Introduction

The timing of when humans arrived in South America, specifically north-western Patagonia (40°–44°S), is subject to ongoing debate and research. Archaeological evidence and palaeogenetic studies suggest human presence between 16 600 and 15 100 cal BP (Prates et al. Reference Prates, Politis and Perez2020). Sites such as Monte Verde I and II (Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay2015; Pino & Dillehay Reference Pino and Dillehay2023) and Pilauco (Pino & Astorga Reference Pino and Astorga2020) provide evidence of pre-Holocene human activity and extinct fauna during late Pleistocene–early Holocene transition.

Our team analysed lithic material from the Pilauco and Los Notros sites located in the Central Depression of the Lake Region in the city of Osorno, north-western Patagonia (Figure 1). The Pilauco site yielded about 200 artefacts dating between 17 300 and 12 800 cal BP (Figure 2). The initiative undertaken in 2022 represented an expansion of the original 2007 project spearheaded by Mario Pino with the objective being to enhance the characterisation of the lithic industry at Pilauco, assisted by 3D modelling and analysis (Pérez-Balarezo & González-Varas Reference Pérez-Balarezo and González-Varasin press).

Figure 1. Location of the Pilauco and Los Notros sites: a) southern cone of South America; b) north-western Patagonia; c) Osorno city (figure by Antonio Pérez-Balarezo; base maps from maps-for-free.com and Google Earth).

Figure 2. Revised pre-Younger Dryas chronocultural sequence at the Pilauco site. All the dates of the layers are calibrated years BP. The yellow star marks the position of the artefact 12PB-P120-220319 (figure by Mario Pino & Antonio Pérez-Balarezo).

The Pilauco site's organisation reflects a stratigraphic record that has been dated by 55 radiocarbon determinations and a Bayesian age model (Pino et al. Reference Pino2019, Reference Pino, Martel-Cea, Vega, Fritte, Soto-Bollmann, Pino and Astorga2020). The simple and well-preserved stratigraphy indicates minimal disturbance for about four millennia (Pérez-Balarezo et al. Reference Pérez-Balarezo, Navarro-Harris, Boëda and Pino2022). It comprises volcaniclastic and terrigenous sediments (PB-1 to PB-6) from regional volcanic activity. The floodplain includes PB-6's well-sorted gravel overlying the eroded PB-1. Above these, PB-7, PB-8 and PB-9 form horizontal strata, while PB-7 and PB-8 are peat layers containing gravel, which suggests an ox-bow swamp environment. Layer PB-7, covering PB-1 and PB-6, holds the most fossils and artefacts (Pino et al. Reference Pino, Martel-Cea, Vega, Fritte, Soto-Bollmann, Pino and Astorga2020). The gravel clasts, lacking percussion marks, point to a low-velocity depositional setting. The peat layer PB-9, free from fluvial inputs, seals the site. The most compelling evidence for the site's consistent age model and gradual sedimentation is the uninterrupted pollen record between PB-7 and PB-8 (Pino & Astorga Reference Pino and Astorga2020), which aligns with the site's stratigraphic integrity.

Comprehensive technological and petrographic study at the Pilauco site and new findings

The analysis conducted in 2022 was supposed to focus on the detailed study of the already known corpus of Pilauco. This lithic assemblage comprised 45 pieces, including cores (n = 15; 33%), worked pebbles (n = 2; 4%), flake tools (n = 12; 27%) and debitage products (n = 16; 36%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Notable lithic artefacts from Pilauco site layers PB-8 and PB-7, including choppers/cores (a–e) and flakes with multiple edges (b–d, f–h). Cutting edges are outlined in red. From PB-8 layer: a, b. From PB-7: c, d, e, f, g, h. (Sources: Pino et al. Reference Pino, Chávez-Hoffmeister, Navarro-Harris and Labarca2013; Navarro-Harris et al. Reference Navarro-Harris, Pino, Guzmán-Marín, Pino and Astorga2020) (figure by Antonio Pérez-Balarezo).

However, during our time at the site, we identified new artefacts in the stores of the Pilauco site museum that came from excavations carried out between 2008 and 2019. We identified 199 new lithics, adding to the 45 previously identified, to create a corpus of 244 artefacts, which are distributed among the layers PB-1/PB-7, PB-6, PB-7 and PB-8. The classification of these items as artefacts is based on their distinct features indicative of intentional flaking: presence of bulbar scars; aligned, overlapping and continuous flake scars on edges, forming clearly visible retouching; the absence of differential weathering of scars; identifiable dorsal and ventral surfaces; pronounced bulbs of percussion; and multiple dorsal flake scar count in some flakes.

The most common types of artefacts are the tools on pebbles and flakes (n = 91; 37%) (Figure 4, Figure 5a) and the flakes (n = 91; 37%), with the remainder being cores (n = 35; 14%) (Figure 5b), chunk (n = 10; 4%,), flake fragments (n = 6; 3%), anvils (n = 4; 2%), spheroids (n = 4; 2%) and manuports (n = 3; 1%). This collection is undergoing petro-mineralogical, technological, techno-structural, geometric morphological and use-wear analysis through 3D data.

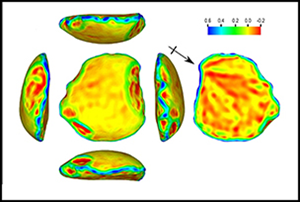

Figure 4. Lithic artefacts from the PB-7 layer of Pilauco site: A) transverse denticulate on a split pebble of porphyritic andesite; E) multiple cutting edges on a cortical pebble flake of aphanitic basalt, with cutting edges indicated by the red line; B–F) curvature analysis, highlighting worn areas and concavities; C–G) thickness analysis; D–H) cross-sectional and longitudinal sections in a 10mm2 grid. The double zoom images are variations of the colouring in B–F, but on a smaller scale (figure by Antonio Pérez-Balarezo).

Figure 5. Lithic artefacts from the PB-7 layer of Pilauco site: A) tool with a transverse cutting edge on a pebble flake of porphyritic andesite; F) exhausted core on porphyritic andesite, with cutting edges indicated by the red line; B–G) curvature analysis, highlighting worn areas and concavities; C) thickness analysis; D) cross-sectional and longitudinal sections in a 10mm2 grid. The double zoom images are variations of the colouring in B–F, but on a smaller scale (figure by Antonio Pérez-Balarezo).

Aphanitic basalt dominates the assemblage with 62 per cent, followed by various types of dacitic and rhyodacitic vitreous rocks and porphyritic andesites and trachytes, both groups with 19 per cent each. Only the vitreous rocks have their source about 80km to the east, in the vicinity of the Caulle volcano. All basalts, andesites and trachytes are available locally.

The 244 objects from Pilauco are in relatively good macroscopic surface condition. The cutting edges and ridges do not show any micro-flake negatives that could indicate significant post-depositional impacts. The Pilauco tools on pebbles and flakes are characterised by a close association between selection, flaking and retouch (Figure 6). In this sense, this toolkit does not differ from other contemporary assemblages recorded in Huaca Prieta (Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay2017), Arroyo Seco 2 (Politis et al. Reference Politis, Gutierrez, Rafuse and Blasi2016) and Monte Verde II (Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay2015).

Figure 6. Lithic artefacts from the PB-8 layer of Pilauco site: A) denticulate on a large flake of slightly vesicular aphanitic andesite; B) chopper-like artefact made on a pebble of aphanitic basalt, with cutting edges indicated by the red line; B–F) curvature analysis, highlighting worn areas and concavities; (C–G) thickness analysis; (D–H) cross-sectional and longitudinal sections in a 10mm2 grid. The double zoom images are variations of the colouring in B–F but on a smaller scale (figure by Antonio Pérez-Balarezo).

In terms of flaking methods, the corpus predominantly presents simple unipolar and bipolar cores flaked using the anvil technique. However, the presence of a core exhibiting a clear hierarchy between the striking platform and flake-release surface (Figure 4b) reveals an early technological adaptation of the human groups of Pilauco, which is rare for pre-Younger Dryas periods, around 16 000 cal BP.

Conclusions

The discovery of 200 lithic artefacts pre-dating the Younger Dryas period at the Pilauco site confirms recurrent human usage for over four millennia. This site is significant for understanding late Pleistocene occupation and tool-making behaviours in north-western Patagonia. Findings presented here substantiate the authors’ hypothesis that there was human occupation in the north-western Patagonian region at least 3000 years earlier than previously recognised.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fabiola Galleguillos for photographing the lithics and we thank the Osorno City Council, the Pilauco team and locals for their support.

Funding statement

This research was funded by ECOS-SUD-ANID (Evaluation-orientation de la COopération Scientifique-Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo) Action No. 200033. Francisco Tello was financially supported by Fondecyt de Iniciación a la Investigación-Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) grant 11220685. Antonio Pérez-Balarezo was financially supported by the Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR), Human paleoecology, Social and cultural Evolutions among first Settlements in Southern AMErica (SESAME) project ANR-20-CE03-0005. All authors were financially supported by the Foundation for Pleistocene Heritage Studies in Osorno, Chile (FEPPO). This work also received support from the Sorbonne Université Emergence Project: La tropicalité, un mode d’émergence et d'innovations culturelles (TROPEMIN).