Dementia is now one of the leading causes of disability among older people (Mental Health Foundation, 2015; World Health Organization, 2017) because it triggers a cognitive impairment that often results in increasing dependency on others. The care for a person with dementia is normally provided by family caregivers who do not receive any economic recognition in exchange (Vitaliano et al., Reference Vitaliano, Zhang and Scanlan2003). Most previous (quantitative) research on this topic has highlighted the various ways in which caregivers can evaluate the physical, emotional, social and/or financial burdens of their situation (e.g., Buyck et al., Reference Buyck, Bonnaud, Boumendil, Andrieu, Bonenfant, Goldberg, Zins and Ankri2011), although some work has also been done on positive aspects of caregiving (e.g., Netto et al., Reference Netto, Jenny and Philip2010; Quinn & Toms, Reference Quinn and Toms2019).

Subjective Burdens and Gains in Dementia Caregiving

Caregiving for a person with dementia is a chronically stressful situation since it requires copious physical and psychological efforts that frequently do not lead to the desired outcomes because of its high levels of unpredictability and uncontrollability (Schulz & Sherwood, Reference Schulz and Sherwood2008). This is why stress and coping theory (Lazarus & Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984) has been recognized and used as a valuable framework in many studies. This theory holds that individuals’ appraisals are a key element when they face a stressful event because they relate to the way they cope with that event and mediate its consequences. Indeed, many studies showed that caregivers who feel more burdened report lower levels of emotional well-being, mental health, and physical health (e.g., Chiao et al., Reference Chiao, Wu and Hsiao2015; Clyburn et al., Reference Clyburn, Stones, Hadjistavropoulos and Tuokko2000; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Knight and Longmire2007).

Despite its focus on the negative consequences of dementia caregiving, research has shown that many caregivers also identify positive aspects of caregiving (e.g., Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Mak, Lau, Ng and Lam2016; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Patterson and Muers2016; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Cheng and Wang2018), such as gains. Gains can be defined as “any positive affective or practical return that is experienced as a direct result of becoming a caregiver” (Kramer, Reference Kramer1997, p. 219). Examples of gains are developing personal qualities and practical skills, improving relationships with others, or acquiring deeper philosophical or spiritual insights into life, and they seem to be a common experience among caregivers, with over 80% of them ascribing at least one gain to their role (Netto et al., Reference Netto, Jenny and Philip2010; Peacock et al., Reference Peacock, Forbes, Markle-Reid, Hawranik, Morgan, Jansen, Leipert and Henderson2010; Sanders, Reference Sanders2005; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Luo, Ng, Chionh, Lim and Goh2010). Research has shown that the more gains caregivers experience, the lower their levels of negative affect, and the better their mental well-being (Liew et al., Reference Liew, Luo, Ng, Chionh, Goh and Yap2010; Rapp & Chao, Reference Rapp and Chao2010), which means that they may play an important role in promoting caregivers’ well-being.

These findings suggest that caregivers can find some benefits from stressful life events and even grow in the midst of adversity, and have led to new theoretical formulations explaining how caregivers can experience high levels of both subjective burdens and gains at the same time (e.g., Kramer, Reference Kramer1997; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Moss, Kleban, Glicksman and Rovine1991; Martire & Schulz, Reference Martire, Schulz, Baum, Revenson and Singer2000). According to them, rather than opposite ends of the same continuum, negative and positive aspects might be two independent dimensions with different predictors and/or consequences.

Caregiving Trajectories: Taking into Account Caregivers’ Temporal Perspectives

As previously stated, most research has studied caregivers’ current evaluations of their role using quantitative self-report measures, thus ignoring the temporal perspective of caregiving and missing some caregivers’ unique experiences that might be relevant for understanding both burdens and gains.

From a life course theory perspective, adults – at any age – make choices and get involved in multiple social roles, and thus, can experience changes that can be developmentally meaningful (Elder et al., Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003). Roles are “positions that individuals occupy within social institutions” (Macmillan & Copher, Reference Macmillan and Copher2005, p. 859), and occur during a period of time. The temporal involvement in a role, which can vary in duration across individuals, is referred to as trajectory. Thus, when a family member starts providing care to a relative with dementia, a transition is made into a caregiving role, and as long as this person continues to act as a caregiver, he or she will be construing his or her own caregiver trajectory.

Some authors have suggested that family caregivers of relatives with dementia might go through a similar set of phases. For instance, Schulz and Eden (Reference Schulz, Eden, Schulz and Eden2016) suggested that caregivers’ trajectories could typically begin with the awareness of the existence of a problem, which would be followed by the assumption of an increasing amount of responsibility and care demands, and lead to the last phase, consisting of end-of-life care provision. Alternatively, Kokorelias et al. (Reference Kokorelias, Gignac, Naglie, Rittenberg, MacKenzie, D’Souza and Cameron2020) identified five caregiving phases, namely, monitoring initial symptoms, navigating diagnosis, assisting with instrumental activities of daily living, assisting with basic activities of daily living, and preparing for the future. These approaches might be an undeniably useful resource to understand the caregiving role in a general manner, and to help designing interventions aimed at increasing caregivers’ well-being. Nevertheless, they seem to define caregiving trajectories based more on the progressive cognitive and functional decline of the care recipients due to the progression of the dementia (and their support needs and the responsibilities that caregivers must assume), than the individual perspective that each caregiver develops of his or her own experience, and so they do not recognize that each caregiving trajectory is unique. Yet, “the temporal dimension of caregiving is critical to establish the importance of caregiving in the life course of those needing care as well as those providing it” (Quan, 2021, p. 227).

The importance of such individual temporal perspective becomes even more evident when considering how caregivers’ perceptions of the development of their role since the illness begun might influence their evaluations of their current situation. For instance, coming to terms with the current caregiving situation may help caregivers to find meaning in caring for their relatives (Shim et al., Reference Shim, Barroso, Gilliss and Davis2013), and some caregivers might experience feelings of mastery after realizing that they have been able to cope with a past situation that they initially considered unmanageable (Sanders, Reference Sanders2005). Also, with regard to future expectations, caregivers’ pessimism about how the situation will change in the future has found to be a warning sign for poor current and future caregivers’ health and emotional well-being (Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Stewart, Archbold, Carter and Perrin2009). On the contrary, optimism has been associated to well-being and life satisfaction (Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Quinn, Nelis, Martyr, Rusted, Hindle, Longdon and Clare2019), considering that oneself is prepared to successfully manage the caregiving situation has been linked to a higher level of positive caregiving (Shyu et al., Reference Shyu, Yang, Huang, Kuo, Chen and Hsu2010), and having hope that a positive future is possible may encourage some caregivers to continue providing care to the relative with dementia (Duggleby et al., Reference Duggleby, Williams, Wright and Bollinger2009). Similarly, anticipating future losses and gains in the caregiving role has been associated, respectively, with a higher and a lower indecisiveness and unwillingness to provide care (Rohr & Lang, Reference Rohr and Lang2016).

Narrative Psychology might offer an alternative path to capturing the uniqueness of caregiving trajectories, since it allows to understand how people construct story plots in which their lived and expected events are interpreted and integrated (Brockmeier, Reference Brockmeier2000; Gergen & Gergen, Reference Gergen, Gergen and Abeles1987). These plots may reflect different trajectories, such as regressive (the main character loses developmental ground throughout the story), stable (the main character does not change much throughout the story), and progressive plots (the main character grows and expands throughout the story). In the same vein, McAdams and Guo (Reference McAdams and Guo2015) proposed a distinction between redemption plots, namely, story sequences that start with a negative experience that is followed by good or affectively positive outcomes, and contamination plots, which are characterized by the opposite pattern, the story starting well but ending badly. Recent studies suggest that redemption is positively and contamination is negatively related to psychological well-being (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Turner, Brookshier, Monahan, Walder-Biesanz, Harmeling, Albaugh, McAdams and Oltmanns2015; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Graham, Lauber and Lynch2019). As well as a movement from the past to the present, such life plots also include future expectations about how the self may evolve, which provide an evaluative and interpretive context for the current situation.

In summary, the importance of the temporal dimension of caregiving is reflected in the great amount of effort that has been made to understand the trajectory of dementia and how it changes over time. Nevertheless, so far research has fallen short of studying the trajectory of caregivers’ experiences (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Reference Gallagher-Thompson, Bilbrey, Apesoa-Varano, Ghatak, Kim and Cothran2020). Thus, there is a lack of studies gathering caregivers’ perspective on the past, present, and future of their role at the same time and trying to integrate them into different types of trajectories to study their relationship with both burden and gains.

Objectives

The present study has two goals. Firstly, we want to assess which meanings dementia caregivers attribute to their past, present, and future role as a caregiver. Secondly, we want to integrate such meanings into various caregiving trajectories and study their relation with caregivers’ burdens and gains.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Twenty-two organizations whose goal was to promote the well-being of family caregivers and their relatives with dementia were approached in Catalonia (Spain).

To standardize the data collection, one of the authors explained to the main person in charge of each association the purpose of this research and how to administer questionnaires. All organizations agreed to participate and appointed a staff member to make a list of all family caregivers who met the following criteria: (a) Currently caring for a person with dementia; (b) having been his or her caregiver for at least six months; (c) being one of the main caregivers with responsibility for making decisions concerning the person with dementia. The staff member was also responsible for approaching caregivers, briefly explaining to them the purpose of the study, and personally delivering the questionnaire. Questionnaires were self-administered.

In total, 417 family caregivers were approached and 278 returned the questionnaire. This represents a 66.7% response rate. We excluded 18 of them from the study because they did not meet the criteria mentioned above.

Measures

The questionnaire comprised three sections. Section one solicited sociodemographic information, including age, sex, marital status, relationship with the person with dementia, educational level, work status, religiosity, duration of the caregiving situation, and days per week and hours per day devoted to caregiving.

Section two included a sentence completion task eliciting experiences of the caregiver in a non-directive manner. Incomplete sentences consist of a sentence stem in the first person that respondents were asked to complete (more precisely, caregivers were asked to “Complete the following sentences with the first thing that comes to your mind”). Three sentence stems were used, focusing on the past (“When I started providing care to my relative…”), the present (“Nowadays, providing care to my relative…”), and the future (“In the future, providing care to my relative…”). Together, these sentence stems provide a subjective description of the trajectory that caregivers go through. Although not a narrative, the sentence completions allow for an analysis of the various trajectories from the past to the present and the future as perceived by individual caregivers.

Section three included the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) and the Gains Associated with Caregiving (GAC) scale. The ZBI is a 22-item self-report questionnaire that measures caregivers’ subjective feelings of burden (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Back-Peterson1980). We used the Spanish version of the ZBI, validated by Martín (Reference Martín1996). The internal consistency in the current study was found to be good (α = .89). Items are statements related to several feelings that caregivers can experience in relation to their role. Respondents have to indicate how often they feel a particular way using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to nearly always. Sumscores can vary between 0 and 88, so that the higher the score, the higher the level of burden,

The GAC scale is an instrument that measures gains among dementia caregivers (Fabà et al., Reference Fabà, Villar and Giuliani2017). Respondents judge whether they think that being a caregiver has helped them to experience 22 specific gains (e.g., “Being a caregiver has helped me to know myself better”), using a four-point response format ranging from not at all to yes, very much so. The GAC scale is a unidimensional measure that was developed in Spain, and it has a high internal consistency and concurrent validity. The internal consistency in the current study was found to be good (α = .94). Scores range from 0 to 66, so that the higher the score, the higher the amount of perceived gains.

ZBI and GAC scores did not significantly differ between caregivers who provided a complete trajectory and those who did not.

Data Analysis

We content-analyzed participants’ responses to the three incomplete sentences to identify common themes throughout them (Gubrium & Sankar, Reference Gubrium and Sankar1994). Content analysis involved four steps. We firstly became acquainted with the data by entering it into a database, reading and rereading it while trying to identify interesting ideas or units of meaning in participants’ responses. Secondly, we condensed these units of meaning into categories and subcategories based on both the repetition and the similarity among threads of meaning or key words, phrases, or sentences contained in the unit, and their level of abstraction (Owen, Reference Owen1984). This process produced a hierarchically organized category system for each incomplete sentence. Thirdly, a consensus between the three authors of this paper was reached about the label that best reflected the meaning of each category and subcategory. Disagreements during this process were identified and used to adjust the category limits, and their definition. As a final step, an external researcher coded the responses of 30 randomly chosen participants in each of the three category systems. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was .88 for the past situation, .85 for the present situation, and .93 for the future situation, thus indicating an almost perfect agreement between both categorizations (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

After establishing a category system for each incomplete question, we coded each subcategory in the three category systems as positive (P) or negative (N), depending on its implications. Since caregiver’ answers could sometimes allude to different components of their experience, and thus be coded into more than one category, when a caregiver’s response referred to both positive and negative categories at the same time (mixed answers), a consensus was reached on whether that response could be better coded as being primarily positive or negative (e.g., ‘Nowadays, providing care to my relative is such a pleasure, although it means forgoing a few things’ was coded as positive since we considered that the caregiver was describing the current situation as being globally pleasant, in spite of recognizing that caring was not without sacrifices).

Subsequently, we proceeded to identify, name and define different caregiving trajectories by seeking for distinct combinations of positive or negative responses to each of the three incomplete sentences, and we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the level of subjective burdens and gains among the trajectories, since both continuous variables presented a normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and Levene’s test suggested homogeneity of variances.

We used NVivo 2.0 software to analyze answers to the three incomplete sentences, and the SPSS 17.0 statistical package to perform the statistical analyses. Missing data in the items of the ZBI and GAC scales were imputed using the hot deck imputation method (Myers, Reference Myers2011), which replaces missing values with the score of another participant who is randomly chosen among all participants who match the receptor in a set of variables predetermined by the researcher (Andridge & Little, Reference Andridge and Little2010).

Ethical Considerations

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology of the first author’s university. Participants were volunteers who were provided with information about the objective of the study and the procedure to guarantee anonymity and confidentiality. Each participant had to sign an informed consent form before data collection.

Results

We excluded from the remainder of the study those caregivers who did not write a valid answer to one or more incomplete sentences. Thus, of the 260 participants who met the inclusion criteria, 63 were not included in further analyses because they did not provide a complete temporal trajectory. Differences in sociodemographic variables between them were studied. A Mann-Whitney test indicated that age was higher for the caregivers who did not provide a complete trajectory (U = 7,226.50, p < .05), and chi-square tests indicated that these caregivers were also more likely to be men (χ2[1] = 4.505, p < .05) and have lower educational levels (χ2[3] = 7.882, p < .01). No significant differences were recorded in the rest of the sociodemographic variables assessed between caregivers who provided a complete trajectory and those who did not.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the final sample of 197 caregivers. Caregivers’ age ranged between 31 and 91 years old, and participants were mainly married women caring for their spouse or one of their parents.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Past Meanings Associated with Caregiving

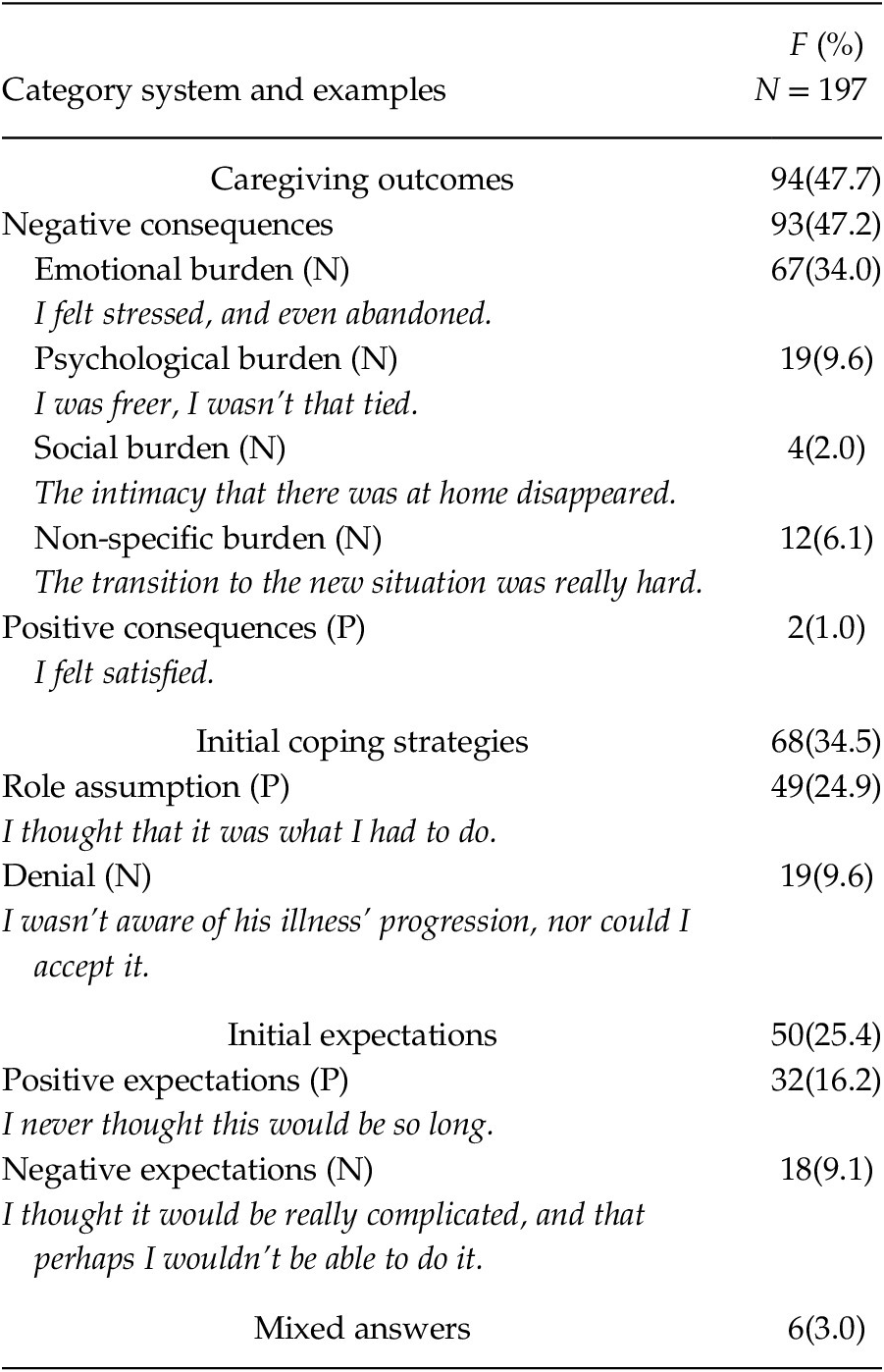

Table 2 provides an outline of the meanings that we identified for the sentence stem focusing on the past. The analysis of our data led to three main categories: Caregiving Outcomes, Initial Coping Strategies, and Initial Expectations.

Table 2. Frequencies (Percentages among Brackets) and Examples of Caregivers’ Answers to the First Incomplete Sentence (i.e., “When I Started Providing Care to My Relative…”)

Note. The sum of subordinate categories can sometimes be greater than their superordinate category because some participants’ answers included more than one reaction and, thus, were codified into more than one category. N = Category rated as negative evaluation; P = Category rated as positive evaluation.

The most frequently mentioned main category, Caregiving Outcomes, referred to the perceived implications of the role assumption. Caregivers mostly mentioned the subcategory of Negative Consequences, which included Emotional, Psychological, Social and Non-Specific Burden. Although we also identified Positive Consequences (all of them positive emotions), few caregivers referred to this subcategory.

The second main category, Initial Coping Strategies, had to do with caregivers’ reactions to their relative’s incipient deterioration and need for assistance. One subcategory was role Assumption (describing a prompt acceptance of the caregiving role). The other subcategory, Denial, refers to answers describing how caregivers initially ascribed their relative’s deterioration to a normal aging process, or how they never imagined –or even refused to accept– that he/she was living with dementia.

The final main category was Initial Expectations referring to caregivers’ past anticipations of their future. Most caregivers reported that they started out from Positive Expectations that mainly had to do with underestimating the required effort and sacrifices, or the illness’ length. We also identified some Negative Expectations, as some caregivers expressed doubts about their ability to cope effectively with the illness and its consequences.

Six caregivers provided a mixed answer to this incomplete sentence.

Present Meanings Associated with Caregiving

In the incomplete sentence referring to the present, we distinguished two main categories: Role Adaptation and Caregiving Outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequencies (Percentages among Brackets) and Examples of Caregivers’ Answers to the Second Incomplete Sentence (i.e., “Nowadays, Providing care to My Relative…”)

Note. The sum of subordinate categories can sometimes be greater than their superordinate category because some participants’ answers included more than one reaction and, thus, were codified into more than one category. N = Category rated as negative evaluation; P = Category rated as positive evaluation.

The most frequently cited main category, Role Adaptation, related to the degree to which caregivers had successfully accommodated themselves to the care provision situation. The most common subcategory was Adjustment, conveying that caregiving was an additional obligation or duty that caregivers had integrated into their everyday life. Caregivers seemed to have normalized their situation, which they often depicted as less burdensome or problematic, or easier to handle than previously. Some caregivers reported an opposing subcategory, Maladjustment (the caregiving situation being described as increasingly burdensome or more complicated).

As in the first incomplete sentence, caregivers also focused on the Caregiving Outcomes. Negative Consequences were again the most common subcategory, including Emotional, Psychological, Social, and Non-Specific Burdens. Caregivers reported Positive Consequences more often than in the first incomplete sentence, and they were also more diverse: Besides positive emotions (e.g., satisfaction, fulfillment), some caregivers described gains such as learning new things.

Seventeen caregivers provided a mixed answer to this incomplete sentence.

Future Meanings Associated with Caregiving

The sentence completions in the future-oriented incomplete sentence fell into two main categories: Expectations and Avoidance (Table 4).

Table 4. Frequencies (Percentages among Brackets) and Examples of Caregivers’ Answers to the Third Incomplete Sentence (i.e., “In the future, Providing Care to My Relative…”)

Note. The sum of subordinate categories can sometimes be greater than their superordinate category because some participants’ answers included more than one reaction and, thus, were codified into more than one category. N = Category rated as negative evaluation; P = Category rated as positive evaluation.

The most frequently cited main category, Expectations, consists of future anticipations. Most caregivers reported Positive Expectations. Role extension was, by far, the commonest type of positive expectation, and involved a commitment to future care provision even though some difficulties might arise. Institutionalization was an alternative to consider only in the worst possible scenario. Other caregivers stated that they expected the situation not to become worse or even improve (Equally or Less Challenging), or that they would like to continue experiencing positive emotions or gaining from their role in the future (Positive Consequences). The second subcategory was Negative Expectations, which included the occurrence of or increase in Negative Consequences and caregivers’ Doubts on Role Continuity (caregivers anticipating that they might not be able to continue providing care soon, either because of a further deterioration of the patient, or because of their own loss of autonomy, and presenting institutionalization as a realistic or probable option).

The second most frequently cited main category for the final incomplete sentence was Avoidance. Avoidance consisted of answers indicating that the caregivers focused on their day-to-day lives and had not –or were not willing to– reflect upon their future.

Seven caregivers provided a mixed answer to this incomplete sentence.

Trajectories and Their Relation to Caregiving Burdens and Gains

To analyze each participant’s answers to the three incomplete sentences as a whole, the subcategories for the past, present, and future situations were coded in terms of positive (P) or negative (N) evaluations. The final system consisted of six categories:

-

(1) Stable-negative trajectories (N-N-N; n = 27 [13.7% of the participants]). The prototypical stable-negative trajectory focused on negative consequences both in the past and in the present, and on future negative expectations (e.g., ‘I felt devastated – Is really stressful – Would be a torture’).

-

(2) Regressive trajectories (P-N-N or P-P-N; n = 36 [18.3% of the participants]) reflected a unidirectional movement from a positive past and/or present to a negative future. Mostly, initial positive expectations or reactions of role assumption led to negative consequences in the present and negative expectations about the future (e.g., ‘I thought I could resist it – Is psychologically impossible to me – I cannot even imagine it’).

-

(3) Present-enhancing trajectories (N-P-N; n = 42 [21.3% of the participants]) was characterized by a negative initial evaluation that turned into positive in the present, but that moved back to a negative future anticipation. These trajectories typically started focusing on past negative consequences and highlighted caregiver’s adjustment in the present, but the future was characterized by either negative expectations or avoidance (e.g., ‘I felt rushed and overwhelmed – I find it easier, as if the habit had become a routine – I don’t know if I can resist much more time’).

-

(4) Present-rejecting trajectories (P-N-P; n = 17 [8.6% of the participants]) started with a positive evaluation that turned into a negative one in the present to revert to a positive future expectation. In most cases, present-rejecting trajectories started with some positive consequences that were followed by present negative consequences that did not prevent the caregiver from holding positive expectations about the future (e.g., ‘I thought I can cope with it – Since the illness is progressing, the day-to-day is getting harder – I’m sure I’m going to be able to do it if I’m healthy’).

-

(5) Progressive trajectories (N-P-P or N-N-P; n = 52 [26.4% of the participants]) was the most frequently cited pattern, and it began with a negative evaluation that turned into a positive one in the present and/or in the future. More precisely, the prototypical progressive trajectory started with some negative consequences that were followed by the caregiver’s adjustment to the situation and that concluded with positive expectations about the future (e.g., ‘I felt overwhelmed and I didn’t know what to do – It has been integrated in my daily routine – I hope it’s going to be easier’).

-

(6) Stable-positive trajectories (P-P-P; n = 23 [11.7% of the participants]) included a positive sentence completion for each time frame. Usually, an initial reaction of role assumption had led to a present adjustment to the role, and positive expectations about the future (e.g., ‘I thought that it was what I had to do – Is not effortful if he’s calmed – I will continue doing my best until I can’).

We conducted a one-way ANOVA between-subjects to compare mean differences in burdens and gains among the six trajectories. As Table 5 shows, caregivers’ trajectories differed significantly on both variables. Post hoc comparisons using Tukey’s HSD test indicated that the mean burden was significantly higher for both regressive and stable-negative trajectories in comparison to both progressive and stable-positive trajectories. Caregivers with a present-enhancing trajectory were also significantly more burdened than caregivers reporting a stable-positive trajectory. In the case of gains, caregivers with a progressive trajectory reported significantly higher scores in comparison to stable-positive and regressive trajectories.

Table 5. Frequencies of Caregiving Trajectories and Results of the One-Way ANOVA in Burden and Gains

Note. Each subscript (a, b, c, d, e, f) corresponds to one of the six caregiving trajectories and are used to present statistically significant differences between groups according to Tukey’s HSD test (p < .05).

* p < .01

Trajectories were neither related to any of the sociodemographic variables included in the first section of the questionnaire, nor to the duration of the role or the time caregivers devoted to caregiving.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore caregivers’ meanings on their past, present, and future role, integrated them in caregiving trajectories, and studied their relation subjective burdens and gains.

Past, Present, and Future Meanings

When asked about their past, caregivers mainly talked about the caregiving outcomes and the negative consequences of starting to care for their relative (e.g., ‘I thought I wouldn’t be able to manage it, I was overwhelmed’). Most caregivers described role adaptation and successful adjustment in the present (e.g., ‘is more bearable since I go to an Alzheimer’s association and I feel understood by other people who are living a similar situation’) and positive expectations for the future (e.g., ‘will continue to be the most important thing to me, and I hope to press ahead with to the end’).

The positive and negative consequences in the past and present were comparable with those identified in previous research but did not exhaustively represent them. Emotional, psychological, and social burdens are reflected in the ZBI’s items (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Back-Peterson1980), whereas gains such as learning new things have also been identified in previous research (Netto et al., Reference Netto, Jenny and Philip2010; Peacock et al., Reference Peacock, Forbes, Markle-Reid, Hawranik, Morgan, Jansen, Leipert and Henderson2010; Sanders, Reference Sanders2005) and are included in the GAC scale (Fabà et al., Reference Fabà, Villar and Giuliani2017). Nevertheless, such research has also identified other types of burdens (e.g., physical and financial) and gains (e.g., gains in relationships) that did not appear in our study. Rather than contradicting previous research, our results might suggest that emotional and psychological burden might be the most relevant burdens in caregivers’ experience, and that gains might not be as salient as the negative consequences of caregiving and caregivers’ adjustment to their current situation, which appeared much more frequently than gains in the first and in the second incomplete sentences, respectively.

Although some caregivers had negative expectations, most of them were optimistic about their future. They had positive expectations, were committed to a continuation of their role, and considered institutionalization only as a last alternative (e.g., ‘is going to be harder, and I will probably need some help, but I wouldn’t like to place her into a nursing home’). As mentioned before, such optimistic beliefs relate to better health outcomes, whereas pessimistic beliefs might lead to the opposite results (Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Stewart, Archbold, Carter and Perrin2009; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Scheier and Greenhouse2009).

Trajectories and Their Relation with Burdens and Gains

The most important contribution of this paper to the previous literature is the study of perceived caregiving trajectories by combining caregivers’ reminiscences about their past, their evaluations of their current situation, and their anticipations of the future. Most importantly, five of the six trajectories showed associations with both burdens and gains, although the differences were larger for burden than for gains.

The present-enhancing and present-rejecting trajectories were characterized by a caregivers’ evaluation of their situation following opposed directions, and thus may be considered the less stable ones. This lower stability might make it more difficult for burden and gains to fully develop, which in turn may help to explain the fewer associations between them. Among these two trajectories, only the present-enhancing one was associated with higher levels of burden than the stable-positive trajectory. This difference may be attributed to the fact that, in the latter, positive evaluations seem to be a constant in time, whereas in the present-enhancing trajectory, an unfavorable past may have led to a fragile positive scenario that is not expected to last.

Furthermore, stable-positive and progressive trajectories were the most adaptive ones. Caregivers reporting these trajectories reported the lowest levels of burden. Nevertheless, progressive trajectories might be even more adaptive than stable-positive ones, because they showed higher levels of gains. Indeed, this might be the most striking result of our research.

Progressive trajectories begin with a negative evaluation of the past that turns into a positive one in the present and/or the future, so they might be similar to redemption sequences in story plots (McAdams & Guo, Reference McAdams and Guo2015). The difference between progressive and stable-positive in terms of gains suggests that some suffering at the beginning of the role might be necessary to experience higher levels of gains and benefit more from the caregiving experience. Thus, gains might be, to some extent, a comparable experience to posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004). However, the initial suffering might be a necessary but not a sufficient condition as present-enhancing trajectories did not show as much gains.

Similarly, ascribing a positive meaning to the future may have different implications depending on past and present evaluations of the caregiving role, as both stable-positive and progressive trajectories ended with a positive evaluation of the future, but the former did not show as much gains as the latter. This stresses the importance of integrating the meanings that caregivers ascribe to their past, present, and future instead of just focusing on one or two time frames. In the same vein, the regressive trajectory might be the most dysfunctional and maladaptive one because it was among the trajectories with most burdens and least gains. Considering that this trajectory starts with a positive evaluation of the situation that turns into a negative evaluation, the regressive trajectory might be comparable with McAdams and Guo’s (Reference McAdams and Guo2015) contamination sequence.

This research has some limitations. Firstly, our sample consisted of Spanish family dementia caregivers who were receiving some kind of formal assistance from organizations. Therefore, the results should not be generalized to other groups of caregivers, and further research focusing on people who do not receive formal assistance and in other countries is advisable. Secondly, we do not know if caregivers who volunteered to return the survey differed from caregivers who did not, although the demographic characteristics of the former met the prototypical dementia caregiver’s profile (e.g., Boerner et al., Reference Boerner, Schulz and Horowitz2004; Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Zarit and Pearlin2003). Thirdly, a considerable number of caregivers did not provide a valid answer to one or more incomplete sentences. The fact that incomplete trajectories were more common among older and less educated caregivers suggests that it might be more difficult for them to write down their own experiences. Although multiple choice questionnaires may be easier to fill out, they can suggest experiences that caregivers may not be thinking about, whilst the use of incomplete sentences is likely to be more spontaneous and capture more of what it is important to them. Fourthly, although in most cases participants reported one meaning per stem, arguably the most salient response (e.g., Nuttin, Reference Nuttin1985), more relevant meanings could be available if asked. The use of interview-based methods could have produced more complex and nuanced stories of caregiving. Fifthly, the study was cross-sectional, including caregivers with different temporal involvement in the caregiving roles, and used retrospective and prospective measures. Longitudinal studies could shed more light to the identification of different caregiving trajectories. Finally, there were no measures of problematic situations associated to the dementias, such as behavioral and psychological symptoms or family issues (e.g., conflicts), and how these variables could have an impact on the type of trajectory.

Despite these limitations, our study provides initial evidence that perceived trajectories do matter. Our findings reinforce the importance of gathering caregivers’ own points of view about their past and their future instead of only quantitatively assessing how they evaluate their present situation, or determining a unique set of phases that most caregivers are assumed to go through.

Caregiving trajectories might be a tool to gain deeper insight in the experience of dementia caregiving and the importance of caregiving from a developmental point of view, as well as a resource to consider when designing interventions to help caregivers reduce their burden levels and increase the benefits they ascribe to their experience. A possible strategy would be to help caregivers to reinterpret how they think about their own trajectories so that they become more adaptive. Similar to in life review interventions that combine reminiscence with present and future orientations (e.g., Korte et al., Reference Korte, Bohlmeijer, Cappeliez, Smit and Westerhof2012), caregivers who are building a more dysfunctional trajectory (and could be at a higher risk of suffering) may be stimulated to reinterpret their past and present situation and draw positive meanings and lessons out of dementia caregiving as well as to think positively about their future, thus turning stable-negative or regressive trajectories into progressive or stable-positive ones, respectively. Interventions aiming at encouraging caregivers to reappraise their past or current situation in positive ways have been proven to be effective at enhancing caregivers’ well-being (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chan and Lam2019). According to our results and to previous research (Duggleby et al., Reference Duggleby, Williams, Wright and Bollinger2009; Rohr & Lang, Reference Rohr and Lang2016; Shyu et al., Reference Shyu, Yang, Huang, Kuo, Chen and Hsu2010, they may become even more effective if specific efforts are made to positivize their future expectations.

This study also supports the need to adapt interventions to different profiles of caregivers since the beginning of the caregiving role. For example, those caregivers with more avoidant profiles may benefit of interventions aimed at training in acceptance (e.g., based in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, see Han et al., Reference Han, Yuen and Jenkins2021), while caregivers showing more adaptive profiles may benefit more from supportive interventions focused on maintaining the adaptive trajectory by decreasing potential sources of problems.