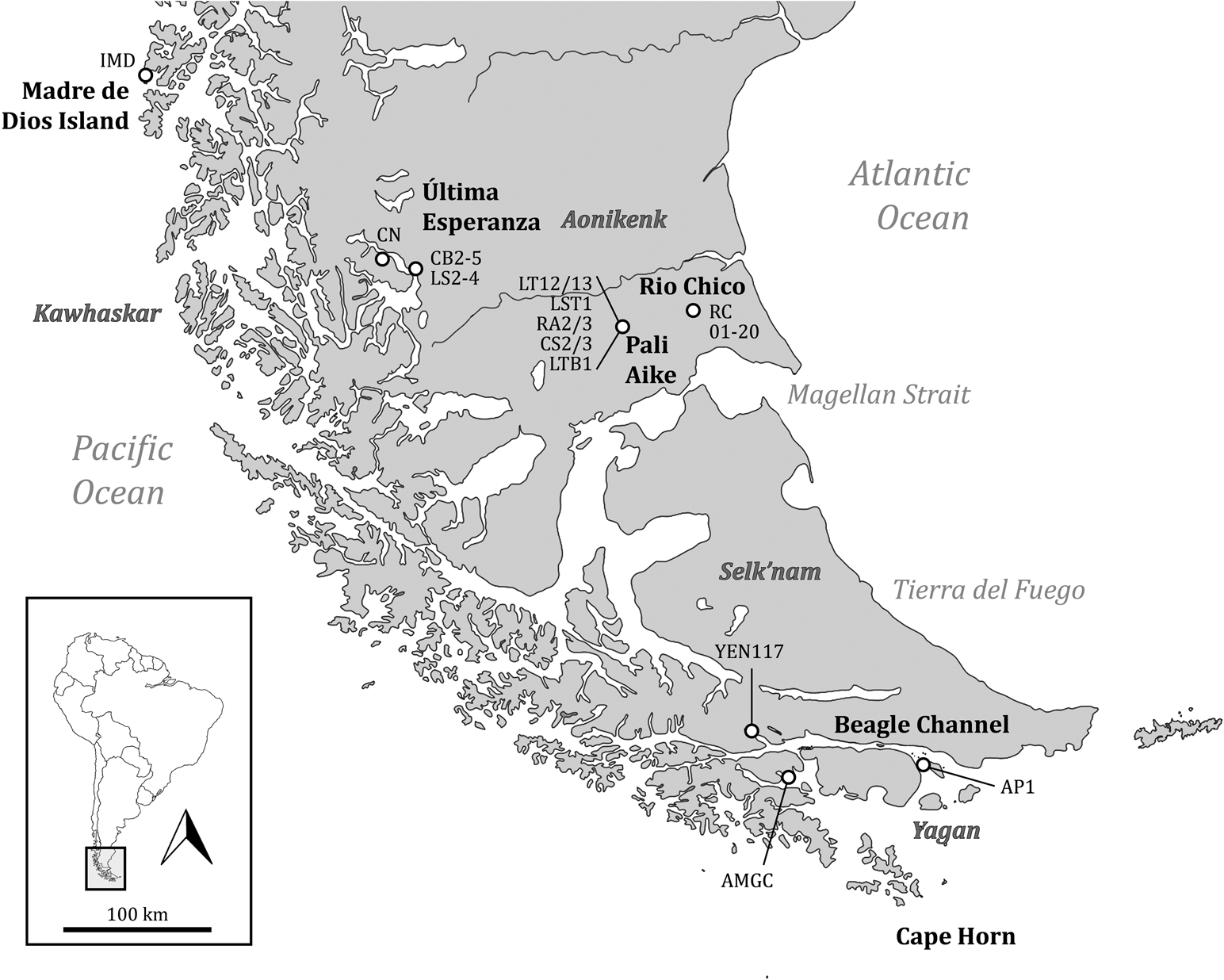

For many years, archaeological research in the southern Patagonia archipelago did not discover any rock art sites, but this has been gradually changing. Today, such sites have been reported across an extensive zone stretching from Madre de Dios Island to Cape Horn (González et al. Reference González, Gañán and Serrano2014; Jaillet et al. Reference Jaillet, Fage, Maire and Tourte2010; Legoupil and Prieto Reference Legoupil and Prieto1991; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Cordero and Artigas2016). Curiously, no rock art site had been reported to date on the largest island of the archipelago, the Isla Grande of Tierra del Fuego, which also has the longest recorded occupational history (e.g., Oría and Tivoli Reference Oría and Tivoli2014; Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999a). During our investigations at Yendegaia Bay, on the north shore of the Beagle Channel (the southern coast of this big island) and in the ancestral territory of the Yagán people, we discovered the first site containing rock paintings (Figure 1). Archaeological and ethnographic evidence suggest that the mobility of these canoe-faring people who navigated around the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, from the Gulf of Penas to Cape Horn, enabled regular contact with populations with different cultural traditions. These included what have come to be called marine hunter-gatherers, the Kawashkar in the Magellan Strait archipelago; the land-based hunter-gatherers known as the Selk'nam, who inhabited the Isla Grande; and their mainland neighbors in continental Patagonia, the Aonikenk. We propose that the motifs documented at Yendegaia Rockshelter provide new evidence of these interregional interactions: they bear graphic resemblances that suggest they formed part of a shared system of information circulation, albeit with local specificities.

Figure 1. Distribution of the localities and archaeological sites mentioned in the article.

Many studies focusing on social interactions among hunter-gatherer groups have argued that they maintained social alliances to reduce socioenvironmental pressures and to favor social reproduction (Borrero et al. Reference Borrero, Martín, Barberena, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011; Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009a; Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Cabello, Pimentel, Sepúlveda and Cornejo2012; Gamble Reference Gamble1982; Jochim Reference Jochim and Bailey1983; Webb Reference Webb1974; Whallon Reference Whallon2006, Reference Whallon, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011; Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977). These authors have shown that in desert, semidesert, and periglacial environments, such as the Fuego-Patagonia region, the circulation of shared motif types, whether on fixed supports (rock art) or portable ones (mobile art, body art), contributed to the flow of information, the construction of social networks, and the formation of alliances among distant groups.

The visual scenes found in such harsh environments are comparable to those recorded for hunter-gatherer rock art sites located in the southernmost part of the American continent. Given these similarities, researchers working in localities of northern, central, and south-central Patagonia have argued that the motifs captured in rock art and in portable art would have fostered interaction among the populations of the whole region (e.g., Acevedo Reference Acevedo2015; Acevedo and Fiore Reference Acevedo and Fiore2020; Carden and Borges Reference Carden, Borges and Martínez2017; Carden et al. Reference Carden, Miotti and Blanco2018; Cassiodoro et al. Reference Cassiodoro, Guichón, Re, Gómez, Svoboda and Banegas2019; Fiore Reference Fiore2006, Reference Fiore2020; Guichon Reference Guichon2018; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Re, Cordero, Guichón and Artigas2021; Re and Guichon Reference Re, Guichon, Goñi, Belardi, Cassiodoro and Re2014). Long-distance relations among the different marine- and land-based human groups of the Fuego-Patagonia archipelago were also active in historic times and are described in ethnographic sources (e.g., Borrero et al. Reference Borrero, Martín, Barberena, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011; Bridges Reference Bridges1952; Chapman Reference Chapman1977; Emperaire Reference Emperaire2002; Fitz Roy Reference Fitz Roy1839; Gusinde Reference Gusinde1986; Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999b).

Interactive social networks between groups with navigation technology are evident in the region, which would also encourage the circulation of decorated motifs found in mobile art, especially on the islands of the Strait of Magellan-Tierra del Fuego-Canal Beagle (the southern part of Isla Grande del Tierra del Fuego), the northern part of Isla Grande del Tierra del Fuego, Otway Sound (Riesco and Englefield Islands), and the southern tip of the mainland on the Brunswick Peninsula and the southeast zone of southern Patagonia (Fiore Reference Fiore2006).

In this article, we propose that the rock art of Yendegaia would have been part of that flow of social information and the expression of a strategy in which cooperation coexisted with competition (Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020). To this end, we present this new discovery along with an analysis of the corresponding historic and archaeological contexts. We then examine the distribution of rock art in the region from a quantitative perspective and finally explore the visual practices and social interactions among different localities of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago and southern Patagonian shore of the Magellan Strait.

Yendegaia Bay: Historic and Archaeological Background

The oldest evidence of human occupation in the channels of southern Tierra del Fuego dates to 7800 cal BP, when a long tradition of coastal fishing and hunter-gatherer activity emerged (e.g., Morello et al. Reference Morello, Borrero, Massone, Stern, García-Herbst, McCulloch and Arroyo-Kalin2012; Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999a; Orquera et al. Reference Orquera, Legoupil and Piana2011). Most archaeological sites are concentrated along the two shores of the Beagle Channel in what is today Chilean and Argentinean territory (Bird Reference Bird1938a, Reference Bird1946; Ocampo and Rivas Reference Ocampo and Rivas2002). These sites feature extensive and dense shell middens made up of multiple residential occupations (Bird Reference Bird1938b; Lothrop Reference Lothrop1928); their excavation has yielded a lengthy stratigraphic sequence of numerous sporadic, residential occupation events resulting from the reuse of certain spaces and the existence of defined mobility patterns (e.g., Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999a; Orquera et al. Reference Orquera, Sala, Piana and Tapia1977). In those localities where systematic surveys were conducted in the forests upland from the coastline, archaeological sites were associated with productive tasks and social functions, including hunting camps and funerary sites at rockshelters (Ocampo and Rivas Reference Ocampo and Rivas2002; Piana and Vázquez Reference Piana, Vásquez, Salemme, Santiago, Álvarez, Piana, Vásquez and Mansur2009; Piana et al. Reference Piana, Tessone and Zangrando2006). Based on these findings, it is evident that the food consumed at these sites came mainly from hunting pinnipeds, guanacos, and birds; fishing; gathering mollusks; and the occasional consumption of beached whales (Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999a; Zangrando and Tivoli Reference Zangrando and Tivoli2015).

The Yagán people, the modern-day descendants of these early populations, inhabited the Beagle Channel, Cape Horn, and the adjacent fiords at the time of European contact (Bridges Reference Bridges2001; Chapman Reference Chapman2012; Orquera and Piana Reference Orquera and Piana1999b). Generally, immediate families used bark canoes as their main mode of transportation when moving from one residential camp to another. These smaller family groups sometimes temporarily joined up with other social units for certain seasonal activities. They usually journeyed along the coast, although they also made expeditions to other islands, ventured into their interiors, and even visited the mainland occasionally for specific purposes (Bridges Reference Bridges1884; Gusinde Reference Gusinde1986; Martial Reference Martial1888).

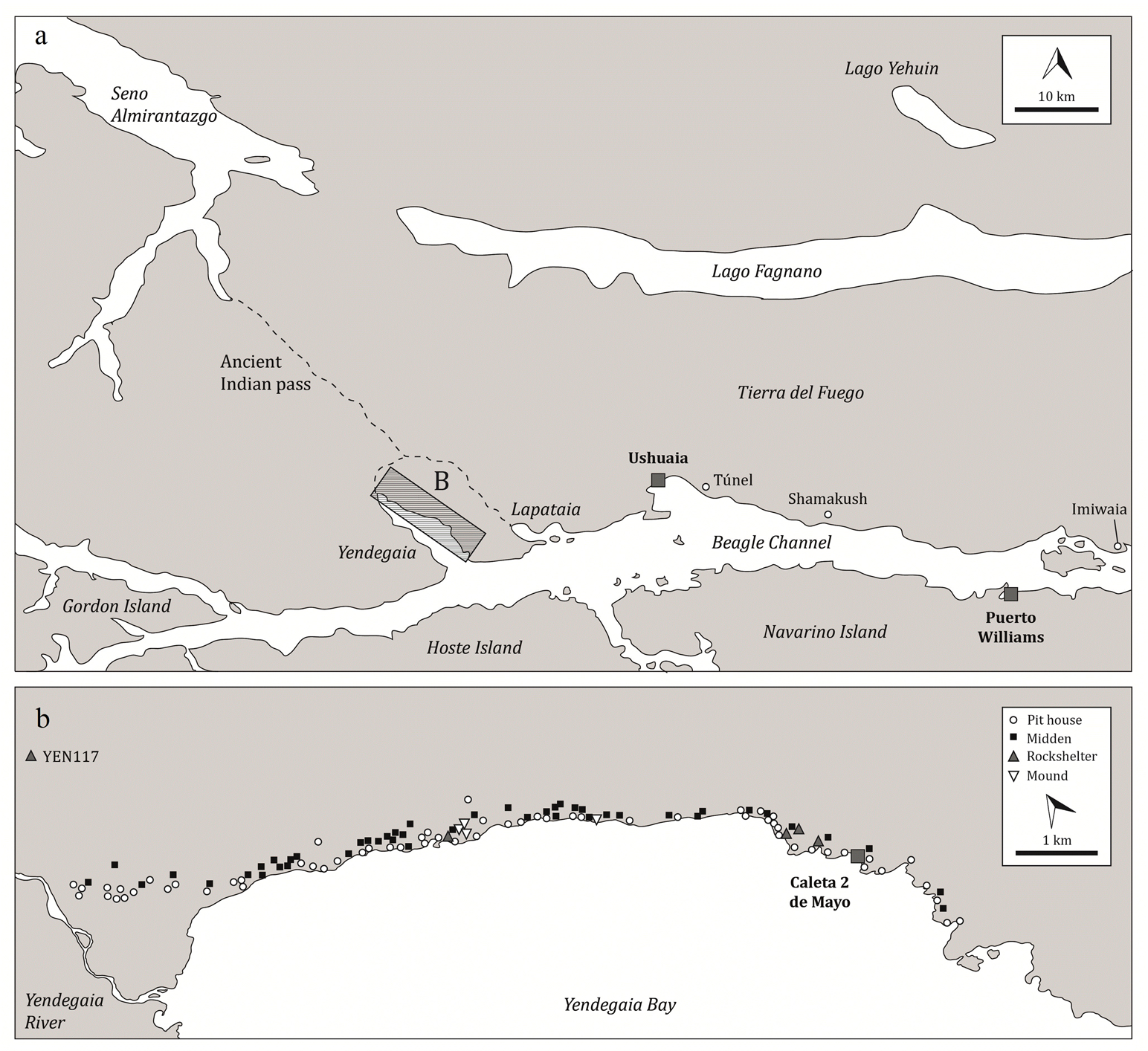

Yendegaia Bay is situated in Yagán territory, on the northern shore of the Beagle Channel (southern coast of the Isla Grande of Tierra del Fuego; Figure 2a). Giacomo Bove (Reference Bove1882, Reference Bove1883), who commanded the Argentinean Southern Expedition, published a map of the bay showing Yagán settlements, where he calculated that 40 Indigenous inhabitants lived. He was treated very well by them, he reported: they took him on three excursions where he collected skeletons that he then transported to Europe (Tafuri et al. Reference Tafuri, Zangrando, Tessone, Kochi, Maggi, di Vicenzo, Profico and Manzi2017). The year after Bove's voyage, in January 1883, the ship La Romanche dropped anchor at Yendegaia. It was part of the French scientific expedition commanded by Captain Louis-Ferdinand Martial (Reference Martial1888). In his writings, the captain described a half-dozen huts inhabited by local Indigenous people, some of whom approached the ship, came up on deck, and agreed to be photographed (Fiore and Varela Reference Fiore and Varela2009). Several years later, Bove's hunch that there was a passage from Almirantazgo Sound to Yendegaia was proven correct when Swiss explorer Carl Skottsberg (Reference Skottsberg1911) reported it as an ancient “Indian” route (Figure 1). US painter Rockwell Kent (Reference Kent1924) followed this route in December 1922 and along the way encountered the remains of an Indigenous dwelling, corroborating its use as a “traditional passage” (Prieto et al. Reference Prieto, Chevallay and Ovando2000).

Figure 2. Location of (a) Yendegaia Bay and (b) archaeological sites identified at the bay.

Junius Bird (Reference Bird1938b) conducted the first systematic archaeological studies on the bay. On the northeast shore, near Caleta 2 de Mayo village, he excavated a rockshelter with a dense shell midden almost 2.7 m deep; using the methods and criteria of that time, he identified a continuous occupational sequence. Bird (Reference Bird1938a) also identified two cultural moments: an older one in the lower strata that he attributed to the “Shell-Knife Culture” and one in the upper strata, which he called the “Pit-House Culture” and linked to the Yagán culture.

In recent decades, the archaeological record of the bay has grown as a result of the construction of a wharf and a new route connecting the village with the island's interior (Bustos Reference Bustos2007; Constantinescu Reference Constantinescu2006; Reyes and San Román Reference Reyes and Román2008). Our own investigations, conducted in 2016–2017, entailed systematic surveys along the northeast shore of the bay, from the Yendegaia River to the Beagle Channel (Figure 2b). This work identified 117 archaeological sites: 62 remains of semi-subterranean dwellings, 4 mounds, 46 middens, and 5 rockshelters. In one of these shelters (YEN117), we found a panel with rock paintings whose location and designs are significant to the archaeology of the region.

Yendegaia Rockshelter and Its Paintings

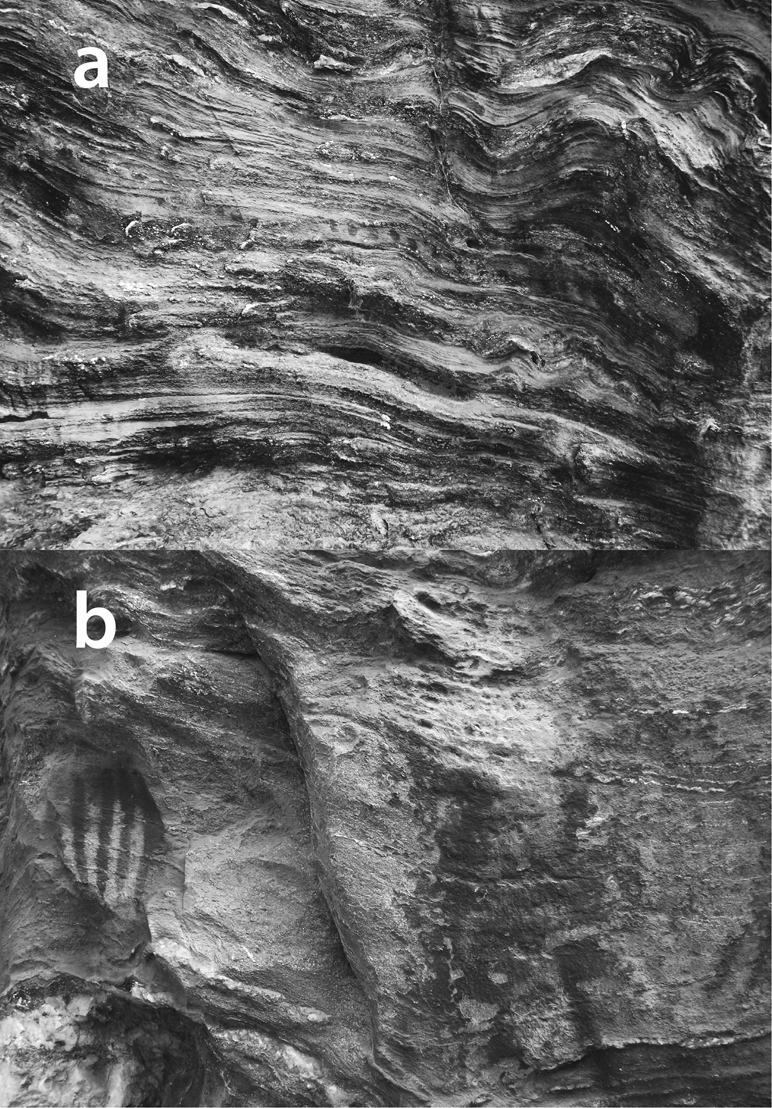

The rock wall with paintings is situated on the eastern side of the bay, some 3.5 km from the present-day shoreline. It is one face of a boulder that forms a shelter with a small rest area (12 × 4 × 1 m), located on the first terrace 23 m asl and above an extensive bogland found on the riverbank (Figure 3). No cultural material was observed on the surface of the archaeological site YEN117. The rock paintings are very visible and are placed on different planes of the rock wall in a variety of orientations, ranging from 1 m to 2.5 m above the current ground level. We recorded the paintings at the motif and panel level using our standard methodology (Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b; Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Cabello, Pimentel, Sepúlveda and Cornejo2012). Even though the paintings were very weathered, D-Stretch software enabled us to identify several motifs painted in red, some of which were in sequence or were successive repetitions (Figure 4). There are motifs based on dots—three pairs, one case with four units, and another with 20 dots (Figure 4a)—and motifs based on strokes framed by parallel vertical lines: two pairs and four elements in one case (Figure 4b). There are also 10 stains (Figure 4b) concentrated lower down on the panel (Table 1). All the motifs at the site are geometric, with minimal elements or units of dots (2–3 cm in diameter) or long linear strokes (ca. 12 cm in length) that are replicated by horizontal translation (Washburn Reference Washburn and Washburn1983). In other words, the motifs are produced by a discontinuous stroke, which makes this graphic solution very characteristic of the site—and culturally related to other designs of the region.

Figure 3. The rock wall where the rock paintings were found. (Color online)

Figure 4. Rock paintings at YEN117: (a) motifs based on dots; (b) motifs based on strokes (left) and stains (right).

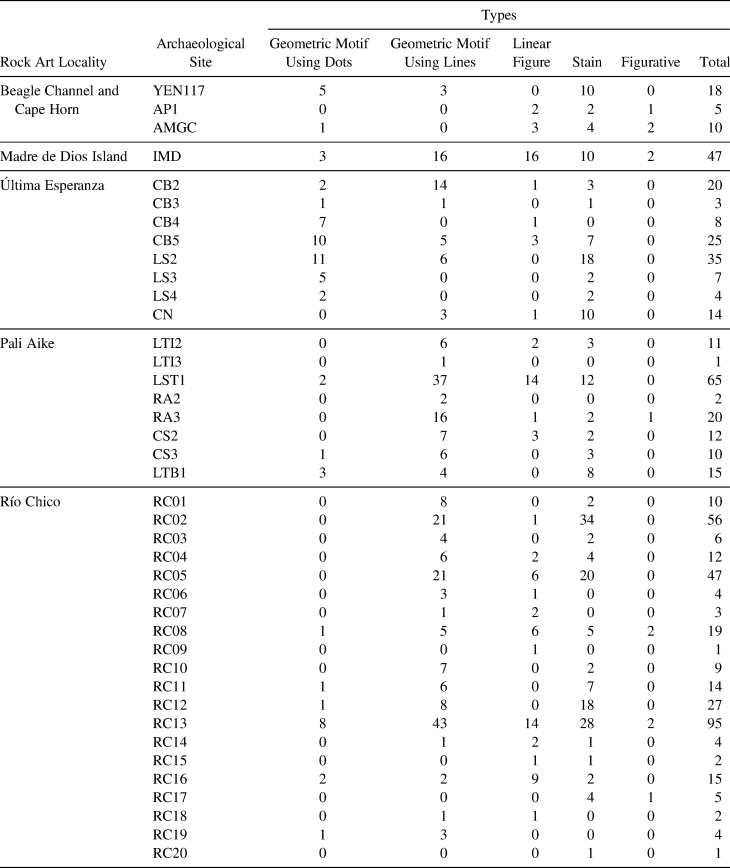

Table 1. Types of Motifs Presents in Each Locality by Archaeological Site.

It is interesting to note that the placement of some motifs shows interaction with the surface of the support: thus, we see that a series of dots forms a continuous winding line that cuts precisely over one of the natural horizontal wavy lines formed by the layers of the rock (Figure 4a). In contrast, a series of parallel vertical lines is placed on a very flat portion of the support, emphasizing the straightness of those strokes (Figure 4b).

The Rock Art of Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia at the Southern Tip of the Americas

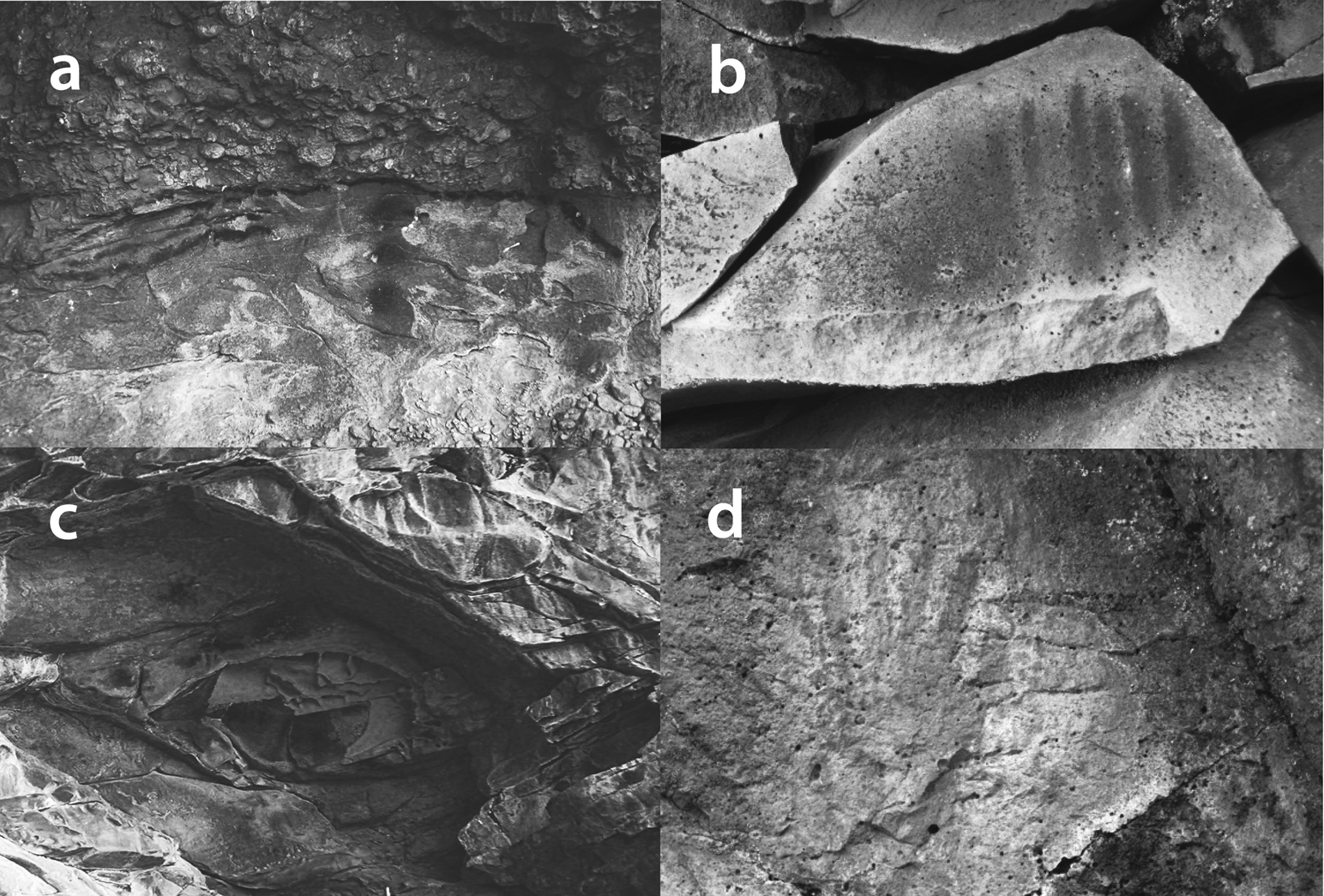

Since the first rock art studies were conducted in the 1970s, the sites identified in Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia have increased in number and distribution (Bate Reference Bate1970, Reference Bate1971; González et al. Reference González, Gañán and Serrano2014; Jaillet et al. Reference Jaillet, Fage, Maire and Tourte2010; Legoupil and Prieto Reference Legoupil and Prieto1991; Massone Reference Massone1982, Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Cordero and Artigas2016; Sepúlveda Reference Sepúlveda2011). At numerous sites in Última Esperanza and Pali Aike, Massone and colleagues carried out the first systematized study of motif types and their quantitative distribution. Given the importance and scope of this investigation, we use his definitions and findings for rock art sites and units. His typology is comprehensive and enables the comparative regional approach proposed here. Massone (Reference Massone1982) identified (1) geometric motifs based on dots (a single dot, an unorganized group of dots, a series of dots in a line); (2) geometric motifs based on strokes (one alone, two parallel lines, a series of parallel strokes, divergent lines, irregular strokes); (3) linear figures (classified as closed, complex, or both by the author, including circular and quadrangular motifs, linear ones with appendices, reticulated ones, and irregular linear figures); and (4) stains of paint (paint added intentionally to a panel with no defined shape; Figure 5). We also distinguish “figurative” motifs as either human or animal representations, including negative and positive handprints (only the latter corresponded to a fifth category of Massone; Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Examples of the categories used for the analysis: (a) lineal figure (top) and geometric motif using dots (bottom; CB5, Última Esperanza); (b) geometric motif using lines (RC08, Río Chico); (c) paint stains (CN, Última Esperanza); and (d) figurative motifs (RC17, Río Chico).

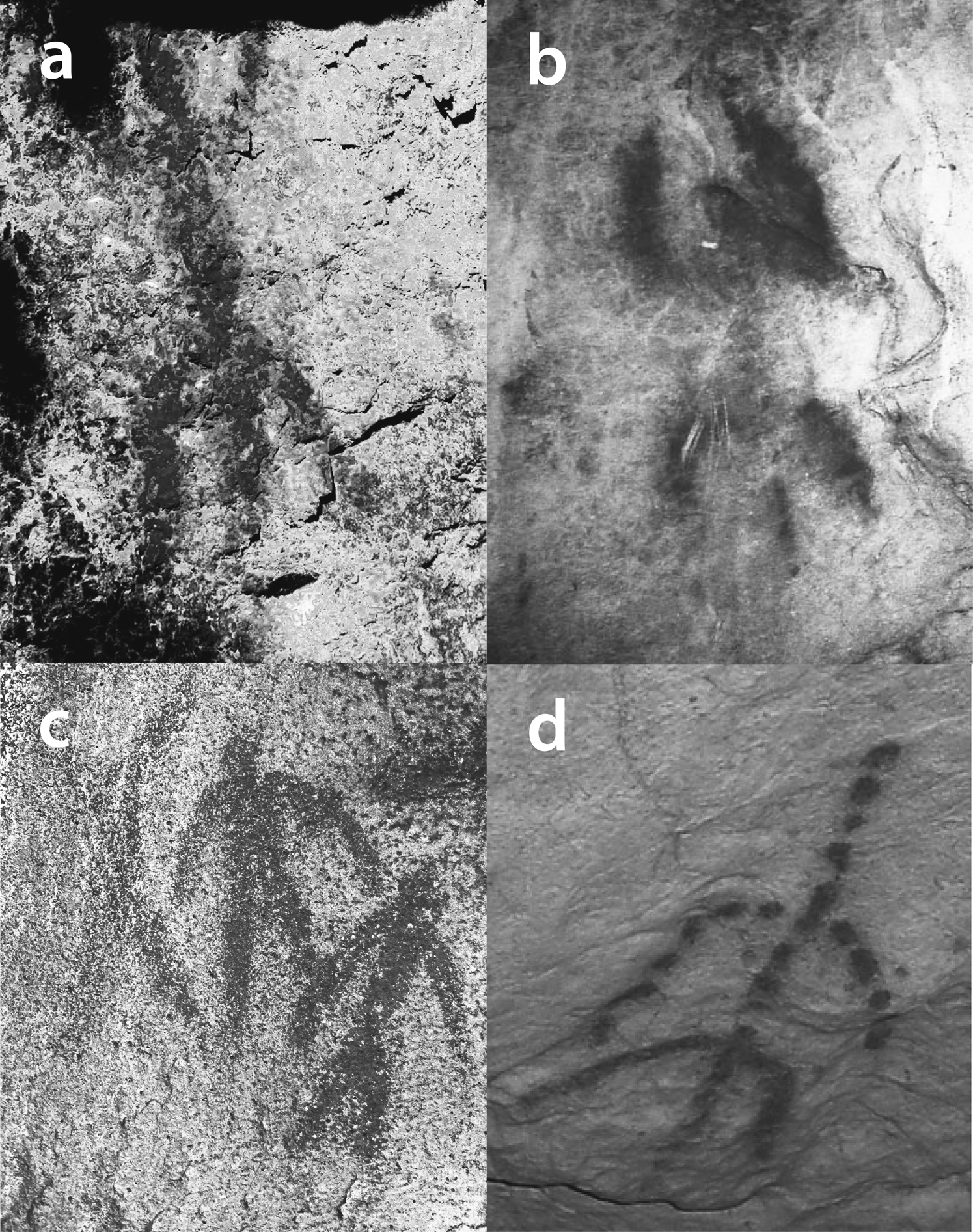

Figure 6. Examples of anthropomorphic figures: (a) AMGC, Beagle Channel, and Cape Horn (González et al. Reference González, Gañán and Serrano2014: Figure 4); (b) Madre de Dios Island; (c) RC08, Río Chico; and (d) Madre de Dios Island.

This comparative study includes rock art localities in the Tierra del Fuego archipelago-Beagle Channel and Cape Horn (territory traditionally occupied by the Yagán people), Madre de Dios Island (territory traditionally occupied by the Kawashkar people), and localities on the mainland (the southern tip of Patagonia); Última Esperanza; and the volcanic field of Pali Aike, where the canoe-faring people and the Aonikenk lived in historic times.

Beagle Channel and Cape Horn: Picton 1 and Martín González Calderón Shelter

At the Picton 1 shelter site (AP1), which is located on the southwestern coast of the island with the same name (Figure 1), Muñoz and collaborators (Reference Muñoz, Cordero and Artigas2016) recorded three motifs in red paint. In their illustrations, at least two stains of paint can also be observed (Table 1). The motifs are exclusively linear figures organized along a main line. In one case, the main line is horizontal, and there are five parallel vertical strokes emanating from it (or in horizontal transition). In the lower segment, the authors indicate the possible presence of an orange-hued stencil. In the other two motifs, the axis is a straight vertical line with shorter, oblique lines on either side, which in one case are replicated at opposing angles—forming a diamond shape; in the other, the lines are replicated at the same angle, forming a somewhat anthropomorphic shape. The authors interpret both cases as human representations, in comparison to other motifs painted at sites in the Tierra del Fuego region.

At the Martín González Calderón rockshelter (AMGC) located at Šapinij (Shapine) Island in Ponsonby Sound (Figure 1), González and colleagues (Reference González, Gañán and Serrano2014) note the presence of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic paintings, a variety of separate linear strokes of varying thicknesses (linear figures), and areas covered in red paint (stains; Table 1). According to these authors, red is the principal color of paint used, although they also mention some motifs in white, including linear strokes that form a quadrangular figure and a possible anthropomorph (closed or open linear motifs). In both cases, most of the motifs have been created through continuous graphic solutions in which the stroke extends uninterruptedly to form the figure.

Madre de Dios Island: Cueva del Pacífico

Jaillet and coworkers (Reference Jaillet, Fage, Maire and Tourte2010), during their speleological exploration of a large limestone cavern on Madre de Dios Island (IMD), discovered some rock paintings. In the “Cueva del Pacífico,” so named by its discoverers, 45 motifs were recorded: 26 were in red paint, occupying the upper part of the walls (from 4 m to 50 cm), whereas the 19 remaining motifs were black and were located lower down (no higher than 70 cm above the floor). The authors confirm the preponderance of anthropomorphic representations (N = 11), with “fewer” geometric shapes (no numbers provided), such as “sun wheels” or “nets,” and two zoomorphic motifs identified as marine mammals and some dates and letters, which would be consistent with the site's continuous occupation for some 4,000 years. Based on these descriptions, closed and open linear figures seemed to recur most frequently. However, our records of the site show that motifs based on strokes and stains of paint are almost equally prevalent (Table 1). Paintings in red pigment are most notable in this repertoire, particularly in their design and execution that follow the norms seen at other sites. A significant number of images in black wood charcoal suggest later interventions within a different cultural framework than that of the oldest images; therefore, they are not considered in our analysis.

Whereas a vast variety of forms are displayed in these representations, it is possible to identify at least two modes of deploying strokes that produce different graphic solutions: continuous (the stroke extends without interruption to form the motif) and discontinuous (the figure is formed from intermittent strokes). These solutions of continuous/discontinuous strokes are independent of the type of motif being produced: either solution can be used to represent any type of motif.

Última Esperanza: Cerro Benítez, Lago Sofía, and Cueva de los Niños

The works of Laming-Emperaire (Reference Laming-Emperaire1959), Bate (Reference Bate1970, Reference Bate1971), and Massone (Reference Massone1982, Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985) provide descriptions of rock art painted in the locality of Última Esperanza, where red is the predominant pigment color used. The Lago Sofía modality is worth noting, because it offers motifs based on simple dots or dots in more complex groupings; strokes and linear motifs; and, in lesser quantities, thickly traced schematic zoomorphic figures and “ostrich tracks.” Massone (Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985) also notes the existence of another modality, Cerro Benítez, characterized by various types of strokes and linear forms that occasionally form complex motifs, as well as some anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures that are more schematic. A date of 2870 ± 65 BP (uncalibrated) was obtained from a stratum containing remains of the rock face of the CB2 site with traces of red colorant (Massone Reference Massone1982:87).

On the western shore of Última Esperanza Sound, there is a small rockshelter called Cueva de los Niños (“cave of the children”; CN), named for the remains of two infants found there. The grave goods include shell bead necklaces, fragments of sinews, feathers, painted leather, wood, and the remains of pigment (Legoupil and Prieto Reference Legoupil and Prieto1991; Legoupil et al. Reference Legoupil, Prieto and Sellier2004; Sellier Reference Sellier1999). These colorants were also used on the wall of the shelter, where extensive stains of paint can be observed; some of those stains were made up of “small droplets of paint” that were created using a blowing technique (Legoupil and Prieto Reference Legoupil and Prieto1991:135). Although the morphology of the motifs was not categorized, digital processing of the photographs to enhance contrast revealed some dots and lines that could have comprised discrete forms, now deteriorated. This funerary context was dated to 250 ± 50 BP (Legoupil et al. Reference Legoupil, Prieto and Sellier2004:226). Our analysis considers information from the four sites of Cerro Benítez (CB) and three at Lago Sofía (LS) published by Massone (Reference Massone1982), along with evidence from Cueva de los Niños (Table 1). In summary, in the Última Esperanza sector, the most prevalent motifs are those based on dots, strokes, and other linear figures that are composed without the use of symmetry (Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b).

Pali Aike Volcanic Field: Pali Aike and Río Chico

Pali Aike was studied by Massone (Reference Massone1981, Reference Massone1982, Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985) and collaborators. The sites there are located primarily in rockshelters that served as resting places: there are two sites at Laguna Timone (LTI), one in Laguna Sota (LST), two from Rose Aike (RA), two from Cañadón Seco (CS), and one in Laguna Los Tábanos (LTB; Table 1). Paintings are always red and rarely combined with yellow. The motifs are mainly parallel traces in different sequences or that form geometric figures. Finally, intentional stains are frequent.

Massone (Reference Massone1982) relates this rock art to the Río Chico modality defined by Bate (Reference Bate1970, Reference Bate1971) based on the archaeological sites of Ush Aike (or Oosin Aike), Cueva Fell and Río Chico 1, 2, 5, 0, and Cañadón Seco 1 in this area—as well as Morro Chico and Cañadón La Leona found between the localities of Río Chico and Última Esperanza. Red is also the most used paint color, but combinations of black and white also can be found (Sepúlveda Reference Sepúlveda2011). This style modality is principally defined by series of lines varying in number and length, drawn in parallel or intersected by perpendicular lines, as well as some circles or squares with variated appendixes. There are also exceptional cases of schematic anthropomorphic or zoomorphic figures and negative handprints. In short, these are simple geometric motifs with both regular and irregular shapes, with a predominance of motifs composed through the combination of simple elements based on short and long strokes. These elements were arranged symmetrically, with movements that include reflection, one-dimensional translation, and two-dimensional rotation, with the last type of movement being most common (Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b).

For this analysis we consider our own records (Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b; Sepúlveda Reference Sepúlveda2011) from 20 rock art sites in and around Río Chico (RC01-20), including Fell Cave (RC11), and the data published by Massone (Reference Massone1982) for the Chilean side of the Pali Aike Volcanic Field mentioned earlier (Table 1). A reconnaissance conducted by Bate (Reference Bate1971:35) in one of the shelters with cave paintings in Río Chico (RC08 in our nomenclature) found a deposit that included stone instruments, characteristic of Period IV (Bird Reference Bird1946); guanaco bones; and a piece of red pigment associated with a stove that was dated to 2080 ± 80 years BP. A date that may represent the beginning of the rock art chronology, given the continuity of the settlement pattern, should for now be extended to at least Period V or the early historic period.

Yendegaia: Rock Art and Social Interaction in Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia

Handprints, guanacos, hunting scenes, footprints, and geometric figures are all frequent rock art motifs in central and south-central Patagonia (e.g., Acevedo and Fiore Reference Acevedo and Fiore2020; Gradin Reference Gradin1988; Guichon and Re Reference Guichon and Re2020; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Re, Cordero, Guichón and Artigas2021). However, these designs decline in variety and frequency as one moves across Patagonia and toward the Strait of Magellan. The southernmost records are found around Última Esperanza, near Torres del Paine, and in the Pali Aike Volcanic Field (Bate Reference Bate1970, Reference Bate1971; Charlin Reference Charlin2014; Gómez Reference Gómez Otero1993; Hernández et al. Reference Llosas, Isabel, Nami and Woroszylo1999; Manzi and Carballo Reference Manzi and Marina2012; Massone Reference Massone1982, Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020). These rock art sites, which are distributed from the southern tip of the continent to Cape Horn in the south and Madre de Dios Island in the west, display a spatial distribution that reveals differences between the territories of canoe-faring and land-based hunter-gatherers.

A simple numerical and percentage examination of the motifs in these Patagonian territories indicates the presence of a narrow corpus of shared visual solutions, with differing frequencies that distinguish one locality from another (Table 2). These differences are evident in the percentage distribution of motif types, especially dots in the archipelago and strokes on the mainland; yet the procedures used to create structural symmetry such as translation, which gives rise to sequences of motifs, are the same across all localities (see Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b). Another trend is the preferential use of red compared to other colors. In rock art expressions, the relative scarcity of figurative motifs (those with an identifiable point of reference) is another common feature. It is also noteworthy that designs with human attributes display tremendous formal similarity among sites from the Beagle Channel to Madre de Dios Island (Figure 6). The spreading of paint-forming stains covering large areas of the rocky walls, as observed at Cueva de Los Niños (Legoupil and Prieto Reference Legoupil and Prieto1991), is also common. This practice may have had more than a visual purpose: although all rock art operates on the visual plane, it also operates in relation to the place where the art is situated, so that the creator engages in a dialogue with both the paint and the rock support. These large stains of paint, and the exceptional expenditure they represent, could be classed broadly as acts of offering, like the practices of painting the bodies of the dead and their tombs (e.g., Prieto et al. Reference Prieto, Morano, Cárdenas, Sierpe, Calas, Christensen and Lefevre2020).

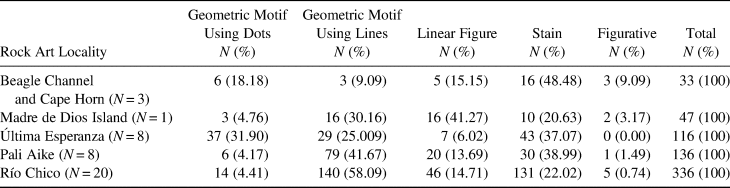

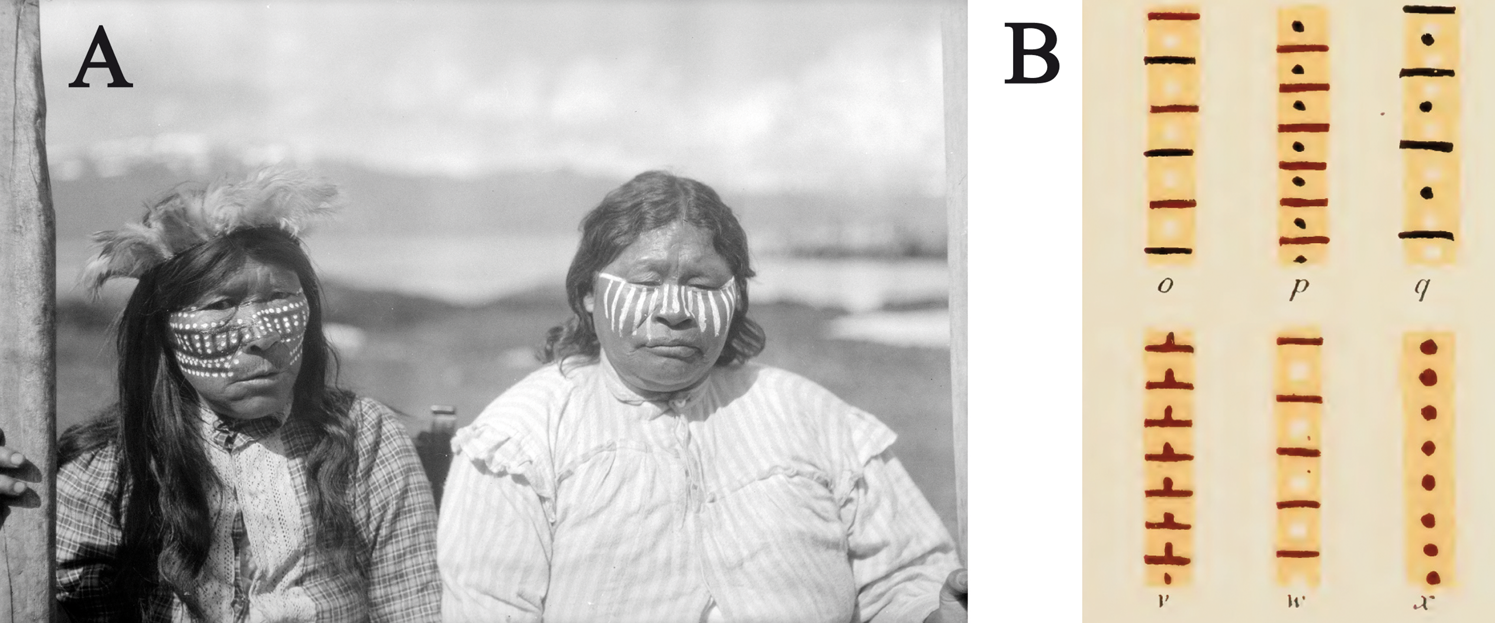

Table 2. Frequency of Motif Types for Each Locality Analyzed.

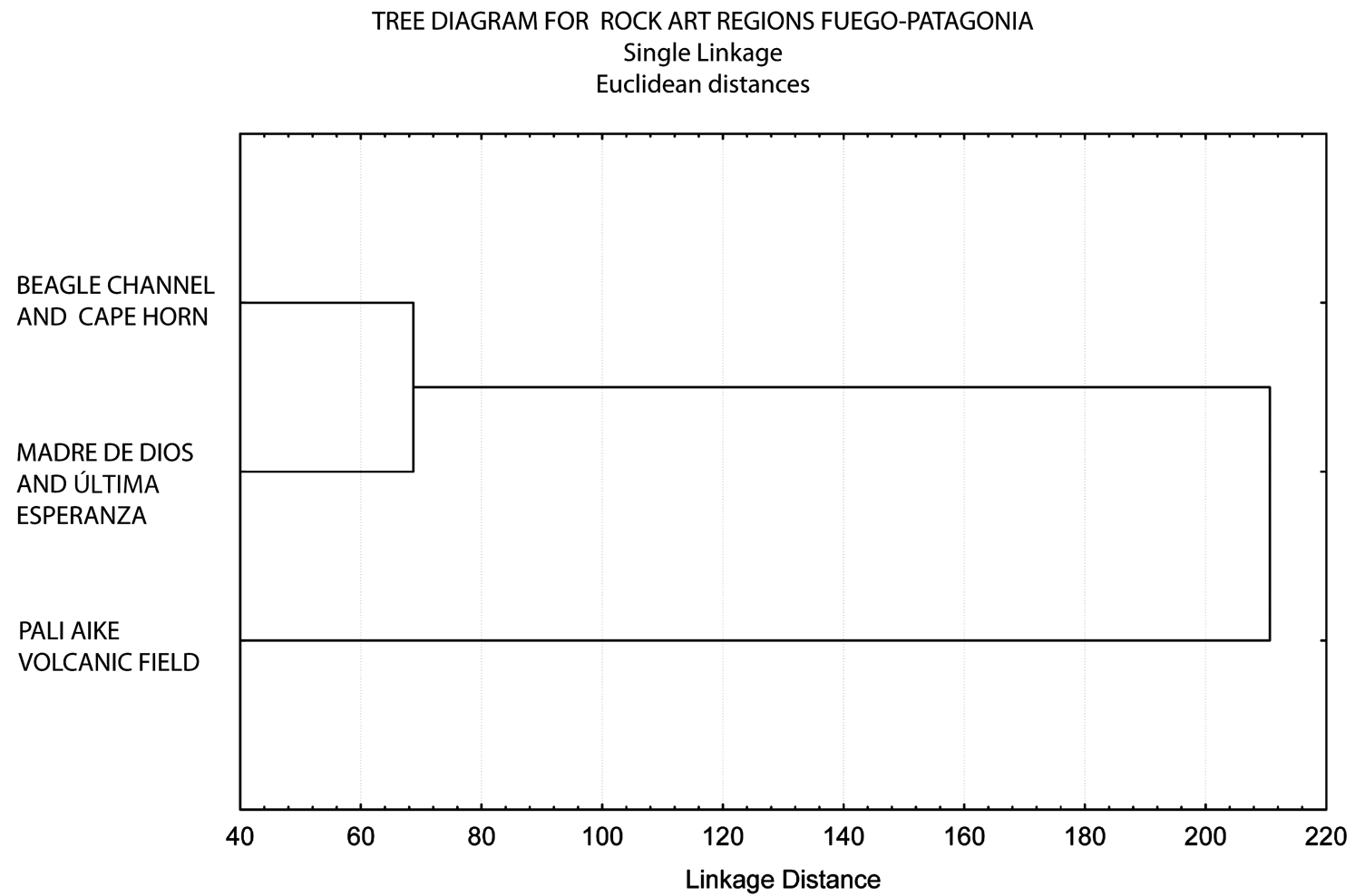

Given the quantitative similarities and differences observed (Tables 1 and 2), we applied a comparative analysis among the localities studied. We analyzed cluster groups (using Euclidean distances) to measure the geometric distance between cases in a multidimensional space (single linkage). However, because each locality displayed singularities influenced by the distribution of rock art at each site, we grouped them in relation to territories associated with the Indigenous peoples of Patagonia-Tierra del Fuego: Magallanes archipelago (Madre de Dios Island and Última Esperanza), the ancestral territory of the Kawashkar people; the Pali Aike volcanic field (Río Chico and Pali Aike), the ancestral territory of the Aonikenk people; and the Beagle Channel-Cape Horn, the traditional territory of the Yagán people (Table 3; Figures 1 and 7).

Figure 7. Cluster analysis on rock art paintings and groups from the Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia region.

Table 3. Types of Rock Art Motifs, Grouped by Traditional Cultural Territories.

Despite their broad geographic range, our results reinforce trends observed previously, suggesting that there are differences between the rock art associated with marine hunter-gatherers and that associated with land-based hunter-gatherers (Charlin and Borrero Reference Charlin, Borrero, McDonald and Veth2012; Massone Reference Massone1982, Reference Massone, Aldunate, Berenguer and Castro1985; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020). Even though previous efforts did not include information on the rock art of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, it is now evident that the rock art imagery of the territories belonging to the canoe-faring people (home to both the Kawashkar and Yagán peoples) also exhibits differences from both types of hunter-gatherers. Certainly, it is likely that the distance between the Magallanes Archipelago and the Beagle Channel-Cape Horn areas would have led to distinctions between the two traditions (Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020:173).

Despite the quantitative differences, the similarities in motifs, their graphic solutions, limited variety, and the predominant use of the color red reveal flows of visual information in a vast spatial scale, which is consistent with the widespread use of seagoing vessels among all the agents and the regular circulation of goods, ideas, and people over long distances. The results of this analysis also suggest that the rock art produced in the territory of the land-based hunter-gatherers of Pali Aike would not have been implicated in the same interactions established between canoe-faring peoples.

Visual Practices and Pigment Uses in Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia

The production and circulation of visual material culture by the Indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego go back to early times, as evidenced by portable bone art dated to at least as early as 6400 BP (e.g., the Túnel I and Imiwaia I sites in the Beagle Channel region; Fiore Reference Fiore2011). The corpus of decorative designs on portable bone art is strictly geometric and reveals the use of one or more basic elements, sometimes in specific combinations: straight or curved lines, curved and straight-lined figures, and series of dots and dashes arranged in a line or in groups (Fiore Reference Fiore2011). By combining these basic elements, their creators crafted numerous designs that display a wide variability and were used in the decoration of instrumental artifacts, such as harpoon points or staffs, as well as unworked bone pieces. In contrast, the decoration on ornamental beads focused on the use of parallel dashes in series and on parallel straight lines in series that encircled the perimeter of the pieces to form highly standardized designs. In contrast to the harpoon designs that were mostly produced from 6400 BP to approximately 4000 BP, these bead designs were produced throughout the archaeological sequence associated with the fishing-hunting-gathering peoples of the Beagle Channel (6400 BP to the nineteenth century), as well as on the neighboring island and mainland regions (Fiore Reference Fiore2006, Reference Fiore2020). This catalog of decorative designs is virtually the same as the rock art repertoire reported in this work.

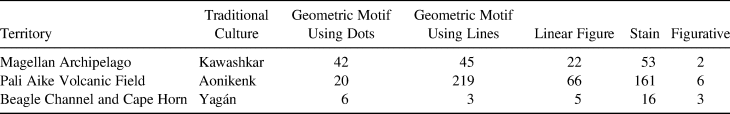

Documentary evidence also exists on the production and use of body paint among the Kawashkar people from the sixteenth century onward, among the Selk'nam from the sixteenth century onward, and among the Yagán from the seventeenth century onward (Fiore Reference Fiore2002, Reference Fiore2004, Reference Fiore2005). In the case of the Yagán, whose traditional territory includes the zone of Yendegaia, these painted designs used one or more types of decorative elements, including dashes, dots, lines, bands, “patches” of color (irregular shapes), rows of consecutive dashes, rows of parallel lines, and rows of dots (Fiore Reference Fiore2005). Members of Yagán society used body paint in a variety of contexts: in everyday situations (e.g., as expressions of mood, for visitors, for crossing channels, for collecting eggs, for recovering from illness, etc.); in special situations (e.g., at menarche, weddings, for mourning, by shamans, etc.); and in initiation ceremonies (chiéjaus, a male and female initiation ceremony, and kina, the male initiation ceremony; Fiore Reference Fiore2005, Reference Fiore2020; Figure 8a). Pigments were also applied to harpoons, grinding stones, paddles, hunting bows, and even formed designs in ceremonial lodges (Hyades and Deniker Reference Hyades and Deniker1891; Lothrop Reference Lothrop1928; Figure 8b).

Figure 8. Examples of Yagán decoration: (a) two Yagan women, Clara (left) and Anita (right), wearing facial paintings designed with parallel rows of dots and straight lines (identification of their names provided by the team of Museo Antropológico Martin Gusinde and Comunidad Yagán de Bahía Mejillones [Chile]; photo by M. Gusinde, 1922; copy held at the ARC-FOT-AIA [Archivo Fotográfico de Imágenes Etnográficas de Fuego-Patagonia, Asociación de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Buenos Aires, Argentina]); (b) selection of patterns of painted designs taken from the frame of a ceremonial lodge (from Lothrop Reference Lothrop1928:Plate IX). Note the similarity of the decorative elements used with those used in the rock art designs found at Yendegaia. (Color online)

This evidence leads us to suggest that, in the production of these varied types of art, there were at least two visual codes operating at different times in the history of these fisher-hunter-gatherers of southern Tierra del Fuego. Although these visual codes were deployed in very different media—artifacts and human bodies—it is essential to note that in both media the designs were structured around combinations of simple geometric elements: dashes, lines, dots, and simple figures—with the first three of these coinciding with design elements also observed in the rock paintings found at Yendegaia.

Furthermore, archaeology in the region also offers information about how different hues of red pigment—along with yellow and black in different contexts—were produced from similar raw materials. An in situ analysis of rock paintings on Madre de Dios Island indicates the use of iron oxide and charcoal (Jaillet et al. Reference Jaillet, Fage, Maire and Tourte2010; Maire et al. Reference Maire, Tourte, Jaillet, Despain, Leans, Brehier, Fage and White2009). Similar pigments have also been discovered from early dates at the Tunel I, Shamakush I, and Imiwaia I sites in Tierra del Fuego and at the Offing 2 site on Dawson Island in the Strait of Magellan. These come from layers dated between 6200 and 154 BP, demonstrating that the Indigenous inhabitants of this area had a long tradition of managing mineral colorants and organic binders in producing paints (Fiore et al. Reference Fiore, Maier, Parera, Orquera and Piana2008; Sepúlveda et al. Reference Sepúlveda, Gutiérrez, Cárcamo and Legoupil2022). In this sense, the information confirms the existence of paint production techniques that serve as additional evidence for the presence of painted rock art production technology. They show that knowledge and practices for managing color were available early in the region and were shared in different contexts by these canoe-faring groups.

Conclusion

The new discovery of rock art in the south of Isla Grande in Tierra del Fuego and its links with rock art from the Beagle Channel–Cape Horn region enabled us to undertake this comparative exploration of these visual expressions of southernmost Patagonia. Although the chronology of rock art at the southern tip of the Americas is still a work in progress (Brook et al. Reference Brook, Franco, Cherkinsky, Acevedo, Fiore, Pope, Weimar, Neher, Evans and Salguero2018; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2020; Sepúlveda Reference Sepúlveda2011), the close similarities established in this limited graphic corpus suggest that information was flowing primarily among the canoe-faring peoples, who probably left their rock testimonials after what Bird (Reference Bird1946) has named Period IV, between approximately 4500 and 900 BP (Massone Reference Massone1981). Furthermore, the numerous rock art sites that postdate 2000 BP in the Pali Aike Volcanic Field and the corresponding stylistic similarities with sites found elsewhere in the region point to the relative contemporaneity of the rock art localities included in this study (e.g., Bate Reference Bate1978–1979; Gallardo Reference Gallardo2009b; Laming-Emperaire Reference Laming-Emperaire1959; Massone Reference Massone1981). Although it is not possible to specify the chronology of the paintings we presented in this article, the available information indicates that they were being produced until the eighteenth century: a time when paint thrown on the rocky support may have been more common than the production of motifs, as in Cueva de los Niños. It is premature to associate stylistic patterns with temporal value, however; given the few iconographic variations and cave practices in Fuego-Patagonia, we suggest that these flows of visual information were of importance until the early historic period.

The flows of rock art information revealed here are also consistent with the visual information recorded on other supports, such as bone artifacts, ceremonial lodges, and body painting. Social interactions among the peoples of southern Patagonia were mediated by a diverse series of visual cultural strategies. For example, a brief record left by Duplessis (Reference Duplessis2003), written in the late seventeenth century, describes an incursion into the Jerónimo Channel (between Riesco Island and the Brunswick Peninsula), during which a group of naval officers were amazed to see a rocky wall painted entirely in white, near a hut made of fine skins, which contained a deceased child. This action at the level of the visible and the social was likely an expression of mourning that paid homage to an untimely death.

Social interactions were not foreign to those who inhabited Tierra del Fuego Island and the surrounding archipelago; indeed, historic and ethnographic sources confirm their normal and regular occurrences (e.g., Cooper Reference Cooper1917). This environment of social interaction would have involved intercultural relations that would also have fostered the circulation of technologies and goods, such as green obsidian, iron pyrite for fire starting, and marine and terrestrial resources (e.g., Borrero et al. Reference Borrero, Martín, Barberena, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011; Fiore Reference Fiore2006; Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Ballester, Prieto, Sepúlveda, Gibbons, Gutiérrez and Cárcamo2018; Morello et al. Reference Morello, Stern and Román2015). There is little doubt that the rock art of the southern Patagonia Archipelago and the nearby mainland, with their rugged, windswept lands lashed by rain and snow, encouraged the forging of intercultural social bonds that—based on the evidence of contact between territories—allow us to infer an aspiration for cooperation rather than competition. Creating a network of social complementarity in which social information flowed probably made it possible to reduce survival risks associated with low-population density groups that were separated by long distances.

Acknowledgments

We thank those who enabled and supported our field study at Yendegaia: Ernesto Davis Seguic, investigator, and Paola Acuña Gómez, executive director of Fundación CEQUA; Francisco Cornejo Alarcón, chief unit engineer, MOP-CMT, Dirección de Vialidad MOP; and Israel Pardo Román, Dirección Regional de Vialidad, Magallanes, and the Chilean Antarctic Region. Special gratitude to Luna Marticorena Galleguillos, Museo Antropológico Martin Gusinde, and Comunidad Yagán de Bahía Mejillones. We also thank Joan Donaghey for the English translation and Christina Torres-Rouff for proofreading. Finally, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions, which helped improve the article. Except where otherwise noted, all figures are courtesy of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

All data in this article are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.