The SPARK study was launched in 2016 to recruit and retain a US cohort of autistic individuals and their family members [1]. Now with over 330,000 participants, including 130,000 autistic individuals, SPARK is the largest study of autism to date. As an online, recontactable cohort, SPARK represents a model for research infrastructure that enables researchers not only to access phenotypic and genetic data on thousands of individuals longitudinally but also to recruit individuals for additional research studies. As such, SPARK has become a catalyst for research and advancing the overall understanding of autism. For the research community more broadly, SPARK’s multimodal recruitment strategy can serve as a model for building other condition-specific, longitudinal research communities.

The Evolution of Epidemiologic and Clinical Research in the USA

Research recruitment in the USA has evolved considerably as population demographics have shifted over time and with the advent of new technologies. Historically, participants may have been recruited in person, from targeted locations or through traditional outreach methods, such as mailings and telephone calls, both of which may limit sample size and participation from diverse groups of people and affect the overall generalizability of findings. Ongoing longitudinal studies have had to adapt. For instance, the Framingham Study has focused on the epidemiology of heart disease in several generations from a single community for over 70 years [Reference Andersson, Johnson, Benjamin, Levy and Vasan2]. Over time, the study established two additional cohorts to address the racial and ethnic diversity limitations of the original cohort [Reference Tsao and Vasan3]. The Nurse’s Health Study is a longitudinal research study that began recruiting female nurses in the 1970s and has contributed significantly to knowledge of disease risk in women [Reference Colditz, Philpott and Hankinson4]. Now in its third phase, the study recruits nationally, includes both men and women, and is conducted entirely online, as compared to its original methodology that used a mailed survey [5].

Large-Scale Adoption of Online Research and Recruitment

Outside of the aforementioned studies, the advent of the internet and the penetration of smartphones and social media have enabled the recruitment of large (100k+) cohorts and the efficient collection of a greater breadth of data (including genomic). Specifically, the use of web-based registries allows rapid collection of data on both common and rare diseases or conditions at scale [Reference Mulder and Spicer6]. Online research is not without its limitations, however, including biases in enrollment [Reference Ashford, Eichenbaum and Williams7,Reference Leach, Butterworth, Poyser, Batterham and Farrer8].

Online recruitment, particularly through digital advertising and social media, has grown significantly. Studies have found online recruitment methods to be more efficient and cost-effective in comparison to “offline” methods [Reference Brøgger-Mikkelsen, Ali, Zibert, Andersen and Thomsen9–Reference Sanchez, Grzenda and Varias12]. A review by Frampton and colleagues assessed the relative contribution of digital tools in both participant recruitment and retention in clinical trials [Reference Frampton, Shepherd, Pickett, Griffiths and Wyatt13]. Their review found that the use of digital tools doubled in the past decade (from 2008 to 2018), the most common being social media, internet sites, email, television/radio, and text messaging. Limitations include waning engagement over time [Reference Christensen, Riis and Hatch10], less representativeness (i.e., less racially/ethnically/linguistically diverse, and higher socioeconomic status [Reference Benedict, Hahn, Diefenbach and Ford14,Reference Gerke, Tang and Cozier15]), and ineffectiveness in enrolling participants in clinical trials as compared to “offline” methods [Reference Brøgger-Mikkelsen, Ali, Zibert, Andersen and Thomsen9].

Of all social media channels, Facebook has been the most commonly utilized and effective recruitment platform [Reference Lee, Torok and Shand16,Reference Haikerwal, Doyle and Patton17]. Studies evaluating its effectiveness have found that paid ads using Facebook are superior in their ability to target a given geographic region or population [Reference Ahmed, Simon, Dempsey, Samaco and Goin-Kochel18–Reference Whitaker, Stevelink and Fear20], as well as re-engage participants who were lost to follow-up [Reference Haikerwal, Doyle and Patton17]. However, Facebook can be less cost-effective for recruiting diverse samples [Reference Pechmann, Phillips, Calder and Prochaska19] or biased toward White, female participants [Reference Whitaker, Stevelink and Fear20].

Recruitment of Vulnerable Populations

There are unique strategies and challenges associated with recruiting and retaining vulnerable populations in research. Regarding pediatric populations, the Healthy Communities Study [Reference Sagatov, John and Gregoriou21] and National Children’s Study [Reference Park, Winglee, Kwan, Andrews and Hudak22] are examples of epidemiological studies that recruited large, pediatric cohorts. Whereas the Healthy Communities Study recruited via schools, the National Children’s study adopted multipronged recruitment efforts that included household-based recruitment, provider-based recruitment, and direct outreach. Findings from these studies underscored the importance of adopting a multimodal approach to recruitment, particularly in obtaining a representative sample.

Challenges to online pediatric research include parent consent and pediatric assent [Reference Brothers, Clayton and Goldenberg23,Reference Kasperbauer and Halverson24], and in longitudinal studies, reconsenting and following children as they transition to adulthood. For instance, a pediatric biobank experienced challenges recruiting children, including re-consenting pediatric populations after they turned 18 [Reference Bourgeois, Avillach and Kong25]. Little is known about how best to recruit and retain emerging adults as well, but recent research suggests that recruitment through a range of strategies and engaging participants as partners may increase effectiveness [Reference LaRose, Reading, Lanoye and Brown26].

Finally, a challenge that is not unique to pediatric research is the recruitment and engagement of traditionally underrepresented groups, such as individuals with disabilities and racial and ethnic minority populations [Reference Hasson Charles, Sosa, Patel and Erhunmwunsee27]. Individuals with disabilities are routinely underrepresented in research because of physical, cognitive, and economic challenges and the added resources that may be required to accommodate their needs [Reference Jimoh, Ryan and Killett28,Reference Shariq, Cardoso Pinto, Budhathoki, Miller and Cro29]. For racial and ethnic minority communities, studies have shown that it is important to employ a range of community engagement strategies [Reference Cunningham-Erves, Joosten and Kusnoor30,Reference Wieland, Njeru, Alahdab, Doubeni and Sia31], as well as communicate both their unique contributions to research and the benefits conferred with their participation [Reference Lewis, Turbitt and Chan32–Reference Zamora, Williams, Higareda, Wheeler and Levitt34].

SPARK as a Model for Online, Longitudinal Research

Today there are several online, longitudinal studies collecting data (and in some cases, biosamples) on thousands of individuals. An example of a US-based study most comparable to SPARK in terms of recruitment methodology, size, and scope is the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us study [Reference Denny and Rutter35]. The All of Us study aims to recruit one million individuals in the USA. Participants can join online or in-person at one of the partner clinical sites, and participation includes providing self-reported information online as well as biosamples. However, the study currently only recruits adults. An example of a condition-specific online registry that enrolls both children and adults is the T1D Exchange, for type I diabetes [Reference Beck, Tamborlane and Bergenstal36]. There are also many rare disease registries that focus on smaller, pediatric populations (e.g., Simons Searchlight [37], Angelman syndrome [Reference Napier, Tones and Simons38], and FORWARD for Fragile X [Reference Sherman, Kidd and Riley39]).

The SPARK study has parallels with the aforementioned studies insofar as it is online, longitudinal, and multifaceted in its collection of both self-report data and biospecimens and its ability to recontact individuals. However, SPARK is unique in adopting a multimodal approach to recruit children and adults with autism and their family members that includes both centralized recruitment through large-scale, digital media efforts and partnerships with over 30 clinical sites throughout the country. Herein, we describe the major recruitment strategies of SPARK and evaluate their relative effectiveness with respect to recruitment of a core study population.

Materials and Methods

Study Enrollment and Procedures

The SPARK study is funded by the Simons Foundation and uses a single, central IRB (WCG IRB Protocol #20151664). The study is open to all individuals with a professional diagnosis of autism and their family members who live in the USA and who read and understand English or Spanish. The qualifying, professional diagnosis of autism is based on self/proxy report at study entry.

An illustration of the major steps of SPARK study participation is presented in Figure 1. Parents/legal guardians of children and dependent adults with autism and independent autistic adults can enroll online at https://SPARKforAutism.org. After creating an account, the individual, herein referred to as the “primary account holder,” consents to share their data and to be recontacted about future research opportunities, and, if applicable, indicates their child/dependent’s assent to share information about themselves for research.

Figure 1. Overview of SPARK study participation for primary account holdersa and study sample flow. a The SPARK study participant who initiates enrollment in SPARK on behalf of themselves and their family members. b Not shown are 6,505 participants who are part of a “completed biological family,” whereby the primary account holder, secondary account holder, and individual with ASD have all completed enrollment.

During registration, the “primary account holder” is also asked how they first heard about SPARK and is provided the following options: a clinical site/hospital/university, a community-based organization, the Interactive Autism Network (IAN), my healthcare provider (e.g., doctor or therapist), online (e.g., web page, Facebook, or other social media), through a media announcement (e.g., print, radio, or TV), a friend, invited by a family member, or other. The IAN, a similar online study, closed on June 30, 2019, and all existing participants were invited to join SPARK.

As a parent of a dependent child with autism, the “primary account holder” may also add non-autistic siblings of the individual with autism and is then asked to invite the other biological parent (or guardian), if available, to participate by providing their email address. The “primary account holder” must be over 18 years and, if a parent, the legally authorized representative of the child or dependent adult with autism. SPARK sends a separate email to the invited biological parent or “secondary account holder,” which includes instructions on how to join the study. The “primary account holder” and any minors/dependents are then invited to consent/assent to provide a saliva sample for DNA analysis and to receive genetic results, if desired. A saliva collection kit is shipped to the participant’s home at no cost to the family. Individuals are not required to participate in the genetic portion of the study to join SPARK. Autistic adult “primary account holders” follow a similar registration process whereby they consent for themselves and invite family members to participate.

Once online registration is complete, participants are asked to complete a series of demographic and behavioral or psychological questionnaires. The account dashboard is the participant’s study “home,” through which they access study consents, surveys, and tasks. Over time, participants may be invited to participate in additional research studies by external researchers through the SPARK Research Match program. Additional information about the SPARK study, including Research Match and the return of genetic findings to participants, can be found on the study’s website, https://sparkforautism.org/ [1].

Recruitment Strategies

Clinical sites

SPARK funds a network of clinical recruitment sites throughout the USA. These sites are predominantly located at major academic medical centers that specialize in autism and other developmental disabilities. All sites have a site principal investigator and at least one research coordinator. Each clinical site has their own unique study URL (e.g., https://SPARKforAutism.org/TCH), which enables centralized tracking of all recruitment sites. The site’s primary role is to recruit individuals with autism and their biological family members into SPARK and support enrollment completion (e.g., assist with registration and/or saliva collection).

Digital advertising

SPARK advertises on Google, Bing, and through other platforms that utilize embedded algorithms to display ads for the SPARK study near similar (i.e., autism-focused) content. SPARK Google Ads Manager and Bing accounts display ads based on an autism-related search term or terms entered. Individuals also may learn about SPARK organically (i.e., through manual search).

Social media

SPARK has accounts on the following social media channels: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn. Individuals can learn about and join SPARK organically (e.g., by viewing a friend’s post about SPARK in a feed) or by viewing and clicking a boosted post or paid ad on Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube. A boosted post differs from a paid ad in that it appears in SPARK’s newsfeed and can be delivered (or “boosted”) to a given audience for a fee. Ads have greater customization features but require setup through Meta’s Ads Manager program [40]. SPARK posts include static photos, GIFs, and videos and range in content from information about the SPARK study to person- or family-first accounts of their participation in SPARK.

Traditional and digital media

Since its inception, the SPARK study has been featured on national and local television, radio, and newspaper outlets, both print and digital. The SPARK central team typically drafts a press release, which is then added to an online press distribution platform and picked up by interested channels. SPARK has employed both marketing and public relations firms.

Organizational and community outreach

The major autism support and advocacy organizations in the USA, such as the Autism Society of America, as well as local, community-based groups, or individuals (i.e., bloggers) have links to SPARK included in their websites. Additionally, the following organizations have a unique study URL to enable tracking of SPARK participants through their specific channels: The Arc, Arkansas Autism Resource and Outreach Center, Autism Services & Resources Connecticut, Autism Speaks, Autism Society North Carolina, ASA Heartland, Easter Seals, GRASP, IAN, the Kentucky Autism Training Center, Mid-Michigan Autism Association, and Washington Autism Alliance & Advocacy.

Measures

Participant characteristics

The study activities reported herein focused on the “primary account holder,” defined as the individual who first joins SPARK on behalf of the family and is assigned the majority of study tasks to complete on behalf of themselves and their dependents.

The following sociodemographic characteristics, collected during online registration or through subsequent study tasks, were used to characterize the “primary account holder:” age at registration; sex at birth; autism diagnosis (Y/N); ethnicity; race; US census region derived from participant-reported residence; metropolitan area based on 2013 Urban Influence Codes that define metropolitan counties by population size of their metro area [41]; and the area deprivation index (ADI). The ADI is derived from participant-reported addresses and constructed by ranking the ADI from low to high for the nation and grouping the block groups/neighborhoods into bins corresponding to each 1% range of the ADI. A block group with a ranking of 1 indicates the lowest level of “disadvantage” within the nation, and an ADI with a ranking of 100 indicates the highest level of “disadvantage” [Reference Kind and Buckingham42].

Recruitment strategies

We defined SPARK recruitment strategies in the following ways: (1) clinical site referral (Y/N); (2) the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) referrer or the web address a user last visited before the SPARK site [43]; and (3) response to the single-choice question at the start of online registration, “How did you hear about us?” (see “Study enrollment and procedures” in Methods). Participants referred by a clinical site either clicked on or entered a site-specific URL in their browser or selected a specific clinical site from a dropdown menu. Free text responses from those who responded “other” to the question “How did you hear about us?” were then manually coded and grouped with either one of the aforementioned categories or labeled “unknown.” Available HTTP referrer links were manually grouped into the following mutually exclusive categories: Facebook or Instagram; Google or other search engine; SPARK website; clinical site URL; clinical site website; community organization; news story; invited parent link; and email link. The presence or absence of the HTTP referrer link (Y/N) was also coded. Missing URL information typically means that the origin site included code in the HTML that omits referrer information [43].

Enrollment

Enrollment completion was defined as a participant who completes online registration, including both the data and genetic consent, and returns their saliva kit.

Core study participant

As SPARK collects both phenotypic and genetic information from participants, the value of the data increases with the breadth and depth of information associated with each participant. Therefore, those who have provided a saliva sample in addition to completing a core set of tasks for SPARK are considered “core participants.” For this study, a core study participant is defined as the primary account holder who completes enrollment and the Basic Medical Screening Questionnaire (BMSQ; see supplemental materials). The BMSQ is available on the participant Dashboard immediately after completing registration, is administered to every SPARK participant, and includes questions about pregnancy, birth complications, medical issues, and developmental and behavioral conditions.

Complete family enrollment

As SPARK enables participation of the entire family, we also assessed complete family enrollment, defined as the fully consented, primary account holder, an invited second parent, and a child or dependent with autism who completed online registration and returned their saliva kits.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses included measures of central tendency (e.g., means and proportions). Bivariate tests (e.g., chi-square and one-way analysis of variance tests) between the primary dependent variables (enrollment completion, core participant status, and family enrollment completion) and all participant characteristics were performed to identify which covariates to include in the multivariable regression analyses. Those with differences that were significant at a p-value of 0.05 or less were included in the multivariable models.

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds of enrollment completion, core participant status, and family enrollment by recruitment strategy. For these models, clinical site referral, the website used to join SPARK, and how a participant heard about SPARK were used as distinct primary independent variables. If a participant joined through a clinical site URL, they were automatically assigned “clinical site/hospital/university” in the “How did you hear about us?” dropdown menu, irrespective of whether they may have heard about SPARK in other ways. In contrast, for those not referred by a clinical site, participants were able to select from any of the options presented. Therefore, the relationships between how a participant heard about SPARK and the outcome measures were examined only in those who joined from the community at large (i.e., not referred by a clinical site).

For this study, we focused on core participant status as the primary outcome of interest, reporting only key differences observed from the regression models using enrollment completion and complete family enrollment. Further, in order to examine how the relationships between our recruitment strategies and primary outcome of interest differed in primary account holders with and without a self-reported autism diagnosis, stratified analyses were also performed, and only key differences are reported herein. Detailed findings related to enrollment completion and complete family enrollment for the entire sample and related to core participant status for autistic and non-autistic account holders are presented in supplemental tables.

Lastly, during the period analyzed herein, race and ethnicity information was only collected via a Dashboard questionnaire called the “Background History Questionnaire.” Because of the relatively low completion rate for that questionnaire, race and ethnicity data were missing on roughly 74% of participants. While these variables were included in the analysis to better understand the relationship between race and ethnicity and our primary outcome measures, we appreciate that this variable is also a confounder, as providing the information in and of itself may be considered a proxy for increased study engagement. Therefore, for each relationship examined, we presented findings from two multivariable regression models – one with race and ethnicity and one without. SPARK data release version 9 was used and analyzed with Stata/SE version 18.0 [44].

Sample

As of July 2023, there were a total of 189,000 account holders in SPARK (excluding all dependents, i.e., minors with and without autism). While the study has been recruiting participants since December 2015, it started large-scale digital and social media advertising in February 2018. In addition, on May 29, 2019, every individual who joined SPARK was automatically referred to a clinical site based on their zip code. Prior to this change, participants were linked to a clinical site only if they joined through a unique site URL or selected “clinical site/hospital/university” from the “How did you hear about us?” question. A total of 64,762 individuals created an account during the period analyzed herein.

In order to evaluate the associations with joining through a clinical site or other method, the study sample was restricted to all primary account holders, that is, the independent adult who first joined SPARK on behalf of his or her family members and responsible for completing the majority of study tasks, who joined after January 31, 2018 and before May 29, 2019. The final study sample included 31,715 data consented, primary account holders. Lastly, the sample did not include account holders who were recruited into SPARK but subsequently chose to withdraw or whose data were held back from public release due to identified phenotypic data flags (2,065 as of July 2023).

Results

Participant Characteristics

The average age at study registration for the primary account holder was 38.5 years (SD 9.0), and 86% were female (Table 1). Eight percent self-reported an autism diagnosis. Among the 26% who reported ethnicity and race, 15% were Hispanic and the majority were White (80%). The plurality of participants reported living in the South (37%), with only 12% in a non-Metropolitan area. The mean ADI was 48.8 (SD 25.7), indicating slightly lower deprivation compared to the median of 50.0.

Table 1. Characteristics of primary account holders a in SPARK (N = 31,715)

a The SPARK study participant who initiates enrollment in SPARK on behalf of themselves and their family members.

Study Completion

Of the 31,715 primary account holders who joined the SPARK study during the study period, 88% completed online registration (and both the data and genetic consents), 46% completed enrollment (online registration and returned saliva sample), and 38% were defined as core participants (Fig. 1). Lastly, 21% of all primary account holders were part of complete families (completed enrollment for both biological parents and the child with autism).

Recruitment Strategies

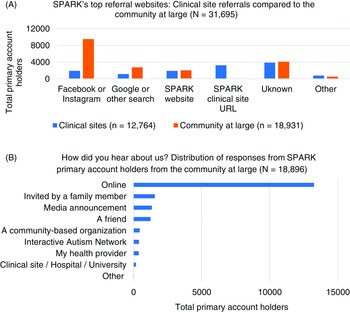

With respect to recruitment method (Fig. 2), 40% of all participants were referred by clinical site. Of participants with available URL data (75%), the top websites used to join the study were Facebook or Instagram (48%), the SPARK website (16%), Google or other search engines (16%), and SPARK clinical site URLs (14%). When including those whose URL data were unknown, the top three reported referral sites were Facebook and Instagram (36%), Unknown (25%), and the SPARK website and Google and other search (both at 12%). Among participants who joined from the community at large, most heard about SPARK online (70%), followed by being invited by a family member (8%), or through a media announcement (7%).

Figure 2. Recruitment sources in SPARKa. a Recruitment sources for primary account holders, defined as the SPARK study participant who initiates enrollment in SPARK on behalf of themselves and their family members, include (A) the referral website used by SPARK participants who joined through a clinical site versus the community at large (n = 31,695; missing data excluded) and (B) the response to “How did you hear about us?” from the community at large only (n = 18,896; unknown responses are not included). Individuals who joined SPARK through a clinical site were automatically assigned to the “clinical site/hospital/university” response category and are therefore not represented here.

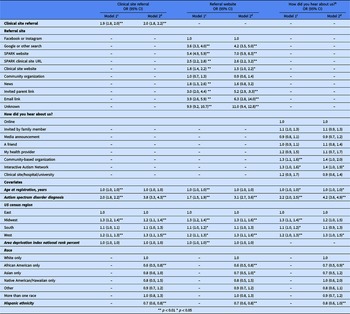

Clinical Site Referral and Core Participant Status

In both models with and without race and ethnicity, clinical site referral was associated with a two times increased odds of being a core participant, adjusting for autism diagnosis, age at registration, census region, ADI, and in model 2, race and ethnicity (Table 2; Fig. 3). For both models, an autism diagnosis was associated with an increased odds of being a core participant, as was living in the Midwest or West, as compared to the East. In model 2, both African American race and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with a significant decreased odds of core participant status.

Figure 3. Adjusted odds of core participant status among primary account holders in SPARK, by recruitment method (N = 31,715)a. a The SPARK study participant who initiates enrollment in SPARK on behalf of themselves and their family members; How did you hear about us? Include the community at large only (N = 18,945); CI = confidence interval; REF = reference group; all models adjusted for sex at birth, age at registration, autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, area deprivation index national rank, and US census region.

Table 2. The relationship between recruitment method and core participant status among primary account holders a in SPARK (N = 31,715)

a The SPARK study participant who initiates enrollment in SPARK on behalf of themselves and their family members.

b Community at large only (N = 18,945).

c Without race and ethnicity.

d With race and ethnicity.

Referral Site and Core Participant Status

Compared to joining through Facebook or Instagram, participants were significantly more likely to be core participants if they joined through Google, the SPARK website, a SPARK clinical site URL, an invited parent link, or an email link in both models (Table 2; Fig. 3). Joining from a news story was associated with a significant increased odds of enrollment completion in model 1 only. For both models, an autism diagnosis was associated with an increased odds of being a core participant, as was living in the Midwest or West. In model 2, African American race, Asian race, and Hispanic ethnicity were all associated with a significant decreased odds of being a core participant.

How a Participant Heard about SPARK and Core Participant Status Among the Community at Large

Compared to hearing about SPARK “online,” the only sources significantly associated with an increased odds of core participant status were the IAN and community-based organizations (Table 2; model 1 only; Fig. 3). In both models, a self-reported autism diagnosis and living in the West (Midwest and South in model 1 only) were associated with an increased odds of core participant status. African American race and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with a decreased odds of being a core participant in model 2.

Key Differences Using Enrollment Completion and Complete Family Enrollment as Outcomes

The relationships between clinical site referral and enrollment completion (Supplementary Table s1) and clinical site referral and complete family enrollment (Supplementary Table s2) were stronger compared to the observed site referral and core participant relationship. An autism diagnosis, older age at registration, and male sex at birth were all associated with a decreased odds of family enrollment, whereas Asian race was associated with an increased odds. In the referral site and family enrollment models, the same relationships between the aforementioned covariates were observed. Lastly, in the how a participant heard about us and family enrollment model, Asian race was not associated with complete family enrollment.

Recruitment Strategies and Core Participant Status Stratified by Autism Diagnosis

The relationship between clinical site referral and core participant status among non-autistic primary account holders (Supplementary Table s3) was comparable to that observed in the combined analysis and moderately attenuated in the autistic only sample (Supplementary Table s4). In the referral site and core participant model, directly visiting the SPARK website, being invited by another parent, and clicking on an email link (vs. social media) were the strongest predictors of core participant status for the non-autistic samples. For autistic primary account holders, Google or other search, directly visiting the SPARK website and using an invited parent link (model 2 only) were the strongest predictors of core participant status. For the non-autistic primary account holders who were not referred by a clinical site (i.e., from the community at large), hearing about SPARK through a community-based organization (model 1) or IAN (model 2) were associated with an increased odds of core participant status. For the autistic adult account holders, IAN was the only predictor of core participant status (model 1).

Discussion

Overall, primary account holders (parents of a dependent with autism or an independent adult with autism) who completed online registration, provided a biospecimen, and completed the baseline questionnaire, defined as “core participants” in this study, were more likely to have been referred by clinical site and clicked on a link other than Facebook or Instagram. These same participants were also significantly more likely to live in the Midwest or Western regions of the USA and less likely to be African American and Hispanic. Among those coming from the community at large rather than from a clinical site, both community-based organizations and a referral from the IAN were associated with increased likelihood of reaching core participant status.

Findings from this study suggest that having personal assistance from or some connection to a clinical site enhances study enrollment and task completion in online research. In particular, complex, multistep enrollment processes and family member enrollment may be more readily completed with the support of in-person study staff to facilitate participant completion of study tasks. Furthermore, despite high fixed personnel costs, the effectiveness of in-person recruitment may be worthwhile if large numbers of participants can be enrolled at the site.

There may also be greater trust among potential participants to join and remain engaged in a study if it is associated with a known medical institution or their own healthcare provider. The same logic may also apply to participants who heard about SPARK from the IAN. Those recruited at large who first heard about SPARK through IAN were significantly more likely to be core participants, particularly autistic adults. While their study engagement in SPARK may be confounded by their previous participation in autism research, referral by a trusted source, and not necessarily in-person, may be an important factor for some groups, particularly the autistic adult community.

Overall, while this study demonstrated that participants referred by clinical sites were more likely to complete enrollment, be core participants, and complete family enrollment, the exact strategies employed by the SPARK clinical sites were not assessed here. However, more detailed analysis of recruitment strategies used by SPARK clinical sites and how both research staff and participants perceived these approaches were assessed in our companion paper (unpublished data); results corroborate our current findings that personal support offered by research teams, particularly in connection with participants’ medical providers, can successfully engage and retain participants through study completion. Additional research is needed to better understand the different approaches that clinical sites undertook to recruit these participants.

The value of digital media, and social media in particular, to participant recruitment in online research should not be understated. The overwhelming majority of participants heard about SPARK “online,” and over 35% joined through Facebook or Instagram. Other studies have found that recruitment through social media channels like Facebook and Instagram are efficient [Reference Christensen, Riis and Hatch10,Reference Sanchez, Grzenda and Varias12] and result in the largest pool of eligible participants compared to other methods [Reference Darmawan, Bakker, Brockman, Patten and Eder11,Reference Parker, Hunter, Bauermeister, Bonar, Carrico and Stephenson45]. As demonstrated in this study, however, social media alone does not result in a greater likelihood of enrollment or study task completion as compared to online searchers for the SPARK study or visiting the study site directly.

Meta-analyses support that adopting multiple recruitment strategies, such as combinations of “online” and “offline” or “active” (i.e., direct outreach) and “passive” (i.e., digital or out of home advertisements) methods, increase the likelihood of meeting recruitment goals [Reference Brøgger-Mikkelsen, Ali, Zibert, Andersen and Thomsen9,Reference Davis and Bekker46]. Whether a study chooses to adopt recruitment strategies that are resource-intensive, such as employing in-person study personnel, or those that are more scalable and reach larger numbers, such as social media advertising, will depend largely on the goals of the study and burden of study participation in the short and long term. Additionally, there are other factors, including time, geography, and characteristics of a given study population that will likely influence which recruitment strategies to adopt. In a study like SPARK that enables a participant to, in essence, “choose your own adventure,” we found that a multimodal approach to recruitment was needed. Findings from this study demonstrate that a mix of both high- and low-resource-intensive strategies is optimal for recruiting large numbers of participants who are requested to complete multiple study tasks, including providing a biospecimen.

With respect to the characteristics of SPARK account holders who were more likely to become core participants, findings are consistent with other studies that show that engaged participants, particularly those recruited online and/or participating in online research, are more likely to be female and White [Reference Ashford, Eichenbaum and Williams7,Reference Benedict, Hahn, Diefenbach and Ford14,Reference Whitaker, Stevelink and Fear20]. In our study, African American and Hispanic participants were significantly less likely to complete enrollment, reach core participant status, or complete family enrollment. Interestingly, while Asian families in SPARK were less likely to reach core participant status, they were more likely to have complete family enrollment. These different outcomes speak to a need to develop specific, culturally informed approaches to recruitment and engagement in research for distinct communities versus a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Indeed, in recent years, there has been more research on effective engagement of racial and ethnic minority communities that highlight the need for more localized, participatory, and community-informed strategies to recruit and retain under-represented groups [Reference Zamora, Williams, Higareda, Wheeler and Levitt34,Reference Beech, Bruce, Crump and Hamilton47]. In an effort to increase representation of these communities and build a cohort that more closely resembles the US population, SPARK has recently implemented a comprehensive diversity, equity, and inclusivity (DEI) initiative that includes additional support to clinical sites, targeted marketing campaigns, and a DEI advisory board. Research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these efforts in recruiting a representative cohort. Ultimately, studies like SPARK have a responsibility to work closely with key stakeholders and community groups, not only to overcome structural barriers to study participation, like access to the internet, but also to address the nuanced cultural barriers and historical trauma experienced by so many communities, to achieve true representation in research.

When compared to findings from other contemporaneous, national online disease registries, many of SPARK’s findings are comparable. For instance, the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) Cancer Prevention Study 3, which enrolled over 300,000 individuals at highly publicized and well-staffed ACS events throughout the country, found few differences comparing participants who partially versus fully enrolled [Reference Patel, Jacobs and Dudas48]. However, like the SPARK study, they observed significantly greater participation among White females. The Sister Study Cohort recruited over 50,000 females across the USA using several diverse recruitment methods [Reference Sandler, Hodgson and Deming-Halverson49]. Like the SPARK and CPS-3 cohorts, participants were more likely to be non-Hispanic, White, and similar to SPARK to be recruited from the Midwest and Southern regions of the USA. In the Brain health registry of over 100,000 participants, African American, Asian, and Latino participants were significantly less likely than their White counterparts to complete the baseline questionnaires, comparable to this study’s findings related to core participants [Reference Weiner, Nosheny and Camacho50]. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of participants were female. Similar to the aforementioned studies, the Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry, a study of over 300,000 individuals, was comprised of predominantly White, non-Hispanic females [Reference Langbaum, High, Nichols, Kettenhoven, Reiman and Tariot51]. Like SPARK, the APR employed a number of different recruitment strategies, of which paid social was responsible for bringing in the plurality (39%) of participants. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of those who joined through social media failed to reengage over time. Collectively, like SPARK, these studies succeeded in their efforts to recruit tens of thousands of individuals by employing a range of both national and geographically targeted passive and active recruitments studies. However, they all observed disparities in participation by gender, race, and ethnicity, which in many cases, extended to outcomes related to study task completion and longitudinal engagement. A comprehensive assessment of what these and other studies, particularly those with a focus on reaching underrepresented groups, have implemented and evaluated in this area may help to inform future efforts at achieving greater representation in disease registry research.

Findings from this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the SPARK cohort is based on parent- or self-reported autism diagnosis, and diagnoses have not been systematically validated across the entire cohort. However, a recent verification study using electronic medical record data was able to confirm autism in 98.8% of a SPARK sample [Reference Fombonne, Coppola, Mastel and O’Roak52]. Second, SPARK is not a population-based study and, as such, findings are not representative of the entire population of individuals with autism and their families in the USA. However, characteristics of children with autism in the SPARK sample, such as the ratio of males to females, and age at diagnosis, closely mirror those of other large cohorts (i.e., the CDC Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network [Reference Maenner, Warren and Williams53]). Lastly, an important consideration in identifying and prioritizing recruitment strategies is cost, which this study did not assess.

Since its national launch in 2016, the SPARK study has enrolled hundreds of thousands of research participants and their family members by employing a multifaceted recruitment strategy that combines a national network of clinical sites with large-scale digital and social media outreach. SPARK’s multimodal recruitment strategy can serve as a model for building other complex, longitudinal research communities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2023.697.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the individuals and families in SPARK, the SPARK clinical sites, advisory boards, and SPARK staff. We thank the following members of The SPARK Consortium for their efforts in creating, recruiting, and maintaining the SPARK cohort: Alexandria Aarrestad, Leonard Abbeduto, Gabriella Aberbach, Shelley Aberle, John Acampado, Andrea J. Ace, Adediwura Adegbite, Debbie Adeniji, Maria Aguilar, Kaitlyn Ahlers, Charles Albright, Michael Alessandri, Zach Algaze, Jasem Alkazi, Raquel Amador, David Amaral, Alpha Amatya, Logan Amon, Leonor Amundsen, Alicia Andrus, Claudine Anglo, Robert Annett, Adam Arar, Jonathan Arnold, Ivette Arriaga, Eduardo Arzate, Raven Ashley, Leilemah Aslamy, Irina Astrovskaya, Kelli Baalman, Melissa Baer, Ethan Bahi, Joshua Bailey, Zachary Baldlock, Elissa Ball, Grabrielle Banks, Gabriele Baraghoshi, Nicole Bardett, Sarah Barns, Mallory Barrett, Yan Bartholomew, Asif Bashar, Heidi Bates, Katie Beard, Juana Becerra, Malia Beckwith, Paige Beechan, Landon Beeson, Josh Beeson, Brandi Bell, Monica Belli, Dawn Bentley, Natalie Berger, Anna Berman, Raphael Bernier, Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, Mary Berwanger, Shelby Birdwell, Elizabeth Blank, Rebecca Bond, Stephanie Booker, Aniela Bordofsky, Erin Bower, Lukas Bowers, Catherine Bradley, Heather Brayer, Stephanie Brewster, Elizabeth Brooks, Jannylyn Brown, Hallie Brown, Alison Brown, Melissa Brown, Catherine Buck, Cate Buescher, Kayleigh Bullon, Joy Buraima, Gabi Burkholz, Martin Butler, Eric Butter, Amalia Caamano, Nicole Cacciato, Wenteng CaI, Katina Calakos, Norma Calderon, Kristen Callahan, Alexies Camba, Claudia Campo-Soria, Giuliana Caprara, Paul Carbone, Laura Carpenter, Sarah Carpenter, Lindsey Cartner, Myriam Casseus, Lucas Casten, Sullivan Catherine, Alyss Cavanagh, Ashley Chappo, Sonny Chauhan, Kimberly Chavez, Randi Cheathem-Johnson, Tia Chen, Wubin Chin, Sharmista Chintalapalli, Daniel Cho, Dave Cho, YB Choi, Nia Clark, Renee Clark, Marika Coffman, Cheryl Cohen, Laura Coleman, Kendra Coleman, Alister Collins, Costanza Columbi, Joaquin Comitre, Stephanie Constant, Arin Contra, Sarah Conyers, Lindsey Cooper, Cameron Cooper, Leigh Coppola, Allison Corlett, Lady Corrales, Dahriana Correa, Hannah Cottrell, Michelle Coughlin, Eric Courchesne, Dan Coury, Deana Crocetti, Carrie Croson, Judith Crowell, Joseph Cubells, Sean Cunningham, Mary Currin, Michele Cutri, Sophia D’Ambrosi, Giancarla David, Ayana Davis, Sabrina Davis, Nickelle Decius, Andrea Deisher, Jennifer Delaporte, Lindsey DeMarco, Brandy Dennis, Alyssa Deronda, Esha Dhawan, Gabriel Dichter, Christopher Diggins, Emily Dillon James Dixie, Ryan Doan, Kelli Dominick, Leonardo Dominquez Ortega, Erin Doyle, Andrea Drayton, Megan DuBois, Johnny Dudley, Gabrielle Duhon, Grabrielle Duncan, Amie Duncan, Megan Dunlevy, Meaghan Dyer, Rachel Earl, Dominique Earle, Catherine Edmonson, Sara Eldred, Nelita Elliott, Brooke Emery, Malak Enayetallah, Barbara Enright, Sarah Erb, Craig Erickson, Amy Esler, Liza Estevez, Anne Fanta, Carrie Fassler, Ali Fatemi, Faris Fazal, Marilyn Featherston, Jonathan Ferguson, Michael Finlayson, Angela Fish, Kate Fitzgerald, Chris Fleisch, Kathleen Flores, Eric Fombonne, Margaret Foster, Tiffany Fowler, Emma Fox, Emily Fox, Sunday Francis, Margot Frayne, Sierra Froman, Laura Fuller, Virginia Galbraith, Dakota Gallimore, Ariana Gambrell, Swami Ganesan, Vahid Gazestani, Madeleine R. Geisheker, Alicia Geng, Jennifer Gerdts, Daniel Geschwind, Mohammad Ghaziuddin, Haidar Ghina, Jessica Giulietti, Erin Given, Mykayla Goetz, Alexandra Goler, Jared Gong, Kelsey Gonring, Natalia Gonzalez, Antonio Gonzalez, Ellie Goodwill, Rachel Gordon, Carter Graham, Catherine Gray, Tunisia Greene, Ellen Grimes, Anthony Griswold, Luke Grosvenor, Pan Gu, Janna Guilfoyle, Amanda Gulsrud, Jaclyn Gunderson, Chris Gunter, Sanya Gupta, Abha Gupta, Anibal Gutierrez, Frampton Gwynette, Ghina Haidar, Melissa Hale, Monica Haley, Jake Hall, Lauren K. Hall, Jake Hall, Kira Hamer, Piper Hamilton, Bing Han, Nathan Hanna, Antonio Hardan, Christina Harkins, Eldric Harrell, Jill Harris, Nina Harris, Danaizha Harvey, Caitlin Hayes, Braden Hayse, Teryn Heckers, Kathryn Heerwagen, Daniela Hennelly, Lynette Herbert, Luke Hermle, Briana Hernandez, Jessica Hernandez, Clara Herrera, Amy Hess, Michelle Heyman, Lorrin Higgins, Brittani Hilscher Phillips, Kathy Hirst, Theodore Ho, Dabney Hofammann, Emily Hoffman, Margaret Hojlo, Alison Holbrook, Makayla Honaker, Jane Hong, Michael Hong, Gregory Hooks, Susannah Horner, Danielle Horton, Melanie Hounchell, Dain Howes, Lark Huang-Storm, Samantha Hunter, Hanna Hutter, Emily Hyde, Teresa Ibanez, Kelly Ingram, Dalia Istephanous, Suma Jacob, Andrea Jarratt, Stanley Jean, Anna Jelinek, Bill Jennsen, Mary Johnson, Erica Jones, Mya Jones, Garland Jones, Mark Jones, Alissa Jorgenson, Roger Jou, Jessyca Judge, Luther Kalb, Taylor Kalmus, Sungeun Kang, Elizabeth Kangas, Stephen Kanne, Oumou Kanoute, Hannah Kaplan, Sara Khan, Sophy Kim, Annes Kim, Alex Kitaygordsky, Cheryl Klaiman, Adam Klever, Hope Koene, Tanner Koomar, Misia Kowanda, Melinda Koza, Sydney Kramer, Meghan Krushena, Eva Kurtz-Nelson, Elena Lamarche, Erica Lampert, Martine Lamy, Rebecca Landa, Alex E. Lash, Noah Lawson, Alexa Lebron-Cruz, Holly Lechniak, Soo Lee, Bruce Leight, Matthew Lerner, Laurie Lesher, Courtney Lewis, Hai Li, Deana Li, Robin Libove, Natasha Lillie, Danica Limon, Desi Limpoco, Melody Lin, Sandy Littlefield, Nathan Lo, Brandon Lobisi, Laura Locarno, Nancy Long, Bailey Long, Kennadie Long, Marilyn Lopez, Taylor Lovering, Ivana Lozano, Marti Luby, Daniella Lucio, Addie Luo, My-Linh Luu, Audrey Lyon, Julia Ma, Natalie Madi, Malcolm Mallardi, Lacy Malloch, Anup Mankar, Reanna Mankaryous, Lori Mann, Patricia Manning, Julie Manoharan, Alvin Mantey, Olena Marchenko, Richard Marini, Alexandra Marsden, Clarissa Marwali, Gabriela Marzano, Andrew Mason, Sarah Mastel, Sheena Mathai, Emily Matthews, Emma Matusoff, Clara Maxim, Caitlin McCarthy, Lynn McClellen, Nicole Mccoy, James McCracken, Kaylen McCullough, Brooke McDonald, Julie McGalliard, Anne-Marie McIntyre, Brooke McKenna, Alexander McKenzie, Megan McTaggart, Hannah Meinen, Sophia Melnyk, Alexandra Miceli, Sarah Michaels, Jacob Michaelson, Estefania Milan, Melissa Miller, Anna Milliken, Kyla Minton, Terry Mitchell, Amanda Moffitt Gunn, Sarah Mohiuddin, Gina Money, Gabriela Montanez, Jessie Montezuma, Lindsey Mooney, Margo Moore, Amy Morales-Lara, Kelly Morgan, Hadley Morotti, Michael Morrier, Maria Munoz, Ambar Munoz Lavanderos, Shwetha Murali, Karla Murillo,Kailey Murray, Vincent J. Myers, Erin Myhre, Natalie Nagpal, Jason Neely, Emily Neuhaus, Olivia Newman, Darnell Newsum, Ai Nhu Nguyen, Richard Nguyen, Victoria Nguyen, Ai Nhu Nguyen, Evelyn Nichols, Amy Nicholson, Melanie Niederhauser, Megan Norris, Shai Norton, Kerri Nowell, Kaela O’Brien, Eirene O’Connor, Mitchell O’Meara, Molly O’Neil, Brian O’Roak, Edith Ocampo, Cesar Ochoa-Lubinoff, Anna Oft, Jessica Orobio, Elizabeth Orrick, Crissy Ortiz, Opal Ousley, Motunrayo Oyeyemi, Lillian Pacheco, Valeria Palacios, Samiza Palmer, Isabella Palmeri, Katrina Pama, Juhi Pandey, Anna Marie Paolicelli, Jaylaan Parker, Morgan Patterson, Melissa Patxot, Katherine Pawlowski, Ernest Pedapati, Michah Pepper, Esmeralda Perez, Jeremy Perrin, Christine Peura, Diamond Phillips, Karen Pierce, Joseph Piven, Juhi Plate, Jose Polanco, Jibrielle Polite, Natalie Pott-Schmidt, Tiziano Pramparo, Taleen Pratt, Lisa Prock, Stormi Pulver White, Hongjian Qi, Shanping Qiu,Eva Queen, Marcia Questel, Ashley Quinones, Nihal Raman, Desiree Rambeck, Rishiraj Rana, Shelley Randall, Vaikunt Ranganathan, Laurie Raymond, Madelyn Rayos, Kelly Real, Richard Remington, Anna Rhea, Catherine Rice, Harper Richardson, Stacy Riffle, Chris Rigby, Tracy Robertson, Beverly Robertson, Erin Roby, Ana Rocha, Casey Roche, Nicki Rodriguez, Bianca Rodriguez, Katherine Roeder, Laure Rogers, Daniela Rojas, Andrea Rondon, Jacob Rosewater, Hilary Rosselott, Katelyn Rossow, Payton Runyan, Nicole Russo, Tara Rutter, Elizabeth Ruzzo, Mahfuza Sabiha, Mustafa Sahin, Fatima Salem, Rebecca Sanchez, Muave Sanders, Tayler Sanderson, Sophie Sandhu, Katelyn Sanford, Susan Santangelo, Madeline Santulli, Alisha Sarakki, Marina Sarris, Dustin Sarver, Madeline Savage, Jessica Scherr, Abraham Schneider, Hoa Schneider, Abraham Schneider, Hayley Schools, Gregory Schoonover, Robert Schultz, Brian Schwanwede, Brady Schwind, Tanner Scott, Cheyanne Sebolt, Rebecca Shaffer, Neelay Shah, Swapnil Shah, Sana Shameen, Curry Sherard, Jonah Shifrin, Roman Shikov, Amelle Shillington, Mojeeb Shir, Amanda Shocklee, Clara Shrier, Lisa Shulman, Matt Siegel, Andrea Simon, Laura Simon, Emily Singer, Arushi Singh, Vini Singh, Devin Smalley, Kaitlin Smith, Chris Smith, Ashlyn Smith, Latha Soorya, Julia Soscia, Aubrie Soucy Diksha Srishyla Danielle Stamps, Laura Stchur, Morgan Steele, Alexandra Stephens, Dominique Stilletti Camilla Strathearn, Nicole Sussman, Amy Swanson, Megan Sweeney, Anthony Sziklay, Maira Tafolla, Jabeen Taiba, Nicole Takahashi, Sydney Terroso, Priyam Thind, Taylor Thomas, Hanna Thomas, Samantha Thompson, Jennifer Tjernagel, Jaimie Toroney, Ellyn Touchette, Laina Townsend, Madison Trog, Katherine Tsai, Angela Tseng, Paullani Tshering, Ivy Tso, Laura Tung. Samuel Turecki, Maria Valicenti-Mcdermott, Bonnie VanMetre, Candace VanWade, Alfonso Vargas-Cortes, Kerrigan Vargo, Dennis Vasquez Montes, Cristiana Vattuone, Jeremy Veenstra-Vanderweele, Alison Vehorn, Alan Jesus Benitez Velazquez, Mary Verdi, Brianna Vernoia, Michele Villalobos, Natalia Volfovsky, Jasmine Vongdara, Lakshmi Vrittamani, Allison Wainer, Jermel Wallace, Corrie Walston, Jiayaho Wang, Audrey Ward, Zachary Warren, Katherine Washington, Lucy Wasserberg, Grace Westerkamp, Casey White, Sabrina White, Casey White, Logan Wink, Fiona Winoto, Sarah Winters, Ericka Wodka, Aaron Wong, JessicaWright, Samantha Xavier, Sabrina Xiao, Simon Xu, Sidi Xu, Yi Yang, WhaJames Yang, Amy Yang, Meredith Yinger, Timothy Yu, Christopher Zaro, Hana Zaydens, Cindy Zha, Haicang Zhang, Haoquan Zhao, Allyson Zick, and Lauren Ziegelmayer Salmon.

Funding statement

There are no funders to report for this submission.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.