One of the most discouraging facts of racial inequality at the dawn of the twenty-first century in the United States is the disproportionate impact of crime, violence, arrest, and incarceration on African Americans and Latinos compared to whites. While 1 in 106 white men over age 18 was incarcerated in 2007, the figure for Latino men is 1 in 36, and for black men it is a staggering 1 in 15 (Pew Center on the States 2008: n.p.). At virtually any point in the justice system, blacks and Latinos are substantially overrepresented relative to their proportion of the population (Reference WalkerWalker et al. 1996). At the same time, blacks and Latinos also experience crime and violent victimization at far higher rates than whites. Overall homicide rates for blacks are more than seven times those for whites, and the homicide rate for black males ages 18–24 is more nine times that for whites of the same age (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2005). There is strong empirical evidence that both victims and incarcerated populations are heavily drawn from poor areas with high concentrations of racial minorities and that this concentration has serious consequences for children, families, marriage, neighborhood vitality, and economic opportunity (Reference ClearClear 2007). The promise of civil rights is the promise of inclusion; yet these vast disparities stand as stark reminders of the nation's long history of racist exclusionary practices.

How are we to make sense of these disparities half a century after Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965? The alarming data on minorities, crime, and victimization undermine claims of racial progress and threaten to limit or even reverse the movement toward greater racial equality. While we know much about how individual racial attitudes shape preferences and legal norms on crime and violence, and that developments in law and order have often traded on racial cues, we know much less about how America's racialized past continues to provide mechanisms for social policymaking and legal decisionmaking that perpetuate such deep inequities (see Reference Gilliam and IyengarGilliam & Iyengar 2000; Reference MendelbergMendelberg 1997; Reference MurakawaMurakawa 2005; Reference ProvineProvine 2007; Reference Wacquant and PrattWacquant 2005; Reference WeaverWeaver 2007).

I argue that no general account of race, inequality, crime, and punishment in the United States is complete without an understanding of the distinctive character of American federalism.Footnote 1 Federalism in the United States was forged in part as a mechanism for accommodating slavery, and it facilitated resistance to racial progress for blacks long after the Civil War (Reference DahlDahl 2003; Reference FinkelmanFinkelman 1981; Reference FrymerFrymer et al. 2006; Reference KatznelsonKatznelson 2005; Reference LiebermanLieberman 2005; Reference LowndesLowndes et al. 2008; Reference RikerRiker 1964). American federalism limits the authority and political incentives of the central government to address a wide range of social problems that give rise to crime and diffuses political power across multiple venues, which makes it difficult for the poor and low-resources groups to access decisionmaking. As a result, federalism renders largely invisible the only political terrain—urban areas—in which minority victims are routinely visible, as victims of both violence and political and economic marginalization. In order to address racial inequality in criminal justice, advocates for racial progress must overcome a dizzying array of fragmented lawmaking venues and commandeer the lawmaking powers of the central government, formidable tasks that have usually occurred when a confluence of exogenous factors, such as wars, social movements, shifts in demographics, economic catastrophe, or other calamities have come into play (see Reference Feeley and RubinFeeley & Rubin 2008 for a related discussion).

Conventional narratives of federalism and racial inequality in the United States typically focus on the problems of regional politics at the state and local levels and the successes of national political strategies in forcing these governments to accept more equitable legal standards and political outcomes. In contrast, the analysis of crime, law, and political mobilization presented here suggests that the limitations of American federalism run far deeper and are not confined to the parochialisms of regional politics. For much of the nation's history, American-style federalism has allowed the national government to escape pressure and responsibility for addressing inequality and stagnation in racial progress (see Reference RikerRiker 1964). Today, it continues to winnow debates about crime and justice in ways that undermine the political voice, representation, and empowerment of those most affected by crime and criminal justice—urban racial minorities. The effect of federalism on crime and punishment is to reinforce existing racially stratified access to power by: balkanizing mobilization efforts among urban minority groups that would otherwise be natural allies, diffusing political pressure about poverty across a wide range of political and legal venues, and limiting the scope and tenor of the central government's power to address social problems. The nature of the American federal system thus makes it difficult to see disparities in crime and punishment as linked to broader socioeconomic patterns of racialized policymaking, and the reframing of crime and punishment from local to national venues changes not only the participants involved but also the very nature of the problem itself, such that minority interests are at best obfuscated and, at worst, rendered invisible.

This article proceeds in four sections: I begin with a more detailed discussion of the features of American federalism that impose obstacles to the political voice of urban minorities for addressing crime and violence. Then, drawing on congressional hearings data, I investigate the interaction of federalism and group dynamics in national politics in order to understand how minority political mobilization and blacks as victims of long-standing racialized practices of exclusion are largely obscured. Third, I compare this to the political mobilization around crime and violence in two urban areas, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, to identify the primary players, problem definitions, and legal frames presented to lawmakers in these venues. While the two sites represent a small slice of the urban minority experience, they provide an illustration of the issues, politics, and political agitation that characterizes many urban centers (see Reference AndersonAnderson 1999; Reference CarrCarr et al. 2007; Reference GregoryGregory 1999; Reference LyonsLyons 1999). In this context, one finds a wide range of groups fighting their way into the political process, including citizens representing low-income, minority neighborhoods. I conclude with a discussion of how the nature of the American federal system makes it difficult to see disparities in crime, violence, and punishment as linked to broader socioeconomic patterns of racialized policymaking and how recognition of these features of the U.S. political system might promote productive political engagement on racial equality.

Federalism, Race, and Criminal Justice Disparities

One of the most common scholarly explanations for persistent racial inequities in crime, punishment, and criminal justice is that they represent a continuation of the long history of exclusionary practices in the United States beginning with slavery; continuing through the Jim Crow South, white flight, and race riots in northern ghettos; and culminating most recently in the prison state. Analysis of congressional drug policy, for example, illustrates how race and ethnic imagery have long been smuggled into drug policy debates and can be seen in contemporary discourse about crack cocaine and inner-city blacks (Reference ProvineProvine 2007; see also Reference MoroneMorone 2003). Others have drawn attention to the interaction between the civil rights movement, urban riots, moral panics, and exploitation of the law-and-order issue by political parties (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997, Reference FlammFlamm 2005; Reference MurakawaMurakawa 2005; Reference TonryTonry 1995, Reference Tonry2004; Reference WeaverWeaver 2007; see also Reference Wacquant and PrattWacquant 2005).

These approaches provide rich insight into national crime politics and serve as foundational analyses for understanding the persistence of racial inequalities in crime and punishment. There are, however, several reasons to expand the discussion beyond national politics and to flesh out more specifically the mechanisms through which racial hierarchies are perpetuated in crime and punishment. First, most citizens experience victimization in their neighborhoods and encounter police and the justice system at the local level. Local lawmakers face these realities, and the manner in which they respond to the people experiencing them deserves attention (Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1984). Congressional crime politics, by contrast, occupies a rather idiosyncratic political space because Congress has no need—and little constitutional mandate—to legislate run-of-the-mill criminal activity. Thus, very different political incentives and policy frameworks emerge at different levels of government with implications for the interests that are represented and the way issues are framed.

A second reason for expanding analysis beyond national politics is that there are enormous differences in victimization across racial groups. While African American and Latino young males experience the long arm of the law in unprecedented numbers, they are also victims of violence in numbers that far outpace any other demographic group, and overall declines in violent crime in recent years have been far less significant in minority communities than in whiter, more affluent areas (Reference ThacherThacher 2004). Any discussion of the racialized nature of crime and punishment in the United States, then, must take account of the day-to-day violence that inheres in many black and Latino neighborhoods and the political mobilization of these communities for greater public safety. While scholars have been attentive to the role that primarily white victims' groups have played in the politics of crime and punishment, they have far less to say about the political agitation by groups representing minority victims (see Reference BarkerBarker 2006; Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2006; Reference ZimringZimring et al. 2001). As this article demonstrates, people living in high-crime areas often place enormous demands on local elected officials and police departments to do more to keep citizens safe, including pressuring the police for more patrols and more arrests, along with improvements in schools, recreational opportunities for youth, and reducing urban blight (Reference CarrCarr et al. 2007; Reference LyonsLyons 1999; Reference MillerMiller 2008). That these demands often translate into little more than top-down, aggressive policing activities may reveal as much about the interaction of federalism and racialized group interests in the United States as it does about the racial attitudes of local officials or support for law-and-order punishment practices among the American public.

In contrast to extant approaches, then, I consider racial inequality in modern crime politics at the foundations of American political institutions. For this reason, I compare here the political representation and framing of crime and punishment at the national level, on which much of our understanding of race, punishment, and inequality is based and where researchers often expect solutions to emerge, to that of local politics, where Blacks and Latinos experience the daily inequities of victimization and involvement with the justice system and where minority political and legal interests are most visible. Of course, most criminal law and criminal punishment is meted out in state legislatures and courts, but the goal of this article is twofold: first, to illustrate the asymmetric distribution of power and interests under our constitutional design between the locale where minorities experience crime, victimization, and punishment and the national venue that is expected to ameliorate these realities; and second, to give voice to the largely invisible efforts of minority activists pressuring lawmakers to address the social conditions that give rise to crime and violence (see Reference MillerMiller 2008 for a detailed comparison with state politics). This requires a detailed analysis of the capacity of the central government to address these problems and the problem definitions and legal narratives about crime, violence, and victimization that are visible in urban, minority communities. This approach reveals not just differential access to power but differential institutional capacities across the varied and complex landscape of American federalism. Thus, this article does not address specific policy outcomes per se but, rather, reveals why particular problem definitions, policy frames, and legal narratives about crime, victimization, and punishment are more likely in some venues than others. This can aid scholarly understanding of how racial hierarchies can be perpetuated in the absence of formal legal discrimination or when discriminatory attitudes are mitigated. As Lieberman notes, “Racial bias in a race-laden policy need not be the result of racism per se. It may instead result from institutions that mobilize and perpetuate racial bias in a society and its politics, even in institutions that appear to be racially neutral” (Reference LiebermanLieberman 1998:7). I suggest here that racial inequities in crime, punishment, and victimization have at least some of their roots in the racialized access to power at the foundation of the U.S. constitutional system.

Federalism and Its Limitations for Progressive Social Action on Crime

Several features of the federal structure put into place at the Constitutional Convention have had enduring effects on the political and legal struggle for racial equality (Reference FinkelmanFinkelman 1981; Reference LiebermanLieberman 1998; Reference RikerRiker 1964). First, the division of power between the states and the new national government left intact virtually of all the states' traditional police powers—powers used to address a wide range of citizen concerns, including the health, safety, and morals of the state's citizens. This choice was an obvious one, as the territorial and geographic allegiances to the colonies pre-dated the American Revolution, but leaving these powers in the hands of the states also allowed the new nation to avoid conflict over the most important jurisdictional issue of the day: human bondage (see Reference DerthickDerthick 1992; Reference MadisonMadison et al. 1987). Most critiques of American federalism focus on how this allowed recalcitrant states and localities to block racial progress (Reference FinkelmanFinkelman 1981; Reference FrymerFrymer et al. 2006; Reference GraberGraber 2006; Reference LiebermanLieberman 1998; Reference RikerRiker 1964). The strength of state governments under the U.S. Constitution provided pro-slavery advocates with powerful legal and political claims to maintaining their “peculiar institution” and, as Frymer et al. note in their discussion of Hurricane Katrina, continues to “provide opponents of civil rights with a powerful, legitimate, and seemingly ‘race-neutral’ narrative through which to stymie progress on this front” (Reference Frymer2006:48; see also Reference GraberGraber 2006). Such assessments suggest that the problem of federalism for racial progress is that the progressive possibilities at the national level are all too often diluted at lower levels of government (Reference LiebermanLieberman 1998).

Two other features of the distinctive American system, however, serve as equally significant barriers to addressing racial inequalities in crime and punishment. The first is the relatively anemic nature of congressional power (Reference Esping-AndersonEsping-Anderson 1990; Reference FrymerFrymer et al. 2006; Reference KincaidKincaid 1999; see also Reference Tocquevillede Tocqueville 2004). Limited by design, Congress has a narrower jurisdictional breadth than state governments with respect to addressing major social policy issues. Certainly, congressional power has grown over the course of the nation's history, and when a national consensus emerges, constitutional divisions of power are frequently glossed over in favor of national authority (Reference Feeley and RubinFeeley & Rubin 2008). Lacking a clear, decisive national consensus, however, congressional authority is inhibited by the fact that it lacks a constitutional mandate to legislate on broad social welfare issues. While the federal courts have given Congress a wide berth in its exercise of the Commerce Clause powers since the New Deal, the Supreme Court does occasionally limit the scope of Congress's power based on its reading of the Commerce Clause in Article I, Section 8 and the Tenth Amendment and continues to hear cases challenging congressional authority to address major social policy domains.Footnote 2 While these challenges are rarely sustained, they can provide sufficient opposition to fracture fragile coalitions or cause them to lose momentum (Reference DinanDinan 2002). The recent constitutional challenges by 14 state Attorneys General to the congressional health care bill represent the most recent example of this long and storied history.Footnote 3

More important, the fact that Congress has expanded the reach of its domestic policymaking does not alter the fact that most social policy that affects the day–to-day lives of citizens—public safety, education, transportation, public works, and health care, for example—is often enacted by state and local governments. As a result, Congress not only has an episodic mandate to address a great many social issues that affect rates of criminal offending and victimization, but it also has few political incentives to address these thorny issues. Put in stark terms, the U.S. government does not have clear constitutional responsibility and accountability for legislating on the health, safety, and social welfare needs of the polity as a whole. When Congress does legislate on broad social issues—public safety, social welfare, education, or the environment, for example—it often does so by shoehorning policy into Article I, Section 8, or relying on enabling legislation from constitutional amendments. While these strategies are often sufficient in the context of broad national consensus, they represent weak grounds for the kind of policy that is demanded by vast and deep inequalities across racial groups. Even on economic issues, where Congress's authority is clearer, national lawmakers are frequently asked to justify the ability of Congress to trump state power in this realm.Footnote 4

A second distinctive feature of American federalism that has implications for understanding racial inequality in crime and punishment is the multiple legal and legislative venues for participation. This porousness can provide citizens with multiple locations for participation (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner & Jones 2002; Reference PrallePralle 2006). However, multiple centers of power also make it difficult for the poor and low-resources groups to sustain pressure across a political landscape that is navigable largely through sustained human, social, and fiscal capital. Multiple venues can reinforce and exacerbate classic collective action problems, which disproportionately disadvantage the poor and racial minorities (Reference Brooks and ManzaBrooks & Manza 2007; Reference MillerMiller 2007). Social movement scholars have long recognized the importance of a group's capacity to mobilize resources in order to successfully function as a pressure group (Reference McCarthy, Zald, Buechler and CylkeMcCarthy & Zald 1987). These resources need not be financial but can include significant numbers of highly motivated, preference-intense people, and/or a public image that is highly favorable (see Reference Fiorina, Skocpol and FiorinaFiorina 1999; Reference Schneider and IngramSchneider & Ingram 1993). Coupled with fiscal resources, these forms of capital can help launch a narrowly focused interest group into a wide range of political and legal venues, while others—with less financial support, more diffuse supporters, or a less positive public image—struggle to maintain pressure at just one legislative locale. Thus, federalism is an important element in understanding racial inequality not only because of the space it has allowed states in blocking reform but also because of the limitations it imposes on the power of the national government to ameliorate the conditions giving rise to crime and violence and the obstacles it erects to collective action efforts of poorly resourced groups.

Race, Crime, and National Politics

In sheer relative terms, the federal government's involvement in crime fighting today is dramatically greater than such activity in the nineteenth century, and the range of crime issues that the federal government addresses leaves very few crimes that are not prosecutable under both national and state laws. Federal crime fighting, however—through congressional legislation, executive agencies, and federal courts—remains a selective endeavor with a great deal of discretionary decisionmaking and cherry-picking of crimes and cases by federal agencies and federal criminal courts. This fundamental aspect of U.S. federalism means not only that the vast majority of social control efforts happen in state and local contexts but, equally as important, that the national government's jurisdiction over crime is fluid, waxing and waning depending on broader social and political contexts.

As a result of the deferential orientation of the original Constitution to state police powers, congressional activity around the criminal law has evolved piecemeal as jurisdictional terrain between states and the national government has shifted over the course of U.S. history, particularly in the wake of massive external shocks.Footnote 5 Following the Civil War, for example, concerns about fraud and corruption, labor strife, and electoral violence dominated the national legislative agenda; later, technological changes, such as the invention of the automobile and telecommunications, pushed interstate transportation of stolen goods and mail fraud to the fore. Kidnapping, motor vehicle theft, fraud, and corruption came onto the congressional agenda in the early decades of the twentieth century as well and in the aftermath of World War II, social upheavals and rising crime rates, juvenile delinquency, drug abuse, and urban riots all gained congressional attention (Reference FriedmanFriedman 1993; Reference MillerMiller 2008). Law-and-order concerns grew dramatically in the 1950s and continued well into the 1980s (see Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2006; Reference MillerMiller 2004, Reference Miller2008; Reference MurakawaMurakawa 2005; Reference WeaverWeaver 2007; see also Reference McCann, Johnson, Sarat and OgletreeMcCann & Johnson 2009 for a discussion of this history with a focus on the death penalty).

Congress's attention to crime, then, has long been episodic and fragmented with little connection to the socioeconomic inequalities that contribute to disparate rates of criminal offending and differential interaction with the justice system. As Reference ScheingoldScheingold (1984) notes, crime at the national level is susceptible to authoritative but largely symbolic attention as lawmakers are less accountable for outcomes than they are at the local level. Attention to crime waxes and wanes as members of Congress react to high-profile crime events that often have little to do with the day-to-day realities of crime victimization and even less connection to the race and class stratifications that may contribute to them. This process often reflects and reinforces dominant race and class hierarchies. The Mann Act, for example, prohibiting “white slavery,” was passed in 1910 in the context of anxieties about ethnic immigrants, while the Lindbergh Act was enacted in 1932 in response to the kidnapping and murder of Charles and Anne Lindbergh's baby—an early example of the kind of rare, high-profile crime that draws in public attention and demands legislative attention. The result of this open-ended jurisdiction on crime is that national crime debates have been influenced by a variety of political developments that themselves often have roots in racialized attitudes and racially stratified access to power.

The Narrow Scope of Congressional Attention to Crime

In order to more fully assess the nature of congressional attention to crime, I compiled data from the Policy Agendas Project, which includes all congressional hearings from 1947 through 2006.Footnote 6 The data in this section draw on congressional hearings from the Crime, Law and Family category (with hearings on family issues that were not crime-related excluded) between 1971 and 2000, which constitutes 2,180 crime hearings. In addition to these data, I took a sample of these hearings in order to collect and code data on witnesses, resulting in a second dataset of 444 hearings. Witnesses were coded into five general categories: criminal justice agencies, government representatives, professional groups, citizen groups, and other/unknown groups. Witness representation at legislative hearings provided insights into the groups that have access to lawmakers in that venue, as well as the groups that lawmakers believe to be active and important (see Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner & Jones 2002). Details of the data, sample selection, and specific categories are outlined in the Appendix.

Figure 1 illustrates the shifting congressional attention to five substantive crime topics—police/prisons/firearms, drugs, crimes against women and children, white collar crime, and juvenile justice—and also provides some context for congressional attention to these issues. Not surprisingly, in the 1970s, while civil protests flared, prison riots were in the news, and civil rights activists drew attention to police brutality, Congress gave substantial attention to issues involving police and prisons. For the first half of the 1970s, about a fifth of all the crime hearings in Congress addressed these issues. The Attica prison riot captured national media attention in 1971 and, along with a series of other violent incidents in the nation's prisons, contributed to dozens of hearings on the conditions of confinement, the shortcomings of the nation's prisons, and efforts to improve the treatment and rehabilitation of prisoners.Footnote 7 Similarly, there was substantial attention to regulating firearms, reflecting the political pressures and opportunities presented by urban riots, violent crime, and assassinations of public figures in the 1960s. Sixty-four percent (32/50) of congressional hearings on police/firearms during the 1970s addressed some form of weapons control.Footnote 8

Figure 1. Congressional Hearings on Crime and Justice, 1971–2000.

Less than 10 percent of all hearings during the 1970s involved drugs, but by the 1980s, when national attention migrated from antiwar activities, urban race conflicts, and the political violence of previous decades, the drug issue exploded onto the national agenda. Violent crime rates were still high, and illegal drugs became a focal point of the Reagan administration's domestic policy agenda (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997). First Lady Nancy Reagan initiated a “Just Say No” campaign, and high-profile media attention to drug violence and deaths all contributed to the dramatic rise in congressional attention to drugs in the 1980s and 1990s. Whatever the motivations of the Reagan administration for its attention to drugs, Congress's focus was largely on international drug trafficking and money laundering. Nearly half of all congressional hearings on drugs during the Reagan years (1981–1988) were about these topics (90/208).

Crimes against women and children, largely unaddressed in previous decades, gained traction in Congress in the late 1970s and continued a slow but steady growth through subsequent years. Juvenile justice issues received less attention than others in this 30-year period, but historically juvenile delinquency concerns have also experienced periods of rapid growth in attention, particularly during the 1940s and 1950s when concerns about absent fathers and juvenile deviance were at their peak (see Reference BernardBernard 1992).

This episodic and somewhat idiosyncratic attention to crime is consistent with the fluid and shifting nature of congressional jurisdiction on crime. Crime concerns come and go, and sustaining attention to any single problem over the long term is difficult as new issues and events push new priorities ahead. This makes it especially unlikely that Congress will sustain attention to racial inequities. Indeed, a number of scholars have concluded that, when issues of racial inequity did arise, the incentives favored emphasizing them rather than mitigating them, particularly as narrow law-and-order arguments were used to implicate Blacks in riots and other undesirable activities and to undermine civil rights claims (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997; Reference FlammFlamm 2005; Reference MurakawaMurakawa 2005; Reference WeaverWeaver 2007).

One of the consequences of this episodic nature of crime on the congressional agenda is that attention tends to cluster around high-profile issues and events and to be decoupled from larger, ongoing social policy concerns. To some extent, this is a result of the fact that Congress's clearest jurisdiction on crime issues is oversight of federal agencies, financial institutions, border control, and cross-state law enforcement, not a broad mandate to address social problems. Most crime hearings take place in the Senate or House Judiciary Committees or Special Narcotics committees, and hearings are generally not held in conjunction with other committees (only 89 hearings [4 percent] between 1971 and 2000 were held jointly with another committee). While the standard crime committees have a broad mandate, they rarely intersect with other committees that deal with the social and economic environments that create criminogenic conditions. Beyond the primary committees of Judiciary and Narcotics, the other major committees holding crime hearings are Government Operations and Foreign Affairs. Table 1 illustrates committees that held hearings on crime topics that might involve concerns about racial inequality over the 30-year period: drugs, juveniles, riots and crime prevention, and police/prisons.

Table 1. Committees Holding Hearings on Crime and Justice, 1971–2000

* Other committees holding drug hearings include: House Armed Services, House Energy and Commerce, House and Senate Expenditures in Executive Departments.

For riots and crime prevention issues, the Select Committee on Aging held hearings almost exclusively on crimes against the elderly, clearly not a focus on racial inequalities. More than three-quarters of drug hearings were held in Judiciary, Select Narcotics, Foreign Affairs, or Government Reform/Oversight committees, also not committees likely to address underlying causes of crime. For juveniles, the major non-Judiciary committee is the House Education and Labor/Workforce Committee. This appears to be the one issue area where Congress connects crime to broader social problems. Thirty-eight percent of juvenile delinquency/justice hearings are held in this committee. However, juvenile issues come and go from the congressional agenda, rarely address inequities across race and class, and only infrequently result in legislation focusing on improving the living conditions of youth. Other than these, few hearings were held in any committee that might have the authority to craft legislation addressing the larger social problems of inequality that contribute to inequities in the justice system.

Congressional attention to crime is also dominated by “state-of-the-problem” hearings with no proposed legislation, program, or activity at stake. Across the same four substantive crime categories (drugs, juveniles, police/weapons, and riots/crime prevention) and over 967 hearings, only 21 percent considered new legislation, and a microscopic 2 percent considered new programs or agencies.Footnote 9 Only 14 percent (30/208) of all drug hearings held during the Reagan administration were addressing any proposed legislation. Two juvenile justice hearings considered new programs for juvenile delinquency prevention and runaway youth, and another considered an act that would consolidate youth programs into block grants.Footnote 10 Three police/prison hearings and two riots/crime prevention hearings considered programs, but none of these hearings addressed racial inequality in any manner or were designed to address the relationship between crime and other problems of inequity in resources, neighborhoods, or living conditions.

The lack of coordination with committees that could connect crime to a wide array of other social problems facing low-income minorities and the limited attention to actual laws and programmatic solutions illustrate the relatively easy decoupling of these issues at the national level. Given Congress's clear jurisdictional control over supply-side agencies, policies, and resources in the “drug war,” for example, such as the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), U.S. Customs, and the Department of the Treasury, it is not surprising that so much attention is dedicated to interdiction and aggressive law enforcement. The same can be said for gun violence and riots. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; the FBI, and U.S. Attorneys' offices are natural constituents and allies, not to mention agencies over which Congress exercises some oversight. Responsibility for educational, health, economic, or other social reform that may intersect with crime and justice problems is scattered across a wider range of legislative and legal venues and thus poses institutional obstacles to policymaking that connects crime to these larger social problems.

Voice and Representation in Congress

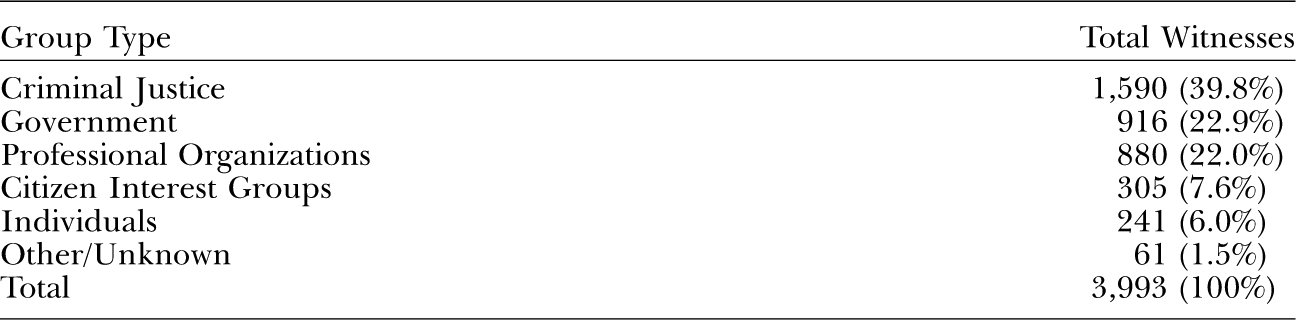

The second and related problem of congressional attention to crime, justice, and inequality is also a function of a distinctive aspect of American federalism, which divides jurisdictional authority across multiple legislative venues. One can thus observe what types of issues, interests, and problem frames are represented in national politics and compare them to local crime politics. In this section, I analyze witnesses across a sample of congressional crime hearings between 1971 and 2000. Table 2 illustrates the array of 3,993 witnesses who appeared before Congress across a sample of 431 crime hearings during this time period.

Table 2. Witnesses at Congressional Hearings on Crime and Justice, 1971–2000

Criminal justice agencies—police, prosecutors, judges, and corrections officials—represent a stunning 40 percent of these witnesses. Criminal justice agencies certainly have a role to play in defining crime problems, but their professional interests narrow problem definitions and the range of solutions they propose and support.Footnote 11 Law enforcement agencies alone represent 18 percent (707) of all witnesses.

Some dominance of criminal justice agencies has to do with the fact that Congress holds oversight hearings on federal criminal justice agencies. However, even outside of these hearings, criminal justice agents constitute a regular and sustained component of the witnesses. Several measures of the strength of criminal justice agencies as experts illustrate this point. First, an examination of only those hearings (n=294) in which no bill was under consideration and that did not involve oversight of any federal agency, program, or executive action (termed “state-of-the-problem” hearings) reveals a strikingly similar distribution of witnesses. As Table 3 illustrates, criminal justice agencies still constituted two in five witnesses (43.0 percent). A second approach, also illustrated in Table 3, was to examine only hearings on substantive crime topics, such as drugs, riots, crime prevention, juveniles, crimes against women and children, and white collar crime (n=215) and exclude hearings on the federal courts, the executive branch, law enforcement agencies, or federal prisons where one would expect to find a high percentage of representatives from the criminal justice system. At these substantive hearings, however, criminal justice agencies still represented 38 percent of all the witnesses (769/2,047). The largest criminal justice group to testify was law enforcement officers and agencies, constituting 21 percent (426/2,047) of all witnesses. Drug hearings alone involved testimony from almost 500 criminal justice agents, which represented 45 percent of all the witnesses who testified at drug hearings. In fact, many of the government witnesses who were not from criminal justice agencies also represented organizations involved in investigations and prosecutions, such as the Treasury Department, so in practice, the perspectives of those with responsibility for investigating, prosecuting, and confining probably constitute more than half of all perspectives brought to bear on drug issues in Congress.

Table 3. Witnesses in State-of-the-Problem and Substantive Crime Hearings, 1971–2000

Congressional crime hearings often include lengthy testimony from criminal justice agencies detailing their work. In one typical example, a spokesman for the DEA provided an accounting of recent activities at a 1996 hearing on drug trafficking in California:

Counterdrug operations during the 1990s successfully dismantled massive conversion labs in Bolivia and Peru, forcing the traffickers to abandon these large operations in favor of small, more mobile laboratories in remote locations. Also, law enforcement efforts took aim at the air transportation bridge, which was a trafficker's preferred method of transporting cocaine base from the mountainous jungles of Bolivia and Peru to the cartel operations in Colombia. This resulted in the traffickers having to abandon their air routes and resort to riskier transportation over land and water

(Hearing before the subcommittee on National Security, International Relations and Criminal Justice of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight. House of Representatives, 23 Sept. 1996, Y4.G74/7:R29/19. 98-H401-52).While criminal justice agencies were heavily represented across a wide range of hearings, there was a glaring gap in the witnesses from citizen groups who represented people living with crime on a regular basis. In the full analysis (Table 2), a paltry 7.6 percent of all witnesses were from any type of citizen group, and almost a third of all citizen group witnesses were on one side or the other of the gun debate or represented the ACLU (97/305, 32 percent). By contrast, the NAACP, representing the largest and most widely recognized civil rights organization in the country, appeared at merely 12 of the 431 hearings over the 30-year period.Footnote 12 Other groups that might represent the interests of racial minorities appeared sporadically, such as the Congress of Racial Equality, Operation PUSH/Rainbow Coalition, the Urban League, or El Pueblo Unido, but all together these groups constituted a virtually invisible one-half of 1 percent of all witnesses (28/3,993).

When I examined just state-of-the-problem hearings (Table 3)—those hearings in which these groups might have the greatest voice—the picture was even more grim. Here, citizen group witnesses represented just barely 6 percent (152) of all the witnesses. Again, most of these groups represented citizens with a single-issue focus (such as gun advocates or opponents), and those with a broader scope are more likely to represent the interests of the elderly (such as the American Association of Retired Persons) than the interests of racial minorities. A few groups, such as the Children's Defense Fund and the American Friends Service Committee, have broad mandates that include the interests of low-income and minority groups; and a tiny handful of neighborhood organizations, such as United Neighborhood Organization or the Citizens' League of Greater Youngstown, appeared on rare occasions.Footnote 13 As the next section illustrates, many of these groups bring a perspective on crime and punishment that is deeply rooted in the lived urban experience of the crisis in education, unemployment, drug addiction, weak public infrastructure, and a host of negative social conditions. Their presence in Congress, however, borders on the nonexistent.

Congressional drug hearings, in particular, are notable for their lack of voice from people actually experiencing drug crime or drug addiction, particularly in the inner cities. As noted earlier, in some respects this is not surprising, given Congress's clear jurisdiction over borders and interstate transportation of illegal substances. Nonetheless, the dominance of testimony from law enforcement was particularly glaring give the complexity of the drug problem. Groups representing citizen interests of any kind were just 3 percent of witnesses at drug hearings (35/1,060), and groups that move beyond single issues and are likely to connect drugs to a wider range of social pathologies were almost entirely absent (8/1,060). Testimony from individuals unaffiliated with any group—which would include victims of drug crime, former drug addicts, and former gang members, as well as any other unaffiliated individuals—represented barely 3 percent (40/1,060) of witnesses.

Congress's narrow focus on interdiction and local law enforcement is illustrated in a 1995 hearing on drugs that included the predictable array of DEA representatives, Customs officers, and U.S. Department of Defense drug enforcement officials (97-H401-8). The hearing spanned two days, and though witnesses and lawmakers alike repeatedly referred to illegal drugs as a major social problem, the testimony and discussion focused almost exclusively on supply-side strategies. This emphasis is especially striking in light of the fact that four high school students from the District of Columbia were invited to testify, and their testimony migrated to other issues, such as poverty, health care, and jobs. One student, for example offered this testimony:

Illegal drugs are destroying my community. Many families are suffering because their parents, their children are using illegal drugs. I have a friend whose father is using drugs and this father spends all the family money on drugs. That's why he [friend] quit school…. Last summer, I was attacked by three drug dealers. I was unconscious for six hours. My family worries so much. They worry for my life. All the while they fear for the hospital bills because we didn't have the insurance

(“Illicit Drug Availability: Are Interdiction Efforts Hampered by a Lack of Agency Resources?” Hearing, 97-H401-8, 1995, p. 16).Lawmakers did not respond to these larger social problems, focusing instead on a demonstration by drug-sniffing dogs and “just say no” strategies.

The case of gun control also serves as an excellent example of how the peculiarities of U.S. federalism perpetuate racially skewed access to the establishment and enforcement of legal rules. Gun rights activists have been particularly successful in exploiting the multiple legislative venues of American federalism to win legislative and legal victories (see Reference GossGoss 2006) and represented over one quarter of the citizen witnesses (19/67) at hearings on firearms and weapons. Groups such as the National Rifle Association (NRA) have a clear presence, but so do organizations such as Citizens Committee to Keep and Bear Arms; Gun Owners of America; and statewide gun rights organizations, such as the Coalition of New Jersey Sportsmen, as well as gun manufacturers and gun shop owners. At a 1993 congressional hearing on a bill that would prohibit possession of a handgun by a juvenile, a representative from the NRA raised federalism concerns directly:

We do have one major concern with the proposed legislation and that is our understanding in reading the bill is we believe that it would intentionally or otherwise directly involve the Federal Government in an area of criminal justice which has traditionally been left to State judicial systems. I am speaking specifically to the issue of criminalizing certain acts of juveniles

(Hearing before the Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary Senate. 94-S521-6, 13 Sept., 1993).He went on to suggest that sweeping national legislation that imposes uniform laws across the states is inconsistent not only with the structure of lawmaking authority under federalism but also with the nature of the problem.

The statistics on violent behavior may partially include every race and income group, but the overwhelming disproportionate impact on poor black and Hispanic inner-city children is where the problem lies. Solutions must be tailored accordingly and not be sweeping or symbolic. The pathologies of the inner city cannot be remedied by creating stronger [gun] laws

(Hearing before the Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary. Senate, 1994, S521-6, p. 69).This is particularly interesting, given that the NRA made virtually the opposite argument—that uniformity is a necessity—when opposing Philadelphia's and Pittsburgh's efforts to impose stricter gun control legislation precisely because of the unique contexts for racial minorities that occur in those cities (see Reference MillerMiller 2008). While this is an excellent illustration of the NRA's mastery of American federalism, it also reveals the real limitations on congressional power. It is with no small irony that one reads the NRA representative's comments, knowing that the remedies for “pathologies of the inner city” are on the margins of the lawmaking powers of the central government.

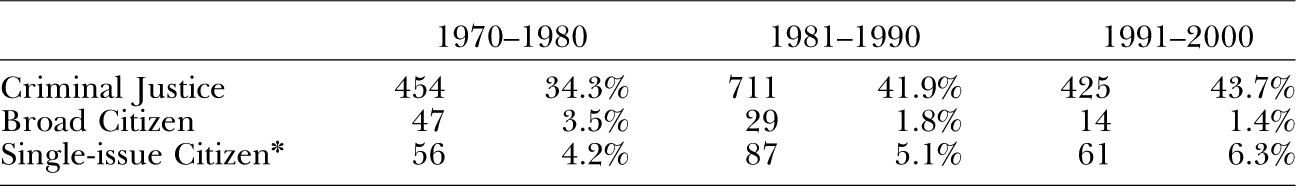

What keeps groups representing minority crime victims from greater visibility in congressional crime debates? Table 4 compares criminal justice witnesses to citizen witnesses by decades and illustrates the fact that more witnesses representing citizen groups with broad concerns appeared during the 1970s, when riots, gun violence, prison, and police issues were on the congressional agenda more than at any other time period.

Table 4. Criminal Justice and Citizen Group Representation by Time Period

* Includes victims and civil liberties groups.

This finding is particularly important because much of the extant scholarship about racial inequality, crime, and punishment centers around national processes that led lawmakers to disavow racial progress and promote crime control as a mechanism for maintaining racial hierarchy during the 1960s and 1970s (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997). Many also see this era as an important break with a more rehabilitative past that emphasized reintegration, in contrast with a more managerial model of crime control that exists today (Reference GarlandGarland 2001; Reference SimonSimon 2006). However, broad citizen groups most likely to call attention to racial inequities and frame crime problems in terms of rehabilitative potentials—including the NAACP, the Urban League, the National Urban Coalition, Operation PUSH, El Pueblo Unido, and the National Center for Urban and Ethnic Affairs—all appeared more frequently in the 1970s than in any other decade under examination here. This suggests that while the issues of the day (urban riots, prison and police upheavals, gun violence, and civil rights protests) may have provided opportunities for lawmakers to exploit law and order fears as a proxy for animosity toward blacks, and/or to back off from prior commitments to rehabilitative ideals, they also provided an opportunity for crime issues to be connected to broader social problems of racial inequality. In other words, the same forces that drove crime onto the political agenda as an opportunity for retrenchment and racial backlash also opened up possibilities for framing crime as part of a larger civil rights program. As this political moment passed, however, the process reverted to its default state and the normal routines of congressional attention to crime returned, decoupling the issue from other problems and responding to the latest crime issue.

The absence of neighborhood, community, grassroots citizen organizations representing the urban core in general, but particularly after the 1970s, is glaring. One explanation is that these groups are effectively represented by the larger, national organizations such as the NAACP and the Congress on Racial Equality. Another is that they are choosing to opt out of that political venue. There are several reasons to be skeptical of both of these explanations. First, as we have seen, these national groups appeared at a tiny fraction of hearings analyzed, so the voice of urban minorities, even if it were represented in those groups, would still be extremely small. The limited presence of these national groups is somewhat of a puzzle. They are clearly not resource-poor, and they have demonstrated their willingness and capacity to fight political battles in a wide range of legislative and legal venues. Some have suggested that the national civil rights organizations became reluctant to address inequities in criminal punishment as these issues came to be associated with rising crime rates and urban violence (Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2006), and ethnographic research on urban black neighborhoods provides some support for the idea that strains of class division run deep on issues of crime and violence (Reference AndersonAnderson 1999). Others have demonstrated that most national interest groups do not effectively represent the most disadvantaged (Reference StrolovitchStrolovitch 2006). Equally as important, however, there are very few hearings that address crime in broader contexts of neighborhood conditions, thus providing few opportunities for civil rights groups to appear, even if they want to.

In sum, these twin aspects of federalism—the limited scope of congressional authority over social problems and the uneven access of groups—have implications for which crime issues gain attention, how those issues are framed at the national level, and how racial attitudes and discriminatory practices are magnified in law-and-order politics. There are powerful institutional incentives in Congress to confine crime and punishment to narrow law-and-order frameworks, and this is not difficult to do, given the episodic nature of crime on the congressional agenda and the types of issue frames that single-issue groups and criminal justice agencies bring to bear on the legislative process. In addition, Congress rarely hears from groups representing black and Latino victims, people living with high rates of crime victimization in their community, or citizens experiencing the collateral consequences of mass incarceration and some of the worst living conditions in the United States. This environment is ripe for legal frameworks around crime and punishment that emphasize individualistic conceptions of criminal behavior and disconnect crime from broader social and economic processes, rendering largely invisible so many black victims. American federalism facilitates this truncated process by limiting Congress's social welfare-making powers and spreading jurisdictional control over quality-of-life issues across multiple legislative venues.

Local Crime Politics: Political Mobilization of Urban Minorities

It would be a mistake to see urban politics as a potential venue for minority political mobilization without recognizing the long history of exclusion, racial prejudice, and often violent opposition to minority political empowerment in these settings. Indeed, one of the reasons for a national civil rights strategy was the repeated, failed attempts in state and local governments to address racial inequities and, in particular, to protect blacks from the stranglehold on local politics held by white supremacists. Equally as damning to the local context was the eruption in many northern, urban areas of anti-integrationist violence during and after the civil rights era.

But the parochial, exclusionary nature of local politics must be balanced against the likelihood that such exclusion is equally bad or worse at other levels of government. As illustrated by the previous section, the incentives at the national level favor responding to narrow law-and-order concerns driven by high-profile issues of the day that are far removed from broader social problems. In contrast, local urban crime politics is contentious and pluralistic, far better representing minority interests generally and the interests of black crime victims specifically.

In this section, I explore political mobilization around crime and violence in two urban areas, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, through the analysis of 500 witnesses and their testimonies at 45 city council hearings, and 17 interviews with local lawmakers in these two cities. I coded witnesses according to their group affiliation in the same manner as the witnesses at congressional hearings. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh represent important venues for this analysis for two reasons. First, they are localities where crime and violence have been issues of central concern to residents. Both cities have relatively high crime rates and high rates of victimization for blacks. Indeed, the state of Pennsylvania has one of the highest black homicide rates in the country, with Philadelphia and Pittsburgh being the primary source of those homicides (Violence Policy Center 2010). Second, these cities represent areas with substantial African American populations, providing an opportunity to observe political mobilization on crime issues at the grassroots level, without the winnowing and filtering that takes place in national politics. During most of the time frame of this study (late 1990s through 2006), Philadelphia had an African American mayor (John F. Street) and seven black city council members (41 percent of the city council). Pittsburgh had two black city council members (22 percent of the city council). Details on the compilation of hearings, interviews, and site selection are in the Appendix.

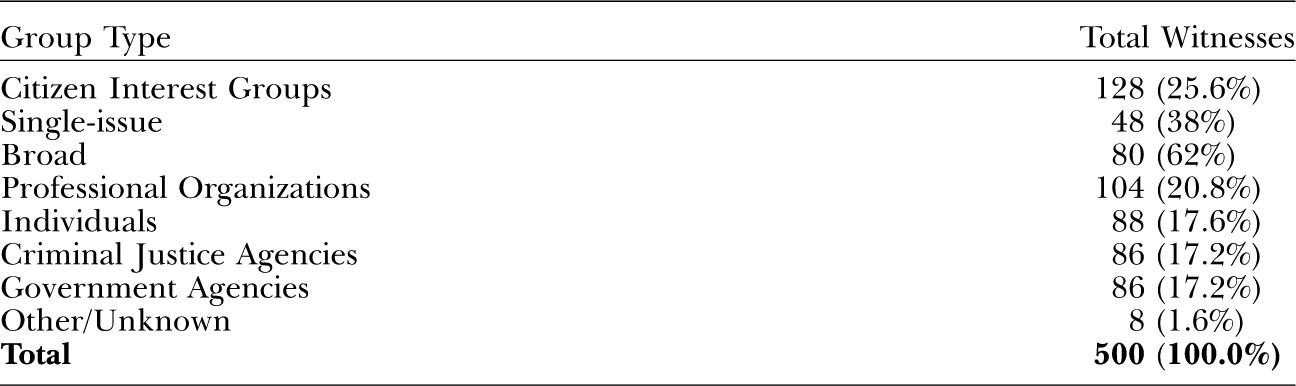

Table 5 illustrates the breakdown of group representation in these cities on a wide range of crime issues across the crime hearings between 1997 and 2006. What is striking is the strength of citizen groups. Fully 25 percent of the witnesses (128/500) at local crime hearings over the nine-year period came from citizen organizations, nearly four times as many as in Congress over a period one-third as long.Footnote 14 Furthermore, the presence of citizen groups was almost a mirror image of the representation of criminal justice agencies in Congress. Where police, prosecutors, judges, corrections officials, and other agents of the criminal justice system were the modal witnesses at congressional crime hearings, citizen groups representing broad concerns about a wide range of social issues were the most frequent in these two cities. In addition, while citizen groups were a small fraction of congressional witnesses, police and prosecutors were only modestly represented in local urban crime debates. Here we can contrast the ease with which law enforcement and prosecutors are drawn into Congress's jurisdiction over border control, guns, and weaponry with the diffuse and varied control over these agencies at the local level.

Table 5. Witnesses at Urban Crime Hearings, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, 1997–2006

Not only did citizen groups represent the modal group generally, but the dominant type of citizen group involved in local crime politics was not a single-issue group but, rather, a broad one, addressing crime in the context of a wide range of social problems. One hundred and thirty-one citizen groups participated in local crime politics during this time period, and 102 of them (78 percent) were broad organizations whose missions extended well beyond crime and justice to other quality-of-life issues such as neighborhood conditions, schools, recreational and employment opportunities, and so on. By contrast, during a comparable period in Congress, only 11 such broad citizen groups appeared over seven years, across twice as many hearing opportunities (103). Stated differently, local elected officials heard from an average of two and a half citizen groups with broad quality-of-life concerns each time they held a crime and justice hearing. Congress heard from just one such group every 10 hearings. In addition, while citizen groups in Congress are overwhelmingly single-issue in nature, at the local level of participation, citizen groups with broad concerns outnumbered single-issue groups by almost three to one.

Many of these citizen groups represent low-income and minority neighborhoods; these groups are not only central to discussions of crime and justice, they are also important constituents for local politicians (see Reference BerryBerry et al. 2006 and Reference StrolovitchStrolovitch 2007 for discussion of race and class bias in interest group activity). For example, in September 2007, during the Philadelphia mayoral race, candidate Michael Nutter met with members of the group Strawberry Mansion Community Concerns (SMCC) to clean up local city streets.Footnote 15 According to the 2000 U.S. census, the ZIP code 19121, which encompasses much of the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, is 96 percent African American with 39 percent of families below the poverty line (more than four times the national average; U.S. Bureau of the Census 2000: n.p.). SMCC appeared in several city council hearings on reducing violence in Philadelphia in 2005 and 2006, along with several other broad citizen groups such as Mothers in Charge, Men United for a Better Philadelphia, and the Congreso Latino Unido, a Latino community organization.

Interviews with lawmakers at the local level revealed a great deal of civic activism on the part of informal community organizations that connect crime to improving neighborhood conditions and quality of life. In fact, in response to open-ended questions about who lawmakers heard from, all the respondents—city council members and their staff—mentioned citizen groups unprompted, and all discussed at length groups with a broad range of quality-of-life and social justice concerns. By contrast, very few local elected officials mentioned police, and none mentioned prosecutors. In response to a query about who the city council heard from on drug-related crime issues, a Philadelphia city council member who represented a mix of neighborhoods said, “Town watch groups, civic associations, and, in the African American community, a lot of church-based organizations” (Interview 201, 29 June 2003). A former Pittsburgh City Council member also described civic activism by community organizations. When asked what groups she heard from, she responded:

I would hear from residents, community groups, block watches [related to] drug activity and violence, and violence related to guns. Drugs were at the top and gang violence is related to it…. Organizations that were community-based, community empowerment associations, better block development. These groups all wanted the same things—they wanted the drug activity to stop, they wanted housing and community development

(Interview 108, 20 Aug. 2003).One Philadelphia City Council member indicated that he also heard from—and worked with—a group of ex-offenders. “[I've worked with] Ex-offenders. They want to do something positive, so they go to prisons, go to schools. I worked with them on gun legislation and we passed a local gun registry bill” (Interview 207, 20 Aug. 2003).

The strong presence of citizen groups in local crime politics has important implications for how crime and violence are understood. First and foremost, citizen groups that represent a wide range of neighborhood quality-of-life concerns connect crime to larger social problems, including education, jobs, neighborhood blight, and social services (see Reference LyonsLyons 1999; Reference MillerMiller 2001). Many broad citizen groups seemed to find it difficult to talk about crime without implicating a wide range of other social pathologies and neighborhood conditions.

The Director of SMCC testified at a 2006 city council hearing and offered testimony typical of citizen group activists, drawing attention to the relationship between crime and education:

A child that can't read is more likely to get confused, pick up a gun, and commit a murder … maybe the grants [community groups] receive can put a 45-minute dance class, arts, or anger-management class back into the school district curriculum on school premises. Youth engage[d] in positive and interesting classes during school hours are less likely to pick up a gun and shoot someone

(“Blueprint for a Safer Philadelphia,” Philadelphia City Council, Joint Hearing of the Public Safety and Public Health and Human Services Committees, 13 Feb. 2006, p. 182).A representative from the Happy Hollow Advisory Council also noted this connection at the same hearing:

In working with the children at the [Happy Hollow] recreation center, I see that we are raising a lot of our children, you know, in the streets…. We have been successful in putting together programs to keep the children off the street. On Thursday and Friday nights we have games…. We have homework help and things like that that we offer also in the evenings, again to keep the children off the streets and have them in some type of structured activity. Our young men have sports and other activities. We lack activities for our young girls in life skills, in mentoring, and other programs that would help them to develop a strong quality of life and special values

(“Blueprint for a Safer Philadelphia,” Philadelphia City Council, Joint Hearing of the Public Safety and Public Health and Human Services Committees, 13 Feb. 2006, p. 169).Testimony from hearings on gun violence linked the use of guns to their wide availability. At a hearing on gun violence on November 15, 2000, in Philadelphia, a local citizen and member of a group called Ex-Offenders for Community Empowerment noted:

Ex-Offenders for Community Empowerment uses the life experiences of ex-offenders in campaigns to reduce the flow of firearms into our communities and to give youth a chance at a life free of fear … it takes opportunity in order for a crime to be committed. By removing firearms in our communities, we are taking the opportunity away from a crime to happen

(“Public Hearing and Public Meeting Before the Council Committee on Public Safety,” Council of the City of Philadelphia, 15 Nov. 2000, p. 13).Similarly, at a 2004 council hearing on two gun control bills, a representative from Philadelphia Citizens for Children and Youth (PCCY) explicitly suggested that the availability of guns actually creates criminality. “It's not just criminals that get the guns. It's the proliferation of guns in the community that, if someone gets angry, they reach out and [use a gun] and become criminals” (“Public Hearing and Public Meeting Before the Council Committee on Public Safety,” Council of the City of Philadelphia, 9 March 2004, p. 126). PCCY, Ex-Offenders, and other groups such as Father's Day Rally are regular participants in hearings aimed at reducing violent victimization in minority communities.

A second implication of citizen engagement at the local level is that the emphasis on connections between crime and other conditions reorients local crime politics away from punishing offenders and toward harm reduction and helping victims. This is one of the most provocative differences between crime-and-punishment debates at the local level, compared to those at the national level. While victims' rights groups have gained attention over the past few decades, the policy outcome associated with their involvement has tended to equate support for victims with the harsher punishments of offenders (see Zimring et al. 2001). Thus, high-profile, heinous crimes such as child abductions and murders lead to “three strikes you're out,” and shooting rampages lead to five-year mandatory minimum sentences for gun offenses in federal court.

At the local level, such connections are more convoluted. The passage of numerous bills in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in the 1990s and 2000s aimed at regulating guns illustrates this point. Several hearings on gun violence in Philadelphia, for example, were so heavily focused on the public health consequences of guns and the devastation to communities that they featured no testimony whatsoever from witnesses calling for harsher penalties for gun offenders. It is worth quoting at length testimony by a representative from Mothers in Charge, a local anticrime group in Philadelphia who testified at a 2004 hearing on gun violence:

I'm just here today to let Council know that we continue to support any bills that can help take the guns off the street. Mothers in Charge started back in May of last year with about three members. Today, it's over 50. Many of us have lost children to violence. My 24-year-old son, Kalik Jabar Johnson, was shot over a parking space. Mothers in Charge is working around the City to garnish [sic] all types of support around gun legislation that will take guns off the streets. We know that a lot of our children are dying today because of the availability of guns. There are far too many guns on the streets of Philadelphia. To open a Sunday paper and look and see 22 children murdered in the City of Philadelphia, most of them because of gun violence, is horrible. There's devastation with losing a child, but to lose a child to murder, it's the worst thing in the world. Far too many parents in this city are losing children that way. So we are working very hard … with all faith-based initiatives, with the community, with churches, other organizations to garner support for City and State legislation that will work to take guns off the streets. Children should not be able to get the guns the way they do. To go to any corner and be able to get a gun or go to a barber shop, variety store and be able to purchase a gun or to have access to a gun that can take someone's life and cause a devastation that I've seen with so many mothers in our organization, it's a terrible thing

(“Public Hearing and Public Meeting Before the Council Committee on Public Safety,” Council of the City of Philadelphia, 6 April 2004, pp. 8–10).Local advocates also offered ample testimony about why many young people in inner cities feel the need to carry guns. At a 2003 hearing, a representative from the Million Mom March discussed her work with teenagers on this issue:

In these workshops with these kids who are from 13 to 18 years of age … I ask them, “Why should someone own a gun?” and you know, the answers are quite telling. Number one is for protection. The other answer is power. What they feel is powerlessness … conflict resolution is part of the gun violence prevention workshop that we do because we understand that … we have to go back to what the roots of the problem are. We try to give these children, these kids, these young adults, the realization that they have a choice in their actions, but many times they don't see the choices. They only see the hopelessness and the despair

(“Public Hearing and Public Meeting Before the Council Committee on Public Safety,” Council of the City of Philadelphia, 9 March 2003, p. 82).These comments were not unusual in witness testimony at Philadelphia hearings on gun violence; what is remarkable is the lack of attention to offenders, particularly as it is obvious that many speakers had experienced personal losses from gun violence. Even at hearings about legislation to criminalize certain types of gun possession or sale, witnesses rarely talked about offenders getting their just desserts or about local prosecutions at all. What they offered instead was a steady stream of witnessing the day-to-day violence that inheres in many inner-city neighborhoods.

The language of children and kids having access to guns is also noteworthy. By referring to offenders as children, the speakers implied that those using guns are victims themselves—victims of a system that provides ready access to deadly weapons and few opportunities for alternatives. Lawmakers get the message. As one Philadelphia council member put it, “If the federal government gave us more money on front side—providing more money for schools and job opportunities—we wouldn't have to put in so much money on the back side [prisons and police]” (Interview 207, 20 Aug. 2003).

To be clear, local lawmakers consistently reported that all their constituents demanded more police on a regular basis and that there was very little sympathy for violent offenders. Virtually none of the local lawmakers interviewed here—least of all the ones representing minority neighborhoods—indicated that their constituents thought that the law came down too hard on offenders. One Pittsburgh city councilman, a former civil rights activist and representative from a predominantly black neighborhood, said that his constituents had “very little sympathy for criminal actors, whether they are the shooter or the shot” (Interview 103, 10 June 2003). In fact, few of the local crime hearings reviewed here involved criticism of the police, but there was quite a lot of praise. At a 2006 Philadelphia hearing on reducing violence, a representative from the Philadelphia Alliance for Community Improvement told the city council, “[The police] do their job and we know that firsthand, because we've been to find out firsthand for ourselves” (Council of the City of Philadelphia, Joint Hearing of the Public Safety and Public Health and Human Services Committees, 13 Feb. 2006, p. 107). Contrary to conventional liberal conceptions of minority views of crime and the police in national political discourse, the evidence from the two urban locales under study here reveals fairly muted concern for police behavior, which is subverted to more concerted pressure on issues such as education, jobs, neighborhood development, and opportunity.

In other words, the strong desire for more policing is equally matched by strong pressure to improve neighborhood conditions, thereby lessening the likelihood that young people will get into trouble with the law in the first place. A Pittsburgh councilwoman put it this way with respect to drug violence: “The community wants really bad guys locked up. They don't want their lives to be in jeopardy. But they also wanted us to get to the root of the drug dealing” (Interview 103, 10 June 2003).

This message of impressionable children being subjected to neighborhood conditions that promote criminality and the need to address social problems such as education, job, and recreation opportunities before they generate street criminals is largely lost as crime issues make their way to higher levels of government, while support for getting violent criminals off the streets is magnified. In stark contrast to the victim-centered approaches of local groups pressuring lawmakers on guns, for example, national gun debates have largely resulted in the ratcheting up of penalties for crimes committed with a gun or anemic regulations that are difficult to enforce, later reversed, or declared unconstitutional.Footnote 16 Locally, few advocate such consequences, not because they have less punitive views but because they are focused on a wider set of problems. Few believe that locking up offenders for longer will stem the tide of gun violence because it is clear that one offender is quickly replaced with another.

This illustrates one of the central problems when crime politics migrate from local to national levels. The “get the guns off the street” language of local advocacy groups, while broad and open-ended in its policy implications, is most easily transmitted as a “lock up the gun offenders and throw away the key” strategy. Even the national civil rights and public interest groups that might serve as a counterweight and promote a broader social agenda—such as the NAACP, ACLU, or American Friends Service Committee—are drawn into the dichotomies of single-issue national crime politics such as police misconduct or penalties for gun and drug offenses, none of which directly confront the very real social welfare issues that are given voice in local urban neighborhoods.

The emphasis on punishment perpetuates an individualistic approach to crime that is conducive to national crime politics where single-issue groups and criminal justice agencies dominate. Racialized innocent victims and dangerous felons collide in the public and legislative imaginations to strengthen punishments and enhance criminal justice agency budgets. Indeed, such individualizing frameworks can also be seen in popular films, even when they are ostensibly aimed at delving deeper into racial problems. Popular movies such as American History X and Crash, while telling a more nuanced story about race in American culture than average, still perpetuate a very individualistic notion of racial problems. The story lines emphasize the transformations of individuals with little reference to the long history of political decisionmaking that has contributed to racial disparities today. Such individualistic approaches to thinking about race in American society contribute to the likelihood that criminal penalties in national politics will emphasize individual culpability and decouple crime from broader socioeconomic cleavages. But such cleavages strike at the heart of racial disparities in victimization and incarceration. Locally, participants in the political process are living with the day-to-day realities of crime and violence, along with a host of other problems facing their communities. Legal narratives in these contexts privilege victims—of crime, poor schools, urban blight, and so on—and emphasize remediating the conditions that make victimization likely.

Conclusion

A wide range of interdisciplinary scholarship directly connects the high rates of arrest and incarceration of blacks and Latinos to their living conditions (Reference Massey and DentonMassey & Denton 1993; Reference Sampson and MorenoffSampson & Morenoff 2002; Reference WalkerWalker et al. 1996), but the lawmakers in the political venues best situated to address these conditions are largely insulated from the political pressure to do so. What does this insulation mean for the politics of crime and punishment and racial inequality in the United States? This analysis has suggested three ways in which American federalism structures representation on crime and violence in ways that disadvantage low-income racial minorities. First, the American political system makes it fairly easy to decouple crime and punishment from larger socioeconomic inequalities through a central lawmaking apparatus that is ill equipped to sustain attention to the connection between crime and larger social issues. Members of Congress are rarely held accountable for their positions on local crime problems, but there are multiple incentives for them to respond to single-issue interest groups, professional associations, and criminal justice agencies eager to have their missions enhanced. These groups are more likely to converge on increasing punishment than on ameliorating poor living conditions. In contrast, while many broad citizen interest groups are not opposed to more punishment, they also exhibit a strong pragmatic streak and are wary of policy prescriptions that have little visible impact on the condition of their communities. Local lawmakers must respond to these demands for community revitalization but are highly constrained in their ability to significantly address economic conditions. The disconnect between those held accountable and those with the means to promote viable solutions is substantial.

Second, American federalism reinforces existing race and class stratification by creating a system of multiple political venues that makes it difficult for poorly resourced groups to navigate and by driving several layers of government between citizens who experience these problems and lawmakers who have the capacity to ameliorate them. Creating and sustaining groups is a difficult enterprise under the best of circumstances, but having the resources and knowledge to sustain a presence on multiple legislative venues simultaneously requires extraordinarily well-organized and highly resourced participants. These groups are unlikely to regularly include the interests of poor, urban minorities. While multiple legislative venues may provide a more open political system in some respects, it also creates a political context that perpetuates racial hierarchy by creating opportunities for highly resourced groups to control the terms of the debate and forcing the less organized onto their terrain, no matter how they may initially frame the problem. This is dramatically illustrated by how local pressures for improvements to neighborhood public safety and quality of life are truncated and transformed in national discourse into dichotomous debates over more or less drug enforcement, gun control, or policing. None of those debates strike at the heart of the urban conditions that drive so many people into local politics to advocate on behalf of their communities.