Background

Dementia is the leading cause of death in the UK and the seventh commonest cause globally (World Health Organization, 2017). More than 80 billion hours of care a year are provided annually by informal carers. Dementia caregiving can have significant emotional implications for family carers, and the experience of grief while the person with dementia is still alive, known as pre-death grief (Blandin and Pepin, Reference Blandin and Pepin2017; Lindauer and Harvath, Reference Lindauer and Harvath2014), is particularly common.

As knowledge about pre-death grief in the context of dementia caring has increased in the literature, terms used to reflect this experience have also evolved moving from the concept of “anticipatory grief” to pre-death grief, which can also be referred to as “dementia grief.” There are many overlaps between anticipatory grief and pre-death grief; however, pre-death grief relates to losses experienced rather than anticipated and is thought to better encompass the important facets of pre-death grief for this population (Blandin and Pepin, Reference Blandin and Pepin2017). Pre-death grief has been defined as “the emotional and physical response to the perceived losses in a valued care recipient. Family caregivers experience a variety of emotions (e.g. sorrow, anger, yearning and acceptance) that can wax and wane…from diagnosis to the end of life” (Lindauer and Harvath, Reference Lindauer and Harvath2014). Pre-death grief can occur due to the lengthy and uncertain dementia trajectory and can be triggered by losses associated with dementia such as compromised communication and changes in relationship quality and carer freedom (Lindauer and Harvath, Reference Lindauer and Harvath2014).

Bereavement and grief are a normal part of life; however, for a minority of people grief can interfere with everyday life and involve long-term severe reactions to the loss that impact on functioning. Researchers and clinicians have been attempting to differentiate between normative bereavement and pathological or disordered grief since the 1990s. A debate has ensued involving competing theoretical conceptualizations, diagnostic criteria, and psychometric measurement. The first diagnostic criteria for a bereavement related disorder were termed pathological grief (Horowitz et al., Reference Horowitz, Bonanno and Holen1993) which was then updated to Complicated Grief (CG) (Horowitz et al., Reference Horowitz1997). Different terminology has been used over time, but the terms CG and Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) have been most commonly used. Higher levels of grief prior to death are associated with PGD or CG after death (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Livingston, Jones and Sampson2013; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2014). PGD is characterized by symptoms such as longing for and preoccupation with the deceased, emotional distress, and significant functional impairment for at least 6 months after the loss (Killikelly and Maercker, Reference Killikelly and Maercker2018). CG, while a very similar concept to PGD, is characterized by intense grief that lasts longer than would be expected according to social norms and impairment in daily functioning.

PGD has been associated with poor physical health, suicidality, reduced quality of life, and functional impairment (Boelen and Smid, Reference Boelen and Smid2017). Although distinct from other mental health disorders, PGD can co-occur with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety (Boelen and Smid, Reference Boelen and Smid2017). While pre-death grief is not PGD, the intensity and duration of pre-death grief experienced by some may be consistent with definitions of PGD, and therefore research has begun to explore this using adapted versions of PGD measures (Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Moore et al., Reference Moore2017)

In response to advancing research evidence, grief disorders have been included in two diagnostic classification systems. The DSM-5 introduced Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder under the conditions for further study, which is a combination of PGD and CG criteria, while the International Classification of Disease 11th revision (ICD-11) introduced PGD as a disorder based largely on the PGD criteria proposed by Prigerson et al. (Reference Prigerson2009). For the purpose of this paper, post-death grief will be reported using the terminology used in the original studies, that is, CG or prolonged grief.

The most recent systematic review that synthesizes the prevalence and associated factors of pre-death, post-death, and prolonged/CG was published in 2013 (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Livingston, Jones and Sampson2013). The review included 31 studies, many of which were of poor quality, and included only 1 study reporting the prevalence of PGD. Studies exploring the relationship between pre- and post-death grief were also limited within this review. They found that moderate to severe stage of dementia predicted pre-death grief, while being a spousal carer and being depressed were the biggest predictors of both normal post-death grief and prolonged grief post-death. Poor quality evidence suggested that between 47% and 71% experienced pre-death grief, and around 20% experienced CG. Since this review of studies published until 2009, research has further explored the experience of grief. This, in turn, adding to our understanding of the prevalence and predictors of grief.

We do not know how many carers need support either before or after the death of the person with dementia. Current grief services tend to target those who have experienced a recent death. The current bereavement model in the UK suggests that most people manage with support from family and friends, and without the need for professional intervention. However, it is unclear whether this model meets the needs of carers of people living with dementia (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004). While the prevalence of CG is estimated between 10 and 20% (Lobb et al., Reference Lobb2010), one in three carers of people living with dementia was found to access bereavement services (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011) suggesting a higher proportion of carers seek professional support than the bereavement model indicates. It is also less known if carers of people living with dementia seek services for pre-death grief, although a recent study of current carers found that 30% had accessed formal counseling (Moore et al., Reference Moore2020).

In light of the newer definitions regarding pre-death grief, CG and PGD, and the wealth of research exploring these experiences, we aimed to update and extend the review by Chan (2013). We aimed to seek answers to the following review questions:

In family carers of people living with dementia:

-

1. What is the prevalence of pre-death and prolonged/CG and when does it become a clinical disorder?

-

2. What are the factors associated with pre-death and prolonged/CG?

-

3. In longitudinal studies, what is the relationship between pre-death factors and post-death prolonged/CG?

-

4. What services do carers use to manage grief?

This review does not examine effectiveness of grief interventions as this was addressed in a recent review (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson2017).

Methods

The review protocol CRD42020165071 was registered on PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews and followed PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

We initially planned to include qualitative studies and gray literature; however, due to the large volume of literature available we decided to limit our inclusion criteria to quantitative studies during full-text review.

Inclusion criteria

-

Type of studies: All quantitative studies or quantitative data from mixed methods studies. Studies were not excluded based on quality.

-

Topic: Grief prevalence, relationship between pre- and post-death grief, factors associated with grief and services used to manage grief.

-

Participants: Family or friend non-paid carers (aged 18 or over) of people with dementia.

-

Setting: Participants were providing care or support for somebody living with any type and severity of dementia in the community or in long-term care facilities. Bereaved carers were also included.

Exclusion criteria

-

Effectiveness of intervention data

-

Studies not written in English

-

Paid/professional carers

-

Qualitative data (excluded at full-text review)

-

Gray literature (excluded at full-text review).

Search strategy

We searched PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and ASSIA to April 2020. The search strategy was refined through test searches using medical subject headings and free-text terms. The search included keywords and terms associated with dementia, grief and family carers as shown in Supplementary File 1.

Selection of studies

Abstracts of identified citations were independently screened by two reviewers (either SC and KM, or SC and NK) to ensure consistency when applying the inclusion criteria. Interrater reliability of full-text selection was calculated using Cohen’s kappa (K) and ranged from moderate (93.3% agreement) to nearly perfect (97.8% agreement) between the author combinations (Landis and Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977). Full texts of citations were checked for eligibility by two reviewers, and any discrepancies resolved through discussion with all three reviewers.

Data extraction

Characteristics of the studies were extracted by SC into a table developed for this review. Extracted data included country of origin, study design, details of grief measurement tools used, participant characteristics, and results such as relationship between factors associated with and prevalence of pre- and post-death grief, and services used by carers to manage grief. Two authors (KM, NK) independently checked 20% of data extraction.

Quality assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018 revised version with improved content validity was used to assess the quality of included studies (Hong et al., Reference Hong2018). The MMAT appraises and describes the quality for three methodological domains: mixed, qualitative, and quantitative (subdivided into three sub-domains: randomized controlled, non-randomized, and descriptive). Authors are advised to present how studies meet the quality criterion appropriate to their study type. All studies were assessed using the tool, and 20% were checked by a second author (KM, NK, EW) with any discrepancies discussed and resolved.

Data analysis

The Cochrane framework for summarizing study characteristics and synthesizing data was implemented. At protocol stage, questions were defined, and planned analyses proposed; evidence for Q1 was synthesized based on the measure of grief and the cut-off scores used in studies. Q2 was addressed by summarizing associations with grief and exploring subgroup differences such as differences in carer and the person living with dementia characteristics and experience of grief such as gender, ethnicity, age, relationship to the person living with dementia, and dementia severity. Longitudinal evidence for Q3 was summarized to describe the impact of carer and care-related factors assessed before the death of the person living with dementia on post-death grief. Services used to manage grief were described to address question Q4.

Associations were tabulated and a narrative summary was provided of evidence from studies which met at least four out of five of the MMAT quality criteria. Associations were discussed within the narrative summary if there were at least three studies reporting a factor for pre-death grief, while all factors were discussed for post-death grief as there were fewer included studies. Where associations were reported, factors were discussed within domains which were identified from the evidence: demographic carer factors; psychosocial characteristics; person living with dementia and care-related factors; and bereavement factors.

Results

We identified 771 unique citations after removing 134 duplicates, of which 230 met our inclusion criteria for full-text review. Fifty-five quantitative and mixed methods studies were included. Only quantitative data were included from mixed methods studies as demonstrated in the PRISMA diagram (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

Sample size and characteristics

The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n = 33), seven in Europe, six in Singapore, three in Hong Kong, three in Canada, and one study each in Australia, Puerto Rico, and South Korea. Studies mainly consisted of spouse or adult child carers. Thirty-four studies reported dementia severity of the care recipient; 13 studies included moderate to severe dementia, 3 reported moderate, 3 reported advanced, and 10 included mild, moderate, and severe dementia. Forty studies reported pre-death grief, 11 post-death grief, 3 both pre- and post-death grief, and 6 service use. Eight of the 55 studies included longitudinal data. Pre-death grief was measured using the Marwit Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory (MMCGI) (n = 11), the MMCGI-Short Form (SF) (n = 14), the PGD Scale pre loss (PG-12) (n = 1), or the Inventory of PGD Scale short form pre-loss (n = 1). Disordered post-death grief was measured using the Inventory of Complicated Grief (n = 8) and the PGD Scale (PG-12) (n = 1), while normal post-death grief was reported using the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (n = 3) (Table 1).

Table 1. Key findings

AA, Alzheimer’s Association; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease; NH, Nursing home; MMCGI-SF, Marwit Mesuer Caregiver Grief Inventory-Short Form; FC, Family Carer; MMCGI BF, Marwit Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory Brief Form; AGS, Anticipatory Grief Scale; PDG, pre-death grief; PS, perceived stress; ADRDA, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association; LBDA, Lewy Body Dementia Association; PDD, Parkinson’s disease with dementia; DLB, Dementia with Lewy Bodies; GI, Grief Intensity; RMBPC, Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist; PE, Parameter estimate; REACH, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health; FaCTs, Family Caregiver Transition Support; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CG, complicated grief; NDRGEI, Non-Death Revised Grief Experience Inventory; SGI, Stage of Grief Inventory; CGS, Caregiver Grief Scale; MFG, Many Faces of Grief; TRIG Texas Revised Inventory of Grief.

a REACH (1996–2000 at six sites in the USA (Boston, MA; Birmingham, AL; Memphis, TN; Miami, FL; Philadelphia, PA; and Palo Alto, CA) Recruited through media, memory clinics, primary care clinics, and social services. Outreach efforts to the community at all sites included radio, television, targeted newsletters, public service announcements, and community presentations.

Quality appraisal

As only quantitative data were included from mixed methods studies, the appropriate quantitative section was completed. Similarly, for RCT studies, as only data reporting grief prevalence or associated factors were included, either the non-randomized quantitative study or quantitative descriptive study component of the MMAT was more appropriate to complete than the RCT component. For the purpose of this review, a high-quality study was determined by studies meeting four or five of the MMAT criteria. Of the six studies where the quantitative descriptive component of the MMAT was completed, five studies were rated high quality. No studies met the criteria related to the sample being representative of the target population. Of the 49 studies assessed using the non-randomized quantitative study component, 16 studies met all the criteria, 23 studies met four of the five criteria, and 10 met 3/5. Twenty-five studies did not meet the criteria regarding representativeness of sample, 4 studies did not use appropriate measures to assess grief, and 12 studies did not control for confounders. Two studies did not have complete data (Table 2).

Table 2. MMAT results

Q1. What is the prevalence of pre-death and prolonged/CG and when does it become a clinical disorder?

Pre-death grief: Four studies (Chan Wei Xin et al., Reference Chan Wei Xin, Yap, Wee and Liew2019; Liew and Yap, Reference Liew and Yap2018; Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005; Ott et al., Reference Ott, Sanders and Kelber2007) reported the prevalence of pre-death grief data; 10–18% of participants were reported to be at risk of high grief based on the MMCGI or MMCGI-SF cut-off criteria of scores being one standard deviation above the mean (Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002). One study reported 16.7% met the criteria for PGD as assessed using the PG-12 before death (Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015); Givens (2011) used 11 items of the PG-12 and reported a low rate of participants met the criteria for PGD. Moore et al. (Reference Moore2017) reported 38% had a high occurrence of symptoms as assessed by the ICG short-form pre-loss version. See Supplementary File 2 for detailed prevalence data.

Complicated grief: 20–26% of participants were reported to meet the criteria of CG as assessed by the 19 item ICG (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006; Nam, Reference Nam2015). Two studies used revised versions of the ICG; Moore et al. (Reference Moore2017) reported 22% met the criteria of CG using a 16 item version, and Romero et al. (Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) reported 6% of participants met the criteria using a 15 item version.

Prolonged grief: Givens et al. (Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011) reported a low rate or participants met the criteria for PGD as assessed using 11/12 item PG-12 (see Supplementary File 2)

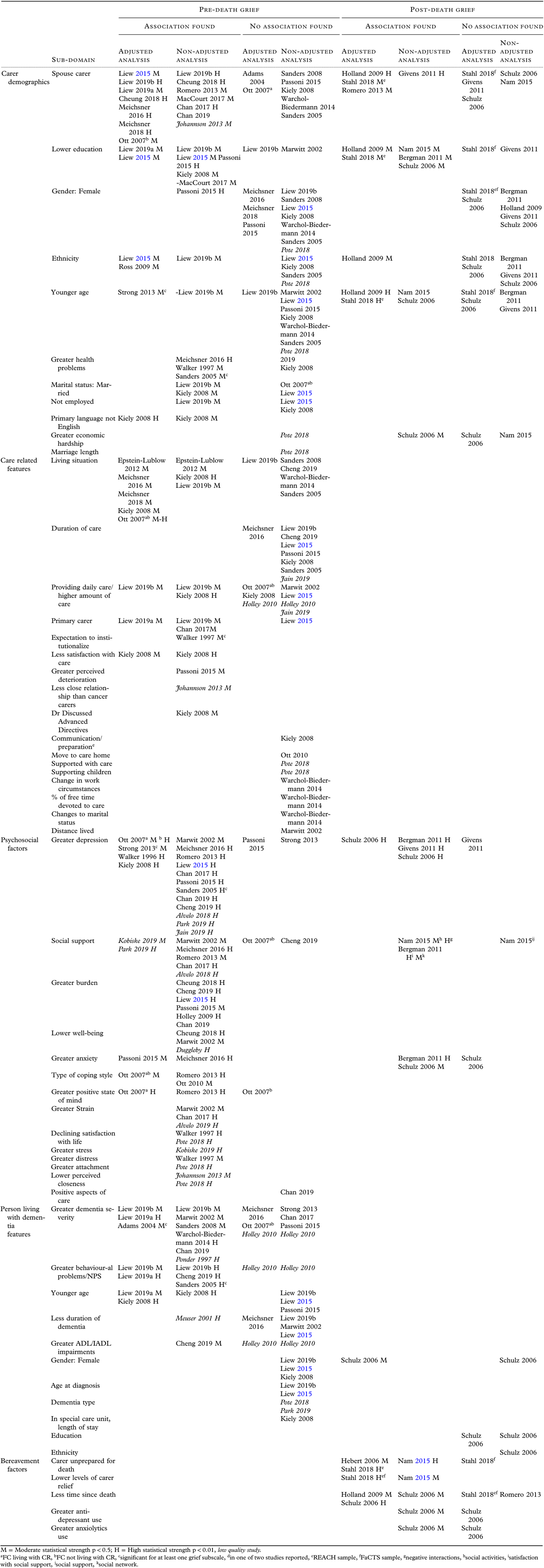

Q2. What factors associated with pre-death and prolonged/CG?

Pre-death and post-death associations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Q2 Associations with pre-death and post-death grief

M = Moderate statistical strength p < 0.5; H = High statistical strength p < 0.01, low quality study.

aFC living with CR, bFC not living with CR, csignificant for at least one grief subscale, din one of two studies reported, eREACH sample, fFaCTS sample, gnegative interactions, hsocial activities, isatisfaction with social support, jsocial support, ksocial network.

Pre-death associations (n = 31)

Carer demographic factors

Relationship type: The evidence indicates being a spousal carer is associated with higher pre-death grief than adult children or other relationship types with 10/16 studies reporting significant findings. Two studies found interaction effects: Cheung et al. (Reference Cheung, Ho, Cheung, Lam and Tse2018) found spouses caring for someone in later stages had the highest grief, and Ott et al. (Reference Ott, Sanders and Kelber2007) found being a spouse was only associated with higher grief when the carer did not live with the person living with dementia.

Lower education was found to be associated with higher grief in most of the studies which explored education (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019a; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008). However, one study (MacCourt et al. Reference Maccourt, Mclennan, Somers and Krawczyk2017) reported contradicting findings that not having a university education predicted lower grief and Marwit and Meuser (Reference Marwit and Meuser2002) found no association.

Gender was not found to be associated with grief (Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005; Warchol-Biedermann et al., Reference Warchol-Biedermann2014; Liew, Reference Liew2015; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Meichsner and Wilz, Reference Meichsner and Wilz2018; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Ott, Kelber and Noonan2008; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b) with the only significant association reported by Passoni et al. (Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015) who found being female was significantly associated with higher grief when gender was the only predictor.

Ethnicity: The included studies reported mixed evidence for the impact of ethnicity on grief. Ross and Dagley (Reference Ross and Dagley2009) in a US-based study found African-Americans reported higher grief than white carers. Similarly, two Singapore-based studies found being of Malay ethnicity was associated with higher grief than Chinese/Indian/Eurasian/other ethnicities (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b). However, two US studies with a majority of white sample found no association with ethnicity (Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008; Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005).

Age: Carer age was not independently associated with total grief scores, with only one study reporting an association between older carer age and grief when age was combined into a demographic variable with education and caring time (Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015).

Care-related features

Living situation: Evidence was mixed regarding living situation of the person living with dementia and grief. Caring for someone who was hospitalized (Epstein-Lubow et al., Reference Epstein-Lubow2012), living with the person before institutionalization (Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008), and currently living with the person (Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Meichsner and Wilz, Reference Meichsner and Wilz2018) were found to be associated with higher grief. Whereas no associations were found between grief and living with the person in two studies (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019; Warchol-Biedermann et al., Reference Warchol-Biedermann2014) or whether the person lived at home or in residential settings and grief (Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Ott, Kelber and Noonan2008).

Duration of care was not found to be associated with grief (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b; Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005; Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015).

Primary carer: Being the primary carer was mainly found to be associated with higher grief (Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019a; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wong, Kwok and Ho2017).

Amount of care provided: The studies report mixed evidence for an association between providing daily care or amount of time spent providing care and grief. Liew et al. (Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b) found providing daily care was associated with higher grief and Kiely et al. (Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008) found an association with providing a minimum of 7 hours of care a week. However, no association was found between perceived amount of care provided and grief (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002).

Carer health and psychosocial factors

Depression and burden: Greater depression (Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008; Walker and Pomeroy, Reference Walker and Pomeroy1996; Ott et al., Reference Ott, Sanders and Kelber2007; Strong and Mast, Reference Strong and Mast2013; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013; Liew, Reference Liew2015; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wong, Kwok and Ho2017; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Sanders and Adams, Reference Sanders and Adams2005; Chan Wei Xin et al., Reference Chan Wei Xin, Yap, Wee and Liew2019; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019) and higher levels of burden (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Ho, Cheung, Lam and Tse2018; Holley and Mast, Reference Holley and Mast2009; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Chan Wei Xin et al., Reference Chan Wei Xin, Yap, Wee and Liew2019) were associated with higher grief.

Coping styles: Dysfunctional coping was found to be positively associated with grief (Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013; Ott et al., Reference Ott, Kelber and Blaylock2010). Additionally, Ott et al. (Reference Ott, Sanders and Kelber2007) found greater use of coping by emotional venting was associated with grief when the person lived at home, and coping by planning and self-blame were positively associated with grief when the person did not.

Social support: Elements of social support appear to have a positive impact on grief. Negative associations were found between grief and perceived social support (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wong, Kwok and Ho2017; Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) and an association was found between greater satisfaction with social relationships and lower grief (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016). Support was reported to buffer the effect of grief and mediate the negative relationship between grief and psychological well-being in a study by Park et al. (Reference Park, Tolea, Arcay, Lopes and Galvin2019). Social network size was not found to be associated with grief (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019).

Carer health problems: The studies report mixed evidence as to whether greater health problems were associated with higher grief; two found significant positive associations (Walker and Pomeroy, Reference Walker and Pomeroy1997) and two reported no association (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019; Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008) while Sanders and Adams (Reference Sanders and Adams2005) reported an association for the MMCGI subscale HSL only.

Person living with dementia related factors

Dementia severity: Mixed findings were reported for the impact of dementia severity and grief. Eleven studies explored severity, and associations between greater dementia severity and higher grief were found in seven (Adams and Sanders, Reference Adams and Sanders2004; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019a; Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Ott, Kelber and Noonan2008; Warchol-Biedermann et al., Reference Warchol-Biedermann2014; Chan Wei Xin et al., Reference Chan Wei Xin, Yap, Wee and Liew2019). One study (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wong, Kwok and Ho2017) found dementia severity was only associated with grief for spouse carers and four studies found no association (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Ott et al., Reference Ott, Sanders and Kelber2007; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Strong and Mast, Reference Strong and Mast2013)

Behavioral problems/neuropsychiatric symptoms: There was some indication that behavioral problems or neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with higher grief; severe behavioral problems (Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019a; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b) and disruptive behaviors and psychotic symptoms (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Ma and Lam2019) were associated with higher grief.

Age of person living with dementia: Evidence was mixed regarding younger age of the person living with dementia and carer grief.

Duration of dementia was not found to be significantly associated with grief (Liew, Reference Liew2015; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b; Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016).

Gender of person living with dementia was also not associated with grief (Kiely et al., Reference Kiely, Prigerson and Mitchell2008; Liew, Reference Liew2015; Liew et al., Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019b).

Associations with CG/PGD (n = 6)

Carer demographic and care-related factors

There was no association between carer gender and CG. Less education was mainly found to be associated with higher CG. Ethnicity was explored in five studies, with the evidence suggesting no association with grief. There was mixed evidence regarding whether being a spouse carer was associated with higher CG than adult children or other relationship types.

Carer health and psychosocial factors post loss

Post-death social support: Surprisingly, Nam (Reference Nam2015) found participants with higher grief were more likely to participate in social activities and less likely to pursue negative interactions. Social support and satisfaction with support were not significant. Bergman et al. (Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011) found satisfaction with support was strongly negatively associated with grief, and having less people in their social network was moderately associated with higher grief.

Post-death depression: Higher post-loss depression was associated with higher CG in all studies (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011).

Bereavement factors

Mixed findings were reported regarding an association between time since death and grief. Schulz et al. (Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006) and Holland et al. (Reference Holland, Currier and Gallagher-Thompson2009) reported strong evidence that grief improved over time, while Stahl and Schulz (Reference Stahl and Schulz2018) and Romero et al. (Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) did not find associations. Retrospective reporting of being unprepared for the death (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Dang and Schulz2007; Nam, Reference Nam2015; Stahl and Schulz, Reference Stahl and Schulz2018) and lower levels of relief (Stahl and Schulz, Reference Stahl and Schulz2018; Nam, Reference Nam2015) were associated with higher grief.

Q3. In longitudinal studies, what is the relationship between pre-death factors and post-death prolonged/CG?

Associations from six longitudinal studies relating to this research question are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Q3 Associations between pre-death factors and post-death grief in longitudinal studies

M = Moderate statistical strength p < 0.5, H = High statistical strength p < 0.01.

aREACH sample, bFaCTS sample, cnegative interactions, dsatisfaction with support, esocial integration.

NH, nursing home; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Pre-loss carer factors

Two studies explored pre-death grief (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) and both report strong evidence of an association between high pre-death and high post-death grief even when accounting for confounders. Romero et al. (Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) reported 34% of post-death grief was accounted for by pre-death grief. The evidence indicates pre-loss depression is associated with CG post-death, with all studies finding associations between higher depression and higher grief (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Currier and Gallagher-Thompson2009; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006; Boerner et al., Reference Boerner, Schulz and Horowitz2004).

Of the three studies (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011; Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Dang and Schulz2007) which explored elements of religiosity, a significant negative association was only found between religious attendance and grief (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Dang and Schulz2007).

Two studies measured social support before and after the death. Romero et al. (Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) found no association between grief and social support. Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Dang and Schulz2007) found an increase in social integration from pre-loss to post-loss was associated with fewer grief symptoms. An increase in satisfaction with support pre- and post-death was not associated with grief.

Amount of care provided, believing the person had at least 6 months to live, and carer’s understanding of the complications of dementia were explored in one study, and no associations with grief were found (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011).

Pre-loss person living with dementia factors

Schulz et al. (Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006) found that younger age, greater dementia severity, and a higher dependence in activities of daily living (ADLs) were all significant independent predictors of higher grief. When demographic and bereavement confounders were controlled for, however, greater dementia severity and dependence in ADLs, and the person being female emerged as significant predictors of higher grief. However, Givens et al. (Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011) and Stahl and Schulz (Reference Stahl and Schulz2018) both found dementia severity was not associated with grief, with Givens et al. (Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011) reporting younger age, having lived with the person prior to nursing home admission, and the person having been hospitalized in the last 90 days of life to be associated with higher grief.

Q4. What services do carers use to manage grief?

Pre-death: Walker and Pomeroy (Reference Walker and Pomeroy1997) and Ott et al. (Reference Ott, Kelber and Blaylock2010) reported support group attendance (36% and 35%, respectively). Ott et al. (Reference Ott, Kelber and Blaylock2010) found nearly a third of participants used resources from dementia-related organization and 60% attended an adult care program. Loos and Bowd (Reference Loos and Bowd1997) reported perceived helpfulness of services; family assistance was the most helpful (60%), followed by physicians (57%), friends (43%), Alzheimer’s Society dementia charity (32%), support groups (22%), and nurses (22%). Kobiske et al. (Reference Kobiske, Bekhet, Garnier-Villarreal and Frenn2018) reported 56% of carers of someone living with young onset dementia had not received professional counseling.

Post-death: Bergman et al. (Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011) reported 30% accessed at least one service (i.e. counseling, support group or psychotropic medication), 13% received either individual, family, or pastoral counseling, and 13% accessed a bereavement support group. Crespo et al. (Reference Crespo, Piccini and Bernaldo-de-Quirós2013) found 98% accessed professional help and 84% received support from non-formal sources. While only 16% accessed bereavement services, 38% reported a need to attend a bereavement-related service.

Discussion

This review synthesizes quantitative data from an extensive and disparate body of international literature. We attempted to address four key research questions, however, the bulk of the evidence focused on determining associations with grief.

Q1. What is the prevalence of pre-death and prolonged/CG and when does it become a clinical disorder?

The most commonly used measure of grief was the MMCGI and MMCGI-SF. The majority of studies reported mean grief scores for the whole sample which does not indicate whether individual participants scored at risk of high grief. From the studies that did report individual risk, 10–18% scored above this normative cut-off score, which fits the statistics of the original study assessing grief using this measure (Marwit and Meuser, Reference Marwit and Meuser2002). This suggests that a subsample of carers may need support at this stage. This is also likely to be at a time where grief is not recognized by society or family and friends and can lead to complex grief situations and feelings of isolation (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Marwit, Meuser and Harrington2007).

An important finding is that, despite an abundance of research into dementia carer grief, we are unable to determine the prevalence of carers experiencing high pre-death grief. This is reflective of pre-death grief being a described concept without diagnostic criteria, and lack of a clinical tool to assess the experience. The MMCGI and MMCGI-SF allow comparisons with a normative sample score, which is statistically and not clinically driven. In the absence of a gold-standard screening tool, using this approach can identify carers who may be at risk of experiencing higher grief who are in need of further assessment, but may miss others in need of support but who score lower than the top 18%.

Indicators of disordered post-death grief are identified in the literature by the use of validated measures developed against a defined criteria; the ICG was most commonly used and determines indicators of pathological grief. The prevalence of CG ranged from 6 to 26% from four studies (although there is no validated cut-off score for the ICG-r). One study used a modified version of the PG-12 measure to assess PGD, and found a low rate of participants met the criteria. Subtle but key differences exist among the different criteria for PGD or CG and the algorithms applied to determine prevalence, and while PGD is a classified disorder in the ICD-11, there is not currently a validated tool which assesses all of the proposed criteria. Therefore, reported prevalence should be interpreted with caution and within the context of individual studies’ criteria and assessment of grief (Lenferink et al., Reference Lenferink, Boelen, Smid and Paap2019; Eisma et al., Reference Eisma, Rosner and Comtesse2020).

Q2. What factors are associated with pre-death and prolonged/CG?

Our findings build on the work of Chan 2013 and highlight that being a spouse carer, less educated, caring for somebody at a more severe stage of dementia, and higher levels of burden and depression are associated with greater pre-death grief. Studies exploring associations with post-death grief scores reported using the measures described above found that higher levels of pre-death grief and depression were predictive of higher post-death grief. Not being prepared for the death of the person and lower levels of carer education were also indicative of higher grief scores post-death. No studies conducted analysis to determine factors that were associated only with those who met the criteria for CG or PGD. There is mixed evidence for relationship type and post-death grief in comparison to pre-death grief, which may suggest that bereavement factors and other demographic or psychosocial variables have a stronger role post-death. Bereavement factors were less frequently explored in the reported studies, and it is unclear from the evidence whether time since death is associated with grief. Evidence for both pre-death and post-death grief suggests there is no relationship between carer gender and grief. Research in diverse samples is needed to further understand the relationship between ethnicity and grief.

There is, however, a difficulty of determining which factors are most associated with grief, which lies within the complexity and interplay of different variables. Evidence is limited to the factors included in studies and the type of analyses carried out. Variations in associations could be in part attributed to study methodology and study participants, particularly as 12 studies did not meet the MMAT criteria for attempting to account for confounders. For example, in contrast to much of the evidence, Passoni et al. (Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015) found relationship type had no direct impact on grief, and instead suggested the higher probability of spouses developing PGD can be attributed to sociodemographic or psychophysical features rather than being a spouse or adult child carer. Additionally, few studies explored how anxiety impacts on grief, but as evidence suggests carers do experience anxiety (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016; Passoni et al., Reference Passoni, Toraldo, Villa and Bottini2015; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Haley and Small2011; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang and Gitlin2006) often at the level of a clinical disorder (Moore et al., Reference Moore2017), future studies should be including it as a potentially influencing factor, particularly exploring direction of causality and the role of predisposing factors such as personality type.

The different measures used to assess grief and associated variables can also make it difficult to interpret or generalize findings. This is particularly relevant where different elements of a concept are explored under a shared term. For example, various aspects of social support were measured ranging from one question determining network size to a 20-item scale designed to measure the extent to which the individual perceives their needs for support, information, and feedback are fulfilled. It is therefore unsurprising that there is mixed evidence about the impact of social support. However, there is indication that elements of social support have a positive impact on grief, and exploring the role of social support domains and grief will increase our knowledge on how to support carers with grief. A recent study exploring grief in family carers in palliative care found that while there were no differences in pre-death or post-death grief in relation to social support, social support moderated the relationship between them. This was significantly stronger for those with lower social support, suggesting that those with high pre-death grief and low social support were more likely to have high post-death grief (Axelsson et al., Reference Axelsson, Alvariza, Holm and Årestedt2020).

Q3. In longitudinal studies, what is the relationship between pre-death factors and post-death prolonged/CG?

While only two studies (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer and Mitchell2011; Romero et al., Reference Romero, Ott and Kelber2013) explored the relationship between pre-death and post-death grief, they provide strong evidence that higher pre-death grief is associated with higher grief post-death. Higher pre-death depression was also associated with higher grief post-death. This highlights the importance of recognizing that carers may benefit from support with grief while they are still providing care. The need for grief support pre-death suggests that current grief and bereavement programs which target post-death grief may not be meeting the needs for this population. Further exploration of the role of social support and post-death grief is needed; Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Dang and Schulz2007) found an increase in social integration and having fewer negative social interactions were associated with lower post-death grief, while Nam (Reference Nam2015) found greater social activities were associated with higher grief. Nam (Reference Nam2015) interprets this finding within the context of the dual-process model, where social activities during bereavement may be indicative of a coping strategy.

Q4. What services do carers use to manage grief?

Due to the little evidence on service use in the included studies, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions to this question. Those that explored service use pre-death found that over a third of participants received counseling or attended a support group. An older study by Loos and Bowd (Reference Loos and Bowd1997) found participants reported support from family as being the most helpful. Typically, grief services are offered post-death, with pre-death grief being less frequently screened for by services. Therefore, increasing awareness and understanding of pre-death grief could be a promising step in being able to support those experiencing it. A recent study exploring the usefulness and acceptability of an animation to raise awareness of grief found some benefits of recognizing and identifying experiences as grief in carers of people living with dementia (Scher et al., Reference Scher, Crawley, Cooper, Sampson and Moore2021). Post-death service use was explored in just two studies where bereavement support groups and counseling were reported. Perhaps the most important finding was that self-reported need for bereavement services more than double the number of participants who used them (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Piccini and Bernaldo-de-Quirós2013). Service evaluations may provide further insight into what services are being provided, who utilizes services, and the effectiveness of them.

Strengths and limitations

We excluded non-English studies, qualitative studies and gray literature which may have meant we missed useful evidence. However, this study is able to provide an up-to-date reflection of what demographic and psychosocial factors are important to the experience of grief. While the included studies were conducted in a range of countries, studies from lower middle-income countries are underrepresented. However, research from different cultures is emerging, and differences in grief experiences being reported; relationship type was not found to be significant for Polish carers, and the authors suggest this is reflective of three-generational living and emotional ties between adult children and their parents remaining strong (Warchol-Biedermann et al., Reference Warchol-Biedermann2014). Similarly, Asian carers expressed more worry and felt isolation than the normative sample which was conducted in the USA (Liew, Reference Liew2015). There were also very few longitudinal studies that explored grief over time or into bereavement, which would provide a richer understanding of the grief experience. In some studies by the same authors, it was difficult to determine if the same samples were being reported so there may be some over-reporting factors associated with grief (e.g. Liew and Yap (Reference Liew and Yap2018) and Liew et al. (Reference Liew, Tai, Yap and Koh2019a). The included studies were of high quality as determined by the MMAT, with 44/55 studies meeting at least 4 of the 5 quality criteria. However, 25 studies did not meet the criteria related to samples being representative as most cohort studies recruited from dementia-related clinical or information services rather than general population samples.

Clinical and research implications

Tools such as the MMCGI may provide a useful screen to identify those at risk of high pre-grief, but awareness that certain demographic, psychosocial, and care recipient-related factors can influence the experience of grief will also be beneficial. While pre-death grief interventions are in their infancy, evidence from pilot studies indicates that interventions should be multifaceted and not increase carer burden due to the unique clinical presentation of pre-death grief in this population (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson2017).

While there is a huge body of research reporting cross-sectional data on the factors associated with grief, a shift is needed toward research building on the evidence from the few promising intervention studies undertaken (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson2017). For carers of people living with dementia living in care homes, a grief management intervention that involved group sessions with dementia education, communication skills, conflict management, and grief management skills demonstrated a reduction in the heartfelt sadness and longing subscale of the MMCGI (Paun et al., Reference Paun2015). Another intervention, aimed at carers caring for the person living at home, involved one to one counseling and reported promising grief-related benefits (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Kelber and Blaylock2010). Future research should continue to build on these findings to identify what individual components of grief interventions are most beneficial and who they are most beneficial for with regard to particular demographic and psychosocial factors. Utilizing standardized measures to assess grief and reporting those who are at risk of higher grief or who meet the criteria for Complicated or Prolonged Grief across the dementia caregiving trajectory will also further our understanding of who needs support and when.

Conclusion

This review builds on the previous findings of Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Livingston, Jones and Sampson2013) and synthesizes quantitative data exploring the grief experience of carers of people living with dementia. The findings indicate that particular demographic features and psychosocial characteristics play a role in grief for these family carers. Awareness of factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing higher levels of grief can help to identify those in need of support. Future research should consider the interplay of such factors and focus on potentially modifiable elements such as social support. There is limited evidence regarding service use and grief, and future research should also focus on what components of support or service provision are important for carers with regard to grief.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of authors’ roles

The review was designed and conducted by SC, KM, and NK. EW supported with the quality appraisal of studies, and ES contributed to the protocol. The manuscript was prepared by SC and critically reviewed and approved by all authors.

Acknowledgements

SC is part supported by Marie Curie, and NK is supported by Alzheimer’s Society Junior Fellowship grant funding, AS-JF-17b-016.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221002787