Javakheti is an historical region located in the southern part of the country of Georgia. It is situated between the Mtkvari River to the west, the Javakheti and Trialeti mountain range to the east and north, and, in certain periods, it spread to the south, reaching the sources of the Mtkvari River. At present, Javakheti is part of the Samtskhe-Javakheti administrative unit (Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda municipalities).

Based on Urartian written sources, some researchers identify Javakheti as the historical country of Zabaḫae, which was located at the sources of the Mtkvari River (Melikishvili Reference Melikishvili1960: 446). The Javakheti Plateau contains a series of prehistoric fortresses known as cyclopean complexes—structures built with dry-masonry (Figure 1)—which are generally dated to between the Late Bronze Age and the end of the Iron Age (G. Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili and Kipiani2012: 139). These form part of a wider phenomenon of cyclopean complexes spread throughout the territories of modern Georgia, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran. This article discusses the results of an archaeological survey conducted in the historical Javakheti region in 2017. The aim of the project was to record the Late Bronze–Iron Age fortress complexes.

Figure 1. Cyclopean structure in the village of Aspara (photograph by D. Narimanishvili).

Scientific research on megalithic sites in Georgia has been ongoing for more than 130 years. The importance of these sites was discussed at the fifth Archaeological Meeting, held in Tbilisi in 1881. Cyclopean fortresses have long been at the centre of the study of Late Bronze–Early Iron Age history, architecture and constructive art in the South Caucasus. Recent research has begun to link South Caucasian cyclopean complexes to early state formations (Daiaeni/Diaukhi) including those (Zabaḫae, Tariuni and the like) mentioned in Assyrian and Urartian written sources (G. Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili and Kipiani2012: 141; D. Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili and Shanshashvili2016: 213; Narimanishvili et al. Reference Narimanishvili, Vadachkoria, Tamazashvili, Juszczyk and Tomczyk2017: 129–30). Written sources from the neighbouring empire of Urartu specifically mention fortified complexes, as well as providing information about the social structure and economy of the small states in the region.

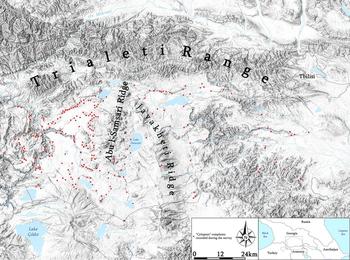

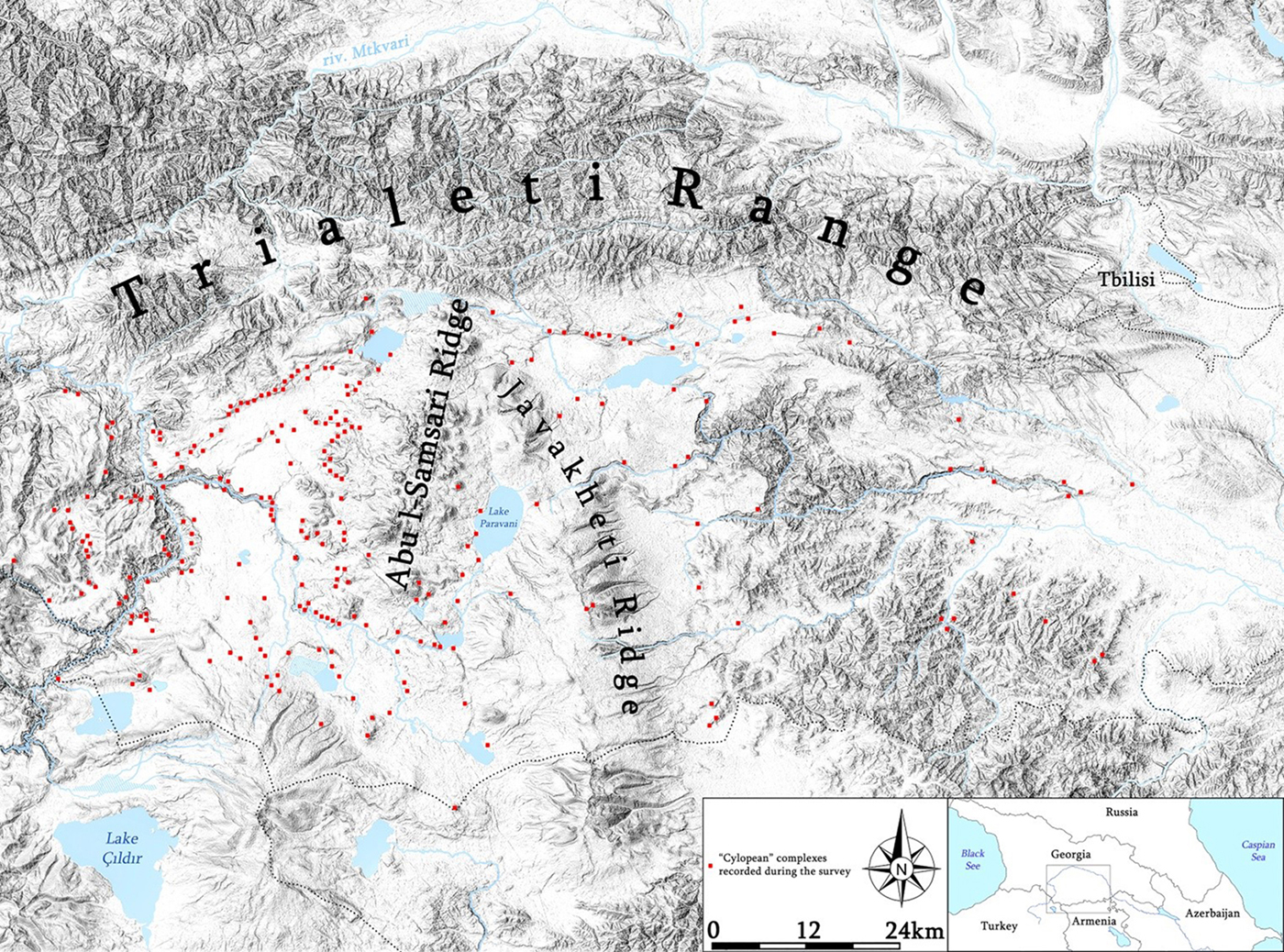

The project aims included producing a complete list of all known fortresses and recording each one in the field. Before fieldwork, I undertook a thorough literature review, as well as using Soviet-era and more recent (Google Earth, Zoom Earth and Bing Aerial) aerial photographs as a form of desk-based assessment. All possible sites were visited, described and photographed, and their coordinates were recorded; this enabled the creation of a database. This research shows that the greatest concentration of cyclopean complexes in southern Georgia is found on the Javakheti Plateau, where 162 complexes were documented, of which 84 were previously unknown (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spread of cyclopean complexes in southern Georgia (map by D. Narimanishvili).

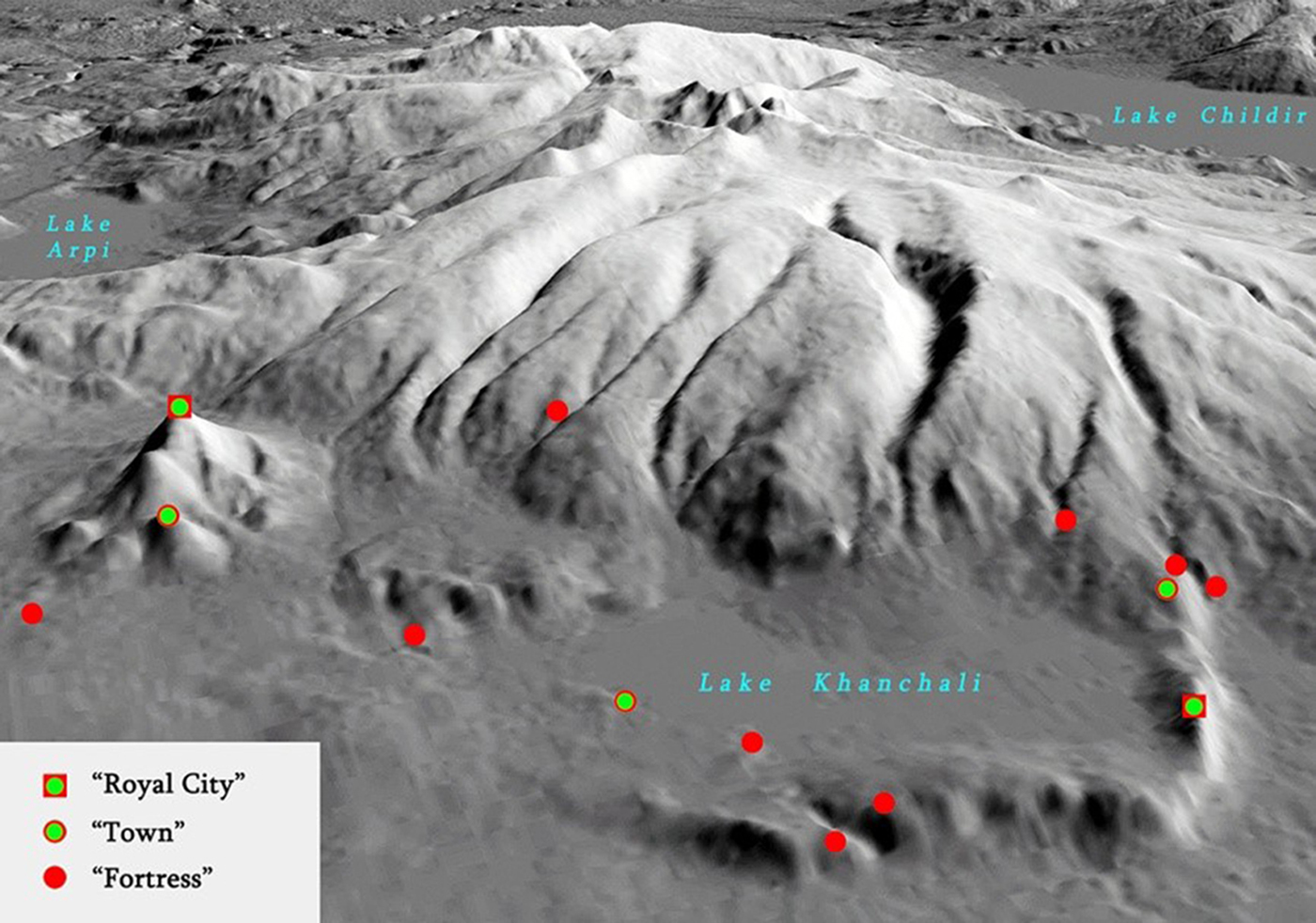

Urartian and Assyrian written sources give information about the structure of the cyclopean complexes in the South Caucasus. Sources suggest that three kinds of fortified complexes coexisted within the territory of Diaukhi and its surrounding polities: ‘Royal cities’, ‘towns’ and ‘fortresses’ (e.g. Melikishvili Reference Melikishvili1954: 215).‘Royal cities’ were apparently administrative centres, which were well protected, evidenced by the fact that the well-furnished Urartian army struggled to conquer them. It seems from Urartian written sources that the small settlements surrounding the royal cities were referred to as towns.

As part of the project, I attempted to fit the cyclopean fortresses into the categories described in the Urartian written sources. Large settlements (0.8–10ha in size) in the region with complicated fortification systems, including complexes of large walls and dry moats, often constructed on prominent, difficult-to-reach mountaintops (Figures 3–4), were identified as ‘royal cities’. The settlements around these cities are located in less prominent positions (Figure 5) and are protected by a wall and a dry moat, and are referred to as ‘towns’. A ‘fortress’ can be identified as a complex that is established in a strategic place, often at points of control in the landscape where routes may have met. In some cases, all three types of complexes are located in close proximity to each other, sometimes making use of the natural landscape to create a single fortification system—a ‘local region’ (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Plan of the cyclopean complex of Abuli (G. Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili and Kipiani2012: 188).

Figure 4. Citadel of the cyclopean complex of Abuli (photograph by D. Narimanishvili).

Figure 5. Fortified settlement near Baraleti Village (photograph by D. Narimanishvili).

Figure 6. Concentration of cyclopean structures around Lake Khanchali (image by D. Narimanishvili).

At the end of the fourteenth century BC, the political and economic situation in the South Caucasus and Anatolia changed radically, due in part to the fall of the Mitanni Empire. The trade network, which supplied north Mesopotamia and the Levant with different raw materials, collapsed and the Assyrian and later Urartian empires expanded (Shanshashvili & Narimanishvili Reference Shanshashvili, Narimanishvili, Menhert, Menhert and Reinhold2012: 178–79). To the north, Assyria and Urartu were bordered by more fluid political configurations in the highlands of Eastern Anatolia and the South Caucasus—areas rich in metal. A list of tributes charged to the South Caucasian ‘countries’ by the Assyrian and Urartian kings shows that metals were supplied, along with other resources.

The expansionist tendencies of both the Assyrian and Urartian empires brought them into conflict with the groups occupying the South Caucasus. The aims of the imperial powers were to control the metallurgical centres and trade routes, as well as to extract tribute (Bongard-Levin Reference Bongard-Levin1988: 103 & 108). This was probably the impetus for local tribes to unite in the struggle against these enemies (Melikishvili Reference Melikishvili1954: 251–55). The resistance of the population of the South Caucasus to empirical expansion from the south is reflected in the intense construction of protective fortification systems.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation (#YS-2016-67, Megalithic Fortification Systems in Georgia).