The title of William Yates’s 1838 treatise, Rights of Colored Men, aptly captures the subject of this book. The nineteenth-century Americans for whom Yates wrote were fascinated by a juridical puzzle: Not slaves nor aliens nor the equals of free white men, who were former slaves and their descendants before the law?

None were more interested in this question than black Americans themselves, and Birthright Citizens takes up their point of view to tell the history of race and rights in the antebellum United States. The pressures brought on by so-called black laws and colonization schemes, especially a radical strain, explain why free people of color feared their forced removal from the United States. In response, they claimed an unassailable belonging, one grounded in birthright citizenship. No legal text expressly provided for such, but their ideas anticipated the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment. Set in Baltimore, a place between North, South, and the Atlantic world, this book traces the scenes and the debates through which black Americans developed ideas about citizenship and claims to the rights that citizens enjoyed. Along the way they engaged with legislators, judges, and law’s everyday administrators. From the local courthouse to the chambers of high courts, the rights of colored men came to define citizenship for the nation as a whole.

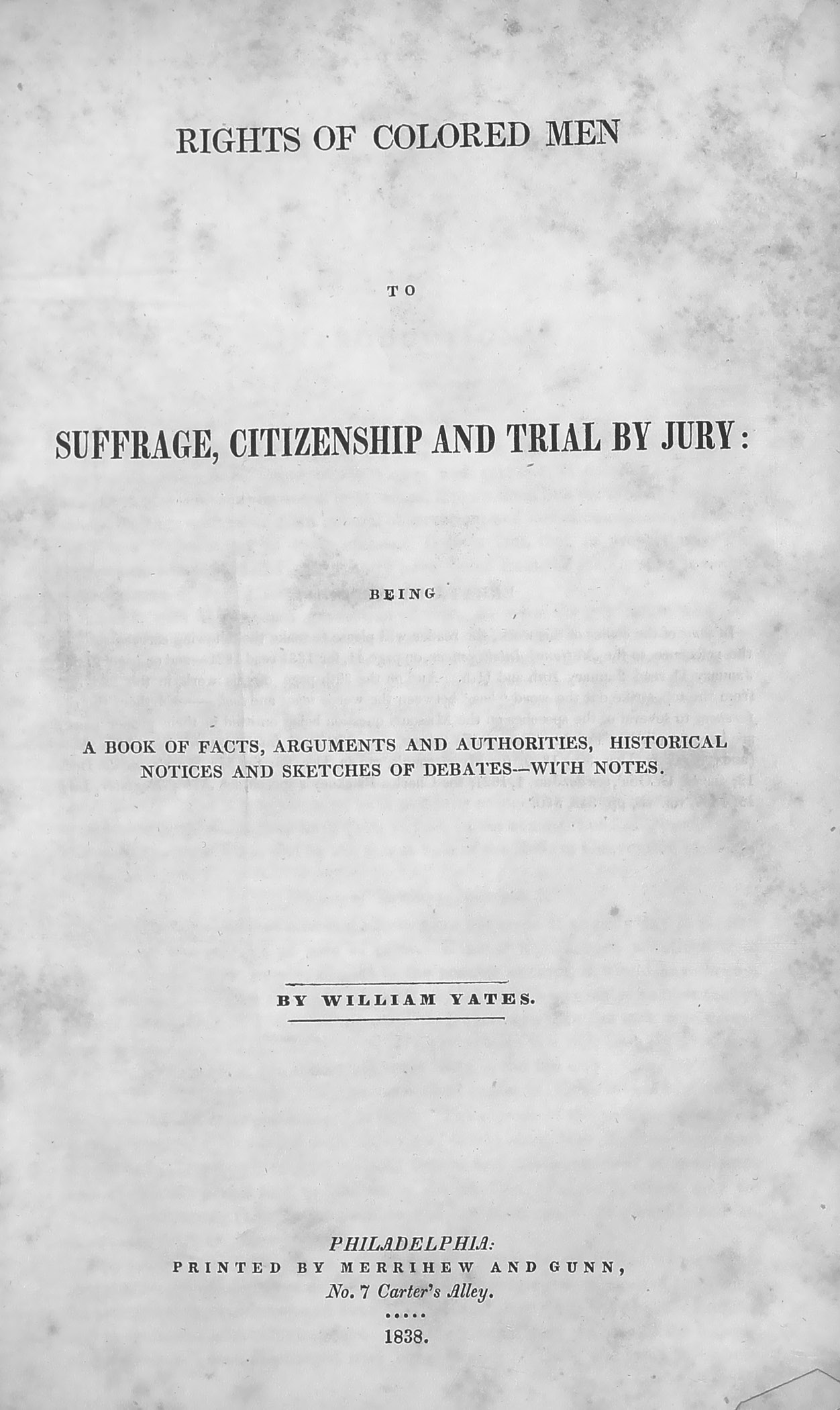

Yates authored the very first legal treatise on the rights of free black Americans.1 It was 1838 when Rights of Colored Men to Suffrage, Citizenship, and Trial by Jury was published in Philadelphia.2 He was not one of antebellum America’s highly regarded legal minds. Some say he read law for a time, although there is no evidence he was admitted to the bar. Instead, Yates’s career began with a short-lived stint as a newspaper publisher in his hometown of Troy, New York.3 His bona fides on the subject of race and citizenship were best established during his years as an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society.4 While many abolitionists maintained a self-conscious distance from free black communities, Yates centered his work there.5 The oppression of free people of color was a companion to slavery, in Yates’s view, with antislavery work necessarily extending into questions of free people’s status.6 Penning Rights of Colored Men was the pinnacle of this mission.

Figure I.1 William Yates, Rights of Colored Men. American Anti-Slavery Society agent William Yates made a case for the status of black Americans as citizens, consolidating arguments made in conventions, legislatures, and courtrooms. The result, Rights of Colored Men, was the first legal treatise on the subject. Image courtesy of the William L. Clements Library.

Yates placed a powerful instrument of authority in the hands of free African Americans and their allies. The antebellum legal treatise was a key tool in the standardization and dissemination of legal knowledge and was typically devoted to the comprehensive synthesis of a single branch of law.7 By the late 1830s, Yates was following on the success of James Kent’s Commentaries and Joseph Story’s treatise series.8 The genre had come to be associated with the concepts of law as scientific knowledge, legal education as systematic, and the profession as respectable.9 Yates successfully adopted legal culture’s own tool to such a degree that readers from the nineteenth century until today have regarded him as an authority on free black legal status. But Yates’s text was also a work of advocacy.10 Rights of Colored Men received prominent notices in the black and abolitionist press and could be purchased at local antislavery society offices.11 As a result, the work served as a probing legal treatise that fueled activist arguments.12

Yates provides a window onto the position that some activists – black and white – took on race and citizenship at the end of the 1830s. Law was an instrument of change, and Yates forthrightly explained his objective: to undermine prejudice against color. Racism had led to “legal disability”: exclusion from militia service, naturalization, suffrage, public schooling, ownership of real property, office holding, and courtroom testimony. Yates was especially unsettled by the disfranchisement of free black men in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and, more recently, Pennsylvania. Assembling evidence from legal culture, he believed, would help establish the rights and citizenship of free black people.13

Yates began with a story of the nation’s origins. The establishment of the United States, he said, had been at the outset a revolutionary, republican, and enlightened undertaking that was untainted by racism or distinctions among and between races. This had been possible in the wake of the American Revolution because the founding generation knew firsthand the contributions black people had made to independence, through military service and labor. American law had originally been color-blind, as evidenced by the absence of racial distinctions in founding documents, such as the federal and state constitutions.14

Change came in the early nineteenth century, at the fault line between generations. A forgetting occurred, Yates posited. Lawmakers of the early republic did not know how black people had contributed to the nation’s founding and hence were entitled to the privileges and immunities of citizens. In this sense, Yates’s aim was partly to restore that past to the nation’s political and legal memory. To achieve this, he compiled a history of lawmakers and their deliberations in which he found the development of antiblack prejudice in courts, constitutional conventions, and legislatures. He followed the professional lives of men whose work included roles from low-level administrator to convention delegate and judge. Their ideas about free black people moved with them.

Most powerful was Yates’s argument about how law, though suffering from amnesia, could be made right. The same instruments that had woven racism into the nation’s legal fabric – courts, conventions, and legislatures – could now be used to recraft it. Legal culture was also capable of reform, of itself and of the status of black Americans. With the restoration of revolutionary-era memories would come the reestablishment of racial equality. Lawmakers needed only to recall the past to restore racial justice, and Yates’s treatise aimed to be an agent of that remembering.15

Looking back, it is easy to conclude that Yates’s ideas were naïve. His faith in the power of historical knowledge, on the one hand, and the malleability of antiblack racism, on the other, seems like a misreading, given what we know of the rise of anti-free Negro thought and legislation in the 1840s and 1850s. But from Yates’s point of view in 1838, he had prominent lawmakers who were sympathetic to his view. He built his arguments on the published opinions of judges, legislators, and constitutional framers who also advocated that free black Americans had rights. Yates amplified their ideas, giving them visibility and volume, all the while hoping he might help convert others to an affirmative position on black citizenship.16

Yates made a bold claim: Free black Americans could not be removed – banished, excluded, or colonized – from the borders of the individual states or the United States. With this he confronted head on the thorniest legal question of the antebellum period: Were free African Americans citizens with a claim to place? His answer was yes. Citizenship, he wrote, was distinct from political rights. It “strikes deeper” than, for example, the right to vote.17 Denied the status of citizens, free black people were not secure in their “life, liberty, and property,” or what he termed “personal rights.”18 At its core, citizenship was a claim to place, to enter and remain within the nation’s borders. Citizenship, Yates believed, would protect free black people from expulsion.19

Yates adopted his most authoritative tone when discussing citizenship. The sections of his treatise on the vote and jury service leaned heavily on the published words of lawmakers. His discussion of citizenship was original, a structured synthesis that brought together a close reading of the Constitution with congressional debates and learned commentary. He began with four broad principles. First, no authority countered the view that free people of color were citizens, as contemplated by article 4, section 2, clause 1 of the Constitution. They were thus entitled to the “privileges and immunities of citizens.” Nothing in the common law of England, the principles of the British constitution, or the Declaration of Independence recognized a distinction of color. Second, public-law jurisprudence recognized two classifications of persons: citizens and aliens. All those born within a jurisdiction were citizens with an allegiance to the state that demanded both obedience and protection. Third, to be deprived of the vote did not mark one as a noncitizen; nonpropertied men, women, and children were citizens even though in some jurisdictions ineligible to vote. Fourth and finally, Yates rejected any analogy between the status of free black people and that of Indians or slaves. The legal position of Indians was murky, though largely, he thought, governed by treaty and related law. Slaves were property and categorically not citizens.20

Yates provided case studies. Congress’s 1820 debate over Missouri’s admission to the union had turned in part on whether the new state could bar free black people from entering the state without violating the United States Constitution’s guarantee of privileges and immunities. Then Major-General Andrew Jackson’s proclamations to the “free colored inhabitants of Louisiana” during the War of 1812 which implied that soldiers of color were citizens like their “white fellow-citizens.” In the example of Prudence Crandall, whose Connecticut school was said to have operated in violation of the state’s black laws by admitting children of color from outside the state, the citizenship of free persons of color had been a “turning hinge.” Crandall’s attorneys argued that such a distinction denied free black children, as citizens, their guaranteed privileges and immunities.21

Rights of Colored Men remained an influential text throughout the antebellum years.22 Other antislavery and African American activists would come to publish their own arguments about free black men and women as citizens. But few would adopt a form more cloaked in legal authority than that of the treatise. Yates’s text fueled understandings of the role that law might play in claims for free black rights. It was also an example of how formal lawmaking by white men was connected to the vernacular legal culture of free black communities. Yates made a record that suggests how close to agreement highly placed lawmakers and free African American activists could be in their thinking.23

Yates and his treatise were forgotten after the Civil War, as was the threat of removal that so concerned him. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 and then the Fourteenth Amendment made clear that those who were US-born were citizens, whether they were formerly free or formerly enslaved. Persons born in the United States were citizens of the United States and of the individual state in which they resided.24 The Civil Rights Act underscored that birthright was independent of “race, color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.”25 It was a momentous turn of events by every measure. Birthright citizenship, a principle that African Americans had long argued was embedded in the Constitution, was affirmed. Yates’s treatise survived but only in a literal sense, as a bound text tucked away on shelves that lined parlors and libraries.26

One century later, Yates and Rights of Colored Men were rediscovered. In the modern civil rights era, Yates’s treatise took on renewed relevance as the United States again confronted the dilemma of African American citizenship. Nineteenth-century ideas served as evidence of an origins story about how the black freedom struggle had begun in the decades before the Civil War. Historians of race and rights dusted off the past of early African American and antislavery activism. They found William Yates.

Charles Wesley was the first historian to recover Yates. Wesley was a prolific scholar, a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, and leader of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), known today the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History, or ASALH. Wesley was trained at Fisk and Yale, and received his PhD from Harvard in 1925. His scholarly energy was nearly boundless, and he published more than twenty books and many more articles, including survey-style works on black history. Wesley’s subject matter was sweeping, from labor to the Civil War, citizenship, and Reconstruction. Within the ASNLH, Wesley served as director of research and publications, president, and executive director.27

Wesley set out to document how black thinkers had forged a long tradition of historical writing. The occasion was the 1963 ASNLH presidential address. The practice, Wesley explained, had been “associated with the building of nationalism and group pride.” His starting point was comparative. Irish and Jewish people, like black Americans, had turned to historical writing to provide facts and combat oppression. Wesley’s “Creating and Maintaining an Historical Tradition” was a call to arms that urged ASNLH members to pursue historical scholarship and teaching with political commitment and insight. Wesley placed historical writing during the civil rights era on a continuum that dated back to the earliest decades of the nineteenth century. To write history in the 1960s was, for Wesley, to continue that critical work.28

Wesley turned to some of the first works by black historians to make his case. Their earliest efforts had not been academic, at least not by twentieth-century standards. Black history had been told, in Wesley’s view, before the publication of tracts and texts. African American orators were the first historians. Addresses delivered by men such as William Hamilton, Alexander Crummell, and Henry Highland Garnet “were evidence of the beginnings of the creation of an heroic tradition for Negro-Americans.” A written tradition by “Negro Americans” then emerged, with writers including Robert B. Lewis, author of Light and Truth (1836); James W. C. Pennington, author of the Text Book of the Origin and History of the Colored People (1841); William Cooper Nell, author of Services of Colored Americans, in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851); and William Wells Brown, author of The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863) at the fore.29 The first of these “Negro Historians” to be singled out by Wesley was William Yates, author of Rights of Colored Men. Yates had been a pioneering black historian.

Other historians also took notice of Yates, though they did not see him as Wesley had. John Myers included Yates in his study of American Anti-Slavery Society agents and their attention to the circumstances of free African Americans. Myers explained how the society had been generally ambivalent about working with free people in the North. However, by the mid-1830s a small cadre of agents was assigned that task, William Yates among them. Myers’s larger aim was to demonstrate this change in terms of antislavery activism.30

Yates was, Myers explained, “first secretary of the Troy Anti-Slavery Society,” representing that organization at national anniversaries in 1835 and 1836, and secretary and nominating committee member of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society. Myers documented how men such as Yates worked: They “gained the confidence of the colored people of Troy and were acceptable as agents to the Negro leaders of the country.” Myers did not directly address the matter of Yates’s racial identity, and assumed that he had been a white man who worked closely with black Americans.31

Had Yates been black or white? As other historians varyingly relied on Wesley and Myers, confusion resulted. In some cases, it appeared not to matter. Yates’s identity was no more than an embellishment. For example, when historian Harold Hancock published Yates’s “Letter of 1837,” a report about free black people in Delaware, he explained:

William Yates of Troy, New York, was a Negro minister who was one of two persons employed by the American Anti-Slavery Society in the fall of 1836 to assist Negroes in the larger towns east of the Appalachian Mountains. His headquarters were near New York City. In the middle of June 1837, he attended two conventions in Philadelphia and took the opportunity to visit a slave state, Delaware, for the first time. Most of his 18-month appointment was spent in gathering data for the Rights of Colored Men.32

Hancock appears to have read both Wesley and Myers and then developed a composite biography that wedded Wesley’s view of Yates as black with Myers’s explanation of his work as an antislavery agent. Could both be correct?

There was only one author of Rights of Colored Men, though the confusion is understandable. The evidence gleaned from early American Anti-Slavery Society reports supports Myers’s conclusion that Yates was a white abolitionist, a memorable one for his having worked with black people in the North.33 Indeed, the mix-up about Yates’s identity stems in part from his participation in black political and religious gatherings, and his faithful reportage on those meetings for the black press. Black commentators admired Yates and promoted his treatise.34 For example, when in October 1838 Yates attended a meeting of the New York Association for the Political Elevation and Improvement of the People of Color, he spoke from his book on “the legal disabilities of the colored man.” But Yates was not a delegate.35 Never in the writings of Yates does the pronoun usage shift – for example, from “them” and “theirs” to “us” and “ours” – in a way that would include Yates among black Americans.36 Wesley’s misapprehension of this unusual antislavery agent is understandable, but Myers was correct.

I was destined to return to Rights of Colored Men in researching this book. It is a singular text: the only nineteenth-century treatise devoted exclusively to the status of free African Americans. As I began my research, I dug deeper into Yates’s story and initially found little more than Myers had a half century earlier. Yates first appears in 1831, founding an upstate New York newspaper, the Troy Press.37 He was an antislavery agent in 1833 and can be found among the delegates to many local and national conventions.38 Yates conducted research for his treatise, visiting libraries and black communities between 1835 and 1837.39 With the publication of Rights of Colored Men, he became a familiar figure in African American religious and political gatherings.40 And then Yates receded from public life.41

Poring over newspapers, I came upon the unexpected. There was William Yates in the pages of the black-edited San Francisco Elevator. A review of William Wells Brown’s 1863 book, The Black Man, bore his name.42 This makes sense, I thought. Yates had migrated west and was still engaged with print culture and black politics. I read on, observing the review’s wide-ranging familiarity with African American political culture. Yates critiqued Brown for examining too narrow a slice of black leadership. There, I thought, was a reflection of Yates’s knowledge gained through years spent in free-black communities.

I continued my search with a working hypothesis in mind. Yates had migrated to California, as had many from the East after 1848. He had remained connected to black politics, and in that city he would have found many familiar figures – black activists who had settled in San Francisco and Sacramento from New York and Philadelphia.43 Yates had maintained an active interest in the rights of free black people and, in his characteristic way, was so deeply involved that he even wrote for the black press. It was a good hypothesis. But it could not have been more wrong.

My error was rooted in a simple fact. There had been two men named William Yates. The Yates who penned the Elevator review and the one who authored Rights of Colored Men were not one and the same. Still, their stories had parallels. Both had been involved in antebellum black politics and devoted their public lives to securing the rights of free people of color. Still, they could have not been more different. William Yates, the treatise writer, had been a gentleman of some means, enough to sustain himself as a volunteer for the antislavery movement. His institutional home had been the American Anti-Slavery Society, in which black men were marginalized in the 1830s. And he had been white.

William Yates the reviewer for the Elevator was born a slave and had an equally important story to tell about the history of race and rights. From Virginia, Yates purchased his freedom, migrated to Washington, DC, and began working as a porter at the United States Supreme Court.44 He had a legal education, the kind acquired through the negotiations that secured his liberty and through observing the goings-on in the nation’s high court. Yates understood the law of slavery and of freedom. His labors earned him enough to secure the manumission of his wife, Emeliner, and their three children.45 In the early 1850s Yates had moved to San Francisco, where he became a public figure.46

A columnist for the African American-owned news weekly the Elevator, writing under the pen name “Amigo,” Yates’s ideas circulated widely.47 Yates led California’s black political conventions as a man “possessed of great natural strength and ability” whose reputation was so widespread that “during the last days of a legislative debate, a state assemblyman would rise to support the right of black testimony by mentioning the name of William Yates as a man whose testimony would be as valid as any man’s.”48 The former slave made his mark on the very terrain that the treatise writer had once occupied: in newspapers and at black political conventions. He was also a man of action. Yates led a mid-1850s challenge against a state law that barred black testimony against the interests of white people. In 1865 he headed the black state convention’s committee on voting rights. His focus remained steadily fixed on the contours of black citizenship.

The discovery of a second William Yates is more than coincidence. It is an affirmation of the very premise of this book. Black Americans can serve as our guides through a history of race and rights. Never just objects of judicial, legislative, or antislavery thought, they are what drove lawmakers to refine their thinking about citizenship. On the necessity of debating birthright citizenship, black Americans forced the issue. Men like San Francisco’s William Yates wrote for newspapers, engaged in the vernacular study of law, debated in political conventions, and conducted themselves like rights-bearing individuals, all the while pressing for a radical redefinition of citizenship.

This study is indebted to happenstance and what I learned when the search for one William Yates led to the discovery of another. It was Yates the former slave who pointed me back to the free men and women of Baltimore, Maryland, where his ideas about race and rights went to the core of their struggles for belonging.

Legal historians have examined race and citizenship from three perspectives. Close reading of the antebellum era’s major treatises suggests that generally citizenship was not a major subject of legal commentary. To the degree the concept was relevant, it guaranteed few rights or privileges, with neither voting rights nor property ownership, for example, dependent on citizenship.49 When examining high court decisions, historians have relied on the 1857 case of Scott v. Sandford to explain the legal status of black Americans. This view defers to the opinion of Chief Justice Roger Taney, who held that no African American, enslaved or free, was a citizen of the United States.50 Still others have looked for the origins of African American citizenship in the era of Reconstruction, with the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment’s birthright citizenship provision. This view credits federal officials and Congress members with having devised and set in place the principle of jus soli in American law.51

Birthright Citizens confronts high court opinions and legislative edicts with the ideas of former slaves and their descendants.52 They too were students of law, though of a less orthodox sort, gleaning ideas from the world around them. Their ideas about the terms of national belonging were expressed in newspapers and political conventions.53 Their actions – petitioning, litigating, and actions in the streets – are a record of how people with limited access to legal authority won rights by acting like rights-bearing people. They secured citizenship by comporting themselves like citizens.54 They developed legal consciousness – an understanding of their lives through law – and sought badges of citizenship.55 This is not, however, a story of unbridled agency in a triumphalist sense.56 Inhabiting rights and comporting themselves like citizens only sometimes secured justice.57 Just as often, just ends remained elusive.

From shardlike courthouse records – dockets, minute books, and case files – this study pieces together the everyday ways in which African Americans approached rights and citizenship. Traces in the court archive do not speak for themselves, and rarely do they include narrative. To get these documents to speak requires building individual stories with particularity. The result is a history, told through a series of disruptive vignettes, that suggests how people without rights still exercised them. Quotidian courthouse appearances resonate with debates in legislatures, high courts, and political conventions. New characters in the history of race and rights – black Americans whose stories had long been buried in unopened leather books and case files tied up with red string – are linked to those of better-remembered figures – lawyers, judges, and legislators.

This approach is interesting for what it leaves out as well as for what it includes. Its grounding in the perspective of antebellum America’s black activists gives Birthright Citizens a selective and sometimes partial view of the era’s citizenship debate. A few dimensions of that debate, surely relevant to some lawmakers in the nineteenth century and of note for historians today, did not figure importantly in how African Americans understood citizenship. An important example is the federal circuit court decision of 1823 by Justice Bushrod Washington in Corfield v. Coryell.58 Washington’s explanation of the Constitution’s privileges and immunities clause is said to have influenced Reconstruction-era rethinking on citizenship. Today, legal scholars regard Corfield as an early and essential touchstone for arbitrating the rights of citizens. Still, there is no evidence that Corfield influenced the thinking about free African Americans in Baltimore or elsewhere. Later deemed influential, Corfield is outside the scope of this book.

This study also departs from those before it by looking for the history of law in debate and conflict, rather than in a positivistic interpretation of texts.59 Those who read Birthright Citizens looking for a new answer to an old question – Were black Americans citizens? – will find the answer is yes and no. Sometimes citizenship was defined in constitutions and statutes, although most of the time it was not. Courts disagreed and even changed their minds over who was a citizen and what rights might attach to that status. Commentators and treatise writers were never in accord and amended their writings to reflect changed thinking. The only consensus that emerges is one about the importance of fixing the status of free black people. Whether for or against designating them as citizens, there was widespread agreement about the need to situate former slaves in the nation’s legal regime. Beyond that, this is a story of how lawmakers and jurists fumbled, punted, confused, and otherwise failed to settle the question. Free black activists were generally of one mind. But even if they agreed that they were citizens, they did not agree about whether the state might affirm that fact. Faced with uncertainty, some fled for Northern cities, Liberia, or Canada. Many more stayed put.

Other studies have examined African American rights during the antebellum period, although few have expressly linked rights to citizenship as this book does.60 For the historian this is a thorny matter, foremost because not all antebellum Americans saw the relationship between rights and citizenship in the same way. For some, being a citizen was the gateway to rights. Citizenship was a prerequisite to the right to vote. For others, exercising rights was evidence of citizenship. If a person exercised the right to vote, it was evidence that he was a citizen. Often no relationship between rights and citizenship was articulated, leaving these as separate notions under law. Texts are of little help with this puzzle. In the absence of positive law – such as the later Civil Rights Act of 1866 – the equation linking rights and citizenship was never fixed. Black Americans’ efforts were aimed at securing rights that evidenced their citizenship. Still, when rights were denied them, free people of color inverted the argument: citizenship was said to be a gateway to rights.

“Rights” as used here refers to a process by which black Americans imagined, claimed, and enacted their relationship to law. Political theorist Bonnie Honig characterizes the assumption of rights and privileges by outsider subjects as a quintessentially democratic practice. Fundamental to democracy are the ways in which those said to be without rights make claims and “room for themselves.” Although Honig’s case is that of aliens, or noncitizens, her approach serves well a search for meaning in the rights claims of free people of color. Their rights making was messy, contested, and sometimes violent. How else, Honig asks, would those on the outside challenge the imbalance of power that framed such dynamics? Well before any judicial or legislative consensus granted their rights, free black men and women seized them, often in everyday claims that set them on a par with other rights-bearing persons.61 Only later did those rights become enshrined in text. In antebellum America, rights holders were those who did what rights holders did.62

This process of making rights was linked, for black Americans, to a broad claim to the “privileges and immunities of citizenship.” Rights, like citizenship, were not self-evident in antebellum America. What were the rights of citizens? One answer comes out of a study of high court doctrine. The Supreme Court before the Civil War, for example, was slowly developing a right to interstate travel.63 Another answer lies in the nascent terms of foundational texts. Can we say, for example, that there was a right to the free exercise of religion before Reynolds v. United States was decided in 1878?64 Another touchstone is the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the nation’s first articulation of civil rights: “To make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property.” These textual expressions of rights existed alongside a view of rights as secured through their performance. Free African Americans became rights holders when they managed to exercise those privileges that rights holders exercised. And often they did so in ways that local authorities were bound to respect and enforce. They traveled between the states, they gathered in religious assemblies, they sued and were sued, testified, and secured their persons and property before the law. Their routes to doing so were sometimes circuitous, and they would need to reestablish such rights over and again. Still, the rights they inhabited became the rights they held. Sometimes they even appeared to be like citizens.

Citizenship had a piecemeal quality in antebellum America, defined only as needed. Who was a citizen? White aliens could become naturalized citizens. But what of those who declared their intention to naturalize before state courts? Were they aliens, citizens, or persons somewhere in between? The president was required to be a “natural born” citizen. Did this imply that others might be citizens by virtue of birth as well? White women and children were said to be citizens, though most agreed that their rights should be determined as much by age or sex as by their status. Paupers, the infirm, the feeble, and the insane represented a litany of conditions that functioned to compromise access to rights for those otherwise deemed citizens. From time to time, free people of color even held in hand affirmations of their citizenship. Black sailors, patent holders, and passport bearers carried such documents.

Place matters for any telling of race and citizenship. Birthright Citizens is set in Baltimore, where the specifics of region, political economy, and jurisdiction were critical to how law was constructed at the intersection of formal edicts and lived experience. This study’s approach to the history of law reflects insights gained from the many social histories of free African Americans that center on city- or countywide communities.65 Legal historians have adopted a similar frame, one that is guided by jurisdiction as a manifestation of the local.66 The authority that a locally grounded study cedes in terms of breadth, it gains many times over in depth and complexity. To burrow into the dynamics of a local legal culture is to open a window onto how ordinary people interpreted law, the important role of legal administrators, and the perspectives of everyday litigants. Local legal culture is an essential dimension of this story.

Baltimore may vie with Philadelphia and New Orleans for supremacy when it comes to studying free people of color. But for a study of race and citizenship, no city better lends itself to understanding this fraught intersection. Baltimore was the nation’s third largest city, situated on what historians have termed the middle ground, between North and South.67 Maryland was a slaveholding state with southern and eastern regions that relied on bound labor for staple-crop production. Yet Baltimore was more strongly linked to regions to the north where grain production was in the hands of free labor. The city sat closer to Philadelphia than to Richmond. Critically for this study, Baltimore was home to the nation’s largest free black community: some 25,000 residents, who built a robust public culture. By the 1830s Baltimore was in the throes of what historian Steven Hahn suggests was a century-long process of abolition and emancipation in the United States.68 The city was a cosmopolitan port, influenced by the influx of mariners and the news they carried. At the same time, it was a locality grappling with the questions posed by the shift toward a postslavery society. The city’s legal culture was sophisticated, autonomous, and claimed the era’s most celebrated jurist, Roger Taney, as one of its own. In nearly all his years on the Supreme Court, Taney lived in Baltimore, hearing cases in the city’s federal court and presiding over bar proceedings. Taney knew Baltimore’s streets, alleys, and free African Americans. His decision in Dred Scott reflected the tensions that free African Americans generated in Baltimore.

Baltimore’s local courthouse was a main stage, the crucible in which many thousands of black Baltimoreans came to know something about race and law. It was the space in which free African Americans confronted the state.69 Through quotidian civil proceedings, they entered legal culture, learned its rules and rituals, and secured allies. There they confronted lawyers, judges, clerks, adversaries, and a curious public. Often their cases were said to be of little note. But on closer examination, as they filled the court’s dockets, black claimants pressed the question of their own status. Underlying their brief appearances were questions about fundamental rights and privileges. Often these were muted in the interest of expedient and efficient administration. Nevertheless, the halls of the Baltimore courthouse echoed with questions about African American citizenship.

Chapters 1 through 4 examine the development of legal consciousness among black Baltimoreans. Without access to formal training, activists nonetheless studied law. Their primers were African American and antislavery newspapers and their classrooms, lawyers’ offices, ships at sea, and political conventions. Their questions were about rights and citizenship. Neither slaves nor the equals of free white men, free people of color pondered how to combat African colonization schemes and black laws. Most urgent was a radical strain of colonization that surfaced in Maryland, one that threatened their forced removal. They used rights claims and birthright citizenship to counter their opponents. But as Baltimore became increasingly distanced from New York and Philadelphia, activists turned to local avenues of redress and discovered the courthouse.

Chapters 5 through 7 explore what happened when black Baltimoreans turned to the local courthouse. There, they carried themselves like rights-bearing citizens. Disputes over church property and leadership brought hundreds of the city’s black Baptists and Methodists into the local courthouse. Their gatherings were one manifestation of a right to public assembly, and ownership of church property led them to sue and be sued. These same men and women inverted the intention of the black laws. Oppressive permit and license requirements were opportunities to make lawyers and judges party to an exercise of the rights to travel and to own firearms. As participants in the city’s associational economy, free people of color were woven into networks of debt and credit, and when they failed financially, petitions for insolvency were a route to extinguishing their obligations. The same proceedings stretched the limits of their rights: black men testified against the interests of whites and served as court-appointed trustees, roles that custom suggested they should not occupy. Families and friends sought court intervention to protect the interest of young apprentices. Family autonomy was at stake, and the writ of habeas corpus proved to be a powerful tool for bringing white indenture holders before a judge. Often the results were not what petitioners aimed for, but they filed claims, served as witnesses, and subjected to the rule of law schemes that threatened to operate much like enslavement.

Chapter 8 examines the era of Scott v. Sandford. Rather than a starting place, that notorious case was but a late volley in the antebellum story of race and rights. In Baltimore, the case was in one sense much anticipated, with local legal greats like Roger Taney and Reverdy Johnson playing important roles. Even as newspapers promoted the decision’s significance, underscoring the holding that no black person was a citizen of the United States, nothing changed in Baltimore. Black residents continued to exercise rights and conduct themselves like citizens in the state court venues that had long been the primary arbiters of such questions. State lawmakers continued to promote the forced removal of free African Americans – but their schemes failed. When Maryland’s high court had the opportunity to adopt the reasoning of Dred Scott, it declined and instead affirmed that free people of color had the right to protect their persons and property before the law. In the state capitol, a legislative push proposed reenslavement or expulsion as a remedy for the “free negro problem.” It too failed after black men and women from Baltimore lobbied for its defeat.

Birthright Citizens concludes with a look at the early years of Reconstruction. For readers familiar with this later period, much of what precedes it will seem similar. Indeed, between 1820 and 1860, black Baltimoreans confronted the very questions that would take center stage during Reconstruction. Were they citizens, and if so, what rights flowed therefrom? As the Civil Rights Act of 1866 put it, “All persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” The claim to birthright citizenship was affirmed with a guarantee of civil rights. Free men and women of color likely recognized the claims they had already long been pressing. And they did not wait for Congress before seizing the opportunities presented by the new, postwar climate. They moved about, reuniting their families, they organized armed militias, and they lobbied for desegregated public schools. In the courthouse, they returned to challenge apprenticeship contracts and won the declaration that they were unconstitutional.

No work of history is a blueprint for the present, and too much has changed between the nineteenth and the twenty-first centuries to permit us to prescribe remedies for today based on lessons from the past. Still, the case of free people of color and their struggle for belonging will read to some as a cautionary tale. And Birthright Citizens is guided by questions that are resonant in our present day. How, we might ask now, as Americans asked 200 years ago, should we regard those among us whose formal relationship to rights and citizenship remains unsettled and a recurring subject of political debate? What cost is there to be paid by a nation that permits people to work, create families, and build communities within its geopolitical borders, but then declines to extend them membership in the body politic? Even as we attempt to contain these questions by way of piecemeal legal texts, why are we surprised that individuals and their communities will reach for the brass ring of citizenship in a society that metes out rights and privileges by way of that construct? Free black Americans and their nineteenth-century trials make clear the pitfalls of the country’s incapacity to sustain deliberations and arrive at resolutions. On the eve of the Civil War, nearly half a million people, the majority of them born in the United States, lived with their rights always subject to political whim and their belonging always subject to the threat of removal. We might say that they were not unlike today’s unauthorized immigrants and their children, at least to the degree that free people of color then were also a community that lived through episodes of punitive legislation and efforts to force their exile. Birthright Citizens is their story.