Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease with a broad global distribution (Murray et al. Reference Murray2005). The main clinical forms of leishmaniasis are visceral leishmaniasis (VL), cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) (Murray et al. Reference Murray2005).The disease has infected 12 million people worldwide and is endemic in 88 countries (Alvar et al. Reference Alvar2012). According to estimation, the annual incidence of CL and VL are 0.7–1.2 and 0.2–0.4 million new cases, respectively, with mortality rates of 20 000–40 000 cases (Alvar et al. Reference Alvar2012).

The causative agents of VL are four species of the genus Leishmania, including L. infantum, L. donovani and L. archibaldi in the old world (i.e. Europe, Asia and Africa) and L. chagasi in the New World (i.e. the American) (Guerin et al. Reference Guerin2002; Quinnell and Courtenay, Reference Quinnell and Courtenay2009). However, in the new classification, clinically and epidemiologically VL is divided into two main forms: (1) zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis (ZVL) caused by L. infantum that occurs in Asia, North Africa, Europe, South and Central America. ZVL affects mainly young children and the domestic dogs are its principal reservoirs. (2) Anthroponotic visceral leishmaniasis (AVL) caused by L. donovani exists in India, parts of the Middle East and East Africa. AVL affects people of all ages and transmits from human to human by infected sand fly bite (Choi and Lerner, Reference Choi and Lerner2001; Lukeš et al. Reference Lukeš2007; Quinnell and Courtenay, Reference Quinnell and Courtenay2009). CL is caused by L. tropica, L. major and L. aethiopica in the old world and L. braziliensis, L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, L. guyanensis and L. panamensis in the new world (Murray et al. Reference Murray2005; Alvar et al. Reference Alvar2012; McGwire and Satoskar, Reference McGwire and Satoskar2014). Also, L. braziliensis is a causative agent of MCL in the new world (McGwire and Satoskar, Reference McGwire and Satoskar2014). However, an interstitial form of leishmaniasis, which known as viscerotropic leishmaniasis is caused by main causative agents of CL, in particular L. tropica and L. mexicana (Barral et al. Reference Barral1986; Sacks et al. Reference Sacks1995; Monroy-Ostria et al. Reference Monroy-Ostria, Hernandez-Montes and Barker2000; Choi and Lerner, Reference Choi and Lerner2001; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss2009). Viscerotropic leishmaniasis clinically differs from VL. VL causes signs and symptoms including fever, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, emaciation, pancytopenia and hyperglobulinaemia, while viscerotropic leishmaniasis causes non-specific symptoms including high fever, malaise, intermittent diarrhoea and abdominal pain without the classic signs or symptoms of VL (Barral et al. Reference Barral1986; Sacks et al. Reference Sacks1995; Monroy-Ostria et al. Reference Monroy-Ostria, Hernandez-Montes and Barker2000; Choi and Lerner, Reference Choi and Lerner2001; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss2009). Hence, we performed a systematic review of the cases of viscerotropic leishmaniasis to present the main causative agents and clinical appearance of the diseases.

Materials and methods

An electronic search without language restrictions was performed using Medline, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar (any date to August 2017). The search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al. Reference Moher2015). The terms and search strategy are described in Table 1. All titles, abstracts and full texts from each of the searches were examined and reviewed. The search was limited to literatures on humans. Moreover, all selected references were hand-searched for other relevant articles or their citations in Google Scholar. Data selection was also performed after removing duplications by Endnote software (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon2015). Articles were considered eligible for inclusion if they involved case reports or case series of patients with VL who infected with one of Leishmania species that regularly causing CL. Also, an article was selected if it reports details of diagnostic tests (e.g. molecular methods or isoenzyme identification) or relevant evidence to confirm the species of Leishmania parasite.

Table 1. Search strategy and terms used to identify studies on visceral leishmaniasis due to different Leishmania species

Results

The search identified 52 relevant studies after removing duplicates. Finally, 19 out of the 52 articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). (Mebrahtu et al. Reference Mebrahtu1989; Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993, Reference Hernández1995a, Reference Hernándezb; Magill et al. Reference Magill1993; Sacks et al. Reference Sacks1995; Hanly et al. Reference Hanly, Amaker and Quereshi1998; Ramos-Santos et al. Reference Ramos-Santos2000; Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo2002; Silva et al. Reference Silva2002; Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi, Rasouli and Shamsizadeh2006, Reference Alborzi2008; Aleixo et al. Reference Aleixo2006; Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss2009; Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010; Mestra et al. Reference Mestra2011; Shafiei et al. Reference Shafiei2014; Bamorovat et al. Reference Bamorovat2015).

Fig. 1. Flow of diagram through the different phases of the review.

The articles describing the history of 30 human cases (Tables 2–5). One article was excluded because the study was retrospectively reported five cases of VL in the city of Tabuk in Saudi Arabia without evaluation of Leishmania species by specific diagnostic tests. We also could not find the full text of the article (Hanly et al. Reference Hanly, Amaker and Quereshi1998). Also, one case had been reported in two different journals by the same authors in 1993 and 1995 (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993, Reference Hernández1995a); but, the last publication described further clinical manifestation of the patient (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1995a). We also found five articles that reported six cases of VL in dog due to L. tropica (Guessous-Idrissi et al. Reference Guessous-Idrissi1997; Lemrani et al. Reference Lemrani, Nejjar and Pratlong2002; Hajjaran et al. Reference Hajjaran2007; Mohebali et al. Reference Mohebali2011; Bamorovat et al. Reference Bamorovat2015; Sarkari et al. Reference Sarkari2016). These cases are presented in supplementary Table 1.

Table 2. The number of cases that reported from endemic regions

a Indicated American soldier return from Saudi Arabia.

b Indicated an Afghani girl who lived in the USA.

c Indicated an Italian man living in Venezuela.

Table 3. Visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in human

Table 4. Visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major in human

Table 5. Visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. braziliensis, L. amazonensis and L. mexicana in human

Countries

According to the Table 2, the cases were reported from 10 countries. Leishmania tropica was reported from Iran (five cases) (Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi, Rasouli and Shamsizadeh2006, Reference Alborzi2008; Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010), American soldier returned from operation desert storm in Saudi Arabia (eight cases) (Magill et al. Reference Magill1993), India (four cases) (Sacks et al. Reference Sacks1995), Kenya (two cases) (Mebrahtu et al. Reference Mebrahtu1989) and the Afghan girl who lived in the USA (one case) (Weiss et al. Reference Weiss2009). Leishmania major was reported from Iran (two cases) (Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007; Shafiei et al. Reference Shafiei2014) and Burkina Faso (one case) (Barro-Traore et al. Reference Barro-Traore2008). Leishmania braziliensis was reported from Brazil (two cases) (Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo2002; Silva et al. Reference Silva2002) and an Italian man living in Venezuela (one case) (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993). Leishmania mexicanawas reported from Colombia (Mestra et al. Reference Mestra2011) (one case) and Mexico (one case) (Ramos-Santos et al. Reference Ramos-Santos2000). One case of L. amazonensis was reported from Brazil (Aleixo et al. Reference Aleixo2006) and one case of Leishmania variant that shared sequences of L. braziliensis and L. mexicana from Venezuela (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1995b) (Table 2).

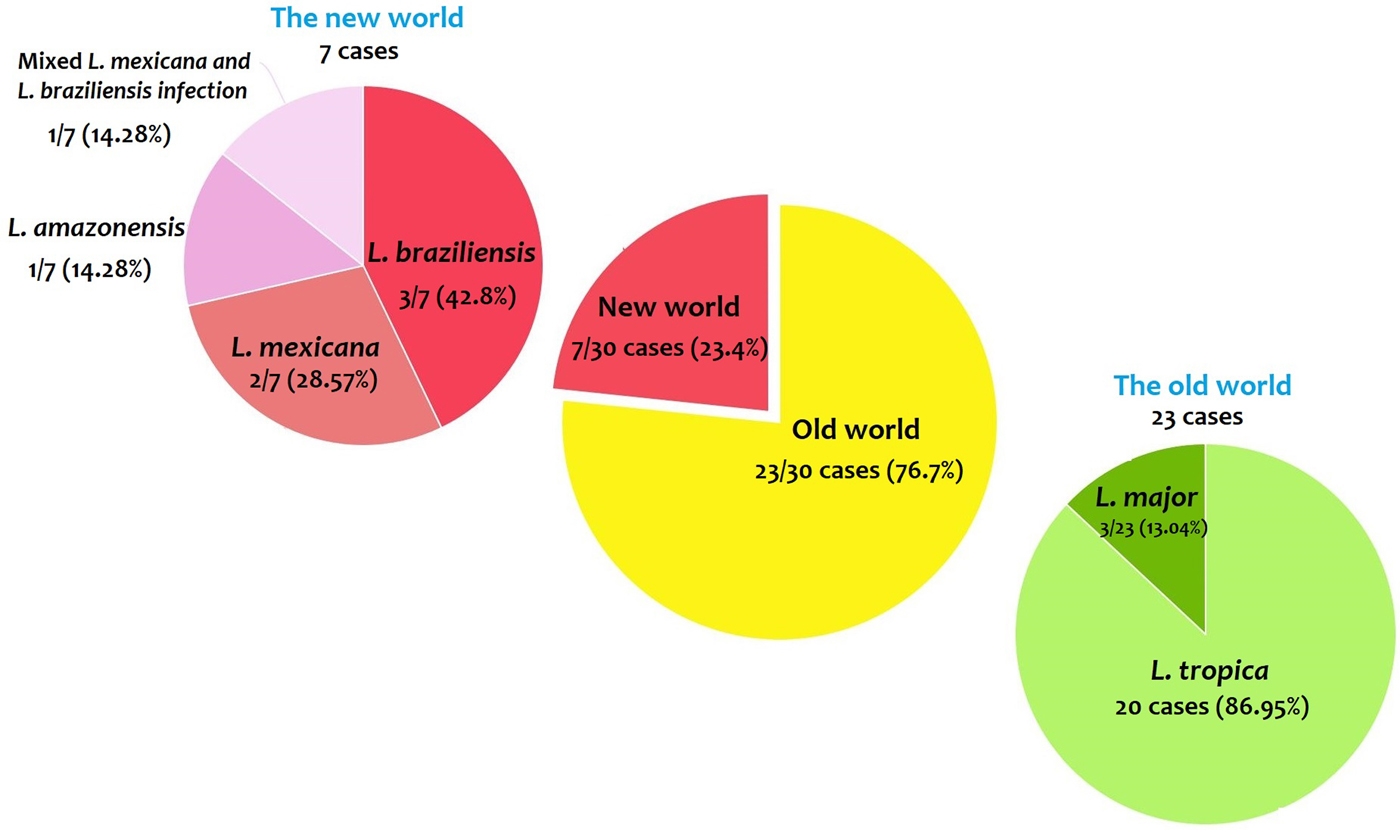

Leishmania species

From 30 cases, old and new world Leishmania species were reported from 23 (76.7%) and seven (23.4%), respectively (Fig. 2). From the 23 cases with the old world species, L. tropica and L. major were reported from 20 (86.95%) and three (13.04%) cases, respectively (Tables 2–3). While, new world Leishmania species, including L. braziliensis, L. mexicana and L. amazonensis were reported from three (42.8%), two (28.57%) and one (14.28%) cases, respectively. Also, one article reported a case (14.28%) with a variant of Leishmania that shared sequences of L. braziliensis and L. mexicana (Tables 4 and 5).

Fig. 2. Prevalence of the old and new world Leishmania species.

Sex and age of the patients

The infection was higher in male (24/30, 80%) than female (5/30, 16.7%) patients (Fig. 3 and Tables 3–5). The sex was not reported in a case report as well (Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi, Rasouli and Shamsizadeh2006). From the old world Leishmania-infected patients, L. tropica was detected in 16 (80%) and three (15%) out of 20 cases of male and female patients, respectively (Table 1), but the sex was not reported in an L. tropica-infected patients (Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi, Rasouli and Shamsizadeh2006). All of the three cases of L. major were reported from male patients (Table 4). From the seven cases with the new world Leishmania-infection, five (71.4%) and two (28.6%) cases were reported from male and female, respectively (Table 5).

Fig. 3. Prevalence of the infection in males and females.

Among the L. tropica-infected patients (n = 20 cases), seven and six cases were reported from patients with age ranges of 2–15 and 17–50 years old, respectively. The age was not reported in six out of 20 L. tropica-infected patients (Table 3). All of the three L. major-infected patients were adult with age ranges of 31–53 years (Table 4). Among the seven patients with the new world Leishmania infection, six patients were in the adult aging ranges (19–43 years old) and one case was reported from an 8-year-old L. amazonensis-infected patient (Table 5).

Co-morbidity/co-infection

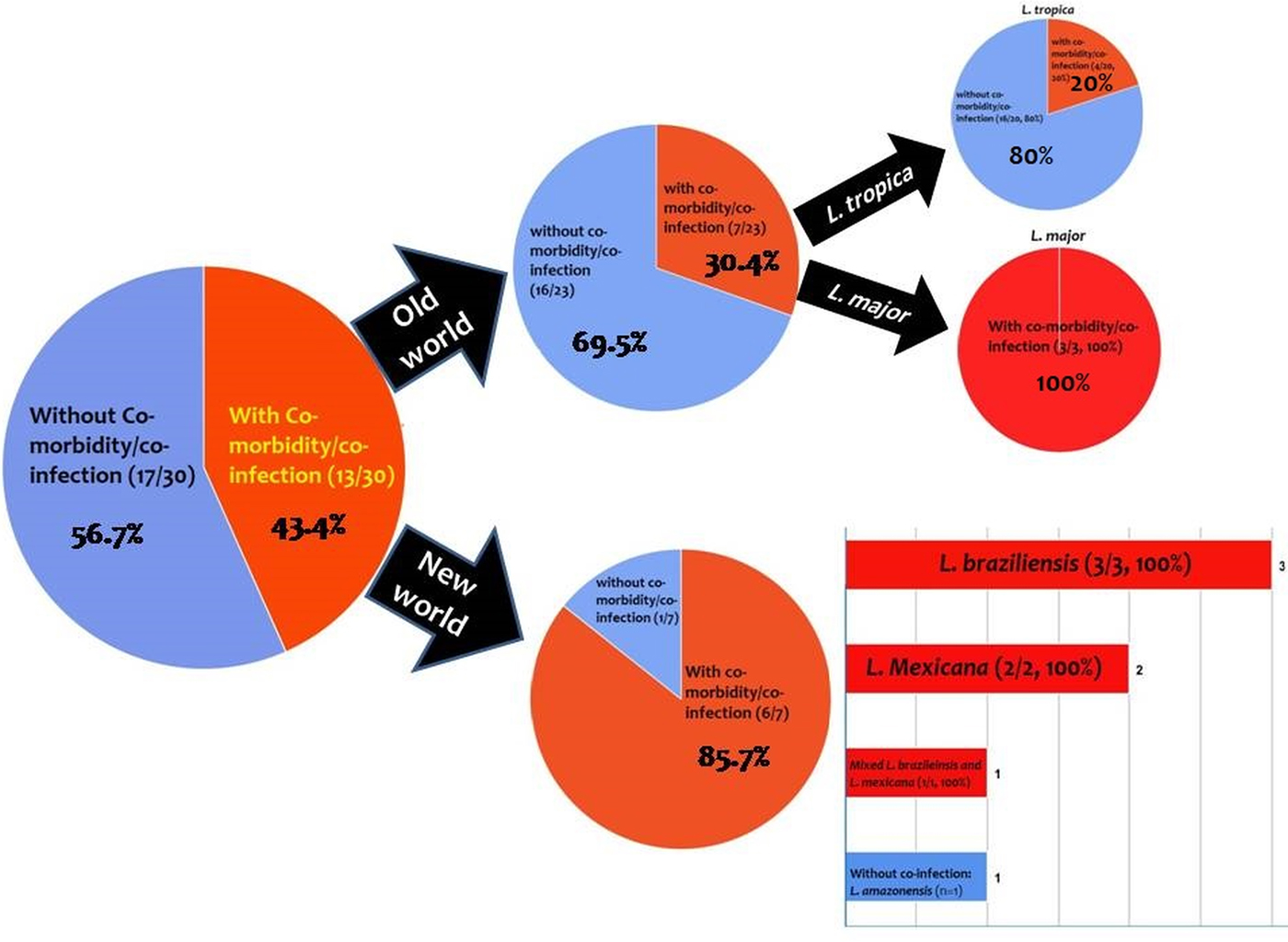

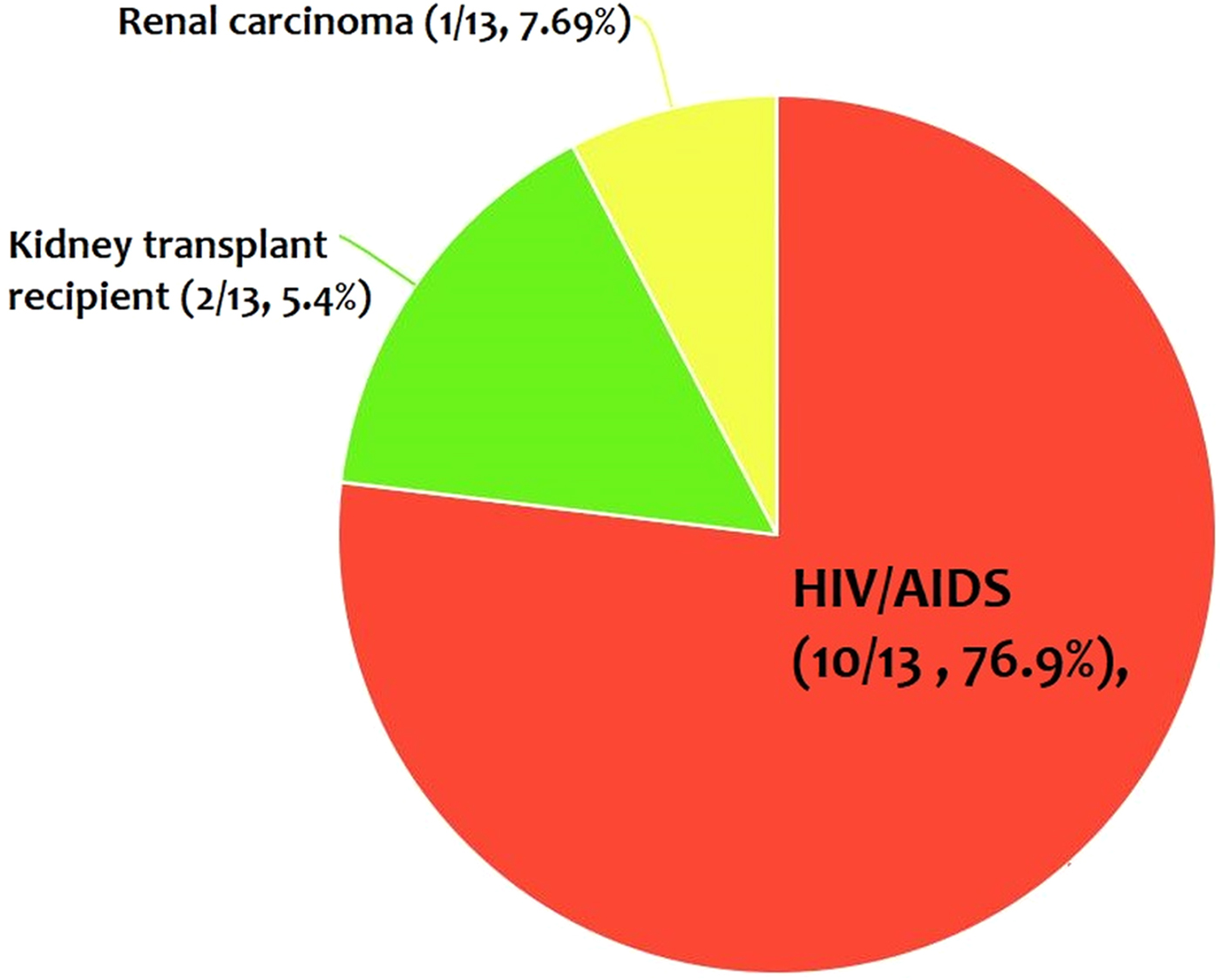

From the 30 cases, 13 (43.4%) patients had co-morbidity or co-infection (Fig. 4 and Tables 3–5). The highest co-morbidity/co-infection rate was reported from patients who infected by the new world Leishmania species (six out of seven cases, 85.7%). While seven out of 20 (35%) cases who infected by the new world Leishmania species had co-morbidity/co-infection. The most co-morbidity/co-infection was HIV/AIDS (10 out of 13 cases, 76.9%), kidney transplant recipient (two out of 13 cases, 15.4%) and renal carcinoma (one out of 13 cases, 7.69%) (Fig. 5). In patients with the new world Leishmania species infection, all three cases of L. braziliensis had co-morbidity/co-infection and were reported from a kidney transplant recipient (Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo2002), an HIV-positive patient (Silva et al. Reference Silva2002) and an HIV-positive patient with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis and pleuro-pericardial tuberculosis (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993, Reference Hernández1995a) (Table 5). Two cases of L. mexicana were reported from a CMV-positive kidney transplant recipient (Mestra et al. Reference Mestra2011) and an HIV-positive patient with P. carinii pneumonia (Ramos-Santos et al. Reference Ramos-Santos2000) (Table 5). Also, the patient with mixed L. brazileinsis and L. mexicana infection was HIV positive (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993, Reference Hernández1995a) (Table 5).

Fig. 4. Prevalence of co-infection/co-morbidity among the cases. Red: with co-infection/co-morbidity and blue: without co-infection/co-morbidity.

Fig. 5. The most co-infection/co-morbidity among the cases.

Co-morbidity/co-infection was reported from 20% (4/20) of L. tropica-infected patients (Fig. 5 and Table 3). Leishmania tropica was reported from one patient with HIV (Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010), one patient with HIV–TB–HCV (Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010) and one patient with renal carcinoma (Magill et al. Reference Magill1993). All of the three cases of L. major were reported from HIV-positive patients (Table 5) (Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007; Barro-Traore et al. Reference Barro-Traore2008; Shafiei et al. Reference Shafiei2014).

Main clinical manifestations

In most of the patients, there were major symptoms of VL including fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, anaemia and leucopenia, but some patients had non-specific symptoms such as malaise, headache, cough or no symptoms (Tables 3–5). However, it seems that complication of the disease might be involved in the immunity of the patients so that more severe infections alongside with more non-specific symptoms had reported from patients with co-infection/co-morbidity. Duration of the disease is ambiguous because it not reported in the most of the cases. In addition, some cases had several co-morbidity/co-infection that might impact on the duration of infection (Tables 3–5).

Cutaneous lesions were reported in nine out of 30 cases (30.0%), among them, seven and one patients infected with old and new world Leishmania species, respectively. In patients who infected with the old world Leishmania species, cutaneous lesions were detected in five out of 20 patients with L. tropica infection (two patients had co-infection with HIV/AIDS) and (Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi2008; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss2009; Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010; Mohebali et al. Reference Mohebali2011), two out of three L. major-infected patients (both cases had co-infection with HIV/AIDS) (Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007; Barro-Traore et al. Reference Barro-Traore2008). Among the patients with the new world Leishmania species infection, cutaneous lesions were reported in two cases of L. braziliensis infection who was a kidney transplant recipient patient (Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo2002) and an HIV-positive patient (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993, Reference Hernández1995a) (Tables 3–5).

Diagnostic tests

Diagnosis of the infection was conducted by one or more diagnostic tests according to the symptoms of the patients (Tables 3–5).

Treatment

Patients had mainly been treated with antimonial compounds so that the disease symptoms improved and liver and spleen size decreased or returned to normal size after treatment among the majority of the cases (Tables 3–5). However, five patients with L. tropica (Mebrahtu et al. Reference Mebrahtu1989; Magill et al. Reference Magill1993; Sacks et al. Reference Sacks1995; Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi2008) and one patient with L. major (Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007) showed refractory to antimonial compounds and treated with other drugs (such as amphotericin B, pentamidine, miltefosine, etc.) (Tables 3 and 4). Also, one patient with L. tropica was resistant to amphotericin B (Alborzi et al. Reference Alborzi2008) (Table 3). Some HIV-positive patients had also been received anti-retroviral therapy (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1993 Reference Hernández1995a; Magill et al. Reference Magill1993; Ramos-Santos et al. Reference Ramos-Santos2000; Silva et al. Reference Silva2002; Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2007; Barro-Traore et al. Reference Barro-Traore2008; Jafari et al. Reference Jafari2010; Shafiei et al. Reference Shafiei2014) (Tables 3 and 5).

Outcome

Although most of the patients had healed following common anti-leishmanial therapy alone or in combination with other drugs (Tables 3–5), mortality had occurred in two kidney transplant recipients that infected with L. braziliensis (Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo2002) and L. Mexicana (Mestra et al. Reference Mestra2011) and one HIV-positive patient with mixed L. brazileinsis and L. mexicana infection (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández1995b) (Table 5).

Discussion

Viscerotropic leishmaniasis is an interstitial form of leishmaniasis with some non-specific symptoms. These non-specific symptoms may be considered in endemic regions of CL, and also in immunocompromised patients to help differential diagnosis from other endemic diseases. CL is more distributed than VL worldwide, while the most cases of CL have been reported from Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Brazil, Iran, Syria, Ethiopia, North Sudan, Costa Rica and Peru.

The results revealed that the main causative agent of viscerotropic leishmaniasis is L. tropica. In some regions, such as east and southeast of Iran (Sharifi et al. Reference Sharifi2015; Karamian et al. Reference Karamian2016), Herat in Afghanistan (Mosawi and Dalimi, Reference Mosawi and Dalimi2016) and northwestern Pakistan (Khan et al. Reference Khan2016), L. tropica is the predominant Leishmania species. In these regions, the viscerotropic manifestations of L. tropica should be considered more seriously.

Studies have shown that co-infection of leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS is an important public health problem in different parts of the world (World Health Organization 2000; Monge-Maillo et al. Reference Monge-Maillo2014; Singh, Reference Singh2014) as well as Iran (Shafiei et al. Reference Shafiei2014). Co-morbidity with these two pathogens leads to rapid progression of the disease, development of more severe disease and a poor response to treatment (Singh, Reference Singh2014). Several atypical presentations have been reported from of CL patients, which most of them detected from HIV-infected individuals (Meireles et al. Reference Meireles2017). The results have shown that the majority of patients who infected with the new world Leishmania species and L. major had co-infection/co-morbidity such as HIV/AIDS (Figs 3 and 4). Therefore, viscerotropic leishmaniasis should be considered in patients with immunocompromising conditions.

Several studies have shown that higher prevalence of VL in male than female individuals (Guerin et al. Reference Guerin2002; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez2018), while a similar proportion in males and females had reported from CL patients (Karimkhani et al. Reference Karimkhani2016). We also found that higher prevalence of viscerotropic leishmaniasis in male than female cases (80% vs 167%). It is well documented that VL due to L. donovani infects all age groups, whereas L. infantum infects mostly children and immunosuppressed individuals (Chappuis et al. Reference Chappuis2007). Also the majority of cases of American VL caused by L. chagasi occur in children (Evans et al. Reference Evans1992; Pearson and de Queiroz Sousa, Reference Pearson and de Queiroz Sousa1996; D'Oliveira Júnior et al. Reference D'Oliveira Júnior1997). The results showed that the majority of the cases of viscerotropic leishmaniasis due to L. major and new world Leishmania species were reported from adults. In L. tropica, seven out of 20 cases were reported in patients under 15 years and the remaining cases were reported in adults (Table 3).

In conclusion, the results provide information regarding the species and clinical spectrum of viscerotropic leishmaniasis. Therefore, viscerotropic manifestations of CL in native people who live in endemic regions of CL should be considered for exact discrimination from other endemic infectious diseases. In patients who infected with L. tropica, a viscerotropic form of leishmaniasis should be more attended. Furthermore, viscerotropic leishmaniasis in patients with immunocompromising conditions and in non-native people who travel to the endemic regions of CL should be a greater consideration.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all researchers that their works were used in this review.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This manuscript is a review article and does not involve a research protocol for human and/or animal experimentation requiring approval by the relevant institutional review board or ethics committee.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/pao.2018.9