Introduction: Lars von Trier and auteurism

Early on, the filmmaker born Lars Trier understood and presented himself as the primary creator of his films: ‘One could say that Lars Trier's project was not primarily to make films but to construct Lars von Trier, the auteur filmmaker.’Footnote 1 In his first film trilogy, Europa, Trier appears in every film. In Zentropa (aka Europa) and The Element of Crime, he provided brief cameos, a gesture common among auteur filmmakers since Alfred Hitchcock. In Epidemic he took on the film's lead role and played himself writing a script for a film, one in which he likewise portrays the protagonist. But his performance also attracted attention beyond his films. After the 2011 press conference in Cannes for Melancholia, he was declared persona non grata due to scandalous comments about Hitler; he then took a vow of silence, and had himself photographed with his mouth taped shut as part of the publicity for his next film, Nymphomaniac.Footnote 2 Shortly before the press conference for Antichrist in Cannes, he praised himself as the ‘best film director in the world’.Footnote 3 From the beginning of his career he was anything but modest, proclaiming that he had decided in advance to make Zentropa a great masterpiece.Footnote 4 For Trier, the fact that such projects require the participation of actors was mainly an obstacle: ‘They are the only thing that stands between you and a good film.’Footnote 5 He has emphasized several times how important it is to him that actors subordinate themselves to their director: ‘For me, it's an indication of professionalism that actors follow the director's instructions. It's his vision … Danish actors would demand to “understand” their roles. But what is there to understand if the director knows precisely what he must have?’Footnote 6 After he was awarded the Sonning Prize, Trier stated in an interview, ‘I believe that all good art is created under dictatorial conditions.’Footnote 7

The conception of films as the products of a single director do not stem from self-evident arguments. On the one hand, despite these influential public assertions of filmmakers such as Lars von Trier, industrial film production involves many people. On the other, movements advocating for the director's artistic control over film production have appeared and persisted without rest since the 1940s: Italian Neorealism, French Nouvelle Vague, New German Cinema, New Hollywood as well as the Danish Dogme 95, the latter influenced decisively by Trier. Director François Truffaut, himself a pioneering film critic, pushed for auteurism, that directors should exert more control over their films.Footnote 8 Ambassadors for these movements claimed authorship solely for the figure of the director. In doing so, such movements proposed that films represent the works of individual authors, rather than collaborative and so largely anonymous products of an entertainment industry. Auteur cinema also promised to offer a social revaluation, elevating film from its ‘shady’ existence to an independent artform.Footnote 9

While the identifier ‘auteur’ seems a politically, socially, and critically convenient term, real production circumstances complicate its accuracy for any form of film criticism. Because authorship is a construct, one involving filmmakers and audiences, as well as spanning from production through distribution to reception, critical conceptions of the singular auteur never needed to correspond with the realities of films’ production cycles in the first place. For while we can certainly understand the concept of authorship as a makeshift shorthand for combining interactions among numerous persons into one, we can also understand it as one way of combining different texts into an identifiable group. Michel Foucault's construction of the author can serve as an analytical approach to films by the same director, to bundle them together and place them in a specific relationship with one another.Footnote 10 Yet while this level of abstraction can simplify corpora, reducing them to manageable units, it still generates a linguistic reality that, strictly speaking, does not correspond to the realities of film productions, and may even contradict them. Existing discourses construct this apparent power imbalance by reducing collaborations to one person. The Canadian novelist Michael Ondaatje draws attention to this discrepancy between real practice on the set and the idea of the director as a form of author in the reception of the Sun King narrative:

It is hard for any person who has been on the set of a movie to believe that only one man or woman makes a film. At times a film set resembles a beehive, or daily life in Louis XIV's court – every kind of society is witnessed in action, and it seems every trade is busy at work. But as far as the public is concerned, there is always just one Sun-King who is sweepingly credited with responsibility for story, style, design, dramatic tension, taste, and even weather in connection with the finished project. When, of course, there are many hard-won professions at work.Footnote 11

In this article I build on Ian Macdonald's concept of the ‘Screen Idea Work Group’ to describe production-situated perspectives, placing these in dialogue with Claudia Gorbman's idea of the ‘auteur mélomane’, as a means to clarify reception-situated analyses in turn.Footnote 12 I therefore propose the concept of a ‘Musical Idea Work Group’ (MIWG) as a fusion of these approaches, a counterweight to the ideology surrounding ‘auteur’. I take Lars von Trier as a case study, a film personality unequivocally received as an auteur mélomane.Footnote 13 Given the repeat presence of job titles in film credits such as music supervisor, sound designer, and music researcher, a question occurred to me: Why do we consider musical design the director's achievement? Whether or not the realities of his productions support this supposition is one stream of inquiry I explore here with improved accuracy by acknowledging Trier's collaborators and accounting for their own perspectives on their creative inputs.

In creativity studies there is the idea of ‘the four P's’: the person, the process, the product, and the press that surrounds them.Footnote 14 Traditionally, film music research and the press concern themselves with examining either two groups of people, namely directors and composers, or the final products, the films and musical compositions. In this article, I foreground neither the single auteur figure nor the final product, but rather the highly collaborative processes in which people develop new film-musical ideas. The basis for my analysis of these production processes draws on qualitative and semi-structured insider interviews that I undertook in Copenhagen across 2020 and 2021.Footnote 15 I spoke with the composers, sound designers, musicians, music supervisors, and editors for Trier's films who have first-hand information and specialist knowledge about the inner workings of film productions. With these in hand, the present article offers new insights into the work of contemporary filmmakers who use pre-existing music in general, and the working processes behind Trier's film projects in particular.

The auteur mélomane

Claudia Gorbman labels those directors seemingly obsessed with musical interpretations of their films as ‘auteurs mélomanes’, extending the concept of the auteur to include music:

More and more, music-loving directors treat music not as something to farm out to the composer or even to the music supervisor, but rather as a key thematic element and a marker of authorial style.Footnote 16

This attribution of diverse implementations of pre-existing music simplifies and obscures the number of people involved in film production processes.Footnote 17 Nevertheless, the prevailing reception of auteurs demands attention in order to understand the popular impression that the director is the person generally responsible for musical decisions in films that feature music prominently. The popular identification of the auteur as the primary (or even sole) ‘author’ further suggests the degree to which many viewers associate the category of film authorship more generally with the director.

Gorbman's framework for the auteur mélomane unveils two general tendencies in their reception: recent constructions of authorship clearly include musical dimensions, and academic reception contributes significantly to this construction, if perhaps unknowingly. Since at least the films of Stanley Kubrick, critics have held that the use of pre-existing music constitutes a signature of the auteur.Footnote 18 As directors usually do not have the ability to write music for their films,Footnote 19 pre-existing music offers them greater control over the cinematic soundtrack.Footnote 20 The director can work as a composer in the literal sense (componens, ‘the person who puts together’), without writing a single note.Footnote 21 As Jonathan Godsall observed, ‘Compilation practice, once a signifier of a film made cheaply, quickly, and perhaps by committee, could now signal an auteur in full control of their vision.’Footnote 22 Digitization proved crucial for this development as both a practice and an aesthetic:

The digital revolution has made music ever more accessible and malleable as an increasingly personal means of expression. It has abetted the tendency among auteur mélomanes to take more active control of music, an element of filmmaking that previously eluded them as they had to rely on specialists to fabricate it.Footnote 23

Musical technologies facilitated the widespread use of pre-existing music.Footnote 24 Even though the use of pre-existing music is a time-honoured practice in film, digitization changed the ways filmmakers could work with the soundtrack: they can search for music on the internet, download songs, or copy and paste music instantly into their films using digital editing software. Trying out Beethoven's Fifth or Queen's ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ in a scene is little more than a few clicks away. More recent compiled scores also reflect the rise of digital music and streaming services. Once stylistically consistent, compilation scores today can be as eclectic as any streaming playlist, and so for new digital cinema became a ‘specially curated pastiche of pre-existing music’.Footnote 25

Trier's image as an auteur filmmaker and mélomane builds on his use of pre-existing music. Of his twelve feature films released in the period from 1984 to 2018, only the two early films The Element of Crime (1984) and Europa (1991) feature original film music in a classical sense, that is, (orchestral) music composed especially for the film (by Bo Holten for the former, and Joachim Holbek for the latter). Furthermore, his mélomanie extends beyond his work in cinema, including music videos, a planned staging of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen at Bayreuth in 2006,Footnote 26 and separate collaborations with famous musicians such as Björk,Footnote 27 Lars Ulrich, and Nina Hagen, among others. The compilation scores in his films also increased in their eclectic range of pre-existing selections over time, though Trier shows a consistent taste for David Bowie and Richard Wagner. For a better understanding of Trier's authorial hand, we can turn to a closer examination of pre-existing music as a category.

Pre-existing music

The question of whether a film's score is pre-existing music depends upon the music's referentiality, or its capacity for allusion. To answer this question more accurately, distinguishing between reception and production proves helpful once more. When received and acknowledged as pre-existing music, these scores refer us as listeners to another instance of that music's existence outside the film. Any music can be used and perceived as pre-existing music so long as its point of reference is a specific musical text that exists beyond the film. Extra-filmic texts include musical scores, extant musical records that predate the film, and other filmic adaptations. Even music originally composed for an older film can function as pre-existing music when filmmakers use it in another, newer film. Filmic uses of pre-existing music therefore present a form of intertextuality, ‘a relationship of copresence between two texts’,Footnote 28 through the ‘actual presence of one text within another’.Footnote 29 Perceiving music as pre-existing means the audience receives the music in the film in relation to its extra-filmic text.

Filmmakers appropriate recognizable pre-existing music for film productions from a specific extra-filmic text. That process of appropriation necessarily involves some degree of interpretation, even creation. Those choices generate meaning through their very tensions across two related dimensions. On the one hand, there are tensions between pre-existing music and how it is edited for the film. These configurations present intramedial conflicts of texts. On the other hand, film adaptations of pre-existing music offer intermedial conflicts between the music's existing contexts and its new filmic contexts. Intramedial conflict acts intertextually, between filmic and extra-filmic versions of some music, while intermedial conflict takes place intratextually, or within the film, between musical and extra-musical elements therein.

Pre-existing music comprises simultaneously a cinematic recontextualization of music and its musical editing for the film. If we understand that music only exists as pre-existing music through its use and its reception, then appropriation makes music function as pre-existing. This appropriation offers an interpretative and creative translation of another recognizable musical text: in the literal sense, a recontextualization, and in the metaphorical sense, a transformation into another form.

The Musical Idea Work Group (in theory)

How do filmmakers work with pre-existing music? For a production-situated perspective, I build on Ian Macdonald's concept of the Screen Idea Work Group, a

flexibly constructed group organized around the development and production of a screen idea; a hypothetical grouping of those professional workers involved in conceptualizing and developing fictional narrative work for any particular moving image screen idea.Footnote 30

To better understand the dynamic processes of film production, Macdonald argues, it is helpful to imagine a flexible crew working across both formal and informal groupings to shape a ‘screen idea’. I find this model more effective than linear models imagining a succession of individuals along an industrial production line for the film's script.Footnote 31 The Screen Idea Work Group more accurately describes increasingly common collaborative processes, treated by linear models as complications. Macdonald furthermore defines the screen idea as ‘the core idea of anything intended to become a screenwork’.Footnote 32 That being said, Macdonald did not intend for this concept to deconstruct authorship:

the Screen Idea Work Group is not intended to replace the sense of individual authorship, despite the implication that collectively the SIWG is the true site of the emerging screen idea. Attribution of, or credit for, creative ideas is not the purpose of this way of studying screen idea development. It is instead intended as a way of understanding what actually happens when a moving image narrative is conceived, developed and produced.Footnote 33

During my conversations with filmmakers, I recognized that script development and film-musical production process today operate similarly as flexible work groups, both formally and informally. I therefore propose that these film-musical teams constitute a ‘Musical Idea Work Group’, or MIWG. While Gorbman's auteur mélomane reflects public reception, the MIWG addresses realities of film production in situ. Within this notion of a MIWG, I include every person who comes together in developing a film-musical idea, every key worker involved directly in the idea's development, whether officially affiliated or not. As a descriptive tool, the MIWG therefore accounts for the extreme flexibility of contemporary film production, instead of a linear collection of specified roles or practices.

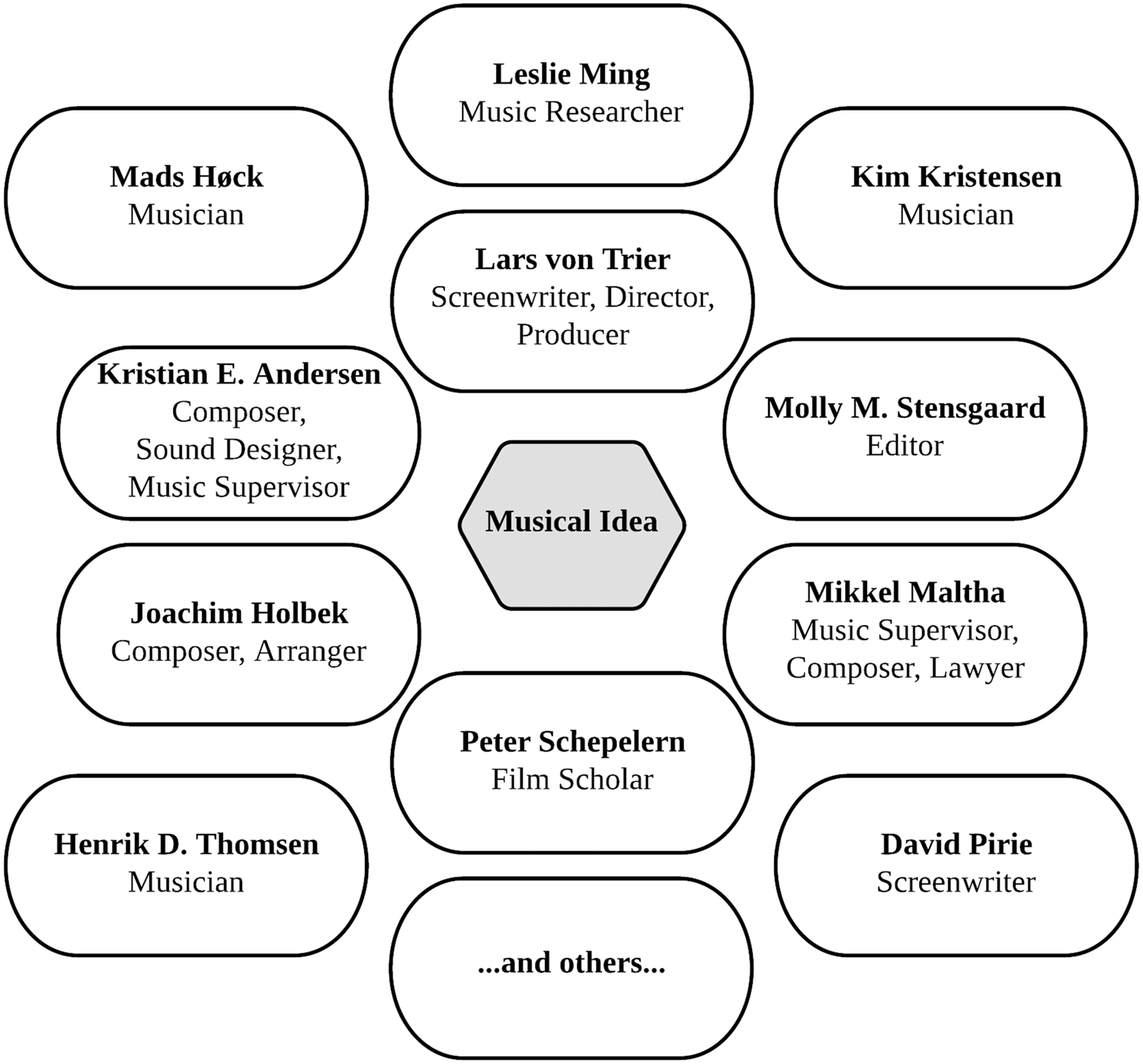

Trier's cross-film MIWG consists of at least eleven members. I reconstructed this network through archival research and insider interviews in Copenhagen. Each member directly shaped film-musical ideas in Trier's films. As the first case study in identifying who constitutes a MIWG, my rhizomatic structure of the relationships among Trier's MIWG attempts a more inclusive collection of participants (Figure 1). This is not an exhaustive list; I also believe additional members remain invisible due to their unofficial affiliations.

Figure 1 The Musical Idea Work Group in the films of Lars von Trier.

We can also define subgroups of the MIWG. Some job titles suggest clear and immediate affiliation with the MIWG, such as composer, arranger, sound designer, music supervisor, music researcher, and musician, while others, at least on the face of it, do not, such as film scholar, editor, or screenwriter. We can also divide them up among official and unofficial affiliations.Footnote 34 For example, Peter Schepelern's and David Pirie's contributions were not listed in the credits. For my visual schema, I chose to illustrate relationships based on their relative influence on film-musical ideas, and so differentiated narrower and wider circles of collaboration.

I define the inner circle as those persons involved in ongoing collaborations. Joachim Holbek and Kristian E. Andersen were more involved in the auditory design of Trier's films than anyone else. Except for The Element of Crime and Epidemic, one or both of them were involved in every film project. Holbek, as Trier's brother-in-law, debuted as a film composer in Trier's 1988 TV production Medea. Andersen first joined the MIWG in 1996 with Breaking the Waves as supervising sound editor. We can add to this inner circle Molly M. Stensgaard, Mikkel Maltha, and Peter Schepelern. Molly M. Stensgaard's collaboration with Trier began with the series Riget (1994). She has since edited almost all of Trier's productions. Mikkel Maltha began largely as a legal advisor for Trier's film productions, starting with Dancer in the Dark, though his role in determining musical ideas expanded gradually. Film professor Peter Schepelern taught Trier in university and sees himself as his mentor, accompanying Trier as a cultural-historical consultant.

The outer circle includes mostly one-off collaborations. These include Mads Høck (the organist for Nymphomaniac), Kim Kristensen (who played melodica for Idioterne), Leslie Ming (music researcher for The House That Jack Built), and David Pirie (one of the screenwriters for Breaking the Waves). Only the cellist Henrik Dam Thomsen was involved in several projects. He recorded César Franck's Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano for Nymphomaniac with Ulrich Stærk, overdubbed the cello cantilena of the Tristan Prelude in Melancholia for a ‘more passionate sound’,Footnote 35 and co-created the cello sound effects in The House That Jack Built.

In the course of my fieldwork with members of the MIWG, I found sharp correctives to my own presumptions about their work, and at every level of involvement. While my production-situated perspective aimed to gather new insights into production processes, I quickly realized multiple pitfalls while trying to design questions that could illuminate realities and not merely confirm ideas or preconceptions I brought with me. For one, I presumed at the outset that the filmmakers would reject the idea of Trier as an auteur mélomane. I expected a contradiction between reception and production, rooted in my firm belief that musical design depends on collectives of people. I expected conflict over how the ideology of a singular auteur mélomane plasters over or marginalizes the collective's achievements. I even found myself irritated when more than one MIWG member provided statements that served the received narrative of Trier as the driving force of production:

It was all Lars’ idea. He knew exactly what he wanted and I just followed his instructions.Footnote 36

I think Lars works with music in a very unexpected way. And that's pretty much his brilliance. It's all in his mind. He's very fond of music. He usually has very strong ideas about music upfront. If you read the scripts, you see that he often mentions music at that stage!Footnote 37

Lars is very precise with what he wants. He knows from the script stage what kind of music should appear in the film.Footnote 38

It's mostly his [Trier's] idea. He always has a very clear idea about the music. At the same time, he's always open to try different things and to work with what is on the table.Footnote 39

Contrary to my initial assumptions, some people directly involved in the development of film-musical ideas attribute primary agency to Trier. Conversely, there are reasons to be sceptical of such assertions. I made sure to inform every group member that their statements could appear in publication. This ethical disclaimer could well have shaped their stance towards answering my questions. What at first glance might appear unfiltered insider information can turn out as a choreographed cultural performance. Moreover, the narrative of the director as the Sun King informs not only reception but also production culture. In Macdonald's fieldwork while developing his Screen Idea Work Group, a majority of the writers he encountered held orthodox received views, ‘that do little to illuminate the process of screen idea development, except to show that their holders have absorbed professional screenwriting culture to a point where they rarely question their practice and accept it as the norm’.Footnote 40

The Musical Idea Work Group (in practice)

Defining the concrete tasks of MIWG members can prove tricky, precisely because job titles such as music researcher or music supervisor are not clearly defined within the industry. Tasks range from budgeting, scheduling, clarifying music rights, and obtaining licenses, to researching and selecting music.Footnote 41 Music supervisors are often lawyers who are also music enthusiasts, or musicians with interest in media rights law. Mikkel Maltha is listed in the credits as ‘Lawyer’ (Dancer in the Dark), ‘Production Lawyer’ (Dogville and Manderlay), ‘Legal Advisor’ (Antichrist), and ‘Music Supervisor’ (Nymphomaniac, Melancholia, and The House That Jack Built). Given this range of activities, I found myself dependent on insider interviews as an essential tool for understanding their collaborative pathways. ‘Ninety per cent of the time’, said Maltha of his work for Trier, ‘I am responsible to clear the rights.’Footnote 42 When asked, he explained how he spends his remaining 10 per cent:

Sometimes I play him [Trier] some music. And I remember playing the Glenn Gould clip which appears in The House That Jack Built a long time before he wrote the script. This is one of the few examples I contributed to the films from a creative point of view.Footnote 43

These episodes in production show how informal pathways appear among an MIWG. Many interviewees described similar informal procedures:

Other pieces of music with very different character were suggested [for Idioterne]. I recorded different possible pieces in my studio and Lars von Trier listened and luckily he chose ‘The Swan’.Footnote 44

It's very much trial and error. During the production of Dogville, for example, we tried a lot of different musical pieces and at some point Lars would just say ‘Yes, I like this!’ Yet, he very early decided to use baroque music. So it's kind of trial and error, but definitely trial and error with a plan.Footnote 45

For Antichrist we wanted to create a feeling of unease via a crossover between sound design and music. Lars had the idea to use only organic material, no classical instruments. For several months we met every day for half an hour and made the ‘sound of the day’, as we called it. We tried different things, like cracking branches, hitting stones against each other, blowing on leaves. I then sampled and manipulated these sounds in the studio. There were certainly days when we doubted the idea. But in the end I am satisfied with the result.Footnote 46

There is a great, great element of playfulness and simple trial and error in working with Lars. He would always avoid the solution right in front of him. If you don't try things out, you never get that far away from the most expected solution. And then you never find the really interesting solutions. So nothing is ever too stupid to be tried out. In fact, we found that sometimes the really good solution is right next to the really stupid solution. This kind of experimentation is even expected in the working process with Lars. Everyone would be disappointed if stupid solutions were not tried. We know that this is a huge privilege. It comes with a master like him. We take a lot of time in the editing process and the goal is not to be efficient or to reach the right solution very quickly.Footnote 47

Trier often appears to be the final decision-maker. However, the options on the table are from the MIWG. While Trier is commonly perceived as the originator of musical ideas, these accounts relate how his real working processes include cooperative trial and error. Per Stensgaard, trial and error appear to be an explicit goal for this specific team's shared methodology. In explaining this way of working, she accordingly emphasizes a collaborative and dynamic character to their collective work on the soundtrack:

We already work with music during the editing of the first or second cut. Ideally, I already start my collaboration with Kristian [Andersen] at this point. So this process takes place quite early and is very dynamic. He constantly feeds Lars and me with sounds and music. Of course, this is not finished material. It's very much trial and error again: Kristian would try things out and give them to us, we would say ‘wow, that's really interesting, but maybe it could be more like this or that’. That's how we pass sequences back and forth. Mikkel [Maltha] would also supply some music that he knew he could buy the rights to use in the film. And of course Lars and I would also sometimes search the internet for music. So it's really a dynamic process and a constant exchange of ideas. Compared to other sound designers and editors, I would say it's very unusual that we work so parallel in the process. And that's a great quality, but of course it's also much more expensive. And you have to trust your colleagues a lot to share your unfinished material. For example, when I was working on Melancholia, I thought I had made a brilliant music edit. Then I gave it to Kristian and of course, as a composer, he wasn't, let's say, totally convinced by it. So he rearranged everything. But the important thing is that I could indicate what I wanted with the music and Kristian could then work with it. I am convinced that this kind of productive collaboration increases the quality of the film.Footnote 48

The music and sound design play integral parts in the early phases of post-production. Moreover, according to Stensgaard, the group constantly exchanged ideas among her, Andersen, Maltha, and Trier. Based on these interviews, I came to differentiate two dimensions of appropriation: intermedial tension provided by the cinematic recontextualization of pre-existing music, and intramedial tension produced by the editing of that pre-existing music for the film. Here we see how the film's editor not only influences recontextualization, but also can impact more directly the musical editing.

Stensgaard also cites Dogville to explain how film-musical ideas can materialize out of working group processes:

When it comes to the music, I think one of the most interesting processes was for Dogville. In the beginning Lars had the idea that it should be authentic music from the time and place of the film, so some kind of blues music. So we tried that for the pilot and we thought ‘ugh, that's not good’. It was kind of too direct or too connected to the story. Then for some reason Lars and I saw Barry Lyndon and we loved the baroque music in the film. So we decided to try that music once, but only once. We were quite afraid of liking this music in Dogville, because obviously it wouldn't be possible to actually use it. In a way, this baroque music is completely off the track. There's no connection with the setting or the reality of the film. But it immediately felt really, really good. So we decided to use baroque music. Since we couldn't use Barry Lyndon's music, we checked if there was a person in Copenhagen who knew everything about baroque music. So we found this ‘Mister Baroque’, an old gentleman, and he came out with some very interesting music. I think it's really surprising how well this music works in the film without having any relation to the time and place of the story!Footnote 49

People can be brought into the MIWG for their attributed expertise, even without any official affiliation with the project. Such collaborations often project a significant influence on the development of the eventual film-musical idea. At the same time, because unofficial consulting often takes place privately, those persons usually do not appear in the credits. This has also been the case for Peter Schepelern as a film scholar:

Lars always asked me about literature, classical music, and film history. When he worked on Nymphomaniac, he was very interested in Marcel Proust. I remember that he asked me about the ‘Vinteuil Sonata’ in À la recherche and whether it really existed. I told him that there are a few musical pieces that could be meant by Proust, but that I believe the most suitable would be the first movement of César Franck's Violin Sonata. After he had listened to this piece, he said ‘This piece is wonderful! It fits perfectly!’ … When he was working on Antichrist, Lars was looking for music with a very vocal sound. I pointed him to Saint-Saëns’ ‘Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix’ and the wordless female voice in Villa-Lobos’ ‘Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5’.Footnote 50

While many MIWG contributors attribute the greatest portion of agency to Trier, their descriptions of the concrete work processes clarify how Trier does not always enter with a clear film-musical plan to implement in the ultimate product. Even if Trier seems to make the final decisions in many cases, his initial musical ideas are often rather vague, taking shape over the course of collaboration with various people.

We have already seen how film-musical ideas can consist of a music-historical period (Dogville), a literary character (Nymphomaniac), or a specific musical sound (Antichrist). Related working processes extend beyond formalized music into broader issues of filmic sound design. Henrik D. Thomsen, credited for ‘Cello FX’, described to me how sounds as effects and soundworlds played equally important roles in the film-musical idea for The House That Jack Built:

With The House That Jack Built the three of us [Trier, Andersen, Thomsen] met with the purpose of creating ‘the sound of hell’. Lars wanted to test the highest and the deepest possible notes on a cello. We recorded a long line of scratchy overtones and harmonics as well as extremely deep sounds on a tuned down c string. The result came out as a mix of the sounds.Footnote 51

In the final film, this ‘sound of hell’ consists of these cello sounds in combination with drum recordings by Lars Ulrich and Alex Riel during an impromptu ‘foray’.Footnote 52 Concrete sonic realizations like these lead to conceptual distinctions between pre-existing music and pre-existing recordings.

Pre-existing music and pre-existing recordings

Jonathan Godsall distinguishes between allosonic and autosonic quotations of pre-existing music.Footnote 53 This conceptual distinction goes back to Nelson Goodman's conceptual pairing of autographic and allographic artworks.Footnote 54 As Serge Lacasse applied this distinction to recorded popular music, so Godsall extended Lacasse's argument to pre-existing music in film:

Allosonic quotation is the quotation of abstract musical structure, which Lacasse illustrates with the example of a jazz musician quoting ‘a snatch from another tune’ during an improvised solo. Autosonic quotation, on the other hand, is the quotation of recorded sound, the appropriation of something ‘of a physical nature’, as in the practice of sampling a drum beat from a James Brown record into a new hip-hop track. Lacasse's definitions map comfortably onto the use of pre-existing music.Footnote 55

For film, music is either re-recorded (allosonic) or a pre-existing recording is directly integrated (autosonic). Godsall's distinction might give the impression that autosonic quotations appear unedited in films. However, this is not strictly the case. Even pre-existing recordings are edited for film, such as through musical cuts and time-stretching. Often the music on the film soundtrack already sounds different from in non-film contexts due to technological factors. In addition to the film-specific experience created by the sound mix, different video formats can significantly change the pitch and speed of pre-existing music.Footnote 56 Moreover, a pre-existing recording can be edited to reference another musical recording, as we will see later. The possibilities afforded by digital sound editing blur the line between allosonic and autosonic quotations, as new sonic realizations emerge increasingly from work with pre-existing recordings. Even the adaptation of pre-existing recordings involves practices of both cinematic recontextualization and editing for film.

The distinction between pre-existing music and pre-existing recording plays an important role within the MIWG. ‘Lars chooses the music’, said Mikkel Maltha, ‘but when it comes to the actual recording, I have plenty of rope; usually I'm the one who selects the recording’.Footnote 57 Leslie Ming, who worked as a music researcher for The House That Jack Built, similarly emphasized that her main activity was ‘clearing the music rights and finalizing the paperwork’.Footnote 58 But she also told me that she found the specific recording of ‘Hit the Road Jack’ for the credits:

Lars did not wish to use Ray Charles’ version of ‘Hit the Road Jack’. Why I do not know. So I got the task to find the best cover versions of the song and present them to him. Let me tell you – there are a lot of cover versions of ‘Hit the Road Jack’! Ultimately I found this obscure, quirky version on YouTube by Buster Poindexter (David Johansen from New York Dolls), which had female choir voices on it. I thought there was no way in hell that Lars would pick that one out of all of them, but surely he did.Footnote 59

Ming's description illustrates our prior differentiation between the agency of the MIWG members (Ming searching for song covers and suggesting, among others, this one) and the auteur mélomane as the final decision-maker (Trier choosing this version). The musical idea here consisted of a pre-existing musical work, yet strove to avoid the work's most popular recorded performance. However, the idea can also target a specific pre-existing recording:

Originally, Lars wanted the film [The House That Jack Built] to end with a Louis Armstrong song. But it was a very particular version he wanted to use, which was very old, and we could not find the master owner. It had switched hands over the years and the labels did not know who had it now. You have to be very careful with American masters, so we did not want to take the risk of putting it on the end credits without having paid the master owner.Footnote 60

In order to use a musical recording, filmmakers must obtain special licences (usually the ‘synchronization licence’ and ‘master licence’) from the master owner (‘clearing’ rights).Footnote 61 Ming's statement reminds us how film productions today are attached to financial and structural conditions that can make the realization of certain film-musical ideas impossible.

The importance of a pre-existing recording to the film-musical idea does not necessarily mean that MIWG's goal will be to license that recording for the film. When recording Bach's ‘Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ’ for Nymphomaniac, the idea was, instead, to get as close as possible to the interpretation of that same piece in Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris. As Trier's organist Mads Høck recalls:

Lars wanted to quote Tarkovsky's Solaris. And I thought when he contacted me he wanted just to hear this very beautiful piece by Bach played as we play Bach now and not as they did back in the seventies with this very hard Sesquialtera stop. I wanted to play the solo with a reed, an oboe, or something like that, but Lars insisted that it should be exactly the same sound as in Solaris. I even added a lot of trills and ornamentations because that's the way baroque music is played now but they didn't do that in the seventies when Solaris was recorded. And Lars didn't want all these trills. So we made this very pure version. It was very clear that this was what he wanted, this very clear reference to Tarkovsky.Footnote 62

The intertextuality between Solaris and Nymphomaniac thus arises not only from the selection of pre-existing music or its similar cinematic context, but also from the concrete interpretation of a targeted pre-existing musical text in its musical performance.

For Antichrist, the film-musical idea also involved recreating a pre-existing recording, in this case, Cecilia Bartoli's recording of Handel's ‘Lascia ch'io pianga’:

Lars wanted to use an existing recording of Cecilia Bartoli. But then we decided to make our own recording. I was responsible for the whole production of the recording, that is, for the choice of the location, the orchestra, and the singer. It's not that we couldn't get the Bartoli track! The new recording simply had the right expression with the slowed-down images and is very intimate. As I believe, the result turned out even better than it would have been with this existing recording.Footnote 63

Kristian Andersen, the music supervisor and composer for this project, told me they referred to the Bartoli recording during post-production. According to him, the recording had the ‘perfect’ tempo and rubato but would have been too ‘sweet’ and ‘majestic’ for the film.Footnote 64 In producing their own recording, they obtained more control over the musical expression, while copying the tempi and rubato from Bartoli's recording, by providing the concertmaster with an in-ear dynamic click track.

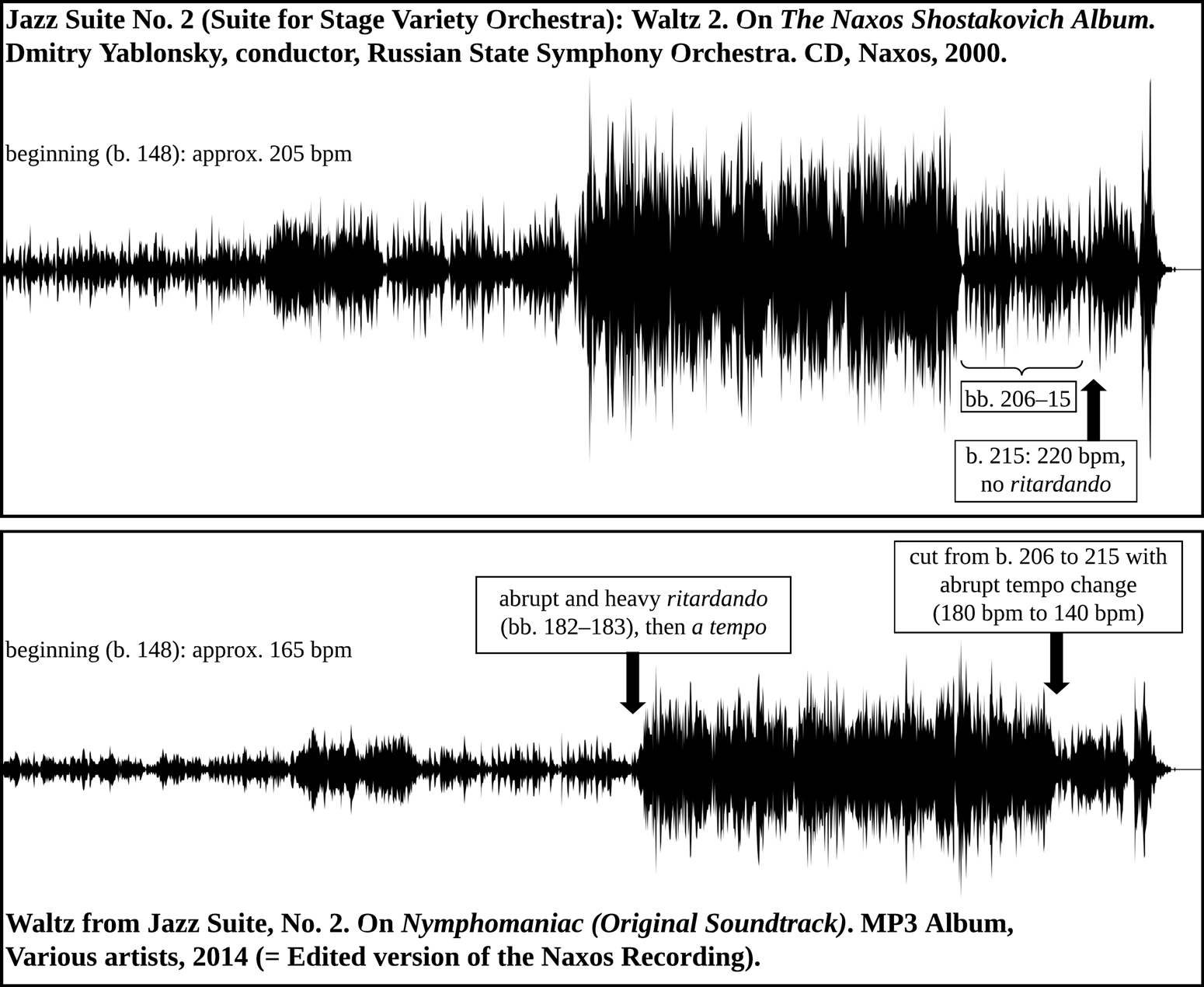

The recreation of a pre-existing recording can also consist of manipulating a different pre-existing recording: in Nymphomaniac, we hear Shostakovich's Waltz No. 2 several times. However, if we compare the final result on film with the credited pre-existing Naxos recording, there are numerous differences, especially regarding tempi (Figure 2).Footnote 65 The result of this audio time stretching resembles a different recording of this waltz by Decca in 1992, previously used in a television commercial for the French company CNP Assurances directed by Trier in 1993. This recording shows similarities to the edited version in Nymphomaniac. For example, the beginning of the trombone solo on the Decca recording, which corresponds to the beginning of the musical section in the film (b. 148), features almost exactly the same tempo (approx. 170 bpm) and ritardando (bb. 182–183). This modified self-quotation, in turn, produces an intertextual imitation. I therefore expanded my conception of the film-musical idea within the MIWG to encompass not only to abstract ideas regarding a musical work-concept when handling pre-existing music in general, but also concrete sonic realizations, and so the pre-existing musical recording in particular.

Figure 2 The editing of a pre-existing music recording.

Of course, the processes Trier's collaborators brought up in our interviews raise questions about how they might compare with productions by other (contemporary) directors who utilize pre-existing music. As a scholar with first-hand experience with how university departments of film and professional filmmakers work in reality, I have yet to find reason to believe that others operate differently. Although a comparative study of Trier's production processes with other perceived auteurs mélomanes lies beyond the scope of this article, the methodological approach outlined here means to provide more generalized tools for looking, and listening, to the many persons ‘behind the curtain’.

Concluding thoughts

Given how interviewees portray Trier as the sole filmic visionary and ultimate arbiter in their own descriptions of highly collaborative working processes, the statements I collected appear somewhat counterintuitive. My findings align with Macdonald's research experiences in developing his Screen Idea Work Group. These groups are not democratic communities, although they feature democratic elements overlaid on the conventional hierarchy of production. However, the Screen Idea is a levelling factor in the group's work, one that enables anarchistic processes within the established hierarchy:

Anyone from teaboy upwards could suggest an improvement that might have a significant bearing on the final screenwork, even if this contribution is eventually uncredited or filtered through the intervention of others. This kind of contribution informs but does not threaten the decision-making process, controlled or directed by the powerful within the group.Footnote 66

Macdonald paints the picture of a post-democracy inasmuch as nearly everyone can participate, although decisions are made by a select few. This participation does not challenge conventional institutional power structures. On the contrary:

Successful adoption of a contribution does not necessarily reflect the power structure, as all members of the group usually subscribe to some kind of consensus about the screen idea in question, and how it should operate. This means that any contribution to the screen idea is absorbed into the official hierarchy and conventional ways of working and – importantly – is (re-)directed towards the commonly understood goal of producing a particular (type of) screenwork.Footnote 67

My conversations with MIWG contributors affirm Macdonald's analysis. By portraying Trier as the driving force and person of ultimate vision, they reproduce a conventional hierarchy in film production culture. From their own statements, Trier admittedly influenced the musical design of his films significantly. However, it also became apparent to me that the real work processes are collaborative in nature, characterized by collective trial and error. The absorption of this collaborative dimension into the structural hierarchy marginalizes the work of many MIWG members, if not ignoring them altogether.

Compared with the idea of the auteur mélomane, the MIWG posits several changes in perspective for how we as scholars define their collaboration as such. The former corresponds to the reception, the latter to the realities of production; while the auteur mélomane understands film as a product, the MIWG focuses on the process; while the former implies film production as a functional autocracy (or auteurcracy), the latter exposes the democratic aspects of these working processes; and while the auteur mélomane pursues the attribution of individual authorship, the MIWG conceives of authorship collectively. As we have seen, these juxtapositions are only tendencies. We should resist proposing a conceptual opposition between the MIWG and the auteur mélomane, for in some cases the ideology of the auteur also shapes the thinking and actions of MIWG agents. Rather, both ways of thinking appear intertwined. We can see this ambivalence at play in Schepelern's answer to my question about what distinguishes Trier:

Lars is not an all-knowing genius. If he was interested in something, he would simply seek a conversation with an expert in the field and draw his information from it. What may distinguish him from others is his quick comprehension in such discussions. When Lars got the offer to stage Wagner's Ring at the 2006 Bayreuth festival, for instance, he asked me if he could talk to my father, Gerhard Schepelern, who was a respected conductor and probably the greatest opera connoisseur of his time in Denmark. After Lars backed out of the Bayreuth project, he published an article about his visions in which he quotes a sentence from my father. Both my father and I had the impression that with this one sentence he had understood what my father's life was all about: ‘The director must not try to be cleverer than the work!’Footnote 68

This is where the auteur mélomane and the MIWG meet: on the one hand, Schepelern highlights the importance of Trier's network; on the other, he re-emphasizes Trier's unique personhood, attributing a high level of comprehension to Trier in his deployment of experts. Directors such as Lars von Trier may be commonly understood as auteurs mélomanes, but their Musical Idea Work Groups nevertheless shape, and create, what we hear in ‘their’ films.