In November 2019, the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development consortium communicated that previously released functional MRI data from Philips scanners has been processed incorrectly and should not be analyzed. The resting-state fMRI analyses reported in Thijssen et al. (Reference Thijssen, Collins and Luciana2019) include data from Philips scanners. We have reanalyzed our resting-state fMRI data excluding participants scanned on a Philips scanner (n = 256). Excluding the Philips data did not significantly affect our results. For the new results, please see below. The conclusions described in the manuscript remain unchanged.

Resting-state fMRI

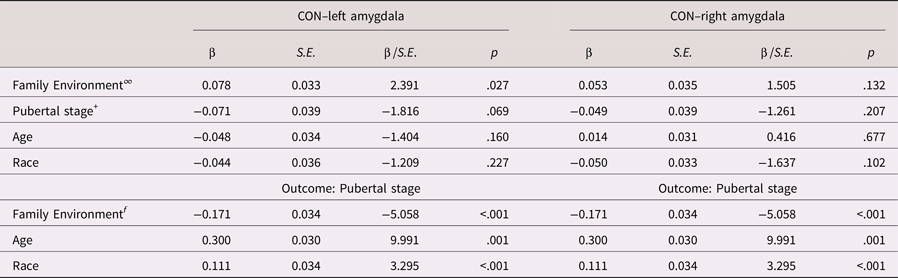

In the total sample excluding those scanned with Phillips scanners, the total, direct, and indirect effects of Family Environment on cingulo-opercular network–left amygdala functional connectivity were β = 0.068, p = .003, β = 0.059, p = .010, β = 0.009, p = .071, respectively. For cingulo-opercular network–right amygdala functional connectivity, the total, direct, and indirect effects were β = 0.044, p = .055, β = 0.036, p = .122, β = 0.008, p = .106, respectively. Thus, Family Environment was positively associated with cingulo-opercular network–amygdala functional connectivity. For the left amygdala–cingulo-opercular network functional connectivity, the indirect effect of family environment on functional connectivity via pubertal stage indicated a trend in the expected direction. For right amygdala–cingulo-opercular network functional connectivity, the indirect effect no longer indicates a trend (p > .1). As the effect size of the indirect effect increased from β = 0.007 to β = 0.008 when excluding the Philips data, this difference is solely explained by decreased power.

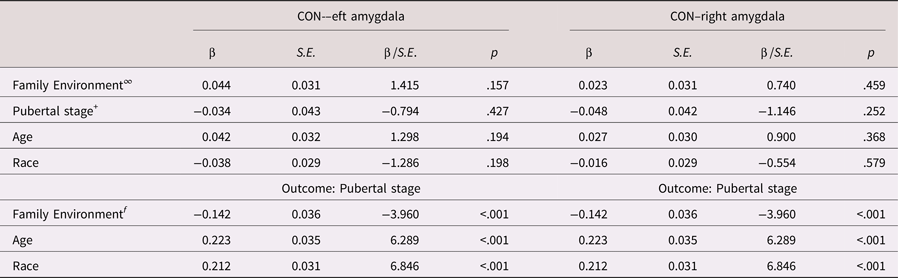

The exploratory analyses stratified by sex suggest that the total and direct effects of Family Environment on cingulo-opercular network–left amygdala functional connectivity were significant for girls, whereas a trend was found for the indirect effect (β = 0.090, p = .005, β = 0.078, p = .017, β = 0.012, p = .093, respectively). For boys, no significant effects were found (β = 0.049, p = .112, β = 0.044, p = .157, β = 0.005, p = .459, respectively). For cingulo-opercular network–right amygdala functional connectivity, no significant effects were found for girls nor boys (girls: β = 0.061, p = .071, β = 0.053, p = .132, β = 0.008, p = .226 for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively; boys β = 0.030, p = .322, β = 0.023, p = .459, β = 0.007, p = .289, for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively).

Table 6. Mediation model parameters––Cinculo-opercular network–amygdala connectivity

Note: CON = cingulo-opercular network; ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1.

TableS9. Mediation model parameters––Cinculo-opercular network–amygdala connectivity in girls

Note: ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1; CON = cingulo-opercular network.

TableS12. Mediation model parameters––Cinculo-opercular network–amygdala connectivity in boys

Note: ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1; CON = cingulo-opercular network.

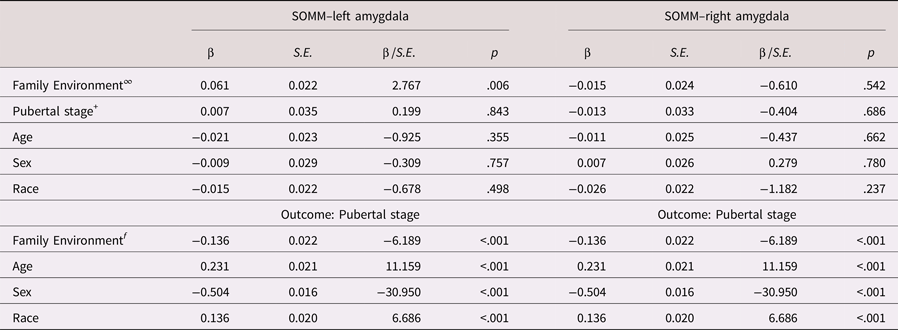

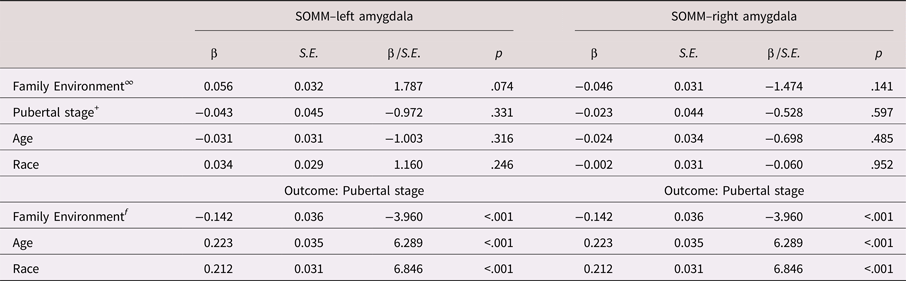

Somato-motor mouth network–amygdala functional connectivity

For the resting-state model with motor processing measures, onlythe total and direct effects of Family Environment on SOMM–left amygdala FC were significant (β = 0.060, p = .005, β = 0.061, p = .006, respectively), but not the indirect effect (β = −0.001, p = .847). No associations between Family Environment and SOMM–right amygdala were found (β = −0.013, p = .583, β = −0.015, p = .542, β = 0.002, p = .693, for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively).

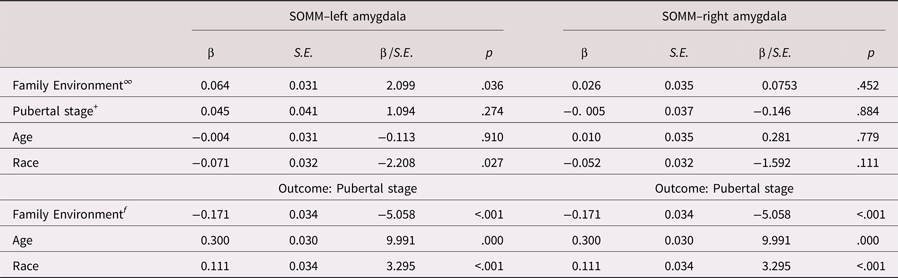

For the resting-state model with motor processing measures, in girls the total and direct effects, and in boys only the total effect of Family Environment on SOMM–left amygdala FC were significant (girls: β = 0.056, p = .048, β = 0.064, p = .036, β = −0.008, p = .302 for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively; boys β = 0.063, p = .041, β = 0.056, p = .074, β = 0.006, p = .357. for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively). No significant associations were found between Family Environment and SOMM–right amygdala (girls: β = 0.027, p = .421, β = 0.026, p = .452, β = 0.001, p = .886 for total, direct, and indirect effects,respectively; boys β = −0.043, p = .157, β = −0.046, p = .141, β = 0.003, p = .606 for total, direct, and indirect effects, respectively).

TableS6. Mediation model parameters––Somatomotor-mouth network–amygdala connectivity

Note: ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1; SOMM = somato-motor mouth network.

TableS17. Mediation model parameters––Somatomotor-mouth network–amygdala connectivity in girls

Note: ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1; SOMM = somato-motor mouth network.

TableS20. Mediation model parameters––Somatomotor-mouth network–amygdala connectivity in boys

Note: ∞ = direct effect; + = indirect effect Step 2; f = indirect effect Step 1.SOMM = somato-motor mouth network.

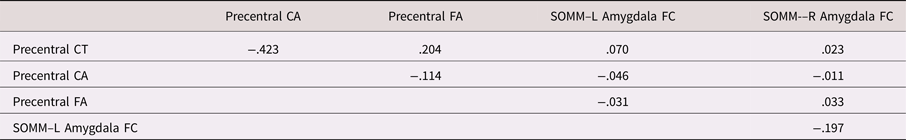

Table3. Correlation between MRI measures

Note: All measures are residualized for data collection site. Gray matter measures were further residualized for total brain volume. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; CT = cortical thickness; CA = cortical area; FA = fractional anisotropy; SC = subcortical volume; CON = cingulo-opercular network; l = left; r = right; FC = functional connectivity.

TableS1. Correlations among brain measures of motor processing

Note: SOMM = somatomotor-mouth network; FC = functional connectivity; CT = cortical thickness; CA = cortical area; FA = fractional anisotropy.