1.1 Introduction

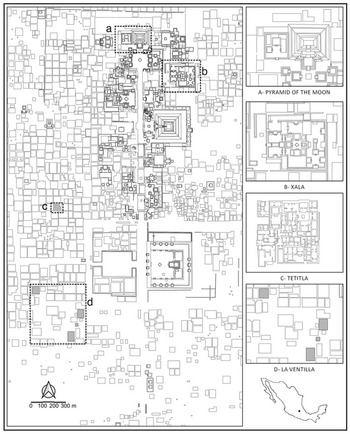

Teotihuacan was the largest city in ancient Mexico (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2017a; Fig. 1.1). Teotihuacan is also the archaeological site of pre-Hispanic Mexico and has been studied for the longest time: a century of formal archaeological research (Matos-Moctezuma, Reference Matos-Moctezuma2017). It has been proposed that the city was administered by a corporate government of four rulers who maintained order and control over five centuries (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2017a). Between 100 and 200 CE, many structures were built, such as the pyramids of the Sun and the Moon and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. The control that Teotihuacan had over the area’s obsidian mines led not only to its exploitation, but also to the presence of multiple workshops where this volcanic glass was converted into instruments and objects that were distributed throughout Mesoamerica (Carballo, Reference Carballo2011). The productive system of the Teotihuacan valley turned it into a city that quickly extended its power and influence in four directions (Cowgill, Reference Cowgill1997). We know that in the interior of the city there were neighborhoods and sectors where groups of different ethnic origins coexisted with the purpose of maintaining relationships and communication between the central government and its regions of origin (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2015, see also Meza-Peñaloza, Reference Meza-Peñaloza2015). This development reached its highest level during the Xolalpan period (350–550 CE), when the city also reached its largest extension and population size, around 150,000 inhabitants, and likely one of the major cities in the world at that time (Valadez, Reference Valadez1992). Despite the great development, within this urban area there were strong social tensions which led to moments of violence at the city’s fall. Although control was recovered, its power was reduced to the degree that the central government practically disappeared and the control of resources ended in the hands of other peoples (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla and Robb2017b).

Archaeoprimatology is an interdisciplinary research area that links primatology and archaeology (Urbani, Reference Urbani2013). Archaeoprimatological studies explore the interface between humans and nonhuman primates in the past, where the liminality of this relationship is examined over a long chronological period (Urbani, Reference Urbani2013). In doing so, archaeoprimatological research scrutinizes primate remains from archaeological sites and the material culture that depicts primates. This chapter examines the representation and actual presence of nonhuman primates in one of the largest pre-Hispanic cities of Mesoamerica. Therefore, the goals of the present research are to review existing information on primates in the Teotihuacan culture. To achieve this, it is proposed (a) to describe biological remains of primates found in Teotihuacan, (b) to present information on Teotihuacan material culture where monkeys are represented, (c) to evaluate the contexts of the archaeological material in order to infer the possible roles of nonhuman primates in the Teotihuacan society, and (d) to review the extent of the interface between the Teotihuacan society and its primates with other non-Teotihuacan Mesoamerican archaeological regions.

1.2 The Presence of Monkeys in Teotihuacan

1.2.1 Osteological Remains

Focusing on Teotihuacan, there have been several occasions when, either by personal communication or by comments in various publications (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014; Valadez and Childs-Rattray, 1993), the discovery of osteological remains of monkeys in various sectors of the city has been reported. An example of purported reports of primate remains refers to a monkey femur at the site of Oztoyahualco in the Teotihuacan periphery (García del Cueto, Reference García del Cueto, Estrada, López- and Wilchis1989), but without indicating the exact location or its temporality (as reviewed by Valadez and Ortiz, Reference Valadez, Ortiz and Manzanilla1993). Thus, these mentions have been discarded, and currently only three examples of primate biological material are fully known in Teotihuacan contexts.

It was almost a century ago when Gamio (Reference Gamio1922) presented commentaries on Teotihuacan animal skeletal remains. Subsequently, in the 1970s, Starbuck (Reference Starbuck, McClung de Tapia and Childs-Rattray1987) reported no primates in the first large-scale zooarchaeological survey in Teotihuacan. As well as the sites of Xalla (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2002) and the Pyramid of the Moon (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014; N. Sugiyama et al., Reference Sugiyama2014, Reference Sugiyama, Valadez and Rodríguez2017) that have ample zooarchaeological research and evidence of primate remains, other zooarchaeological studies have been carried out at specific Teotihuacan localities such as Teopancazco (Manzanilla and Valadez, Reference Manzanilla and Valadez2017; Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2006, Reference Rodríguez2010, Reference Rodríguez, Manzanilla and Valadez2017; Valadez et al., Reference Valadez, Rodríguez, Christian, Silva, Manzanilla and Valadez2017), Quetzacoalt pyramid (Valadez et al., Reference Valadez, Rodríguez, Cabrera, Cowgill and Sugiyama2002), and Oztoyahualco (Valadez, Reference Valadez and Manzanilla1993) and no primates have been found. For example, in the Teotihuacan site of Oztoyahualco, a total of 45 different animals have been found, mostly mammals, mainly dogs and leporids (Valadez, Reference Valadez and Manzanilla1993). The vast majority of the sample is from the Xolalpan phase (450–650 CE), when most of the representation of primates were made (see Table 1.2), but no primate was found at this site. This site was a residential area located in the northwestern area of the Teotihuacan valley (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla and Manzanilla1993). Also, a preliminary assessment of the archaeofauna at the Teotihuacan site of La Ventilla (excavation seasons 1992–1994, sectors 1–3) was conducted by D. Ruiz-Ramoni and B. Urbani (2018, pers. obs.). Remains of dogs and coyote (Canis familiaris and C. latrans), felids (cf. Leopardus), rabbits (Lagomorpha), sheep (Caprinae), and vultures (Cathartidae), were frequently observed at this site. However, there were no primate remains. Information will now be presented with the only three confirmed specimens of primates registered in Teotihuacan.

1.2.1.1 Primate of the Moon Pyramid

Family Atelidae Gray, 1825

Subfamily Atelinae Gray, 1825

Genus Ateles Geoffroy, 1806

Referred material: a left proximal ulna and a left distal humerus of a single individual (MNI=1, incomplete) (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014; N. Sugiyama et al., Reference Sugiyama, Somerville and Schoeninger2015).

Description and comparison: because of “the small size of the elements in question suggested that we are dealing with an immature individual” (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014: 115); thus, “likely [the remains are] from a young individual considering its relatively small size” (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014: 206). No further descriptive and comparative information was provided.

Context: the Pyramid of the Moon was an uninterrupted construction of several structures, seven buildings built throughout the history of Teotihuacan (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014). Throughout this process, various ceremonial events took place that included the sacrifice of humans and animals under very different schemes. After the completion of Phase 5 and before the creation of Phase 6 of the Pyramid of the Moon, Entierro 5 (Burial 5) was made, in which the bones of a Geoffroy’s spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) were found (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014). These primates and other animal remains were isolated objects in ceremonial secondary deposits. In these cases, it is considered that the fundamental symbolic value of these pieces is related to the particularity of the objects themselves. The two primate remains were found in very poor condition. Unfortunately, no other feature was obtained that would help interpret the original placement and use of the deposited material.

Burial 5 (6 × 4 × 3.5 m) was discovered in 2001 and dated approximately at 350–400 CE, likely during the late Tlamimilolpa period (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro2012; Sugiyama and López-Luján, Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a, Reference Sugiyama, López-Luján, López-Luján, Carrasco and Cuéb). Looking toward the West, three adult individuals (>40 years of age) were found seated in “lotus flower” positions as in Mayan elite burials (Sugiyama and López-Luján, Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a); this is a rare arrangement of the Classic Mesoamerican chronology, and similar to those of the Mayan area of Kaminljuyú and Uaxactum (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro2012; Sugiyama and López-Lujan, Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a). The hands were crossed in front of the individuals and two of them were superimposed on skulls of animals. Complete animals were placed in front of each of the three individuals and scattered remains of rattlesnakes and other animals like the monkey, were found throughout the space, close to wolves, eagles, and cougars (probably related to the military orders), that were chosen by the Teotihuacan government as basic actors in their ceremonies and the main species as victims of appropriate sacrifices (Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014; Sugiyama and Cabrera-Castro, Reference Sugiyama and Cabrera-Castro2004). These burials are associated with shell earflaps decorated with jadeite and pectorals of green stone similar to those of the Mayan area. The jadeite of this burial comes from the Motagua valley in Guatemala. This kind of material culture is found in Mayan elite burials (Sugiyama and López-Luján, Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a). A pectoral was found with an X-shaped design that is typical of representations associated with the Mayan elite (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro2012). In addition there are other objects made of green stone that represent humans in similar position to the buried individuals., There are obsidian statues and snails as well as obsidian objects representing serpents and knives that were associated with the three bodies (Sugiyama and López-Luján, Reference Sugiyama, López-Luján, López-Luján, Carrasco and Cué2006b). These objects seem to follow an ordered pattern (Sugiyama and Cabrera-Castro, Reference Sugiyama and Cabrera-Castro2004). There are also remains of grasses in this burial. Perhaps one of the buried characters was from the highest Teotihuacan elite, and accompanied by other two Mayan elite subjects (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro2012; Sugiyama and López-Luján, Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a). There is no other funeral niche like Burial 5 in Teotihuacan in terms of configuration and its Mayan association (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro2012; see also Manzanilla and Serrano, Reference Manzanilla and Serrano1999).

Remarks: “two [monkey] bones, along with some unidentified irregular and flat bone, were deposited just to the east of the sacrificed wolf. This was an extraordinary discovery which represents the second instance of this species ever reported at Teotihuacan… Unfortunately, this secondary burial of the forelimb did not provide any surface features to interpret how they were utilized or what the final product would have look like… Most likely, this forearm was brought into Teotihuacan and deposited bare” (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014: 206). “Whether these elements reached the city center as skeletal parts or as live individuals is uncertain, but it certainly suggests fauna products moved across long distances” (N. Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2014: 115).

Material: The specimen from the Pyramid of the Moon is deposited at the Pyramid of the Moon Project facility in San Juan Teotihuacan, Mexico (S. Sugiyama, 2018: pers. comm.). No further observations and morphometric comparisons were made with postcranial material of current Mesoamerican primates in order to fully determine the genus (Ateles, Alouatta, or eventually Cebus).

1.2.1.2 Primate of Xalla

Family Atelidae Gray, 1825

Subfamily Atelinae Gray, 1825

Genus Ateles Geoffroy, 1806

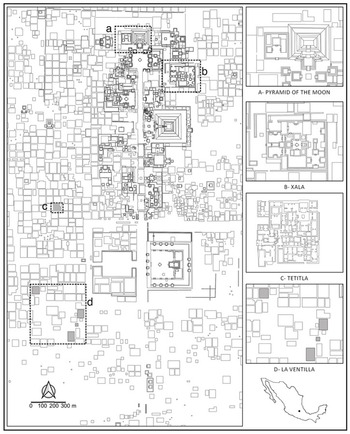

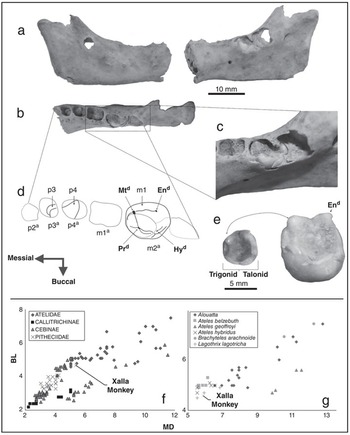

Referred material: LP-IIA-UNAM 43271; a fragmented hemimandible with the incomplete coronoid process, and the horizontal branch lacking the distal end at the level of p2 (symphysis absent) (Fig. 1.2a, b); lower premolars (p3–p4) and first lower molar (m1) are present but not erupted (Fig. 1.2c, d). A second lower molar (m2) without the root developed is associated with this hemimandible (Fig. 1.2e).

Figure 1.2 Xalla monkey (43271). (a) lingual (left) and buccal (right) view; (b) oclusal view; (c) detail (in buccal view) of uneruptedm1; note that this tooth is displaced posteriorly and located under the m2 alveolus; (d) diagram of the occlusal view; the m1 dental topology is highlighted; (e) m2 in occlusal view (left) and semi-lateral (right); (f) scatter plot showing the position of the Xalla monkey in relation to buccolingual (BL) and mesiodistal (MD) m1 values (in mm) with comparative sample of platyrrhines; (g) scatter plot showing the position of the Xalla monkey in relation to BL and MD m1 values of members of the family Atelidae. Abbreviations: p, premolar; m, molar; Prd, protoconid; Mtd, metaconid; End, entoconid; Hyd, hypoconid. (Photographs by D. R.-R.).

Table 1.1. Xalla monkey (LP-IIA-UNAM 43271) dental measurements

| p2 | p3 | p4 | m1 | m2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | L | W | L | W | L | W | L | W |

| 2.59a | 2.39a | 2.82a | 3.00a | 2.53a | 4.29a | 3.15a | 4.79 | 5.15 |

| 5.34* | 4.59* | |||||||

Measurements: mesiodistal [MD] and buccolingual [BL] dimensions of premolars and molars in mm. Abbreviations: p, premolar; m, molar; L, length; W, width; a, alveolus; *; measures taken at m1 without erupting.

Description and comparison: LP-IIA-UNAM 43271 is a platyrrhine because it has three lower premolars, p3 (Fig. 1.2a, b, d) (Table 1.1). It corresponds to an infant individual because molars are not fully erupted (Fig. 1.2c, d). In p3 and p4, only one main cusp, as well as an accessory one in p3 is present. Molars cuspids are sharp unlike those in Cebids. Also, molars are quadrangular (Fig. 1.2d, e), as in most of the platyrrhines except Alouatta, characterized by a more rectangular shape with a narrow area between the trigonid and talonid. The m1size coincides with that of the family Atelidae (Fig. 1.2f). Within this family, it is one of the smallest, certainly excluding the larger Ateles, Alouatta, and Brachyteles (Fig. 1.2g); however, the size of this m1 is close to Ateles hybridus and Lagothrix lagotricha, used as non-Mesoamerican control primates. 43271 has a notch in front of the protoconid and metaconid that it is well-differentiated for the genus Ateles. This dental morphology is also repeated for m2 (Fig. 1.2e). The m2 has the entoconid and hypoconid more separated (bucco-lingually) than the other observed Ateles. As expected for an infant, the mandibular angle is underdeveloped, and correspond to that of an Ateles (Fig. 1.2a).

Context: Xalla is a government palace of Teotihuacan (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2017a, Reference Manzanilla and Robbb) and dates from with the Late Classic period (300–700 CE). The hemimandible appeared in a pit (activity area 43), as part of the workshops of the so-called Plaza 5 (Pérez, Reference Pérez2005; Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2002), which was intentionally dug in the tepetate (yellowish stone used in construction for floors) of the plaza in the southern sector of Xalla. It mainly contained wasted ceramics, polished lithics, and projectile tips, as well as slate and mica, some of them wasted as ritual and offerings materials. Various ceramics were identified, from cajetes (clay bowls) to a seal, a zoomorphic figurine, a flute, obsidian, projectile tips, remains of various tools, a polished lithic, a mortar, a metate hand stone, green stone, a fragment of metal in its natural state, mica, a worked slate, and two seashells. In addition there is an association with other zooarchaeological material such as a needle made of deer bone (Odocoileus virginianus) and a smooth bone plate from a turtle (Trachemys scripta), as well as human bone chisels, an omichicahuaztli (musical instrument made on human long bone with slits for the purpose of generating sound when brushed with a rod), and a fragment of a human bone engraved with several lines. For example, in the Teopancazco neighborhood of Teotihuacan, the inhabitants had a tradition of placing waste materials or materials still in use, in places such as pits or fills, where they remained as a testimony of their activities in specific spaces of the neighborhood (Manzanilla et al., Reference Manzanilla, Rodríguez, Pérez and Valadez2011; Manzanilla and Valadez, Reference Manzanilla and Valadez2017).

Remarks: The material corresponds to an infant monkey, as evidenced by the low development of the mandibular angle. Although this material corresponds to an infant of a small Ateles, there are not enough diagnostic characters in this specimen to fully identify it at the species level. The only Ateles in the region of Mexico is A. geoffroyi, but the size of m1 differs with respect to this species: it appears to be an exception in this single specimen. It is important to note that the material shows porosity around the alveolus (Fig. 1.2b, c), which is also observed in sick and captive mammals (D. Ruiz-Ramoni, pers. obs.).

Material and methods: The specimen from Xalla (43271) described here is deposited at the Laboratory of Paleozoology of the Anthropological Research Institute at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (LP-IIA-UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico. Observations and morphometric comparisons were made with material from living Platyrrhini collections deposited at the Museo de la Estación Biológica Rancho Grande (MEBRG) in Maracay, Venezuela, and the Museo de Historia Natural La Salle (MHNLS) in Caracas, Venezuela. Measurements were taken using a digital caliper (± 0.1 mm, max. 150 mm; Mitutoyo™).

1.2.1.3 Primate of the Plaza of the Columns

Recent news releases reported the presence of a spider monkey recovered in an offering (Ofrenda D4) of the Plaza of the Columns (Anonymous 2018, 2019; Paz-Avendaño, Reference Paz-Avendaño2019; Salinas-Cesáreo, Reference Salinas-Cesáreo2018). This monkey remain is “particularly interesting because his hands are tied behind its back” (Paz-Avendaño, Reference Paz-Avendaño2019) and “it is the first time that the complete body of a monkey has been found [in Teotihuacan] that was surely brought from abroad, from the Gulf, the Pacific Ocean or the Mayan zone” as indicated by S. Sugiyama (Salinas-Cesáreo, Reference Salinas-Cesáreo2018). It is associated with other faunal remains such as rattlesnakes, a cougar cranium, and a golden eagle as well as shells (Anonymous 2018, 2019; Paz-Avendaño, Reference Paz-Avendaño2019). The associated material culture included green stones and obsidian artifacts (Anonymous, 2018). In addition, in another part of the plaza, there are multiple bone remains of adult human individuals; among them are three crania resembling those with modifications that are typical of the Mayan area (Anonymous, 2019). At this location, the chronological record of the possible interactions between people of Teotihuacan and the Mayan region ranged between 300 CE and 450 CE (Anonymous, 2019).

1.2.2 Material Culture

Within the Teotihuacan iconographic universe, mural painting has received most attention from researchers (e.g. de la Fuente, Reference de la Fuente1996a; Langley, Reference Langley1986; Miller, Reference Miller1973). In contrast, however, it has undoubtedly been the small figures of animals made from clay that have not yet been examined in detail within the Teotihuacan realm (but see, e.g. Gamio, Reference Gamio1922; Séjourné, Reference Séjourné1959). The reasons for the lack of further characterization of Teotihuacan zoomorphic representations are mainly its small size, fragmented conditions, being normally found in landfills and therefore difficult to contextualize. In this section, existing information on primate representations in the material culture of the Teotihuacan valley and its zones of influence is presented (Tables 1.1 and 1.3).

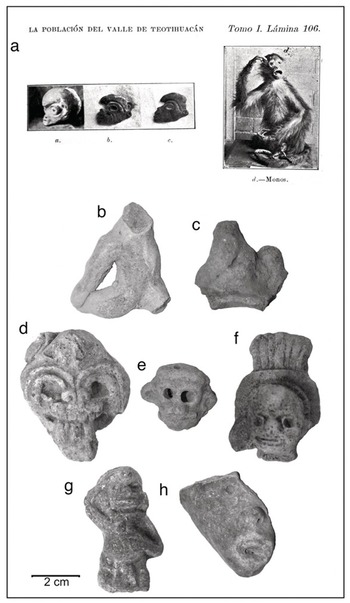

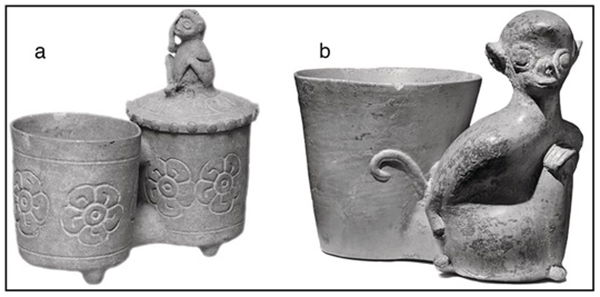

1.2.2.1 Pottery

During the pre-Classic (1500–300 BCE), at the site of Tlapacoya-Zoapilco of the Tlatilco culture, in the valley of Mexico, López-Austin (1996 in Nájera-Coronado, [Reference Nájera-Coronado2015]) reported a primate-like head that seems to be associated with the representation of the wind. The Tlapacoya, among others, were ancestors of the Teotihuacans (Vargas, Reference Vargas1978). Later, chronologically, the first historical archaeoprimatological reference to Teotihuacan – and possibly to Mexico – was provided by a pioneer of Mexican archaeology, Manuel Gamio (1883–1960). In a monumental work, Gamio (Reference Gamio1922) compared three primatomorphic clay pieces with the photograph of a spider monkey from the former Museum of Natural History in charge of the Directorate of Biological Studies of the early twentieth century (Fig. 1.3a). In these images, the frontal crests, rounded eyes, facial prognathism, and monkey “masks” can be seen. Later, excavations carried out by the Italian-Mexican archaeologist Laurette Séjourné (1911–2003) in the 1950s, mostly in the so-called Tetitla Palace, obtained numerous artifacts; some coming from burials and offerings and others from the fills (Séjourné, Reference Séjourné1966a–Reference Séjournéc). It highlights a collection of zoomorphic figures in small format (~5 cm), many of them made from molds. The collection consists of 114 pieces, 7 of which can be identified as representations of monkeys (Valadez, Reference Valadez1992). The criteria used for their recognition as images of monkeys are the body position with visible caudal bases (Fig. 1.3b, c), the bulging on the forehead (Fig. 1.3d, f, g), and the prognathous face (Fig. 1.3e, g, h). Figure 1.3h has an expression similar to a monkey vocalizing. In the images of complete monkeys from Tetitla, the base of the tail of the monkey can be seen (Fig. 1.3b, c). Similar to these monkey figurines, there are also others with no tails from the same site and time, which clearly represent humans (see Childs-Rattray, Reference Childs-Rattray2001: 541, figs. 133a, a). Figure 1.3h of the L. Séjourné collection resembles the one reported by Childs-Rattray (Reference Childs-Rattray2001: 550, fig. 146i, j; Fig. 1.4a in this chapter) at the base of a vessel and apparently was made with a production mold. Photographs of Séjourné’s ceramic collection with primatological features of the Tetitla architectural complex are fully published here for the first time (Fig. 1.3b–h) (Table 1.2).

Figure 1.3 Primate representations from the historical collections of Manuel Gamio (a), and Laurette Séjourné (b–h). (Gamio, Reference Gamio1922 [public domain] and pieces from L. Séjourné collection deposited at the Paleozoology Laboratory, Institute for Anthropological Research, UNAM. Photographs by B. U.).

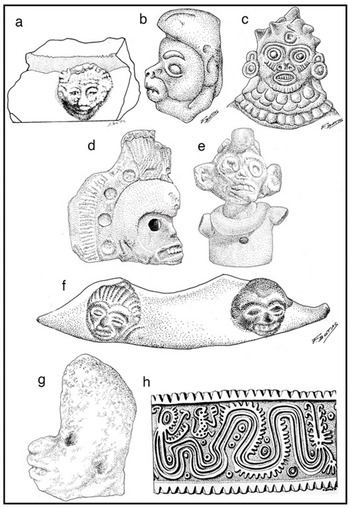

Figure 1.4 Primates from different locations of Teotihuacan.

Table 1.2. Primate representations in clay and stone from the Teotihuacan valley

| Objects | Location | Date | Repository | Figure | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primate adornos | Teotihuacan valley | – | – | 1.3a | Gamio (Reference Gamio1922: Plate 106) |

| Primate figurines | Tetitla | Classic undetermined, possibly Tlamimilolpa or Xolalpan (200–550 CE). | Laboratorio de Paleozoología, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.3b–c | L. Séjourné collection (R. Valadez-Azúa and B. Urbani pers. obs.) |

| Primate adornos | Tetitla | Classic undetermined., possibly Tlamimilolpa or Xolalpan (200–550 CE). | Laboratorio de Paleozoología, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.3d–h | L. Séjourné collection (R. Valadez-Azúa and B. Urbani, pers. obs.)a |

| Primate head adorno | Tlajinga | Late Xolalpan (~500–550 CE) | – | 1.4a | Childs-Rattray (Reference Childs-Rattray2001: 550, fig. 146i)b |

| Primate adorno | Teotihuacan valley | – | – | 1.4b | Séjourné (Reference Séjourné1966c: fig. 179) |

| Primate head in figurine | Zacuala | – | – | 1.4c | Sénourjé (Reference Séjourné1959: 105, fig. 82A) |

| Monkey head from pottery | Teotihuacan valley | 100 BCE–700 CE | Museo Diego Rivera Anahuacalli. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.4d | Hall 9, Diego Rivera Anahuacalli Museum |

| Monkey figurine | Teotihuacan valley | 100 BCE–700 CE | Museo Diego Rivera Anahuacalli. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.4e | Hall 9, Diego Rivera Anahuacalli Museum |

| Two monkey in pottery sherd | Teotihuacan valley | – | Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.4f | Main Studio, Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo House-Studio Museum |

| Monkey head from pottery | Neighborhood of the Merchants | Late Xolalpan (500–550 CE) | – | 1.4g | Valadez (Reference Valadez1992); Valadez and Childs-Rattray (Reference Valadez, Childs-Rattray, In, Rodriguez-Luna, Lopez-Wilchis and Coates-Estrada1993: 225, Photograph 2) |

| Cylindrical pintadera | Neighborhood of the Merchants | Early Xolalpan (350–400 CE) | – | 1.4h | Valadez (Reference Valadez1992); Valadez and Childs-Rattray (Reference Valadez, Childs-Rattray, In, Rodriguez-Luna, Lopez-Wilchis and Coates-Estrada1993: 226–227, Photographs 3 and 4) |

| Monkey head from pottery | Teotihuacan valley | Museo de Sitio Teotihuacán. Teotihuacan, Mexico | 1.5a | Social and Economic Organization Hall, Teotihuacán Site Museum | |

| Monkey head from pottery | Teotihuacan valley | Museo de Sitio Teotihuacán. Teotihuacan, Mexico | 1.5b | Aesthetic Manifestation Hall, Teotihuacán Site Museum | |

| Monkey head from pottery | Cosotlan | – | 1.5c | Sullivan (Reference Sullivan2007: 21, fig. 14E)c | |

| Monkey body with loincloth | Teotihuacan valley | National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside (44.3.27). Liverpool, UK | 1.5c | Scott (Reference Scott2005: 25, Plate 94)d | |

| Whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | La Ventilla, Structure 1, Burial 2 (season 1963) | Classic-Xolalpan (~350–550 CE) | Museo Nacional de Antropología (Inv. #10-80673). Mexico city, Mexico | 1.5e | INAH (2017); Solís (Reference Solís2009: 348, fig. 167a), |

| Whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | Teotihuacan valley | Classic undetermined, possibly Xolalpan (~350–550 CE) | Museo Nacional de Antropología. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.5f | Teotihuacan Hall, National Anthropological Museum |

| Globular monkey figurine | Teotihuacan valley | Classic (200–900 CE) | Museo de Sitio Teotihuacán. Teotihuacan, Mexico | 1.5g | Religion Hall, Teotihuacán Site Museum |

| Monkey head | Teotihuacan valley | Museo de Sitio Teotihuacán. Teotihuacan, Mexico | 1.5h | Flora and Fauna Hall, Teotihuacán Site Museum, Manzanilla (2016)e | |

| Monkey on double-chambered vase | Teotihuacan valley | 300–500 CE | Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA (AC1992.134.10) | 1.7a | Peterson (Reference Peterson1994) |

a A similar object to the one represented in Fig. 1.3d is deposited at the British Museum (Am2002,11.5). It is indicated with the “Production place: Teotihuacan,” and reported to be found in the cathedral of Mexico City. Another one is located at the American Museum of Natural History (30/3347) as part of the objects collected during the expedition of the Norwegian archaeologist Carl Lumholtz (1851–1922).

b There is also a modeled monkey-like piece in a Teotihuacan pottery base border from the period Late Xolalpan (~500–550 CE) (Childs-Rattray, Reference Childs-Rattray2001: 550, fig. 146j).

c A similar object was found in the Great Pyramid of Cholula (Tlachihualtepetl) in Puebla. It is deposited in the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University (1886.1.1061).

d Two similar pieces (30.0/1837, 30.1/7979) are deposited in the anthropological collection of the American Museun of Natural History, one of them labeled as “Teotihuacan V?” and found at Santiago Ahuitzotla, Mexico City. The other was found at Atzcapotzalco, also in Mexico City.

e This object was made in stone. The other objects in this table are made of clay.

L. Séjourné also presents a broad illustrative review of primates represented in the material culture of Teotihuacan, predominantly Tetitla as explained in the previous paragraph. Séjourné (Reference Séjourné1966c) shows a large plate where there are multiple illustrations of alleged primates in Teotihuacan (e.g. Fig. 1.4b), including some that are difficult as to identify with certainty as monkeys. Séjourné (Reference Séjourné1966c) suggests that unlike the representation of birds and canids, those of primates also have complementary elements, such as necklaces and mouth plates. Séjourné (Reference Séjourné1959) also indicates that at the site of Zacuala, some primates have pectorals (e.g. Fig. 1.4c), as well as pronounced bellies, frontal masks, and earflaps, and the number of representation of primates is only lower than that of canids. The frontal masks look like that of Ehécatl (God of the Wind) and the earflaps are similar to the oyohualli, typical earflaps of the Post-classic period of the central valley of Mexico.

In addition, something that had remained elusive in the characterization of Teotihuacan zoomorphic clay material is the presence of primate representations in the collection of the Mexican artists Frida Kalho (1907–1954) and Diego Rivera (1886–1957). Kalho’s interest in primates is known, as she had a pet spider monkey (Cormier and Urbani, Reference Cormier, Urbani and Campbell2008). For example, in the museum designed by Rivera to house his collection of archaeological artifacts there is a primate with a monkey “mask” and a nose that has platyrrhine features (Fig. 1.4d). In this collection there is also a figurine (Fig. 1.4e) that has some similarity to that of Teotihuacan influence found in Puebla (see Fig. 1.6e). In another collection owned by these artists, a border of a clay vase appears to have two monkeys with faces with nasal-mouth configuration similar to platyrrhine primates, as well as forehead hairs (Fig. 1.4f).

A couple of objects with primatological depictions had been found in the Barrio de los Comerciantes (Neighborhood of the Merchants). They are apparently related to societies from the Gulf of Mexico, which suggests the traffic of these objects from that region or that they were produced by people from these regions in the valley of Teotihuacan (Valadez, Reference Valadez1992). A head that appears to represent a monkey has a frontal crest and facial prognathism that seems distinctive to atelines (Fig. 1.4g; Valadez, Reference Valadez1992; Valadez and Childs-Rattray, Reference Valadez, Childs-Rattray, In, Rodriguez-Luna, Lopez-Wilchis and Coates-Estrada1993) as in some pieces found in Tetitla. The second object is a cylindrical ceramic stamp (Fig. 1.4h), possibly for corporal or textile use, with the representation of a snake, with a tail resembling a bouquet, apparently a rattle and an appendage at its base, perhaps its hemipenis (D. Ruíz-Ramoni, 2018: obs. pers.). The monkey appears on one side of the head of the snake, in profile and is recognizable by its forelock, forelimbs, and long tail, hands bulging but representing large size with long fingers, body upright, and hind limbs forward. The materials referred to in this neighborhood were found in a fill, while the seal was discovered under the floor of a room, suggesting it been buried on purpose and seems to indicate that it had a differential treatment.

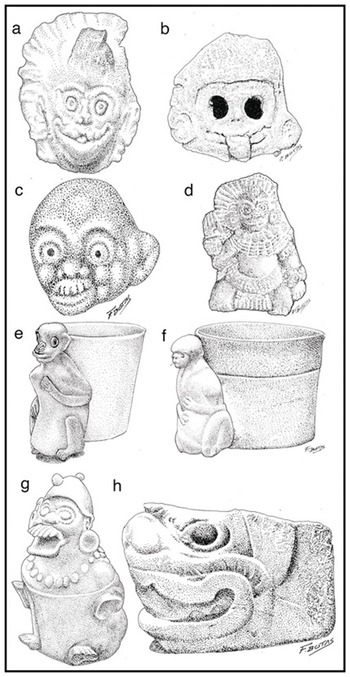

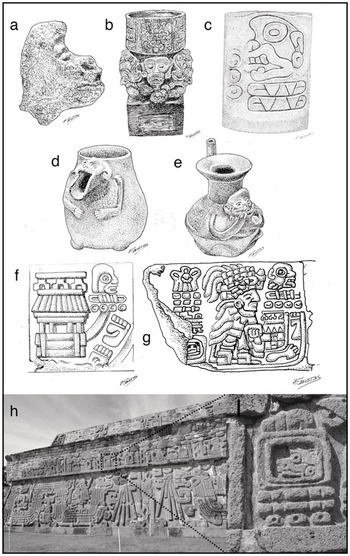

There is a piece in the Teotihuacan Site Museum, similar to one in the collection of L. Sejourné. This is an adornment with mask head and monkey pompadour as well as a narrow nasal configuration (Fig. 1.5a). The outline and eyes have diffuse reddish orange slip. In this collection there is another example of a monkey (Fig. 1.5b). It shows a primatomorphic mask, hair on the forehead, smiling face, with exposed tongue and earflaps, similar to those that are observed later in the Post-classic period of the central valley of Mexico, in Mexica representations of primates with oyohualli earflaps. Sullivan (Reference Sullivan2007) reports another monkey with the characteristic primate mask and pronounced front (Fig. 1.5c). Noguera (Reference Noguera1965) and Rivera-Dorado (Reference Rivera-Dorado1969) indicate that monkeys represented in Teotihuacan are clearly made with molds. An example of this type of production, including a monkey, is part of the historical collection excavated by the Swedish archaeologist Sigvald Linné (1899–1986) (Scott, Reference Scott2005). The monkey from this collection has a protuberance on the forehead, a primatomorphic mask, and prominent and rounded eyes as in other Teotihuacan representations of primates in addition to a pronounced belly, rounded eyes earflaps, and a loincloth (Fig. 1.5d).

Figure 1.5 Representation of primates from Teotihuacan, mainly in Mexican national collections.

There is a primatomorphic whistling vessel (14.2 × 11.9 × 17.7 cm) with a monkey with crossed arms, common in spider monkeys kept in captivity (B. Urbani, pers. obs.). It also has a tail, a prognathous face, a platyrrhine aligned nose, a protuberant belly, and bangs on the forehead (Fig. 1.5e). This object is deposited at the National Anthropological Museum. It was found in the Teotihuacan area of La Ventilla which is a complex that included a temple, institutional buildings, and an extended household area of highly specialized artisans who inhabited this complex between 300 CE and 650 CE (Gómez-Chávez, Reference Gómez-Chávez2000a, Reference Gómez-Chávezb; Serrano-Sánchez et al., Reference Serrano-Sánchez, Rivero de La Calle, Yépez-Vázquez and Serrano-Sánchez2003). Another similar vessel, also with the characteristic Teotihuacan orange slip, and deposited in the same museum, has similar characteristics, and in this case a more visible tail (Fig. 1.5f). A globular figurine in orange slip (12.3 × 19.5 × 11.3 cm), held at the Teotihuacan Site Museum, is a seated deity and depicts a monkey. This object also displays an element that seems to be observed in archaeological material of the Post-classic Aztec period: a protruding mouth that resembles the characterization of Ehécatl (Fig. 1.5g). Finally, it should be noted that in Teotihuacan, families in multi-ethnic complexes worshiped gods such as the god of the storm, as well as the monkey or the rabbit (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2016). The monkey, possibly “9 Monkey” as a deity, is represented in a rock sculpture (Fig. 1.5h).

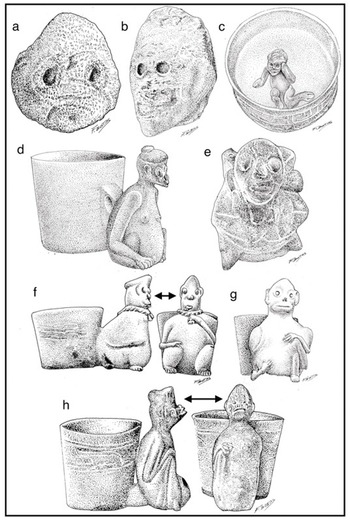

Outside the central valley of Mexico, there is ceramic material with representation of primates of clearly Teotihuacan characteristics (Table 1.3). A couple of primate-like adornos were found in Cerro de la Estrella, today’s south Mexico city (Fig. 1.6a, b). From the Mexican eastern region, specifically from the center of the state of Veracruz, there is a tripod vessel of Teotihuacan style (Fig. 1.6c; 12.2 cm × 11.7 cm), with a seated monkey inside looking at the horizon (Escobedo-Gonzalbo, Reference Escobedo-Gonzalbo2017); a vessel with a monkey in a similar posture was found in Teotihuacan (Fig. 1.7a). In the same region of the Gulf, Matos-Moctezuma (Reference Matos-Moctezuma2009) reports the presence of material of Teotihuacan influence in Cerro de los Monos (The Monkeys’ Mountain) located in the middle section of the Balsas River basin. A primatomorphic vase of San Martín Texmelucan, Puebla (16 × 20.8 × 13.8 cm, Fig. 1.6d) shows the Teotihuacan orange slip that seems to indicate mobility of this material from the metropolis to the south. This vessel was likely a ceremonial object (Solís, Reference Solís2009), and also represents a monkey with protuberant belly, prognathic face, and pronounced forehead. Another figure from the state of Puebla that used to belong to a private collection, now held at the Regional Museum of Cholula, shows some features that are reminiscent of the face of a primate, as a protuberance on the forehead, prognathic face, and a monkey “mask” (Fig. 1.6e). The region of Cholula had influence from Teotihuacan, as in the large pyramidal base of this Pueblan city (Marquina, Reference Marquina1972). Furthermore, in Teteles de Santo Nombre, a pre-Classic/Classic site in the state of Puebla, a polished green stone that resembles a primate head has been found (INAH, 2018); however, it might be a stylized human head. Cook de Leonard (Reference Cook de Leonard1957) reports two whistling vessels with primatological representations made from Teotihuacan orange slip and found in Ixcaquixtla, Puebla. In both vessels the monkeys have rounded eyes, pronounced foreheads, crossed arms on the chest, prognathic face, and nose with a line like a septum that separates the nostrils (Fig. 1.6f, g). One of them seems to have a rope around its neck that is held in the hand of the monkey (height: 16.5 cm; Fig. 1.6f), while the other has a prehensile tail visible on its right side (height 11.5 cm; Fig. 1.6g). On the other hand, there is another whistling vessel of doubtful provenance indicated as possibly from Mitla in the state of Oaxaca (Kidder et al., Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946). This object is located in the Field Museum of Natural History of Chicago (Fig. 1.6h) and is extremely similar to those of Teotihuacan and Puebla. It has a pronounced forearm and belly, a prognathic face, rounded eyes, and arms resting on its folded legs. Another example of an orange-slipped whistling vase with a similar monkey was found in Escuintla, Guatemala (Fig. 1.7b).

Table 1.3. Primatomorph pottery with Teotihuacan influence found south of the Teotihuacan valley

| Object | Location | Date | Repository | Figure | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monkey head from pottery | Cerro de la Estrella, Iztapalapa, Mexico valley. | – | Museo Fuego Nuevo. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.6a | Rafael Álvarez Pérez Hall, New Fire Museum |

| Monkey head from pottery | Cerro de la Estrella, Iztapalapa, Mexico valley. | – | Museo Fuego Nuevo. Mexico city, Mexico | 1.6b | Rafael Álvarez Pérez Hall, New Fire Museum |

| Tripod base with a “watching monkey” | Center of Veracruz, state of Veracruz | Early Classic (200–600 CE) | Museo del Amparo (Sala 6, Arte, forma y expresión), Puebla, Mexico | 1.6c | Escobedo-Gonzalbo (Reference Escobedo-Gonzalbo2017: n/p) |

| Whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | San Martín Texmelucan, state of Puebla (Tlaxcala) | Classic-Xolalpan (~350–550 CE) | Musée du quai Branly (ex-Pinart, former Boban, 71.1878.1033), Paris, France | 1.6d | Solís (Reference Solís2009: 348, fig. 167b) |

| Vase with alleged monkey | Cholula región, state of Puebla | – | Museo Regional de Cholula (Coll. Ángel Trauwitz and Museo José Luis Bello y González), Cholula, Mexico | 1.6e | Cultures of the Area of Teotihuacan Hall, Regional Museum of Cholula |

| Large whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | Ixcaquixtla, state of Puebla | – | – | 1.6f | Cook de Leonard (Reference Cook de Leonard1957: fig. 55a, b) |

| Small whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | Ixcaquixtla, state of Puebla | – | – | 1.6g | Cook de Leonard (1957: fig. 55b) |

| Whistle vase with primatomorphic figure | “said to be from Mitla” (Kidder et al., Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946: fig. 197) in “Oaxaca (?)”(Kidder et al., Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946: 191, fig. 78) | – | Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, USA | 1.6h | Kidder et al. (Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946: fig. 197)a |

| Whistle vase with monkey | Escuintla, Guatemala | 450–650 CE | Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA (M.2010.115.800) | 1.7b | O’Neil (Reference O’Neil2018) |

a Next to the illustration of this whistling vessel, Kidder et al. (Reference Kidder, Jennings and Shook1946: 191, fig. 78) presents another illustration of a seated monkey from Las Colinas, state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. However, it does not indicate its style or associated culture.

Figure 1.6 Pottery of Teotihuacan influence with primate representations from sites south of the Teotihuacan valley.

Figure 1.7 Depictions of (a) a seated monkey on a double vase from Teotihuacan and (b) orange slipped Teotihuacan-like whistling vessel with a monkey from the Mayan region).

1.2.2.2 Murals

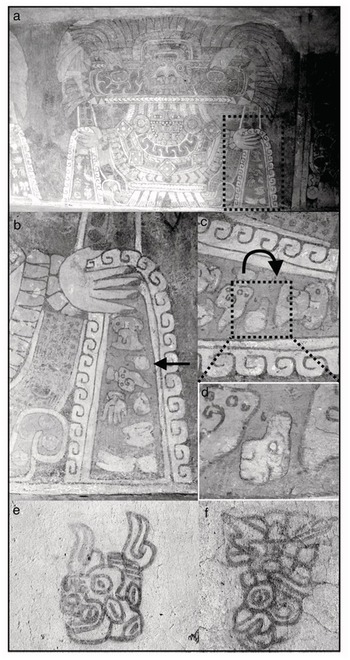

The murals of Tetitla are characterized by presenting animal profiles, with the peculiarity of being located on the wall edges and near the ground (Miller, Reference Miller1973). From that corpus of mural paintings, Langley (Reference Langley1986) includes in his compendium of Teotihuacan notational signs, the design of a head that looks like a primate, indicating that it “bears a resemblance to depictions of animals identified as monkeys” (Langley, Reference Langley1986: 265). In doing so, the author refers to Miller’s work (Reference Miller1973: 148, fig. 310). The representation of the monkey has a prognathous face, a platyrrhine nose, pronounced forehead, a rounded eye and a primatomorphic “mask.” The mural with the aforementioned monkey is called the “Goddess of Jade” or Tláloc Verde [Green Tlaloc] and is located in the northern side of the complex in the portico 11 of the structure 2 of Tetitla (de la Fuente, Reference de la Fuente and De la Fuente1996b). Figure 1.8a presents a panoramic view of the mural and the small representation of the primate found there. The image of the goddess with the monkey is at the far right of the whole fresco – from the perspective of the observer – in the building where four similar goddesses were painted (Fig. 1.8a). A detail of the fauna represented and falling from the left hand of the studied goddess shows the outline of the head of a monkey (Fig. 1.8b). Figure 1.8c shows the head of the monkey which is now degraded: only its outline can be seen today without the internal delineations that represent the monkey’s face. Figure 1.8d shows the same photograph as in Figure 1.8c but with our digital reconstruction of the face of the primate superimposed as photographed in February 1971 by Miller (Reference Miller1973: 148, fig. 310).

Figure 1.8 Teotihuacan frescos with monkey representations. (a) mural with a Jade goddess from Tetitla; (b) detail of the right side of the Jade goddess; (c) current detail of the monkey head profile, turned to the right for a better appreciation, without the internal delineation of the monkey face (photograph taken on June 15, 2018); (d) previous photograph’s digital reconstruction of the monkey face after Miller (Reference Miller1973: 148, fig. 310. Illustration by F. Botas); (e) monkey with “flames” from La Ventilla; (f) possible monkey with earflap from La Ventilla.

At La Ventilla, Cabrera-Castro (Reference Cabrera-Castro and de la Fuente1996) reported two representations of monkeys on the floor of the structure known as the Plaza de los Glifos [Plaza of the Glyphs]. The floor area (7.5 × 11.7 m) is decorated with more than 40 glyphs in red paint on a reticulated area. This is a rare context for painted glyphs to be found but has been found in a few other places in Tetitla and La Ciudadela (Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro and de la Fuente1996). The first is a monkey profile with a felid nose and mouth as well as “flames” emanating from its head (Fig. 1.8e; Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro and de la Fuente1996). This representation is relatively similar to a stone carving found in Teotihuacan (Fig. 1.5h) and the so-called 9 Monkey from Oaxaca (Fig. 1.9c). A second painting is an apparent monkey profile with an earflap and rounded eye (Fig. 1.8f; Cabrera-Castro, Reference Cabrera-Castro and de la Fuente1996). The two paintings are found at similar positions in opposite corners of the room.

Figure 1.9 (a–g) Primate representations in archaeological sites of the state of Oaxaca (Images not to scale; sources in the text. Illustrations by F. Botas); (h) Monkey in Xochicalco’s Temple of the Quetzacoatl, Morelos state; (i) Detail of Xochicalco’s monkey.

1.3 Discussion

Among the elements that suggest the representation of monkeys in the Teotihuacan material culture are the presence of prehensile tail, prominent forehead, primatomorphic “masks,” superciliary arches, prominent belly, noses with separated nostrils, and prognathous face. Primate species are difficult to be full determined in these representations, although, those depicted in whistle vases are similar to spider monkeys. Not all representations of primates in Teotihuacan have been found as offerings or in symbolic contexts. However, Séjourné (Reference Séjourné1966c) suggests that unlike the representation of birds and canids, that of primates seems to have a symbolic meaning, including the association with Quetzacoatl (Feathered Serpent), the god of wind, fertility, light, and wisdom. One of the discoveries of primate remains was in a burial in the Pyramid of the Moon which is related to individuals of possible Mayan origin. The primate found in the Plaza of the Columns might also be related to the Mayans. The other confirmed primate element was found in Xalla, an area used for governing the city of Teotihuacan. There are characteristics that link the primate remains of spider monkeys: (1) two were incomplete buried individuals, but isolated elements (Xalla and Pyramid of the Moon), and an entire skeleton (Plaza of the Columns); (2) in the case of Xalla and the Pyramid of the Moon, they were captured as young animals in regions with wild populations or bred in captivity (generally pet Ateles are more viable than Alouatta); (3) they had ritually oriented use – possibly the bones themselves had such cultural values; and (4) they were linked to the ruling elite. This link is also supported by the fact that the representations of primates in the region and the largest collection of primatomorphic material culture found in a Teotihuacan site were in the vicinity of the Tetitla Palace.

The Mayan and Zapotec cultures began their historical development almost simultaneously in tropical zones: the first in the extreme southeast and the second in the southern zone (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hansen, Pérez, Manzanilla and López2014; Wiesheu, Reference Wiesheu, Manzanilla and López2014). In Teotihuacan, there are elements of material culture (frescoes and ceramics) that resemble features from Tlaxcala, Chupicuaro, as well as Puebla, Oaxaca, and the Mayan region (Angulo-Villaseñor, Reference Angulo-Villaseñor and Ruiz-Gallut2002; Gomez-Chávez, Reference Gómez-Chávez and Ruiz-Gallut2002). In addition, outside the Teotihuacan valley, Kolb (Reference Kolb1987) refers to the exchange with the coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico as well as the Pacific region. Daneels (Reference Daneels and Ruiz-Gallut2002) reviews Teotihuacan elements in Gulf sites such as Matacapan (a commercial enclave), in addition to other localities, such as the river basins of Nautla (Pital), Tecolutla (El Tajin), Papaloapan (Cerro Las Mesas), Coaxtla (La Joya), and Los Tuxtlas (Matacapan). Primatomorphic objects were found in the Neighborhood of the Merchants which is related to the peoples of the Gulf region (Fig. 1.4g, h), as well as a Teotihuacan tripod with a primate, in present-day state of Veracruz. Paddock (Reference Paddock1972) also suggests the presence of Teotihuacan elements in the Monte Albán region and the Maya area of Uaxactún. Chronologically, it is during the Xolalpan period (450–650 CE) that Teotihuacan is perceived as a valley of great influence in the center of Mexico and surrounding regions (Matos-Moctezuma, Reference Matos-Moctezuma1990). Based on this, it is understandable that many of the animal icons that formed the basis of their religion were typical from the tropics: jaguars (N. Sugiyana, Reference Sugiyama2014) and quetzals (Aguilera, Reference Aguilera and Ruiz-Gallut2002; Kubler, Reference Kubler1972a), as well as others like the monkeys. The concentration of these cultural foci in the southern parts of the Mexican territory did not prevent their influence from reaching places like the center, as in Teotihuacan. Teotihuacan inherited characteristics of the preceding societies and those that contemporaneously shared with it the Mesoamerican territory. So the basic guidelines on their relationship with nature did not change fundamentally; however, it is clear that human–animal interactions occurred with adjustments depending on the region where the city was located, and the cultures with which it was related. Starting from these bases, it is clear that within the Teotihuacan pantheon of animals there were many from tropical habitats with symbolic relevance as is the case of monkeys. Moreover, there seems to be a notion of the similarity and liminality among Teotihuacans as can be inferred from the similarity of representation of nonhuman primates and humans in Tetitla (as in two primates from the L. Séujourné collection [Figs. 1.3b, c in this study] and Childs-Rattray [Reference Childs-Rattray2001: 541, figs. 133a, b]).

The representation of primates in Mesoamerica, and particularly among the Maya, has generated special interest since the beginning of the last century (Preuss, Reference Preuss1901) until the present (Baker, Reference Baker1992, Reference Baker2013; Nájera-Coronado, Reference Nájera-Coronado2012, Reference Nájera-Coronado, Millones and López-Austin2013, Reference Nájera-Coronado2015, Reference Nájera-Coronado and Ruz-Sosa2016; Rice and South, Reference Rice and South2015; South, Reference South2005). It was suggested that monkeys were partially represented in the Classic Maya period (300–900 CE). They have been studied with the aim of determining which species of primate has been represented in the Maya archaeological iconography (Baker, Reference Baker1992, Reference Baker2013; Rice and South, Reference Rice and South2015; South, Reference South2005). Nájera-Coronado (Reference Nájera-Coronado2012, Reference Nájera-Coronado2015) also suggests that in the Maya society, primarily in the Late Classic (550–900 CE), primates played a fundamental role in their association with cocoa, which is possibly the most revered botanical item after corn. Monkeys might have a fundamental role in the framework of mythical Mayan thought. Nájera-Coronado (Reference Nájera-Coronado, Millones and López-Austin2013, Reference Nájera-Coronado and Ruz-Sosa2016) locates the primates on the edge of humans with animals. The monkey is an animal that provides symbolic meanings, such as its association with the sun and wind, libido, and writing. In addition, primates were characterized by their particular intelligence up to their role as an entity that represents fertility (Braakhuis, Reference Braakhuis1987; Bruner and Cucina, Reference Bruner and Cucina2005). As for pre-Hispanic osteoarchaeological remains of primates in the Mayan area, there are elements from the Yucatan peninsula in Itzamkanac (a humerus, Terminal Classic, 900–100 CE) and Yaxuná (an ulna, Pre-Postclassic 500 BCE to 1600 CE) (Valadez, Reference Valadez, Sandoval-Hoffmann, Sandoval-Martínez and Saínz2014). In both cases, postcranial remains, attributed to Ateles geoffroyi, are represented in food waste deposits (Valadez, Reference Valadez, Sandoval-Hoffmann, Sandoval-Martínez and Saínz2014). Looking further south, Pohl (Reference Pohl1976) indicates the presence of Post-classic locations in Flores and Tikal, as well as spider monkeys in Tikal (Post-classic) and in Seibal (late Classic). In Tikal, a complete skeleton of a spider monkey was found in an early Classic chultun tomb (Moholy-Nagy, Reference Moholy-Nagy and Emery2004). In the Guatemalan site of Seibal, Pohl (Reference Pohl and Willey2004) also reports howler monkeys (Alouatta) and spider monkeys (Ateles) in its late Classic deposits. On the other hand, remains of howler monkeys have been found in the Mayan site of Selín Farm in the Ulúa valley in Honduras (Henderson and Joyce, Reference Henderson, Joyce and Emery2004). Emery and Thornton (Reference Emery and Thornton2008) indicated that colorful birds, large felids, and primates might have been particularly prized among the Mayan.

In Mayan regions, such as Piedras Negras, there is evidence of the relationship of the Teotihuacan people and their Tlaloc with prominent members of the Peten Maya on a lintel (Angulo-Villaseñor, Reference Angulo-Villaseñor and Ruiz-Gallut2002). The relations between Teotihuacan and the sites of Kaminaljuyu, Copán and Tikal appear in the Early Classic period (Fash, Reference Fash and Ruiz-Gallut2002). Sugiyama and López-Lujan (Reference Sugiyama, López-Lujan, Sugiyama and López-Lujan2006a) refers to a strong connection between the ruling elites of Teotihuacan and the Mayan, at least from the fourth century CE. In research that explores the relationship between Teotihuacan and the Mayan region, Laporte-Molina (Reference Laporte-Molina1989) indicates that Uaxactun was ruled by the Ma’Cuch lineage by 380 CE, and also had a relationship with Tikal (Coe, Reference Coe1972). As remarked by Sugiyama and López-Lujan (Reference Sugiyama, López-Luján, López-Luján, Carrasco and Cué2006b), Kaminajuyu is a site with links with Teotihuacan and has elite “lotus flower” burials. In this sense, the sites of Kaminajuyu and Uaxtactun present burials that resemble Burial 5 of the Pyramid of the Moon, in the treatment of their ruling elites. Burial 5 is the site where postcranial remains have been found, as in the Mayan sites of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Laporte-Molina (Reference Laporte-Molina1989) reviews the presence of material culture from the Mayan area in Teotihuacan, and indicates the existence of Mayan pottery in La Ventilla A and Xolalpan burials as well as in the site of the so-called Mayan Murals of Tetitla with Mayan-like jade pieces. For instance, Tetitla is located 600 m west of the Street of Death that links both Teotihuacan pyramids (Taube, Reference Taube and Braswell2004). Tetitla is the structure that preserves more paintings southwest of Teotihuacan. Green goddesses are represented in this complex (Ruiz-Gallut, Reference Ruiz-Gallut and De la Fuente1999), one of them with a monkey representation. Taube (Reference Taube and Braswell2004) indicates that Tetitla cannot be considered a Mayan neighborhood, although it presents evidence of material culture, such as murals and movable objects, as well as Maya phonetic texts suggesting interactions of particular relevance. The murals of Tetitla have “foreign” features according to Ruiz-Gallut (Reference Ruiz-Gallut and Ruiz-Gallut2002). A primatomorphic vessel was found at the Mayan-related site of La Ventilla (Fig. 1.5e) as well as paintings on the floor structure (Fig. 1.8e, f). For this vessel it was suggested that “a cylindrical duct connects the simian character to the vase; the body of the monkey being hollow, when filling the vase of water, this last passes through this conduit and flows into the animal, which causes a hissing. The monkey is associated with the divinity of the Wind; this type of vase was probably used during ceremonies related to this phenomenon” (Solís, Reference Solís2009: 348). A vessel from Escuintla, Guatemala (Fig. 1.7b) is similar to others found in the Teotihuacan valley and surrounding central Mexican regions (Figs. 1.5e–f; 1.6d, f–h). This represents an example of the circulation of Teotihuacan primate imageries in the Mayan region. Therefore, the presence of primates in Teotihuacan could be, in part, related to the presence of populations of Mayan origin in the City of the Gods. Primates are present in elite burials (such as Burial 5 of the Pyramid of the Moon), the only primates in Teotihuacan murals (Tetitla and La Ventilla), the largest collection of primatomorphic Teotihuacan pieces – also recovered in Tetitla – and the alleged evocation of the divinity of the wind in of the vessel from La Ventilla (Solís, Reference Solís2009). The latter is a characteristic that has been associated with primates and their connection with the Maya (e.g. Nájera-Coronado, Reference Nájera-Coronado2015).

Not only Uaxactun and localities of southern Guatemala (Zaxualpa, Amatitlan, and Kaminaljuyu) had relationships with areas of influence of Teotihuacan but also Monte Albán as well as other sites in present-day state of Oaxaca (Matos-Moctezuma, Reference Matos-Moctezuma1990). There is a clear relation of Oaxacans and the Zapotecs of Monte Alban with Teotihuacan; stylistic similarities existed in the material culture, as in the case of urns, particularly between 500 BCE and 700 CE (Berlo, Reference Berlo1984). On the other hand, in the Oaxacan Neighborhood of Teotihuacan, Zapotec-style pottery made with local clay was found (Taube, Reference Taube and Braswell2004). Winter et al. (Reference Winter, Martínez-López, Herrera-Muzgo and Ruiz-Gallut2002) reviewed existing information on the relationship of Monte Albán and Teotihuacan, and commented on the shared elements of the Oaxacan neighborhoods of Teotihuacan with the Oaxacan Preclassic localities, as follows: (1) the material culture of the Oaxacan Cerro de la Minas has a clear Teotihuacan influence; (2) excavations on the Monte Albán platforms shows Teotihuacan cultural elements; (3) there are stelae on the southern flank of the Monte Albán platform where the Teotihuacan–Oaxaca relationship is recorded; (4) there is possible Zapotec archaeoastronomic linkage with the configuration of Teotihuacan; and (5) there are possible similarities in the configuration of red discs in Zapotec and Teotihuacan buildings. Regarding archaeoprimatological aspects, Kubler (Reference Kubler1972b) lists monkeys as one of the 22 animal motifs represented in Teotihuacan iconography in dated ceramics and describes Teotihuacan zoomorphic representations as more austere than those of the Mayan region, and at the same time, they represent an additional element that links them with those of Monte Albán.

Considering this information, in the state of Oaxaca, figurines representing monkeys have been found at Carrizal, a site located near Ciudad Ixtepec, a region where natural populations of A. geoffroyi are closely located (Ortiz-Martínez and Rico-Gray, Reference Ortiz-Martínez and Rico-Gray2005). Also in the Oaxacan site of San José Mogote, figures identified as spider monkeys, with frontal crests, rounded eyes, and prognathic faces, have been reported (Fig. 1.9a; Marcus, Reference Marcus1998). At the same site, a skull of a spider monkey with red pigment cover has been recovered (Marcus, Reference Marcus1998). The “spider monkey skull had been placed (as an offering) under the plaster floor of a ‘men’s house’ [Casa de Varones]. That [small] ritual building [on Mound 1] had been largely destroyed by later buildings constructed above it. There were many meters of heavy earth above the skull. The skull was crushed by the enormous weight. [They were] bone fragments coated both in (ritual) red pigment and white lime plaster (from the floor). Only when we began to clean the fragments in the laboratory did we see its teeth and realize that it was an exotic animal” (J. Marcus, 2018: pers. comm.). Thus, it is relevant to notice that the primate element from Xalla was also recovered under a plaster floor. On the other hand, there is also a Ñuiñe urn (now deposited in the Regional Museum of Huajuapan) with a representation of a seated monkey holding a bowl (Fig. 1.9b). This urn/censer comes from the Cerro de la Minas in the Lower Mixteca, is classified as typical of the Epiclassic period (600–900 CE);, and has stylistic similarities to those urns of Teotihuacan. Ortiz-Maciel and Serrano-Rojas (Reference Ortiz-Maciel and Serrano-Rojas2016) indicate that this ancient society seems to have followed the representative characteristics of Teotihuacan and Monte Albán.

In Monte Albán, state of Oaxaca, there are also three pieces of particular Teotihuacan interest, now deposited in the National Museum of Anthropology. The first is a vase from Atzompa (Monte Albán IIIA, early Classic) dated from 200 to 500 CE. This piece represents “13 Monkey,” typical of the calendar system of central Mexico (Fig. 1.9c). This monkey is similar to the one found in Teotihuacan and considered a deity (Fig. 1.5h). Also, from the early Classic period there are ceramics that look like similar to the ones of the Teotihuacan style within the territory ruled by Monte Albán (Fig. 1.9d, e). In this Oaxacan pre-Hispanic city, Marcus (Reference Marcus2008; see also: Acosta, Reference Acosta1958–1959; Piña-Chan, Reference Piña-Chan1993) referring to one of the main structures of the Monte Albán complex, comments that:

The Stela 1, in the northeast corner of the platform, shows the ruler 12 Jaguar sitting on his throne; it is wearing a jaguar suit and carries a spear. The associated hieroglyphic text refers to his divine ancestry, his pilgrimages and his divinations. Hidden on the underside of Stela 1 are representations of four ambassadors, one of which (called ‘9 Monkey’) appears coming out of a temple decorated in the style of several Teotihuacan temples. This scene has been interpreted in the sense that ‘9 Monkey’ traveled from Teotihuacan. There is a more elaborate version of this ‘diplomatic’ scene engraved on the underside of another stela, the ‘Estela Lisa’ (in the northwest corner of the platform). In both Stela 1 and Lisa Stela the ambassador who appears retreating from a Teotihuacan-style temple bears the name 9 Monkey.

Marcus (Reference Marcus2008) also pointed out that the Teotihuacan ambassadors may have participated in the dedication of the Southern Platform. This reference shows not only the close relationship between Monte Albán and Teotihuacan during the Classic period but also reveals the presence of the name of a monkey as part of the Teotihuacan diplomatic entourage at Monte Albán. That is to say, the primatological referent was implicit in the denomination of a diplomatic agent of the Teotihuacan elite, who traveled from a region without autochthonous populations of primates to another that does harbor primates. Furthermore, Marcus (Reference Marcus, Flannery and Marcus1983) commented that the structures associated with the 9 Monkey in the lower part of Stela 1 (Fig. 1.9f) and the Stela Lisa (Fig. 1.9g) of Monte Albán are similar to those of the Tetitla site in Teotihuacan (see Fig. 1.8e, f). In this connection, Marcus (Reference Marcus, Flannery and Marcus1983: 179) suggests that it “seems reasonable to propose that the individual 9 Monkey came from Teotihuacan, if not from the actual Tetitla precint, which lies only 2 km from the Oaxaca barrio at Teotihuacan.” It should be noted that in Xalla, an area used by the ruling elite and located on an esplanade just between the pyramids of the Sun and the Moon of Teotihuacan, there is not only the presence of artisans destined to produce for the rulers, but also of large quantity of mica plates brought from Oaxaca (Manzanilla, Reference Manzanilla2017a, Reference Manzanilla and Robbb).

As for the allochthonous Teotihuacan animals, such as jaguars (Panthera onca) (Valadez, Reference Valadez1992) or red brocket deers (Mazama americana) (Valadez et al., Reference Valadez, Rodríguez, Christian, Silva, Manzanilla and Valadez2017), appear as isolated elements, in most cases, even with characteristics that indicate that they are not just “bones that survived time,” but as objects that were intentionally prepared to be used in that way (Manzanilla and Valadez, Reference Manzanilla and Valadez2017; Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2010; Rodríguez and Valadez, Reference Rodríguez, Valadez, Götz and Emery2014; Valadez, Reference Valadez1992, Reference Valadez and Manzanilla1993). Under this perspective, the idea of the use of the symbolic force of a species is strongly supported. This could be the case for the primate bone remains at the Pyramid of the Moon, which could have a ritual meaning as inferred by its location and contextualization. On the other hand, the partial mandible of Xalla, displays porosity that seems similar to that observed in captive animals, and it was from a juvenile spider monkey, suggesting it might have been captured to be kept as a pet linked to the ruling elite (also a possible monkey pet with a rope in a Teotihuacan-style whistle vase from Puebla: Fig. 1.6f). In addition, the primate remains from Teotihuacan have a possible emblematic value as being buried with members of the Teotihuacan elite (e.g. Valadez, Reference Valadez, Sandoval-Hoffmann, Sandoval-Martínez and Saínz2014). As indicated by López-Austin (Reference López-Austin1984), for the Postclassic period, infants were considered relevant supernatural resources that had the ability to communicate with the gods. The author also pointed out that the arm was considered as a body part related to executional and manipulative capabilities, with the left arm having special supernatural leverage and authority. The fact that primates associate with places linked to foreign human communities, such as the people of the Gulf (Merchants’ Quarter), Mayan people (Burial 5 of the Pyramid of the Moon, Plaza of the Columns, Tetitla, and La Ventilla), or the Oaxaca region (Xalla), could be supportive of the argument that monkeys were adopted as symbolic “commodities” in the central metropolis of Teotihuacan. On the other hand, the presence of primatomorphic cultural material produced in Teotihuacan artisan neighborhoods, allowed the mobility of these pieces and images within the city, and may have had a figurative meaning among the inhabitants of this valley. Considering the foregoing, it is clear that primate remains and material culture are scarce considering the extent of the city and the long period when it has been archaeologically studied. However, it was of particular interest to explore how primates circulated and were appropriated in the City of Gods, particularly among the ruling elite (Pyramid of the Moon, Xalla, Plaza of the Columns, Tetitla, La Ventila, Zacuala), as well as looking at how they arrived in this valley from distant lands, and overall how they also travelled with their burden of aesthetic and cultural values to other distant regions with Teotihuacan influence and relations such as present-day Puebla, Oaxaca, and distant Guatemala. To conclude, after the fall of the City of Gods, during the Epiclassic (560–900 CE), peoples from Teotihuacan, as well as the Mayan and coastal regions might have inhabited the city of Xochicalco, in modern Morelos state (e.g. Litvak-King, Reference Litvak-King1970; Webb, Reference Webb and Browman1978). In this city, the main structure, the Temple of Quetzacoatl, bears a conspicuous primate engraving in a central position (Fig. 1.9h, i) – a signal of the past role of primates in ancient central Mexican societies.