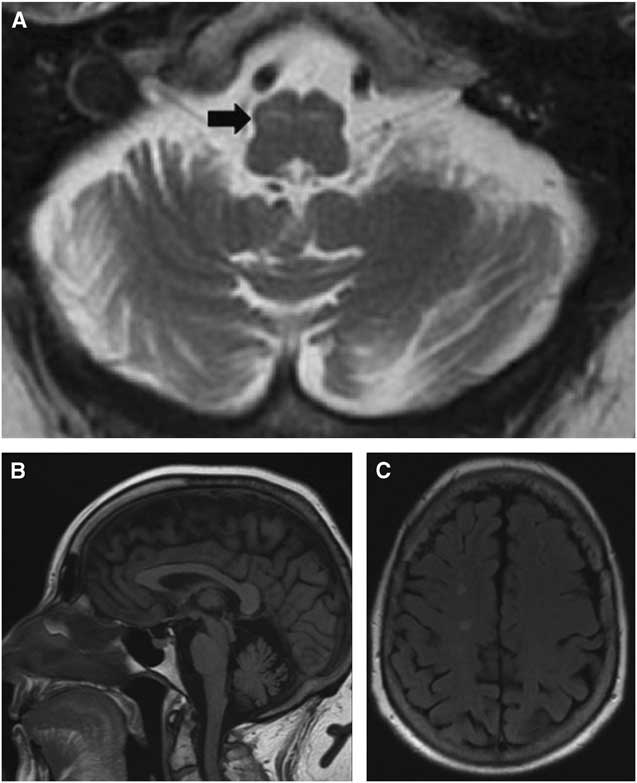

A 53-year-old woman presented to neurology with progressive imbalance, dysphagia, and clicking of her ears over two years. Two years prior to onset of neurologic symptoms, she developed a right breast mass followed by additional soft tissue masses composed of foamy histiocytes with fibrosis, leading to a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD), previously reported in detail.Reference Barnes, Foyle, Hache, Langley, Burrell and Juskevicius 1 Following pathology diagnosis, long-bone X-rays revealed typical diaphyseal and metaphyseal osteosclerosis.Reference Barnes, Foyle, Hache, Langley, Burrell and Juskevicius 1 She did not have diabetes insipidus. Peripheral blood BRAFV600E mutation was negative. Neurologic examination was remarkable only for palatal tremor (Video 1; see Supplementary Materials), symmetric limb ataxia, and ataxic gait. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated bilateral T2 hyperintensity of the inferior olivary nucleus (ION), moderate cerebellar atrophy, and several nonspecific T2 hyperintensities in the cerebral white matter without intracranial gadolinium enhancement (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Bilateral ION T2 hyperintensity (A, arrow) consistent with symptomatic palatal tremor associated with moderate cerebellar atrophy (B) and nonspecific cerebral white matter T2 hyperintensities (C).

ECD is a rare hematologic disorder of histiocytes with multifocal involvement, including skeletal (96%), retroperitoneal (68%), cardiac (64%), central nervous system (51%), orbital (25%), and hypophyseal (23%) manifestations.Reference Arnaud, Hervier and Neel 2 Among ECD patients with neurologic involvement, about 40% experience symptoms of a cerebellar syndrome with such features as ataxia, nystagmus, and dysarthria.Reference Lachenal, Cotton and Desmurs-Clavel 3 In this cohort of 66 ECD patients with neurologic manifestations, 45% exhibited pyramidal signs, while 47% had diabetes insipidus.Reference Lachenal, Cotton and Desmurs-Clavel 3 Neurologic symptoms may arise from extra-axial meningeal mass lesions or intra-axial infiltration. In a cohort with brain imaging, 44% had infiltrative cerebral lesions primarily in the brainstem and cerebellum, including within the Guillain–Mollaret triangle.Reference Lachenal, Cotton and Desmurs-Clavel 3

The Guillain–Mollaret triangle, or the dentato–rubro–olivary circuit, links the contralateral dentate nucleus with the ipsilateral red nucleus and the ION.Reference Murdoch, Shah and Jampana 4 Disruption of the circuit can be clinically associated with palatal tremor, ataxia, and ocular manifestations.Reference Murdoch, Shah and Jampana 4 Pathological causes include degenerative disorders (Alexander’s disease), infarction, demyelination, and trauma.Reference Goyal, Versnick and Tuite 5 Following damage to the Guillain–Mollaret triangle, ION T2 hyperintensity appears at approximately 1 month followed by ION hypertrophy at 6 months, which persists for 3–4 years, though T2 hyperintensity may remain indefinitely.Reference Goyal, Versnick and Tuite 5

We suspect that histiocytic infiltration of the structures composing the Guillain–Mollaret triangle resulted in ION radiographic changes and palatal tremor. Despite frequent infiltration of the brainstem and cerebellum, palatal tremor has not previously been described in ECD.

Disclosures

Natalie E. Parks and R. Allan Purdy hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

To view the supplementary materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2017.259.