11.1 Introduction

Global climate governance has undergone a ‘Cambrian explosion’ of organisations, norms, ‘contributions’, commitments and other institutions (Keohane and Victor, Reference Keohane and Victor2011; Abbott, Reference Abbott2012). The result is an intricate, diverse institutional complex that exhibits the defining features of polycentric governance (see Chapter 1). Multiple centres of decision-making authority adopt rules, standards and policies and conduct other governance activities; these authorities act at multiple scales, from international to local (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a; Cole, Reference Cole2011, Reference Cole2015).

Recent trends have increased polycentricity: climate institutions have become more numerous and diverse. Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement allow for diverse national commitments; subnational governments have expanded their commitments and actions, domestically and transnationally; and a new voluntary commitment system (VCS) has encouraged domestic and transnational initiatives by non-state actors (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017). As polycentric governance theory suggests, these developments should increase the resilience of climate governance; for example, as the Trump administration weakens US support for intergovernmental action, private and subnational actions may provide partial substitutes.

Polycentric governance has costs as well as benefits (Keohane and Victor, Reference Keohane and Victor2011; Abbott, Reference Abbott2012; van Asselt and Zelli, Reference van Asselt and Zelli2014; see also Chapter 1). Many scholars therefore conclude that polycentric structures operate more effectively with modest levels of coordination or ordering (Zürn, Reference Zürn and Levi-Faur2010; Betsill et al., Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015; Mayntz, Reference Mayntz2015; Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017). This chapter focuses on orchestration, an important approach to institutional ordering widely applied in climate governance.

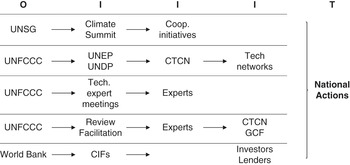

Orchestration is an indirect mode of governance that relies on inducements and incentives rather than mandatory controls (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015). It is common in many areas of global governance, where ‘governors’ – from intergovernmental organisations (IGOs) to transnational initiatives – possess limited authority and power for binding, direct action. But even powerful governors, including states, engage in orchestration. An orchestrator (O) works through like-minded intermediaries (I), catalysing their formation, encouraging and assisting them and steering their activities through support and other incentives, to govern targets (T) in line with the orchestrator’s goals (O-I-T). An orchestrator can also structure and coordinate intermediaries’ activities to enhance ordering (Abbott and Hale, Reference Abbott and Hale2014; Abbott, Reference Abbott2017).

The prevalence of orchestration has significant implications for several of the core propositions of polycentric governance theory outlined in Chapter 1. I consider three such propositions here:

(1) Local action: that organisations constituting polycentric systems emerge spontaneously at local levels amongst self-organising actors, perhaps facilitated by organisational entrepreneurs (Andonova, Reference Andonova2017; see also Chapter 7), but without higher-level intervention. In climate governance, by contrast, states, IGOs and other actors have actively catalysed and facilitated the formation of many new organisations.

(2) That organisations within polycentric systems spontaneously coordinate their actions through mutual adjustment, without centralised intervention. In climate governance, by contrast, while many organisations undoubtedly adjust to one another’s actions, states and IGOs have orchestrated extensively to structure the complex, although they have not strongly coordinated organisational behaviour.

(3) That polycentric systems promote experimentation, policy innovation and learning (see Chapter 6). Polycentricity (and orchestration) have stimulated climate experimentation in a broad sense by encouraging diverse organisations and actions (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011). Yet the pursuit of other governance goals limits experimentation in some domains. In addition, without an organised system to manage experiments and evaluate their results, climate experimentation and learning fail to reach their full potential (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017).

This chapter first maps the climate governance complex, identifying orchestrators, intermediaries and targets. It then contrasts theoretical perspectives that emphasise spontaneous, decentralised coordination, including polycentric governance theory, with more strategic approaches, including orchestration. It reviews actions across many areas of climate governance, demonstrating the importance of orchestration. It then considers the findings of the analysis, returning to the three propositions identified earlier. This chapter closes by suggesting areas, including experimentation, where further orchestration may be desirable.

11.2 Orchestrators, Intermediaries and Targets in Climate Governance

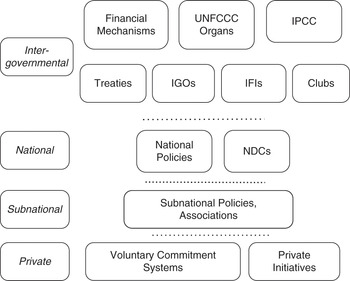

Global climate governance consists of multiple types and systems of organisations. Figure 11.1 depicts the principal organisations and groupings, highlighting different scales and levels of organisation.

Figure 11.1 The polycentric governance complex for climate change.

11.2.1 Intergovernmental Bodies

Many intergovernmental bodies play important roles in climate governance (see Chapter 2). Many act as orchestrators, as discussed in what follows; some are potential intermediaries. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement are the core of the regime. They encompass multiple organs – including the Conference of the Parties (COP), COP presidencies and the UNFCCC secretariat – and diverse subsidiary bodies, such as the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and the Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN). UNFCCC organs have also created specialised institutions to promote voluntary commitments. Closely linked to the UNFCCC are its financial mechanisms and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Numerous IGOs address climate policy (van Asselt, Reference van Asselt2014). These include the Office of the United Nations Secretary-General (UNSG), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and other United Nations (UN) agencies, and the High-Level Political Forum on sustainable development. International financial institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank, provide finance and expertise. All of these act as orchestrators. Limited-membership climate ‘clubs’ include the G20 and the Major Economies Forum. Multilateral treaties with climate impacts include the Montreal Protocol and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

11.2.2 National Actions

National laws, policies and commitments are central modes of climate governance (see Chapter 3). NDCs under the Paris Agreement are ‘nationally determined’, but subject to review and expectations of increasing ambition. Some governments have separately adopted innovative climate policies (Jordan and Huitema, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014a, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014b); a few are active orchestrators (Abbott and Hale, Reference Abbott and Hale2014). Overall, however, because current national actions fall well short of what is needed to achieve the Paris Agreement goals, national actions remain important targets of climate orchestration.

11.2.3 Subnational Actions

The laws and policies of cities, provinces and other subnational governments are increasingly important in climate governance (see Chapter 5). Subnational governments have made extensive climate commitments – individually, through transnational associations and through the voluntary commitment system (Betsill and Bulkeley, Reference Betsill and Bulkeley2006; Bulkeley, Reference Bulkeley2010; Widerberg, Pattberg and Kristensen, Reference Widerberg, Pattberg and Kristensen2016; see also Chapter 4). Yet local actions too remain targets of orchestration. Highly institutionalised associations – such as C40 Cities, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, the Covenant of Mayors and the World Mayors Council on Climate Change – act as orchestrators and intermediaries.

11.2.4 Private Initiatives

Private activities are the source of most greenhouse gas emissions and so are the ultimate targets of climate governance. Until recently, the climate regime focused heavily on national commitments. Yet since the 1990s, business groups, environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other private actors have created numerous voluntary initiatives outside of UNFCCC processes (Abbott, Reference Abbott2012; Abbott, Green and Keohane, Reference Abbott, Green and Keohane2016; Widerberg et al., Reference Widerberg, Pattberg and Kristensen2016). Many reflect the self-organisation highlighted by polycentric governance theory.

Some initiatives include governments or IGOs; many are purely private. Examples include the Verified Carbon Standard (business), the Gold Standard (civil society), the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (business and civil society) and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) (business, civil society and government). These initiatives set standards for private behaviour, provide financing, carry out operational activities such as registering carbon offsets and promote information exchange. They can be significant intermediaries.

11.2.5 Voluntary Commitment System

Building on precedents in the sustainable development regime (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017), a VCS encouraging voluntary commitments by non-state actors has been developed since 2014, when the UNSG sponsored the UN Climate Summit to catalyse voluntary commitments. At COP20 in Lima in 2014, the current and incoming presidencies, the UNSG and the UNFCCC secretariat launched the Lima-Paris Action Agenda (LPAA) to showcase commitments and encourage new ones; in parallel, they established the Non-state Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) portal, an online registry which now lists more than 12,500 commitments. COP21 in Paris accepted additional commitments and agreed to name two ‘high-level champions’ to promote voluntary initiatives. At COP22, the first champions launched the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action (MP) to ‘catalyse and support climate action by Parties and non-Party stakeholders in the period from 2017–2020’ (Global Climate Action Champions, 2016; see also Chapter 4).

This review demonstrates the polycentric character of climate governance – the institutional complex includes ‘multiple governing authorities at different scales rather than a mono-centric unit. Each unit … exercises considerable independence to make norms and rules within a specific domain (such as … a local government, a network of local governments, … a national government, or an international regime)’ (see Chapter 1, quoting Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010b). It also highlights the range of organisations that act as orchestrators and intermediaries, and the targets’ orchestration addresses. We now consider how these organisations emerge and interact.

11.3 Ordering: Decentralised and Strategic

Polycentric governance theory emphasises decentralised, horizontal ordering, both in the formation of organisations and in their ongoing interactions. Orchestration – and related techniques including delegation (Green, Reference Green2014) and direct regulatory cooperation (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015) – challenge these understandings. They involve more strategic interventions – that is, actions that are part of a plan designed to achieve an overall goal – that are often taken at higher governance levels. This section compares these two perspectives and introduces orchestration in greater detail.

11.3.1 Decentralised Ordering

Self-organisation is ‘a key underlying concept in the polycentric literature’ (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 51). Considering organisational formation, Elinor Ostrom and colleagues analysed the ability of small local communities to self-organise common-pool resource management systems, without mandatory regulation or other hierarchical interventions (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990, Reference Ostrom2010a; Poteete, Janssen and Ostrom, Reference Poteete, Janssen and Ostrom2010). In appropriate conditions, local communities can overcome free-rider incentives (in part due to local co-benefits), build trust and overcome collective action problems that challenge larger groupings. In later work on climate change, Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010b) noted the burgeoning activities of subnational governments, equating these with community self-organisation, and called for many small-scale, multilevel climate actions, in addition to monocentric national and international actions (see Chapter 1).

The focus on mutual adjustment among organisations derives from studies by Vincent Ostrom and colleagues of local government authorities (Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren, Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961; Bish and Ostrom, Reference Bish and Ostrom1973). Many metropolitan areas feature multiple authorities with similar functions, such as local police forces. The then-dominant approach to public administration favoured consolidating these into unitary agencies. Ostrom argued, however, that local units are often more effective – they better reflect local preferences, better provide services requiring personal contact and are more responsive and efficient than ‘monopolistic’ unitary authorities. In addition, while critics emphasised the supposed duplication and inefficiency of multiple authorities, Ostrom found that horizontal ordering often avoided those problems: authorities coordinated their activities, contracted for services, created dispute resolution procedures and competed (e.g. on taxes) in ways that promoted efficiency.

Other literatures on institutional complexity likewise emphasise decentralised ordering (see Chapter 10). The organisational fields literature (Dingwerth and Pattberg, Reference Dingwerth and Pattberg2009) emphasises isomorphism among organisations with similar functions; such organisations often take on similar features, procedures and rhetoric through social interactions such as mimicry and common professional norms (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1991). Organisational ecology (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Green and Keohane2016) emphasises competition for resources – from funding to legitimacy – among similar organisations. Competition influences the types and numbers of surviving organisations and leads organisations to seek specialised ‘niches’, structuring the complex. Gehring and Faude (Reference Gehring and Faude2014) argue that the members of multiple organisations – states, in their examples – enjoy the flexibility polycentricity offers, but also want their organisations to operate effectively. They therefore promote ‘decentralised coordination’, reducing or managing inefficient overlaps.

11.3.2 Strategic Ordering and Orchestration

Scholars have also identified more centralised, strategic approaches – still short of mandatory control – designed to enhance organisational formation and ordering (Isailovic, Widerberg and Pattberg, Reference Isailovic, Widerberg and Pattberg2013; see also Chapter 10). Under the heading of ‘meta-governance’, or the governance of governance, scholars consider how authorities ‘at a higher level of decision-making’ (Beisheim and Simon, Reference Beisheim and Simon2015: 8) – governmental or non-governmental – structure and manage interactions among lower-level organisations (Derkx and Glasbergen, Reference Derkx and Glasbergen2014). In climate governance, Betsill et al. (Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015) and van Asselt and Zelli (Reference van Asselt and Zelli2014) argue that the UNFCCC has the capacity to coordinate and strengthen linkages among governmental and private governance organisations.

Orchestration is consistent with the meta-governance approach. Orchestration is indirect – an orchestrator works through intermediaries, rather than directly, to regulate or provide benefits to targets. It thus differs from direct modes of governance, including mandatory regulation and regulatory cooperation. A governor can use orchestration to enter new fields where intermediaries possess experience, contacts or authority it lacks, or where its own entry is contested.

Orchestration is also soft – while the orchestrator typically possesses some authority, in an orchestration relationship it cannot impose or enforce mandatory obligations on intermediaries; it must enlist organisations that share broadly similar goals and guide their behaviour through inducements and incentives. It thus differs from hard modes of governance, both direct (regulation) and indirect (delegation).

The techniques of orchestration address different points in the intermediary’s life and policy cycles. Initially, the orchestrator enlists the cooperation of existing intermediaries or catalyses the formation of new ones. It then encourages and assists intermediaries and steers their behaviour in line with its goals. Where there are multiple intermediaries, it coordinates their actions. All of these techniques rely on soft inducements: persuasion, convening relevant actors, material and ideational support (financing, guidance, technical assistance) and reputational incentives (recognition or endorsement, shaming). Support and endorsement simultaneously enhance intermediary capabilities and enable steering – the orchestrator can direct support to desired activities or make support conditional on them. The orchestrator may also mobilise persuasion, support and reputational incentives from third parties, multiplying its influence.

Governors of all types typically orchestrate when they lack certain capabilities needed for stronger forms of governance (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015). IGOs, for example, often lack sufficient authority for hard, direct governance, especially vis-à-vis private actors. While many IGOs have substantial expertise, they frequently lack material resources and other capacities for demanding operational activities. However, even strong, well-resourced organisations, including states, may turn to orchestration where direct or mandatory action would entail high political or material costs. While orchestration may be less powerful than mandatory control, it has proven influential in many settings (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015). When governors lack strong hierarchical authority, or share the relevant authority with others, it may be the only strategy available.

Diverse actors and organisations – governmental and non-governmental – act as orchestrators, but research suggests several qualities that influence their success (Abbott and Hale, Reference Abbott and Hale2014; Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015). An orchestrator must have sufficient agency to apply the techniques of orchestration; a body like the High-Level Political Forum, which includes all UN member states, meets for short periods and lacks its own staff, will encounter problems of agency (Abbott and Bernstein, Reference Abbott and Bernstein2015). An entrepreneurial organisational culture facilitates orchestration and makes its use more likely. Inducements such as convening, persuasion and endorsement are more influential where the orchestrator possesses significant legitimacy and authority, derived from its focal institutional position, achievements, expertise or moral reputation. An orchestrator must possess or be able to mobilise sufficient resources. Connections to potential intermediaries are helpful but not essential.

The orchestrator is often at a higher governance level than its intermediaries; for example, the European Commission orchestrates networks of Member State regulators, and many IGOs orchestrate NGOs. Even here, however, orchestration remains non-hierarchical: intermediaries respond because of shared goals, persuasion, inducements and other incentives, not mandatory controls. Respected organisations may also orchestrate their peers (Abbott and Hale, Reference Abbott and Hale2014).

A governor can orchestrate only if suitable intermediaries are available. As Section 11.2 details, climate orchestrators benefit from many potential intermediaries, including IGOs, associations of subnational governments and private transnational initiatives. Where appropriate intermediaries are lacking, orchestrators often catalyse their creation, convening relevant actors and using persuasion, support and other incentives to encourage the formation of organisations with desired goals and structures. Some orchestrators – notably UNEP, whose role in creating private environmental initiatives provided the original model for orchestration (Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2009) – have catalysed numerous organisations, strongly suggesting that they find spontaneous self-organisation an unreliable source of suitable intermediaries.

Orchestration is valuable for structuring and coordinating intermediary relationships where mutual adjustment is insufficient (Abbott and Hale, Reference Abbott and Hale2014; Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015). An orchestrator can use persuasion, material and ideational support and reputational incentives to encourage organisations to reduce overlaps, manage conflicts, fill governance gaps, collaborate and otherwise govern more effectively. Intermediaries may welcome coordination, which can increase their legitimacy and effectiveness.

11.4 Orchestration in Climate Governance

This section examines how orchestration has been used to catalyse, encourage, support, steer and coordinate diverse actors and organisations in climate governance. While many climate initiatives have emerged through self-organisation and engage in mutual adjustment, orchestration of organisational formation and ordering is nonetheless widespread. As in other areas, climate orchestration serves two broad purposes: ‘managing states’, encouraging strong national commitments and promoting implementation and compliance; and ‘bypassing states’, encouraging non-state commitments and actions where orchestrators view state actions as insufficient (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015: 11).

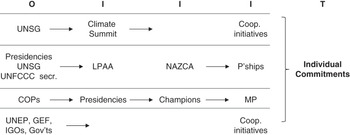

11.4.1 Voluntary Commitment System

In developing the climate VCS, orchestrators emulated techniques pioneered in sustainable development governance (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017). Sustainable development summits, supported by the UNSG, focused on catalysing partnerships that could act as intermediaries, promoting and coordinating individual actions by partners. They enlisted existing networks, including the UN Global Compact, originally an intermediary established by the UNSG and UN agencies to elicit business commitments to social responsibility, including through its Caring for Climate programme. They helped organise commitments into ‘action networks’ – such as Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) – that act as intermediaries, eliciting and coordinating commitments and promoting accountability. They offered modest ideational support but relied primarily on reputational inducements, including public recognition and inclusion in an online registry.

The UNSG initiated the climate VCS at the 2014 UN Climate Summit, convening businesses, NGOs, subnational governments and even states and IGOs, and using persuasion and recognition to elicit commitments to climate action. The UNSG provided ideational guidance by encouraging commitments in areas of need – ‘action areas’ such as climate finance, energy and cities. It encouraged multi-stakeholder ‘cooperative initiatives’ that could function as intermediaries – like partnerships and action networks – eliciting, coordinating and managing individual commitments.

The Peruvian and French presidencies, the UNSG and the UNFCCC secretariat established the LPAA to encourage additional ‘transformative’ initiatives in the run-up to Paris. The NAZCA registry was designed to ‘showcase’ cooperative initiatives and other commitments, providing soft reputational incentives for organisational formation while facilitating collaboration and accountability. The orchestrators implicitly endorsed several organisations selected to provide the commitment information that NAZCA aggregates. Providers include the Carbonn Climate Registry and the Covenant of Mayors (subnational commitments), and the UN Global Compact and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) (business commitments).

COP21 recognised new commitments at high-level public events. The COP decision adopting the Paris Agreement endorsed the VCS, welcoming voluntary commitments, encouraging NAZCA registration, urging governments to participate in cooperative initiatives and agreeing to recognise new commitments at future meetings. COP21 also created two new intermediaries: ‘high-level champions’ from the current and incoming presidencies, charged with promoting and supporting ‘voluntary efforts, initiatives and coalitions’ (see Chapter 4).

At COP22, the first ‘champions’, from France and Morocco, initiated the MP, a framework for orchestrating voluntary commitments, led by the champions, presidencies and UNFCCC secretariat, plus the UNSG as ‘global convenor’, reflecting its unique convening authority. These actors commit to:

(1) Catalyse initiatives, convening stakeholders and governments through regional and thematic meetings, technical examination processes, the Global Forum of Alliances and Coalitions, COP ‘action days’ and other events. They will provide ideational guidance by setting priorities, and reputational incentives by highlighting successful initiatives. They will use persuasion and recognition to promote increased ambition and Southern participation and will encourage third-party support.

(2) Track progress, requiring initiatives to register on NAZCA and provide regular updates on progress as conditions of participating in the MP. New criteria for commitments ‘encourage’ concrete goals, clear targets, scale, sufficient resources and transparency. Tracking is intended to promote accountability and to identify areas where additional actions are needed.

(3) Showcase successes, publicising ambitious initiatives in priority areas through NAZCA, COPs and other events. Showcasing creates incentives to emulate successes, provides learning opportunities and allows for modest steering.

(4) Report achievements to governments. The champions will identify options and priorities suggested by successful initiatives for technical examination processes, decisions on NDCs and COP deliberations.

As part of the VCS, governments and IGOs have initiated, supported and steered many cooperative initiatives. For example, UNEP and partners launched several energy efficiency initiatives in 2014, with financial support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The Efficient Appliances and Equipment Partnership brings together UNEP and the United Nations Development Programme, the International Copper Association and the Natural Resources Defense Council to promote efficient appliances. Through United for Efficiency, UNEP and partners help developing countries transition to efficient products. UNEP and Norway launched the 1 Gigaton Coalition to help countries measure and report emissions reductions from energy efficiency projects. All these initiatives collaborate with the SE4All action network.

Figure 11.2 Orchestrating voluntary climate commitments.

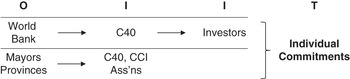

Orchestrators have used similar techniques to promote voluntary commitments by cities, provinces and other subnational governments (Figure 11.3). Among other intermediaries, orchestrators worked through transnational associations. For example, the World Bank provided significant financial support to C40 Cities, and collaborates with it in the Carbon Finance Capacity Building Program, encouraging carbon finance for ‘emerging megacities of the South’ (CFCB, n.d.). Entrepreneurial local leaders also used orchestration to catalyse, support and steer these associations. For example, illustrating orchestration among peers, Ken Livingstone, then the mayor of London, initiated C40 Cities in 2005, convening the mayors of 18 ‘megacities’ to collaborate on emissions reductions. Livingstone later invited the Clinton Climate Initiative (CCI) to collaborate on concrete projects. A subsequent C40 chair, Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York, integrated the work of C40 and Clinton Climate Initiative staff.

Figure 11.3 Orchestrating subnational commitments.

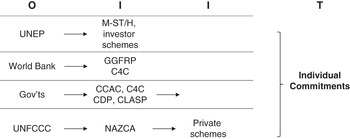

11.4.2 Private and Public-Private Climate Schemes

Businesses, NGOs and other actors have created numerous private and public-private climate initiatives outside the VCS and before its creation (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011; Abbott, Reference Abbott2012; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova and Bäckstrand2012; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Andonova and Betsill2014) (figure 11.4). Many initiatives set standards for the behaviour of signatories – often relating to carbon offsets and markets, including emissions measurement, accounting and disclosure (Green, Reference Green2014; Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Green and Keohane2016) – or elicit commitments from companies and other targets. Others conduct or finance pilot projects and other operational activities, facilitating learning and enabling disclosure systems, carbon markets and similar mechanisms. Many are now registered on NAZCA.

Figure 11.4 Orchestrating private climate schemes.

Participating actors created most of these schemes on a bottom-up basis, but orchestrators facilitated a number of them. UNEP has been particularly active, convening stakeholders, catalysing the formation of transnational environmental schemes and supporting new initiatives. As noted earlier, UNEP helped launch the multi-stakeholder Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997, endorsing it and providing significant ideational and material support. The UN Global Compact later endorsed GRI standards, which address carbon emissions and other environmental issues, for use by participating firms.

UNEP collaborated with Sweden and other governments to establish the CCAC to promote and facilitate action on short-lived climate pollutants. Through its Finance Initiative, and together with the UN Global Compact, UNEP coordinated the negotiation of the Principles for Responsible Investment and the Principles for Sustainable Insurance, which elicit commitments from investors and insurers to consider environmental, social and governance issues, including climate change. The UNEP Finance Initiative also sponsors the Portfolio Decarbonization Coalition, which encourages low-carbon investments, and the Sustainable Energy Finance Initiative, which supports investors in financing clean energy technologies.

The World Bank has been another active orchestrator (Hale and Roger, Reference Hale and Roger2014), helping to establish schemes such as the Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership and Connect4Climate. National governments have collaborated with IGOs in catalysing initiatives such as Connect4Climate, and have independently supported initiatives such as CDP and the Collaborative Labeling and Appliance Standards Program (CLASP), a multi-stakeholder initiative to improve the environmental performance of appliances and equipment.

11.4.3 National Commitments and NDCs

Domestic political forces likely drive most national climate policies and NDCs (see Chapter 3); UNFCCC organs also directly encourage ambitious state actions. But some national commitments and policies derive in part from orchestration (Figure 11.5). The 2014 UN Climate Summit elicited national commitments – including commitments related to future NDCs – directly from governments, and indirectly through cooperative initiatives that include governments. For example, 40 governments, with many non-state actors, endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests; some committed to new forestry policies while others pledged financial support. Forty governments also helped launch the Global Energy Efficiency Accelerator Platform to support subnational governments.

Figure 11.5 Orchestrating NDCs and national policies.

The UNFCCC engages intermediaries to facilitate strong national actions. For example, within its Technology Mechanism, the Technology Executive Committee (TEC), which consists of technology experts, provides policy recommendations to governments. The Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN), which UNEP and the UN Development Programme host, arranges technical assistance on technology transfer (see Chapter 15). The CTCN operates as an orchestrator, coordinating a network of technology organisations that provide assistance to governments. Such assistance can catalyse ambitious actions, provide crucial ideational resources and steer national decision-makers towards the most beneficial actions.

UNFCCC Technical Expert Meetings engage governmental and non-governmental experts, who act as intermediaries promoting national adoption of ‘best practice’ mitigation policies with sustainable development co-benefits, reducing the costs and increasing the benefits of national action. The current and incoming presidencies, with the UNFCCC secretariat and other IGOs, launched the NDC Partnership in 2016 to link countries with the financial and technical resources needed to implement NDCs.

The Paris Agreement initiated three review processes, which may include elements of orchestration as well as direct interactions among governments and with UNFCCC officials (van Asselt et al., Reference van Asselt, Hale and Abbott2016):

(1) Article 13 provides for review of national progress in implementing NDCs, based on national reports and other information. In addition to peer governments and the secretariat, this process will engage ‘technical experts’, who will act as intermediaries in assessing the information received. In addition, Article 13 review is intended to be ‘facilitative’ – it will identify barriers to national implementation, then encourage third parties, such as CTCN and the Green Climate Fund, to provide support that helps governments overcome those barriers.

(2) Article 14 provides for a ‘global stocktake’ every five years from 2023, designed to inform periodic updates of NDCs. Stocktake procedures will primarily entail direct interactions among governments, but they could engage diverse intermediaries – including the secretariat, technical experts and other non-state actors – as information providers and persuaders.

(3) Article 15 calls, in broad terms, for an implementation and compliance mechanism. It will involve an ‘expert-based’ committee; here, too, experts that are sufficiently independent could be considered intermediaries. This mechanism will again facilitate third-party support to address identified needs.

Even if non-state actors play only limited roles in formal review processes, their independent assessments have significant influence (van Asselt, Reference van Asselt2016). Governments and IGOs can encourage, support, facilitate and publicise such assessments through orchestration.

The World Bank has created intermediaries to facilitate climate finance, supporting NDC implementation and policy and technical innovations. Its four Climate Investment Funds (CIFs) provide concessional financing for innovative policies in their domains, allowing countries to test new approaches, attract co-financing and qualify for new funding streams. While the World Bank and other IFIs support and guide the CIFs, they are independent organisations, governed by committees comprising donor and recipient governments, with diverse private and governmental observers. As such, they can tap varied public and private resources, material and ideational.

11.5 Climate Orchestration and Decentralised Ordering

The prevalence of climate orchestration, described in the previous section, has important implications for three of the central propositions of polycentric governance theory outlined in Chapter 1. I consider two of those propositions here, and a third in the concluding section.

11.5.1 Local Action

Polycentric governance theory asserts that new organisations emerge spontaneously as actors self-organise in local settings. Numerous organisations have entered climate governance in recent years – notably private and subnational initiatives – and many have self-organised at relatively small scales. In other cases, however, orchestrators have encouraged and facilitated organisational formation. This suggests that the spontaneous local action/self-organisation proposition is incomplete: observers of polycentric systems should also look for strategic actions that catalyse and incentivise organisational formation.

The entire climate VCS was a strategic construction. The UNSG, UNFCCC secretariat, presidencies and ultimately COP21 (O) worked through the champions, cooperative initiatives, subnational government associations and other intermediaries (I) to establish a system to elicit and register thousands of voluntary commitments from non-state actors (T). UNEP, the World Bank, other IGOs and governments also catalysed the formation of many cooperative initiatives and multi-stakeholder organisations, within the VCS and outside it. Under the MP, many of these actors are actively catalysing new initiatives. These actions have changed the shape of climate governance, created new opportunities for participation and new forms of commitment, and initiated new flows of information and ideas.

Orchestrators have utilised a range of techniques; while none involves mandatory control, all facilitate or influence desired behaviours through diverse pathways. Orchestrators enlisted existing intermediaries (COP presidencies, information providers) and catalysed formation of new ones (cooperative initiatives) through convening, persuasion and reputational incentives. They provided positive incentives for organisational formation through public recognition, endorsement and ‘showcasing’ – at public events, through NAZCA and in national and international policy processes. They provided ideational support to new organisations through information and guidance (action areas, MP priorities). Most provided little direct material support, but did facilitate third-party financing.

11.5.2 Mutual Adjustment

Polycentric governance theory asserts that organisations in polycentric systems spontaneously coordinate their behaviour through mutual adjustment, without centralised intervention. Many climate governance organisations do coordinate in this fashion, though sometimes only modestly. Secretariats and scientific bodies of the Rio Conventions, including the UNFCCC, coordinate through the Joint Liaison Group (CBD, 2013). Environmental IGO secretariats coordinate through the UN Environment Management Group. National governments can coordinate within COPs, the UN Environment Assembly and other institutions. Subnational governments collaborate through transnational associations, and private actors through multi-stakeholder initiatives and networks.

In other cases, however, orchestrators shape climate governance and encourage coordination among constituent initiatives. This suggests that the mutual adjustment proposition too is incomplete: observers of polycentric systems should also look for strategic actions that promote ordering and coordination.

States, IGOs and other orchestrators structure climate governance in several ways:

(1) They encourage initiatives of particular kinds. The UN Climate Summit encouraged ‘cooperative initiatives’, commitments in specified areas and government commitments relevant to NDCs. The LPAA and Marrakech Partnership adopted mandatory criteria for voluntary commitments, an approach known as ‘directive orchestration’ (Abbott and Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2009). Only initiatives meeting those criteria may register on NAZCA and receive other reputational benefits, although the criteria are not always vigorously enforced.

(2) They support intermediary initiatives that further favoured goals. The LPAA, MP and COP ‘showcase’ commitments they identify as ‘successes’, incentivising others to emulate them. Showcasing successful non-state initiatives also helps ‘manage states’ – it demonstrates to governments the actions their citizens are willing to take, undercuts excuses for inaction (such as infeasibility and cost) and provides new policy ideas and evidence. NAZCA endorses specific data-providing organisations; the World Bank supports C40 Cities through its urban programmes.

(3) They use intermediaries to facilitate desired actions. The CTCN facilitates ambitious national policies by orchestrating experts to provide technology assistance. United for Efficiency and other UNEP-supported cooperative initiatives likewise provide technical assistance on specific topics. The World Bank works through the CIFs to provide climate finance and to encourage third-party co-financing. The NDC Partnership links governments with third-party sources of support and expertise. The MP encourages donors to support voluntary initiatives.

(4) They promote coordination. Cooperative initiatives and other multi-stakeholder schemes facilitate coordination among participants. The Global Forum of Alliances and Coalitions promotes and facilitates coordination among initiatives. One rationale for the NAZCA portal is to disseminate information that reduces the costs for initiatives to coordinate. Overall, however, efforts at coordination have been more limited than those aimed at structuring the institutional complex.

Again, these actions utilise many orchestration techniques, including convening (Global Forum), persuasion (encouraging cooperative initiatives), reputational incentives (showcasing successes), ideational support (guidance, information) and steering (criteria, priorities, highlighting successes).

11.6 Conclusions: Enhancing Climate Orchestration

11.6.1 Orchestration Is Pervasive

Orchestration pervades climate governance. Many of the organisations in Figure 11.1 act as orchestrators: UNFCCC organs including the secretariat, presidencies and COP; UNEP, the World Bank and other IGOs and IFIs; the UNSG; and national governments. These international bodies lack authority for mandatory governance vis-à-vis states and private actors; even governments encounter limits to their authority when addressing transnational problems. International bodies also lack operational capacities and material resources – even the World Bank cannot provide all the needed climate finance. As orchestration research suggests (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015), these actors engage (and help create) intermediaries able to provide the capabilities they lack.

Not every actor can orchestrate successfully, but these actors have demonstrated sufficient agency and organisational competence to do so. Some have shown unexpected entrepreneurial flair. All possess substantial legitimacy and authority with relevant audiences, based on their institutional positions, expertise and moral leadership. Only the IFIs – notably the World Bank and the GEF – have committed substantial material resources; other orchestrators rely almost exclusively on convening authority, ideational support and reputational incentives.

11.6.2 Extending Climate Orchestration

For all its prevalence, however, climate orchestration falls short in certain areas: it has produced governance arrangements that are insufficient to meet agreed mitigation and adaptation goals, pose governance problems such as accountability (see Chapter 19) or simply fail to fulfil their potential. As mandatory governance remains unavailable, additional orchestration is the most feasible way to address these shortfalls. In this section I highlight four areas where extended orchestration would be valuable.

First, while a core proposition of polycentric governance theory asserts that polycentricity promotes experimentation and policy learning (see Chapters 1 and 6), the current system does not fully realise those benefits. The diverse actions taken under NDCs and the climate VCS offer unparalleled opportunities for experimentation and learning (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017). But the system produces only ‘informal’ experiments that do not follow the logic of experimentation in the natural and social sciences, and provides no systematic learning procedures. In addition, to pursue governance goals including speed and scale, the VCS adopts so-called SMART criteria, calling for specific, measurable, achievable and time-bound initiatives; these criteria encourage the application of established approaches, discouraging innovation and experimentation.

Climate orchestrators could encourage and support IGOs, governments and non-state initiatives to conduct designed, controlled experiments on technologies and policies (formal experiments), perhaps collaborating with natural and social scientists. At the least, they should encourage and support these actors to carry out their decentralised actions in ways that promote innovation and systematic learning (informal experiments). ‘Experimentalist governance’ offers one useful model (Sabel and Zeitlin, Reference Sabel and Zeitlin2010), focusing on deliberation and peer review. An even stronger system would persuade, incentivise and support states and non-state actors to design and implement policies and interventions with an eye to experimentation and learning – adopting policies provisionally, coordinating their interventions to limit gaps and overlaps, defining important parameters to maintain comparability, keeping consistent records, disclosing results and engaging in systematic comparison and analysis of outcomes, with expert input where necessary (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017).

Orchestrators of the climate VCS could work through cooperative initiatives, local government associations and mechanisms such as the MP to encourage and facilitate these approaches among non-state actors; other orchestrators, such as UNEP, could work through independent initiatives. The UNFCCC could use the Article 13 transparency mechanism, the Technology Mechanism and other processes to promote them among governments.

Second, the MP aims to accelerate and enhance voluntary initiatives. Its broad strategies – catalysing action, tracking progress, showcasing and reporting – are laudable. But its techniques remain unclear (Chan et al., Reference Chan, van Asselt and Hale2015; Chan, Brandi and Bauer, Reference Chan, Brandi and Bauer2016). How can orchestrators effectively catalyse ambitious commitments, ratchet up their ambition, encourage financial support, promote Southern participation and ensure greater accountability? While a full discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, the presidencies, champions, UNFCCC secretariat and UNSG should solicit advice from diverse stakeholders and experts, then design and implement a suite of concrete orchestration techniques to maximise the impact of the climate VCS.

Third, the Paris Agreement relies on NDCs, subject to periodic review and updating. The aim is to create a ratcheting dynamic, gradually increasing ambition. But review procedures are explicitly non-hierarchical and facilitative; effective orchestration is thus essential. Based on the foregoing discussion, an orchestration strategy might incorporate at least three elements. UNFCCC organs and leading governments should seek to embed influential intermediaries – e.g. IGOs, technical experts, finance providers, NGOs – into review processes, to facilitate action, introduce information and ideas and exert subtle pressures on governments (van Asselt et al., Reference van Asselt, Hale and Abbott2016). These and other orchestrators, such as UNSG, should mobilise diverse intermediaries to develop and provide willing governments information on cost-effective mitigation and adaptation strategies, with the ideational and material resources to implement them (Victor, Reference Victor, Stavins and Stowe2016). Finally, orchestrators should ensure that ideas, information and evidence from the ‘groundswell’ of voluntary non-state initiatives are clearly communicated to governments in the context of decisions on NDCs, both for learning and for the political impact of their demonstration effects.

Fourth, while climate orchestrators have helped structure the institutional complex, as by encouraging initiatives of particular kinds, they have done relatively little to coordinate the actions of those initiatives. To encourage and incentivise efficient coordination among national government policies and NDCs, UNFCCC organs and other orchestrators could work through the Technology Mechanism, Technical Expert Meetings, CIFs and public-private cooperative initiatives, as well as regional bodies and other IGOs. They could introduce experts and other influential intermediaries into these processes to persuade and provide information and assistance.

For voluntary non-state commitments, cooperative initiatives may coordinate participants internally, but orchestrators of the climate VCS could more actively encourage them to do so, through MP criteria, the Global Forum and other processes. UNEP, with a mandate for coordination and close relations with many initiatives, could assume a larger coordinating role. The most ambitious vehicles for non-state coordination in environmental governance are the sustainable development action networks. Networks such as SE4All and Every Woman Every Child have developed substantial agency, coordinate participating initiatives by tracking progress and establishing priorities, and operate accountability mechanisms. Similar networks would be valuable additions to climate governance.