awe and wonder in new landscapes; Garn Turne, Pembrokeshire, is a good example. Overall, there do not seem to be many hybrids bridging these two traditions, though there is some overlap (Kytmannow Reference Kytmannow2008, 60–9).

Enclosures offer another dimension and kind of potential connection. Previously, Magheraboy in Co. Sligo in the far west and Donegore in Co. Antrim in the north-east were the only known examples in Ireland (Danaher Reference Danaher2007; Mallory et al. Reference Mallory, Nelis and Hartwell2011; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapter 12). Now, upland surveys have shown the existence of other examples in eastern Ireland, including at Hughstown, Co. Kildare, and Spinans Hill 1 and Rathcoran, Co. Wicklow. These are hilltop enclosures, situated about 5 km apart in the Baltinglass area on the western side of the Wicklow Mountains. They are the subject of ongoing research by geophysical survey and excavation (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2017; O’Brien & O’Driscoll Reference O’Brien and O’Driscoll2017; Hawkes Reference Hawkes2018; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024; O’Driscoll Reference O’Driscoll2024; O’Driscoll et al. Reference O’Driscoll, Hawkes and O’Brien2024; Gabriel Cooney, pers. comm.). Hughstown consists of four concentric enclosures, enclosing an area of 8.2 ha. Spinans Hill 1 is a single enclosure consisting of a low bank enclosing an area of about 11 ha. At Rathcoran, two closely spaced banks enclose a pear-shaped area of 10.02 ha.

These new sites, along with the already known features of Magheraboy and Donegore, seem to fit well with the general repertoire of enclosures in southern Britain, probably involving multiple communities (Edmonds Reference Edmonds1999; Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Dyer and Barber2001; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011), and it is hard to resist the notion that these examples in Ireland were in some way inspired by practices in Britain, since that is the closest area with similar constructions of comparable date; those of northern France were both further away and not certainly still in use at the probable time of construction and use in Ireland (Dubouloz et al. Reference Dubouloz, Praud and Monchablon2023; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024). The known enclosures in Ireland are all relatively close to the coast. Within Britain, enclosures remain scarce north of mid-Wales and the English Midlands, though there are one or two outliers in north-west England and possible candidates in southern Scotland (Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Dyer and Barber2001; Brophy Reference Brophy, Cummings and Fowler2004; Peterson Reference Peterson2021; Frodsham Reference Frodsham2021; Oswald & Edmonds Reference Oswald and Edmonds2021). If there is a connection between Irish and British enclosures in the early Neolithic, it is thus tempting to look to southern Britain, where construction probably began in the late 38th century cal BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss and Healy2022; Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024), as the most likely source of inspiration for those built in Ireland. The southern British distribution extends to the Marches and southern Wales; many examples in those regions seem to be later than those to the east (Davis & Sharples Reference Davis and Sharples2017; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss and Healy2022), though Dorstone, Herefordshire, appears to be of 37th-century cal BC date (Ray et al. Reference Ray and Wiltshire2023). The Irish examples examined so far thus conform to the most recently modelled overall chronology for enclosures in Britain and Ireland as a whole (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024, fig. 4A).

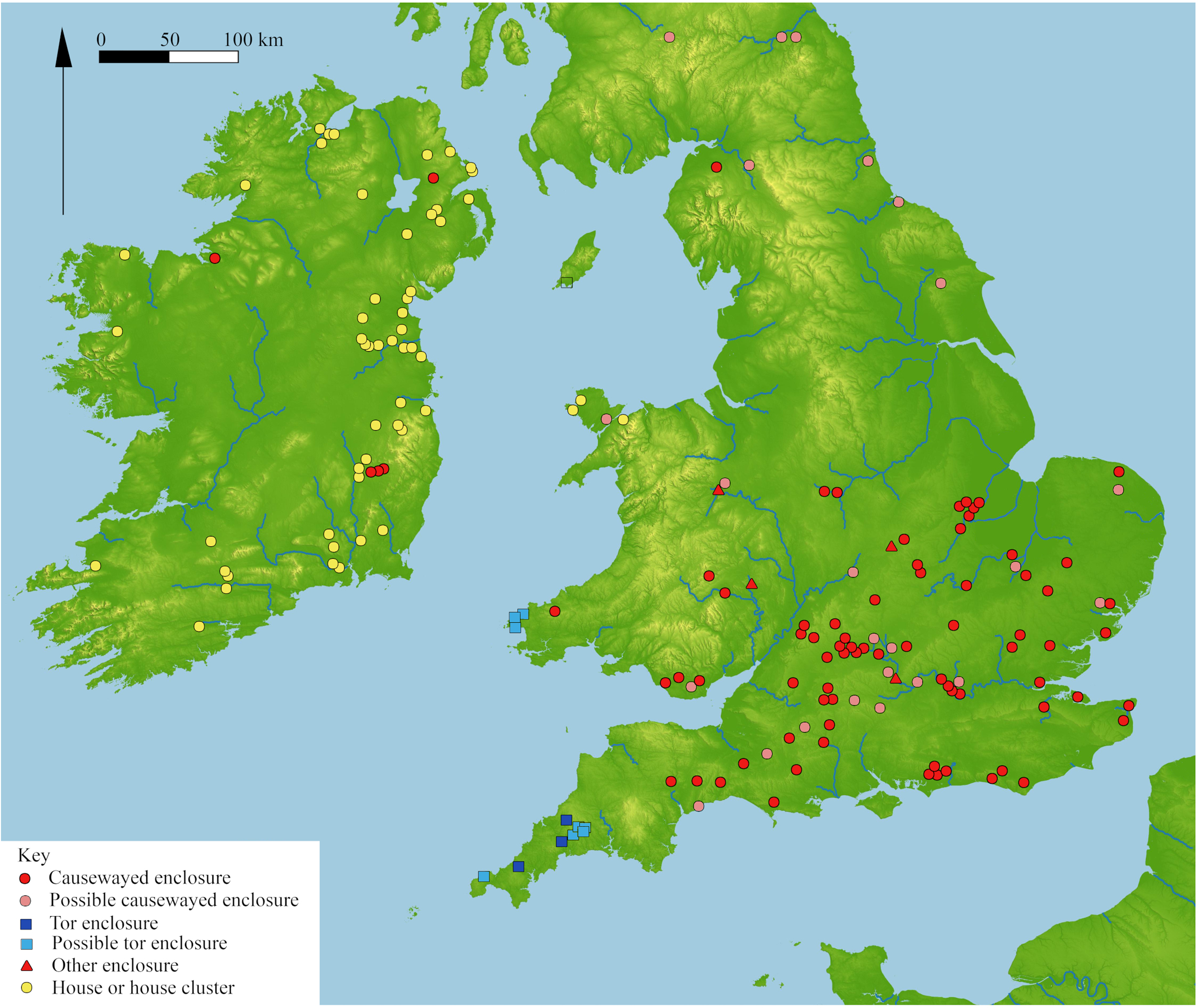

A last aspect to put in the mix are the respective distributions of houses and enclosures across the Irish Sea. Houses appear more or less across the whole of Ireland, in the so-called ‘house horizon’ of the later 38th to the later 37th century cal BC (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapter 12; Smyth Reference Smyth2014; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, McClatchie and Warren2020, 428). There is a marked cluster of new discoveries in north-west Wales (Kenney Reference Kenney2021). Other examples in western Britain are scattered from Cornwall to southern Scotland (Brophy Reference Brophy2007; Nowakowski & Johns Reference Nowakowski and Johns2015) and the Isle of Man (Bruce et al. Reference Bruce, Megaw and Megaw1947). Enclosures are concentrated principally across southern Britain, including in the Marches and south Wales (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss and Healy2022, fig. 13.1), with outliers in north-west England and Scotland as noted above. Put together, the two distributions are strikingly complementary (Figure 3). If their chronologies overlap (the house horizon in Ireland seeming to be a much shorter-lived phenomenon than enclosures), perhaps principally in the 37th century cal BC, could they represent some sort of equivalence in terms of sociality, such as an enhanced need or desire for larger gatherings and more prominent assertions of local, regional and other identities?

Fig. 3. Respective distributions of sites of the house horizon in Ireland and enclosures in Britain (after Smyth Reference Smyth2014; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss and Healy2022). For details of further houses in western Britain, and enclosures in Ireland, see the main text.

If all this deepens a sense of varied potential connections across the Irish Sea, then the future task remains of unpicking detailed histories of development. More modelling is required. Pending that, my third working proposition is that connections were established thick and fast near the start of the Irish sequence, in ENII, and may have intensified through time. Thus, the example of Poulnabrone (Lynch Reference Lynch2014) allows the presence of portal tombs from perhaps as early as c. 3800 cal BC; it seems very unlikely, however, that portal tombs are all this early. On the basis of present modelling, both Clyde cairns and court tombs appear to emerge at about the same time, from 3700 cal BC onwards (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Murphy, Jones and Warren2012; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020; cf. Cummings & Robinson Reference Cummings and Robinson2015). At least one house underlies a court tomb in Ballyglass, Co. Mayo (Ó Nualláin Reference Nualláin1972). Whether the central court tomb with its double set of chambers is of the earliest type is a moot question and it could be of 36th century cal BC date (Smyth Reference Smyth2020, 151), but on the slender basis of that one example, one could speculate whether some Irish houses preceded the first court tombs, just as seemingly halls in Scotland preceded the first Clyde cairns (Brophy Reference Brophy2007; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapter 14; Sheridan & Schulting Reference Sheridan and Schulting2020). The Donegore enclosure in Co. Antrim probably dates to the later 38th or earlier 37th century cal BC (Mallory et al. Reference Mallory, Nelis and Hartwell2011; Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, figs 12.5–6; Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024), though it is unlikely to predate the first enclosures in southern Britain (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss and Healy2022) and perhaps therefore falls in the later part of its possible start span (noted above). As such, it may have preceded the bulk of houses in the Irish house horizon. Where other enclosures fall is an open question, as Magheraboy does not have to be early, and the more recent discoveries are yet to be precisely dated.

While there is still a lot to sort out and pin down, a working sequence for Ireland could start with the first portal tombs, to be followed by the first houses, and then coming thick and fast, the first Clyde cairns, court tombs and enclosures, and perhaps soon after the first passage tombs (not found in mainland Scotland, but perhaps with echoes in Hebridean tombs: Hensey Reference Hensey2015; cf. Henley Reference Henley2004, 68–9). Although I have argued above for Neolithic people initially coming into Ireland from Britain, not all movement and connection need have been one-way. On distributional grounds alone, portal dolmens in Wales and south-west England could be an offshoot of the greater numbers in Ireland (in a distant echo of de Valera’s arguments (Reference de Valera1960) for a west–east spread of court tombs), and one can remember here Alison Sheridan’s suggestion (Reference Sheridan1995, 17) of Hembury ware in north-east Ireland; when the sequence comes in due course to decorated bowls (Case Reference Case1961; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1995), directionality of influence across the North Channel is also an open question. Lastly, the priority of axe production is hard to establish on either side of the Irish Sea (Cooney Reference Cooney2000; Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough and Schauer2020; Cooney et al. Reference Cooney, O’Neill, Revell, Gilhooly and Knutson2024) and early Neolithic cave use likewise may have begun at similar times, though there are some indications that the majority of Irish examples may be a little later than those in western Britain (Dowd Reference Dowd2015).

The politics of beginnings and connections

So far, I have advanced three propositions. The first is that the first Neolithic communities in Ireland came mainly via Britain, and presumably western Britain in particular. That idea goes back to the generation of Stuart Piggott and Humphrey Case, but it has largely been lost sight of in recent searches for continental sources common to both Britain and Ireland. Recent aDNA analyses reveal more or less identical genetic signatures for Britain and Ireland. My second proposition is that subsequent connections seen in material culture and monumentality are evidence of intense interaction across the Irish Sea in the early Neolithic, even running on into the middle Neolithic in Irish terminology. Such links have often been listed, and recent aDNA analyses serve to enhance these with suggestions of intermarriage and ongoing contact. I argue, however, that this has been presented in an oddly matter-of-fact and muted way, and that much more could and should be made of it. My third proposition is that these connections were spread over time, though this requires further dating and more modelling, and as such may well have intensified through time.

Those claims enable my fourth proposition, that the close and arguably intensifying links seen in the course of the early Neolithic on either side of the Irish Sea were as they were because of the conditions of the initial spread of the Neolithic way of life through Britain and Ireland. That may establish an illuminating contrast with the process of the initial Neolithisation of southern Britain from the Continent. Though again subject to the need for further dating and revised modelling, the start of the Neolithic in Britain, on the basis of current evidence going back to south-east England in the 41st century cal BC, may have developed gradually, area by area (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011, chapters 14 and 15, with changes in models noted above). There have also been claims for some kind of minimal initial Neolithic presence in southern Britain (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2018; Thomas Reference Thomas2022), though the details, such as the existence of cereal cultivation before 3800 cal BC, can be debated (Whittle Reference Whittle2024a; Reference Whittle2025). Though there are indications from both material culture similarities and aDNA analyses that Neolithic people may have come into southern Britain from northern France, it has been notoriously difficult over decades of research to pin down the whole range of possible continental sources for what came to be practised in Britain (Sheridan & Whittle Reference Sheridan and Whittle2023). This is further impeded by changing and potentially long-lasting ties in several directions; some even suggest possible contacts with and movements from and to southern Scandinavia, witnessed in the mutual presence of dolmens (Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Hofmann, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2022). Arguably, more visible for the first time with a refined chronology and improved scientific analysis, that classic difficulty may have been so because of the gradual, time-progressive nature of the process of the Neolithisation of Britain, at a time of considerable change and realignment across the adjacent Continent (eg Praud et al. Reference Praud, Bostyn, Cayol, Dietsch-Sellami, Hamon, Lanchon and Vandamme2018; Dubouloz et al. Reference Dubouloz, Praud and Monchablon2023). In contrast to that putatively more strung-out process, I see what happened across the Irish Sea as faster and more concentrated, and because of the circumstances of beginnings in this context, active connections were important, and were maintained and even extended over succeeding generations.

Here come the politics of connectivity. Comparative migration theory predicts both the conditions of initial scouting and pioneering, and the recurrent existence of ongoing migration streams and connections back to original homelands (eg Anthony Reference Anthony, Chapman and Hamerow1997). The evidence in the case of Britain itself is mixed. Ancient DNA analysis so far suggests little by way of continuing migration from the Continent after initial Neolithisation (Brace & Booth Reference Brace, Booth, Whittle, Pollard and Greaney2023; Booth Reference Booth, Hofmann, Cummings, Bjørnevad-Ahlqvist and Iversen2025), though isotope analysis has identified potential individual migrants (Neil et al. Reference Neil, Montgomery, Evans, Cook and Scarre2017; Reference Neil, Evans, Montgomery and Scarre2020); the introduction of enclosures into southern Britain at c. 3700 cal BC may also have evoked ancestral connections (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy, Bayliss and Cooney2024). How could the contrasting situation across the Irish Sea be explained? The power of connection with the distant in strategies of achieving social prominence might be summoned (Helms 1988; Reference Helms1998), but given the short distances and physical inter-visibilities across the North Channel it is a moot point whether that applies convincingly in this case. The argument has frequently been made for an important role for lineage heads or founders (eg Ray & Thomas Reference Ray and Thomas2018; Fowler Reference Fowler2022), and kinship can be a significant force for cohesion and solidarity in contexts of migration (Carsten Reference Carsten2020). However, such evidence as we possess may suggest a different kind of trajectory.

There was a lack of close biological relatives in both the early portal tomb at Poulnabrone and the probably slightly later court tomb at Parknabinnia, leading the investigators to ‘exclude small family groups as their sole proprietors and interpret our findings as the result of broader social differentiation with an emphasis on patrilineal descent’ (Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy and Bradley2020, 387). It is plausible that Penywyrlod in south-east Wales, probably dating from the 38th century cal BC onwards, also served a wide population, perhaps with multiple kinds of biological and social relationships, in a context of initial, pioneering inland settlement (Britnell & Whittle Reference Britnell and Whittle2022). The kind of lineage shown by recent aDNA analysis at Hazleton North in the Cotswolds (Fowler Reference Fowler2022; Fowler et al. Reference Fowler, Olalde, Cummings, Armit, Büster, Cuthbert, Rohland, Cheronet, Pinhasi and Reich2022) could have emerged through time (Whittle Reference Whittle2024b), and the same could be suggested, as a working hypothesis to be tested in future research, for many Clyde cairns and court tombs. Connections across the Irish Sea could have been intensified with time because emergent leading social groupings sought to make active use of a remembered history of beginnings, concentrated and intensive.

Within the now revised big picture of Neolithisation sketched at the beginning of this paper, I thus envisage different scenarios of change in different regions. What happened across the Straits of Dover and otherwise across the English Channel or North Sea was rather different to what took place across the North Channel and other parts of the Irish Sea, with an arguably slower tempo of change in the former case and a quicker and more intense transformation in the latter. I have argued that these led to the close connections across the Irish Sea, long observed but under-interpreted, and which are different to the history of subsequent connections between Britain and the Continent following initial colonisation. In virtually every sphere there are many remaining questions, but I have tried to make clear what we know (or think we know) and what we do not. I have advanced my four main propositions to help to frame continuing and future debate and research.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful above all to Gabriel Cooney for encouraging me to think about connectivity across the Irish Sea, and for his critical comments. Richard Bradley, Mike Copper, Duncan Garrow, the editors and two anonymous referees also gave invaluable critique of an earlier draft of the paper. Grateful thanks also to Mike Copper for the figures.