In a 1971 countywide referendum, residents of Durham, North Carolina, overwhelmingly opposed the merger of the city and county school districts, two public school systems that had operated separately since the 1880s.Footnote 1 The question of merging the two systems had surfaced in 1958 and 1968, but voters in both areas had rejected it.Footnote 2

At the time of the 1971 referendum, the Durham city schools had a predominantly black student body, and the local press often pointed to issues of low achievement and poverty in the city district. Although Durham as a whole was known for its thriving black businesses and politically powerful black middle-class, many city residents lived in impoverished black neighborhoods, and continuously fought to improve living conditions, economic and educational opportunities. Poor black residents in Durham had actively mobilized during antipoverty campaigns in the 1960s.Footnote 3 The county schools, located in the surrounding suburbs and in isolated pockets inside the city limits but outside of the city school system, were predominantly white, and increasingly overcrowded.Footnote 4

Historian Jean Bradley Anderson interpreted Durham's segregated landscape as a direct result of “white flight” following school desegregation in the region.Footnote 5 Although token desegregation began in Durham in 1957, white resistance prevented full-scale desegregation until 1970.Footnote 6 As in many metropolitan areas in the country, white residents, incentivized by housing, transportation, and school policies, purchased homes in the suburbs in massive numbers.Footnote 7 This migration often meant that white children would attend predominantly white schools that did not fall within the scope of desegregation plans. The 1973 Milliken v. Bradley Supreme Court decision limited the possibility of cross-district desegregation, since remedies in these cases could not include districts that had not engaged in intentional segregation as proven in court.Footnote 8

In 1992, the Durham's two districts eventually merged without a referendum.Footnote 9 How? Looking at the history of public opposition to the merger in Durham makes 1992 a surprising turn of events, and an unusual case at a time when many suburban areas that had previously been part of a single, countywide district were seceding from urban districts.Footnote 10 The impulse for the merger came from the Board of County Commissioners, the governing body responsible for allocating state and federal budgets to both school districts, which otherwise operated independently.Footnote 11 Chairman of the Board of County Commissioners William V. Bell believed that the city could never be as attractive as its neighbor Raleigh, given the violence, overcrowding, and low test scores that plagued its inner-city schools.Footnote 12 The state legislature passed the merger in July of 1991, despite vocal opposition from residents in the city and county districts.Footnote 13

Much of the city's opposition to the merger stemmed from a fear of diluted black political influence under a merged system, even though the merger seemed to be the only way to equalize resources between the two districts. This tension between seeking equal resources and maintaining political power for the city school district existed and persisted because of historical, structural injustices in school financing schemes, legal constraints, and other policies that reinforced inequalities between urban and suburban areas. Scholars who have documented this paradox argued that desegregation policies came at a greater cost for black administrators, teachers, families, and students.Footnote 14 This article examines the evolution of these dynamics beyond the desegregation years. The constant tension between financial equity and political power, and the changing economic interests that came with the increased influence of the business community, shaped the merger story in Durham. This article builds on recent scholarship about the influence of private-sector actors such as businesses, universities, and urban planners in the history of urban education.Footnote 15 It explores how various actors’ understanding of the implications of integration or segregation on the economic attractiveness of Durham changed over time. The unique political context of Durham, and especially the strength of the city's black political elite, leads us to examine the role of schools in shaping political alliances.

At several moments in time, in 1958, 1968, 1971, 1988, 1991, 1996, referenda and bond issue votes show how the competing interests of different Durham residents clashed over the question of whether or not the two districts should merge. To date, historical accounts of the Durham merger have focused on the racial battles between the predominantly black city district and the white suburban district, and “white flight” in these narratives appears strictly as the racist choice of white residents to relocate away from increasingly black schools.Footnote 16 Moving beyond this narrative, I explore a contentious political situation that developed in the context of a pernicious school financing structure and the changing context of economic-development policies.

Eventually, in 1991, a political alliance between business leaders, county commissioners, and the legislature in Durham managed to bypass the strong resistance that characterized public opinion about the merger, and which crystallized on racial conflict. This article explores how this coalition developed, and why previous attempts could not garner sufficient support. It also highlights continued local concerns over racial representation on school boards and the legacy that previous policies still hold on Durham's educational landscape.

Maintaining a Dual School System: 1958–1968

From 1958 to 1968, official policies ensured school segregation in Durham, and merger attempts between the city and county schools failed twice, at a time when the city schools were considered of better quality.Footnote 17 Growth in Durham's overall population brought the question of merging the county and city school systems to the fore in 1958 as city schools, both black and white, were becoming overcrowded.Footnote 18

Segregation was part of the conversation but took the form of guarantees that a merged system would still provide “opportunities to operate a segregated system.”Footnote 19 In 1958, four years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, substantial desegregation in Durham seemed unfathomable.Footnote 20 Engaged in mass resistance, the white population and white leadership fiercely opposed desegregation and devised assignment plans that preserved the racial status quo.

Support for the merger had come from the Board of County Commissioners, which was concerned about the financial efficiency of operating two separate systems, especially as the city grew in size and population.Footnote 21 The League of Women Voters supported the merger as well and emphasized the economic benefits of a merged system, stating, “The Durham community—City and County—would be a more attractive area to new people and industry looking for a home.” A member of the League of Women Voters drew a triangle next to this statement, with the letters “RT,” referring to the Research Triangle area.Footnote 22 Merger supporters already tied the merger to ideas of economic development, as they would in later years, but the argument did not garner enough political support to implement change.

The merger question was attached to a bond issue in November 1958, which was defeated by a ten-to-one margin.Footnote 23 In fact, the question of taxes dominated the merger debate that year, as combining the two entities would have triggered a forty-cent increase on each one hundred dollars for county schools in order to match the supplemental city tax.Footnote 24 City schools seemed to fare better than the county schools, and the city school board was unwilling to concede control of the city system. County residents resisted the tax.

The themes of segregation, economic development, and taxes would remain central to merger debates for three decades, but the evolving context of Durham changed the framing of these issues. During the 1958 to 1968 decade separating the two crucial votes in Durham, there was much talk about the role of segregation or integration for the economics of the South, but political and business interests at the local scale failed to align.Footnote 25

In 1968, a bond proposal ignited heated debate once again. Education had changed in Durham since the previous merger attempt, and many affluent families had moved to the suburbs in fear of court-mandated desegregation. This reduced the tax base for the city schools. A committee of the interracial Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance advocated for the merger and explicitly criticized the property tax system because it deepened inequalities: “It is imperative that the city and county school systems be consolidated. … It is necessary for city and county government groups to enlarge the tax base by means other than the traditional one of increasing the property tax, to assure adequate financing.”Footnote 26

The system of school financing created a vicious cycle: as the city's tax base decreased, the city needed to increase its tax rate, which could drive people away. Two Durham residents wrote to the city's Board of Education to highlight this issue:

I am a white person, a social worker by profession. My husband is a psychology professor at Duke. Both of us are concerned about the decline of our cities, which are quickly becoming negro slums. The approval of yesterday's bond issue would have added to the exodus of affluent whites to the county, where they could attend the shiny, new, segregated schools.Footnote 27

The bond issue failed because it proposed a tax increase.Footnote 28

Business leaders involved in Durham's economic development supported the merger. George Watts Hill, a high-profile businessman who was instrumental in creating the Research Triangle Park (RTP), a scientific hub that would later bring tremendous economic growth to the region, was extremely disappointed with the 1968 failure and wrote to the Durham City Board of Education: “If three systems can be merged in Gaston County and a $20 million bond issue approved, it would seem to me that the least Durham could do would be to put two systems together and approve a reasonable bond issue.”Footnote 29 Hill was also a proponent of school integration and believed that segregation hindered progress in the South. He tied racial harmony, or the pretense of it, to greater attractiveness for the region.Footnote 30 Many business leaders in Durham would continue to support the merger for decades to come, although the industrial landscape had changed, and economic incentives revolved on a different understanding of development in later decades.

The February 1968 defeat of the school bond issue prompted the Division of School Planning of the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction to look into the Durham districts.Footnote 31 The state agency asked the two districts to form a study group.Footnote 32 Representatives from the city and county boards sat on the study group and examined operations, planning, finance, student assignment, and school construction. The fact that the study group was all white raised serious concerns about black representation and called the group's recommendations into question.Footnote 33 Department of Public Instruction official J. L. Pierce was astounded by the level of disagreement in Durham and pointed out to the Durham School Consolidation Study Committee, which included city and county boards as well as the county commissioners, that representatives from the two districts were not ready to make any common decisions, not even on the composition of the study group itself.Footnote 34 The study committee did not lead to palpable changes, but it built momentum for a merger proposal three years later.

Curtailing Desegregation: 1971–1988

In 1971, the Board of County Commissioners again pushed for a referendum, with support from several groups highlighting the economic rationale behind the merger, including the Chamber of Commerce and faculty at Duke University.Footnote 35 But once again the Durham population overwhelmingly opposed the proposal and chose to maintain the boundaries between the urban and suburban districts. The three years that separated the 1968 and 1971 referenda had witnessed drastic changes in Durham, marked by court-mandated desegregation that overhauled the schools, with new assignment plans implemented in 1970.Footnote 36

During the height of desegregation, from 1971 to 1974, the merger of the county and city school was again struck down—by vote, by the school boards, and by the courts. Schools began to resegregate almost as soon as the desegregation plan was implemented. For example, at Hillside, the historically black high school, black students represented 69 percent of the student body in 1970 when the plan was implemented and 78 percent in 1973.Footnote 37

The 1971 referendum had a salient racial dimension. Press coverage highlighted the racial implications of the merger vote, which, as the Carolina Times argued, would trigger white outmigration, and in the context of racial discrimination, would run the risk of diverting resources away from the city schools: “Without merger, the city school system will soon become an almost totally black system. … The ensuing racial imbalance will nullify any educational improvements gained by Durham blacks, and end in an erosion of city school educational standards.”Footnote 38 The implications of the merger defeat, then, were clear, and the school districts would gradually become more segregated, not as a dual system within school district boundaries, but as two separate entities—one predominantly white, and one black.Footnote 39 In the early 1970s, Durham city's population was approximately 50 percent black and 50 percent white, and the county's population was 86 percent white.Footnote 40

The issues that segregation raised in terms of tax base and resources were even more patent in racially segregated enclaves called the “city out” areas, which existed within the city boundaries but were operated by the county school system. As the City of Durham grew, residents in the areas within the expanded city boundaries had the opportunity, once the areas were officially annexed by the city, to choose whether to be attached to the city or county school system.Footnote 41 This was possible because the city had voted a supplemental tax for schools in 1932, which created a fiscal discrepancy between the city and county districts. Starting in 1932, then, areas annexed into the city of Durham were not automatically annexed to the city school district. Residents of the annexed areas could vote to remain part of the county school district, thereby avoiding the city supplemental tax.Footnote 42

Until 1955, all annexed areas were incorporated into the city school district even though the city's supplemental school tax was twice as much (forty cents per $100 valuation in the city versus twenty cents in the county district).Footnote 43 Starting in 1955, notably a year after Brown v. Board of Education, this pattern was abruptly interrupted, and expansion of the Durham city limits only rarely translated into school city district inclusion.

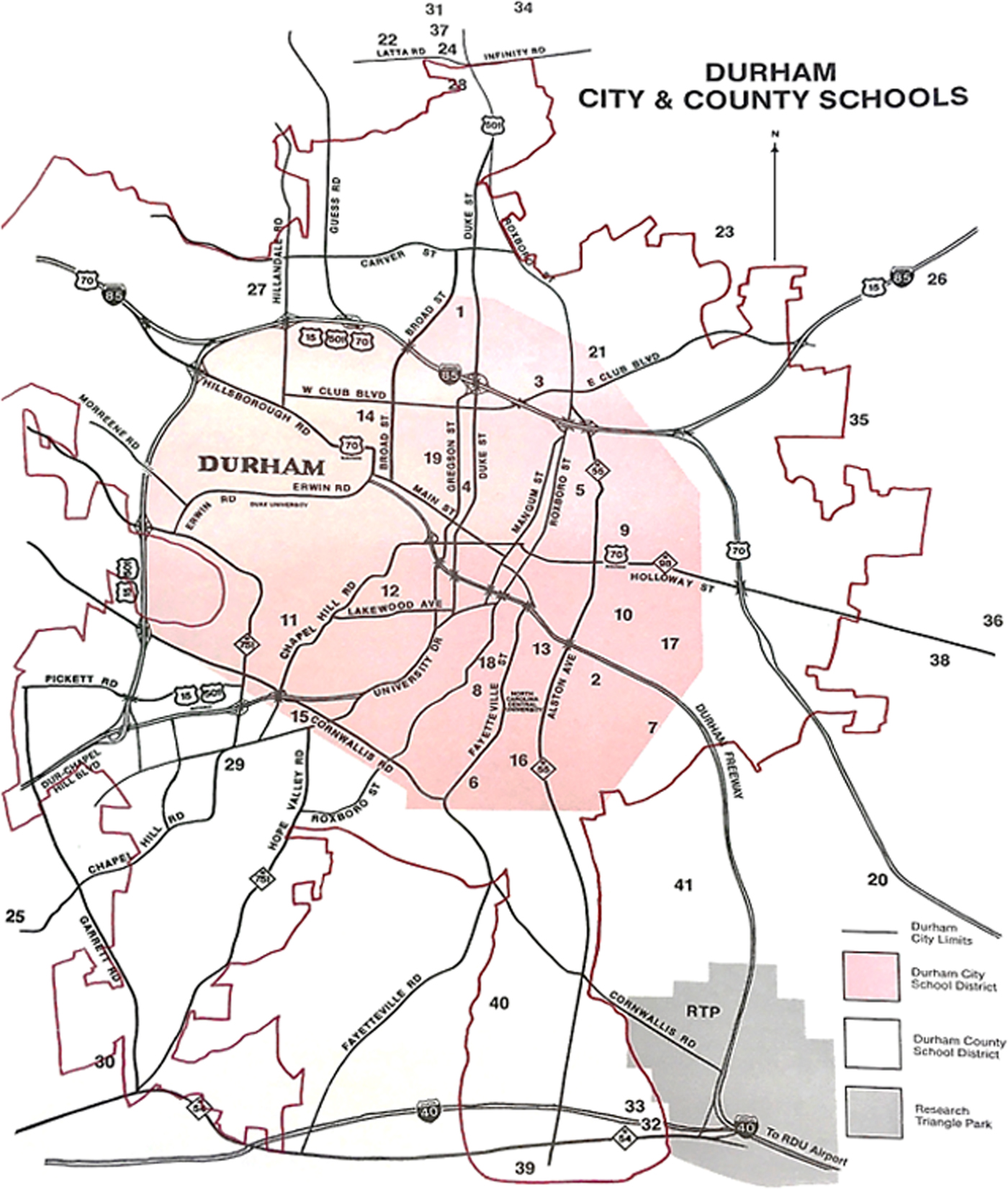

In 1965, only 10 percent of suburban areas annexed by the city voted to join the city school district. As a result of continued expansion, in 1971, only 46 percent of the Durham city area was operated by the city school district. This went on for years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. City and County School Districts, 1988–1989. Because of annexation laws and opt-out mechanisms, the city school system only covered the inner core (shaded area) of the city of Durham. The rest was operated by the county system, even within city limits. (“Public Education: Durham, 1988–1989,” box 75, folder: Durham Board of County Commissioners Merger Plan, Feb. 1992, 9, Durham Public Schools Collection, North Carolina Collection, Durham County Library.)

These “city-out” enclaves presented the most visible expression of segregation along institutional boundaries and highlight the use that white citizens made of existing policies to curtail meaningful desegregation. A 1971 study by a group of attorneys stated: “The ‘city-out’ enclaves preclude racially balanced schools within the city of Durham and establish built-in racial discrimination within the city itself.”Footnote 44 As this example shows, schools did not merely reflect housing segregation, they were segregative forces themselves. These separate pockets only existed for the schools: city-out residents enjoyed city services in terms of utilities and transportation.Footnote 45

The enclaves had deep financial implications. The city schools could not levy taxes for the city-out areas, even as all city residents, including residents of the city-out areas, voted in city school board elections—city-out residents had political power over the city schools but did not contribute to them financially, and their children attended the whiter, wealthier county schools. As the city grew, its schools became increasingly poorer than the county schools, which collected more money from local taxes.Footnote 46 This specific arrangement shows that the fiscal disadvantage of urban schools did not stem from white migration only but from many forms of fiscal policy-making that granted greater choice to white residents regarding the school system to which they wanted to contribute their tax money and send their children. The statutes also gave city-out residents more political weight in school board elections.

In the summer of 1971, a special community relations group called the Save Our Schools (SOS) Durham Charrette addressed the issue of racial integration in Durham.Footnote 47 The two Charrette cochairs embodied Durham's intense racial polarization: Ann Atwater was a local black advocate and C. P. Ellis was the leader of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.Footnote 48 Ann Atwater had been a community activist since the 1960s, when she became a central force in the war on poverty efforts in Durham as part of Operation Breakthrough, a war-on-poverty effort to mobilize poor Durhamites.Footnote 49 At the time, Ellis believed that the Klan was a legitimate actor in local affairs, and he made a habit of attending city council meetings in Durham.Footnote 50 Ellis recalls the Charrette days as a transformative experience in which he realized that black people and poor white people all suffered from the difficulties urban schools faced.Footnote 51 He left the ten-day open Durham Charrette with a completely different understanding of racial inequalities, became a civil rights activist and helped organize integrated unions for Durham workers.

After several days of debate around school integration, including the question of the merger, the Charrette conducted a public opinion survey. Results indicated that Durham residents would favor a merger at the polls.Footnote 52 In November 1971, however, only 4,698 voted in favor of the merger, and 14,710 people opposed it.Footnote 53 Opposition came from the county and city population, from black and white voters, albeit on different grounds. The white population feared busing, an increase in tax rate for the county, and a decrease in educational quality.Footnote 54 Black Durhamites, including Lavonia Allison of the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, denounced a white agenda to seize control of all schools.Footnote 55 Fears of losing job security under a merged system that would potentially discriminate against black teachers and administrators also alarmed black Durhamites.Footnote 56 John Wheeler, leader of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs, also pointed out that the bond proposal would disproportionately benefit county schools for school construction, with the city schools receiving only $5 million out of the $17.5 million that would have resulted from the bond issue.Footnote 57

Figure 2. Ann Atwater, a leading advocate for African Americans in Durham, and C. P. Ellis, a former member of the KKK, were working as co-chairs of the Durham Charrette in 1971. (Jim Thornton, “SOS Charrette,” July 21, 1971, Durham Herald Co. Newspaper Photograph Collection #P0105, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)

The question of political power for different racial groups was a linchpin in the merger debate. In the early 1970s, school board representation was beginning to shift. The city was somewhat unique: contrary to what occurred in many other places, it had not closed its historically black schools as a result of desegregation.Footnote 58 Many black Durhamites advocated against the merger at a time when they were gaining influence on the city school board, which had previously been all white and all male. Josephine Clement became the first black woman on the City Board of Education in 1973, when the Board was still appointed, and she was elected chair in 1978 with the first city elections. In 1975, four out of five members on the Board were black.Footnote 59 Clement fiercely opposed the merger in 1971—she was, in her words, “chauvinistic about the city system.” By 1989, however, she supported the merger, changing her mind because of the stark inequalities between the two districts.Footnote 60 The potential dilution of black control over the city school district was a core theme throughout the merger debates, as the potential merger threatened job security for black teachers and administrators as well as the district voting structure of the school board elections.Footnote 61

After the merger was struck down at the polls in 1971, city school board member Stephen Harward attempted to convince the county and city school boards to bypass the vote and implement the merger anyway, but to no avail.Footnote 62 Others, who were equally convinced of the necessity of a merger to achieve racial balance and to reduce the increasing inequalities between the two systems, turned to the court. The civil rights attorneys who had litigated the local desegregation lawsuit in 1961 on behalf of black students in the Durham city schools filed a new motion against the two school boards on December 18, 1972.Footnote 63 Their case, Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education (1974), alleged that the concentration of the white population in a separate district in the suburbs and in city enclaves was a “new version of segregation.”Footnote 64 Merging was, in the plaintiffs’ view, “the only way to offer stable desegregation and equality of educational opportunity to the residents of the heavily black and poor city school district.”Footnote 65 The judge ruled against the plaintiffs, stating that they had not provided sufficient evidence of the county district's intent to segregate.

The Wheeler decision had consequences that would shape the metropolitan landscape of Durham for decades to come in a way that mirrors federal developments on these issues. In 1973, in San Antonio v. Rodriguez, the Supreme Court justices upheld the school finance system in Texas, despite the irrefutable inequities between wealthy and poor districts to which it led.Footnote 66 In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in Milliken v. Bradley that desegregation remedies could not involve separate school districts—in this case, both urban and suburban districts in Detroit, Michigan—unless plaintiffs showed that both school districts intentionally contributed to segregation in the inner city schools.Footnote 67 Milliken significantly curtailed desegregation across different districts. Law and education scholar James Ryan drew a comparison between school finance and desegregation cases, indicating that both reinforced the boundaries between cities and suburbs and both announced what he argues has been the most powerful paradigm of post-1973 metropolitan education reform: “Save the cities, but spare the suburbs.”Footnote 68

In the middle of these major federal cases, the Wheeler case paralleled the Supreme Court's reasoning. In 1974, the district court stated that segregation in Durham could not be attributed to the actions of city officials, school boards, or official policies, but resulted from a “variety of complex and interrelated social factors which defy tidy cause and effect analysis.”Footnote 69 This description of district lines erases the authority of school districts to alter their assignment plans as well as the mechanisms that allowed city-out areas to choose the white county system regardless of geographical location, and inconsistently when compared to other city services. Milliken, Rodriguez, and Wheeler belong to a long list of court decisions that refused to see the history of school boundaries as a history of intentional segregation and the hoarding of resources.Footnote 70 Yet school district lines, far from being accidental, are constructed boundaries that create channels for isolating tax money and crystallizing power, and that have the effect of limiting opportunities for certain students—disproportionately poor students of color.Footnote 71

Faculty and administrators at Duke University, an elite institution in Durham, were divided after the merger failed at the polls.Footnote 72 Perceiving the degradation of city schools, some faculty members raised serious concerns about the attractiveness of Duke for potential recruits.Footnote 73 In June 1973, Chancellor John O. Blackburn proposed establishing a special private school for faculty children, and his plan for a “demonstration school” received support from Terry Sanford, then President of Duke University.Footnote 74 Several professors spoke in favor of the proposed private school. Sam Gross, a chemistry professor, testified at a university forum that the need for a private school for children of Duke professors was “extremely urgent,” and claimed that his children suffered in Durham public schools because “they [were] excluded from the black society.”Footnote 75 He argued that the University was losing faculty members because of the poor public schools, although others challenged his statement.Footnote 76 The plan sparked a heated debate in Durham, with school board members in the city and county districts condemning Duke's secessionist reaction.Footnote 77 Mrs. Dillard Teer, who sat on the Durham City School Board, warned that the Duke private school would “certainly make the [public] schools poorer.”Footnote 78 Some Duke faculty members also opposed creating a private school, and called it “paternalistic, isolationist, and potentially racist” in the university's newspaper, although they remained anonymous.Footnote 79 Donald Fluke, who had actively promoted the merger in 1971, fiercely opposed Blackburn's plan, which was abandoned as a result of the controversy.Footnote 80

What faculty members at Duke perceived was a sharp decline in the quality of public schools, with mixed arguments about the increasing “minority” population and deteriorating standards, and the murky causal arguments of the debate underline persisting racist assumptions about educational standards with an increased population of students of color. Yet schools were increasingly suffering from reduced funds.

Fiscal policies continued to disadvantage urban schools in Durham, with two separate districts and city-out legislation entrenching the inequities. But advocates for consolidation faced strong political obstacles in the 1970s. As opposed to county commissioners and business groups, neither the county nor the city school boards supported the merger. These political obstacles were greater in Durham than other areas, for example, in Charlotte, where the city and county districts merged through a referendum as early as 1960, under the leadership of civic leaders who were concerned about administrative efficiency, and in Raleigh, where the two districts merged in 1974.Footnote 81 In Charlotte and Raleigh, political interests already closely aligned with business agendas, especially around economic development.Footnote 82

Consolidation: 1988–2001

During the 1980s, Durham city schools were plagued with underfunding, decreasing enrollment, low academic achievement, and school violence.Footnote 83 The gradually declining enrollment in the city schools had a significant impact on school budgets, since about two-thirds of the city budget came from the state on a per capita basis.Footnote 84

The district lines between city and county districts also prevented any meaningful integration of schools.Footnote 85 In 1988, the county schools were 68 percent white, and the city schools were 89 percent students of color.Footnote 86 As in many parts of the country, the city's inner core had high levels of poverty, which, coupled with the structural underfinancing of schools, led to a dire situation and to a growing negative image for the city, which had the characteristics of an urban “ghetto.”Footnote 87 The 1980 census indicates that the county school district had an income level almost twice that of the city district. The city school district poverty level was among the highest in the state, and was three times that of the county.

The reputation of the city schools worsened, and by 1988 they had the highest dropout rate in the state of North Carolina.Footnote 88 Looking back at the situation in the 1980s, William Bell, later Durham's first black mayor, summarized the situation: “The county (schools) were white, well to do. The city was black, reduced lunch.”Footnote 89

The North Carolina legislature pressured districts across the state to consolidate to increase administrative and financial efficiency.Footnote 90 In May 1988, the Board of County Commissioners in Durham formed the Merger Issues Task Force to conduct a study and issue recommendations regarding a potential merger.Footnote 91 The Task Force's goals did not directly address the state legislature's efficiency concerns and instead had more community-specific priorities. Governance was central to the 1988 study: its first stated goal addressed racial imbalance in Durham, not in terms of the racial composition of student bodies in schools but in terms of school board representation.Footnote 92 With a growing sense that black interest groups dominated the city schools, the merger question had been enmeshed in racial tension for years.

The Task Force's second goal tackled taxes, another major issue that had long been an obstacle to the merger.Footnote 93 The suburban district had a much larger tax base than the urban district, a pattern that mirrored many other metropolitan areas in the United States.Footnote 94 The urban district had a higher tax rate, but could not make up for its smaller tax base, and it had additional spending needs, including language and dropout-prevention programs.Footnote 95 The parallel systems relied on an inequitable funding structure that deepened disparities in wealth. In 1986, one cent of tax in the city yielded about seventeen dollars for a city student, while one cent in the county yielded about thirty-one dollars per student.Footnote 96

Awareness of these structural inequities did not translate into public support for change. Because its recommendations stressed the importance of active community participation, the Task Force planned on holding a new merger referendum.Footnote 97 But the Durham population still strongly opposed the merger, which led the county commissioners to avoid a popular vote and instead enforce the merger through the legislature.Footnote 98 Thus, the planned 1989 referendum never took place. The state legislature had long worked to enable school boards to implement mergers without consulting the public, and it revised and reinforced state statute 115C-67, entitled “merger of units in the same county,” in 1967, 1969, 1981, and 1991 to increase the authority of school boards to implement mergers.Footnote 99

Resistance also came from people who had previously supported the merger. Patricia Neal, a white woman who had actively advocated for consolidation in 1971, and who had been a member of the Durham County Board of Education in 1978, opposed it in 1989 because, in her opinion, racial balance could no longer be achieved, and merging the two districts would negatively impact county schools:

A merger now would mean that you're going to sacrifice the county kids for however many years it takes to straighten out the mess. I think, eventually, it's probably going to come, but it's going to be at the sacrifice of the county kids, and that's difficult because it's going to be chaos, just chaos.Footnote 100

Teachers were also divided on the issue. A 1989 survey revealed that white teachers in the county schools overwhelmingly opposed merging the districts, whereas city teachers—white and black—favored the idea.Footnote 101 Black teachers in the county represented only 15 percent of the teaching force and were split on the question, with 57 percent of them favoring the merger. Differences in pay scale played a big part as the suburban district paid its teacher a higher salary than the urban district.Footnote 102

In the face of strong public resistance, why did the merger occur? The fact that the legislature pressured county commissioners across the state to merge city and county districts does not by itself explain the move, since the legislature's position in that regard had been consistent since the 1970s.Footnote 103 The passing and implementation of the merger cannot be understood when divorced from the urban development context of the late 1980s and early 1990s. At a time when Raleigh was a more attractive city in the Research Triangle area, Durham lagged behind because of its bad reputation.Footnote 104 Business leaders, like university faculty in the early 1970s, knew that Durham's negative image harmed their recruitment efforts. A couple of decades later, County Commissioner Bell made downtown revitalization his task, with schools playing a crucial part in that project.Footnote 105 As an IBM engineer, he was familiar with corporate interests, and his strong ties to the business community helped him attract major technology companies to the area.Footnote 106

In 1965, IBM was among the first big names to settle in the region.Footnote 107 It validated the entire “industry hunting” project of the RTP, which relied on special tax advantages in the 1960s.Footnote 108 In a 1999 interview, Lauch Faircloth, a US senator and businessman who had worked for the North Carolina Department of Commerce to develop the RTP in the 1970s and 1980s, described how the RTP leadership gradually targeted high-tech industry:

We really concentrated on the high tech, micro-electronics industry. You can't do everything. There was some heavy industry and the expansion of our textile industry. We tried to work very closely with the new, modern, sophisticated textile industry, but the pharmaceuticals and that type of industry, we worked real hard on [those industries].Footnote 109

These companies relied on highly skilled employees, with IBM involved in literacy programs and dropout prevention in the region since the 1980s. In 1988, an IBM representative stated, “We believe if we as a nation are going to survive and IBM is going to survive as a corporation, we have a responsibility to help the educator.”Footnote 110

Bell's rationale for revitalizing downtown Durham was to attract new employees so that the city too could reap the economic benefits of the booming RTP as well as attract new businesses with a well-educated potential workforce coming out of the city schools.Footnote 111 Large companies that settled in the RTP area generated significant revenues through taxes, either for Raleigh or Durham County, depending on their location in the RTP. Clement, chair of the City Board of Education during the 1970s and later a county commissioner, drew direct connections between the locations of businesses outside the city, which she identified as the direct result of urban planning starting in the 1950s, and low city school budgets:

The city has a very small—the city school district, I should say—has a very small tax base as opposed to the county school system. … It is particularly true here in Durham County because of the Research Triangle Park. Also, because we had a very severe urban renewal program which tore down homes and businesses and what not, and hastened the flight to the suburbs so that the shopping centers and so forth are outside the city. By not moving the city district lines to keep up with the city governmental lines—they are not coterminous—we don't even get the advantage of the shopping centers and businesses like that, that are all on the outskirts of town.Footnote 112

Compared to the Durham city district, the Durham county district benefited tremendously from the arrival of “taxpaying giants.”Footnote 113

Comparing the fates of Raleigh and Durham further illuminates the crucial role that schools played in the economic development of the two neighboring cities. Both cities held referenda on mergers in the early 1970s and, in a striking parallel, they were both defeated by a three-to-one margin. But in 1974, the Raleigh leadership passed the merger through the legislature anyway, much like the Durham Board of County Commissioners resorted to in the 1990s.Footnote 114 In Raleigh, this was due to local elites with vested interests in sustaining vitality in the downtown area, causing them to bypass the nonbinding popular vote. Historian Karen Benjamin describes the actions of the Raleigh “elite” as part of an effort to “save” downtown Raleigh by eliminating incentives for white outmigration to the suburbs. Contrary to Durham, where opposition had come from both the city and county districts, opposition to a merger in Raleigh largely came from white suburbanites. Business leaders feared that “a blacker, poorer city district surrounded by a whiter, wealthier county district would further damage the economic vitality of downtown.”Footnote 115 In a fascinating mirror image with Durham, where the referendum vote dictated the actions of the school boards, Raleigh schools actually desegregated at the metropolitan scale, with two-way busing between city and suburbs as a result of the merger.

The state capital disproportionately profited from the economic dynamism of the RTP. Frank Daniels Jr., publisher of the News & Observer in Raleigh, compared the two cities: “We prospered more than Durham, because school merger helped prevent Raleigh from looking like a doughnut, with a poor, black pocket in the middle.”Footnote 116 Real estate developers favored Raleigh, citing the divisive debates in Durham as deterrent: “Durham's contentious, feuding city and suburban school districts were sharply divided by race and class. They were not as attractive to real-estate developers and young, upscale families as the consolidated, integrated school system that Raleigh built in the mid-1970s.”Footnote 117 The comparison highlights how central schools were in shaping the economy of the two neighboring cities.

The stories of Durham and Raleigh thus point to alternative paradigms that developed during the period. “Save the cities, but spare the suburbs” seemed to dominate legal developments in the 1970s, but private actors and urban developers in the region suggest that private forces sometimes framed “saving the city” as a way to boost the economy in a broader context of new economic trends and Cold War competition, even if it meant involving the suburbs.Footnote 118 Just as the RTP symbolizes private and public sector partnership, converging interests between corporate entities and city officials, sometimes embodied by a single individual such as Bell, shaped education policy in the region.Footnote 119

Yet even with new political leadership aligned with business interests, it is not certain that the two districts in Durham would have merged without a simultaneous change in legislation. Until late 1991, county commissioners in North Carolina did not have the authority to merge two school districts without consent from both school boards, and the merger divided Durham residents, especially because of what it meant for political power.Footnote 120 The question of school board representation had always been one of the most divisive issues in the merger debate.Footnote 121 In 1996, a reporter summarized the rationale of county and city residents, who claimed governance on their districts: “Suburbanites wanted no part in solving these problems. Durham's black leaders, who dominated school politics, didn't want a merger either. Maybe their system was bad, they reasoned, but at least it was theirs.”Footnote 122

Many Durham residents wrote to the North Carolina Superintendent of Public Instruction Bob Etheridge to express their frustration, and their letters capture intense racial divisions. Dan Hill, a white citizen, resented what he perceived to be a “trap” devised by Bell and the legislature to favor black Durhamites: “William V. Bell, Chairman of the Durham County Commissioners recognized a window of opportunity to impose merger upon the Durham voters based on a structure that is favorable to him and the black community.”Footnote 123 Bell had been elected to the Board of County Commissioners before the merger law had changed, at a moment when he would not have had the authority to merge the districts without approval of both school district boards.

Some specifically worried about school board elections under a merged system in Durham. Black school board members had historically been elected through district votes. At-large elections would lead to greater white representation, because the entire Durham county population was whiter, even though the school population had a higher percentage of black students. Harris C. Johnson, a black teacher in the city system who led the grassroots American Voter Education Registration Project in Durham, argued:

The Seven Single Member Districts is the only viable plan which will insure equity for all citizens. As a former candidate for the Durham County School Board I am quite aware of how difficult it is for a minority candidate to be elected with the present at-large method for electing School Board members.Footnote 124

Conversely, Charles J. Stewart, the president of Guaranty State Bank in Durham, argued that the business community wanted a mix of district and at-large elections: “Merger of Durham's schools is needed, but not at the expense of racial polarization for the foreseeable future, a factionalized board with all members representing specific districts only, and a dearth of support from citizens who feel forcefully disenfranchised.”Footnote 125

Residents brought two different lawsuits in an effort to stop the merger's implementation—both cases hinged on voting rights. Plaintiffs in one case alleged gerrymandering in school board representation, arguing that the new board election system was “set up in a fashion that dilutes the white vote.”Footnote 126 Three white residents argued that the plan for electing members in the new board, which had three members elected from black districts, three from white districts, and one at-large, underrepresented the white population, which was 61 percent overall in the entire Durham area—not noting that the school population was predominantly black.Footnote 127 In March 1996, the commissioners replaced the plan with at-large elections for the seven members, which, as many understood, weakened the influence of black voters who, since the 1970s, historically had controlled district votes.Footnote 128 Equalizing fiscal resources between the city and county districts not only came at the price of black political control but of proportionate demographic representation on the school board.

Seven parents and a student filed a simultaneous lawsuit to challenge student assignment plans.Footnote 129 The parents were white suburban residents who refused transfers to the city schools. Claiming that the urban, predominantly black student population was best served by black leaders, in black-controlled institutions, an African American senior at Hillside High School was among the plaintiffs, which again captures the merger's racial, political stakes.Footnote 130 Plaintiffs dropped their complaints later in 1995, citing procedural issues.Footnote 131

By the end of 1996, after failed attempts to stop the merger, it seemed that the Durham population had become committed to the new consolidated district, and candidates who had been against the merger lost at the school board election.Footnote 132 Durhamites remained divided on questions of representation and student assignment, and many expressed concerns over the educational consequences for the schools. After years of money and energy spent on structurally altering the districts, the educational situation showed little progress.Footnote 133

In the early 2000s, school board representation remained a sensitive topic in the Durham Public Schools consolidated system, whose school board was predominantly white in a district whose student population was 58 percent African American.Footnote 134 Merging the districts allowed for a more equitable funding formula, however, with both tax bases connected and resources flowing more equitably according to student need.Footnote 135 Old local divisions around funding seemed to fade in the decades following the merger. In 2001, the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People led a campaign to oppose a bond proposal to increase funding for schools, arguing that the additional funds would only benefit the building of schools outside of the city. Even though a clear racial demographical separation remained, it was harder to argue that a bond increase would disproportionately benefit white families within a consolidated district. Voters overwhelmingly passed the bond referendum.Footnote 136

Conclusion

Understanding the history of late-twentieth-century metropolitan education has a bearing in analyzing issues that continue to challenge urban education. In 2001, a commission sponsored by the Durham Public Education Network studied the achievement gap in Durham, mainly the discrepancy between the test scores of white children and students of color: 90 percent of white and Asian students performed at or above grade level in reading and math, compared to 60 percent of African American students.Footnote 137 The Network's report included the following statement in bold, capital letters: “The achievement gap is no one's fault, but it's everyone's responsibility!”Footnote 138 This sentence suggests that the achievement gap has no history, yet historians have long worked against this notion. The phrase fails to convey how stakeholders with specific motivations for racial and fiscal isolation had maintained and drawn lines that would promote particular agendas. These divisions created exclusionary, centrifugal hubs of resources that contributed to reinforcing the difficulties of the inner city schools.Footnote 139 Erasing this history runs the risk of attributing differences in achievement to essential characteristics.Footnote 140

The black population in Durham faced a difficult compromise between equalizing resources and retaining political power over the city schools. Thus the difficulties urban schools in Durham faced are not solely ascribable to “white flight” and desegregation policies.Footnote 141 These sacrifices stemmed from persistent racist financial policy and administrative choices, such as “city-out” legislation, that had advantaged white suburbanites since the 1950s, and beyond.

Although the 1991 merger worked to erase entrenched boundaries between city and county schools, it failed to unravel them completely. Moreover, starting in the 1990s, many affluent families opted out of the traditional public school system and instead chose private academies and charter schools.Footnote 142 Even within the new Durham Public Schools system, discrepancies still exist between affluent and poor areas. One outraged blogger in 2008 asked, “Why in hell do we tolerate a world in which there are schools with 70% and 90% free and reduced lunch rates? Why do we tolerate an educational system that segments out schools … to be warrens of the poor alone?”Footnote 143 The merger failed to undermine the concentration of poverty in city schools, and did not end racial segregation. In 2001, Rogers-Herr Middle School, located in the city's southwest, was 74 percent black, 10 percent Latinx, and 16 percent white.Footnote 144 In 2018, its population was 59.8 percent black and 16.2 percent Latinx.Footnote 145 Rogers-Herr is located just two thousand feet from the private Durham Academy Middle School, which in 2018 was 73.6 percent white.Footnote 146

In an educational landscape increasingly fragmented by the advent of school choice, school district boundaries are still very much a live political and legal issue. In 2017, Republican members of the North Carolina legislature introduced a bill aimed at splitting consolidated districts into smaller units.Footnote 147 Law professor Derek Black, who has written extensively on the inequitable effects of economically isolated school districts, denounced these state efforts to dismantle “the lynchpin of equality and integration—the county wide school system structure,” and to create “a thousand isolated pockets.”Footnote 148 Dismantling countywide systems would lead places like Durham to reverse consolidation and thereby encourage racial and economic separation, not only between the city and its surrounding suburbs but perhaps even smaller units of racially, socioeconomically, and financially isolated school districts.Footnote 149