Historically, many people with intellectual disability were cared for in long-stay hospitals for those with a ‘mental handicap’. All their physical and mental health needs were meant to be provided for in these institutions and they seldom came into contact with generic services. Following the deinstitutionalisation movement of the 1980s, these long-stay hospitals were closed. The number of long-stay beds fell from around 64 000 in 1970, to well under 10 000 by 2001 (NHS England 2013) and around 3954 by 2012–2013 (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013). The role of psychiatrists involved in this field changed too. From being ‘mental handicap doctors’ who dealt with all aspects of individuals’ physical and mental healthcare, they now became specialists primarily responsible for managing their mental health and behavioural problems.

Current government policy in the UK expects that, wherever possible, people with intellectual disability should be enabled to use generic health services (Department of Health 2001). Although the equity of access that mainstreaming brings is very pleasing, it is meaningless if not accompanied by equity of outcome. This is a particular problem for those with intellectual disability who have mental health and/or severe behavioural problems. Compared with the general population, people with intellectual disability have higher rates of mental health problems (Reference Cooper, Smiley and MorrisonCooper 2007; Reference Morgan, Leonard and BourkeMorgan 2008), their clinical presentations are often unique and their responses to treatment potentially different. In many cases, therefore, the identification and treatment of their comorbid mental health problems require specialist expertise both in generic and specialist settings (Reference Bjelogrlic-Laakso, Aaltonen and DornBjelogrlic-Laakso 2014; Department of Health 2015). In this regard, the UK with its specialist postgraduate training in the psychiatry of intellectual disability is in a position of unique strength. It is because of an acknowledgement of these particular mental healthcare needs that this country has introduced specialised intellectual disability teams providing a range of services in both community and inpatient settings (Reference LindseyLindsey 2000).

In-patient units for people with intellectual disability and mental health or behavioural problems (described as assessment and treatment units) in the UK have come under scrutiny as a result of BBC television’s Panorama programme ‘Undercover care: the abuse exposed’. Following its broadcast in May 2011, a number of reports (Department of Health 2012a,b) described assessment and treatment units as a new form of institutional care that had no place in the 21st century and concluded that there were too many people staying for too long in these units. However, describing all in-patient services for people with intellectual disability as ‘assessment and treatment units’ ignores the existence of various categories of bed provision that serve completely different functions. This article seeks to clarify in-patient services for the treatment of mental health and behavioural problems in people with intellectual disability, focusing on why they are needed, the different bed categories and ways of monitoring standards and outcomes.

The need for in-patient services

The need for in-patient services to treat people with intellectual disability has to be considered in the context of the mental health difficulties and challenging or problem behaviours in this population.

Comorbid mental health problems

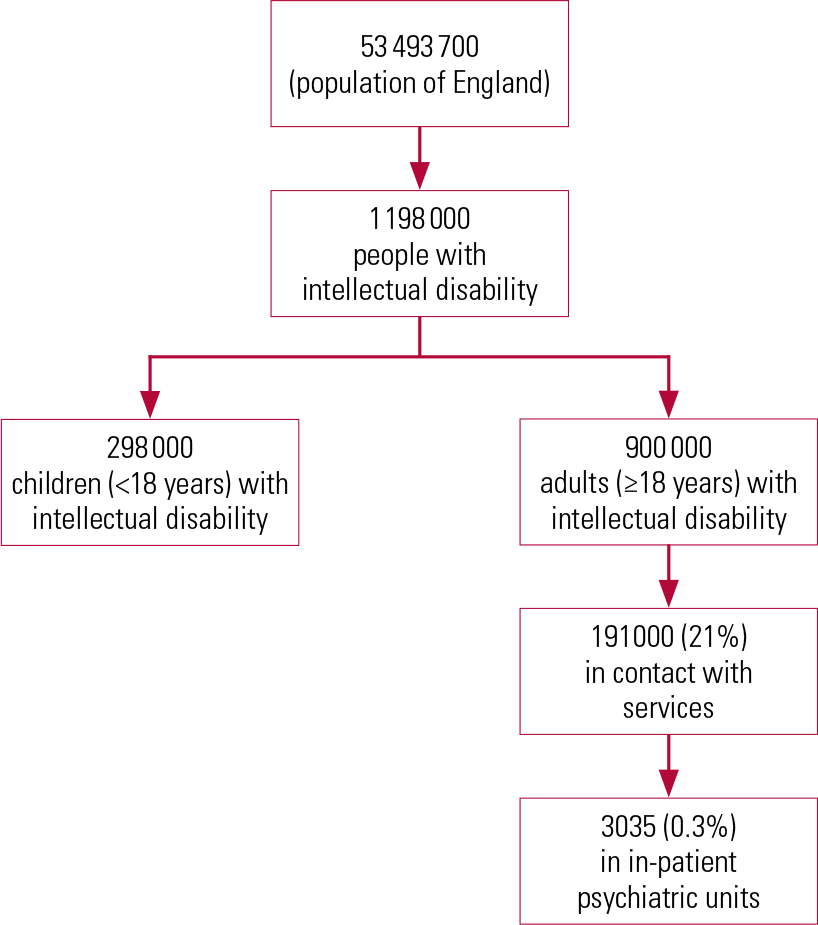

Intellectual disability is a condition characterised by significant impairments of both intellectual and adaptive functioning and an onset before the age of 18 (World Health Organization 1992). The term ‘disorders of intellectual development’ is also used and the UK health services currently use the term ‘learning disability’ to describe this group. About 1–2% of the general population will have an intellectual disability (Reference Emerson and BainesEmerson 2010). The degree of intellectual disability is categorised as mild, moderate, severe or profound, with over 90% of those affected falling within the mild range (Department of Health 2001). In England, with a population of about 53 million, around 900 000 adults have an intellectual disability, but only 191 000 (21%) of these are in contact with intellectual disability services (Reference Emerson and BainesEmerson 2010) and 3035 (0.3%) are receiving treatment in in-patient psychiatric units at any point in time (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2013) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Community and in-patient service use by people with intellectual disability in England (Reference Emerson and BainesEmerson 2010; Health and Social Care Information Centre 2013).

People with intellectual disability have high rates of comorbid mental health problems. Epidemiological studies have suggested a prevalence rate of 31 to 41% (Reference Cooper, Smiley and MorrisonCooper 2007; Reference Morgan, Leonard and BourkeMorgan 2008). For those treated in non-secure hospital settings, figures from specialist intellectual disability in-patient units show rates of comorbid major mental illness ranging from 50 to 84% (Reference Alexander, Piachaud and SinghAlexander 2001; Reference Tajuddin, Nadkarni and BiswasTajuddin 2004; Reference Hall, Parkes and HigginsHall 2006a,Reference Hall, Parkes and Samuelsb). This is in addition to other comorbid conditions, such as autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), personality disorders and substance misuse. Similarly high figures are reported for those treated in secure hospital services for people with intellectual disability: up to 50% have a personality disorder, up to 30% have an autism spectrum disorder, about 30–50% have a major mental illness, about 30–50% have substance misuse/dependence and about 20% have epilepsy (Reference Alexander, Piachaud and OdebiyiAlexander 2002, Reference Alexander, Crouch and Halstead2006; Reference Plant, McDermott and ChesterPlant 2011). Some of these conditions present with challenging behaviours and some do not.

Challenging behavior

Challenging behaviour has been defined as behaviour that, because of its intensity, frequency or duration, poses a threat to the quality of life and/or physical safety of the individual or others and is likely to lead to restrictive or aversive responses or exclusion (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2007). It is a socially constructed, descriptive concept that has no diagnostic significance and makes no inferences about aetiology. It encompasses heterogeneous behavioural phenomena in different groups of people and may be either unrelated to psychiatric disorder or a primary or secondary manifestation of it (Reference Xeniditis, Russell and MurphyXenitidis 2001). In people with intellectual disability who come into contact with health services, it can range from stereotypies and self-injury in a person with a profound intellectual disability to violent offences in someone with a mild intellectual disability. Not all of those who present with challenging behaviour that involves aggression are arrested, charged or convicted (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014).

Addressing challenging behaviour

The therapeutic approach to challenging behaviour has been well described and emphasises the use of the least restrictive community resource wherever possible (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2007). Inpatient admission to a psychiatric unit is required only if the risk posed by the behaviour is of such a degree that it cannot safely be managed in the community or if an early assessment is required in a safe setting where the patient can be monitored by specialists to ascertain the underlying cause of the behaviour, which may very well be a mental health problem.

The assumption that all behavioural problems in people with intellectual disability were a consequence of institutional lifestyles and that they would diminish once community care was introduced may be flawed (Reference Holland, Clare and MukhopadhyayHolland 2002). People with intellectual disability and mental health or behavioural difficulties living in the community require access to in-patient services for a number of reasons. First, behaviours previously hidden or tolerated within institutions are more visible in the community and they are more likely to have adverse consequences (Reference Moss, Emerson and BourasMoss 2002). An increased societal aversion to risk (Reference Carroll, Lyall and ForresterCarroll 2004) makes this dynamic more potent. Challenging behaviour, whether it is aggression or self-injury, can pose a level of risk that is deemed unacceptable in a community setting. Consequently, in-patient settings of varying degrees of security may be needed for varying periods of time. The guiding principle is to choose the least restrictive option.

Second, any patient who is seen as ‘liable to be detained’ under the Mental Health Act 1983 will by law require a hospital bed (R v Hallstrom ex parte W [1986] 2 All ER 306).

Third, as already mentioned, people with intellectual disability have higher rates of comorbid psychiatric disorder. Their clinical presentations are often a complex mix of intellectual disability, mental illness, personality disorder, pervasive developmental disorder and other developmental disorders (e.g. hyperkinetic disorder). The natural course of mental disorders suggests that these individuals might experience periods of crisis as well as long-term behavioural symptoms that persist despite treatment. In both situations, they may need a safe setting where professionally qualified staff can treat them with continuous nursing observation, behavioural monitoring and multidisciplinary professional input beyond what can be reasonably achieved safely in the community.

Finally, many people with intellectual disability and mental health problems also have a wide range of physical disorders, including epilepsy (Reference Emerson and BainesEmerson 2010), that further complicate their presentations. In some people who present with challenging behaviour, these mental and physical health problems are intricately linked and often it can be difficult to tease out whether the presentation is because of an underlying organic (physical) condition. In many of these complex presentations, an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment require continuous nursing observation, physical investigations, and medical and psychiatric expertise in an in-patient setting.

Types of in-patient bed

A report published by the Faculty of Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability at the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2013) gives a detailed description, illustrated with a number of case vignettes, of the purpose and functions of the different types of in-patient bed for people with intellectual disability in the UK.

These different categories of hospital bed (Box 1) are best understood within the context of a tiered-care model of service provision, with tiers 1 (liaison working with other agencies) to 3 (intensive case management in the community) constituting community intellectual disability services and tier 4 constituting the in-patient element of care (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2011) (Fig. 2). For a smooth patient journey through these tiers, it is generally acknowledged that health and social care commissioners and providers must take a ‘whole-systems’ approach to commissioning and providing care.

BOX 1 Bed categories in the UK

In-patient beds for people with intellectual disability and mental health and/or severe behavioural problems are divided into 6 categories

-

Category 1: High, medium and low secure forensic beds

-

Category 2: Acute admission beds in specialised intellectual disability units

-

Category 3: Acute admission beds in generic mental health settings

-

Category 4: Forensic rehabilitation beds

-

Category 5: Complex continuing care and rehabilitation beds

-

Category 6: Other beds, including those for specialist neuropsychiatric conditions and short breaks

FIG 2 Tiered model of care for intellectual (learning) disability services (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2011: p. 23).

Until recently category-specific information on bed provision for people with intellectual disability has been limited. This is because the information that healthcare providers must supply when they seek registration with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) to operate in the UK has been shaped by the Health and Social Care Act 2008. Consequently, they need give only limited details about the categories and purpose of bed provision for people with intellectual disability and mental health or behavioural problems. It is now acknowledged that the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ categorisation of bed types as described in Box 1 is a cogent articulation of the range of in-patient environments serving different assessment and treatment purposes. As an endorsement of this, the recent Learning Disability Census (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2013) collected data from providers using these categories.

Category 1 (high, medium and low secure beds)

Secure beds are for patients who pose a level of risk assessed as requiring the physical, relational and procedural security of a high, medium or low secure unit. The general characteristics of these units are described elsewhere (Reference KennedyKennedy 2002; Reference PhillipsPhillips 2007; Reference Tucker and HughesTucker 2007; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013). All patients accessing these beds tend to be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 (amended 2007). These services offer an integrated, multidisciplinary model of support within an environment that emphasises care and treatment rather than punishment (Reference HollinsHollins 2000).

The decision whether or not a person needs a secure bed often depends on clinical judgements about risk and the attitudes of professionals working in the criminal justice, health and social care systems. These attitudes and decisions are in turn shaped by the availability of resources and hence if less restrictive in-patient settings are unavailable or inaccessible, then the use of secure beds can go up.

The length of stay in secure units is dictated by several factors, including public attitudes to risk, duration of treatment programmes, response to treatment and the availability of appropriate step-down facilities. A streamlined process exists in some regions for access to these units: a clinician (usually from the patient’s local area) carries out an access assessment and the patient’s relational, structural and procedural security needs and treatment requirements are established before a commissioning decision is made. In addition to reviews by first-tier tribunals (mental health), these placements are also reviewed at regular intervals by the commissioners who source and fund the placement and the access assessors to see whether patients can move to less restrictive placements.

Category 2 (acute admission beds in specialist intellectual disability units) and category 3 (acute admission beds in acute mental health wards or in such wards with a specialist intellectual disability function)

Category 2 and category 3 beds are intended for the assessment and treatment of acute severe mental health and/or behavioural problems which pose a risk that cannot be safely managed in the community, but does not meet the threshold to be considered for a secure bed. These units complement community services and are to be used for a short period to mitigate risk therapeutically and to enable a thorough assessment of mental health needs by specialist staff in a controlled environment. Access to either of these bed categories should be informed by clinical need and patient choice.

The literature comparing these two models is well summarised in two elegant structured reviews (Reference ChaplinChaplin 2004, Reference Chaplin2009). The studies included were controlled trials or descriptive surveys drawn from the UK, USA, Canada and Australia. The main conclusions are summarised in Box 2.

BOX 2 Category 2 and 3 beds – the evidence

-

There is no conclusive evidence to favour either model (i.e. category 2 or category 3 beds)

-

The two models serve different types of patient and this partially explains the differences in length of stay

-

People with severe intellectual disability were not well served by generic services (i.e. category 3 beds)

-

There was a worse outcome for people with intellectual disability in generic settings, particularly in the older studies; this poor outcome was improved if a specialist intellectual disability component was introduced into the generic setting

-

Generic psychiatric care for people with intellectual disability is unpopular, especially with carers; again, this is improved by specialist input

-

The provision of generic psychiatric care without specialist intellectual disability input is not sufficient to meet the needs of people with intellectual disability

Category 4 (forensic rehabilitation) and category 5 (complex continuing care and rehabilitation)

These two categories refer to in-patient provision for patients whose mental health problems and behavioural difficulties remain intractable despite evidence-based treatment. These patients continue to need the structure, security and care offered by a hospital setting for long periods of time. Category 4 is mostly for people who have stepped down from category 1 beds, but who show enduring risky behaviour towards themselves or others. Many of these patients have committed serious offences and may be subject to restrictions from the Ministry of Justice. Although they have gone through offence-specific and other treatment programmes, their current risk assessments still emphasise the need for robust external supervision and ongoing treatment. They tend to have long durations of stay, often running into years, but it is the availability of category 4 beds, often in locked or open community units, that allows them to receive treatment in a less restrictive setting than a secure unit.

Category 5 is mostly for people who have undergone the initial intensive treatment process. Their diagnostic and psychological formulations are available and they have received a range of biopsychosocial treatments. However, for a variety of reasons (including treatment-refractory enduring mental illness, severe behavioural challenges that have not responded adequately to treatment, ongoing risks of neglect or vulnerability, and persisting risks to the safety of others), a safe transition into the community has not been possible even with adequately resourced community provisions. The provision of a stable, structured and predictable environment with qualified staff who can continue to offer physical and psychosocial treatments that incorporate positive risk-taking offers the best quality of life to these patients. Category 5 thus provides a process of rehabilitation and re-skilling for a transition to community settings. This is usually tailored to each individual’s pace of progress, so durations of stay tend to be long. If these beds were not available, the potential consequence might be ‘revolving door’ patterns of hospital admission.

Category 4 and 5 beds are not unique to those with intellectual disability. Their definitions closely mirror those of the longer-term complex/continuing care units described by the NHS Confederation (2012) in its report Defining Mental Health Services.

Category 6 (other types of bed)

This category includes specialist beds for neuro-psychiatric conditions such as epilepsy and movement disorders. At present, this service provision is limited to a few specialised national units.

Current intellectual disability in-patient provision in England

In 2013 there were 3901 intellectual disability beds across four NHS regions in England: 2369 category 1; 814 category 2; 593 categories 4/5; and 125 category 6 (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013). These include all NHS and independent sector provision for forensic and non-forensic services and represent an almost 90% reduction from a high of over 33 000 beds in the NHS sector alone in 1987–1988 (NHS England 2013). The occupancy rate for these beds, although difficult to determine precisely, is estimated to be around 80%, which is in keeping with the best practice guidelines for bed occupancy in in-patient mental health settings (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2011).

The Learning Disability Census (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2013) reported that there were 3250 people with intellectual disability in in-patient units across 104 service locations in England on 30 September 2013. The level of response and numbers were consistent with the last Count Me In census in 2010 (Care Quality Commission 2011). A time series analysis in the latter covering the years 2006–2010 showed that the number of people with intellectual disability and comorbid autism in in-patient units on the census days fell from 4435 in 2006 to 3376 in 2010. Although the trend shows a downward trajectory there are still too many patients who spend long periods in in-patient units, some of which are considerable distance from their home communities: 60% of these patients (1949) had been in hospital for a year or more and 18% (570) were in hospitals 100 km or more from their residential postcode. Further analysis of length of stay for each bed category in these units is required. This is because a length of stay appropriate for a category 1 forensic bed may be thoroughly inappropriate for a category 2 or 3 acute admission bed. A notable change from the 2010 Count Me In census is that in 2013 the majority of individuals (76%, 2481 people) were in-patients on wards that were predominantly for people with intellectual disability.

Although economies of scale may hamper efforts to provide all categories of bed in every district, the emphasis should be on the provision of in-patient services as close to the person’s place of residence as possible. When planning service provision, it is therefore important to consider all in-patient beds, whether ‘secure’ or ‘non-secure’, as a whole to ensure smooth transition of care between community and in-patient services depending on patients’ needs. It is good practice to commission and provide category 2, 3, 4 and 5 beds locally to enable the involvement of local teams and communities, and category 1 beds regionally. It has been suggested that, in addition to well-developed community teams, 6–7 in-patient beds across all six categories may be needed per 100 000 population, although the number will differ greatly depending on local service configurations (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013). If, in the absence of significantly improved community services, the less restrictive in-patient facilities (categories 2–5) are cut down, then many more people will potentially have unmet needs that compromise their mental health and safety and could end up in far more restrictive secure beds (category 1). This may be one of the reasons for the higher numbers in category 1 compared with categories 2–6 in the recent census (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2013).

At present, 70% of secure (category 1) beds are in low secure units. Since the provision of relational and procedural security is often more important than physical security for people with intellectual disability, many patients currently in these beds could move to the less restrictive rehabilitation beds (category 4 or 5). At present, this is problematic because the commissioning streams are different and there is significant geographical variation in the current distribution of beds.

A number of patients in category 4 and 5 beds (forensic rehabilitation and complex continuing care) stay in hospital for very long periods because, apart from therapeutic care, they also need continuous supervision for the protection of the public. If this type of supervision were legally enforceable in the community, without it amounting to the legal standard for de facto detention or deprivation of liberty, then they could very well live in the community.

Monitoring standards and outcomes

Assessing the quality of service provided in inpatient units rests on two key questions – first, is the treatment carried out to an adequate standard as defined by current clinical practice, and second, does the treatment work.

Accreditation tools focus on process variables in in-patient units and ensure that clinical practice is in keeping with standards approved by peers. There are several such tools, including the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Accreditation for Inpatient Mental Health Services in Learning Disability (AIMS-LD) for categories 2, 3 and 5 (Reference Cresswell, Bleksley and LemmeyCresswell 2010) and the peer review accreditation process for categories 1 and 4 (Reference PhillipsPhillips 2007; Reference Tucker and HughesTucker 2007, Reference Tucker, Iqbal and Holder2012).

The measurement of process variables has to be supplemented with information about whether treatment provided in these settings works. A minimum data-set of outcome variables that cover measures of clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience has been determined for this purpose (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013: Tables 3 and 4, free online access).

It is important that these in patient services have robust arrangements for clinical governance to ensure that they are safe, effective and provide a positive patient experience. A number of good practice guidelines are listed in Box 3.

BOX 3 Good practice points

-

1 Service providers, commissioners and policy makers should be aware of the different categories of bed: these serve very different functions and any accreditation or inspection reports by regulatory authorities should specify bed categories.

-

2 A choice of both generic and specialist intellectual disability beds should be available for people with intellectual disability and mental health or behavioural problems who require acute in-patient psychiatric treatment. This choice should be driven by individuals’ health and social care needs.

-

3 Regional commissioning strategies should focus on care pathways that include both well-developed community services and all six categories of in-patient bed.

-

4 To reduce the need for admission and shorten the length of stay in hospital, intellectual disability healthcare providers, mental health providers and local authorities should adopt a whole-systems approach to service provision.

-

5 Availability of multidisciplinary therapeutic care distinguishes good in-patient facilities from those that are no more than settings of containment. There should be regular monitoring of this availability through the care programme approach and other reviews.

-

6 All in-patient units should be able to show evidence of having gone through an external accreditation process such as the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ peer review accreditation for forensic beds, AIMS-LD or any other equivalent.

-

7 All in-patient units should be able to show evidence of a minimum data-set of treatment outcomes that includes baseline descriptions and measures of efficacy, patient safety and patient experience.

(Adapted from Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013)

Conclusions

Currently in the UK, the vast majority of people with intellectual disability live fairly independent lives in the community, with only about 21% of adults with the condition having any contact with specialist intellectual disability services. However, they do have high rates of comorbid mental health problems: epidemiological studies show a prevalence rate of 31–41% (Reference Cooper, Smiley and MorrisonCooper 2007; Reference Morgan, Leonard and BourkeMorgan 2008).

With well-resourced and well-trained community teams, these problems can be adequately treated in the community setting and unnecessary psychiatric hospital admissions can be avoided. Even with very good community teams, however, in-patient psychiatric services will continue to be needed, particularly if continuous nursing observation or behavioural monitoring and professional input beyond what can be safely achieved in the community are required. Availability of this resource will therefore remain an important component of achieving equity of treatment outcomes for this often marginalised group of individuals.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The rate of mental disorders in people with intellectual disability:

-

a is lower than that in people without an intellectual disability

-

b is the same as that in people without an intellectual disability

-

c is higher than that in people without an intellectual disability

-

d has not been measured before

-

e is lower in those in in-patient settings than those living in the community.

-

-

2 The proportion of adults with intellectual disability who are in contact with learning disability services in England is:

-

a 10%

-

b 21%

-

c 39%

-

d 57%

-

e 75%.

-

-

3 The number of categories of in-patient bed described in the UK for people with intellectual disability and mental health problems is:

-

a 1

-

b 2

-

c 6

-

d 8

-

e 10.

-

-

4 The bed category that constitutes secure in-patient care is:

-

a category 1

-

b category 2

-

c category 3

-

d category 4

-

e category 5.

-

-

5 Which of the following is not a proposed minimum data-set measure of outcome variables?

-

a measure of effectiveness

-

b measure of patient safety

-

c number of in-patient beds

-

d measure of patient experience

-

e measure of aggression.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | b | 3 | c | 4 | a | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.