25 January 2011. Police in the Suez open fire on anti-Mubarak protestors as they leave Midan al-Isaaf and head for the governorate building. By the early evening, several protestors have been killed in violent clashes with security forces. The next day, local residents and the relatives of the martyrs hold a demonstration outside of the Arbayeen district police station in the Suez. As the crowd swells to several hundred, police officers fire tear gas and birdshot in an attempt to disperse the demonstrators. Young men respond by letting off fireworks and throwing Molotov cocktails. By nightfall, the police station is on fire. 2 February 2011. A column of pro-Mubarak baltigiyya (approximately, thugs) approaches the Talaat Harb entrance to Midan al-Tahrir in downtown Cairo. An army officer confronts the thugs. Brandishing his pistol, he fires repeatedly in the air. When the thugs retreat, anti-Mubarak protestors rush to embrace the officer, chanting, “The army and the people are one hand.” Weeks later, large posters and banners depicting the scene are erected outside military bases and army checkpoints across the country. 22 November 2011. Protestors throw stones at a phalanx of soldiers, police, and Central Security Force (CSF) units stationed on Muhammad Mahmoud Street, a road leading from Midan al-Tahrir to the Interior Ministry. Security forces respond with volleys of tear gas and birdshot, while young men on motorcycles ferry wounded protestors to improvised field hospitals. Secular activists in the Midan confront a senior Muslim Brother, whom they denounce for selling out the Revolution for electoral gain. Fearing for his safety, the Muslim Brother withdraws from Tahrir. 30 June 2013. Uniformed police officers lead a protest march from outside of the Police Officers’ Club in Giza to Midan al-Tahrir, calling on the military to remove Islamist president Muhammad Mursi. The crowd of ostensibly civilian protestors wave Egyptian flags and chant, “The police and the people are one hand.” As large crowds continue to take to Tahrir, a retired Egyptian army general is interviewed on CNN, where he proclaims that 33 million Egyptians have taken to the streets to call for new presidential elections. 14 August 2013. Egyptian army bulldozers and heavily armed police take up positions around a Muslim Brother protest occupation in Midan Rabaʿa al-Adawiyya, a public square in Eastern Cairo. In the hours that follow, police and military personnel launch a sustained assault on the forty-seven-day-old occupation, killing over 900 protestors in what Human Rights Watch (2013) describe as “the most serious incident of mass unlawful killings in modern Egyptian history.” Five Snapshots of Contention

These vignettes of collective violence, mass mobilization, and repression are taken from the key moments and episodes of contentious street politics witnessed in Egypt since 2011. When read together, these snapshots encapsulate the empirical focus and explanatory task of this book: how an authoritarian regime came under sustained attack from below only to violently resurrect itself, and what this process can teach us about the prospects and legacies of contentious politics in the Middle East and North Africa after the Arab Spring.

This restoration was not inevitable. When Husni Mubarak resigned on 11 February 2011, following eighteen days of unruly and boisterous mass protests in the streets and squares of Egypt’s cities, many believed that a definitive rupture had occurred. Over subsequent months and years, however, a parlous and deeply flawed democratic transition, unfolding under the direction of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), revealed a new set of problems and ambiguities for Egypt’s self-styled “revolutionaries.” With military powers and old regime prerogatives still intact, the rapidly convened coalition of forces that had come together in Midan al-Tahrir and elsewhere divided, as narrow partisanship trumped coalition building.

The eventual triumph of the Muslim Brothers’ candidate Muhammad Mursi in the second round of presidential elections held in June 2012 seemed to presage a new institutional rubric in which the state apparatus would, at the very least, be brought under democratic control, but instead revived abiding anxieties and uncertainties about Islamist takeover and dictatorial intent. Two years after Mubarak’s removal, a second round of mass protests, this time against Mursi’s presidency, paved the way for a military coup that took place on 3 July 2013, precipitating an ongoing process of elite reconstitution that has since seen Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, a field marshal and former defense minister, installed as president in an elliptical return to Mubarak-style authoritarianism.

After a prolonged absence, the police fully redeployed to the streets of Egypt’s cities, better armed and more numerous than before, charged with enforcing a new protest law that criminalizes opposition to the military-backed government. In the year following the 2013 coup, security forces killed over 3,000 protestors, while tens of thousands of regime opponents were detained. The arm of Egyptian State Security tasked with monitoring Egypt’s Islamist movements and political dissidents, which was nominally disbanded following the 25th January Revolution, was formally reconstituted. A reinvigorated elite-level politics has not produced a model of governance responsive to protestors’ original demands for “ʿaīsh, hurriyya, ʿadāla igtimāʿiyya” (bread, freedom, social justice). Meanwhile, human dignity (karāma insāniyya), which sometimes replaces social justice as the third demand, continues to be routinely violated through the state’s use of torture and calibrated sexual violence against its opponents.

Against this backdrop of disappointments, reversals and retrenchments, the trajectories and legacies of the 25th January Revolution present important and interrelated puzzles for political sociologists and observers of the 2011 Arab Spring alike. How did Egyptians overthrow a seemingly well-fortified dictator of three decades in less than three weeks? How can we account for the position of the military during the eighteen days of mass mobilization? What explains the derailing of democratic transition in post-Mubarak Egypt? Why did the 25th January revolutionary coalition split? How did old regime forces engineer a return to authoritarian rule? How has repression shaped the possibilities for contentious collective action in post-coup Egypt? From a series of vantage points and seeking processual, agent-centered, and bottom-up explanations, this book shows that these puzzles, and the broader patterns of political change in post-Mubarak Egypt, can only be understood by paying close attention to the evolving dynamics of contentious politics witnessed in Egypt since 2011.

Egypt in a Time of Revolution

Was the 25th January Revolution a revolution? The answer to this question has important analytical implications for how we account for the events of January–February 2011 and what followed. On the one hand, a significant number of Egyptians certainly referred to it as such. My informants frequently prefaced their recollection of events with “fi ayām al-thawra…” (in the days of the revolution) or “fi waʾt al-thawra … ” (in the time of the revolution). Those who had joined the protests in Midan al-Tahrir and elsewhere were “thuwār” (revolutionaries).Footnote 1 Non-participants were members of “hizb al-kanaba” (the party of the sofa), while the revolution’s opponents were “al-nizām” (the regime), and later “al-filūl” (literally, the remnants [of the regime]). Protestors killed during the mobilization were “shuhadāʾ thawrat khamsa wa ʿishrīn yanāyir” (martyrs of the 25th January Revolution). This “revolutionary idiom” (Sewell Reference Sewell1979), replete with a chorus of jokes, put-downs, and internet memes, infiltrated newspaper coverage, television chat shows, and even the press releases issued by the SCAF in the year following Mubarak’s departure. Such a process of naming and narration was undeniably significant, not only in constituting the lived experiences of anti-Mubarak protestors (El Chazli Reference El Chazli2015), but also in legitimizing and authenticating protestors’ demands and expectations in light of the country’s revolutionary heritage (Sabaseviciute Reference Sabaseviciute2011; Cole Reference Cole and Gerges2014; see also Selbin Reference Selbin2010).

On the other hand, it seems much harder to justify an analytical categorization of “revolution” when reflecting on the trajectory of post-Mubarak politics, even given that the scholarly definition of what constitutes a revolution has expanded considerably in the past few decades. A new literature on contemporary revolutions argues that the revolutions of the late twentieth century onwards differ in several important ways from those that preceded them. If the classic model of a “social revolution” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979) involved protracted and frequently violent mobilizations to transform the social and economic order of semi-agrarian societies, today’s “revolutions” are found to be “negotiated” (Lawson Reference Lawson2005), “electoral” (Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2006), “non-violent” (Nepstad Reference Nepstad2011), “unarmed” (Ritter Reference Ritter2014), and at least nominally, “democratic” (Thompson Reference Thompson2003)Footnote 2 in their ethos. Contemporary revolutions are more urban and compact, lasting only weeks or months (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2013; Reference Beissinger2014), while the new measure of revolutionary “success” is increasingly the ousting of an incumbent authoritarian leader (Nepstad Reference Nepstad2011: xiv). According to this definition, revolutions are, therefore, more a “mode of regime change” (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2014), than a project of radical – political, social or economic – transformation (see Goldstone Reference Goldstone1991; Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001). As such, revolutions are increasingly seen as pathways to political liberalization, which strengthen rather than challenge the liberal international order (Lawson Reference Lawson2012: 12).

Scholars working in this vein have been quick to adopt the 25th January Revolution as evidence of this new modality of revolutionary action (Nepstad Reference Nepstad2011: xv; Beissinger Reference Beissinger2013: 574, Reference Beissinger2014; Lawson Reference Lawson2015; Ritter Reference Ritter2014). But despite several tentative parallels that can be drawn with the 25th January repertoire of contention, political developments in Egypt in the three years and more since Mubarak’s demise suggest that this designation was premature. Under the SCAF’s guardianship, the Mubarak-era state was never upended, and it remains resolutely intact today. Nor, as I will go on to show, did the 2011–2012 parliamentary and 2012 presidential elections in Egypt result in civilians exercising meaningful democratic control over the state. Given all this, it seems clear that no democratic or political revolution, even in the expanded analytical sense, can be said to have occurred.

So, what do I mean by the 25th January Revolution? According to my analysis, the eighteen days of the 25th January Revolution are better captured by the concept of a “revolutionary situation” (Tilly Reference Tilly1978: ch.7, Reference Tilly2006: ch.7; El-Ghobashy Reference El-Ghobashy2011) in which an alternative claim to sovereignty in the name of “the people” (al-shaʿb) formed the basis of a truly countrywide mobilization against the regime of Husni Mubarak. By revolutionary situation, I mean a conjunctural episode involving: “1) contenders or coalitions of contenders advancing exclusive competing claims to control of the state or some segment of it; 2) commitment to those claims by a significant segment of the citizenry; 3) incapacity or unwillingness of rulers to suppress the alternative coalition and/or commitment to its claims” (Tilly Reference Tilly2006: 159).Footnote 3 Egypt’s revolutionary situation was brought about by anti-police violence, mass mobilization in the country’s squares and main roads, and fraternization with the military – but it was never properly established and quickly subsided into a conventional democratic transition on 11 February 2011, following which constitutional and electoral forums came to structure a formal political process that unfolded under the direction of the military.Footnote 4

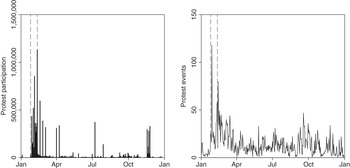

Despite the initial revolutionary situation in Egypt being quickly averted, revolutionary expectations and the new dynamics of contentious politics arising from the eighteen days of mass protest continued to structure, shape, and energize political life. In what was for many a “time of revolution,” Egyptians continued to mobilize. Figure 1.1 shows the frequency and size of contentious events in 2011. A massive strike wave by organized (and unorganized) labor, which began in the final days of the 25th January Revolution, was accompanied by local residents mobilizing across the governorates in a bid to achieve redress for their longstanding grievances (see Barrie and Ketchley Reference Barrie and Ketchley2016). There were even several episodes when the country appeared poised to return to a revolutionary situation: for instance, during the events of Muhammad Mahmoud Street in late November 2011, when protestors tried, unsuccessfully, to recreate the conditions of early 2011 and replace the SCAF with a civilian-led government.

These revolutionary aspirations were efficiently harnessed and redeployed on 30 June 2013, when both secular activists and old regime forces took to the streets in opposition to the divisive presidency of Muhammad Mursi. Egypt’s democratic transition failed three days later, on 3 July 2013, following the military coup. In the subsequent period, the revolutionary idiom of 2011 was superseded by a discourse of haybat al-dawla (awe of the state), employed to justify several regime-orchestrated massacres of pro-Mursi supporters, the detention of many of those who instigated the mobilization against Mubarak, and a new protest law. An anti-coup movement led by the Muslim Brothers launched daily street protests using a repertoire of contention evolving out of that employed in the 25th January Revolution. However, their efforts were quickly blunted by unprecedented repression, a fragmented political landscape (a consequence of the failed democratic transition), the anti-coup protestors’ refusal to take up arms, the tendency of Egypt’s poorest to equate protest with socioeconomic threat (Chalcraft Reference Chalcraft and Gerges2014: 179), and international and regional support for the consolidation of the military-backed regime.

Against this backdrop, thawrat khamsa wa ʿishrīn yanāyir (the 25th of January Revolution) remains commonly accepted shorthand in Egypt for referring to the eighteen days of popular protest that began on 25 January and which ended with the resignation of Hosni Mubarak. It is in this sense that I use it.

Contentious Politics

How can we place the 25th January Revolution, its trajectories and legacies within a broader scheme of social and political explanation? The heuristic adopted in this book is informed, most obviously, by the contentious politics literature associated with Doug McAdam, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly’s (Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001) Dynamics of Contention (DOC). That work sought to decompartmentalize the study of revolution, social movements, riots and other modes of transgressive collective action, and view them instead as belonging to a shared continuum of episodic, public and collective claim making. Under this common rubric, contentious politics is thus defined as “episodic, public, collective interaction among makers of claims and their objects when (a) at least one government is a claimant, an object of claims, or a party to the claims and (b) the claims would, if realized, affect the interests of at least one of the claimants” (Ibid.: 5).

Viewed in this mode, the 25th January Revolution, the post-Mubarak democratic transition and the anti-coup mobilization do not represent distinct processes or phenomena but can be understood by analyzing who is making claims, how those claims are made, the objects of those claims and regime responses to claim making. As Sidney Tarrow usefully sets out:

Within this arena, movements intersect with each other and with institutional actors in a dynamic process of move, countermove, adjustment and negotiation. That process includes claim making, responses to the actions of elites – repressive, facilitative or both – and the intervention of third parties, who often take advantage of the opportunities created by these conflicts to advance their own claims. The outcomes of these intersections, in turn, are how a polity evolves.

According to this perspective, the diverse ways in which Egyptians banded together to challenge the status quo are not simply manifestations of grievances to be explained, but were, in themselves, constitutive of the post-Mubarak political process. In this, to echo Dan Slater (Reference Slater2010: 5), to make sense of the patterns of political change in Egypt and the trajectory of the Arab Spring more broadly, we must account for “what contentious politics can explain in its own right.”Footnote 5

Here, my mode and manner of analysis is necessarily agentic and relational, treating “social interaction, social ties, communication and conversation not merely as expressions of structure, rationality, consciousness, or culture but as active sites of creation and change” (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001: 22). As Tilly (Reference Tilly2003: 5–8) notes, the conventional explanatory strategy pursued by social scientists has been to privilege either the ideas of participants, or their behavior. In contrast, “Relation people make transactions among persons and groups far more central than do idea and behavior people. They argue that humans develop their personalities and practices through interchanges with other humans, and that the interchanges themselves always involve a degree of negotiation and creativity” (Ibid.: 5–6).Footnote 6 In the empirical chapters that follow, I use this insight to develop a conjunctural and interactive account of the 25th January Revolution and the post-Mubarak political process, grounding my explanation in a series of relationships: between collective violence and nonviolent activism, protestors and security forces, elections and contentious collective action, elites and street protest movements, and repression and mass mobilization. In doing so, I show how a relational ontology can be employed to interrogate several key assumptions of the literature on civil resistance, emotions, democratization, authoritarian retrenchment, and repression.

Before then, a digression on one of the key analytical concepts that structures this book and its argument is germane. In the argot of the contentious politics literature, the ways in which Egyptians make claims is constrained by the available “repertoire of contention.” Tilly (Reference Tilly1977) first introduced the “repertoire” metaphor to describe the evolving subset of protest tactics used in France between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries. This drew on one of his earliest and arguably most productive insights (Reference Tilly1978: ch.6): that when people act collectively, they only do so in a limited number of ways. Expanding upon this in later works, Tilly argued that:

Repertoires are learned cultural creations, but they do not descend from abstract philosophy or take shape as a result of political propaganda; they emerge from struggle. People learn to break windows in protest, attack pilloried prisoners, tear down dishonored houses, stage public marches, petition, hold formal meetings, organize special-interest associations. At any point in history, however, they learn only a rather small number of alternative ways to act collectively. The limits of that learning, plus the fact that potential collaborators and antagonists likewise have learned a relatively limited set of means, constrain the choices available for collective interaction.

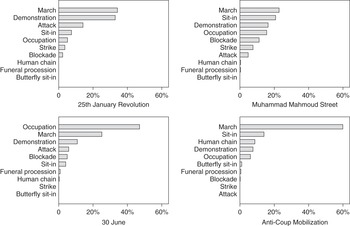

Michael Biggs (Reference Biggs2013: 408–409) has reformulated Tilly’s stance into two interrelated propositions: “repetition is far more likely than adoption; adoption is far more likely than invention.” In Egypt, in the period between 2011 and 2014, the repertoire of contention was highly repetitive. This is well captured in Figure 1.2, which classifies protest events by their tactics during the eighteen days of the 25th January Revolution, the events of Muhammad Mahmoud Street, the 30 June protests, and the anti-coup mobilization. Four tactics – occupations, sit-ins, demonstrations, and marches – predominated, and were used in over 75 percent of protest events in each episode.

Just as the dynamics of mobilization in Egypt were constrained by the available modalities of claim making, they were also delimited by the spaces and ecologies of protest (see Sewell Reference Sewell and Aminzade2001; Tilly Reference Tilly2000). During the first days of the 25th January Revolution, a powerful and easily replicable model for mobilization emerged in Cairo that then diffused throughout Egypt and then other Arab Spring countries: protestors left designated mosques following prayer to join up with other protestors in public squares and main arterial roads. Mubarak’s ousting on 11 February 2011 underlined the efficacy (and legitimacy) of this model, leading to its emulation by a multitude of other political actors in the years that followed, including old regime holdovers, Islamists, local residents, and workers in Egypt and beyond (e.g., Ketchley Reference Ketchley2013; Reference Ketchley2016). With time, security forces adapted to protestors’ tactics and their use of space by targeting key nodes in the spaces of contention. How protestors responded to these countermeasures, and the implications of regime learning for future episodes of mass mobilization in Egypt, will be a topic for later chapters.

Repertoires are, in turn, related to the broader political process. In line with Tilly’s (Reference Tilly2006) expectations, the Egyptian repertoire of contention delimited the possibilities of popular politics: this process was shaped by, and in turn shaped, the Egyptian political regime; especially the regime’s degree of democratic participation and its capacity to police dissent. A powerful illustration of this approach is presented in Tilly’s (Reference Tilly1995; Reference Tilly1997) work on popular contention in Great Britain. Tilly showed that by the late eighteenth century the increasingly visible role of elections and parliament in organizing public life led to the “parliamentarization of contention,” meaning that parliament became an object of contention. This shift was in turn inflected in the means and timings of contention. Marches, demonstrations, petitions, and rallies began to revolve around single issues and parliamentary debates. Short term objectives previously achieved by violent means were replaced by longer-term struggles and associational activities structured around the rhythms of parliamentary life.

In contemporary Egypt, we see an accelerated version of a process not dissimilar to that described here by Tilly. The demobilizing pressures of the post-Mubarak democratic transition saw certain movements pursue more routine, procedural politics as a consequence of a shift in the sites of claim making – from the contentious street to the chambers of a parliament – as the initial revolutionary situation folded into a more conventional democratic breakthrough (see also Robertson Reference Robertson2010: ch.6). Other movements and groups, however, continued to pursue their goals through the streets. Explaining this divergence, and its implications for the 25th January revolutionary coalition, will be a key task in the discussion to come.

Methods and Data

To chart the dynamics of contentious politics that emerged from the 25th January Revolution, this book draws on over two years of fieldwork, involving multiple research trips, carried out in Egypt between 2011 and 2015. It marshals several different types of evidence, including event data, fatality data, informant testimony, newspaper articles, video footage, and still photography. In the following section, I briefly summarize my data collection methods, while considering several strategies for combining and triangulating different kinds of qualitative and quantitative data to study contentious collective action in Egypt and beyond.

Event Catalog

An event catalog is a “set of descriptions of multiple social interactions collected from a delimited set of sources according to relatively uniform procedures” (Tilly Reference Tilly2002: 249). Event catalogs have a long history in the study of contentious politics (e.g., Tilly, Tilly and Tilly Reference Tilly, Tilly and Tilly1975; Tilly Reference Tilly1995), with data usually drawn from newspapers, journals, and periodicals. The event catalog from which I draw contains detailed information on 8,454 protest events, and encompasses the 25th January Revolution, the first year of the post-Mubarak democratic transition, the anti-Mursi mobilization, and the first six months of the post-coup period. It primarily derives from protest reports published in four Egyptian national newspapers, al-Masry al-Youm, al-Dostor, al-Shorouk, and the Muslim Brothers’ Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) newspaper, al-Hurriyya wa-l-ʿAdala. Drawing on multiple sources helps to address known problems of underreporting, fact-checking, and cross-referencing in event catalogs drawn from newspapers (e.g., Franzosi Reference Franzosi1987; Maney and Oliver Reference Maney and Oliver2001; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Martin, McCarthy and Soule2004). I also compared newspaper reports to videos of protests uploaded to social media, as well as human rights reporting of repression. Taken together, this data allows for the first systematic account of Mubarak’s overthrow and what came afterwards. The source material, data verification, coding strategies, and variables for the event catalog are summarized in the appendix.

Interviews

As well as collecting comprehensive protest event data, I also conducted eighty semi-structured interviews in both Arabic and English. Since protestors are a relatively closed population, my primary method for selecting informants was snowball-based sampling. I aimed to conclude every interview by asking my informants whether they could introduce me to anyone who they thought could contribute to my research. I also conducted targeted interviews in which I approached individuals who had a public biography that made them of interest. I conducted follow-up interviews on several occasions. I have also drawn on interviews conducted through personal correspondence with protestors and activists who were not available for face-to-face interviews.

With regard to citing testimony and considerations of anonymity, I made it clear to informants that I would use only their first names. This was due to the risks informants face when speaking to foreign researchers on sensitive topics such as the police, the military, or the Muslim Brothers. Because of the frequency of certain names, I have used a single digit to distinguish between informants, e.g., Abdullah 1, Abdullah 2, and Abdullah 3. On several occasions when conducting interviews with established political figures, I gained consent to use the informant’s full name. When informants asked to be quoted anonymously, I have referenced testimony by the informant’s role, e.g., “interview with Muslim Brother” or “interview with Journalist.”

Video and Photographs

Within hours of protestors reaching Midan al-Tahrir, on 25 January 2011, still photographs and video footage uploaded to social media sites had already come to constitute a searchable digital archive. The digitization of social processes and the ubiquity of camera-equipped mobile phones present new opportunities to study contentious politics. I assembled a photographic and video archive of protest events in Egypt from internet-based searchesFootnote 7 and the personal “archives” that informants had saved on mobile phones, memory sticks, and hard drives. Video footage and still photographs uploaded to social media frequently had time stamps were uploaded shortly after the event that they captured, or included captions providing additional context,Footnote 8 while visual materials obtained from informants were accompanied by detailed commentaries of the events in question.

Of course, video footage and still photographs have limitations. Both show events in Egypt in real time, and thus one never sees the political process directly.Footnote 9 Instead, the macro is constructed through concepts and metaphors. This requires large amounts of data with snippets of contentious claim making sutured together to give a sense of the larger repertoire. With this kind of detective work, video footage and still photographs allow us to view dimensions of contentious episodes in Egypt that might otherwise fall beneath the threshold of historical visibility. We also get a very different perspective on how protests unfolded. Captured in real time, contention appears unruly and emotional, with micro-interactions appearing to be formative in explaining situational outcomes (Collins Reference Collins2008).

The Structure of the Book

The chapters that make up this book consider both the causes and the consequences of Mubarak’s removal at the hands of irrepressible “people power.” In this, I follow a tripartite periodization of Egyptian politics, covering the eighteen days of mass mobilization, the democratic transition, and the post-coup period.

This introductory chapter is followed by a chapter that focuses on the first three days of the 25 January Revolution. When protestors outmaneuvered Interior Ministry-controlled CSF units to reach Midan al-Tahrir on 25 January 2011, they triggered protests in the streets and squares of Egyptian cities across the country. Scaling participation rates from the Arab Barometer’s (2011) survey up to the total population suggests that over 6 million Egyptians took to the streets over this period (Beissinger, Jamal, and Mazur Reference Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur2015: 23). Other scholarly studies, citing journalists’ and informants’ estimates, put that number even higher – between 15 and 20 million anti-Mubarak protestors (e.g., Gunning and Baron Reference Gunning and Baron2013: 164). This chapter questions these figures. Using the event catalog, it suggests that protest participation was probably considerably smaller than is currently assumed, and that the largest protests occurred over a week after the mobilization began. While this finding seems to confirm Lichbach’s (Reference Lichbach1995) rule that no more than 5 percent of a national population mobilizes at any one time, it does problematize how protest scaled-up and overcame Mubarak’s national security state. Chapter 2 takes up this puzzle, shedding light on a wave of anti-police violence that peaked on 28 January, and which led to the routing of a key wing of Mubarak’s repressive apparatus, and thus helping to bring about a revolutionary situation. Here, the chapter problematizes accounts of the 25th January Revolution that stress the singular efficacy of nonviolent contention in bringing about Mubarak’s overthrow, pointing instead to a dynamic interplay between collective violence and nonviolent contention during the critical early phase of the mobilization.

With a view to explaining the military’s role during the 25th January Revolution, Chapter 3 picks up events on the early evening of 28 January. Using video evidence, still photographs, Egyptian newspaper reports, and informant testimony, it develops a focused account of the micro-interactive dimensions of protestor-soldier relations that developed in and around Midan al-Tahrir. The practices that came out of these encounters, this chapter shows, were situational and should be understood vis-à-vis an improvised fraternization repertoire that made immediate, emotional claims on the loyalty of regime forces. Fraternization contained military opposition to the mobilization and the possibilities for protestor-soldier violence through the forging of a precarious solidarity, which was later appropriated by the SCAF to legitimize its assumption of executive powers in the post-Mubarak democratic transition.

Turning to the post-Mubarak democratic transition, Chapter 4 draws on interviews with Muslim Brothers, the movement’s publications, and the event catalog. It begins by considering the part played by the Muslim Brothers in the 25th January Revolution and the nature of the revolutionary coalition that emerged in Egypt’s streets and squares. It then spotlights the Brothers’ demobilization and privileging of electoral and constitutional forums in the first eighteen months of the transition. The chapter explores how the Brothers’ decision to sit out further protests to focus on elections facilitated the breakup of the revolutionary coalition that had ousted Mubarak and insulated the SCAF from street-level mobilization, leaving bad legacies for Mursi’s year in office.

Chapter 5 considers the events leading up to the 3 July 2013 coup. On 30 June 2013, massive protests were held in Midan al-Tahrir and outside the presidential palace calling for early presidential elections and the resignation of elected Islamist president Muhammad Mursi. Smaller protests were held in the governorates. Drawing on informant testimony, video footage, newspaper accounts, and event data, this chapter finds the 30 June protests to be problematically rule-bound, with security forces dictating the sites and targets of protest. Here, the chapter shows how the army and the police, in ways reminiscent of “elite-orchestrated” protest in other contexts, facilitated and then co-opted the 30 June protests that would pave the way for Mursi’s removal and a full blown return to military rule.

The final substantive chapter maps the patterns of mobilization and demobilization after the 3 July 2013 coup. Chapter 6 begins by examining the Muslim Brothers’ decision to counter-mobilize in the weeks before the coup. Drawing on interviews with leading Muslim Brothers and anti-coup activists, it traces the origins of the anti-coup movement to a decision in December 2012 by the Muslim Brothers to establish a street presence to defend Mursi’s presidency, and considers the events leading up to the 3 July coup, the Brothers’ strategy of occupying public squares, and the formation of new “against the coup” movements. Using event data and informant testimony, the chapter then charts how the repertoire, sites, and timings of anti-coup contention were transformed by repression following the killing of over a thousand anti-coup protestors of 14 August 2014.

A concluding chapter summarizes the book’s findings and considers several unresolved questions and silences in the study of contentious politics, the 25th January Egyptian Revolution, and the Arab Spring.