Doctors have a legal duty broader than that of any other health professional and therefore a responsibility to contribute to the effective running of the organisation in which they work, and to its future direction. 1 In an environment where their health and well-being is not prioritised doctors sometimes become ill, manifesting features of burnout and/or stress-related psychiatric disorders. Such psychiatric morbidity, or ‘caseness’, is detected using self-reported instruments such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli and Gureje2 Doctors also experience ‘burnout’, which is defined as a syndrome of exhaustion, cynicism and low professional efficacy. Reference Wu, Liu, Wang, Gao, Zhao and Wang3 Maslach et al described burnout as a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and stated: ‘What started out as important, meaningful, and challenging work becomes unpleasant, unfulfilling, and meaningless. Energy turns into exhaustion, involvement turns into cynicism, and efficacy turns into ineffectiveness’.

Increased prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and burnout has been established in studies from different parts of the world. A study of Italian physicians found an estimated prevalence of psychiatric morbidity to be 25%, and prevalence of burnout on the emotional exhaustion scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) to be 38.7%. Reference Renzi, Di Pietro and Tabolli5 Other studies have reviewed the factors associated with the development and maintenance of psychiatric illness and burnout among doctors. A survey of Australian doctors found that having medico-legal issues, not taking a holiday in the previous year and working long hours were all significantly associated with psychiatric morbidity. Reference Nash, Daly, Kelly, Van Ekert, Walter and Walton6 Self-criticism as a medical student was significantly correlated with psychological stress as a doctor in a cohort followed over 10 years by Firth-Cozens. Reference Firth-Cozens7

Burnout among doctors can lead to self-reported suboptimal patient care, Reference Shanafelt8 and to major medical errors. Reference Shanafelt, Balch, Bechamps, Russell, Dyrbye and Satele9 Psychiatric morbidity increases the likelihood of retirement thoughts and retirement preference. Reference Sutinen, Kivimäki, Elovainio and Forma10 Behavioural responses to burnout established in the literature also include alcohol and drug misuse, physical withdrawal from co-workers, increased absenteeism, arriving for work late and leaving early, and employee turnover. Reference Probst, Griffiths, Adams and Hill11 An extreme reaction to stress can be suicide, even though the pathway to this is complex and multifactorial. A UK survey of suicides between 1979 and 1983 ranked the medical profession as 10th in the list of high-risk professions. Reference Roberts, Jaremin and Lloyd12

Mental ill health can be found within every workplace in every country. In the UK the total cost to employers of mental health problems among their staff is estimated at nearly £26 billion each year: £8.4 billion from sickness absences and £15.1 billion from reduced productivity at work. 13 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) found that promoting the mental well-being of employees can yield economic benefits for the business or organisation, in terms of increased commitment and job satisfaction, staff retention, improved productivity and performance, and reduced staff absenteeism. 14 For the National Health Service (NHS) to reap the benefits described by NICE, priority should be given to employee mental health. However, the constant structural changes to the NHS in England have created instability and lack of job security within the public health workforce. Reference Griffiths and Thorpe15 The Health and Social Care Act of 2012 has placed doctors at the centre of clinical commissioning groups in charge of shaping services and made them responsible for £65 billion of the £95 billion NHS commissioning budget. 16 This imposes on doctors, especially general practitioners (GPs), a responsibility unlike any before, Reference Charlton17 one which their training has not prepared them for. The ability to cope with the challenges of working in the NHS and the possibility of stress and burnout were highlighted in the annual meeting of the British Medical Association in 2013, 18 and are the focus of this review.

Numerous research papers document burnout and stress-related psychiatric disorders in doctors worldwide, but none has presented the results in the form of a systematic review showing the prevalence and associated factors among UK doctors. The overall aim of this review was to redress this by assessing the prevalence of burnout and psychiatric morbidity among UK doctors working in different specialties, and to explore the associated identified factors. The objectives were to review the prevalence of the syndrome of burnout and psychiatric morbidity, to explore the nature of the relationship between burnout and psychiatric morbidity, and to identify other factors associated with the development and/or perpetuation of those conditions.

Method

Search strategies

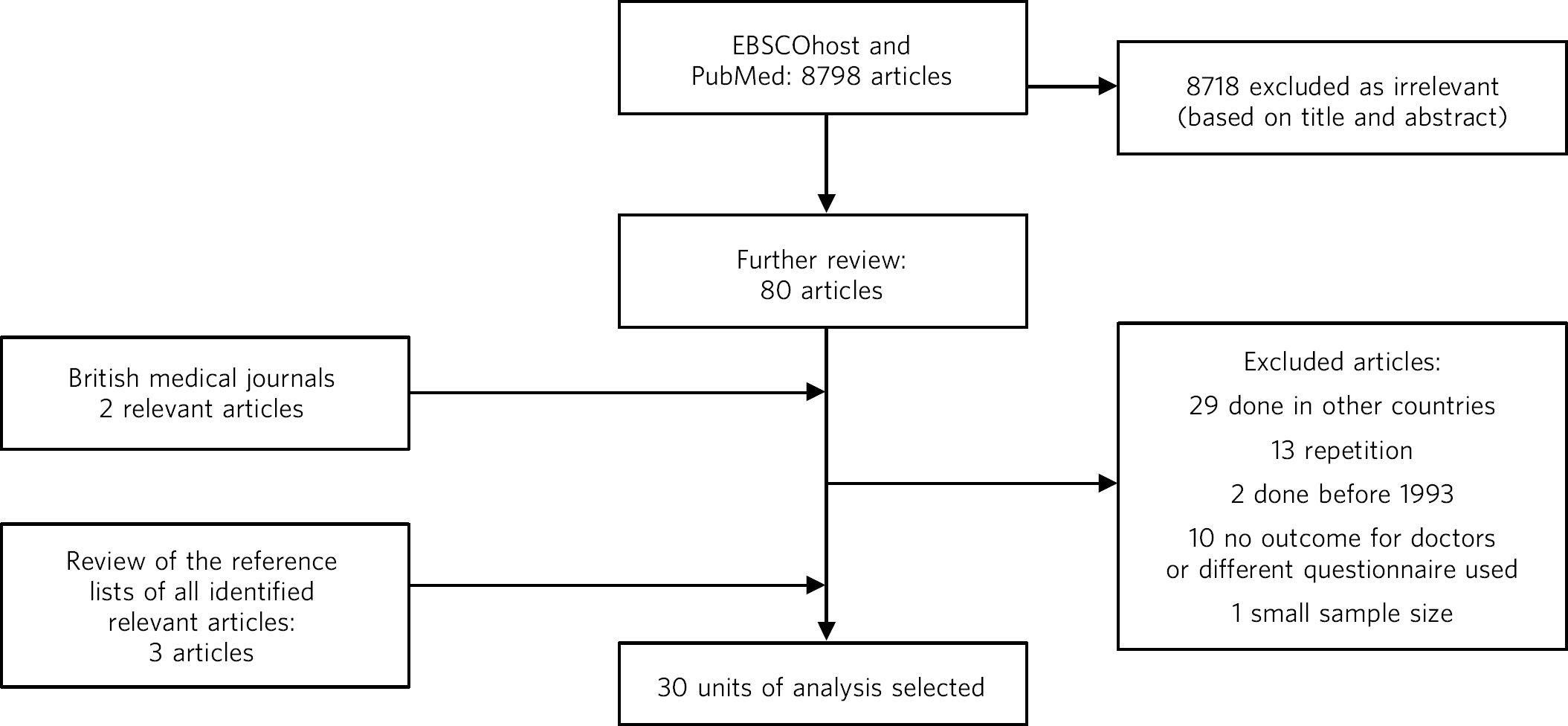

The words ‘burnout’ and ‘doctors’ were put into the search field of the EBSCOhost website specifying the following databases: Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES. Limiters activated were: English language, human, apply related words, and a time limit of January 1993 to December 2013. A total of 562 articles resulted from this, reduced to 489 automatically after duplicates were removed; 28 articles were selected for further analysis, and out of these 9 remained based on the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Using the same parameters but with the words ‘psychiatric morbidity’ AND ‘doctors’, a total of 97 articles were generated, reduced to 77 after the removal of duplicates, and from these only 1 was selected as new and appropriate. Again using the same parameters but with the words ‘stress’ AND ‘doctors’ NOT ‘nurses’, 3560 articles came up, reduced to 2259 after duplicates were removed; 23 new articles were reviewed in greater detail, and from these 5 new and appropriate articles were selected.

An advanced search on PubMed with the words ‘doctors’ OR ‘physicians’ AND ‘stress’, with a time limit of 1 January 1980 to 15 December 2013 and other limits (human, English language, clinical trial, journal article, reviews, lectures) generated 5973 articles. After careful analysis of the abstracts 28 new articles were identified for more detailed review, and from these 10 were selected as new and appropriate.

Two searches within the group of British medical journals with the phrases ‘burnout and doctors’ and ‘doctors and stress’ with the time limit of January 1993 to December 2013 yielded two new and appropriate papers.

A review of the reference lists of already-identified papers yielded three relevant papers.

Altogether, this extensive search yielded 30 relevant papers which were included in the units of analysis for this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the study selection process.

Inclusion criteria

Certain criteria had to be met before a study was included in the units of analysis:

-

(a) it had to answer any of the research questions

-

(b) for the measurement of the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity the study had to have used any version of the GHQ, and for the prevalence of burnout syndrome only the MBI was considered

-

(c) population group – only medical doctors in the UK irrespective of which organisation they work in

-

(d) minimum sample size of 50

-

(e) published between January 1993 and December 2013

-

(f) published in the English language.

The questionnaires

The GHQ is a well-validated and widely used screening tool for the detection of minor psychiatric disorders (psychiatric morbidity) in the general population. Reference Goldberg and Williams19 The GHQ-12 is self-administered and only takes about 5min to complete. It enquires about the experience of psychosocial and somatic symptoms in recent weeks. Each of the 12 items is measured on a 4-point Likert scale. Studies validating the GHQ-12 against standardised psychiatric interviews indicate that a cut-off score of 4 or above indicates a high probability that the individual suffers from a clinically significant level of distress (‘caseness’ or psychiatric morbidity).

The MBI is a 22-item self-report questionnaire, which is well recognised and widely used to measure burnout in relation to occupational stress. Reference Maslach and Jackson20 It has three subscales: personal accomplishment (measured by 8 items), depersonalisation (measured by 9 items) and emotional exhaustion (measured by 5 items). Responses are rated for each item according to frequency on a 7-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘every day’. The total score for each subscale is categorised ‘low’, ‘average’ or ‘high’ according to predetermined cut-off scores, based on normative data from a sample of American health professionals. A high degree of burnout is indicated by high scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation subscales and low scores on the personal accomplishment subscale.

Data extraction

A simple paper data extraction tool was created in Microsoft Word, and the tables from this have been used to portray the results in the results section. Data were extracted by the author over the months of November and December 2013.

Results

A total of 30 papers considered relevant and appropriate based on the study inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in this review. Table 1 summarises these papers.

Table 1 Units of analysis included in this review

| Study | Journal | Running head | Subspecialty/grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma et al (2008) Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson21 | Psycho-Oncology | Stress and burnout in colorectal and vascular surgical consultants |

Surgery/consultants |

| Ramirez et al (1996) Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22 | Lancet | Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and |

Surgery, gastro, oncology, radiology consultants |

| Wall et al (1997) Reference Wall, Bolden, Borrill, Carter, Golya and Hardy23 |

British Journal

of Psychiatry |

Minor psychiatric disorder in NHS trust staff: occupational |

Non-specific |

| Ramirez et al (1995) Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Cull, Gregory and Leaning24 |

British Journal

of Cancer |

Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians |

Oncology/consultants |

| Sharma et al (2007) Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson25 | Colorectal Disease | Stress and burnout among colorectal surgeons and | Surgery/consultants |

| Kapur et al (1999) Reference Kapur, Appleton and Neal26 | Family Practice | Sources of job satisfaction and psychological distress in |

GP, medical house officer |

| Guthrie et al (1999) Reference Guthrie, Tattan, Williams, Black and Bacliocotti27 | BJPsych Bulletin | Sources of stress, psychological distress and burnout | Psychiatry/non-specific |

| Benbow & Jolley (2002) Reference Benbow and Jolley28 |

International

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry |

Burnout and stress amongst old age psychiatrists | Psychiatry/consultants |

| Orton et al (2012) Reference Orton, Orton and Pereira Gray29 | BMJ Open | Depersonalised doctors: a cross-sectional study of 564 doctors |

GP |

| McManus et al (2002) Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30 | Lancet | The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK |

Non-specific |

| Kirwan & Armstrong (1995) Reference Kirwan and Armstrong31 |

British Journal

of General Practice |

Investigation of burnout in a sample of British general practitioners |

GP |

| Kapur et al (1998) Reference Kapur, Borrill and Stride32 | BMJ | Psychological morbidity and job satisfaction in hospital consultants |

Consultants/junior HO |

| Coomber et al (2002) Reference Coomber, Todd, Park, Baxter, Firth-Cozens and Shore33 |

British Journal

of Anaesthesia |

Stress in UK intensive care unit doctors | Intensive care/consultants |

| Applet on et al (1998) Reference Appleton, House and Dowell34 |

British Journal

of General Practice |

A survey of job satisfaction, sources of stress and psychological |

GP |

| Newbury-Birch & Kamali (2001) Reference Newbury-Birch and Kamali35 |

Postgraduate Medical

Journal |

Psychological stress, anxiety, depression, job satisfaction | Junior HO |

| Cartwright et al (2002) Reference Cartwright, Lewis, Roberts, Bint, Nichols and Warburton36 |

Journal of Clinical

Pathology |

Workload and stress in consultant medical microbiolo- gists |

Microbiology/virology consultants |

| Caplan (1994) Reference Caplan37 | BMJ | Stress, anxiety, and depression in hospital consultants, general |

Consultants (non-specific), GP |

| Burbeck et al (2002) Reference Burbeck, Coomber, Robinson and Todd38 |

Emergency Medicine

Journal |

Occupational stress in consultants in accident and emergency |

Emergency medicine/ consultants |

| Soler et al (2008) Reference Soler, Yaman, Esteva, Dobbs, Asenova and Katic39 | Family Practice | Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study | GP |

| Bogg et al (2001) Reference Bogg, Gibbs and Bundred40 | Medical Education | Training, job demands and mental health of pre- registration |

Pre-registration HO |

| Upton et al (2012) Reference Upton, Mason, Doran, Solowiej, Shiralkar and Shiralkar41 | Surgery | The experience of burnout across different surgical specialties |

Surgery/consultants |

| Sochos & Bowers (2012) Reference Sochos and Bowers42 |

The European Journal

of Psychiatry |

Burnout, occupational stressors, and social support in psychiatric |

Psychiatry, medicine/ senior HO |

| McManus et al (2004) Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43 | BMC Medicine | Stress, burnout and doctors' attitudes to work are determined |

Non-specific |

| Paice et al (2002) Reference Paice, Rutter, Wetherell, Winder and McManus44 | Medical Education | Stressful incidents, stress and coping strategies in the pre-registration |

Pre-registration HO |

| Tattersall et al (1999) Reference Tattersall, Bennett and Pugh45 | Stress Medicine | Stress and coping in hospital doctors | Non-specific |

| McManus et al (2011) Reference McManus, Jonvik, Richards and Paice46 | BMC Medicine | Vocation and avocation: leisure activities correlate with professional |

Non-specific |

| Deary et al (1996) Reference Deary, Blenkin, Agius, Endler, Zealley and Wood47 |

British Journal

of Psychology |

Models of job-related stress and personal achievement among |

Consultants |

| Thompson et al (2009) Reference Thompson, Corbett, Larsen, Welfare and Chiappa48 | The Clinical Teacher | Contemporary experience of stress in UK foundation doctors |

Foundation doctors |

| Berman et al (2007) Reference Berman, Campbell, Makin and Todd49 | Clinical Medicine | Occupational stress in palliative medicine, medical oncology |

Oncology and palliative medicine registrars |

| Taylor et al (2005) Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50 | Lancet | Changes in mental health of UK hospital consultants | Consultants |

GP, general practitioner; HO, house officer.

Findings on prevalence

Seven studies Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson21,Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Cull, Gregory and Leaning24,Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson25,Reference Guthrie, Tattan, Williams, Black and Bacliocotti27,Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30,Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50 had quantifiable data on the prevalence of both psychiatric morbidity and burnout (an in-depth analysis of studies reviewed in this paper is included in an online data supplement to this article). Altogether 22 studies reported on prevalence of psychiatric morbidity, and the range was 17–52% (average 31%). GPs and consultants had the highest scores. Fourteen studies had burnout scores, with nine reporting scores as percentages and five as mean scores; one study Reference Benbow and Jolley28 had both percentage and mean burnout scores. For emotional exhaustion the scores ranged from 31 to 54.3% and mean scores ranged from 2.90 to 31.26; for depersonalisation the scores ranged from 17.4 to 44.5% (1.95–15.68) and for low personal accomplishment the range was 6–39.6% (4.36–34.21). GPs, consultants and pre-registration house officers had the highest levels of burnout in the studies.

McManus et al, Reference McManus, Jonvik, Richards and Paice46 in a UK-wide study carried out in 2009, had the largest sample size at 2845 doctors and reported prevalence of psychiatric morbidity at 19.2%. The other two UK-wide studies with samples of over 1000 cutting across specialties and grades Reference Wall, Bolden, Borrill, Carter, Golya and Hardy23,Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43 reported psychiatric morbidity prevalence rates of 27.8% and 21.3%, respectively. Taylor et al Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50 reviewed 1308 consultants from different specialties and found the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity to be 32%.

One longitudinal study Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30 found no significant increase in the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity over 3 years in a non-specific group of doctors. Another longitudinal study Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50 found a significant increase in psychiatric morbidity and emotional exhaustion among consultants over 8 years.

The only European Union (EU) study looking at the prevalence of burnout in GPs from 12 EU countries Reference Soler, Yaman, Esteva, Dobbs, Asenova and Katic39 found lower average scores on all burnout scales compared with those of English GPs.

Findings on associated factors

Job satisfaction was found to be protective against the effect of stress on emotional exhaustion. The number of hours worked, job stress and overload were associated with increased psychiatric morbidity in eight studies. Two studies Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Burbeck, Coomber, Robinson and Todd38 found that women had significantly higher psychiatric morbidity than men, but three studies Reference Guthrie, Tattan, Williams, Black and Bacliocotti27,Reference Appleton, House and Dowell34,Reference Tattersall, Bennett and Pugh45 did not find any association with gender. The personality trait of neuroticism was significantly associated with increase in psychiatric morbidity in three studies, Reference Newbury-Birch and Kamali35,Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43,Reference Deary, Blenkin, Agius, Endler, Zealley and Wood47 while conscientiousness was a protective factor. Psychiatric morbidity was also positively associated with taking work home and with the effect of stress on family life.

Job satisfaction was negatively correlated with burnout in three studies. Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson21,Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson25 Age was an interesting factor; increased depersonalisation was found in younger doctors in five studies, Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson21,Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Guthrie, Tattan, Williams, Black and Bacliocotti27,Reference Orton, Orton and Pereira Gray29,Reference Kirwan and Armstrong31 whereas emotional exhaustion increased with age in two studies. Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Upton, Mason, Doran, Solowiej, Shiralkar and Shiralkar41 Being single was associated with increased burnout scores, and neuroticism increased burnout significantly in two studies. Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43,Reference Deary, Blenkin, Agius, Endler, Zealley and Wood47 Increased job stress and workload increased burnout in three studies, with significantly lower emotional exhaustion scores in part-time GPs.

Findings on the direct relationship between burnout and psychiatric morbidity

Three studies Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson25,Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30,Reference McManus, Jonvik, Richards and Paice46 found significant positive correlations between psychiatric morbidity as measured by the GHQ, and burnout syndrome. Using the process of casual modelling, McManus et al Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30 found that when scores were considered in 1997 and later in 2000, emotional exhaustion increased psychiatric morbidity, and vice versa. Personal accomplishment increased emotional exhaustion directly, and increased psychiatric morbidity directly but also indirectly through increasing emotional exhaustion. When other mental health problems were considered, anxiety and depression were found to increase psychiatric morbidity in three studies, Reference Newbury-Birch and Kamali35,Reference Caplan37,Reference Burbeck, Coomber, Robinson and Todd38 and depression increased depersonalisation. Reference Upton, Mason, Doran, Solowiej, Shiralkar and Shiralkar41

Discussion

The findings indicate that the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among UK doctors is quite high, ranging from 17 to 52%. This compares unfavourably with the results from a longitudinal survey of people living in private households within the UK, which found an 18-month period prevalence of common mental disorders to be 21%. 51 Only 4 of the 22 studies that reported on psychiatric morbidity found prevalence of less than 21%, Reference Kapur, Appleton and Neal26,Reference McManus, Winder and Gordon30,Reference Kapur, Borrill and Stride32,Reference McManus, Jonvik, Richards and Paice46 which is slightly better than 27% found in a study of palliative care physicians in Western Australia. Reference Dunwoodie and Auret52 An earlier study of junior house officers in the UK found psychiatric morbidity in 50% of doctors, Reference Firth-Cozens53 but this was in a period when the working pattern of junior doctors was relatively unregulated. More recent studies of junior doctors contained in this review found the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity to be around 19%. Reference Kapur, Appleton and Neal26,Reference Kapur, Borrill and Stride32 Concern over increasing prevalence of common psychiatric illnesses was borne out by the results from the study which found a 5% increase in morbidity among a cohort of consultants over an 8-year period. Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50

This review also found a high prevalence of burnout among UK doctors measured using the MBI. It lends further support to the growing body of evidence which has found the syndrome of burnout to be prevalent all over the world among health professionals. In a sample of Australian doctors, 24% suffered burnout; Reference Dunwoodie and Auret52 in a New Zealand sample of medical consultants one in five did; Reference Surgenor, Spearing, Horn, Beautrais, Mulder and Chen54 and in a cross-section of Japanese doctors 19% were affected. Reference Tokuda, Hayano, Ozaki, Bito, Yanai and Koizumi55 This review found even higher rates of burnout, with the prevalence of emotional exhaustion ranging from 31 to 54.3%, which would suggest UK doctors are comparatively more prone to burnout. GPs generally had higher scores for burnout, Reference Orton, Orton and Pereira Gray29 particularly in the study of European family doctors, Reference Soler, Yaman, Esteva, Dobbs, Asenova and Katic39 which found that the only countries in which GPs had higher burnout scores than England were Turkey, Italy, Bulgaria and Greece. Emotional exhaustion among a cohort of consultants was shown to have increased over an 8-year period, Reference Taylor, Graham, Potts, Richards and Ramirez50 with a prevalence of 41% in 2002.

This review has been able to pool together different studies which report on factors associated with the development and perpetuation of psychiatric morbidity and burnout. Neuroticism was positively and significantly correlated with psychological distress and burnout in three studies. Reference Newbury-Birch and Kamali35,Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43,Reference Deary, Blenkin, Agius, Endler, Zealley and Wood47 Neuroticism refers to a lack of psychological adjustment and instability leading to a tendency to be stress-prone, anxious, depressed and insecure, and it has been shown to negatively predict extrinsic career success. Reference Judge, Higgins, Thoresen and Barrick56 McManus et al, Reference McManus, Keeling and Paice43 in a 12-year longitudinal study on a cohort of students who started studying medicine in 1990, found that doctors who are more stressed and emotionally exhausted showed higher levels of neuroticism all through their careers. Neuroticism was also positively associated with perceived high workload. The researchers concluded that neuroticism was not only a correlate but a cause of work-related stress and burnout. Similar findings were noted by Clarke & Singh Reference Clarke and Singh57 in a study looking at the pessimistic explanatory style of processing information, which is a manifestation of neuroticism. In that study neuroticism was shown to positively predict psychological distress in doctors, and the authors recommended that susceptible doctors should be offered cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) to alter their explanatory style.

In an editorial titled ‘Why are doctors so unhappy?’ Richard Smith stated that the most obvious cause of doctors' unhappiness was that they feel overworked and under-supported. Reference Smith58 Job stress, feeling overloaded and the number of hours worked were positively linked to psychiatric ‘caseness’ and burnout in many of the studies in the present review, and this cut across specialties and grades. A General Medical Council (GMQ survey 59 of doctors in training found that 22% felt their working pattern leaves them short of sleep at work, and 59% said they regularly worked beyond their rostered hours. Increasing job stress without a commensurate increase in job satisfaction was associated with the presence of psychiatric morbidity, and job satisfaction was also positively correlated with illness in six of the reviewed studies Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson21,Reference Ramirez, Graham, Richards, Gregory and Cull22,Reference Sharma, Sharp, Walker and Monson25,Reference Appleton, House and Dowell34–Reference Cartwright, Lewis, Roberts, Bint, Nichols and Warburton36 Another significant finding was the correlation between psychiatric disorders and burnout, with the two feeding off each other, leading to worsening outcomes.

The public health importance of these findings cannot be overemphasised. GPs are at the frontline of healthcare delivery in the UK, and around 90% of all NHS contacts take place in primary care, with nearly 300 million GP consultations a year. 60 The estimated total number of GP consultations in England rose from 217.3 million in 1995 to 300.4 million in 2008, with a trebling of telephone consultations, and with the highest consultation rates among the growing population of elderly individuals. 61 Increased live births of over 110 000 over the past 10 years, 62 and an ageing population 63 have contributed to the pressure felt by services in general. However, in spite of the increased demand on primary care services, the proportion of the NHS budget that is spent on general practice has slumped to record levels, and GPs report that this has compromised the quality of care they can provide. 64 Under these circumstances, the added expectation from the UK Department of Health that GP surgeries should open for longer hours and should expand patient choice will undoubtedly lead to even more psychological distress and burnout among GPs.

A government-driven emphasis in the NHS on performance management and targets increases job demands and stress among managers, Reference Miller65 and increases psychiatric morbidity among doctors. The current climate of austerity in the UK, and the expectation that doctors should continue to provide high-quality care to patients within an NHS intending to make £20 billion worth of savings, 66 further expose doctors to burnout and stress. Psychiatrists are already having to deal with the expected increase in demand for mental health services stemming from the economic downturn, 67 and the increase in suicide rates 68 among the working-age population. Psychiatrists are particularly vulnerable to burnout, and patient suicide is a factor significantly associated with stress and burnout in this group Reference Fothergill, Edwards and Burnard69

Burnout among doctors can affect the entire public health workforce because as a syndrome it is considered ‘contagious’. Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter4 With the push for doctors to take up leadership positions at every level within the NHS a burnt-out doctor can negatively affect the entire healthcare delivery system. Unhealthy coping strategies in response to burnout and stress were identified in this review: these include retiring early, taking work home, taking it out on family, mixing less with friends, and avoidance, all of which work against the development of a healthy work-life balance.

Limitations

Some key limitations are worth highlighting. First, all the studies were cross-sectional surveys using questionnaires sent to the participants online or by post. Response rates varied, with some as low as 17%, and only in half of the studies was effort made to increase the response rate by sending reminders or repeat questionnaires. Non-response bias could have affected the results. Second, although the MBI was used in all the studies examining burnout, different versions of the MBI were utilised. With the GHQ some studies used the 28-item version but most used the 12-item version. The cut-off for ‘caseness’ using the GHQ also differed between studies and ranged between ⩾3 and ⩾5. However, these differences may not have significantly affected the overall findings given that a study to validate the two versions of the GHQ found no difference between them, and also established that the different cut-off for ‘caseness’ did not affect the questionnaire's validity. Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli and Gureje2

The cross-sectional method used for the surveys makes it difficult to draw a firm conclusion on the outcomes from a cause and effect perspective. Also, the number of potential confounders for the presence of burnout and common psychiatric disorders is vast and cannot be controlled for in surveys alone.

The fact that this literature review ends in 2013 may be considered a limitation, but the hope is that this paper will trigger more research in this area, and the author's intention is to update the literature review by 2023.

Recommendations

Doctors are ultimately responsible for the quality of care they provide at any time, and they need to be aware of their own vulnerability to burnout and psychiatric illness, and of their impact on patient care. Traditionally, doctors take pride in working a lot of hours, 70 and are 3 to 4 times less likely to take days off sick compared with other health professionals; 71 this combination is a recipe for burnout. A whole list of support networks is available on the GMC website, 72 and doctors should be encouraged to utilise these. However, there is a ‘culture of fear’ among doctors regarding the GMC, and 96 doctors, a lot of whom had mental health problems, have died by suicide since 2004 while being investigated by the GMC. Reference Dyer73 A lot more work is therefore needed to make the most vulnerable doctors feel supported.

At an organisational level, approaches designed to reduce the workload of doctors should be prioritised. Changes to doctors' contract of service should reflect an understanding of the impact of work-related factors on the health and well-being of doctors, and any such contract should contain the necessary protections to reduce the experience of psychiatric illness and burnout. The benefits of a healthy workforce on the quality of care provided in the NHS cannot be overstated.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.