Childhood adversity

Childhood adversity refers to experiences that pose a threat to a child's physical or psychological well-being. Childhood adversity is common, with over half of children in Western societies having experienced at least one type of adversity.Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor1–Reference Fanslow, Hashemi, Gulliver and McIntosh3 Childhood adversity is the focus of growing multidisciplinary interest, and it is therefore necessary to be clear about its definition. Childhood adversity is an inclusive term, and encompasses childhood maltreatment,Reference Corso, Edwards, Fang and Mercy4 childhood traumaReference Briere, Kaltman and Green5 and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6 Childhood adversity refers to a broad range of factors, including abuse, household dysfunction, social problems, financial hardship and parent instability or mental health problems.Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield and Perry7,Reference Marotta8 Exposures to childhood adversity are highly interrelated, and the more adversity a child has experienced, the higher their risks of experiencing further adversities.Reference Mclaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler9 The effects of these exposures accumulate in a dose-dependent pattern, so that with every added exposure of adversity that a child experiences, the worse their predicted outcomes are. Researchers studying childhood adversity now widely agree that effects vary based on the number of adversities that an individual experiences over childhood, rather than the nature or intensity of the adversities.Reference Briere, Kaltman and Green5,Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6

There is an increasing body of literature describing the deleterious outcomes that follow cumulative childhood adversity exposure. A systematic review by Hughes et alReference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton10 summarises the wide-reaching health outcomes, including poor self-rated health, cancer, heart disease, respiratory disease, mental ill health and substance misuse. It also describes the strong association with social factors such as interpersonal and self-directed violence. Childhood adversity is therefore an area for great concern, given its cumulative effects on such a wide array of domains of adult functioning. Consequently, research has turned to identifying protective factors that reduce the burden of childhood adversity.

Protective factors

Protective factors following childhood adversity exposure can be considered within the wider domain of resilience. The study of resilience aims to identify determinants of positive adaptation following exposure to adversity.Reference Rutter11 There are many ways of defining resilience.Reference Cosco, Kaushal, Hardy, Richards, Kuh and Stafford12,Reference Rudd, Meissel and Meyer13 Historically, it has been considered a stable trait that describes those who flourish despite adversity, and who could therefore be considered somewhat ‘invulnerable’ to life's stresses. This definition has since evolved to view resilience as a process of positive adaptation, involving the dynamic interaction between the individual and their environment.Reference Rudd, Meissel and Meyer13 The theoretical underpinnings of resilience are complex, and can be applied differently in different fields. Two components are key to operationalising the process of resilience: adversity and positive adaptation.

The present systematic review seeks to summarise protective factors that have been found to promote positive adaptation following cumulative childhood adversity. There has been a considerable increase in literature in this area in the 25 years since the seminal ACEs studyReference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6 that described the cumulative effects of childhood adversity. Despite increased knowledge and interest in the pathways through which the accumulation of childhood adversity confers vulnerability to negative adult outcomes, no known reviews have systematically examined the literature on protective factors that may decouple the relationship between cumulative childhood adversity and negative adult outcomes.

Prior research

Two prior reviews have summarised protective factors following childhood adversity. Aafjes-Van Doorn et alReference Aafjes-Van Doorn, Kamsteeg and Silberschatz14 summarised cognitive factors that either increased or decreased risk for adult psychopathology. Importantly, they noted that not all individuals who experience multiple childhood adversities develop psychopathology. This review highlights key risk and protective mechanisms by which childhood adversity is related to adult psychopathology. However, this review only includes cognitive protective factors, and excludes environmental factors that are important for identifying targets for intervention. The systematic review by Fritz et alReference Fritz, de Graaff, Caisley, van Harmelen and Wilkinson15 investigated protective factors between childhood adversity and psychopathology. They found a range of protective factors at individual, family and community levels. This review indicates the broad range of protective factors for psychopathology outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity, although outcomes were restricted to those aged 13–24 years, as opposed to adulthood.

There have also been various systematic reviews investigating protective factors between cumulative childhood adversity and physical health outcomes,Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton10,Reference Holman, Ports, Buchanan, Hawkins, Merrick and Metzler16–Reference Oh, Jerman, Silvério Marques, Koita, Purewal Boparai and Burke Harris19 and this area is well reported on. There is, however, a lack of review examining protective factors following cumulative childhood adversity for the broad variety of adult outcomes beyond physical health, and specifically early psychopathology.

Present study

The present study aims to address these gaps by systematically reviewing the literature on protective factors for psychosocial adult outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity. This review will focus on protective factors for cumulative childhood adversity exposure rather than the individual effects of specific adversities, and we have defined cumulative childhood adversity as exposures in multiple domains. The scope of the present study is to identify factors associated with positive adaptation following adversity, therefore we will include only protective factors measured after adversity. This review takes a broad approach to build on findings from previous research, recognising that the likely protective factors will fall into the physical, social, environmental or psychological domains.Reference Lorenc, Lester, Sutcliffe, Stansfield and Thomas20 The pathways to physical health outcomes have been well researched and reviewed, whereas the psychosocial sequelae of cumulative childhood adversity have not, and for this reason, physical health or biological mediators and outcomes are omitted from this review.Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton10,Reference Holman, Ports, Buchanan, Hawkins, Merrick and Metzler16–Reference Oh, Jerman, Silvério Marques, Koita, Purewal Boparai and Burke Harris19 This systematic review aims to identify social, psychological and environmental variables that act as protective factors, leading to positive adaptation to psychosocial outcomes in adulthood following cumulative exposure to childhood adversity.

Method

This review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; see Supplementary Appendix 5 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.561 Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow21), and the protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; identifier CRD42021237510). As this review is concerned with observational studies, to ensure rigor, the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed.Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie22 Because of concerns about heterogeneity in the final articles, the meta-analysis was abandoned. Reflecting this change in direction, there are amendments to the registered protocol. A full breakdown is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Search strategy

In conjunction with a research librarian, investigators electronically searched Medline, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science, on 11 February 2021. Details of the databases and search strategies for each database are presented in Supplementary Appendix 2. There was no limit set on start date. The search strategy was designed to find longitudinal studies examining childhood adversity and adulthood outcomes. In addition, investigators reviewed reference lists of included papers. The search was rerun on 9 August 2022, to identify additional potentially relevant studies.

Search strategies were designed to find peer-reviewed, longitudinal investigations of intervening factors that were social, environmental or psychological, measured following cumulative childhood adversity, which resulted in positive adaptation in adult outcomes that were social, psychological, occupational or related to mental health and well-being. Cumulative childhood adversity was defined as exposure to more than one domain of adverse experience before 10 years of age. Because of the number of studies investigating abuse exposure, psychological, emotional, physical and sexual abuse were considered to be one domain, with neglect as a separate domain. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Hierarchy of inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria

There were some amendments to the proposed eligibility criteria, most of which were determined after an initial screen of ten percent of abstracts. These can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

We included studies that assessed childhood adversity cumulatively, with a valid measure (such as the ACE score),Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6 and investigated an intervening factor (such as a mediator or moderator) that was social, environmental or psychological. This factor must have conferred statistically significant change on the pathway from cumulative childhood adversity toward a more favourable adult outcome, representing positive adaptation. In other words, factors could have had a negative relationship with an unfavourable outcome, or a positive relationship with a favourable outcome. The favourability of the outcome was as defined by the authors as being beneficial to social, psychological or occupational functioning or mental health and well-being in adulthood. If it was not defined by the authors, two reviewers (M.B. and G.W.) independently judged favourability, any disagreements were discussed and a third reviewer (G.N.-H.) was available for the final decision. We included only studies reporting a statistic (such as an odds ratio or other measure of effect size) that compared the outcomes of groups based on exposure to an intervening factor, the possible protective factor, following cumulative childhood adversity. No restrictions on the year or location of publication were specified; however, only English language abstracts were able to be screened. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1.

Evidence acquisition

Literature search results were uploaded to Covidence (version 2.0; Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; see www.covidence.org), a software package designed for screening of resources for systematic reviews.23 Two investigators (M.B. and G.W.) independently screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria (Table 1). All possible studies were acquired and read in full by two authors (M.B. and G.W.) to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Any articles for which there were conflicts were discussed, and conclusions were determined by consensus.

Data extraction

Data were double extracted, first by author M.B. (on 1 November 2021 for first screen and 15 September 2022 for the rerun screen) and then by investigators Z.M. and G.N.-H. It was checked for consistency by author G.W. The data extracted included details of the study, participants, adversity, protective factor and outcomes and potential conflicts of the authors. The full list of data extracted is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Fields for data extraction

Evidence synthesis

The initial electronic search identified 2025 potentially relevant articles after excluding duplicates. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart of the article selection, following PRISMA guidelines. The initial search identified 22 papers to include in the review. The second search identified 450 potentially relevant articles, of which six further studies were included in the review. After reviewing study criteria, a total of 28 articles describing 23 cohorts were kept for inclusion.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart of systematic literature search.

If more than one finding in a paper met the criteria for the review, only one finding from each study was reported. The finding reported was chosen based on relevance to other studies (so as to find patterns in protective factors) by consensus, and following that, effect size. If a study reported one finding that fit into a grouping and one that did not, we chose the result that fit the groupings even if the other had a larger effect. If results fitted into more than one grouping, the result with the largest effect size was chosen. If a paper did not report a finding that fit into categories with other papers, it was reported on its own.

Plans for meta-analysis were developed a priori and can be found in the PROSPERO protocol (identifier CRD42021237510). It was decided not to proceed with the meta-analysis. The papers included in the review had underlying conceptual differences in approach (in terms of reasoning of the research and statistical justifications), and were very heterogeneous. For these reasons it was not considered appropriate to meta-analyse even by using statistical approaches to manage some of the heterogeneity.

Risk-of-bias assessment

All included studies were evaluated independently by two reviewers (M.B. and G.W.), using the Methodological Standards for Epidemiological Research (MASTER) tool.Reference Stone, Glass, Clark, Ritskes-Hoitinga, Munn and Tugwell24 Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, and a third reviewer was consulted (G.N.-H.) if consensus could not be reached.

The MASTER tool provides an approach to assessing risk of bias in individual studies that is flexible in its application.Reference Stone, Glass, Clark, Ritskes-Hoitinga, Munn and Tugwell24 As most risk-of-bias tools are designed for randomised controlled trials, they did not fit well with this systematic review design.Reference Sterne, Hernán, Reeves, Savović, Berkman and Viswanathan25 The MASTER tool is a list of 36 methodological safeguards assessing seven domains relating to minimising bias in research studies. The domains are as follows: equal recruitment (items 1–4), equal retention (items 5–9), equal ascertainment (items 10–16), equal implementation (items 17–22), equal prognosis (items 23–28), sufficient analysis (items 29–31) and temporal precedence (items 32–36). For each paper, reviewers judged whether each of the safeguards had been met. The result for an individual paper is a score between 0 and 36, based on the number of safeguards met. The MASTER score is designed to be a comparative tool between papers, and there is no defined score where risk of bias is determined as ‘high’ or ‘low’. A full list of the MASTER safeguards and interpretations for the present study are supplied in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Quality of evidence assessment

The strength of the review's outcome was measured with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) checklist.Reference Murad, Mustafa, Schünemann, Sultan and Santesso26–Reference Bernstein David, Fink, Handelsman and Foote28 This checklist provides certainty ratings that the results of the study are similar to the true effect (very low, low, moderate and high). Observational studies begin on ‘low’ score and are down-rated down based on five categories of outcome quality: risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias. The quality of the outcome can be up-rated if there is a very large magnitude of effect, a dose-response gradient or when residual confounding is likely to decrease rather than increase the magnitude of the effect.Reference Balshem, Helfand, Schünemann, Oxman, Kunz and Brozek27 As the GRADE system is subjective, criteria were applied by discussion among all three reviewers (M.B., G.W. and G.N.-H.). Quality of evidence assessments were only performed for domains containing more than one paper (excluding the domain for multiple protective factors, because of the high heterogeneity between the measures).

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process. The initial search yielded 2025 papers after duplicates were removed. The second screen identified a further 450 papers. After the title and abstract screening, 2276 papers were excluded, leaving 199 papers for full-text screening. This resulted in 28 studies of 23 cohorts, to be included in the final review. The reasons for exclusion are detailed in Fig. 1. The most common reason for exclusion was that the predictor did not meet criteria (i.e. their measure of adversity was not valid, not cumulative, did not concern the period before 10 years of age, etc.). All observed protective effects are presented in an acyclic graph in Supplementary Appendix 6.

Study characteristics

In total, 230 161 individuals were included in the analysis. Studies were published between 2008 and 2022, and were conducted in the USA (17 studies), China (two studies), Norway (two studies), Canada (two studies), Sweden (two studies), The Netherlands (two studies) and the UK (one study). Nine studies prospectively measured childhood adversity (36.4%), and 18 studies retrospectively measured childhood adversity (63.6%). Sample sizes ranged from 108 to 96 399. Study characteristics are summarised in Tables 3–6.

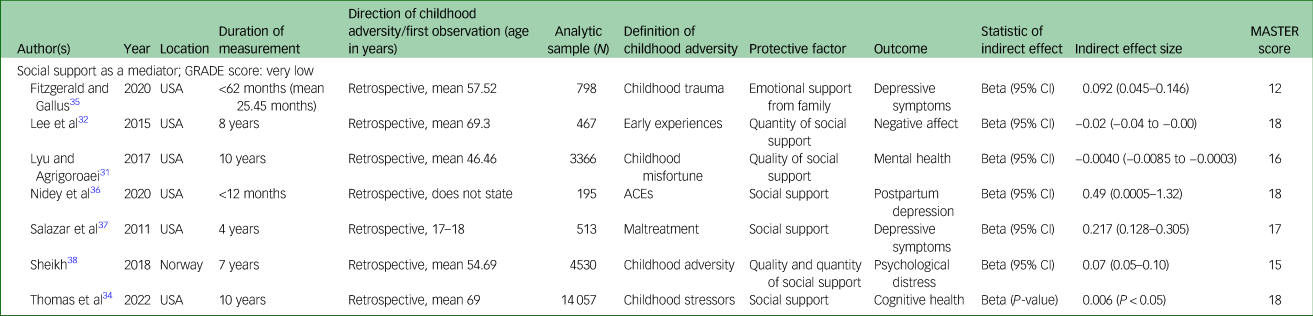

Table 3 Details of included studies examining social support as a mediator

MASTER, Methodological Standards for Epidemiological Research; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations.

Measures of cumulative childhood adversity

The most common measures of childhood adversity were variations on the ACE questionnaire,Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6 followed by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ).Reference Bernstein David, Fink, Handelsman and Foote28 The main difference between these measures is that the CTQ assesses childhood physical, sexual and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect, whereas the ACE measure assesses these factors as well as other indicators of adversity in the home.Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards6,Reference Meinck, Neelakantan, Steele, Jochim, Davies and Boyes29 Both are well used and widely validated. Other measures of childhood adversity were generally latent variables constructed from various experiences of adversity in childhood, and are comparable to the ACE questionnaire and the CTQ.Reference Schmidt, Narayan, Atzl, Rivera and Lieberman30

Outcomes

The outcomes for each paper can be seen in Tables 3–6. All outcomes were measured after 18 years of age, and most papers measured outcomes in young to middle adulthood, although some were measured as late as 75Reference Lyu and Agrigoroaei31,Reference Lee, Aldwin, Kubzansky, Chen, Mroczek and Wang32 or 80 years of ageReference Chen, Fan, Nicholas and Maitland33 and one study reported an age range up to 100 years.Reference Thomas, Williams-Farrelly, Sauerteig and Ferraro34 The most common outcomes were related to mental health (ten papers), namely symptoms of depression (six papers), but also more general measures of mental health (two papers), anxiety (one paper), psychological distress (two papers) and psychiatric care utilisation (one paper). There was one paper that measured hyperarousal symptoms related to post-traumatic stress and one measure of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in general. There were two papers each studying the following outcome domains: general adversity, violent behaviour/maltreatment, socioeconomic outcomes and relationship outcomes. Two papers also looked at cognitive health, and both had similar measures of attention, processing speed and memory.

Protective factors

All papers studied relationships by using mediation analysis. Studies were grouped into domains based on the protective factor. The domains were social support (seven papers), factors related to education and academic competence (eight papers), personality and dispositional factors (eight papers), factors related to romantic relationships (two papers) and scores of multiple protective factors (two papers). There were two papers that had protective factors that did not fit into coherent domains (socioeconomic stability, adolescent adjustment). The characteristics of each study are presented in Tables 3–6.

Social support

The study characteristics for papers examining social support as a protective factor are presented in Table 3. All papers reported beta coefficients that ranged from 0.0024 to 0.49. All studies were retrospective, with data collected on childhood adversity when participants were adults (18–69.3 years of age). Six of the seven studies looked at the effect of social support on outcomes related to mental health, most commonly depressive symptoms. All these papers used different measures for childhood adversity, social support and mental health; however, they are similar enough that this is likely to be a real effect. One paper examined social support as a protective factor between childhood adversity and cognitive health.

Of the papers examining mental health outcomes, there was variability in the focus of social support measures. Although two studies found that general social support was effective,Reference Nidey, Bowers, Ammerman, Shah, Phelan and Clark36,Reference Salazar, Keller and Courtney37 two studies found that social support from families was particularly effective.Reference Lyu and Agrigoroaei31,Reference Fitzgerald and Gallus35 Three studies examined the quality and quantity of social support. Lee et alReference Lee, Aldwin, Kubzansky, Chen, Mroczek and Wang32 found that it was the quantity of support (i.e. the network size) that was effective, whereas Lyu and AgrigoroaeiReference Lyu and Agrigoroaei31 found that quality of social support (i.e. the self-rated feeling of being supported) was most effective. SheikhReference Sheikh38 examined self-rated quality and quantity of social support together, and found that this had a stronger effect than either type on its own. Thomas et al,Reference Thomas, Williams-Farrelly, Sauerteig and Ferraro34 who measured cognitive health outcomes, used a measure of combined social support from a spouse, children, other family and friends.

Factors related to education and academic competence

The study characteristics for papers examining factors related to education and academic competence as a protective factor are presented in Table 4. Effect sizes were presented as odds ratios or beta coefficients. Four of the eight studies examined childhood adversity prospectively, with three measuring this from birth.

Table 4 Details of included studies examining education as a mediator

MASTER, Methodological Standards for Epidemiological Research; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations; ACE, adverse childhood experience.

Two studies measured educational attainment or highest level of education as a protective factor.Reference Almquist and Brännström39,Reference Fernandez, Christ, LeBlanc, Arheart, Dietz and McCollister42,Reference Lin and Chen43,Reference Sheikh45 Björkenstam et alReference Björkenstam, Dalman, Vinnerljung, Ringbäck Weitoft, Walder and Burström41 examined school performance, and Pinto Pereira et alReference Pinto Pereira, Li and Power44 examined cognitive ability. Augustyn et alReference Augustyn, Thornberry and Henry40 examined the likelihood of dropping out of high school. Chen et alReference Chen, Fan, Nicholas and Maitland33 examined years of school attainment.

Each study found that education or academic competence was an effective protective factor for a different outcome from cumulative childhood adversity. Three studies found that education was a protective factor for mental health outcomes following childhood adversity: it was protective for psychiatric care utilisation in the study by Björkenstam et al,Reference Björkenstam, Dalman, Vinnerljung, Ringbäck Weitoft, Walder and Burström41 for psychological distress in the study by Sheikh,Reference Sheikh45 and for symptoms of depression in the study by Chen et al.Reference Chen, Fan, Nicholas and Maitland33 Two studies found that education was a protective factor for occupational/financial outcomes from childhood adversity, namely occupational prestigeReference Fernandez, Christ, LeBlanc, Arheart, Dietz and McCollister42 and financial insecurity.Reference Pinto Pereira, Li and Power44 Augustyn et alReference Augustyn, Thornberry and Henry40 found that education was a protective factor for maltreatment perpetration. Almquist and BrännströmReference Almquist and Brännström39 found that education was a protective factor for reducing an adult adversity score, which included social assistance recipiency, unemployment and mental health. Lin and ChenReference Lin and Chen43 found that education was a protective factor for cognitive health outcomes following childhood adversity.

Personality and dispositional factors

The study characteristics for papers examining personality and dispositional factors as protective factors following childhood adversity are presented in Table 5. Three papers measured childhood adversity prospectively, and the others were retrospective.

Table 5 Details of included studies examining personality and dispositional factors as a mediator

MASTER, Methodological Standards for Epidemiological Research; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations; ACE, adverse childhood experience; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Effective protective factors were expectations for the future,Reference Brumley, Jaffee and Brumley46 mastery,Reference Lee, Phinney, Watkins and Zamorski49 self-awareness,Reference Maas, Laceulle and Bekker50 openness to experience,Reference Pos, Boyette, Meijer, Koeter, Krabbendam and de Haan51 dispositional optimism,Reference Chen, Christ, Shih, Xie, Grider and Lewis47 self-esteemReference Kim, Lee and Park48 and self-regulation.Reference Rollins and Crandall52 These factors were found to be protective factors for violent behaviour,Reference Brumley, Jaffee and Brumley46 mental health,Reference Chen, Christ, Shih, Xie, Grider and Lewis47–Reference Lee, Phinney, Watkins and Zamorski49, Reference Rollins and Crandall52 hyperarousal symptomsReference Maas, Laceulle and Bekker50 and life events,Reference Pos, Boyette, Meijer, Koeter, Krabbendam and de Haan51following childhood adversity.

The group of papers demonstrates that many intrapersonal factors act as buffers to the effects of cumulative childhood adversity. Self-awareness and mastery were protective factors for mental health symptoms. Expectations for the future, which included both expectations of attending college and expectations of being killed by age 21 years, was a protective factor for violent behaviour following childhood adversity. Openness to experience mitigated life events following childhood adversity.

Romantic functioning

Two papers found that factors related to romantic relationships mitigated the effects of cumulative childhood adversity on adulthood relationships. Labella et alReference Labella, Raby, Martin and Roisman53 found that romantic competence was a protective factor for adult supportive parenting following childhood adversity. Vaillancourt-Morel et alReference Vaillancourt-Morel, Rellini, Godbout, Sabourin and Bergeron54 found that relationship intimacy was a protective factor for relationship satisfaction following childhood adversity.

Latent variables of multiple protective factors

Banyard et alReference Banyard, Williams, Saunders and Fitzgerald55 and Giovanelli et alReference Giovanelli, Mondi, Reynolds and Ou56 both found that latent scores of multiple protective factors mitigated outcomes associated with childhood adversity. In the paper by Banyard et al,Reference Banyard, Williams, Saunders and Fitzgerald55 the latent variable of protective resources included personal income, satisfaction with friends and family life, participation in social activities and self-esteem. This variable acted as a protective factor against mental health outcomes in adulthood following childhood adversity. In the paper by Giovanelli et al,Reference Giovanelli, Mondi, Reynolds and Ou56 the latent variable of protective resources included cognitive advantage, family support, school support, motivational advantage, school commitment, student expectations of college attendance and social adjustment. This variable acted as a protective factor against the impact on occupational prestige following childhood adversity.

Other protective factors

Curtis et alReference Curtis, Oshri, Bryant, Bermudez and Kogan57 found that socioeconomic instability mediated the relationship between childhood adversity and respect-based masculine ideology. Although socioeconomic instability confers a less favourable change in the outcome (i.e. decreased respect-based masculine ideology, as defined by the authors), it was judged that the measure, if inversely scored, would reflect socioeconomic stability. Therefore, this paper demonstrates that socioeconomic stability is associated with a minimised effect of childhood adversity on respect-based masculine ideology. Wickrama and NohReference Wickrama and Noh58 found that adolescent adjustment was a protective factor for educational attainment following childhood adversity.

Risk of bias in studies

Scores on the MASTER tool for each study are presented in Tables 3–6. The median score was 17, with an interquartile range of 2. There were many items that were irrelevant to the papers in our review, and so were scored as ‘unmet’; examples of such items are items 13–16, which relate to study blinding. All items that were not applicable to any paper in the review can be seen in the full list of safeguards and our interpretations in Supplementary Appendix 3. This process revealed that although the MASTER tool is adaptable to different study designs, there are many aspects that are not applicable to observational studies.

Table 6 Details of included studies examining relationship factors, multiple protective factors and factors that did not fit into other categories as mediators

MASTER, Methodological Standards for Epidemiological Research; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations; ACE, adverse childhood experience.

Quality of evidence

Scores on the GRADE for each domain are presented in Tables 3–6, and the full breakdown is supplied in Supplementary Appendix 4. The GRADE checklist was applied to the four domains containing more than one paper: social support, education, personality and dispositional factors, and romantic relationship factors. The two papers examining multiple protective factors were deemed too different to combine into one certainty assessment. All assessed domains were deemed to have very low quality of evidence on the GRADE checklist.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to identify, synthesise and critically appraise studies that have found protective factors for adult outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity. This is the first systematic review to examine protective factors following cumulative childhood adversity for any outcomes that are social, occupational, psychological or related to mental health and well-being. We found that social support, education, and personality and dispositional factors were clear domains of protective factors. Further research is needed to examine the protective role of romantic relationships and how multiple protective factors may act together to promote positive adaptation following cumulative childhood adversity.

The clearest pattern that emerged from the literature was that social support is a protective factor for mental health outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity. This finding is consistent with the wider literature detailing the protective role of social support for mental health, particularly in adolescence and young adulthood.Reference Stewart and Suldo59 This developmental period has been identified both as a time with increased importance of social connection, and as a sensitive period for the development of internalising disorders, particularly for those who have experienced adversity in childhood.Reference Rapee, Oar, Johnco, Forbes, Fardouly and Magson60 Therefore, during this sensitive period, the stable role of friends and family may protect against the development of internalising disorders. This finding suggests the opportunity for preventative programmes enhancing social support in adolescence. The evidence for social support as a protective factor in this review was deemed to be of very low quality, so we must interpret this with caution. However, this review supports the existing literature and suggests the need for further, high-quality research into social support's protective role for mental health outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity. It is interesting that we did not find social support to be a protective factor for other outcomes, although there is some evidence for this in cross-sectional papers.Reference Melkman61,Reference Vranceanu, Hobfoll and Johnson62 More longitudinal research is needed to test whether social support could also be an area for intervention for other outcomes in addition to mental health.

Education and academic factors also emerged as a domain of protective factors for mental health, socioeconomic and offending outcomes following cumulative childhood adversity, as well as general adversity. These findings are consistent with, and extend, extant literature describing the protective role of education for disadvantaged young people, and its role in minimising health inequalities.Reference Topitzes, Godes, Mersky, Ceglarek and Reynolds63,Reference Stavrou and Kourkoutas64 There are many potential avenues through which education could promote positive adaptation, and research in this area has turned to delineating the specific contributions that different aspects of education provide. For example, performing well at school and graduating may enhance self-esteem and self-efficacy, which are influential in pursuing higher education or challenging and prestigious jobs. There is also some research to suggest that the socioemotional adjustment to a classroom environment can have benefits f-or adult mental health, smoking and drug use.Reference Topitzes, Godes, Mersky, Ceglarek and Reynolds63 This is an area that has great potential for future research in elucidating some of these finer details and potential areas for intervention.

Another domain of protective factors that emerged in this review were personality and dispositional factors, which are well-established as important drivers of positive adaptation following childhood adversity. Personality is especially influential because there tends to be high similarity between adulthood and childhood personality,Reference Shiner, Masten and Tellegen65 so the effects seen in the included studies likely describe the differences in responses to adversity based on personality, rather than a protective effect necessarily. Personality itself is also likely shaped by childhood adversity, as it emerges from an interaction of temperamental factors with environmental effects. Therefore, although we selected for papers that measured protective factors specifically after childhood adversity exposure (and not during), these intrapersonal protective factors may describe personality processes interacting with exposures to childhood adversity during and after exposure. There is established literature detailing the roles of self-awareness, openness, optimism and self-mastery in children who have relatively good outcomes after experiencing traumatic situations.Reference Zhao, Han, Teopiz, McIntyre, Ma and Cao66,Reference Shiner and Masten67 Although this finding is informative as to which individuals may be more or less affected by adversity, it is less relevant in the pragmatic approach of pursuing amenable factors to inform wider social policy or community interventions.

Strengths and limitations

This review has provided a comprehensive summary of the current literature on protective factors following exposure to cumulative childhood adversity. The research on this topic is diverse and multidisciplinary, and it has required summary for some time. This review gives a backdrop for future positivistic research into strategies to reduce the long-term burden of childhood adversity.

Because of the multidisciplinary interest in this area, there was large heterogeneity in the description and measurement of childhood adversity and protective factors. This was found both in the studies included in the present study, and in the wider body of literature. This heterogeneity resulted in some key limitations. First, we could not perform meta-analysis, as this requires a reasonable degree of similarity (e.g. in how variables are measured). Despite this, it was important to perform a narrative synthesis of the area, and we found valuable groupings of protective factors following childhood adversity. These can be considered targets for future research and review. Second, the heterogeneity required care to be taken in designing eligibility criteria that was both necessarily and sufficiently inclusive. Criteria were chosen to balance reducing heterogeneity enough to generate meaningful findings while still being inclusive of a wide body of research. Even with narrower criteria, the large amount of heterogeneity confirms a need toward more unified research on long-term outcomes of childhood adversity.

The use of different measurement tools in this review has limited the ability to compare papers. This was the case for measures of childhood adversity, mediators and outcomes. All of the included studies were longitudinal cohort studies, many of which were measured from birth. These types of studies rely on measurement standards at the time of data collection. Therefore, it is difficult for these studies to have consistency in what they measure. In any case, it is clear that there is a need for established norms in choosing measures, so that comparison of effects may be possible in the future.

A final limitation of this review is that the quality of evidence for every category, as ascertained by the GRADE assessment, was very low. However, in the GRADE assessment, observational studies start on a ‘low’ score, and marking upward is rare. Further marks down were most prominently because of inconsistency, based on the inability to meta-analyse any of the groups. The findings of this review must therefore be taken in consideration of the very low quality of evidence. The quality assessment can be considered a finding in itself, and suggests that observational studies need to aim for a higher quality to achieve the same level of certainty as experimental research. GRADE criteria to improve certainty are a large magnitude of effect, a dose-response gradient and control for confounding.

Implications

It must be noted that none of the studies in this review demonstrate causative effects, and it is not possible to say that enhancing these factors would lead to reduced burden, or why these factors are associated with lower burden. However, these studies point to potential targets for developing interventive or preventative strategies. These can be applied to the contexts of clinical practice, policy change and future research.

In terms of clinical practice, there is a prevalent population who are experiencing mental health difficulties as a result of adversity in childhood. This review supports interventions for this population that target enhancing social support systems, as well as ‘resilient’ traits such as self-esteem, mastery, optimism or self-regulation.

For policy, this review demonstrates that investment in education may be an important tool to reduce disparities for children who have experienced adversity. Although education is widely known to reduce disparities for disadvantaged children, it may also reduce many unseen disparities for children with high levels of adversity exposure who may not be classed as ‘disadvantaged’.

Finally, this review suggests that much future research is needed to address the limitations in the area of protective factors following adversity. This research should focus on a unified approach, and calls for this are not new.Reference Walsh, Dawson and Mattingly68,Reference Kaufman, Cook, Arny, Jones and Pittinsky69 This could be achieved through use of inclusive measurement of exposures to childhood adversity, and childhood adversity scores that include all possible exposures. Additionally, a more unified approach would result from a multidisciplinary forum, recognising that this is a topic of importance to many disciplines.

In conclusion, the experience of adversity in childhood is a significant risk factor for poor adult psychosocial outcomes, and heightened exposure to adversity enhances the likelihood and breadth of these outcomes. However, increasingly, research demonstrates that cumulative childhood adversity does not deterministically lead to an adverse adulthood. This review provides an overview of the current literature on protective factors following cumulative childhood adversity exposure. The findings suggest that increased social connection may be related to improvements in adult mental health outcomes, education has wide-reaching benefits and supporting resilient personality traits early appears to have long-term positive effects. These are all important areas to consider in further research, and provide clear and feasible targets for researchers and policy makers to consider. This review highlights the importance of a more unified approach to support future analytic review.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.561

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable as no new data were created in this review.

Author contributions

M.B., J.M.B. and G.N.-H. designed the review protocol and search strategies. M.B. and G.W. performed the abstract and full-text screening, and conducted risk-of-bias and quality of evidence assessments, with the advice of author G.N.-H. M.B. and Z.M. performed the abstract and full-text screening for the second ‘catch-up’ screen. M.B., Z.M. and G.N.-H. performed the data extraction. M.B. was the main author of the paper and wrote most of the text, with significant input from authors G.W., J.M.B., Z.M. and G.N.-H.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.