Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of asylum seekers and refugees worldwide, largely accounted for by refugees fleeing from the war in Syria to its neighbouring countries and Europe (UNHCR, 2018). Common mental disorders are prevalent in refugees, with estimated prevalence rates of 30.8% for depression and 30.6% for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009). Recent studies among Syrian refugees specifically also report elevated levels of distress (Tinghög et al., Reference Tinghög, Malm, Arwidson, Sigvardsdotter, Lundin and Saboonchi2017; Poole et al., Reference Poole, Hedt-Gauthier, Liao, Raymond and Bärnighausen2018).

Refugees are individuals who are ‘unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted’ (UN General Assembly, 1951). The steep increase in refugees carries significant public health implications (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016). Since the outbreak of the Syrian war, there has been an increase in studies evaluating mental health and psychosocial support programmes for Syrian refugees in Europe (e.g. Lehnung et al., Reference Lehnung, Shapiro, Schreiber and Hofmann2017) and the Middle East (e.g. Weinstein et al., Reference Weinstein, Khabbaz and Legate2016). Meta-analytic evidence supports cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and narrative exposure therapy to treat PTSD in refugees (Nosè et al., Reference Nosè, Ballette, Bighelli, Turrini, Purgato, Tol, Priebe and Barbui2017; Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Ballette, Nosè, Ostuzzi and Barbui2017). Although high-income countries such as the Netherlands have specialised mental health staff and programmes available for refugees, the treatment gap is large. Studies among refugees/migrants found that a large proportion did not receive adequate mental health care (Lamkaddem et al., Reference Lamkaddem, Stronks, Devillé, Olff, Gerritsen and Essink-Bot2014; Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016). Access to specialist mental health care is hampered by various barriers such as long waitlists, communication difficulties and stigma (Satinsky et al., Reference Satinsky, Fuhr, Woodward, Sondorp and Roberts2019).

To overcome barriers to mental health care for communities affected by adversity, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed Problem Management Plus (PM+). PM+ is a brief, transdiagnostic psychological intervention targeting symptoms of depression, anxiety and distress, and is based on CBT and problem-solving therapy strategies (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). The intervention comprises five face-to-face sessions with a non-specialist helper (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on individual PM+ in violence-affected communities in Pakistan and Kenya showed that participants who received individual PM+ had fewer symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD, higher levels of functioning and fewer self-identified problems (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017). Another RCT on group PM+ in distressed females in the Swat area in Pakistan showed similar results (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019).

In this study, we conducted a pilot RCT to (1) test trial procedures in advance of the definitive RCT; (2) evaluate acceptability and feasibility; and (3) gain a preliminary understanding about the likely effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PM+ among Syrian refugees with elevated levels of psychological distress in the Netherlands.

Methods

Setting

The study was carried out by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU) in collaboration with Stichting Nieuw Thuis Rotterdam (SNTR), a non-governmental organization (NGO) providing support with integration, including housing, Dutch language courses and guidance to work to approximately 200 Syrian refugee families with resident status in Rotterdam. The trial was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee at VU Medical Center, the Netherlands (Protocol ID: NL61361.029.17, 7 September 2017) and prospectively registered online (https://www.trialregister.nl/trial/6665).

Study design and participants

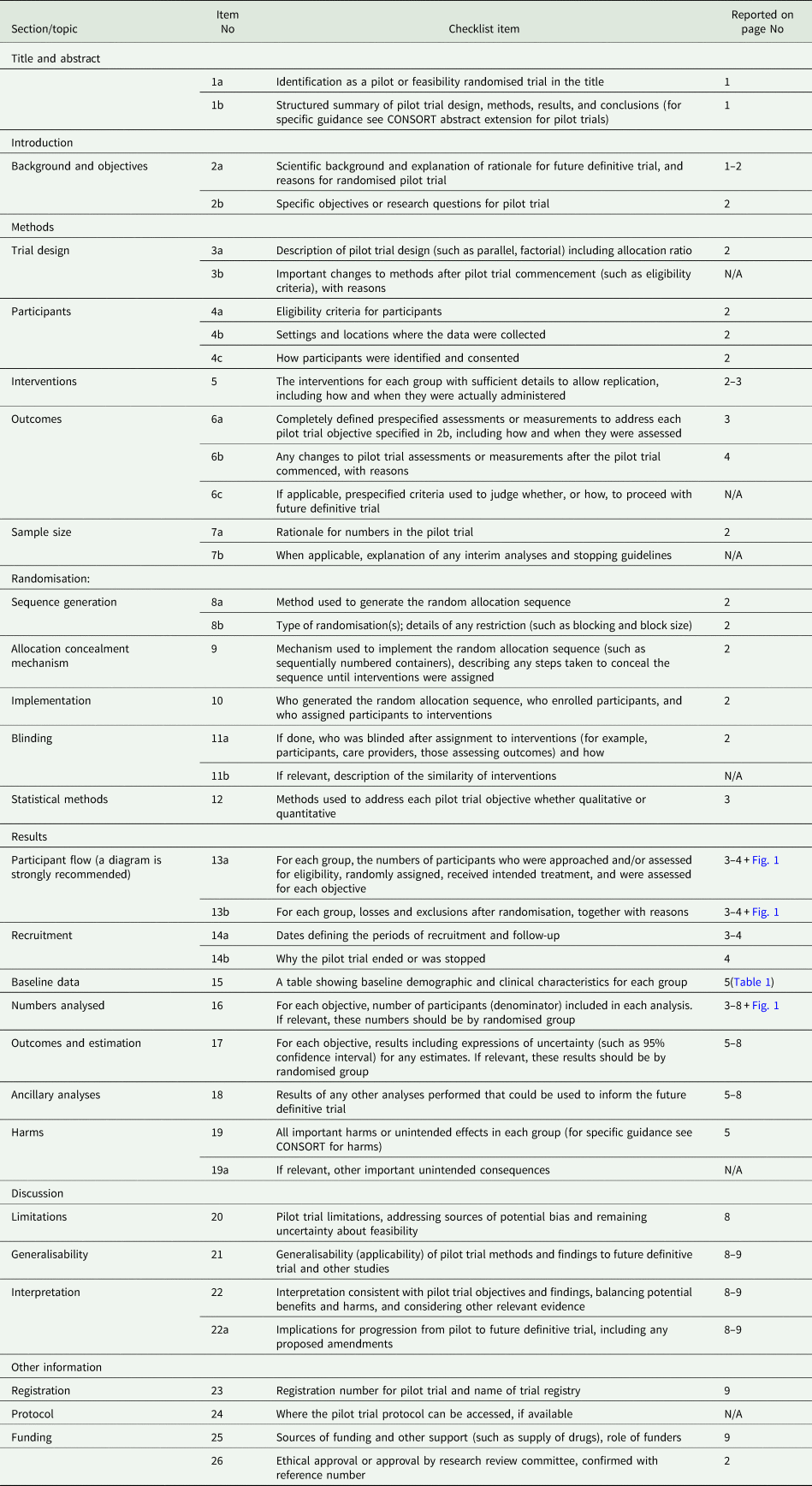

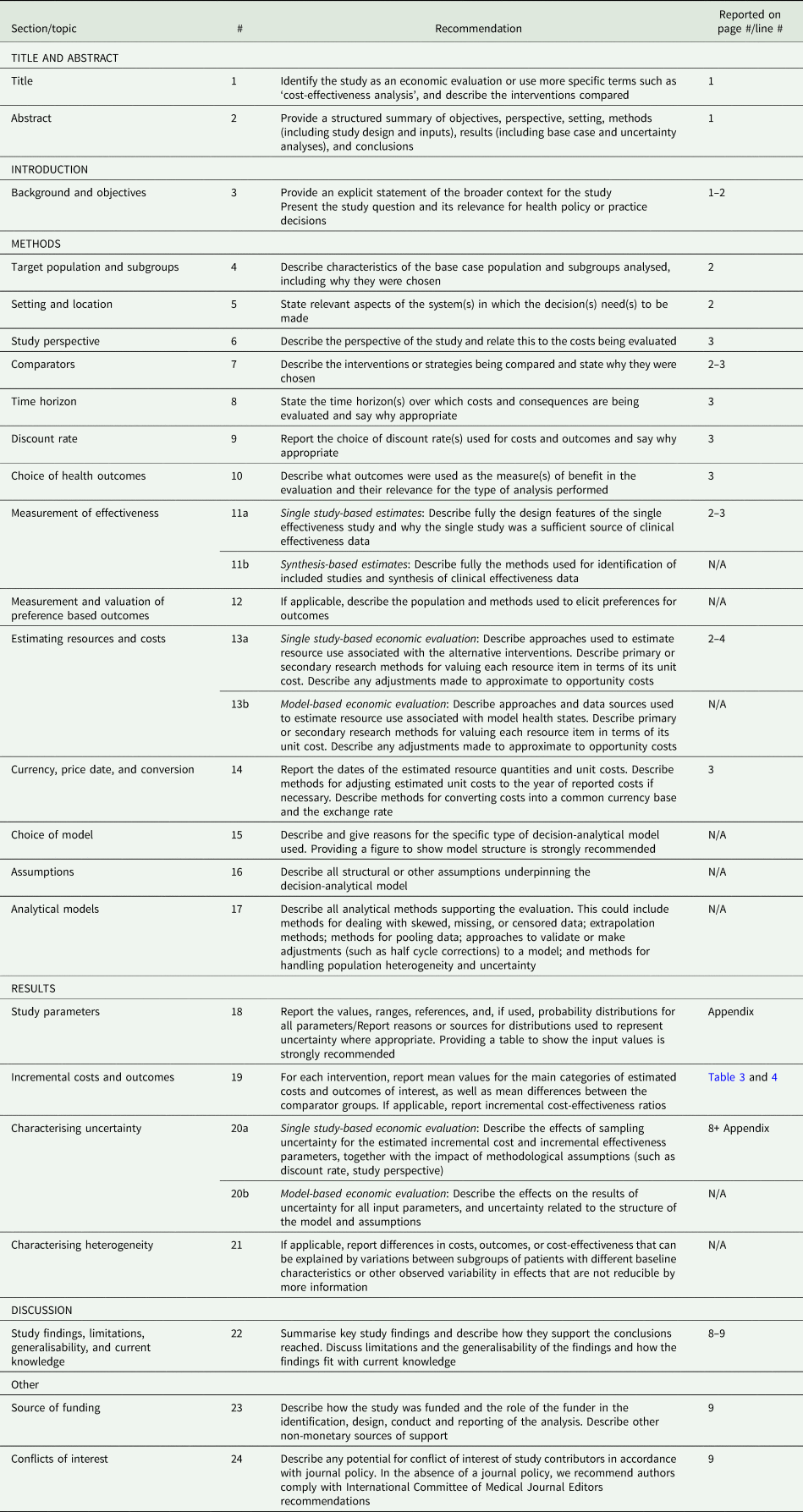

A single-blind pilot RCT using mixed-methods was conducted from April 2018 to May 2019. The study is part of the larger EU H2020-funded STRENGTHS project, which aims to scale-up brief, psychological interventions among Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East (Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Acarturk, Bird, Bryant, Burchert, Carswell, de Jong, Dinesen, Dawson, El Chammay, van Ittersum, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Miller, Morina, Park, Roberts, van Son, Sondorp, Pfaltz, Ruttenberg, Schick, Schnyder, van Ommeren, Ventevogel, Weissbecker, Weitz, Wiedemann, Whitney and Cuijpers2017). CONSORT and CHEERS reporting checklists (Husereau et al., Reference Husereau, Drummond, Petrou, Carswell, Moher, Greenberg, Augustovski, Briggs, Mauskopf and Loder2013; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Chan, Campbell, Bond, Hopewell, Thabane and Lancaster2016) are appended (Checklist A1 and A2).

Adult Arabic-speaking Syrian refugees (18 years or above) were recruited during language classes and individual home visits by SNTR staff. Inclusion criteria were elevated levels of psychological distress as indicated by a score >15 on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002) and impaired daily functioning, indicated by a score >16 on the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0; Ustun et al., Reference Ustun, Kostanjesek, Chatterji, Rehm, Üstün, Kostanjsek, Chatterji and Rehm2010). Exclusion criteria were acute medical conditions, imminent suicide risk (assessed with the PM+ manual suicidal thoughts interview) (WHO, 2016), expressed acute needs or protection risks, indications of severe mental disorders (e.g. psychotic disorders) or cognitive impairment (e.g. severe intellectual disability; assessed by the PM+ manual observation checklist) (WHO, 2016).

Procedures

Oral and written informed consent (IC) was obtained from all participants before screening. Included participants completed baseline assessment questionnaires and were randomised into PM+/care as usual (CAU) or CAU alone by an independent researcher not involved in the study. CAU comprises all other mental health services available to Syrian refugees in the Netherlands (e.g. community services and non-directive counselling by local NGOs, or referral to specialised PTSD treatment such as narrative exposure therapy). Randomization with block size 6 was performed using software on a 1:1 basis. Participants were phoned on group allocation by an Arabic-speaking team member not involved in assessments. Participants randomised to PM+/CAU were directly contacted by their helper to plan the first session within 1 week after baseline assessment.

Post- and 3-month follow-up assessments were scheduled 1 week after the 5th PM+ session (or 6 weeks after baseline) and 3 months after the 5th PM+ session. Assessments were carried out by two Arabic-speaking assessors who received a 3-day training on questionnaire administration, general interview techniques, common mental disorders, psychological first aid and ethical research conduct. Assessors were blinded to condition and indicated after each post- and follow-up assessment whether group allocation was disclosed to them (i.e. yes PM+/CAU; yes CAU; no).

Problem Management Plus (PM+)

The PM+ intervention has five 90 min sessions, delivered weekly. Four components are introduced by the helper, including a slow breathing exercise, problem-solving strategy, behavioural activation through re-engaging with pleasant and task-oriented activities, and accessing social support. A detailed description of PM+ is available (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). The PM+ manual was translated/culturally adapted for use among Syrian refugees through qualitative study (cf. Applied Mental Health Research Group, 2013) and by using a framework for the cultural adaptation of psychological interventions (Bernal and Sáez-Santiago, Reference Bernal and Sáez-Santiago2006; see de Graaff et al., Reference de Graaff, Cuijpers, Acarturk, Bryant, Burchert, Fuhr, Huizink, Jong, Kieft, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Morina, Park, Uppendahl, Ventevogel, Whitney, Wiedemann, Woodward and Sijbrandij2020).

The intervention was delivered by eight Arabic-speaking Syrian non-specialist helpers already working as ‘connectors’ at SNTR. They received 8 days of training followed by weekly face-to-face group supervision by PM+ trainers/supervisors throughout the trial. Training involved education about common mental disorders, basic counselling skills, delivery of intervention strategies and self-care (WHO, 2016). Supervision included discussion of individual cases and difficulties experienced by helpers, practice of skills and self-care (WHO, 2016). Helpers had at least high school education, a background in social work, teaching or another related field, and sufficient Dutch or English speaking ability. Trainers/supervisors were mental health care professionals who underwent 5-day training covering elements of the training of helpers, as well as training and supervision skills (cf. Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016).

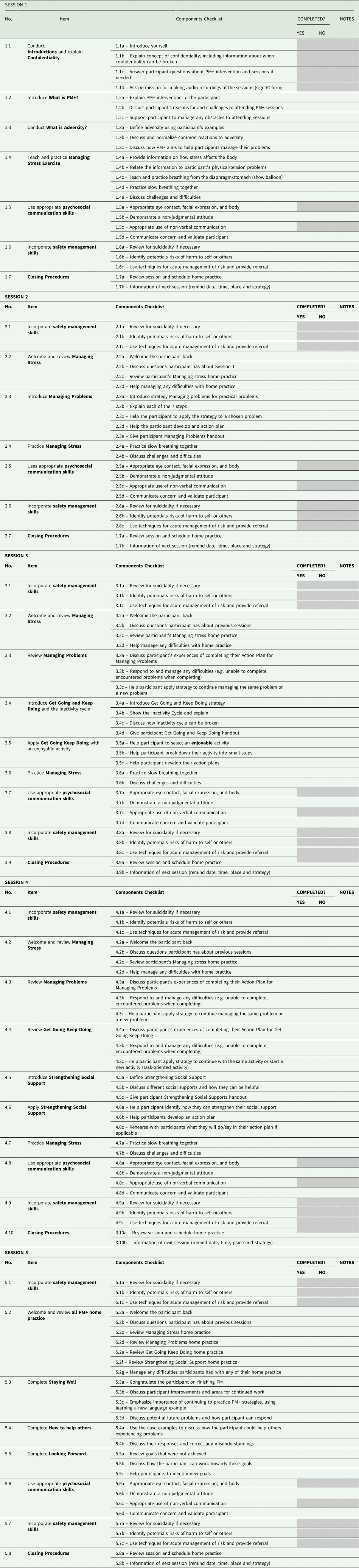

A 25% random sample of the audio recordings was independently coded by two research assistants for adequate delivery of PM+ treatment elements (yes/no) through a checklist addressing requisite PM+ components per session (see appended Checklist A3).

Primary outcome measure

Symptoms of anxiety and depression. The 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) (Arabic version) (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth and Covi1974; Selmo et al., Reference Selmo, Koch, Brand, Wagner and Knaevelsrud2016) was used to measure symptoms of anxiety (10 items) and depression (15 items). Item mean scores (range 1–4) were analysed.

Secondary outcome measures

Functional impairment. The WHODAS 2.0 is a well-accepted, validated 12-item instrument to assess health and disability (Ustun et al., Reference Ustun, Kostanjesek, Chatterji, Rehm, Üstün, Kostanjsek, Chatterji and Rehm2010). Items are rated on a 1–5 scale (range 12–60).

Posttraumatic stress symptoms. The Arabic version of the 20-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al., Reference Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte and Domino2015; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Ertl, Catani, Ismail and Neuner2018) assesses PTSD symptoms on a 0–4 scale (range 0–80).

Self-identified problems. The Psychological Outcomes Profiles (PSYCHLOPS) (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Shepher, Christey, Matthews, Wright, Parmentier, Robinson and Godfrey2004) questionnaire is a patient-generated indicator of change after therapy. It covers self-identified problems and function (both free-text fields), and wellbeing scored on a 0–5 scale (range 0–20).

Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). The CSRI (Beecham and Knapp, Reference Beecham, Knapp, Thornicroft, Brewin and Wing1992) was modified for use in Syrian refugees in the Netherlands to self-report health service utilization, receipt of informal family care and participation in employment/education or other productive use of time over 3 months.

Other measures

Trauma exposure. Life-time traumatic experiences were measured through a 27-item checklist (Schick et al., Reference Schick, Zumwald, Knopfli, Nickerson, Bryant, Schnyder, Muller and Morina2016) adapted for this project. Items were scored 1 (yes) or 0 (no), total range 0–27.

Post-migration stressors. The Post-Migration Living Difficulties checklist (Arabic version) (Silove et al., Reference Silove, Sinnerbrink, Field, Manicavasagar and Steel1997; Schick et al., Reference Schick, Zumwald, Knopfli, Nickerson, Bryant, Schnyder, Muller and Morina2016) assesses 17 post-migration challenges scored on a 0–4 scale. Items with at least a score of 2 (moderately serious problem) were considered positive responses and summed for analysis (range 0–17).

These measures were used for descriptive analyses.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses

To compare reductions in primary/secondary outcomes between groups across three time points in the intention-to-treat sample (N = 60), we used linear mixed models in RStudio version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2018). This method allows the number of observations to vary between participants and handles missing outcome data. The mixed model uses a longitudinal data structure that includes both fixed and random effects. Time (categorical), group (PM+/CAU v. CAU) and interactions between group and time were included as fixed effects in mixed models together with a random intercept and random time effect. Differences in least-squares means (intervention effects) at each time point with 95% confidence intervals were derived. Cohen's d for the effect of the intervention was estimated by calculating the difference between estimated means (corrected for baseline) divided by raw pooled standard deviation. A two-sided p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. As this study's primary intention was to test feasibility and acceptability, it was not powered to detect significant differences.

The reliable change index was used to evaluate whether participants have reliable and clinically significant change scores from baseline to post- and follow-up (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991).

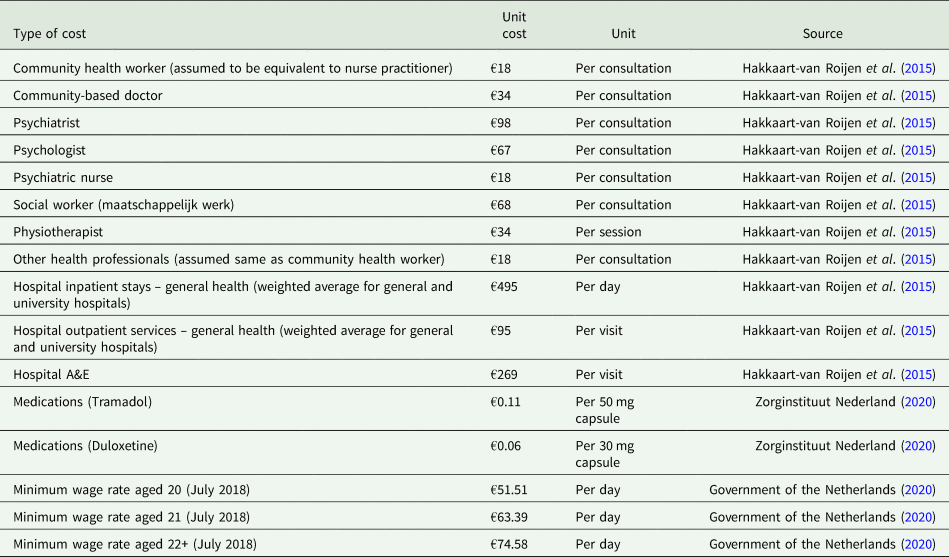

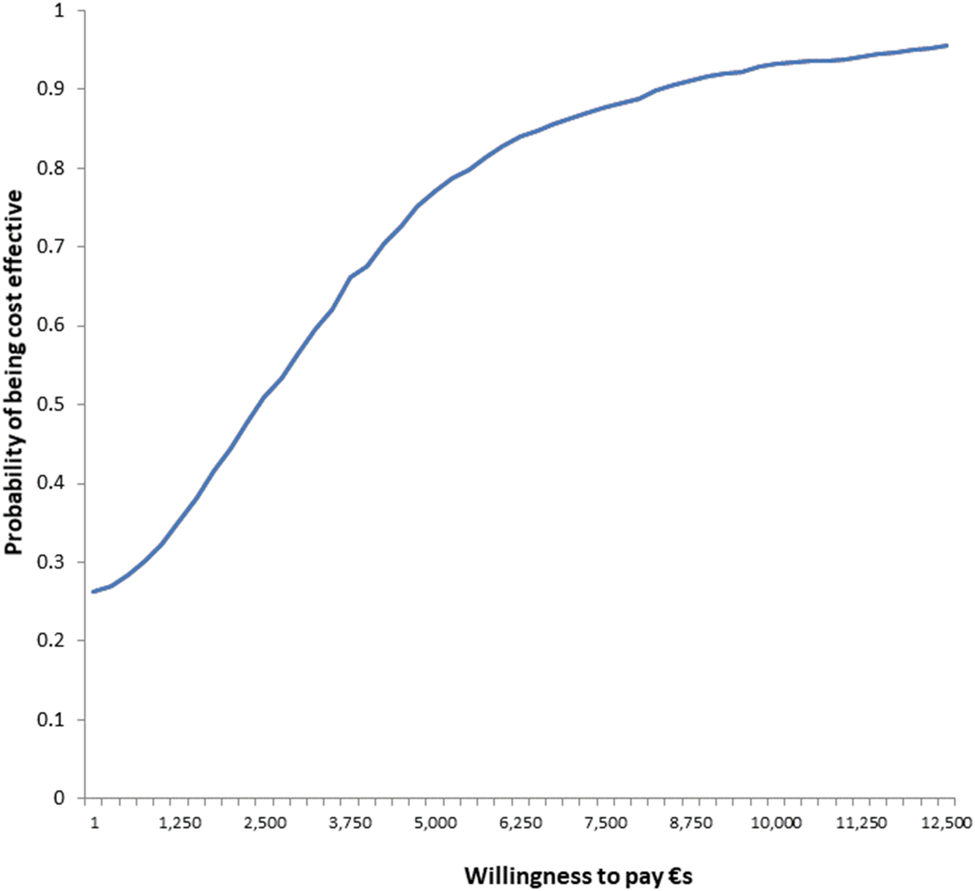

The economic analysis was performed from both a healthcare system and a broader perspective, including productivity impacts on participants and their families. Health service utilization and productivity losses were estimated across all time points. PM+ training, supervision resource and delivery costs were obtained from project records. Unit costs were attached to health service utilization using published tariffs used in the Netherlands (Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., Reference Hakkaart-van Roijen, Van der Linden, Bouwmans, Kanters and Tan2015). Medication reimbursement rates were obtained from the Netherlands National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland, 2020). See Appendix Table A1 for unit costs used. All patient and family productivity losses were valued using age-specific 2018 minimum wage rates (Government of the Netherlands, 2020). All costs are 2018 euros and discounting was not applied given the short study duration. Given the skewed distribution of costs, differences in mean costs were compared between the two groups using bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping 1000 times. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) per additional recovery and improvement without recovery at 3-month follow-up were calculated. Statistical uncertainty was explored through bootstrapping 1000 randomly resampled pairs of costs and outcomes. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were generated to show the likelihood PM+ is cost-effective at different willingness to pay levels.

Semi-structured interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim in interview language (Arabic, Dutch or English). Arabic transcripts were translated into English by bi-lingual research assistants. Deidentified transcripts were analysed thematically and independently by two researchers (AdG and AW) in NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2015). Inductive analysis was used to categorise data and elicit themes. Findings were discussed by these researchers and a final coding framework agreed and then applied to all transcripts.

Results

Objective 1: testing trial procedures

Recruitment and consent rates

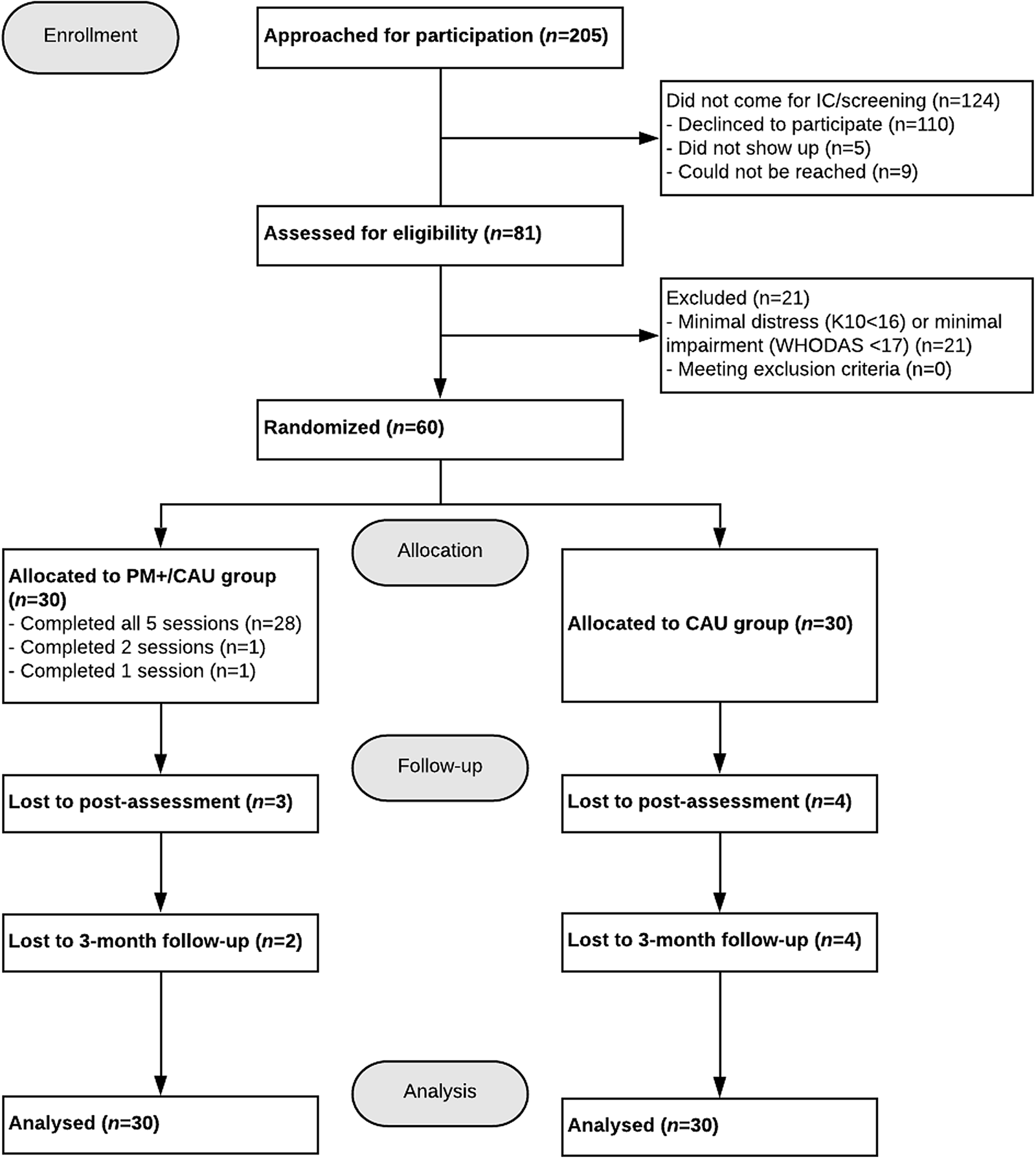

Recruitment occurred from April to November 2018. In total, 205 individuals gave permission to SNTR staff to be contacted by the VU research team. Of these, 110 declined, ten were unreachable and five did not attend screening. Eighty-one participants gave IC and were screened for eligibility to participate. Of these, 60 participants were included and randomised into PM+/CAU (n = 30) or CAU alone groups (n = 30). Figure 1 presents the CONSORT flow diagram.

Fig. 1. CONSORT flow-diagram.

Group allocation and blinding

An SNTR team-leader matched PM+ participants to helpers. During the trial, we decided to ask all participants at the screening interview whether they preferred matching with a male or female helper to facilitate the matching procedures; however, female helpers preferred not to be matched to male participants. Blinding was successful in 47% of outcome assessments.

Attendance and follow-up assessments

Assessments occurred between May 2018 and March 2019. Twenty-eight (93.3%) of the 30 participants allocated to PM+/CAU completed all five sessions. Two stopped after sessions 1 and 2 because the spouse did not allow participation and due to lack of time. Three months post-intervention, data were obtained from 54 participants, with 86.7% completing all assessments. Reported reasons for non-attendance across assessments were ‘prefers to withdraw’ (n = 3), ‘lack of time’ (n = 3), ‘abroad/unavailable’ (n = 1) and ‘no approval from spouse’ (n = 1). In 23% of outcome assessments, assessors assisted participants by reading questionnaires aloud.

PM+ protocol fidelity assessment

Fifty per cent (n = 15) of PM+/CAU participants agreed to have their sessions audiorecorded. Two research assistants scored 25% (n = 18 tapes) of 72 available audiorecorded sessions after five practice tapes scored by both research assistants (Cohen's κ = .80). Fidelity checks indicated helpers adhered to 76.6% of the PM+ protocol. Helpers completed 27 checklists, reporting 93.7% completion of the PM+ protocol.

Objective 2: experiences with PM+ and barriers to treatment

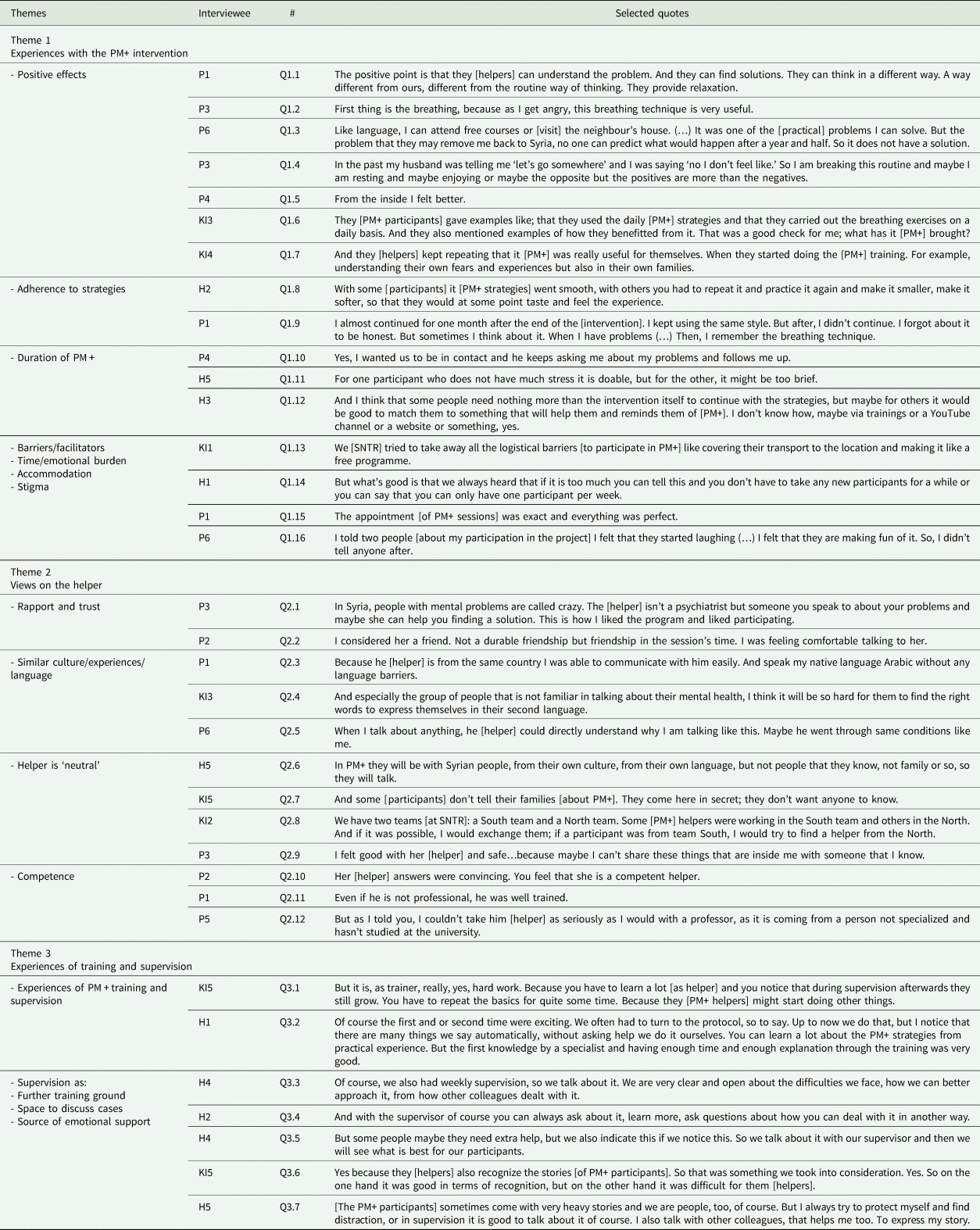

Semi-structured interviews with six PM+ participants, five helpers and five key informants explored experiences with PM+, acceptability and feasibility in addition to barriers and facilitators of PM+ implementation. Quotes (Q) are depicted in Appendix Table A2.

Experiences with the PM+ intervention

Interviewees spoke generally positively about the PM+ intervention (Q1.1) and strategies (Q1.2–3). Its therapeutic effect on participant mental health (Q1.5–6), as well as that of helpers (Q1.7), was the dominant reason for holding a positive view.

Helpers stressed breaking homework into small feasible steps would improve adherence (Q1.8). According to helpers, participants generally became more motivated and confident about the intervention after their first positive experience in applying a learned strategy. Some participants said they started to forget about strategies after completing PM+ (Q1.9), and several participants and helpers thought PM+ might be too brief (Q1.10–12).

Perceived facilitators of PM+ adherence were related to the accommodation of the programme for participants (e.g. travel expense coverage, flexibility scheduling sessions) and helpers (e.g. time reserved to conduct PM+ sessions and supervision during working hours, ability to decrease caseload) (Q1.13–15).

Overall, participants did not disclose their participation in PM+ for fear of gossip and ridicule (Q1.16). However, a few said they shared their PM+ experiences with family members and practised strategies with them. A challenge to intervention adherence was the ‘busy lives’ (H1) of some participants.

Views on the helper

Participants and helpers mentioned they quickly established rapport and trust and felt comfortable sharing their stories and problems (Q2.1). Two participants even called their helper a ‘friend’ (Q2.2).

All interviewees spoke about the importance of PM+ being in Arabic, as it facilitated communication and self-expression (Q2.3–4). Having a similar background was generally found supportive for building rapport, although it was mentioned that it could cause distrust. For example, one participant was initially apprehensive because the helper was Syrian but later found their shared experiences beneficial (Q2.5). Participants appreciated similarities with their helper, but also that the helper was otherwise a stranger (Q2.6–8), creating a confidential and safe environment (Q2.9).

Generally, participants perceived their helper as competent (Q2.10–11). One participant commented that if the helper was a professional, he may have benefitted more (Q2.12).

Information on experiences in training and supervision of helpers is provided in Appendix Table A2.

Objective 3: estimating likely effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Treatment effect

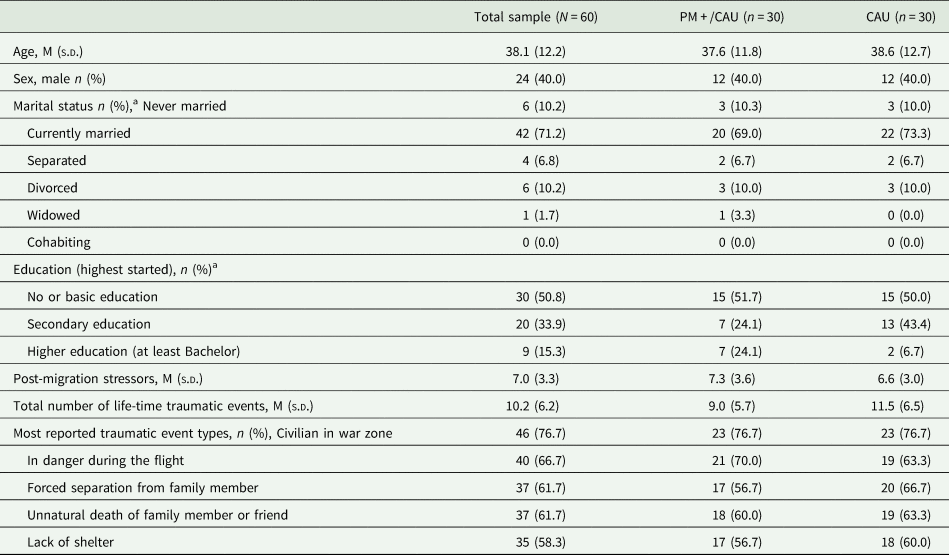

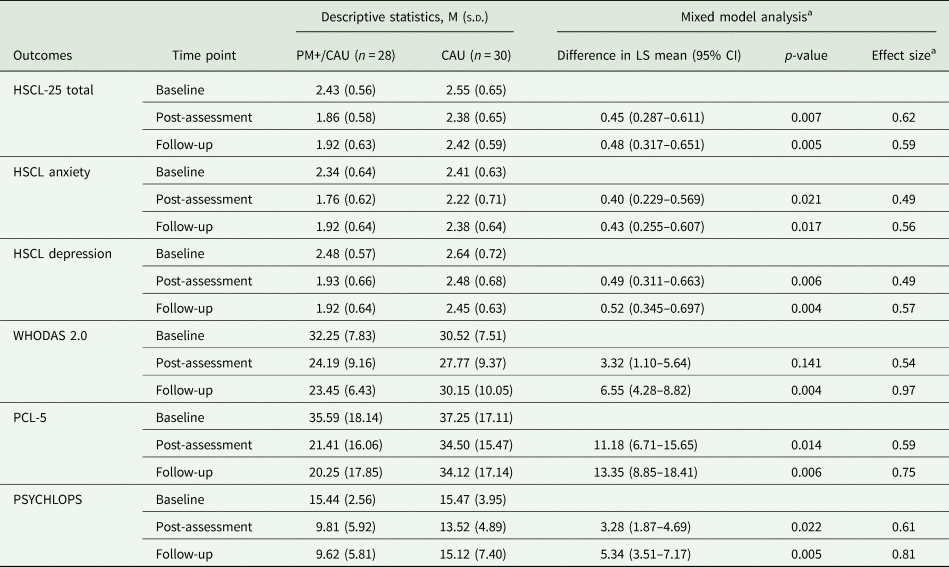

Two serious adverse events related to domestic violence were reported to the Research Ethics Review Committee. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics, traumatic events and post-migration stressors. Table 2 presents findings on primary outcomes of anxiety and depression (HSCL-25), and secondary outcomes of functional impairment (WHODAS 2.0), symptoms of PTSD (PCL-5) and self-identified problems (PSYCHLOPS) in PM+/CAU and CAU groups at all time points. There were no significant group differences between participants who were lost to follow-up v. those retained. The pattern of missing data is presented in Appendix Table A3.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

a Data not obtained for one PM+/CAU participant, valid per cent reported.

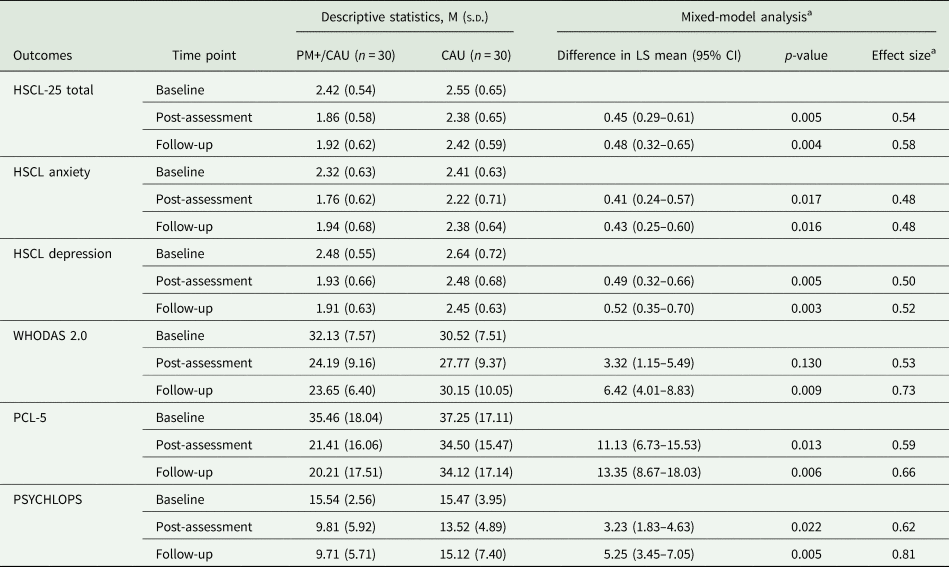

Table 2. Summary statistics and results from mixed-model analysis of primary and secondary outcomes

M, mean; s.d., standard deviation; LS mean, least-squares mean.

HSCL-25 = 25-item Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (range item-mean = 1–4, higher scores indicate elevated anxiety or depression); WHODAS 2.0 = WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (range 12–60, higher scores indicate worse functional impairment); PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (range 0–80, higher scores indicate greater severity); PSYCHLOPS = Psychological Outcomes Profiles (range 0–20, higher scores indicate poorer outcome).

a Effect sizes are determined by calculating the difference between the estimated means (corrected for baseline) divided by the raw pooled standard deviation.

Primary outcomes

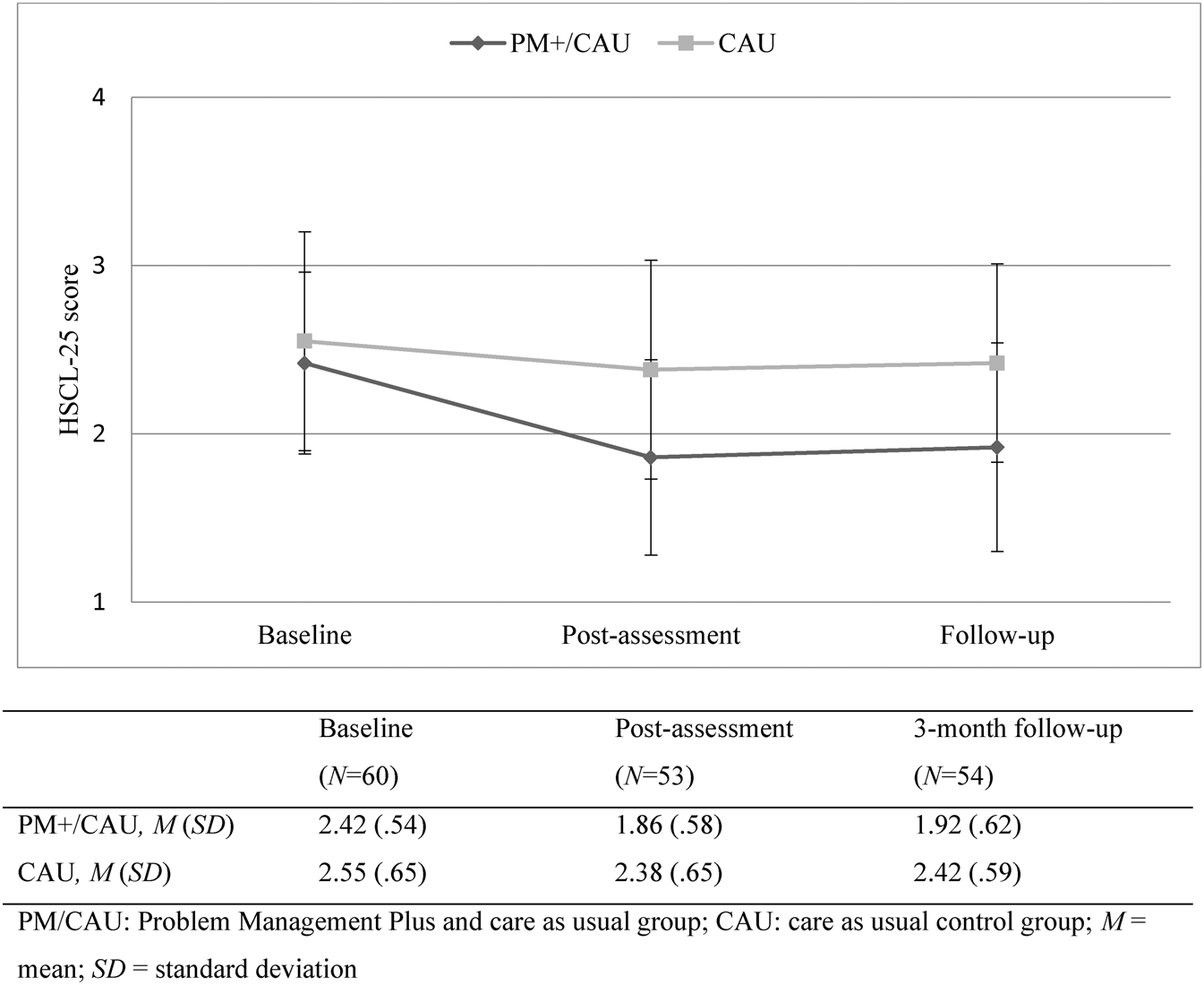

Linear mixed models in the intention-to-treat sample for the HSCL-25 total score showed a significant effect of time, moderated by condition (χ 2(2) = 10.41; p = 0.005). In the PM+/CAU group, overall HSCL-25 scores decreased relative to the CAU group (see Fig. 2). Post-hoc tests showed PM+/CAU relative to the CAU had lower scores 1 week (mean [standard deviation] 1.86 [0.58] v. 2.38 [0.65]; adjusted mean difference (AMD), 0.45; 95% CI 0.29–0.61, p = 0.005) and 3 months after the intervention (1.92 [0.62] v. 2.42 [0.59]; AMD 0.48; 95% CI 0.32–0.65, p = 0.004). Effects sizes were moderate to large (d = 0.54 and d = 0.58, respectively) (Table 2).

Fig. 2. HSCL-25 total score across time points.

For HSCL-25 anxiety, the effect of time was significant, and this was moderated by condition (χ 2(2) = 7.58; p = 0.022). In the PM+/CAU group, anxiety decreased relative to the CAU group. Post-hoc contrasts showed a medium effect post-assessment (1.76 [0.62] v. 2.22 [0.71]; AMD 0.41; 95% CI 0.24–0.57, p = 0.017, d = 0.48), and at 3-month follow-up (1.94 [0.68] v. 2.38 [0.64]; AMD 0.43; 95% CI 0.25–0.60, p = 0.016, d = 0.48).

We also found a significant effect of time for HSCL-25 depression, moderated by condition (χ 2(2) = 8.58; p = 0.013). In the PM+/CAU group, depression decreased relative to the CAU group. Post-hoc contrasts showed a medium effect post-assessment (1.93 [0.66] v. 2.48 [0.68]; AMD 0.49; 95% CI 0.32–0.66, p = 0.005, d = 0.50) and at 3-month follow-up (1.91 [0.63] v. 2.45 [0.63]; AMD 0.52; 95% CI 0.35–0.70, p = 0.003, d = 0.52).

Secondary outcomes

Linear mixed models furthermore showed a significant interaction effect in favour of PM+/CAU between time and condition for psychosocial functioning (WHODAS 2.0; χ 2(2) = 12.99; p = 0.001), symptoms of PTSD (PCL-5; χ 2(2) = 9.07; p = 0.010) and self-identified problems (PSYCHLOPS; χ 2(2) = 10.51; p = 0.005). Post-hoc contrasts at 3-month follow-up showed the PM+/CAU group relative to the CAU group had higher levels of psychosocial functioning (23.65 [6.40] v. 30.15 [10.05]; AMD 6.42; 95% CI 4.01–8.83, p = 0.009), and decreased scores for PTSD symptoms (20.21 [17.51] v. 34.12 [17.14]; AMD 13.35; 95% CI 8.67–18.03, p = 0.006) and self-identified problems (9.71 [5.71] v. 15.12 [7.40]; AMD 5.25; 95% CI 3.45–7.05, p = 0.005). Moderate to large effects were found (d = 0.73, d = 0.66, d = 0.81, respectively).

Analyses with PM+ completers only (n = 28) v. CAU (n = 30) indicated similar results (Appendix Table A4).

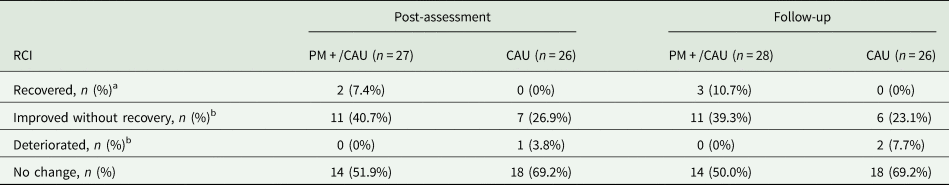

Reliable change index for symptoms of anxiety and depression

At 3-month follow-up, 14 PM+/CAU participants had a reliable change on HSCL-25 total score, of which three were clinically significant (i.e. recovered). In the CAU group, six participants had a reliable decrease in HSCL-25 scores, while two had a reliable increase in scores (i.e. deteriorated) (Appendix Table A5).

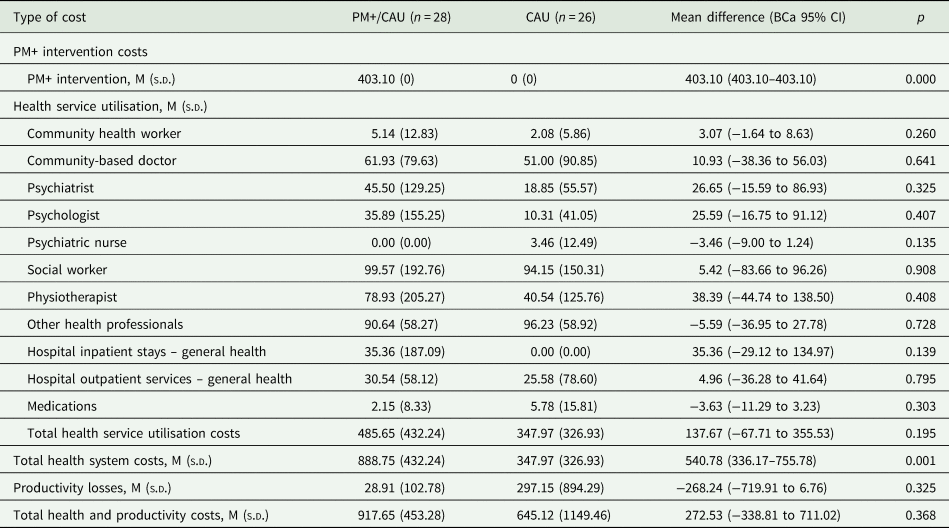

Economic analysis

At 3-month follow-up, mean costs per PM+/CAU participant were significantly higher than in CAU participants from a health service perspective (€888.75 [s.d. €432.24] v. €347.97 [326.93]; MD €540.78; 95% CI €336.17–€755.78, p = 0.001) (Table 3). Excluding PM+ training, supervision and delivery, costs remained non-significantly higher for PM+/CAU (€485.65 [€432.24] v. €347.97 [326.93]; MD €137.67; 95% CI €–67.71 to €355.53, p = 0.195).

Table 3. Mean health and productivity costs (2018 euros) per participant at 3-month follow-up

Productivity costs were non-significantly lower for PM+/CAU participants (€28.91 [102.78] v. €297.15 [894.29]; MD €268.24; 95% CI €–719.91 to €6.76, p = 0.325). Overall costs between PM+/CAU and CAU did not differ significantly (€917.65 [€453.28] v. €645.12 [1149.46]; MD €272.53; 95% CI €–338.81 to €711.02, p = 0.368).

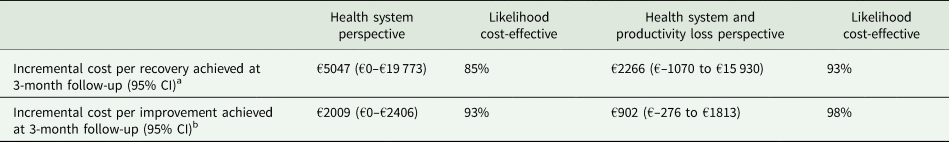

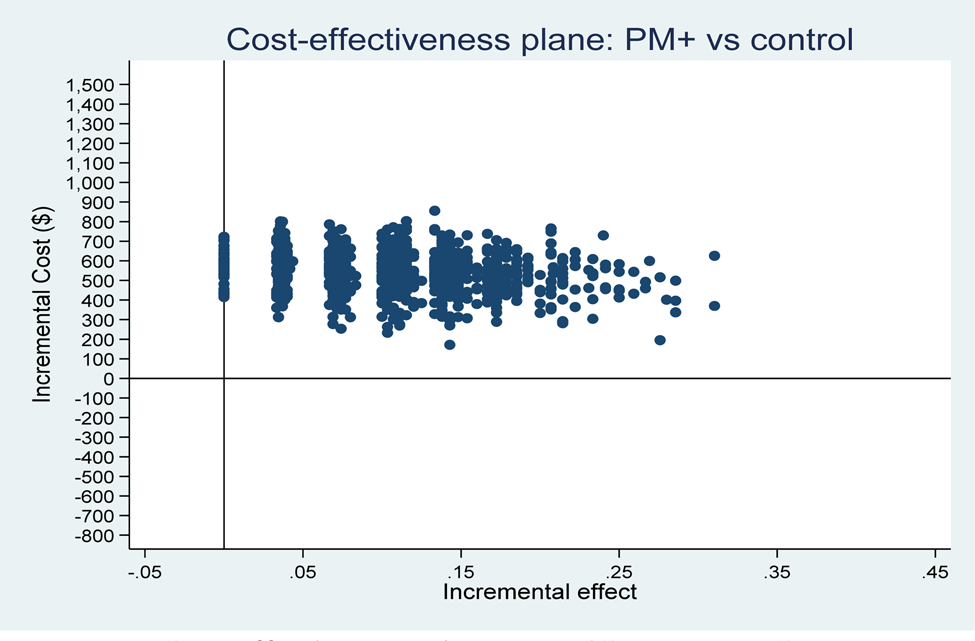

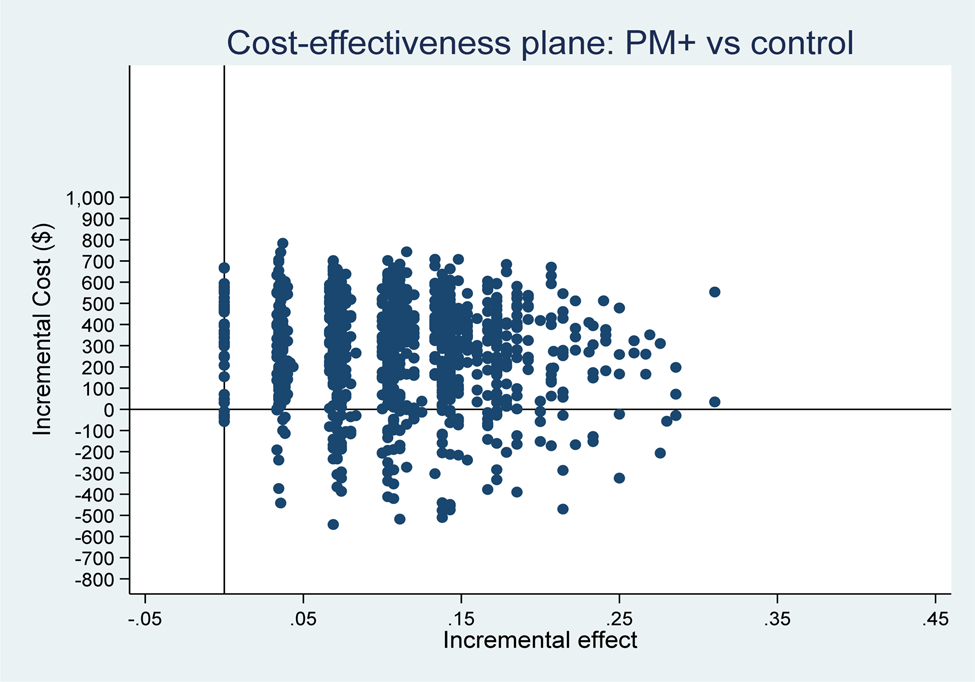

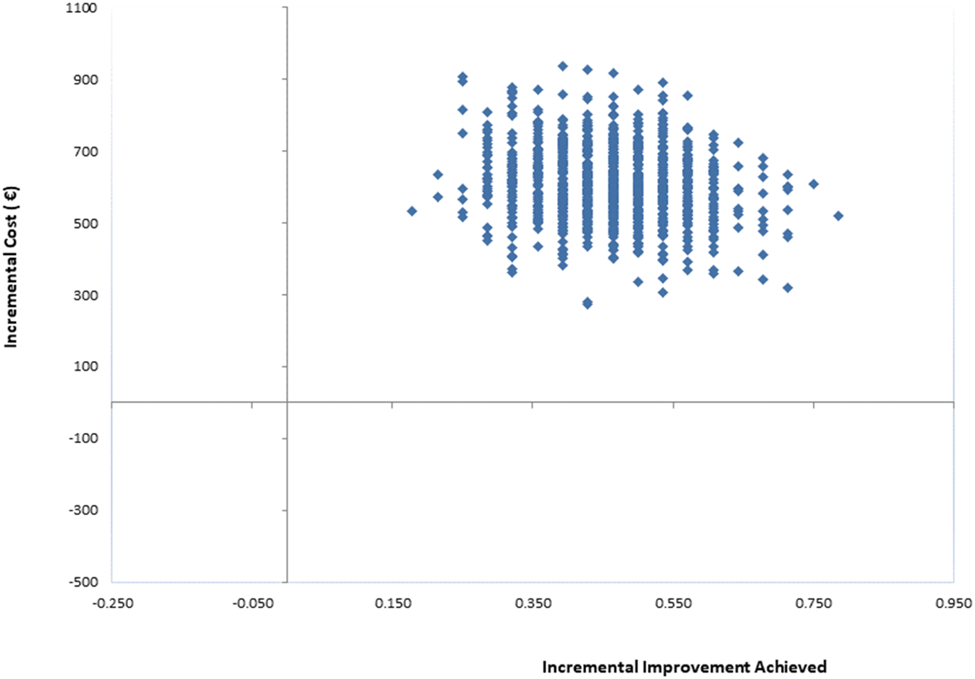

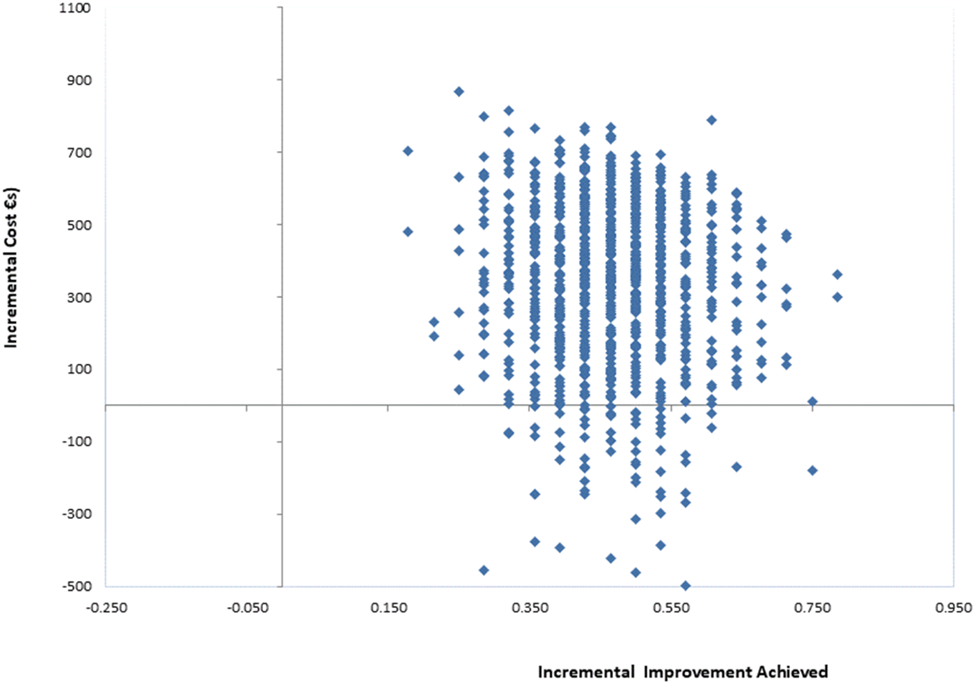

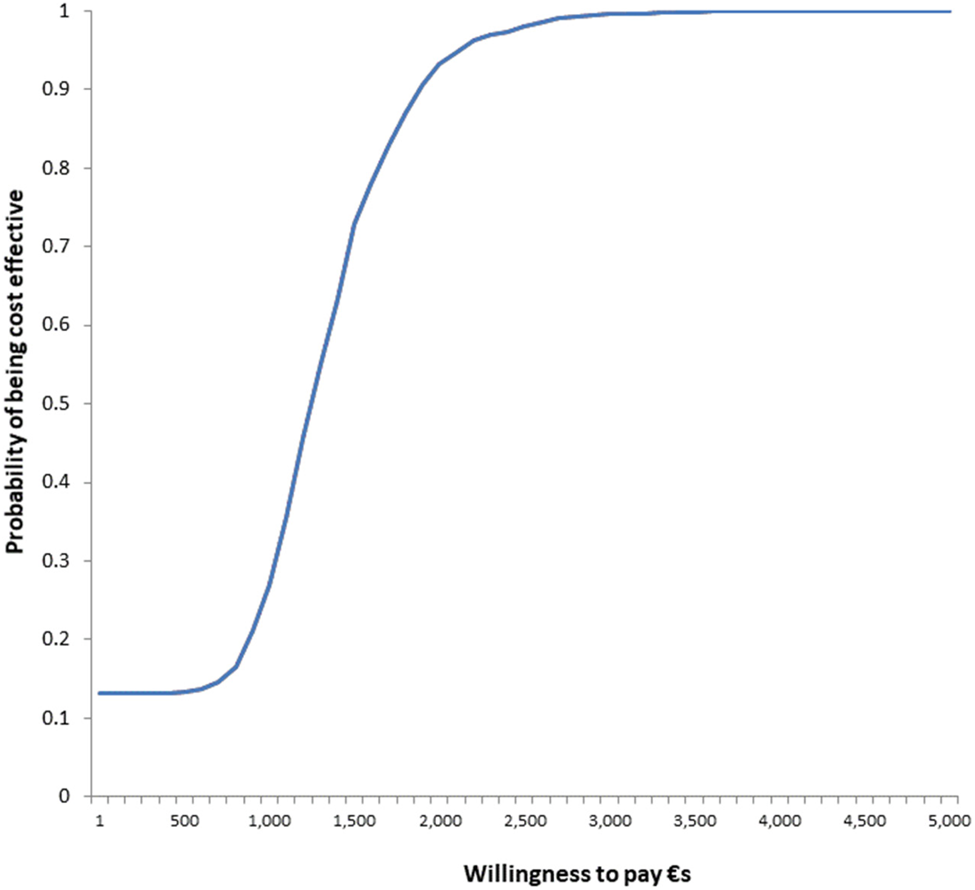

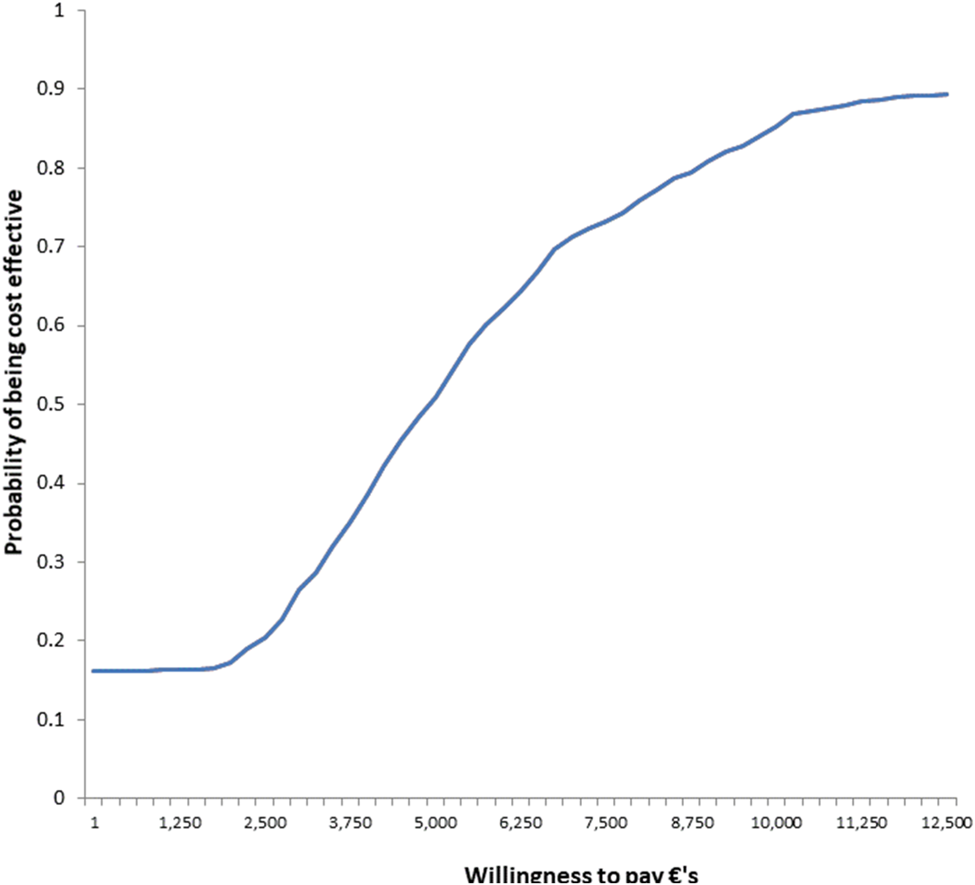

Table 4 summarises results of the exploratory cost-effectiveness analysis. From a health system perspective, PM+/CAU had an ICER of €5047 (95% CI €0–€19 773) per additional recovery achieved. This was €2266 (95% CI €–1070 to €15 930) when productivity losses averted were included. Cost-effectiveness planes in Figs A1-A2 (Appendix) indicate when productivity losses are considered PM+/CAU may even have both better outcomes and lower costs than CAU. The ICER per additional improvement on the HSCL-25 without recovery was €2009 (95% CI €0–€2406). Figs A3–A6 (Appendix) show cost-effectiveness planes and CEACs per additional improvement without recovery.

Table 4. Exploratory cost-effectiveness analyses (2018 euros)

a Assumes a willingness to pay of €10 000 per recovery on the HSCL-25 achieved.

b Assumes a willingness to pay of €2000 per significant improvement on the HSCL-25 achieved.

While no accepted cost-effectiveness threshold for recovery from depression and anxiety exists, CEAC indicate at least an 85% chance that PM+/CAU is cost-effective if funders are willing to pay €10 000 per recovery (Figs A7-A8 in Appendix). (In the Netherlands, €20 000 per additional year lived in full quality health is usually considered cost-effective; Brouwer et al. (Reference Brouwer, van Baal, van Exel and Versteegh2019).)

Discussion

This pilot RCT aimed to test trial procedures, treatment facilitators and barriers, and likely effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PM+ among Syrian refugees in the Netherlands. Our findings suggest that the adapted PM+ protocol is acceptable for use among Syrian refugees. Participants, helpers and key informants were generally positive about the intervention, including the PM+ strategies, accommodation (e.g. reimbursement of travel expenses) and delivery by Syrian helpers. Training and structural supervision of peer-refugees was perceived feasible and acceptable. These findings are further supported by helpers' adherence to the protocol and low participant drop-out from the intervention. Two adverse events unlikely attributable to the trial or intervention were reported by participants, suggesting that PM+ is a safe intervention. However, some participants may have experienced shame from trial participation.

Although the study was not powered to detect significant differences, depression and anxiety symptoms improved in the PM+/CAU group relative to the CAU group, with moderate effect sizes. The study also indicated moderate to large improvements in overall psychosocial functioning, PTSD symptoms and self-identified problems. No significant difference in health service utilisation or costs was observed between groups, but overall costs were significantly higher in PM+/CAU due to PM+ implementation costs. Mean intervention costs ultimately are likely to be lower if trainers and helpers can be retained and continue to deliver PM+ to more refugees over a longer time period. Nonetheless, our exploratory economic analysis suggests PM+ has the potential to be cost-effective from a health system perspective.

The moderate improvements across a broad range of symptoms are in line with previous PM+ trials (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017), and support the intervention's transdiagnostic feature (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). One key finding is that, although PM+ is not a trauma-focused intervention, it improved PTSD symptomatology in this war-affected sample. This adds to existing literature indicating PTSD symptoms can be successfully treated with brief, non-trauma-focused interventions (Nidich et al., Reference Nidich, Mills, Rainforth, Heppner, Schneider, Rosenthal, Salerno, Gaylord-King and Rutledge2018; Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Ballette, Bird, Carswell, Churchill, Cuijpers, Hall, Hansen, Kösters, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Sijbrandij, Tedeschi, Valimaki and Barbui2019).

This is the first study exploring how PM+ can be delivered by peer-refugees in a high-income country. Although refugees are typically exposed to ongoing post-migration stressors, our study showed that effects were retained up to 3 months. A key strength in this study is the mixed-methods design that enabled us to examine both quantitative outcomes in a rigorous RCT, as well as perceptions of various stakeholders about the acceptability and feasibility of PM+. Another strength is the use of the secondary outcome measure PSYCHLOPS, which examines participant-generated problems, instead of ‘Western’ mental health constructs. Furthermore, we added the WHODAS measure of overall psychosocial functioning to look beyond mental health and psychosocial problems, something often not included in the evaluation of psychosocial interventions for refugees (Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Ballette, Bird, Carswell, Churchill, Cuijpers, Hall, Hansen, Kösters, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Sijbrandij, Tedeschi, Valimaki and Barbui2019).

Our study also has a number of limitations. First, we failed to interview study drop-outs in our qualitative evaluation, limiting our insights on barriers to trial participation. Second, although treatment effects and cost-effectiveness results are promising, they should be interpreted with caution as no power calculations were carried out. Furthermore, participants were recruited from a foundation established for Syrian families with resident status living in an urban area, and results might be different for those still awaiting completion of their asylum procedure.

A major practical implication of the present pilot RCT is that the study and PM+ procedures can be successfully carried out among Syrian refugees. The observed low drop-out is promising for a definite RCT. Use of Audio-Computer-Assisted Self-Interview software (e.g. Morina et al., Reference Morina, Ewers, Passardi, Schnyder, Knaevelsrud, Müller, Bryant, Nickerson and Schick2017) that does not require administration by an assessor may improve blinding.

Longer term follow-up is needed to better assess whether there is an impact on health service utilization and social functioning outcomes such as participation in work and study. With a larger sample size, it will also be possible to estimate changes in quality of life outcomes, using a generic outcome measure such as the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY), a metric that has resonance with policy makers. Replication in a fully-powered RCT is needed (see De Graaff et al., Reference de Graaff, Cuijpers, Acarturk, Bryant, Burchert, Fuhr, Huizink, Jong, Kieft, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Morina, Park, Uppendahl, Ventevogel, Whitney, Wiedemann, Woodward and Sijbrandij2020). Other trials on PM+ with different modes of delivery (e.g. group) will be conducted in the larger STRENGTHS project (Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Acarturk, Bird, Bryant, Burchert, Carswell, de Jong, Dinesen, Dawson, El Chammay, van Ittersum, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Miller, Morina, Park, Roberts, van Son, Sondorp, Pfaltz, Ruttenberg, Schick, Schnyder, van Ommeren, Ventevogel, Weissbecker, Weitz, Wiedemann, Whitney and Cuijpers2017). This will strengthen the external validity of trial findings and provide a potential model for scaling up in more and less well-resourced contexts.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the trial procedures and PM+ delivered by peer-refugee, non-specialist helpers are acceptable, feasible and safe. PM+ is likely effective in improving mental health outcomes and psychosocial functioning in Syrian refugees, and potentially cost-effective. A fully-powered, definitve RCT with longer follow-up is needed.

Data

The Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU) will keep a central data repository of all data collected in the STRENGTHS project. The data will be available upon reasonable request to the STRENGTHS consortium. Data access might not be granted to third parties when this would interfere with relevant data protection and legislation in the countries participating in this project and any applicable EU legislation regarding data protection. Interested researchers can contact Dr Marit Sijbrandij at [email protected] to initiate the process.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the helpers and other staff members of SNTR for their collaboration on implementing PM+; and research team members Jana Uppendahl, Ine Smeets, Shuker Barbour, Yenovk Zakarian and Dima Aldabous for conducting assessments and interviews.

Financial support

This study was supported by Stichting Nieuw Thuis Rotterdam and the STRENGTHS project. The STRENGTHS project is funded under Horizon 2020 – the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2014–2020). The content of this article reflects only the authors' views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 200.

Trial registration

Appendices

Appendix 1: Checklists

Checklist A1. CONSORT 2010 Checklist of information to include when reporting a pilot or feasibility trial

Checklist A2. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) Checklist

Checklist A3. Individual PM+ helper's component checklist

Appendix 2: Tables Table A1. Unit cost (2018 euros)

Table A2. Qualitative analysis themes and related quotes

Theme 3: Experiences of training and supervision

The PM+ supervisor described the weekly supervisions as ‘hard work’ because the helpers had no background in psychology (KI5). Both supervisor and helpers experienced that further practice of PM+ skills during supervision increased helpers' ability to model the strategies to participants and adhere to the protocol (Q3.1–2). Helpers described supervision as a way ‘to learn from each other’ (H2) and ‘improve their approach’ (H4) (Q3.3). Communication between supervisors and helpers was in Dutch, but some of the role-play was in Arabic (to practice how PM+ will work with participants).

Individual case monitoring was mainly used to support tailoring PM+ to the individual (Q3.4), and to detect and potentially refer those with possibly more severe mental health problems (e.g. substance abuse) to professional care (Q3.5). Several KIs, however, expressed concerns about the current waiting lists for such professional help.

Recognition of participants' stories was helpful though potentially burdensome for helpers (Q3.6). They explained that hearing about other people's problems could be challenging, but that supervision and talking to colleagues helped them (Q3.7). The supervisor emphasised the importance of self-care during supervision, given the similarity of experiences (emotional burden), and because helpers carried out the sessions alongside their regular work for SNTR (time burden). Both helpers and the supervisor spoke about the importance of knowing ‘your limits’ as helper. One helper was asked to briefly put PM+ as extra activity in her regular work ‘on hold’ due to signs of burn-out.

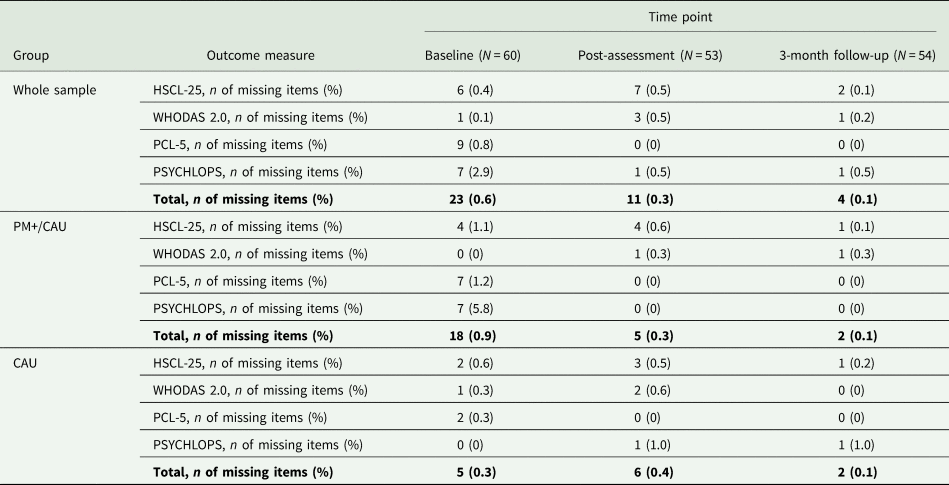

Table A3. Missing data pattern

The percentage of missed assessments (unit non-response; Brick and Kalton, Reference Brick and Kalton1996) in the study was 7.2%. Eighty-seven per cent (86.7%) of participants completed all three assessments. There were more assessment skips in the CAU group (13% at both post and 3-month follow-up) than in the PM+/CAU group (10% at post and 6.7% at 3-month follow-up). Reported reasons for non-attendance across assessments were ‘prefer to withdraw’ (n = 3), ‘lack of time’ (n = 3), ‘abroad/unavailable’ (n = 1), and ‘no approval from spouse’ (n = 1).

The percentage of missing items (item non-response; Brick and Kalton, Reference Brick and Kalton1996) across the primary outcome variable HSCL-25 and secondary outcome variables WHODAS 2.0, PCL-5 and PSYCHLOPS varied between 0.1–2.9% (baseline), 0–0.5% (post-assessment) and 0–0.5% (3-month follow-up). We assumed data to be missing at random (Little and Rubin, Reference Little and Rubin2002). Table A3 presents missing values per outcome variable.

We used pro-rated, single imputations for outcome measures with missing items. We did not impute unit non-response, as linear mixed-models in R handle missing outcome data (Raudenbush, Reference Raudenbush2001).

Table A4. Summary statistics and results from mixed-model analysis of primary and secondary outcomes without PM+ non-completers

Table A5. Reliable change index at post-assessment and 3-month follow-up for the HSCL-25 (completers only)

Fig. A1 Cost-effectiveness plane: PM+/CAU v. CAU per recovery achieved (health system perspective).

Fig. A2 Cost-effectiveness plane: PM+/CAU v. CAU per recovery achieved (health system and productivity perspective).

Fig. A3 Cost-effectiveness plane: PM+/CAU v. CAU per improvement achieved (health system perspective).

Fig. A4 Cost-effectiveness plane: PM+/CAU v. CAU per recovery achieved (health system and productivity loss perspective).

Fig. A5 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: willingness to pay per improvement achieved from PM+/CAU intervention (health system perspective).

Fig. A6 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: willingness to pay per improvement achieved from PM+/CAU intervention (health system perspective).

Fig. A7 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: willingness to pay per recovery achieved from PM+/CAU intervention (health system perspective).

Fig. A8 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: willingness to pay per recovery achieved from PM+/CAU intervention (health system and productivity perspective).