Introduction

ENT problems are extremely common in general practice, accounting for around 50 per cent of paediatric and 10 per cent of adult consultations.Reference Donnelly, Quraishi and McShane1,Reference Griffiths2 This is not, however, reflected in the proportion of time allocated to training in ENT at both undergraduate and post-graduate levels. In fact, ENT has been removed from the curriculum altogether in 9 out of the 29 medical schools in the UK.Reference Sharma, Machen, Clarke and Howard3 Undergraduate ENT training has been repeatedly found to be insufficient,Reference Ferguson, Bacila and Swamy4–Reference Mace and Narula7 and there is a substantial evidence base suggesting that many medical students and junior doctors lack basic ENT knowledge and skills.Reference Powell, Cooles, Carrie and Paleri5,Reference Khan and Saeed6,Reference Chawdhary, Ho and Minhas8–Reference Veitch, Lewis and Gibbin10

Amongst general practitioners, there is significant variation in exposure and training in ENT.Reference Clamp, Gunasekaran, Pothier and Saunders9,Reference Acharya, Haywood, Kokkinos, Raithatha, Francis and Sharma11 This has direct repercussions for the quality of care provided to patients, but also important implications for resource utilisation. For example, referral rates to ENT services are higher amongst general practitioners with less training in ENT.Reference Bhalla, Unwin, Jones and Lesser12

The UK has the lowest ratio of ENT specialists to inhabitants (1:103 000), falling behind countries such as Bulgaria (1:14 000) and Poland (1:25 000).13 Outside of the EU, the UK is out-performed by Canada (1:50 000), the USA (1:25 000) and Russia (1:28 000). The capacity to manage ENT conditions in secondary care is under significant strain. It is therefore important that ENT training, starting at medical school, is sufficient to equip qualifying doctors with core skills and knowledge in ENT.

ENT must, however, compete with an increasingly expanding number of other specialties in the undergraduate curriculum.Reference Lumley14 One solution to this dilemma has been to define core knowledge and skills for each specialty and deliver teaching within affiliated specialties. In the case of ENT, it has been proposed that core clinical skills could be delivered within allied specialties where ENT problems are frequently encountered, such as paediatrics, emergency medicine and general practice.Reference Sharma, Machen, Clarke and Howard3 Hospital-based ENT could still have a place in the curriculum, but as a special selected module for students with a particular interest in the field.

This paper aimed to assess the exposure of general practitioners working in England to ENT, both at undergraduate and post-graduate levels, and determine their satisfaction with this training. We also wanted to assess whether general practitioners thought undergraduate ENT should be taught outside of traditional ENT-based hospital firms.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

Participation in this questionnaire was voluntary and responses were anonymised. No specific ethical approval was sought.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was performed. A questionnaire compromising 22 questions was designed (by authors LD, HS and CR). The questionnaire was piloted at a general practitioner ENT training day held at Charing Cross Hospital in November 2017, where the questionnaire design, wording and contents were assessed. The final questionnaire was decided upon following the feedback from the pilot and by general consensus amongst all authors.

The questionnaire was divided into four broad sections: undergraduate exposure to ENT, post-graduate exposure to ENT, proposed changes to the medical undergraduate curriculum and ENT workload estimation in general practice (Appendix 1). The results from the latter section are part of a separate piece of work and are therefore not presented here.

Setting

The questionnaire was emailed to general practices in England. The study was conducted between June 2018 and January 2019. The questionnaire was initially distributed via e-mail to those general practices in England with listed email addresses on the National Health Service UK Service Directory for Clinical Commissioning Groups website. The distribution was broadened to include those general practices without e-mail address listings on the aforementioned website but which had the means to receive e-mails via their practice website.

Participants

The population of interest was general practitioners working in England. No level of training was pre-specified; therefore, this questionnaire was open to all grades, from foundation year 2 doctors working in general practice through to post Certificate of Completion of Training general practitioners.

Data sources and measurements

The questionnaire had a mixture of open and closed questions, the latter of which had a multiple-choice question or Likert scale format. There were optional text boxes for further comments. In addition, the year and place of medical qualification were obtained from all participants.

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using questionnaire software (Survey Monkey) and SPSS statistical software. Independent statistical advice was sought from the Statistical Advisory Service at Imperial College London. The research questions were primarily categorical in nature, which is represented in the descriptive analysis. Post-hoc analysis using Fisher's exact test was performed to assess whether certain factors were associated with respondents’ beliefs that ENT should remain in the undergraduate curriculum and their desire for further post-graduate teaching.

Results

A total of 2926 general practices were emailed, with 417 general practitioners responding to the questionnaire. It is not possible to calculate an exact response rate because individual general practitioners were not contacted.

The majority of respondents underwent training in the UK (89 per cent) (Figure 1). Primary medical qualifications were awarded between 1977 and 2017, with participants graduating from medical school on average 19 years ago.

Fig. 1. Bar chart showing location where primary medical qualification was awarded.

Undergraduate exposure

Sixty-seven per cent of respondents had a clinical ENT rotation at medical school and 52 per cent received a lecture-based programme. Of those with a clinical rotation, modal duration was two weeks. The majority of those who had received clinical rotations in ENT found clinics to be the most useful activity (81 per cent), followed by ward-based work, with time in operating theatres considered useful by the lowest proportion of respondents (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Bar chart showing activities considered most useful during undergraduate ENT rotation. N/A = not applicable

The average weighted mean score for usefulness of the undergraduate rotation was 3.2 out of 5 (where 5 represents extremely useful and 1 reflects not useful at all). The lecture programme was perceived overall as slightly more useful, with an average weighted score of 3.4 out of 5. Overall, participants were broadly dissatisfied with their undergraduate ENT education, with an average weighted score of 2.6 out of 5.

Post-graduate exposure

Only 27 per cent of the respondents had completed a rotation in ENT after graduating from medical school. Placements were most commonly undertaken as part of general practitioner training or for senior house officer jobs in ENT (Figure 3). Seventy per cent of respondents found this rotation extremely useful. Fifty-one per cent of respondents had received some form of post-graduate teaching in ENT (Figure 4), usually lecture-based.

Fig. 3. Pie chart showing stage at which ENT rotation was completed after graduation from medical school. GP = general practitioner

Fig. 4. Bar chart showing proportion of general practitioners who received post-graduate teaching in ENT.

The average weighted usefulness score of teaching was 4.13 out of 5. Nearly three in four respondents (74 per cent) wanted more post-graduate teaching. This proportion was significantly greater (80 per cent) for general practitioners who had not had a post-graduate ENT placement, compared to those who had undertaken a post-graduate ENT placement (57 per cent) (p < 0.00001, Fisher's exact test). However, there was no difference in desire for further post-graduate teaching between general practitioners based on whether they had completed undergraduate ENT placements (71 per cent vs 80 per cent) (p = 0.063, Fisher's exact test).

Undergraduate hospital-based ENT

Eighty-five per cent of participants believed an ENT hospital-based rotation should remain in the undergraduate curriculum. However, when asked if ENT core skills could be taught across other specialties, 55 per cent agreed with this. There was no relationship found between doctors’ completion of undergraduate or post-graduate ENT placements and their support for ENT hospital placements remaining in the undergraduate curriculum (p = 1.0, Fisher's exact test).

Qualitative analysis

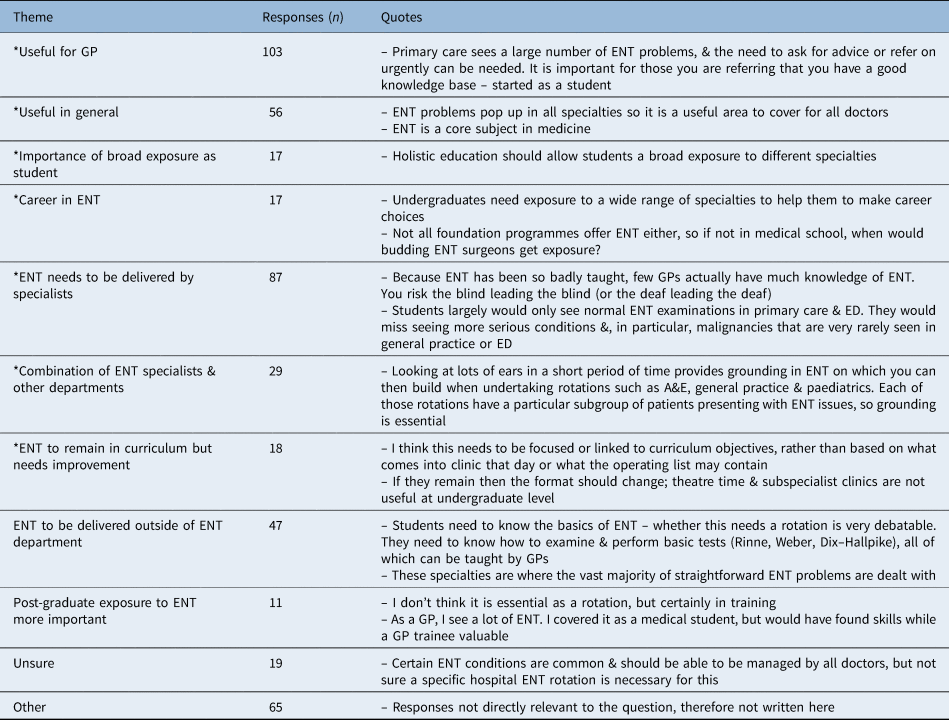

Qualitative analysis was performed on the comments made by the respondents to justify their answers. Responses were categorised into 11 themes; some example comments are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Quotes from respondents divided into 11 themes in response to whether hospital ENT should remain in undergraduate curriculum

*The responses shown for these themes are considered to be in favour of ENT remaining a separate hospital-based rotation. GP = general practitioner; ED = emergency department; A&E = accident and emergency

Discussion

This study found that general practitioners practising in England were generally dissatisfied with their training in ENT, both as medical students and as graduates. Approximately two in three respondents received an ENT rotation at medical school, and just over 50 per cent had a lecture-based programme. By contrast, the vast majority of those who completed the questionnaire had no post-graduate rotation in ENT.

• ENT problems are extremely common in primary care

• The need for adequate training in ENT is urgent; the UK has low provisions of ENT specialists per population in Europe

• The majority of general practitioners in England are dissatisfied with their undergraduate and post-graduate exposure to ENT

• Proposals to outsource ENT undergraduate training to affiliated specialties such as general practice are of concern

Our results are in keeping with the only other study in England that investigated exposure to ENT amongst general practitioners, performed over a decade ago.Reference Clamp, Gunasekaran, Pothier and Saunders9 Similar findings have also been found in Ireland.Reference Lennon, O'Donovan, O'Donoghue and Fenton15 Clamp et al. (2007) reported that most general practitioners had completed an undergraduate rotation in ENT, but only a quarter had a post-graduate rotation.Reference Clamp, Gunasekaran, Pothier and Saunders9 That study also found that three in four general practitioners would like additional post-graduate training.Reference Clamp, Gunasekaran, Pothier and Saunders9 Lack of improvement in these areas over the time frame is of clinical concern and highlights unaddressed curriculum gaps in training.

ENT disorders comprise a significant proportion of the workload in primary care.Reference Donnelly, Quraishi and McShane1 It is therefore imperative that general practitioners are confident and competent in managing common issues, and know when to refer to secondary care.Reference Oosthuizen, McShane, Kinsella and Conlon16 Given the Department of Health's target for 50 per cent of medical students to become general practitioners,13 a greater provision of ENT training is crucially needed at medical school. Evidence suggests that the majority of medical school graduates and junior doctors do not feel adequately prepared to practise ENT.Reference Ferguson, Bacila and Swamy4 Furthermore, the provision of ENT services is falling short of the levels needed to meet current requirements. In 2009, 20 per cent of the 3.3 million out-patient appointment attendances in Ireland were for ENT services.Reference Oosthuizen, McShane, Kinsella and Conlon16 With reduced access and longer waiting times for specialist ENT services, more ENT care will inevitably fall to general practitioners.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively assess general practitioners’ opinions regarding the delivery of undergraduate ENT training. While the overwhelming number of general practitioners who responded believe that hospital-based ENT firms should remain within the undergraduate medical curriculum, over half felt that core ENT skills could be taught across affiliated specialties.

Qualitative analysis of answers to the open questions revealed a number of key areas. In favour of maintaining ENT placements within the curriculum were suggestions that ENT is best taught by those within the specialty. The pathologies seen in hospital are different to those observed in primary care, including acute presentations, and general practitioners may lack the knowledge and relevant clinical skills to be the primary instructors. In addition, many respondents highlighted the inherent importance of keeping medical students’ exposure broad, and feared the potential detrimental effect of removing ENT firms for future career choices in this specialty. Some respondents also raised the issue of having the capacity to cover specialty teaching within primary care.

A proportion of responses were in favour of maintaining ENT training delivered by ENT departments, but highlighted the need for improving the quality of the training. There was particular emphasis on the targeted learning of core skills and knowledge, rather than specialist areas with limited application such as complex surgical procedures.

Those who were in favour of abandoning ENT hospital-based undergraduate rotations commonly cited reasons including the high frequency of ENT-related problems in other specialties and the perceived limited benefit of hospital-level ENT exposure.

Although there exists competition from other specialties, this study has demonstrated that there is still a place for an ENT-based undergraduate rotation. For this to be maximally useful, however, a more structured skill and core knowledge based curriculum is required, rather than opportunistic apprentice models where the quality of learning can be highly variable.Reference Rassie17 The General Medical Council highlights the need for medical schools, in partnership with local education providers, to ensure that clinical placements offer the learning opportunities needed to meet the required learning outcomes.18 This can be challenging, particularly for already stretched frontline staff with service-provision demands, and can impact on the quality of the teaching if those delivering the teaching are not trained. One solution to this problem, found to be popular with students, is to hire dedicated teaching fellows to co-ordinate medical student placements.Reference Woodfield and O'Sullivan19

Affiliated specialties, such as general practice, accident and emergency, and paediatrics, which encounter a considerable ENT workload, can be used to deliver ENT training. Indeed, this proposal was supported by a large proportion of general practitioners surveyed. However, the recommendation here is that these departments offer the means to reinforce knowledge, rather than supersede ENT placements.

Another point highlighted by the questionnaire responses is that post-graduate training, particularly ENT rotations at senior house officer level, but also other more limited clinical attachments, are highly valued by general practitioners. Typically, foundation trainees rotate across six specialties over two years, and, similarly, general practitioner trainees rotate across three to five hospital placements. Hence, providing all general practitioner trainees with a rotation in ENT may not be feasible, given competition from other specialties and regionally organised training rotations. However, there is evidence that a single focused and dedicated ENT teaching session can improve confidence and knowledge amongst general practitioner trainees.Reference Acharya, Haywood, Kokkinos, Raithatha, Francis and Sharma11 Indeed, the results presented here demonstrate that the demand for post-graduate training is higher amongst general practitioners with no history of post-graduate rotations in ENT.

Strengths and limitations

Over 400 responses were collected; thus, the findings are based on a large sample of general practitioners. The responses were also anonymised and the questionnaire did not require the provision of additional demographic details, which may have encouraged participation and completion. In addition, the collection of qualitative data allows a valuable insight into the current opinions of general practitioners regarding the provision of training in ENT. The questionnaire was distributed amongst all general practices with accessible e-mail communication in England, and therefore is not restricted to a particular geographical region.

There were, however, a number of limitations to this study. For instance, the questionnaire was optional and therefore subject to selection bias. There may also be recall bias, as the questionnaire required memory of previous ENT exposure. The respondents who completed the questionnaire graduated on average almost 20 years ago. Their viewpoints and experiences may therefore not be representative of ENT training today. In addition, the questionnaire was restricted to England and the findings may not be applicable beyond this area.

Conclusion

As things stand, currently practising general practitioners in England report dissatisfaction with ENT training, both before and after medical qualification. This is of significant concern given the high ENT workload amongst this group of doctors. It also raises doubts as to the suitability of deferring ENT education at medical school to affiliated departments such as general practice. The overwhelming majority of respondents felt that specialists are best equipped to deliver teaching, particularly given the self-reported lack of confidence amongst general practitioners in managing ENT problems.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Statistical Advisory Service at Imperial College London.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Questionnaire concerning ENT undergraduate and post-graduate training amongst general practitioners

Undergraduate ENT rotation

1. Which medical school did you go to?*

2. What year did you graduate?*

3. Did you have an ENT rotation at medical school?* Yes No

4. How long was the rotation?

5. What activities did you engage in on the rotation?

Clinics Ward-based Theatre Not applicable

6. Which of these did you find most useful?

Clinics Ward-based Theatre Not applicable

7. How useful was the rotation overall?

Undergraduate ENT lecture programme

8. Did you have an ENT lecture programme at medical school?*

Yes No Unsure

9. How long did it last for?

10. How useful was the lecture programme overall?

11. How satisfied were you with your training in ENT as a medical student?*

12. Do you think an ENT hospital-based rotation should remain in the undergraduate curriculum?*

Yes No Unsure

Please give your reasons:

13. Do you think core ENT knowledge and skills should be taught in other rotations (e.g. A&E, GP, paediatrics) and hospital-based ENT rotations limited to self-selected modules for students with an interest in ENT?*

Yes No Unsure

Please give your reasons:

Post-graduate rotation in ENT

14. Have you completed a hospital post in ENT after leaving medical school?* Yes No

15. What level of training was this?

F1 F2 GPST1–3 Not applicable

Other (please specify):

16. How useful was this?

Post-graduate teaching in ENT

17. Have you received post-graduate teaching in ENT?* Yes No

18. What sort of teaching?

Course Lecture Hospital teaching session(s) Not applicable

Other (please specify):

19. How useful was this teaching?

20. Would you like more post-graduate training in ENT?* Yes No

ENT in general practice

21. From your experience, what percentage of paediatric GP attendances are ENT-related?*

22. From your experience, what percentage of adult GP attendances are ENT-related?*

*Indicates main question with required answer; questions without an asterisk are related follow-up questions for which a response may not be needed (i.e. if did not answer positively to the main question).