Writing in the International Journal of Comic Art, Dartmouth professor Michael A. Chaney opens a recent essay on the first book of John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell's best-selling three-part graphic memoir March with reflections on his students’ reaction to its depiction of the American civil rights movement:Footnote 1

Monumental though Lewis and his text may have been … neither he nor his memoir could satisfactorily rebuke the injustices associated with what seemed … a daily report of chilling police shootings. Many demoralized students wanted a graphic text with more bite … They wanted a text in aggressive proportion to the fatal onslaught of state-sanctioned brutalities perpetrated against innocent, often poor black subjects. Contrary to the unsteady consensus of the moment, March was perceived to be eking out a message of ultimate trust in the state and state processes … [S]everal of my students found March's narrative framing of political optimism staggeringly inappropriate to the Uzi spray of racism from media outlets. Beyond harboring an agenda of black political conformity, March smacked of chauvinisms both political and otherwise, tying the graphic memoir to a type of black resistance widely thought to be ineffectual in our contemporary moment.Footnote 2

Gauging the students’ reaction as dissatisfaction with “the text's political failings and historical fetishes,”Footnote 3 Chaney recognizes a yearning for more confrontational narratives and more aggressive political options than offered by Lewis's philosophy of “good trouble,”Footnote 4 the dignified forms of nonviolent protest that defined much of the civil rights movement. At a time when the killings of black Americans by US police dominated the news and when the Black Lives Matter movement was gaining traction, March celebrated nonviolent forms of resistance, expressed a continuing belief in the American political system, and turned to the lessons of the past instead of addressing the problems of the present.

When the first book of the trilogy appeared in 2013, however, Barack Obama was still President and Michael Brown, Miriam Carey, Eric Garner, Mya Hall, John Crawford, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray were still alive. There had been a racially motivated backlash against Obama from the very beginning of his presidency, and police killings of African Americans did not just start in the 2010s. Nonetheless, black civil rights legend and US Congressman John Lewis, his aide Andrew Aydin, and graphic artist Nate Powell found sufficient inspiration in Obama's election to present Lewis's lifelong struggle against racism and discrimination as the prehistory to, and precondition of, the first black President by suffusing the narrative with images of Obama's first inauguration. Lewis and his collaborators celebrate what the books pitch as the long-term impact of the civil rights movement, especially of the Selma, Alabama campaign, in which Lewis was involved as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In Selma's Bloody Sunday: Protest, Voting Rights, and the Struggle for Racial Equality, Robert A. Pratt affirms that the “election of the first African-American president in 2008 reflected the apex of black political power,” which supports March's presentation of the civil rights movement as an eventual success story. Yet Pratt also sees a paradox according to which Obama's election “revealed … an increase in black electoral participation and a rapidly changing political landscape [that] prompted white conservatives to resort to a new campaign of voter restrictions.” His conclusion “that the lessons of Selma have yet to be learned” complicates the historical trajectory of the March books.Footnote 5

Writing more than a decade before Pratt and around the same time Obama prepared his bid for the presidency as a speaker at the Democratic National Convention in 2004, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall had already maintained that rather than unfold along a straight line, the civil rights movement developed from a “dialectic between the movement and the so-called backlash against it.” This backlash “arose in tandem with the civil rights offensive in the aftermath of World War II,” and it did not end in the 1970s, as common movement history alleges, but “culminated under the aegis of the New Right.”Footnote 6 Among the March books’ most prominent political failings may thus be its underestimation of the backlash against the long-term advancements of the civil rights movement, a backlash that had gathered steam during Obama's “eight years in power,”Footnote 7 broke out into the open with election of Donald J. Trump, and undermines the progressive optimism of the trilogy.

Scholarship on March has only begun to account for its political thrust. Those who have engaged with this graphic narrative have noted its entrenchment in what Hall defines as the “dominant” or “master” narrative of the movement, the “confining of the civil rights struggle to the South, to bowdlerized heroes, to a single halcyon decade, and to limited, noneconomic objectives.”Footnote 8 Yet scholars like Michael A. Chaney, Joanna Davis-McElligatt, Markus Oppolzer, Jorge J. Santos Jr., and Johannes Schmid have shown that we should not discard the powerful lessons the March books can teach us about this pivotal period in US history and its contested memorialization. True, the trilogy may sit uneasily with some readers because of its preoccupation with the past and its advocacy of nonviolent resistance. Granted, advertising it as a “roadmap for another generation,” as Lewis did on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, and dedicating it to “the past and future children of the movement” (the three books’ identical dedication) may strike others as overly didactic. And yes, the focus on the “classical” phase of the movement – bracketed by the US Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954 and the civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s – and its relative neglect of “the interweavings of gender, class, and race” raise difficult question about March's historical conservatism.Footnote 9

Despite these caveats, the March books deserve critical scrutiny as they join other graphic memoirs of the movement – such as Ho Che Anderson's King (1993–2002); Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell's The Silence of Our Friends (2012); and Lila Quintero Weaver's Darkroom (2012) – in transposing movement history into graphic form.Footnote 10 They reiterate but also complicate the master narrative, not so much by extending what Martin and Sullivan criticize as “a limited, all-too-familiar repertoire of events, places, and people,”Footnote 11 but by negotiating the many layers of mediation and remediation that constitute what we have come to understand as the civil rights movement: by remediating what Leigh Raiford in her work on civil rights photography calls the “media-mediated events” that shape our sense of the movement.Footnote 12 Using the tools of graphic storytelling, the March books alert us to the highly mediated “process by which history is told and retold, produced and reproduced, and narrativized and renarrativized before becoming enshrined in our memories and disseminated for sociopolitical purposes.”Footnote 13 They enact “a metacritical awareness of history as an editorial and curative process” by constructing an account of the movement that also serves as a critical engagement with its initial mediation, particularly through photographs and television footage, and as a retroactive memorialization through graphic remediation.Footnote 14 Moreover, they elicit a “metacritical pedagogy” that empowers them as didactic tools for investigating representations of American history,Footnote 15 the workings of social protest movements, and the moral questions that continue to haunt us in the present.

In the following, I distinguish between the didactic impulses of the books and their usefulness as a didactic resource in current pedagogical settings. I begin with a look at the books’ didactic impulses. As suggested by the title of Hasan Kwame Jeffries's Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement (2019), it is crucial to understand how they excite, engage, educate, encourage, enable, empower, and enlist their readers before we think more specifically about how to implement their lessons in the classroom.Footnote 16

DIDACTIC IMPULSES

The March books tell the life story of US Congressman John Lewis from his childhood in poor rural Alabama to his seminal role in the black freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s. As a former president of SNCC and the only still living member of the “big six,” Lewis is at once an eyewitness to some of the movement's most important moments and a historical figure whose legacy the graphic memoir celebrates.Footnote 17 We can identify his triple role as participant, politician, and autobiographer as a prerequisite for the narrative since Lewis's life is inextricably connected with the national past and because the retelling of this past is both a personal and a political project. March: Book One visualizes this connection in an image of present-day Lewis with a visitor and her children in his office in Washington, DC.Footnote 18 He is gesturing toward a wall filled with photographs as he is about to tell a story about his childhood. Lewis is used to narrating such stories, it seems, and he has already assembled a comic-book-like version of his life – a sequence of framed images – on that wall.Footnote 19 Instead of pretending to offer a strictly factual account of the movement, the scene introduces a sense of self-awareness about its status as a graphic narrative that remediates an already multiply mediated biography. This narrative self-consciously emerges from the Congressman's personal experiences and convictions, but it pursues a broader agenda, offering lessons about the civil rights struggle especially for the younger generation.

The scene in Lewis's office also teaches us a lesson about genre. As a graphic memoir, March belongs to the realm of creative nonfiction and differs from scholarly studies of the civil rights movement, in terms of both how it narrates the story and the evidence it enlists. This generic middle ground – personal recollection, historical accounting, creative depiction – opens up a productive line of inquiry into the very nature of constructing autobiographically inflected history in graphic narrative. This is crucial because both scholarly accounts and graphic nonfiction rely on the same image archive, especially photographs and television footage that “have shaped and informed the ways scholars, politicians, artists, and everyday people recount, remember, and memorialize the 1960s freedom struggle.”Footnote 20 That we are perusing a collaborative work by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and graphic artist Nate Powell complicates notions of autobiographical authenticity and direct access to personal memory. It is Powell's visuals that set the tone of the narrative, rendered by an artist who was born after the heyday of the movement and who, like Andrew Aydin, cannot draw on his own memories to craft the story.

A scene in March: Book Two addresses this complex intermixture of recounting, remembering, and memorializing the movement. The year is 1962, and John Lewis, as field secretary of SNCC, is leading a protest against a racially segregated public pool in Cairo, Illinois. Presenting a subjective account of this event might have granted Lewis special narrative authority and political credibility as an eyewitness, but the depiction foregrounds the fact that historical access to the event depends on multiple layers of mediation and remediation. A small inset panel on the left shows SNCC photographer Danny Lyon, a white Jewish New Yorker who covered the protest for SNCC's Photo Agency, founded to retain maximum control over the documentation and presentation of the group's activities and deliver raw material for media campaigns.Footnote 21 Lyon took a photograph that would became “probably the most popular poster of the movement” when,Footnote 22 in 1963, SNCC cropped the image, added the slogan “Come Let Us Build a World Together,” and sold 10,000 copies of it.Footnote 23 Powell remediates the image on the same page (Figure 1).

Figure 1. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

The visual depiction of this photograph in March differs from the rest of the page, indicating a chain of mediations and remediations from photographic image to poster to graphic memoir. This chain precludes any clear distinction between historical event, its initial photographic mediation, and its later narrativization for various political purposes.Footnote 24 It motivates a look into the many media representations of the movement, turning readers into active sense makers by prodding them to grasp the nature and scope of the movement's visual archive. This includes SNCC's practice of hiring “field workers with cameras” like Lyon, whose photographic records were not only widely circulated but also repeatedly reframed by different institutions, from SNCC's “propaganda machine” to newspapers like the New York Times and the Washington Post.Footnote 25

As active sense makers, attentive readers will discern a discrepancy between the original photograph and the poster, both of which March evokes. Whereas the poster centers on three kneeling figures – a girl flanked by two young men, the one to the viewer's left being John Lewis – the photograph shows another girl to Lewis's right. Transforming Lyon's photograph into the poster, Lyon or someone at SNCC cropped the image and erased this other, thirteen-year-old, girl from the visual narrative, literally placing her outside the political frame.Footnote 26 But March rehabilitates her as a central figure of the protest by providing a fuller sequence, and not just an isolated image, of events already recalled in Walking with the Wind, as they visualize “what happened just after that photo was taken.”Footnote 27 The medium of graphic narrative is especially suited to such visualization, as panels sequentially arrest specific moments of an ongoing action. In the extended scene in March, we see a pickup truck racing toward the courageous girl whom SNCC had erased from the poster. She is standing in the street, steadfastly facing the approaching vehicle as others are scooting away from its dangerous path. The truck suddenly stops, then speeds away, leaving the injured girl behind.

This sequence represents a complex co-presence of personal memory, recorded history, and creative memorialization. Recorded by Lyon's camera in 1962, remediated in the following year through the SNCC poster, recalled in prose memoirs by Lewis and Lyon (the latter of which ironically reprints the poster but not the original photographFootnote 28) in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and then re-remediated through Powell's drawings, the Cairo protest has obviously been widely visualized. But as the scene in March alleges, photograph and poster only provide a glimpse of the event; they are only snapshots whose iconic power stems precisely from their status as single images that absent more than they present (even though Lyon took other, less well-known photographs that day). Moreover, it is impossible to gauge to what extent Powell's representation is based on the photograph, the poster, or Lyon's and Lewis's memories of the moment. This complicates Lewis's status as an autobiographer as personal memories of the past intersect with proliferating media images and narrative accounts. As we can learn from this depiction, while March may be complicit in the master narrative of the movement, it also reveals its reliance on different forms of mediation and remediation, venturing beyond dominant images and including protest that took place outside the South.Footnote 29

March, moreover, is “a memoir that also serves as a recruitment tool for political activism” rather than merely an attempt at graphically documenting American history.Footnote 30 We must therefore situate the trilogy vis-à-vis a vast archive of verbal, visual, and audiovisual treatments of the movement, where emancipatory narratives struggle against a long history of racist caricature to challenge the “historical archive of racist visualization.”Footnote 31 In this context, the photograph at the end of all three March books that shows Lewis with his arms around the white Aydin and Powell as they are standing on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, the scene of the pivotal showdown between the black protesters and the state troopers in 1965, is simultaneously provocative and reconciliatory. By presenting the long-term effect of this showdown as a “friendship [that] is not only interracial but also cross-generational,”Footnote 32 the photograph strikes a note of reconciliation and dreams up a racially inclusive America, dismissing opposing notions of divisiveness and racialized hatred. It superimposes an image of harmonious collaboration over the violence and suffering that are so vividly captured throughout the civil rights archive.

These tensions also shape the graphic memoir's didactic impulses. Speaking to Sarah Jaffe, Aydin named “inspiring young people to get involved and also teaching them the tactics” as a central aim.Footnote 33 In another interview, he claimed, “Our goal was to use this to teach and inspire another generation.”Footnote 34 The cross-generational framing of the narrative and the urge to teach the lessons of the past – especially nonviolent resistance against state-sanctioned discrimination – suffuse the paratextual packaging of the three volumes, bringing us closer to the narrative without yet immersing us in it. Gérard Genette defines paratext as everything that is materially adjacent to but not directly part of the narrative proper – book titles, cover illustrations, epigraphs, introductions and afterwords, footnotes – and understands it as “a zone not only of transition but also of transaction” between the text and the outside world, between author and reader.Footnote 35 The March books invite us into this zone with a profusion of paratextual matter, choosing first and foremost a title that wavers between historical event, movement tactic, moral imperative, and temporal reference. The title evokes forms of mass protest like the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963), where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech,Footnote 36 and where Lewis voiced his indictment of American racism, as well as the March to Selma over the Edmund Pettus Bridge (1965), which serves as the climax of the trilogy. It also captures the ethics of nonviolent resistance: marching through segregated areas without fighting back against white aggressors, meeting racist hatred with Christian love. As an imperative, it calls on young Americans to embrace marching as an appropriate means of voicing dissent, compelling them to battle injustice through peaceful activism. Finally, the confrontation between the protesters and the Alabama state troopers that came to be known as Bloody Sunday took place in March, adding temporal depth to the title's associative web of meanings.Footnote 37

The trilogy paratextually presents Lewis's life story as a paean to an exceptionally American type of heroism that rewards a nonviolent marcher with a political career and a black President. To justify this trajectory, March evokes the rags-to-riches story and its African American variant, the story of racial uplift in the tradition of Booker T. Washington. The inside flap of Book One features a photograph of Lewis and a biographical sketch that identifies him as an “American icon.” His “commitment to justice and nonviolence,” the sketch alleges, “has taken him from an Alabama sharecropper's farm to the halls of Congress, from a segregated schoolroom to the 1963 March on Washington, and from receiving beatings from state troopers to receiving the Medal of Freedom from the first African-American president.” Lewis may have started small by honing his preaching skills before the chickens on the family farm, but he becomes a civil rights leader whose speech at the March on Washington receives extensive narrative space. He is invited to witnesses the signing of the Voting Rights Act by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 and embraces Obama at the beginning of the inauguration ceremony.Footnote 38 This uplift narrative locates Lewis's “personal, political, and moral success … within the democratic institutions of the United States.”Footnote 39 Calling Lewis's resistance “revolutionary nonviolence” and suggesting that the “principles and tactics” developed by the movement “remain vitally relevant in the modern age,” the sketch tries to have it both ways by characterizing Lewis as a revolutionary and a member of the political establishment. Yet what can, with some legitimacy, be debunked as an overly optimistic narrative that downplays the problems of the present and silences more aggressive efforts to fight for justice (such as the Black Panther Party) can also be read as an act of resistance against another master narrative that claims the demise of the movement in the late 1960s and embraces a false “rhetoric of color-blindness.”Footnote 40

The cover images of the three books highlight the tension between the uplift narrative and SNCC's “radical pedagogy” by conjuring up key methods of the movement:Footnote 41 sit-ins, demonstrations, freedom rides, and political speeches.Footnote 42 These methods were widely documented at the time, but instead of simply translating archival material into graphic form, the March books interrogate the very process of historical documentation. Lewis appears in every cover image, first in the center of the boycotters at the lunch counter (Book One), then as a speaker at the March on Washington (Book Two), then as one of the protest leaders on Bloody Sunday (Book Three). While he is clearly presented as the key figure, his graphic avatar does not completely dominate the images. He is usually depicted as part of the movement, appearing as a leader whose effectiveness depended on fellow activists to risk their lives by joining the boycotts, signing up for the rides, attending speeches, and marching. The covers thus support Santos's conclusion that March is “more than the memoir of one great man – it is the biography of a movement.”Footnote 43 They mobilize the same tension between personal success story and political history that informs the subtitle of Lewis's Walking in the Wind: Memoir of the Movement. In fact, if the cover of the first edition of Walking in the Wind focussed singularly on Lewis, playing into the “great-man” approach to history, a later edition (Harcourt Brace, 1999) combined the portrait of Lewis on the top with a photograph of the standoff on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, prefiguring the top-to-bottom structure of the first two March covers. The covers of both the prose autobiography and the March trilogy therefore mobilize the dominant narrative of the movement – the focus on “charismatic personalities (who were usually men) and telegenic confrontations … in which white villains rained down terror on nonviolent demonstrators dressed in their Sunday best”Footnote 44 – while suggesting that there is more to this narrative than meets the eye.

Equally noticeable is the trifurcated mise en page that shapes all three covers even as their architecture shifts from the first two books to the third. The cover of Book One shows the protesters at a lunch counter at the bottom (Figure 2). The title and the names of the authors divide the lower third of the cover from its upper third, which shows people marching with their heads or upper torsos truncated by the upper end of the book. The image in the upper third of the cover evokes a photograph by Charles Moore that shows marchers from the waist down en route to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965.Footnote 45 This is not the first time we encounter marching feet and legs in graphic narratives of the movement. Nate Powell had already chosen this motif in The Silence of Our Friends, and Lila Quintero Weaver uses a very similar depiction in Darkroom, suggesting that these graphic memoirs share a common iconography.Footnote 46

Figure 2. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

Chaney holds that the “arrangement of images and texts [on the cover] … puts th[e] very tension between past and present, words and images, doing and looking on prominent display.”Footnote 47 The only way to come to terms with this tension is to perform repeated acts of closure, which Scott McCloud defines as “observing the parts but perceiving the whole” and as “mentally completing that which is incomplete based on past experience.”Footnote 48 Acts of mental completion induced by the cover of Book One include the need to attach full bodies to the feet of the marchers and connect these bodies with the civil rights demonstrations. They entail processing the possible disjuncture between the reductive assumption that all protesters were African American and the presence of a white boycotter in front of the lunch counter. Enticing an active reception by figuratively reopening the closed lunch counter through a call for closure, the cover challenges readers to consider their own implication in the nation's history of racial segregation. It places viewers behind the counter, on the “white” side of history, while also setting them in opposition to the two white servers, whose bisected faces stare at them from the left and right edges of the image, asking either to be made whole again or to be pushed aside, and thus out of the frame, to create further space for the viewer to gaze at the scene.

The cover of Book Two retains the structural setup of the first cover, portraying Lewis in mid-speech at the bottom as he is facing the Washington Monument and addressing the marchers who had gathered around the reflecting pond on 28 August 1963 as part of the March on Washington (Figure 3). The upper third of the image remediates a photograph of a burning Greyhound bus transporting freedom riders to Alabama, taken near the city of Anniston on Mothers’ Day on 14 May 1961.Footnote 49 In conjunction with the lower third, the cover signals the multipronged tactics of the movement from political speeches to grassroots voter registration, and it announces its increasing intensity, including a violent backlash, as things are literally heating up. This increase, and the rising tension in the overall narrative, are indicated by the middle section of the cover (title, author names), which is tilting slightly upwards to the right. Chaney maintains that “the dual cover imagery of the first two books champions a recovery project that refuses to differentiate between causes and effects” since it is impossible to determine whether the incineration of the bus depicted in the upper section of the cover of Book Two caused Lewis's appearance in Washington or vice versa.Footnote 50 Without a certain telos, different temporalities “collapse … into the paradoxes of revolutionary time”; they embody a “chronotopos of black revolution” that is steeped in the popular iconography of the movement but refuses to be limited by it. Juxtaposed with more recent media images of burning vehicles, such as those of the Ferguson unrest after the killing of Michael Brown on 9 August 2014, they might indeed evoke Amiri Baraka's notion of “nation time,” the “sense that African Americans are no longer outside of history but at its center.”Footnote 51

Figure 3. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

The third and final cover of the trilogy almost abandons the established structure by positioning the black protesters even more clearly at the center of American history (Figure 4). It presents only a single image of the marchers heading toward heavily armed state troopers, and the title/author section points upwards at such a degree as to be almost vertical. Rather than establish a contrast to the first two covers, the image offers a compressed visualization of a critical moment in US history that retains a sense of division even as it seeks to transcend it, suggesting the possibility of progress confronting resistance. In fact, the cover literalizes Genette's definition of the paratext as a zone of transition and transaction by depicting the confrontation between troopers and protesters as a shift in US race relations (transition) while, at the same time, creating an image that admonishes us to turn the recognition of racial injustice into an inspired form of political protest (transaction). Placing television cameramen and press photographers at the sides of the road, the cover introduces a third party into the equation, a party that does not appear on the covers of the first two books but played a significant role in changing public sentiment toward the movement. In this historical moment, race-based segregation – metonymically represented through the trifurcated structure of the covers, with the book title serving as a metaphorical color line – is about to give way to a more inclusive sense of national cohesion. As the marchers are approaching state troopers who have already drawn their weapons, this is a hopeful scene only if we understand its significance as a memory of the movement's longue durée. We already know that the marchers will be brutally beaten and that it will take more action and resolve to gain legal equality through federal legislation, not to speak of the elusive goal of full social and economic justice.

Figure 4. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

Ironically, the image does not bring us closer to the action but chooses a cinematic high-angle viewpoint that takes us away from the confrontation. This perspective transports us from the sense of immediate implication created by cover of Book One and the broadened scope of Book Two to an “ennobled perspective of the voyeur,” foregrounding a “voyeuristic tension that has been anticipated by the presence of the media.”Footnote 52 It changes the focus from the movement to its mediation and memorialization and casts us either as voyeurs, as Chaney suggests, or as metacritical observers aware not only of the movement but also of its initial mediation and ongoing remediation. As voyeurs, we might appreciate Powell's beautiful graphic rendition or find solace in the successes of the movement, from civil rights legislation to the election of the nation's first black President. As metacritical observers, however, we must account for the narrative framing and material packaging of this account. The covers nudge us in this direction through their inclusion of simulated remnants of tape on the books’ spines and what looks like the brittle binding of a library edition or a textbook. Book Two simulates the effect of charred paper, of a cover page partially burned at the seams by the searing heat of the flaming bus, while Book Three even has small splotches of red splattered over the right-hand side of the image as well as on the top and bottom, suggesting either a light effect (reflecting rays of the sun) irritating the quasi-photographic recording of the scene or non-diegetic bloodstains smudging the papery surface of the drawing. As such, they subtly immerse the reader in the historical moment, suggesting haptic sensations that might make the past seem alive through books that can bleed and burn. These books are meant to be used like Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a comic book published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1957 that served as a political primer and tactical handbook.Footnote 53

Moving from paratexts to the text proper, we may note that March establishes a network of references that contextualize the narrative and communicate historical awareness. The books facilitate further research by including a list of dos and don'ts Lewis composed to provide members of SNCC with protest guidelines and by reprinting the reverend and civil rights activist Jim Lawson's statement of purpose for SNCC.Footnote 54 They also incorporate declarations by southern segregationists like Birmingham chief of police Eugene “Bull” Connor and Alabama governor George Wallace, as well as passages from political speeches by Lewis, King, and fellow civil rights advocates.Footnote 55 Book Three devotes seven pages to Fannie Lou Hamer's televised testimony at the Democratic National Convention in 1964, which follows speeches by New York governor Nelson Rockefeller and Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater at the Republican Convention.Footnote 56 Frequent radio announcements, television broadcasts, and newspaper headlines underscore the trilogy's claim to accuracy and suggest an archive of recorded and printed materials waiting to be accessed by readers in search of a better understanding of the movement.

Moreover, March evokes the sounds of the movement. In Book One and Book Three, protesters sing “We Shall Overcome,” the movement's anthem, whose lyrics express the pining for a life in peace and voice a belief in eventual triumph over racism.Footnote 57 Powell's depiction of the song includes snippets of the lyrics that visualize the singers’ dedication to a common cause and their affirmation of community, which are captured by the promise to walk hand in hand. He accomplishes this through singing balloons, or bands, that meander across the page and connect people via visualized sound. These bands function as a leitmotif that we can recognize as a stylistic device Powell had introduced in The Silence of Our Friends, but they also manage to retell a familiar story. They remind us that any account of the movement should include the music that sounded the fears and hopes of the protesters and infused them with the resolve to withstand physical and mental abuse.Footnote 58 The final stanza of “We Shall Overcome” clarifies the connection between future and present, aspiration and action. When the lyrics state that the singers are not afraid today, they mark the moment when the hymns’ spiritually grounded hope for a better time in heaven transitions into an expression of earthly resolve.

From a present-day perspective, such references to the music of the movement may seem overly optimistic, especially since they support a teleology that ends with Obama's inauguration. With Obama President, the message seems to be, the protesters have finally overcome the burdens of the past. They are no longer barred from voting in the South but have helped elect the first black President. Book One, Chaney notes,

closes on a note of optimism, of narrative and affective simplicity. The problem at the beginning, of there being no voice loud or legible enough, is solved in the end. Whose American voice speaks louder than that of our black president? History is progressive in this formulation … and it is also optimistic in a conservative way, perhaps even a radically conservative way. Social problems are to be solved by the official political system.Footnote 59

Yet as Chaney acknowledges, history in March is not always linear, and the musical references underscore a sense of nonlinearity. In jail, the protesters sing to preserve their dignity and irritate the guards. Singing becomes audible as a nonviolent form of resisting dehumanization, creating solidarity among the inmates.Footnote 60 It transforms linear prison time, meant to force them into submission and accepting racial segregation by arresting their ability to act on their beliefs, into nonlinear protest time, subjectively shortening the jail experience by investing it with a transcendent purpose.

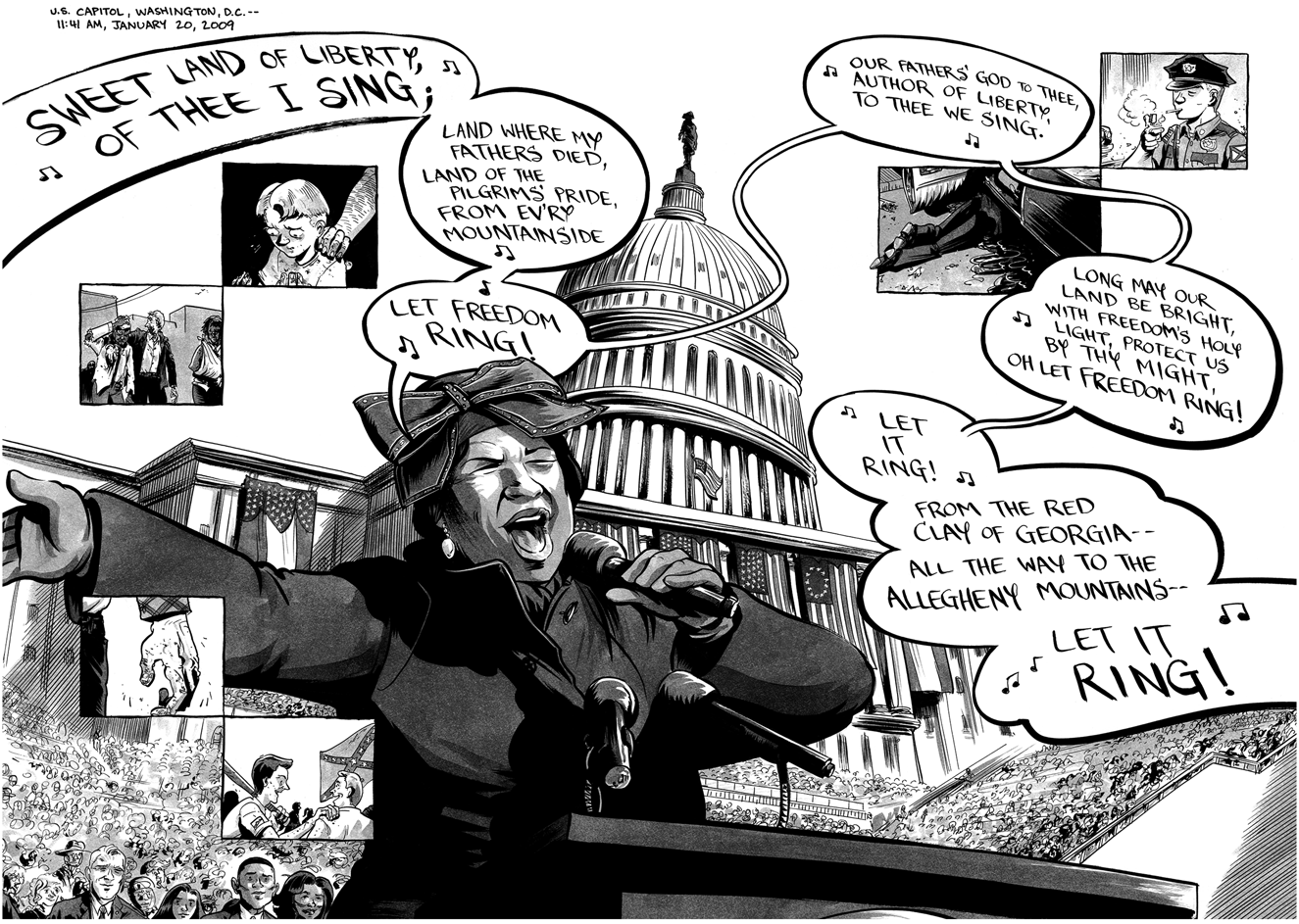

The most politically resonant musical reference occurs in Book Two, when soul singer Aretha Franklin performs “My Country ’Tis of Thee” at Obama's inauguration.Footnote 61 Not only does the phrase “let freedom ring” echo King's “I Have a Dream” speech, but while the patriotic lyrics are flowing from the top left of page 80 to the lower right of page 81, the narrative of American greatness is undermined by six rectangular inset panels (Figure 5). These panels document the historical sacrifices of the activists and the violations of the nation's foundational creeds by the segregationists. On the page that precedes Franklin's depiction on the steps of the US Capitol, the song's titular opening line appears across the post-protest carnage at a Greyhound station in Montgomery, where a white mob had attacked a group of protesters in 1961. Powell uses the same technique again directly afterwards. As we turn the page, the line “Oh let freedom ring!” carries us from the image of the singing Franklin in the narrative present to the throwing of a Molotov cocktail in the past. According to the sequential logic of comics, Franklin is pointing back to the past, signaling a need to remember history, whereas the white hand that throws the bomb gestures into the future and thus reminds us that it would be foolish to believe that American racism has been overcome. Musical representation therefore complicates the notion of linear time and the hope for a progressive movement toward a better America.Footnote 62 History is linear as well as circular: “Rather than creating paradox,” Chaney suggests, “that seeming contradiction reveals how our conception of past experience depends upon circularity, recursivity, even simultaneity.”Footnote 63

Figure 5. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

DIDACTIC IMPLEMENTATION

Asked about “how to use March – whether to teach it as a primary or secondary source, or something in between,” Andrew Aydin downplayed the interviewer's pedagogical challenge:

we worked really hard to make sure that every detail was as accurate as possible. We've been in contact with at least a dozen of the photographers from the movement. You know, folks who were there during the March on Washington, who were there during the early days and the later days. We used an incredible amount of reference photos to make the visuals as accurate as possible.Footnote 64

Aydin's touting of historical veracity clashes with the trilogy's more complex negotiation of media images, personal memory, and collective testimony. If the movement is “the most documented, photographed, and televised political phenomenon in US history,”Footnote 65 then achieving historical accuracy must be more complicated than Aydin suggests. After all, the polyphony and polysemy of available images and their incessant remediation make it impossible to reconstruct any singularly authentic narrative. Moreover, if we approach the trilogy from a metacritical perspective that recognizes its repeated remediation of already mediated images, we must go beyond notions of verisimilitude and develop a metacritical pedagogy that is aware of its active role in (re-)shaping public memories of the movement.

Engagements with civil rights memory inevitably participate in “a process of negotiation … in which meaning of the movement is constantly remade.”Footnote 66 The discrepancy between Lewis's Superman-inspired promotion of the narrative as an entertaining work – “it's dramatic. It's alive, it's movement, it's action”Footnote 67 – and Aydin's insistence on its documentary ethos certainly points to larger questions about “memorializing the movement” that prove especially vexing “in the arena of popular culture.”Footnote 68 But these questions are no less vexing in the realm of education, where instructors must make difficult, and politically volatile, decisions about how to frame their lessons and how to access movement historiography with their students. According to Lewis, the books specifically target educators – “It's a lot of fun to get out and talk about this book, and to see the reaction of people, especially teachers, librarians and children”– who might embrace the book as a welcome opportunity to teach their students about American history.Footnote 69

Indeed, judging from the wealth of teaching guides, March is widely present in American high schools and at colleges and universities, which is not surprising considering the popularity of graphic novels and the pedagogical prominence of civil rights history.Footnote 70 Top Shelf Productions even published its own teacher's guide, aimed at Grades 6–12 and “extensible to higher education,” which didacticizes March in a way compatible with state and national curricular standards. The guide includes before-reading, during-reading, and after-reading activities, as well as worksheets, discussion questions, and links to online sources.Footnote 71

What's more, the books already come with their own didactic devices, as events, places, and people are explicitly named to encourage further research. Book One includes a portrait of Lewis in profile in front of a black background as he is contemplating a powerful message from Jim Lawson. Three short sentences – “His words liberated me. I thought, this is it … This is the way out” – hover above Lewis's head, and the page design could be taken as an inspiration for student-created single-image portraits of civil rights figures and sentiments associated with them.Footnote 72 Book Two contains biography pages of A. Philip Randolph and Malcolm X that can be used as a model for assignments to produce similar pages for other members of the movement.Footnote 73 Book Two also reprints the original draft of Lewis's speech at the March on Washington, which students could contrast with the less confrontational speech he actually delivered.Footnote 74 The inclusion of the draft points to the larger project of the trilogy, which is to reiterate, in a popular medium, the “consensus memory” of the period,Footnote 75 while also “depict[ing] what is missing from the master narrative.”Footnote 76 As such, the March books are particularly valuable teaching tools that may use the students’ familiarity with “the deeply flawed version of the movement” taught around the country as a starting point for a more critical engagement with the historical material and its many mediations and remediations.Footnote 77

Such critical engagement could include considering lesser-known members of the movement, such as voter registration organizer Bob Moses, one of the central figures behind the March on Washington; the openly gay Bayard Rustin, another key organizer; as well as women activists like Ella Baker, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Margaret Moore, all of whom March depicts. Asking whether the trilogy goes far enough in addressing the “hidden meanings [and] omissions” of the master narrative and in supplanting its male hero specter with “a multiplicity of participants across time, gender, socioeconomic backgrounds, and races,” could lead to productive class discussions.Footnote 78

A particularly fruitful way to approach the books would be to follow the archival traces created by their intertextual and intermedial references. Of course, readers must be at least aware of this archive before they can “locate the many pasts of Lewis's trilogy, its multiple presents, and complicated racial futures,”Footnote 79 but the books themselves are fairly explicit about which lines of inquiry to pursue. The story of the freedom rides told in Book Two could launch an investigation into the history and iconography of the movement. The fact that its memorialization includes concrete objects offers opportunities to explore the material legacy and continuing visualization of this historical period. Think of the popular photograph of Rosa Parks, taken by a UPI photographer on 21 December 1956 as an emblem of the Montgomery bus boycott, or of the photograph of the blazing Greyhound bus near Anniston, remediated on the cover of March: Book Two. Books aimed at young readers like The Story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Photographs by David Aretha, and Faith Ringgold's If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks, offer additional material for analysis and creative engagement.Footnote 80 Another option would be to turn to autobiographical narratives shedding light on areas of the movement that are not commonly included in mainstream historical accounts. Sarah E. Gardner suggests Anne Moody's Coming of Age in Mississippi and Deborah McDowell's Leaving Pipe Shop: Memoirs of Kin as works that grant insights into the lives of people who were not directly active in the movement.Footnote 81 “Not everybody participated in sit-ins, went to jail, or was sprayed by fire hoses and attacked by dogs,” Gardner writes, emphasizing “aspects of black life that have been relegated to the margins” and could be salvaged through comparative reading assignments.Footnote 82

In addition to these prose autobiographies, graphic memoirs can support as well as challenge the March trilogy. Lila Quintero Weaver's Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White offers a Latinx perspective on the struggle for racial integration in Alabama, including the shooting and subsequent death of Jimmy Lee Jackson, which intensified the urge to march to Selma. Created by an Argentinian immigrant whose parents moved to Marion, Alabama when she was five, Weaver's account troubles the black-and-white binary of established movement historiography, introducing “a sliver of gray into the demographic pie” that had previously been “neatly divided between black and white.”Footnote 83 Turning to Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell's The Silence of Our Friends, a semiautobiographical account of a black and a white family in Texas in 1968, offers multiple opportunities for contextualizing the March books. For one thing, this graphic narrative about the friendship between the white television reporter John Long and the college instructor and black activist Larry Thompson (and their families) is told primarily from the perspective of the white reporter. The book thus raises pertinent concerns about interracial solidarity, and it also moves the action beyond the Deep South into a region not usually at the center of civil rights memory.Footnote 84 Moreover, since it is drawn in a graphic style that is largely identical to March and introduces visual vocabulary that also shapes the trilogy, The Silence of Our Friends reminds us that graphic renditions of the movement are aesthetic and narrative constructs that create the movement even as they seek to document it.

Like the March books, Darkroom and The Silence of Our Friends fashion the story of the movement as an account of its mediation, with Weaver taking her father's passion for photography and filming and the resulting visual archive as a pretext for thinking about the ways in which these technologies impacted the documentary record and shape the narratives afforded by this archive – including scenes in her father's darkroom where we witness the process of developing photographs, recollections of rewinding film footage, and an attempt to retell the events of the night when Jimmy Lee Jackson was killed and “nobody at all got a shot of what happened just one block from our house, on February 18, 1965.”Footnote 85 Like Darkroom, The Silence of Our Friends repeatedly shows camera equipment, and it also remediates television footage of the protests, encapsulating the images in panel frames shaped like television screens and showcasing events that remained unrecorded. When a policeman is killed by a ricocheting bullet during a protest, five black students are put on trial for murder, and the case is decided not on the basis of John's camera footage, which did not capture the moment, but on the grounds of John's eyewitness testimony. Both graphic narratives thus emphasize the need to fill gaps in the documentary record with creative nonfiction that draws on various forms of evidence and is also willing to imagine, and graphically represent, what may be missing from the story.

In a college or university setting, frame theory could anchor the analysis. Robert M. Entman defines framing as “essentially involv[ing] selection and salience. To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.”Footnote 86 Referencing Entman, Schmid suggests that frames “‘diagnose, evaluate, and prescribe’ an event or situation and thus assign causalities, roles, and relations to the actors and objects involved.”Footnote 87 In the March books, framing includes the heroic scope of the narrative, and its religious (occasionally messianic) iconography, as well as its political agenda of celebrating nonviolent resistance.Footnote 88 It occurs most forcefully in the celebration of “good trouble” as the most effective form of protest in opposition to more aggressive forms as advocated by Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, or Angela Davis, who offered more devastating views of the US and its state institutions than did Lewis. Confronting the text with less heroic, less religiously invested, and less male-centered perspectives, both from the civil rights movement and from our current moment, could facilitate a critical approach to the trilogy without necessarily undermining its narrative achievements. Focussing more specifically on the contributions of women, as M. Bahati Kuumba demands as a way of “looking between the cracks” of the master narrative, could reveal additional forms of “submerged activism” conventionally hidden by the male-centric gender politics of civil rights historiography.Footnote 89 One outcome of these confrontations and new perspectives could be that students learn to recognize structural similarities between the debates within the older civil rights movement over the right course of action and past and current doubts about the effectiveness of peaceful protest, as well as about what Hall calls “the triple oppression of black women – by virtue of the race, class, and gender” – in and beyond the movement.Footnote 90

There is, however, a media-specific aspect we must consider as we think about teaching March. In comics, framing takes a particular form, as Hillary Chute maintains: “while all media do the work of framing, comics manifests material frames – and the absences between them.”Footnote 91 Entman's processes of “selection and salience” constitute the basic narrative grammar of comics: the panel border as a frame that has a particular effect on the reader, or the page or double page as a materially framed narrative unit, or shifting points of view as conveyors of meaning. What is selected as the content of a panel and what is excluded are fundamental decisions routinely made in the sequential structuring of the narrative and ensuing acts of closure. Here, Hall's observation that

remembrance is always a form of forgetting, and the dominant narrative of the civil rights movement – distilled from history and memory, twisted by ideology and political contestation, and embedded in heritage tours, museums, public rituals, textbooks, and various artifacts of mass culture – distorts and suppresses as much as it reveals

is particularly pertinent, as graphic narrative is predisposed to visualize the tension between historical suppression (the gutter) and new acts of revelation (the panel).Footnote 92

The confrontation on Bloody Sunday between the protesters and the Alabama state troopers in Book Three uses extensive framing to drive home the books’ overall message. It presents an ideal occasion for investigating not only the contents of the narrative but also the mechanisms through which March memorializes the movement and the political implications that follow from this memorialization. In particular, we can detect a shift from the earlier depiction of movement photography, exemplified by Lyon's Cairo photographs and SNCC's poster as cases of self-controlled image-based agitation, to the “seductive new medium of television” and its less regionally grounded and less grassroots-oriented production and dissemination of moving images. Bloody Sunday was covered by the major news networks and reached a national viewership when the reporting aired on prime time. If the civil rights movement was the networks’ “first major ongoing domestic story,” then Bloody Sunday was a “point of maximum visibility for the [Selma] campaign as a national news event.”Footnote 93 Rather than take the television images as documentary raw material against which to assess the depiction in March, students should achieve a critical consciousness about these images. They can improve their media literacy by recognizing that the television reportage was part of an ongoing interaction among television networks, the movement activists, and southern segregationists, playing out in front of a national audience. For movement leaders like Lewis and King, television was a powerful platform for presenting their case to the American people, even though they had little control over which images were broadcast and how they were framed.

Eleven days after Bloody Sunday and under the impression of television images that showed policemen in Montgomery attacking a mixed group of student protesters on 17 March, King told reporters, “We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We're going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.”Footnote 94 The news networks also had a vested interest in broadcasting these images to the nation as they “shared [an] urgent desire to forge a new, and newly national, consensus on the meanings and functions of racial difference.”Footnote 95 They thus framed the conflict in a double sense. They added the media-specific frame of the television camera but also presented the events through the lens of a particular political narrative, both of which shaped the “selection and salience” and “moral evaluation” of the imagesFootnote 96 – processes that the March books acknowledge by framing well-known footage with the apparatus of the television set.

Before students analyze the depiction of the events in March: Book Three, they should read up on this crucial backstory. These readings (which are always also framings and should be recognized as such) could include Sasha Torres's Black, White, and in Color: Television and Black Civil Rights, Aniko Bodroghkozy's Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement, or Danielle Smith-Llera's TV Exposes Brutality on the Selma March: 4D an Augmented Reading Experience, the last of which includes original television footage that could be used for further analysis.Footnote 97 The recently launched interactive website www.selmaonline.org, created by the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, provides intriguing digital inroads into civil rights history. In addition, students should familiarize themselves with comics narratology so that they can identify the intricacies of sequential storytelling and perform the mental processes of closure. Teachers can introduce key terminology and practice its application before turning to March, but they can also use central scenes of the graphic memoir to train their students in basic comics literacy.

Yet how exactly does March: Book Three “diagnose, evaluate, and prescribe” Bloody Sunday as a historical moment of maximum visibility from the vantage point of the present?Footnote 98 How does it use this moment to memorialize the movement? It begins by segmenting the account into a sequence of double pages that encapsulate the magnitude of the event and the individual perceptions of the marchers and onlookers through specific panel arrangements and shifting perspectives. The first of these double pages presents a symbolically charged appearance of the bulging Edmund Pettus Bridge.Footnote 99 The bridge is shown on the upper third of page 196 from a somewhat removed perspective, as we are witnessing the marchers making their way to the top. On the upper half of page 197, we are already on the bridge, placed in a slightly elevated over-the-shoulder position that moves us closer to the marchers, who are looking down the declining bridge at the troopers blocking their way. These ascending and descending views of the bridge can be decoded as a reference to drama's rising and falling action; they indicate that the narrative is about to reach its climax and signal that we are entering a particular framing of the depicted events. More significantly, the first image of the bridge foregrounds a press photographer covering the confrontation, which is also why we can interpret (via closure) the second image as a representation of this photographer's point of view or a view close to it. Yet the other panels on the page do not endorse any single perspective; they zoom in and out of the action, combining alternating close-ups of the marchers’ faces and the conversation between Hosea Williams and John Lewis with panorama shots of the scene and moving from the protesters’ position to the location of the state troopers.

These perspectival shifts suggest a variously photographic, televisual, and cinematic approach. They evoke this sense of photography, televisuality, and cinematography by remediating existing photographs and television footage to signal historical accuracy. The topmost panel on page 195, for instance, which shows the protesters advancing through Selma, is an almost exact remediation of one of Charles Moore's civil rights photographs.Footnote 100 The only differences, apart from the change in medium, are the absent background, which ascribes a sense of temporal transcendence to the image, and the fact that the long line of marchers already begins at the bottom of the preceding page, which underscores the sheer mass of people as well as the page-crossing, visually and politically transgressive, action. Yet the sequential arrangement of these scenes also suggests a filmic sensibility, an effective editing of images from different cameras that ventures beyond documenting the scene into the realm of cinematic dramatization. Ava DuVernay's Selma, released two years before March: Book Three, could serve as the basis for a comparison of Powell's mise en page and the filmic depiction of the encounter on the bridge.Footnote 101 Such a comparison could draw attention to differences in media-specific techniques – historically, in terms of movement photography and the televisual depiction of the struggle, as well as presently, in terms of how film and graphic nonfiction memorialize the events.

Pages 198 and 199 bring us even closer to the action, placing us between the protesters and the troopers (Figure 6). They begin by showing the troopers putting on their gas masks and ordering the marchers to disperse. Oversized lettering and scraggly balloons indicate the harshness of the orders. The double page contrasts the aggressive demeanor of the troopers with the peaceful and dignified conduct of the protesters, who react to the commanding officer's denial of their request to speak with the major – “There is no word to be had” – by kneeling down and praying.Footnote 102 The penultimate panel on this page conveys a sense of quiet resolve in the pivotal moment by evacuating everything except the marchers from the image. All of the surroundings, including the panel frame, have disappeared; what counts is the spiritual preparation for what is to come. In McCloud's terms, this missing panel frame is a “bleed”: a visual marker that signifies meaning through conspicuous absence. Bleeds occur “when a panel runs off the edge of the page … [and] time is no longer contained by the familiar icon of the closed panel, but instead hemorrhages and escapes into timeless space.”Footnote 103 The March books use panel bleeds to suggest the timelessness of the civil rights movement as a struggle for social and racial equality that cannot be confined to a limited period of US history.Footnote 104

Figure 6. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

The final panel on the page affords a moment of rest to the protesters and the reader, a piece of calm before the storm about to unfurl as we flip the page. The image is devoid of sound and movement and gives no indication of its duration. It visually captures the fact that the “movement's most consistent and effective gesture against segregation was to contrast the racial terrorism of the South with national ideals and democratic discourses.”Footnote 105 In terms of framing the struggle, the image not only pits the praying protesters against the armed and masked state troopers but inserts between them three cameramen and/or news reporters. This is the third time on this double page that these media representatives appear. They accompany every step of this unfolding drama and raise questions about the instantaneous, real-time memorialization of the movement, including the fact that a photographer like Charles Moore was sometimes “close enough [to the demonstrators] that he wound up in the frames that other photographers were taking from farther away.”Footnote 106 Most significantly, they complicate the “ontological status” of the graphic presentation.Footnote 107 Are we reading a comic that is based on Lewis's memories or on the photographic and televisual images that the cameramen had recorded in 1965 and that Powell remediates to establish an authoritative depiction? Can there even be unmediated memories of these moments? What is the connection between the graphic narrative, the historical images on which it draws, and Lewis's recollection of the events, already presented in Walking with the Wind and recounted many times since the mid-1960s? What other eyewitness accounts contributed to the construction of the scene, and what did the photographers Aydin consulted add to the story? All of these questions are useful prompters for classroom activities, from a comparative close reading of Walking with the Wind and March to cross-media analysis of movement photography, moving images, and graphic narrative.

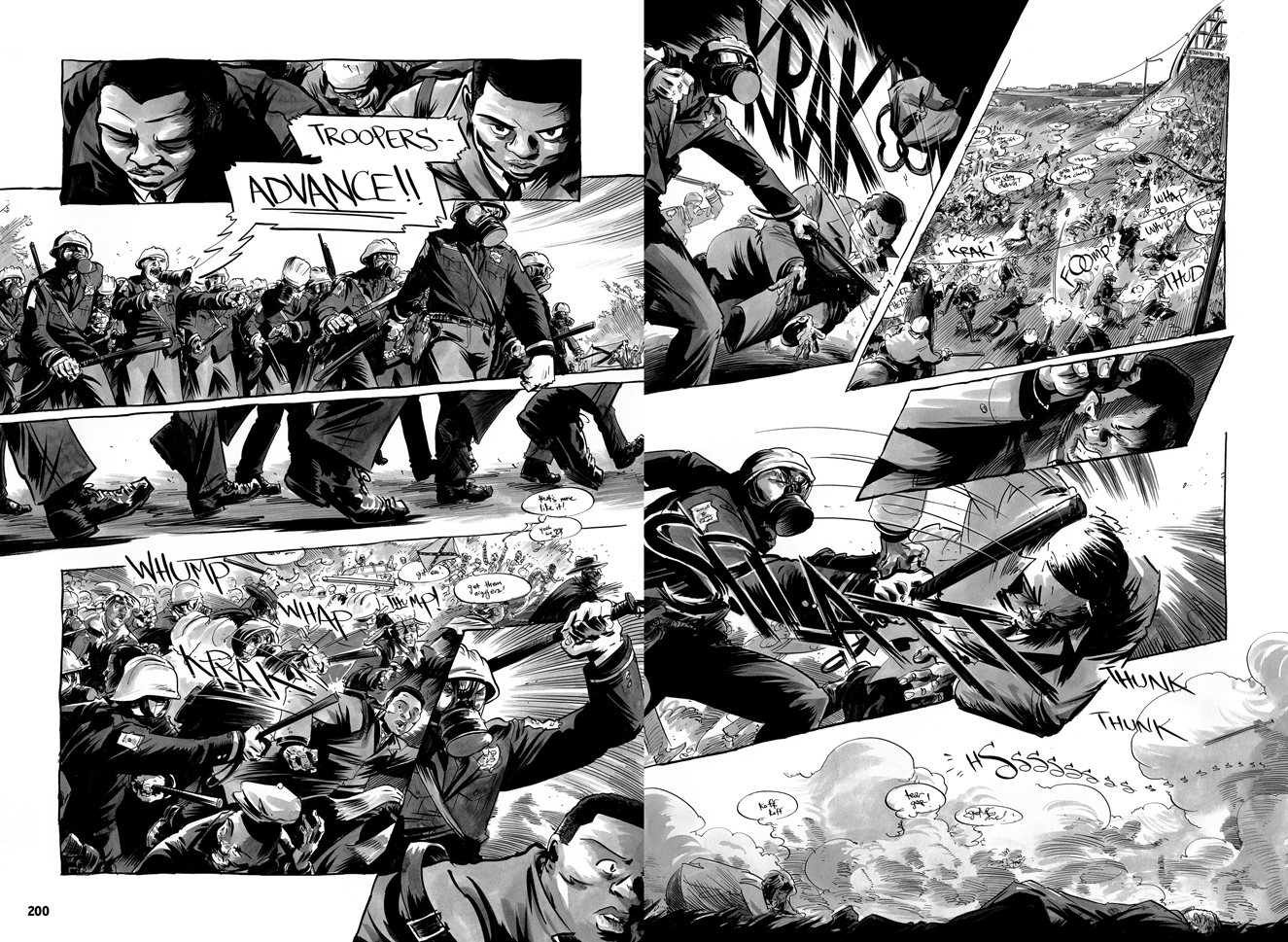

Pages 200 and 201 zoom in even closer to the action (Figure 7). The first page depicts the transition from prayer to physical violence; the second shows the initial attack, focussing on Lewis as he is beaten and falls down, his backpack flying through the air. The troopers emerge as the aggressors here, as their leader issues the order for the attack (“Troopers – advance!!”) and as they use batons and tear gas against the unarmed protesters. In terms of layout, the relatively ordered structure of the preceding pages gives way to a more crowded, hectic panel arrangement. These panels’ increasingly irregular shapes evoke a sense of brokenness, like shards of glass splintering from a smashed window. It is as if the images are bursting out of the sequence suggested by conventional comic-book narrative, as if they were shattering a television screen that can no longer contain these horrific events. Viewpoints oscillate between extreme close-ups of Lewis's face, medium shots juxtaposing legless troopers with the marchers’ metonymic feet, and long shots simulating the confusion of the moment while affording us a more distanced view of the carnage. While the storytelling is effective in its attempt to immerse the reader in the depicted action, its cinematic qualities as well as the manga-style sound words (“KRAK,” “SPLATT”) mark its indebtedness to the conventions of popular storytelling.

Figure 7. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

The next two pages are even more explicit in their remediation of cinematic strategies (Figure 8). Switching from close-ups of Lewis's battered face and head as he is losing consciousness to an unframed subjective shot that shows complete darkness except for the words “I thought I was going to die” in white letters, the narration offers a moment of internal focalization, where we become privy to Lewis's (recollected) thoughts.Footnote 108 The opposite page zooms out again, supplanting the blackout scene with a high-angle shot of Lewis slowly coming to his senses, and then zooming back in again. “Get up. Keep moving,” read the words accompanying these visuals, changing the narrative situation from the first-person narrator's retrospective “I thought I was going was going to die” in block letters to character speech in cursive.Footnote 109 Paying attention to these details matters, since they shape our interpretation of the history constructed by the narrative as well as its emotional impact. Employing more or less subtle means of telling the story of the civil rights movement and of (re-)memorializing already heavily mediatized events for new audiences in a new medium, the March books definitely reward such a closer look.

Figure 8. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

POLITICAL FAILINGS AND HISTORICAL FETISHES

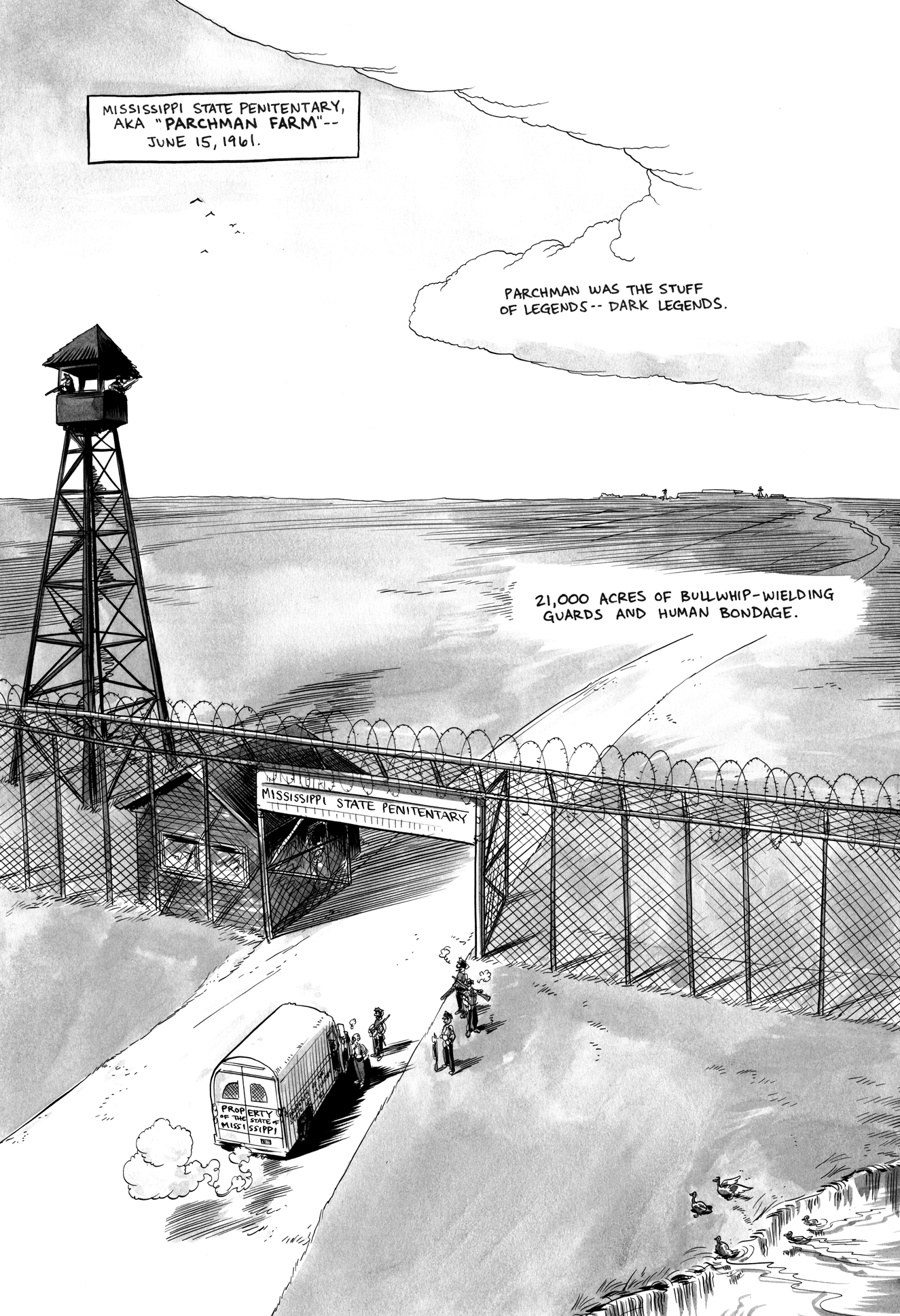

By advocating attention to its mediation and remediation of history and identifying the framing mechanisms at work in March, I do not mean to absolve this graphic memoir from its “political failings and historical fetishes.”Footnote 110 In fact, I would argue that these failings and fetishes are instructive in their own right and can serve as teachable moments. I have already mentioned the books’ partial reiteration of the movement's master narrative as reason for critique, but I want to close with brief analyses of selected splash pages in Book Two that further trouble overly enthusiastic readings of the work. The first of these pages shows a bus carrying a group of black prisoners to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as “Parchman Farm” (Figure 9). The prison is described as “21,000 acres of bullwhip-wielding guards and human bondage,” and the accompanying image recalls photographs of Nazi concentration camps, suggesting at least a tenuous connection between the Holocaust and the suffering of African Americans in the Deep South, represented by guards that greet the freedom riders from a watchtower with their rifles drawn, a massive fence topped with barbed wire, and a sign over the entrance gate stating “Mississippi State Penitentiary” (versus Auschwitz's “Arbeit macht frei”).Footnote 111 On the immediately preceding page to the left, the prisoner's clothes, called “ring-arounds” and documented in many historical photographs,Footnote 112 recall the uniforms of concentration camp inmates. Taken together, these visual references to the Holocaust and the depiction of the freedom riders’ initiation into the prison – they are ordered to undress, forced to shave, and then compelled to put on prison clothes, with the narrator calling the whole process “dehumanizing” and “part of an effort to strip away our dignity”Footnote 113 – establish a simultaneously powerful and potentially fraught analogy between the century-long oppression of African Americans and the genocide of the European Jews.

Figure 9. March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy Top Shelf Productions/IDW Publishing.

The analogy is powerful because it embeds the depiction of the civil rights movement in a longer history of systemic unfreedom, from the slaves’ bondage to the Holocaust to Parchman's status as “the quintessential penal farm, the closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War,” and an embodiment of a “powerful link to the past – a place of racial discipline where blacks in striped clothing worked the cotton fields for the enrichment of others.”Footnote 114 In addition, by stating that “Parchman was the stuff of legends – dark legends,”Footnote 115 Lewis and his collaborators conjure up the prison's symbolic significance as a testament to what David M. Oshinsky describes as “the ordeal of Jim Crow justice” in the subtitle of his study on the subject. In terms of teaching methodology, the visual evocation of the Holocaust could be used as a prompt to discuss the March books alongside Art Spiegelman's seminal MAUS and other Holocaust comics, while the imprisoned freedom riders’ singing could prepare the ground for exploring Parchman's appearance in classic blues songs by Son House, Leadbelly, and Bukka White.Footnote 116

Yet the analogy between Jim Crow and the Holocaust, Parchman and Auschwitz, as subtle as it may be, is also fraught because it threatens to obscure the historical specificities of each event and might manipulate the reader's emotions by tapping into a transhistorical and transnational image archive – watchtowers, armed guards, fences and barbed wire, prison gates, dehumanized inmates. But then again, thirty-one prisoners, twenty-three of them black, were sent to the gas chamber at Parchman between 1954, the year of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and 1964, when the nationwide moratorium on capital punishment began.Footnote 117 Perhaps the analogy between the Jim Crow prison and Nazi concentration camps is less far-fetched than it may seem at first glance, reminding readers, as Ta-Nehisi Coates claims for African Americans, that you “cannot disconnect our emancipation … from Jim Crow from the genocides of the Second World War.”Footnote 118 Nonetheless, this scene and the many other jail scenes that place movement activists behind bars are never connected with the sprawling prison–industrial complex and today's mass incarceration of American Americans, which creates a certain disconnect with present concerns.Footnote 119 Delving into these difficult issues could encourage students to think not just beyond the southern focus of civil rights memorialization but also beyond its preoccupation with national American history.

At an earlier point in the narrative, a white segregationist throws a stone through a stained-glass window of the 16th Street First Baptist Church in Montgomery. It leaves a hole that obliterates Jesus Christ's head and thus symbolically categorizes the segregationist mob as un-Christian and the black activists as good Christians (recalling the framing of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself).Footnote 120 This somewhat heavy-handed symbolism takes on a more suggestive dimension in the very last scene of Book Two. The scene depicts, in a rather cryptic fashion that presupposes a reader who is either aware of civil rights history or willing to research the missing context, the bombing of First Baptist Church in 1963 by members of the local Ku Klux Klan organization that killed Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair. This four-page sequence moves from Obama's inauguration speech to a man in a phone booth (connected by the notion of “sacrifices borne by our ancestors” in the speech balloon that crosses the pages), to the actual bombing and its aftermath.Footnote 121 Here, Jesus’ missing face occurs again, but this time his heart has been crushed by the blast. The message is certainly sentimental, but it is also powerful because the not-so-subtle symbolism of the stained-glass window is accompanied by the smoke from the explosion, the sirens of police cars and ambulances, and two words in a brittle speech balloon: “Denise? Addie?”Footnote 122 Completing the act of closure, we are forced to come to terms with the fact that there can be no satisfying response to these words and that all we can do is develop our own response and formulate our own answers to this call for compassion – both as teachers and as students of the civil rights movement and its contested legacies.