Clinical and epidemiological studies have documented high rates of anxiety disorders among individuals with bipolar disorder (Reference MacKinnon, Zandi and CooperMcElroy et al, 2001; Reference Simon, Otto and WeissSimon et al, 2004b ). The impact of anxiety on the course of bipolar disorder has been less well delineated, but retrospective and cross-sectional studies suggest greater illness severity among patients with anxiety disorders (Reference MacKinnon, Zandi and CooperMcElroy et al, 2001; Reference Simon, Otto and WeissSimon et al, 2004b ), as well as poorer response to treatment (Reference GuyHenry et al, 2003). Prospective studies also indicate a detrimental role for panic-related anxiety symptoms on the outcome of bipolar disorder (Reference Feske, Frank and MallingerFeske et al, 2000; Reference Frank, Shear and RucciFrank et al, 2002). However, there is no large-scale, prospective study examining the impact of anxiety disorders defined by DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In this study we examined the association between anxiety disorders and bipolar course over a prospective 12-month period in patients at various stages of relapse and recovery at study onset.

METHOD

Study overview

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) is a multicentre study conducted in the USA, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and designed to evaluate the longitudinal outcome of patients with bipolar disorder (Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrichSachs et al, 2003). Participants were required to be at least 15 years old and to meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar disorder types I or II, cyclothymia, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder manic or bipolar subtypes. These study diagnoses were assigned only upon consensus following two structured diagnostic interviews. Exclusion criteria were limited, and included unwillingness or inability to comply with study assessments, or inability to provide written informed consent.

Participants

The sample consisted of the first 1000 patients (59% women) enrolled into STEP-BD. At study entry, participants had a mean age of 40.6 years (s.d.=12.7) and a mean duration of bipolar illness of 23.1 years (s.d.=12.9). The majority of the sample met DSM-IV criteria for primary bipolar I disorder (71%) or bipolar II disorder (24%). Of the 1000 participants, 4% met criteria for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified and 1% met criteria for schizoaffective, cyclothymic or unspecified disorder; these patients were excluded from analyses covarying bipolar subtype (I v. II).

At study entry, 39.8% of the sample were married or living as married, 82.3% had at least some college education and 47.0% had a college degree. Regarding occupational status, 34.5% reported full-time work outside the home, 20.0% reported part-time or homemaker status, 38.8% reported unemployment, disability or leave of absence, and 5.0% and 1.8% reported retired or ‘other’ status respectively. The majority of the sample were White (92.6%), with 3.4% of the sample identifying themselves as Black or African American, 1.1% Asian, 0.4% Native American or Alaskan and 2.8% as mixed race or ‘other’; 3.7% of the sample identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino.

Assessments and procedures

The Affective Disorder Evaluation (ADE; Reference Rotondo, Mazzanti and Dell'OssoSachs, 1990) includes a modified version of the mood and psychosis modules from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1997) intended for routine use by practising clinicians. The ADE also assesses age at onset of mood episodes, the number of prior episodes, periods of recovery, suicidal actions and past treatment response. A study psychiatrist completed the ADE with each patient at study entry; this served as the primary source of the history and characteristics of bipolar episodes and provided the basis for assigning bipolar status.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Plus Version 5.0; Reference Sachs, Thase and OttoSheehan et al, 1998) is a semi-structured interview designed to identify major Axis I psychiatric disorders, and was adapted to assess lifetime anxiety and eating disorders. In validation and reliability studies, the MINI was compared with the SCID Patient version for DSM-III-R and found to have acceptably high validation and reliability scores (Reference Sachs, Thase and OttoSheehan et al, 1998). In our study the MINI, administered by study clinicians, was used to confirm the bipolar-spectrum diagnosis and to identify comorbid psychiatric disorders at study entry.

The Clinical Monitoring Form (CMF; Reference SachsSachs et al, 2002) is a one-page assessment tool used by study clinicians to document the symptom and treatment characteristics of patients at each clinical visit. It consists of modified versions of the SCID current mood modules, associated symptoms, medical problems and comorbid conditions; selected mental status items; current medications adherence and adverse effects; laboratory data; summary scores narrative - i.e. clinical status, Clinical Global Impression - Severity (Reference Gaynes, Magruder and BurnsGuy, 1976) and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 1994: pp. 758-759) and treatment plan. To be certified in use of the CMF, treating psychiatrists completed standardised training and met certification requirements for establishing interrater agreement with video-taped ratings. Once certified, treating psychiatrists were periodically monitored to help maintain rating standards (Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrichSachs et al, 2003). The CMF was the primary source of clinical status information.

On the basis of the presence or absence of criteria based on DSM-IV, one of eight operationally defined clinical states was assigned at each clinic visit. Four clinical states corresponded to the DSM-IV definitions of major depression, mania, hypomania and mixed episodes. Patients achieving relative euthymia (up to two moderate symptoms) for at least a week were assigned a status of ‘recovering’ or ‘recovered’, depending on whether this status had been sustained for at least 8 weeks. Two sub-syndromal states categorised patients as either ‘continued symptomatic’ or ‘roughening’. These bipolar state categories and reliability training are further discussed by Sachs et al (Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrich2003).

Quality of life and functional impairment were assessed with two scales. The short form of the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q; Reference Endicott, Nee and HarrisonEndicott et al, 1993) is a 16-item self-report questionnaire assessing the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction in a variety of areas of daily functioning. Higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. Functional impairment was assessed by the clinician-rated Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation - Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT; Reference Kolodziej, Griffin and NajavitsLeon et al, 2000), with higher scores indicating greater impairment.

Assigment of clinical status during prospective study

Although the CMF served as the primary source of clinical status information for patients in the longitudinal phase of the study, other sources of information were included in the assignment of ‘estimated days well’ to provide a continuous record for assignment of daily clinical status. Specifically, the study's Serious Adverse Event log (e.g. psychiatric hospitalisations) and scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Reference McElroy, Altshuler and SuppesMontgomery & Åsberg, 1979) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; Reference Weiss, Ostacher and OttoYoung et al, 1978) from quarterly independent evaluations by trained raters (Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrichSachs et al, 2003) provided additional information for confirmation of the CMF status. For example, when there was a discrepancy between the CMF score and other assessments, the ‘worst’ score was used (i.e. MADRS or YMRS scores indicative of a mood episode, or a psychiatric hospitalisation, were scored as the loss of ‘recovering’ status). Because patients in a longitudinal naturalistic study are assessed at variable intervals, the following procedures were used to assign days in recovering or recovered status over study intervals, as well as the number of days to changes in status (e.g. recovery or relapse) for survival analyses. When two identical status ratings were present at the beginning and end of any interval of time, each day of that interval was assigned the same clinical status rating. When clinical status differed at the start and end of a time interval, the midpoint of that interval was defined as the day of change to the new clinical status. For participants completing the full year of prospective study, the mean number of clinical CMF assessments was 9.34 (s.d.=7.31). The mean for the entire sample was 7.28 (s.d.=6.06) assessments.

Statistical analyses

The influence of anxiety comorbidity on the course of bipolar disorder was examined with statistical models that took into account bipolar subtype (I v. II) and the presence of recovering or recovered status at study entry. We examined three related outcome variables describing the course of bipolar disorder over time:

-

(a) days well, defined as the number of days during the year of longitudinal study that patients were assigned a recovering or recovered clinical status;

-

(b) days to recovering or recovered clinical status among patients who were depressed at study entry;

-

(c) days to relapse to a mood episode (defined as meeting CMF criteria for episode of depression, hypomania or mania) for patients who were recovered or recovering at study entry.

For the examination of days well, the presence of anxiety comorbidity was examined as a main effect, and bipolar subtype (I v. II) and recovering or recovered status at study entry were treated as covariates in mixed-model regression analyses. For assessment of days to recovery or relapse, bipolar subtype was treated as a covariate, and main effects of anxiety comorbidity were examined using Cox regression survival models.

Because the Q-LES-Q and the LIFE-RIFT were administered on a quarterly basis during the year of the study, we used a mixed-model regression analysis that examined all four prospective quarterly assessments (3, 6, 9 and 12 months) as outcome in a model that adjusted for within-subject correlations of measurement. In the respective models of prospective Q-LES-Q and LIFE-RIFT, baseline Q-LES-Q or LIFE-RIFT score was entered as a covariate, along with bipolar subtype and recovering or recovered status. Anxiety comorbidity was examined in the context of this model.

The presence of a current anxiety disorder was first examined using the variable ‘any anxiety disorder’, defined as having met DSM-IV criteria at study entry for currently having one of the following: panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or generalised anxiety disorder. Subsequently, these six disorders were examined individually for their significance in predicting longitudinal bipolar status.

RESULTS

Characteristics of participants

Diagnostic comorbidity data were missing for 8.3% of the sample. For the remainder of the sample, 293 (31.9%) met current criteria for any anxiety disorder, 122 (13.3%) met criteria for social anxiety disorder, 122 (13.3%) met criteria for generalised anxiety disorder, 78 (8.5%) met criteria for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, 62 (6.8%) met criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 44 (4.8%) met criteria for PTSD and 38 (4.1%) met criteria for agoraphobia without panic disorder.

At entry into the study 489 participants were categorised as recovering or recovered, 248 as depressed, 145 as hypomanic, manic or ‘mixed’ and 117 met criteria for one of the transitional categories between these states. One participant's clinical status at study entry was unknown. Owing to the heterogeneity and limited sample size for detailed analyses of anxiety comorbidity in the hypomanic/manic/mixed group, only the sample of those rated as depressed at study entry was included in the time to recovery analyses.

Loss to follow-up

In the year of the study, participants provided a mean of 300.7 days (s.d.=109.6) of follow-up data, with 67.9% of the sample providing a full year of data. Loss to follow-up was not significantly associated with recovering or recovered status at baseline, bipolar subtype (bipolar I v. II) or the presence of ‘any current anxiety disorders’. Of the individual anxiety disorders, only a PTSD diagnosis in interaction with baseline recovery status was linked to longitudinal study withdrawal; patients with PTSD who were not assigned recovering or recovered status tended to leave the study earlier, with a mean of 41.7 weeks (s.d.=16.4) of assessment for patients with current PTSD and 44.6 weeks (s.d.=15.3) for patients without PTSD. The examination of the proportion of days well during study participation (days well/days of observation) was used to complement analyses of the absolute number of days well; identical patterns of significance were obtained, except where noted.

Estimated days well and anxiety comorbidity

The mean number of estimated ‘days well’ for the sample as a whole was 199.2 days (s.d.=117.8). The predictive significance of any current anxiety disorder was examined in the context of a model that took into account the impact of baseline recovering/recovered status and bipolar subtype (I & II). These results are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Estimated impact of anxiety comorbidity on ‘days well’ over 12 months for patients with bipolar disorder

| Estimated loss of days well n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Core model | ||

| Not in recovery status (n=433) | 82.9 (25.1) | 0.0001 |

| Bipolar II subtype (n=251) | 13.3 (4.1) 1 | 0.1160 |

| Any anxiety disorder (n=251) | 39.3 (10.4) | 0.0001 |

| Number of anxiety disorders 2 | ||

| One v. none (n=140 v. 566) | 27.6 (8.1) | 0.0068 |

| Two v. none (n=83) | 43.5 (12.0) | 0.0007 |

| Three or more v. none (n=28) | 56.9 (11.5) | 0.0068 |

| Individual anxiety disorders 2 | ||

| Social anxiety disorder (n=102) | 34.2 (8.1) | 0.0028 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (n=107) | 29.0 (6.8) | 0.0105 |

| Panic with/without agoraphobia (n=62) | 29.7 (8.1) | 0.0385 |

| OCD (n=53) | 41.6 (11.0) | 0.0072 |

| PTSD (n=38) | 43.5 (11.7) | 0.0162 |

| Agoraphobia without panic (n=35) | 32.3 (7.1) | 0.0849 |

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

1. P <0.03 according to the proportion of days well

2. The number of anxiety disorders and the individual anxiety disorders were examined in a model including recovery status and bipolar subtype as covariates

A clinical status of recovering or recovered at study entry was associated with 83 additional days well (F=117.4, d.f.=1,816; P=0.0001). Bipolar subtype was not significantly associated with the number of days well (F=2.48, d.f.=1,816; P=0.1160), but a trend towards a worse course was significant when assessed as the proportion of days well: bipolar II subtype predicted 4.1% fewer days well by this measure.

Having at least one current anxiety disorder was associated with a loss of 39.3 days well (F=22.4, d.f.=1,816; P=0.0001). Moreover, having multiple anxiety disorders had an additive influence on the loss of days well, with a loss of 27.6 days for a single anxiety disorder, 43.5 days for two current anxiety disorders and 56.9 days for three or more current anxiety disorders. Of the individual anxiety disorders, all were significant predictors of fewer days well except for agoraphobia without panic disorder, which reflected only a trend towards a poorer course (P=0.085). A ‘days well’ loss of 29-30 days was found for panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder; and a loss of 34-44 days was found for social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and PTSD.

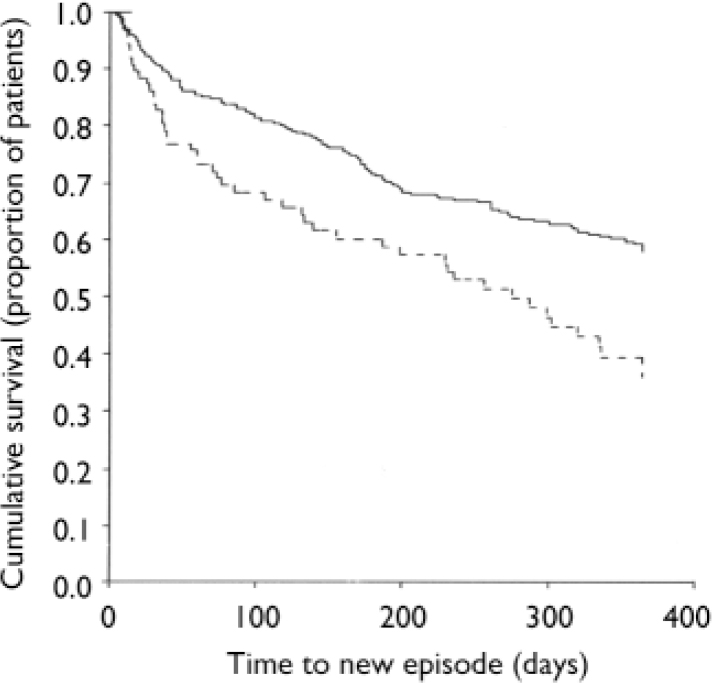

Risk of relapse

Of the participants who met criteria for recovering or recovered status at study entry, 165 (41.4%) relapsed during the year of prospective study. Bipolar subtype (I v. II) did not significantly predict risk of relapse. Any current anxiety disorder was associated with significantly greater risk of an earlier relapse, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.764 (χ2=10.9, P=0.001) (Fig. 1). There was evidence of increasing risk for number of anxiety disorders: HR=1.55 for one disorder and HR=2.17 for two or more disorders. Of the individual anxiety disorders, only social anxiety disorder (HR=2.07; χ2=11.6; P=0.0001) and PTSD (HR=2.45; χ2=6.1, P=0.013) were significantly associated with an elevated risk of relapse (Table 2).

Fig. 1 Survival curve for patients with bipolar disorder having recovering or recovered status at study entry with (dashed line) and without (solid line) a current anxiety disorder.

Table 2 Impact of anxiety comorbidity on time to a mood episode for patients with bipolar disorder assigned recovering/recovered status at study entry (n=399)

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Bipolar I subtype (n=297) | 0.767 (0.55–1.07) |

| Any anxiety disorder (n=87) | 1.76 (1.26–2.47) |

| Number of anxiety disorders 1 | |

| One v. none (n=52 v. 312) | 1.548 (1.02–2.35) |

| Two or more v. none (n=35) | 2.172 (1.36–3.46) |

| Individual anxiety disorders 1 | |

| Social anxiety disorder (n=43) | 2.072 (1.36–3.15) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (n=35) | 1.368 (0.83–2.26) |

| Panic with/without agoraphobia (n=20) | 1.57 (0.82–2.98) |

| OCD (n=15) | 0.841 (0.37–1.90) |

| PTSD (n=11) | 2.452 (1.20–4.99) |

| Agoraphobia without panic (n=10) | 1.361 (0.56–3.32) |

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

1. The number of anxiety disorders and the individual anxiety disorders were examined in a model including bipolar subtype as a covariate

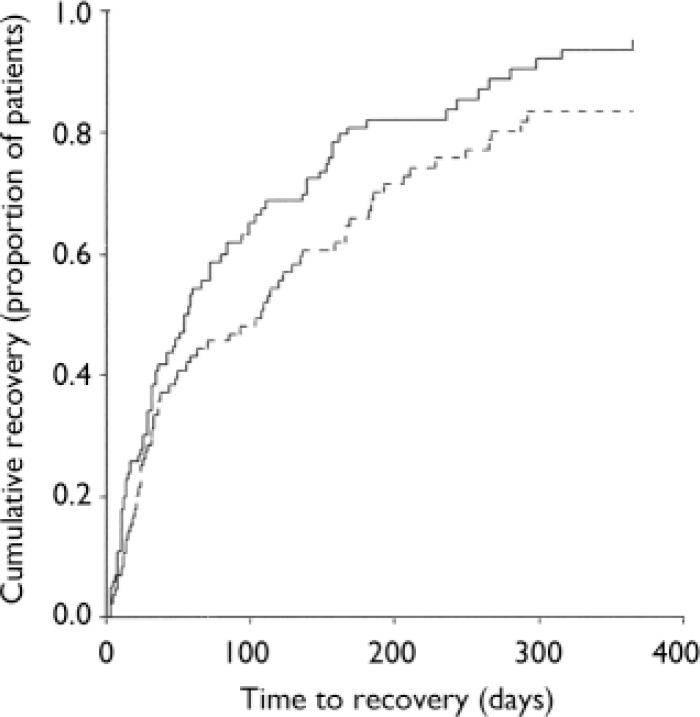

Recovery from depression

Of the patients who were depressed at study entry, 151 (80.7%) recovered during the 12-month observation period. The presence of any current anxiety disorder was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of a timely recovery (HR=0.661; χ2=5.41, P=0.020) (Fig. 2). Of the individual anxiety diagnoses, only social anxiety disorder was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of timely recovery (HR=0.452; χ2=11.17, P=0.0008). These results are summarised in Table 3.

Fig. 2 Cumulative recovery for patients with bipolar disorder, with (dashed line) and without (solid line) a current anxiety disorder, controlling for bipolar subtype at study entry.

Table 3 Impact of anxiety comorbidity on recovery for patients with bipolar disorder assessed as having depression at study entry (n=187)

| HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Bipolar subtype (n=129) | 1.107 (0.76–1.61) |

| Any anxiety disorder (n=86) | 0.661 (0.47–0.94) |

| Number of anxiety disorders 1 | |

| One v. none (n=54 v. 101) | 0.709 (0.49–1.03) |

| Two or more v. none (n=37) | 0.558 (0.35–0.89) |

| Individual anxiety disorders 1 | |

| Social anxiety disorder (n=34) | 0.452 (0.28–0.72) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (n=36) | 1.256 (0.84–1.88) |

| Panic with/without agoraphobia (n=21) | 0.668 (0.39–1.15) |

| OCD (n=16) | 0.889 (0.50–1.57) |

| PTSD (n=9) | 1.074 (0.52–2.21) |

| Agoraphobia without panic (n=7) | 0.971 (0.43–2.21) |

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

1. The number of anxiety disorders and the individual anxiety disorders were examined in a model including bipolar subtype as a covariate

Quality of life and role functioning

In addition to assessing the impact of anxiety disorders on the course of bipolar disorder, we also evaluated their impact on quality of life and role functioning. Scores on the Q-LES-Q at study entry ranged from 7 to 100, with a mean score of 54.25 (s.d.=19.58). After adjusting for scores at study initiation, quality of life as assessed by the Q-LES-Q was significantly lower (approximately 5.6 points) for patients with at least one current anxiety disorder (F=9.61, d.f.=1,438, P=0.0021). In addition, the presence of two anxiety disorders was associated with even lower scores (P=0.004). Of the individual anxiety disorders, social anxiety disorder (P=0.007) and PTSD (P=0.002) were each associated with lower quality-of-life scores.

Scores on the LIFE-RIFT at study entry ranged from 4 to 20, with a mean score of 11.70 (s.d.=3.87). Poorer role functioning over the course of the study was also linked to the presence of anxiety comorbidity. Relative to levels at study initiation, LIFE-RIFT impairment scores were significantly higher (about 0.6 points) for patients with at least one current anxiety disorder (P<0.0001). The presence of two or more anxiety disorders was associated with even poorer functioning. As found for the Q-LES-Q, social anxiety disorder (P<0.0001) and PTSD (P<0.005) were individually linked to poorer functioning as assessed by the LIFE-RIFT.

Controlling for substance use

Previously we have shown that substance use and anxiety disorders co-occur in individuals with bipolar disorder (Reference Simon, Otto and WeissSimon et al, 2004b ; Reference Henry, Van den Bulke and BellivierKolodziej et al, 2005) and substance use disorders are associated with a worse course (Reference Sung, Erklanli and AngoldWeiss et al, 2005). To clarify the independent association between anxiety disorders and course of bipolar disorder, we included alcohol and other substance use disorders as covariates in the above analyses. All significant effects for anxiety disorders were retained, with the single exception of the reduction of the significance of PTSD as a predictor of relapse to a marginal level (P<0.058).

DISCUSSION

Cross-sectional and retrospective studies of patients with bipolar disorder suggest that anxiety disorder comorbidity is prevalent and is an independent marker of greater severity of bipolar illness. In this large-scale prospective examination of the course of bipolar disorder, we found that current anxiety disorders were associated with worse course of bipolar disorder across a year of prospective study. Anxiety disorder comorbidity was associated with the estimated loss of 39 days well relative to patients without anxiety comorbidity. This effect was intensified for patients with more than one anxiety disorder. Patients who were depressed at study entry took longer to recover if anxiety disorder was present. Likewise, patients with anxiety disorders assessed during a period of recovery relapsed into a new mood episode more quickly. Finally, current anxiety comorbidity was associated with poorer quality of life and role functioning over the course of the year.

The consistency of our results across bipolar subtypes (I v. II) and phases of the disorder (recovering or depressed) is of particular importance for the understanding of the nature of the association between anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder. Our results indicate that the predictive significance of anxiety comorbidity is not simply due to a misattribution of the anxiety, panic, agitation or rumination that can co-occur with depressive, (hypo)manic or mixed states (see Reference Perugi, Akiskal and RamacciottiPerugi et al, 2001). In our study we documented a negative impact of anxiety disorders on bipolar course, even when anxiety was assessed during periods of relative euthymia. Because mood state and comorbidity are often confounded in cross-sectional data, our study documents the cost of anxiety comorbidity to bipolar course in a way that cross-sectional studies cannot.

Individual anxiety disorders

There was evidence that all of the individual anxiety disorders studied had an impact on outcome, except for agoraphobia without panic attacks. In estimates of the hazard for lower recovery and higher relapse as well as disruptions in quality of life and role functioning, PTSD and social anxiety disorder had prominent roles. Although social anxiety disorder has received relatively less attention in bipolar disorder (Reference Otto, Perlman and WernickePerugi et al, 1999), it has been associated with poorer outcome for unipolar depression. For example, in a 12-month prospective study, Gaynes et al (Reference Frank, Cyanowski and Rucci1999) found that the presence of anxiety disorder (primarily social phobia) enhanced the risk of persisting depression for patients who were depressed at study entry. Similar results have been reported for other anxiety disorders in patients with unipolar depression (Reference Coryell, Endicott and WinokurCoryell et al, 1992; Frank et al, 2000).

The potentially complex relationship between anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder is reflected in recent studies of comorbid PTSD. As reviewed by Otto et al (Reference Montgomery and Asberg2004), patients with bipolar disorder are characterised by high rates of risk factors for PTSD. Likewise, PTSD itself is associated with a number of factors associated with a worse course of bipolar disorder, including emotional lability, hyperarousal, sleep disruption, substance use, and avoidance, with the potential for increased social isolation. This potential for a reciprocal negative influence of anxiety comorbidity and bipolar disorder could serve to maintain the anxiety disorder and worsen the course of bipolar disorder. Substance use disorders may also arise as a consequence of the anxiety disorders (e.g. Reference Simon, Otto and WisniewskiSung et al, 2004), but as noted, in this study we showed that the predictive significance of anxiety comorbidity remained after controlling for the influence of comorbid substance use disorders.

Our study does not address whether anxiety disorders are themselves a product of a unique subtype of bipolar disorder distinct from type I or II status (e.g. Reference Leon, Solomon and MuellerMacKinnon et al, 2002; Reference Perugi, Akiskal and ToniRotondo et al, 2002). For example, a worse course of bipolar disorder in people with anxiety comorbidity may not be a result of the effects of the anxiety disorder directly (e.g. increased affective instability and increased role and social challenges because of anxiety and avoidance), but may reflect a unique biological subtype of bipolar disorder that is manifested by anxiety comorbidity, early age at onset and a poorer illness course. Our study supports the need for work targeting the treatment of anxiety comorbidity, to clarify the effects of this separate treatment on the course of the mood disorder. Both cognitive-behavioural and pharmacological strategies hold promise for this treatment goal (Reference Montgomery and AsbergOtto et al, 2004).

Our study did not examine the link between anxiety comorbidity and the type and intensity of pharmacotherapy received over the course of the year of prospective study. At study entry, the presence of anxiety disorders was not significantly associated with the adequacy of mood stabiliser use or the presence of antipsychotic or stimulant medications, but was linked to greater use of antidepressant and benzodiazepine medications (Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and SheehanSimon et al, 2004a ). None the less, we cannot rule out the possibility that the presence of anxiety disorders is associated with greater drug sensitivity, leading to differential treatment over the course of study.

Concluding remarks

In a large, prospective study we found evidence for a worse course of bipolar disorder among patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. Our data further demonstrated that anxiety disorders present during relative euthymia are implicated in higher rates of bipolar relapse, suggesting that the detrimental effects of anxiety do not simply represent a feature of current mood states. Most of the individual anxiety disorders were implicated in this relationship, with even greater mood disruption and disability associated with a greater number of comorbid anxiety conditions. Of the individual anxiety disorders, social anxiety disorder and PTSD had prominent roles. Treatment outcome studies targeting anxiety comorbidity have the potential to clarify further the nature of the relationship between anxiety comorbidity and course of bipolar disorder.

APPENDIX

Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP–BD) investigators and collaborators

STEP–BD contract

Gary S. Sachs, MD (principal investigator); Michael E. Thase, MD (co-principal investigator).

STEP–BD Clinical Coordinating Center

Gary S. Sachs, MD; Mark S. Bauer, MD (coinvestigator); Leslie Leahy,* PhD; Jane N. Kogan, PhD; Ellen B. Dennehy, PhD; Jennifer A. Conley, MA; Jaimie L. Gradus, BA; Stephen M. Gray,* BA; Jacqueline Flowers,* BA; Mandy Graves, BA.

STEP–BD Data Coordinating Center

Stephen Wisniewski, PhD.

STEP–BD site principal investigators and co-principal investigators

Lauren B. Marangell, MD, and James M. Martinez, MD, at Baylor College of Medicine; Joseph R. Calabrese, MD, and Melvin D. Shelton, MD, at Case Western Reserve University; Michael W. Otto,* PhD; Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD, and Gary S. Sachs, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School; R. Bruce Lydiard,* MD, at the Medical University of South Carolina; Joseph F. Goldberg, Footnote * MD, at New York Presbyterian Hospital and Weill Medical College of Cornell University; James C.-Y. Chou, MD; and Joshua Cohen, DO, at New York University School of Medicine; John Zajecka, Footnote * MD, at Rush–Presbyterian St Luke's Medical Center; Terence A. Ketter, MD, and Po W. Wang, MD, at Stanford University School of Medicine; Uriel Halbreich, Footnote * MD, at State University of New York at Buffalo; Alan Gelenberg, Footnote * MD, at University of Arizona; Mark Rapaport, Footnote * MD, at University of California, San Diego; Marshall Thomas, MD; Michael H. Allen, MD, and David J. Miklowitz, PhD, at University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD, at University of Louisville School of Medicine; Jayendra Patel, MD, at University of Massachusetts Medical Center; Kemal Sagduyu, MD, at University of Missouri–Kansas City, School of Medicine, Western Missouri Mental Health Center; Mark D. Fossey, MD, and William R. Yates, MD, at University of Oklahoma College of Medicine; Laszlo Gyulai, MD, and Claudia Baldassano, MD, at University of Pennsylvania Medical Center; Michael E. Thase, MD, and Edward S. Friedman, MD, at University of Pittsburgh Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; Peter Hauser, MD, at Portland VA Medical Center; and Charles L. Bowden, MD; and Cheryl L. Gonzales, MD, at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

STEP–BD Executive Committee

Mark S. Bauer, MD, Charles L. Bowden, MD, Joseph R. Calabrese, MD, Ellen B. Dennehy, PhD, Maurizio Fava, MD, Gary Gottleib, MD, Ellen Frank, PhD, Jennifer Harrington, MA, Terence A. Ketter, MD, Jane N. Kogan, PhD, David Kupfer, MD, Lauren B. Marangell, MD, David J. Miklowitz, PhD, Michael W. Otto, PhD, Jerrold F. Rosenbaum, MD, Matthew V. Rudorfer, MD, Gary S. Sachs, MD, Linda Street, PhD, Michael E. Thase, MD, Sean Ward and Stephen Wisniewski, PhD.

National Institute of Mental Health liaisons to STLP–BD

Matthew V. Rudorfer, MD; Joanne Severe, MS; Linda Street, PhD.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institutes of Health, under contract N01MH80001. Additional funding included DA00326 and DA15968 to R.D.W. and MH-01831-01 to N.M.S. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH. This article was approved by the publication committee of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP–BD). Core investigators and collaborators for STEP–BD are listed in the Appendix.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.