I doubt whether tomorrow a constitutional court will appear in every unit of the Federation. It seems to me that this will not happen. (Valery Zorkin, Russian Constitutional Court Chairman, November 26, 2003)

Introduction

A growing number of theories of post-Communist judicial empowerment link the democratic transition to the establishment of constitutional review. According to them, political elites create powerful, independent constitutional courts to enforce post-communist constitutions in the context of enormous sociopolitical uncertainty. “New institutionalists” Lane and Ersson conclude using cross-national statistical analysis that “if a country wishes to introduce democracy, then the best institutional devices it could employ in constitutional engineering are legal institutions such as strong legal [judicial or constitutional] review” (2000:178). This analysis stresses the importance of international pressures and templates in the process of massive constitutional (non)borrowing from the West (Reference DupreDupre 2003; Reference OsiatynskiOsiatynski 2003; Reference ProchazkaProchazka 2002; Reference SchwartzSchwartz 2000). Subjecting their policy choices to judicial review, post-Communist rulers demonstrate their commitment to democracy and the rule of law to their domestic constituencies and to the rest of the world. Constitutional courts, then, uphold democratic values, protect individual rights, and serve as a bulwark against the return to the totalitarian past.

Interest-based approaches to post-authoritarian judicial empowerment in societies as diverse as Japan and Bulgaria focus on domestic variables, such as the structure of political party systems (Reference RamseyerRamseyer 1994; Reference MagalhãesMagalhães 1999). Reference GinsburgThomas Ginsburg (2003) compares the politics of creating constitutional courts in Taiwan, Korea, and Mongolia and argues that, in the uncertainty of democratization, politicians who fear electoral loss create a strong and independent judiciary to protect themselves from the tyranny of election-winners in the future. Weak political parties or several deadlocked ones are likely to produce powerful, independent, and accessible judicial review. Strong dominant political actors are likely to design limited judicial review with restricted access. Similarly, by drawing on the 220-year history of state supreme courts in the United States, Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight (2003) theorize that when political uncertainty is high, constitution makers are less likely to constrain judicial review bodies. Constitutional courts, then, protect political minorities by providing them with a forum to obstruct majoritarian decisionmaking.

My analysis examines only the first part of this hypothesis, namely the interplay of ideas, interests, and institutions in the processes of creating powerful (at least on paper) courts in Russian regions. Of the eighty-nine regions, fifty-six established courts in their constitutions/charters, twenty passed court statutes, and seventeen of those created courts in reality, two of which failed (see Map 1 and Table 1). Eight of them began their work before 1996 (see Table 2), i.e., earlier than many of the post-Soviet constitutional courts (Reference MitiukovMitiukov 1999:5). Between 1992 and April 2004, Russia's regional constitutional courts issued 350 decisions on the merits of the case (the Russian Constitutional Court issued 211 decisions during the same period), having struck down equal proportions of executive and legislative acts in 60% of the cases, which included numerous politically charged disputes between regional legislatures and governors over fiscal policies, electoral procedures, and socioeconomic rights (Reference TrochevTrochev 2001a). Their main job is determining whether regional and local laws and decrees comply with the regional constitutions (charters) through a posteriori abstract and concrete constitutional review procedures (Reference TrochevTrochev 2001b).

Map 1. The Geography of Russian Regional Constitutional Courts

Table 1. Features of Russia's Regions With Functioning Constitutional/Charter Courts

* The lower the number in this column, the better the quality of life in the region. Arrows indicate whether the region moved up or down in Human Development Index ratings from 1998 to 1999. Dashes indicate no change in ranking.

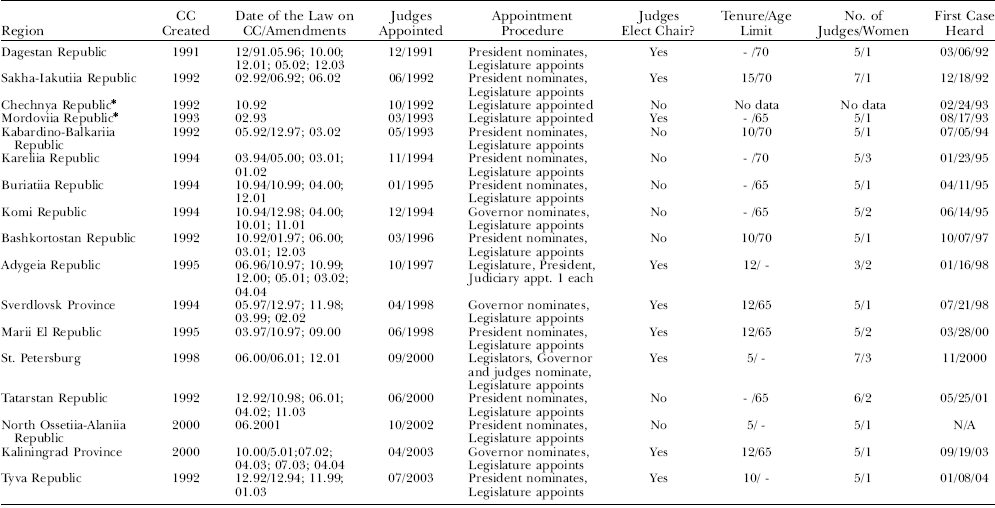

Table 2. Russia's Regional Constitutional/Charter Courts (CC) in Chronological Order

* Failed courts.

I focus on the puzzles: why only some regions created their own constitutional courts, why some delayed making their courts operational, and why others moved to dissolve them. Mainstream theories predict that accessible constitutional courts will be established in those regions where ruling elites exhibit their commitment to democratic principles or where political party systems are competitive and/or fragmented. To check the explanatory power of these theories, I provide data on the length of incumbency and electoral successes of the most powerful regional politicians before and after the creation of these courts (Table 3). This serves as a proxy for measuring their estimates of electoral uncertainty. Most of these courts were created in those regions where governors consolidated their power so well that they feared losing elections neither during the courts' creation nor a decade after that. This is because governors “were surprisingly agile in their dealings with Moscow, adept at retaining control over resources and gaining new prizes, and largely successful at remaining in power” (Reference McAuleyMcAuley 1997:312). Only very powerful governors could resist federal attempts to concentrate power at the federal level, including the judicial system. These governors amassed sufficient power to both control federal courts located in their regions and afford their own constitutional court. This means that politicians set up judicial review both to consolidate and to retain their power vis-à-vis central and local governments, contrary to judicial empowerment theories. Russia's subnational political elites did not simply follow the prescriptions of the federalist rationale for creating one federal judicial body to review federal-regional disputes. Instead, subnational constitution makers decided to have their own courts to police Russian federalism.

Table 3. Creation of the Constitutional Courts and Electoral Certainty (in chronological order)

* Election by a special Constitutional Assembly.

** Based on the Freedom House democracy ranking methodology, each score is an average of the sum of ten indicators (separation of powers, openness of political process, role of elections, political pluralism, freedom of press, corruption, civic activism, economic liberalization, elite turnover, and local self-government), constructed by the Moscow Carnegie Center (Reference PetrovPetrov 2002).

*** Measured by electoral turnout, electoral competitiveness, protest vote, and electoral violations at regional and federal elections.

**** Failed courts.

Note: Entries in bold indicate an uncontested election.

Indeed, as Reference HirschlHirschl (2000, Reference Hirschl2004) argues, strong judicial review “may provide an efficient institutional way for hegemonic sociopolitical forces to preserve their hegemony and to secure their policy preferences” (2000:75) because dominant political elites can influence judicial decisionmaking via judicial recruitment and ideological propensities (Reference TsebelisTsebelis 2002; Reference Russell and SolomonRussell 2004). Although Hirschl tests his explanation of successful judicial empowerment in five culturally divided polities (Israel, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and Egypt), my analysis is not limited to the Russian regions that have salient ethnic or religious cleavages. Nor do I focus only on the successful cases of judicial empowerment. Thus I have more observations to test my argument that dominant political elites set up constitutional courts to entrench their ruling status vis-à-vis other political forces (federal government, local mayors, religious or ethnic minorities).

Following the approaches to study subnational constitution-making in eighteenth-century United States (Reference LutzLutz 1980) and democratic transitions around the world in the twentieth century (Reference HuntingtonHuntington 1991), I use “waves” to examine the interaction of federal and regional elites in the process of regional constitution-making that led or failed to lead to a particular model of constitutional review. Each wave of regional court-building is a group of processes that results in the establishment of constitutional courts within a specified period of time and that significantly outnumbers the processes of the court dissolution during that period of time. A wave usually involves the establishment of the court in the constitution or charter of the region, the passage of the court statute, and appointment of the justices. This wave may be followed by a reverse wave when politicians dissolve judicial review or make it inoperative, as is the case after the first wave. Although any categorization of Russian regional constitution-making is arbitrary, I propose the following periodization:

| First wave of regional court-building | April 1990–October 1993 |

| First reverse wave | June 1993–February 1994 |

| Second wave of regional court-building | April 1994–January 1997 |

| Third wave of regional court-building | January 1997– |

The first wave began when several regions of Russia emulated the USSR Constitutional Supervision Committee by setting up their own quasi-judicial review bodies with advisory powers. In 1991–1993, eight Russian republics followed the federal constitutional court template and entrenched constitutional courts in their constitutions. In Dagestan, Sakha, Chechnya, and Mordoviia these courts quickly began their work. The first reverse wave began with the dissolution of the Chechen Constitutional Court by President Dudaev, whose decrees the Court frequently struck down. The suspension of the Russian Constitutional Court strengthened this reverse wave, and in February 1994 the Mordoviia Parliament dissolved its constitutional court via constitutional amendment after the justices publicly criticized regional lawmakers.

The second wave began in spring 1994 with the passage of the Kareliia Constitutional Court Act. This wave involved active court-building initiatives in various regions and continued to include quasi-judicial constitutional supervision committees. Three more regional courts (Kareliia, Komi, and Buriatia) began their work and received their encouragement from the reconstituted federal Constitutional Court. I argue that during the first two constitution-making “waves,” Russia's regional constitutional courts were created by well-entrenched political and legal elites to enhance the political standing of their regions versus the federal government. In this period, regional rulers set up their own courts only when they had no overt challenges to their power.

The 1996 federal law on the judicial system legitimized regional constitutional courts and paved the way for the current third wave. At this time, nine regions formed their own judicial review bodies. During this “wave,” federal and regional politicians also learned to use regional constitutional review to legitimize policies and consolidate their power in their struggles against each other and local governments. They opted for their own courts to compensate for the loss of control over ordinary courts. Finally, I examine how and why current Russian judicial reform both legitimizes and limits the jurisdiction of regional constitutional courts, and I conclude by introducing yet another puzzle of judicial review, Russian-style. I start by making the case for comparative research on subnational institution-building followed by the outline of the basic structure of Russian federalism.

Why Subnational Courts?

Learning why post-Communist courts are created is important for an understanding of domestic support for post-Communist constitutionalism. The analysis of judicial institution-building at the subnational level provides fertile ground for research into domestic conditions favoring or discouraging the growth of “rule of law” institutions. The emphasis on domestic factors is important because subnational actors are not primarily concerned with joining international agreements and organizations. Subnational governments are members of the federation by default. They do not risk being expelled from the federation for rigging elections and disregarding human rights. Although subnational units have to follow federal standards in many policy areas to receive federal funds, the federal government does not fund the establishment of regional courts. Nor could subnational political elites receive funding for these courts from abroad. This means that domestic politics determine the institutionalization of subnational judicial review, yet we know very little about the establishment and work of subnational constitutional courts.

However, national-level comparative studies of constitutional court–building must account for the influence of international pressures and opportunities, resulting in a certain institutional arrangement (Reference ProchazkaProchazka 2002; Reference SadurskiSadurski 2002; Reference SchwartzSchwartz 2000). For example, the international community demands that former Yugoslav republics liberalize their economies, hold free elections, and protect human rights before receiving financial aid and joining the Council of Europe, NATO, and the EU. All post-Communist countries routinely send their draft legislation for approval to international organizations. Thus, studying the politics of the creation of national-level constitutional courts would give us an incomplete picture of post-Soviet constitutionalism because we would only witness the power struggles of central elites and the demands imposed by international funding agencies. We would miss the local responses to massive constitutional “gardening” (Reference LudwikowskiLudwikowski 1998) and would fail to trace the patterns of the indigenous grassroots demand for judicial review and constitutionalism in general (Reference Gray, Hendley, Sachs and PistorGray & Hendley 1997; Reference HendleyHendley 1999). In short, I focus on subnational court-building to isolate international influences and to examine how domestic political competition leads to judicial empowerment.

The Russian Federation: Background

The Russian Federation is unique in terms of the complexity of its structure and multi-ethnic composition due to Soviet and Tsarist legacies (Reference OvsepianOvsepian 2001:12–13). The eighty-nine units, or “subjects of the Federation,” vary in their constitutional status: thirty-two of them (twenty-one republics, ten autonomous districts, and one autonomous province) are ethnically defined, while the remaining forty-nine provinces, six territories, and the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg are almost entirely populated by ethnic Russians. Although all regions possess equal constitutional rights, republics have the most power, while nine autonomous districts are also included in the composition of six provinces and one territory (so-called matryoshka federalism). Under the 1993 Russian Constitution, republics are defined as states (Article 5.2), and they are free to choose the way to adopt their own constitutions, while the rest of the regions have to adopt their charters exclusively by their legislatures (Article 66). Article 68.2 of the federal constitution grants republics the right to establish an official “state language.” More important, republics actively use their capacity to legislate, inherited from the Soviet era, and pioneered the practice of signing bilateral treaties with the federal government, which increased asymmetry among regions in the 1990s. Republics were also the first to set up their own courts: fourteen of them in the past decade, compared to only three in the rest of the regions.

In the late 1980s to early 1990s, these republics were at the front of the “sovereignty parade,” a spontaneous process of entrenching their autonomy from both the USSR and the Russian Federation (see Reference KahnKahn 2002). The USSR was formally organized as a federation of fifteen “Union Republics,” with Russia, itself a federation, being one of them. While the USSR leadership strongly opposed the “sovereignty parades” by Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia that threatened the legitimacy of the Soviet Union as a socialist federation, USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev actively encouraged similar efforts by the republics within Russia in order to weaken the Russian Federation's push for greater autonomy. Gorbachev promised republican elites that he would upgrade the status of their republics and allow them to sign the Union Treaty as equal members of the new Union (Reference Dunlop, Bremmer and TarasDunlop 1997:34). At this time, Russia had neither the institutional resources nor the political will to oppose these “status-upgrading” strategies of its constituent parts (see Reference Fondahl, Bremmer and TarasFondahl 1997; Reference Frank, Wixman, Bremmer and TarasFrank & Wixman 1997; Reference KahnKahn 2002; Reference Lapidus, Edward and LapidusLapidus & Walker 1995; Reference Mandelstam, Marjorie, Millar and WolchikMandelstam Balzer 1994; Reference Ormrod, Bremmer and TarasOrmrod 1997). Moreover, in its struggle with the Soviet Union, Russia was eager to gain the support of its regions and encouraged these “sovereignty parades” as long as they did not secede from Russian jurisdiction (Reference KahnKahn 2002; Reference Dunlop, Bremmer and TarasDunlop 1997:36). Republics passed their declarations of sovereignty and ratified their constitutions, enshrining their own statehood, citizenship, control over natural resources, and even war-making powers. However, the Russian Constitutional CourtFootnote 1 repeatedly struck down all attempts by the republics to constitutionalize their “sovereign” status and championed the constitutional symmetry of the Russian Federation (Reference Trochev, Solomon, Reddaway and OrttungTrochev & Solomon, forthcoming).

The First Wave: Constitutional Courts—for Republics Only

The first wave began in the spring of 1990 with the creation of constitutional supervision committees (CSC)Footnote 2 in several republics and lasted until the suspension of the Russian Constitutional Court in fall 1993. Only eleven republics established some kind of constitutional review body during this wave. Why did Russia's republics create their own constitutional courts faster and before the rest of the Russian regions? One clue may be in their “higher” autonomous status relative to the other units of the Russian Federation. They had the authority to pass their own laws, while other Russian regions did not. The republican lawmaking boom in the early 1990s also meant a constant supply of work for the constitutional review bodies to check the quality of these laws and protect their constitutions and their newly gained “statehood” from encroachment by Soviet or Russian authorities.

The establishment of federal constitutional review strongly influenced the creation of regional bodies. At the federal level, work began with the establishment of the USSR Constitutional Supervision Committee in 1989. Soon thereafter in 1990, several republics (Komi, North Ossetiya, and Tatarstan) created their own CSCs to determine the constitutionality of regional laws and decrees, acts of governmental bodies and public associations, and so on. All three CSCs began their operation in December 1990 against the background of the struggle between autonomy-minded Russian political elites and USSR authorities. In 1990–1991, the Russian legislature established the posts of President and Constitutional Court in an attempt to secure its territorial integrity and “sovereign status” within the USSR.

For example, in Komi Republic, located in the northwest Ural mountains and endowed with rich natural resources, Yuri Gavriusov, the CSC chairman, told the Komi legislature that he imitated the USSR Committee rather than the full-blown Constitutional Court to design the Komi CSC (Verkhovnyi Sovet Komi ASSR 1990a:189). Komi legislators expected that this Committee would produce prompt quality control of Komi regional laws by checking their compliance with the Komi Constitution (Verkhovnyi Sovet Komi ASSR 1990a:204, 286). Still, the Komi Parliament debated the creation of a constitutional review for two months and failed to authorize the CSC budget at once. As Speaker Yuri Spiridonov put it, the Komi CSC Act was adopted, although the legislators, who simply did not want any oversight of their lawmaking boom, distrusted it (Verkhovnyi Sovet Komi ASSR 1990b:274).Footnote 3 Nor did he, the most powerful Komi politician at that time, fully control the legislature in fall 1990. As a result of extensive political compromise in the context of the collapsing USSR, the Komi CSC rulings were not final and could be overridden by the legislature. Current judicial empowerment theories suggest that the uncertainty of the transition, political competition, and the absence of a dominant political force were conducive to the creation of constitutional courts. However, in Komi in 1990, political elites chose to model their constitutional review after the USSR CSC to ensure their ruling status and their control over new institutions. As I will discuss below, counter to the theoretical predictions, Spiridonov, the soon-to-be Komi governor, allowed the creation of a powerful and accessible constitutional court as he successfully consolidated his power in the region.

Once the Russian Parliament made it clear that it would create a real constitutional court in 1991, several Russian republics chose to set up constitutional courts on this model. These courts were empowered to protect the constitutional foundations of these republics, to determine the constitutionality of federal laws and of the treaties between the republics and Moscow. Their creators saw these courts as a first step toward a modern, sovereign, law-based state with separation of powers and its own judicial system, just as in the United States, where states have their own judicial systems, and Germany, where Länder have their own constitutional courts (Reference Gavriusov, Kataev and SamigullinGavriusov 1992:63; Reference Oorzhak, Kataev and SamigullinOorzhak 1992:118; Reference Dolgasheva, Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiDolgasheva 2000:121).

The first subnational constitutional court in Russia was established in Dagestan Republic, a small poverty-stricken region of the north Caucasus populated by eleven ethnic groups (Table 1). The Dagestan Constitutional Court was elected in December 1991 and issued its first decision on March 6, 1992, invalidating markups on the prices of alcohol (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:285). Although a diverse, multi-ethnic composition of the republic could contribute to the introduction of the judicial review resolving inter-ethnic disputes, successful power consolidation strategies by Dagestan's leading politician, then-Chairman of the Legislature Magomedali Magomedov played a more important role in this process. Magomedov, a former Communist Party boss, has been in power since August 1987. In 1990, his election to head the republic was uncontested, and again in 1994, 1998, and 2002. Currently Dagestan president, Magomedov is widely expected to win upcoming elections in 2006 and to keep his post until 2010 (Reference AkopovAkopov 2002).

The second subnational constitutional court was introduced in the heartland of Siberia—Sakha-Iakutiia, the largest republic within the Russian Federation. The February 1992 Sakha Constitution established a constitutional court, and justices were elected in June 1992, issuing their first decision on December 18, 1992, requiring municipalities to honor their contracts with individuals (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:609). The court was established after Sakha President Mikhail Nikolaev was firmly entrenched in power. Before winning the presidency with 77% of the popular vote in December 1991, Nikolaev chaired the legislature for two years. In fall 1991, he refused to supply the federal treasury with gold and diamonds and withheld federal tax revenues. Nikolaev was re-elected in 1996 and was stopped from running for the third term in December 2001 only by active efforts of the federal government.

In 1992–1993, several other republics (Bashkortostan, Chechnya, Kabardino-Balkariia, Mordoviia, Tatarstan, and Tyva) adopted their constitutions and established constitutional courts, but were slow to elect the justices. Thus, the Kabardino-Balkariia Constitutional Court began its work in July 1994, well after the head of the republic's legislature, Valerii Kokov, won presidential elections in 1992 with 89% of the vote (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:333). President Kokov repeated his success in the 1997 uncontested election, winning 93% of the vote, and, if re-elected, he can keep his post until 2012 (Reference AkopovAkopov 2002). Around the same time, individuals received the right to challenge any republican law in the Kabardino-Balkariia Constitutional Court, contrary to the judicial empowerment thesis that power consolidation leads to a restricted version of judicial review.

The Bashkortostan Constitutional Court made its debut in October 1997, five years after its entrenchment in the 1992 Bashkortostan constitution, by asserting the authority of the republic to pass civil legislation (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:221). This court began its operation when the power of Bashkortostan President Murtaza Rakhimov was at its highest. Rakhimov has ruled since 1990 and won the presidency in 1993 and 1998 with 64 and 70%, respectively. The Constitutional Court of the Tatarstan republic, founded in November 1992, began its operation in June 2000 when Tatarstan President Mintimer Shaimiev was so entrenched in his position that even Putin's administration could not prevent him from running for and winning a third term in March 2001. Both the Bashkortostan and Tatarstan presidents have the opportunity, if re-elected, to rule for another decade (Reference AkopovAkopov 2002). Finally, justices to the Tyva Republic's constitutional court, founded in December 1992, were appointed only in July 2003! Tyva President Sherig-ool Oorzhak has been in power since April 1992, when he won the election with 83% of the vote. Oorzhak repeated his success twice in 1997 (71% of the vote) and 2002, and has excellent prospects of being re-elected in 2007 for another five-year term (Reference KahnKahn 2002:211). To sum up, Russia's regional political elites set up constitutional courts in their republics only after they consolidated political power. As will be shown in “The Third Wave,” presidents of autonomy-minded regions agreed to make their courts operational either to consolidate the executive power or to compensate for their loss of control over the federal judiciary.

Like the Russian Constitutional Court, many of the regional constitutional courts faced problems in their early years. Moreover, this first “wave” of court formation was followed by a reverse wave, a dissolution of constitutional courts. It began in June 1993, when Chechnya President Dzhokhar Dudaev disbanded the republican constitutional court after it repeatedly ruled against him and threatened to impeach him in May 1993 (Reference MuzayevMuzayev 1993; Reference PacheginaPachegina 1993). The Chechnya legislature created this court in October 1992 and elected its chief justice in a fierce competition among nine candidates for the bench. Dudaev did away with the court during a severe clash with the legislature, which he suspended in June 1993. This was prior to the rise of his popularity, which skyrocketed in mid-1994 on a wave of anti-Russian sentiment (Reference Ormrod, Bremmer and TarasOrmrod 1997:103–07). In mid-1993 Chechnya, we observe that vibrant political competition with no dominant political force led to the failure of judicial review, contrary to what judicial empowerment theories would predict.

In the Mordoviia republic, the legislature created the court in April 1993 and quickly appointed its members. Prior to the establishment of the court, eight candidates ran in the 1991 Mordoviia presidential race, electing the only non-Communist non-incumbent in the race. Again, judicial empowerment theories would predict the success of judicial review in the context of high electoral competition. The chairman of the Mordoviia legislature, Reference BiriukovNikolai Biriukov explained that a constitutional court was needed to uphold the republican constitution and to settle disputes between the legislature and the Mordoviia president, who followed Russian President Boris Yeltsin's strategy of undermining and ignoring parliamentary decisionmaking (1992:22). Legislators then skillfully used this court to abolish the position of the Mordoviia president and vice-president in 1993 (Reference TrofimovaTrofimova 1993). Mordoviia Constitutional Court Chairman Reference EremkinPavel Eremkin admitted that his court was created very quickly to resolve serious political conflict between the legislature and the executive (1994). He insisted that a constitutional court represented a civilized way of settling constitutional controversies in a democratic state. Although Eremkin did not believe that his court would be abolished, the legislature did away with it in February 1994, after judges publicly criticized the law makers (Reference VolkovVolkov 1994). Mordoviia political elites emulated Yeltsin's solution, which suspended the activity of the Russian Constitutional Court in October 1993 in his fight against the Russian legislature (Reference SharletSharlet 1993). Again, in the context of electoral uncertainty and severe political contestation, politicians chose to end judicial review contrary to the predictions of judicial empowerment theories.

Comparing the failures of these and other post-authoritarian courts to avoid involvement in political conflicts between branches of government may shift our attention from personalities—presidents, legislators, and chief justices—to the power-maximizing strategies pursued by these actors under certain institutional arrangements: flexible constitutions, easy access to the court, the many non-adjudicative powers of the court, and a low degree of judicial discretion. Or, as Reference Przeworski and TeunePrzeworski and Teune (1970) have argued, such comparisons would replace place-names with variables.

Federal Response

In the early 1990s, federal officials were largely indifferent to these court-building and court-dissolving strategies in the republics. In early 1992, the members of several republican constitutional review bodies asked the Russian Parliament to confirm their legitimacy and to approve the idea of their federal financing. They succeeded in getting the approval of the creation of regional constitutional courts as a legitimate exercise in line with Russian judicial reform and the 1992 Federation Treaty, which placed subnational constitutional review in the exclusive jurisdiction of the regions. Therefore, Moscow rejected federal financing of these courts because they were not part of the federal judiciary and, thus, only the regions themselves could finance them (Reference BobrovaBobrova 2000:62).

Although the Constitutional Convention that Yeltsin convened in summer 1993 attempted to equalize the status of all units of the federation, federal officials informally gave assurances that republics would have their own courts (Reference Gavriusov, Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiGavriusov 2000:87). Many representatives of the republics wanted to include norms about regional courts in the federal constitution. Federal representatives argued that it was up to each republic to decide whether to have its own constitutional court and opposed authorizing republican constitutional justice by the federal constitution since it would elevate the republics over other regions (Reference Mitiukov and BarnashovMitiukov & Barnashov 1999:281).

The Russian Constitutional Court justices actively supported the introduction of the constitutional courts in all regions to protect constitutional foundations and individual rights, to strengthen the legitimacy of constitutional review, and to lighten the workload of the federal constitutional court (Reference Vedernikov, Ershov, Radutnaia and VedernikovaVedernikov 2000:163; Reference Gadzhiev and KriazhkovGadzhiev & Kriazhkov 1993). However, they rejected the subordination of the regional constitutional judiciary to the Russian Constitutional Court (Reference Gadzhiev and KriazhkovGadzhiev & Kriazhkov 1993:9; Reference VedernikovVedernikov 1998:70).

In short, the first wave (April 1990–October 1993) of the regional constitutional court formation arose entirely due to the initiative of the political and legal elites in the republics and involved both judicial and quasi-judicial bodies of constitutional review. Under the 1992 Federation Treaty, Russia's republics received state-like characteristics with broad lawmaking and institution-building powers. Heads of the republics managed to gain serious concessions from the federal government and used them very skillfully to consolidate their power. They created republican constitutional courts as a first step toward subnational judicial systems, separate from the federal judiciary, only after they solidified their power. Political elites in those republics with highly contested elections and legislative-executive conflicts quickly did away with judicial review. Therefore, the evidence from eleven Russian regions refutes the thesis that political uncertainty and power diffusion lead to the creation of strong judicial review.

The Second Wave: Provinces Want to Have Their Own Constitutional Courts, Too

The second “wave” of subnational constitutional court-building (April 1994–January 1997) was directly connected with the revival of the federal Constitutional Court after its suspension in fall 1993. The December 1993 Russian Constitution (Article 125) kept the Russian Constitutional Court as an independent and powerful judicial body. At the same time as the Russian Parliament debated the draft Russian Constitutional Court statute in spring 1994, Kareliia Republic, located in northwest Russia on the Finnish border, created its own constitutional court in March 1994 (Zakon RK “O Konstitutsionnom Sude Respubliki Kareliia” 1994). Following the adoption of the 1994 Russian Constitutional Court Act (Federalnyi konstitutsionnyi zakon “O Konstitutsionnom Sude RF” 1994) in July 1994, other republics either adopted laws creating their own constitutional courts (Adygeia, Buriatiia, and Komi) or amended their existing laws (Dagestan, Tuva). This wave included federal recognition of subnational courts beyond republics and lasted throughout 1996, until the federal constitutional law “On the Judicial System of the Russian Federation” entered into force in January 1997 (Federalnyi konstitutsionnyi zakon “O sudebnoi sisteme RF” 1997).

Although this wave began with the creation of the Kareliia Constitutional Court in March 1994, the justices to this court were appointed only in mid-November of that year, seven months after the incumbent Kareliia governor, Viktor Stepanov, won uncontested gubernatorial elections. The Kareliia Constitutional Court is very accessible. In addition to individuals, any legislator, nongovernmental organization, and business entity could initiate judicial review procedure. Again, the lack of political competition and power consolidation by the executive seems to go hand in hand with the formation of judicial review.

In Komi Republic, the members of the CSC drafted the bill on the constitutional court. They simply copied the 1994 Russian Constitutional Court Act and argued for the establishment of the judicial branch of the government as a necessary element of constitutional reform (Verkhovnyi Sovet Respubliki Komi 1994a:141). Two months after the Komi Constitutional Court Act was quickly passed in October 1994,Footnote 4 the parliament quietly appointed four gubernatorial nominees to the bench.Footnote 5 When asked by a university student why the Komi people needed a constitutional court, Governor Spiridonov (not an active supporter of the court), who ruled in 1990–2001, compared the court to the accountant who is necessary to hold the boss accountable.Footnote 6 Again, the well-entrenched executive seemed to go hand in hand with the prompt establishment and appointment of accessible and powerful (at least in theory) judicial review. Moreover, as the power of the governor grew, access to the court was also extended in 1998 to a group of five legislators.

The same pattern of power consolidation leading to the creation of the constitutional court was evident in Buriatiia, a republic in southern Siberia on the Mongolian border. Buriatiia President Leonid Potapov was well-entrenched in power since 1990, first as a Communist Party boss and then as speaker of the legislature. As shown in Table 3, he always wins elections and can serve until 2010 if re-elected (Reference AkopovAkopov 2002). The Buriatiia Constitutional Court was set up in October 1994 and began operating in January 1995. Furthermore, this court became more accessible as the power of the president grew: the right to petition the court was granted to each member of Parliament in 2000, contrary to judicial empowerment theory.

This group of republican constitutional courts was set up very quickly: there were no long parliamentary debates or executive vetoing of the laws on the constitutional courts, the justices were appointed quickly, and all nominees received their seats on the bench. This swiftness in court-building processes again shows the domination of lawmaking by powerful executives in these republics. Moreover, the stronger the dominant political actors became, the more accessible the judicial review that ensued.

The second wave of subnational court-building spread beyond the republics and brought about constitutional courts in provinces, territories, and districts, where they were called “charter courts.” The call for the creation of constitutional courts in these regions was already voiced at the 1993 Constitutional Conference in Moscow (Reference Mitiukov and BarnashovMitiukov & Barnashov 1999:281). Again, here “the pioneer” was Sverdlovsk Province, which wanted to become the “Ural Republic” in order to elevate itself above other regions and to have its own constitutional court (Reference OchinianOchinian 1994). Then-Province Governor Aleksei Strakhov, an appointee of President Yeltsin, opposed the idea of having this court, arguing that it was an attribute of independent statehood incompatible with the Russian Constitution (Reference Smirnov and PerechnevaSmirnov & Perechneva 1994). Eventually, the 1994 Charter of Sverdlovsk Province (Ustav Sverdlovskoi Oblasti 1995) established the Charter Court, and the 1996 bilateral treaty with the federal government recognized the court (Reference RossiiskaiaRossiiskaia Gazeta 1996). Eduard Rossel', the then head of the provincial legislature and currently the provincial governor, spearheaded the idea of a provincial constitutional court as a symbol of true federalism and a guardian of the provincial Charter (Reference Rossel'Rossel' 2001).Footnote 7

Federal Reaction

In 1994–1996, the federal government produced contradictory policies toward this growth of regional constitutional justice. While the Russian Constitutional Court (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1995) and the 3rd All-Russian Congress of Judges (1994) supported it, the presidential administration considered the establishment of these courts illegal (Reference RossiiskieRossiiskie Vesti 1995). Lacking solid federal guarantees of their power and independence, the members of regional constitutional courts felt very vulnerable and dependent on the regional authorities. Fresh memories of the judicial review failures in Chechnya, Mordoviia, and Moscow made the threats to abolish courts in Dagestan and Kabardino-Balkariia very real (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1995:44). Regional constitutional court judges used every opportunity at the federal level to push for a federal requirement for these courts in every Russian region. They argued that their courts promoted constitutional order in the regions by enforcing the Russian Constitution. Their opponents countered that such courts multiplied contradictions between regional constitutions/charters and the Russian Constitution, undermined the integrity of Russian statehood, destabilized the Russian judicial system, and infringed upon individual rights because their rulings could not be appealed (Reference Davudov and ShapievaDavudov & Shapieva 1997:34; Reference ReshetnikovaReshetnikova 1996:4). The members of the then-existing Tatarstan and North-Ossetiia quasi-judicial constitutional supervision committees also complained about the forceful installation of these courts (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1995:36, 38).

The practice of signing bilateral treaties between the federal government and Russian regions (Reference KahnKahn 2002:Ch.6) displayed an inconsistent federal attitude toward subnational constitutional justice. Before the Russian presidential elections in 1996, several regions signed bilateral treaties with the federal government that authorized them to set up their own charter courts. The purpose of these treaties was to achieve a greater degree of regional autonomy from the center in exchange for votes supporting the incumbent president, Yeltsin. Note that the clauses on the charter courts appeared in the bilateral treaties with only those provinces that had a matryoshka structure (Reference WilsonWilson 2001), i.e., one that included other subnational units, autonomous districts, in their territory. While the bilateral treaty with Perm Province and Komi-Permiak Autonomous District mentioned the possibility of establishing charter courts in both the province and the district, the bilateral treaty with Irkutsk Province and Ust'-Ordyn Buriat Autonomous District mentioned the creation of a single province charter court (Reference RossiiskieRossiiskie Vesti 1996a, Reference Rossiiskie1996b). Thus, until January 1997, no consistent federal policies and laws regulated the activity of regional constitutional/charter courts. The federal response was split by the growing tension between the contribution of these new courts to the “sovereignty parades” and their role in equalizing the status of all Russian regions and protecting federal constitutional norms.

To sum up, this second wave of regional judicial institution-building was still characterized by the initiative of the regions. In addition to those of six republics, the charters of six provinces and three territories set up or mentioned the possibility of a constitutional/charter court or quasi-judicial chamber based upon the constitutional supervision committee model. Yet only Kareliia, Komi, and Buriatiia republics made their constitutional courts operational (Table 2). Why did regions fail to exploit contradictory federal policies and set up constitutional courts on a broader scale? The main reason was that by 1997, powerful regional governors had already established amicable relationships with the federal judiciary in their regions. Low levels of federal funding made federal judges dependent for their housing, perks, and benefits on regional authorities (Reference Solomon and FoglesongSolomon & Foglesong 2000). Several regions even attempted to have the judicial review free of charge by “empowering” federal courts to uphold the supremacy of their constitutions/charters (Reference Mitiukov and BarnashovMitiukov & Barnashov 1999:283). Moreover, creating a regional constitutional court would burden regional budget and generate criticism from the presidential administration (Reference UlitskiiUlitskii 1997).

The Third Wave: When Are You Going to Have Your Own Constitutional Court?

Finally, the current wave of regional constitutional justice building began in January 1997, when the 1996 Law on the Judicial System of the Russian Federation (hereinafter the 1996 Law) entered into force (Federalnyi konstitutsionnyi zakon “O sudebnoi sisteme RF” 1996).Footnote 8 The Russian Constitutional Court succeeded in including in the law norms regarding its regional “clones,” which constituted the first recognition of these courts by the federal government (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:86). According to the 1996 Law, regional constitutional courts are to be financed from the regional budgets, and their decisions are final and binding, not subject to review by any other court. Regional constitutional courts are not subordinated to the federal Constitutional Court, and they cannot be abolished without the simultaneous transfer of their jurisdiction to another court (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:31). Article 27 of this law allows the creation of constitutional/charter courts in the regions to determine whether regional laws, decrees, and acts of local government comply with the regional constitution/charter, and to give the binding interpretation of the regional constitution/charter.

Note that this list of powers is very narrow. Up until 2002, only the St. Petersburg Charter Court had this limited range of powers. The other functioning courts had additional powers such as participating in impeachment procedures, settling disputes between regional authorities, determining the constitutionality of political parties, and introducing legislation. In addition, the creation of these courts as a symbol of sovereign statehood and a mechanism for the protection of regional interests from federal intrusion required jurisdiction to invalidate federal laws and international treaties (Reference BobrovaBobrova 2001:146). These are important powers that could potentially influence regional policymaking processes.

Following the passage of the 1996 Law, some regions amended existing legislation on their constitutional courts while others simply copied the wording of the 1996 Law into their charters. Yet between 1997 and 2003, only in eight of them did regional constitutional/charter courts begin to function. Why so few? First, look at the rationale against such courts. As the idea of championing autonomy from the federal government became less accepted in Moscow, regional political elites did not need such attributes of independent statehood as regional courts. These elites witnessed the shift in the role of these courts—from the guardians of constitutions/charters protecting against federal encroachment to the arms of federal government ensuring the compliance of regional laws with federal laws.Footnote 9 This shift occurred because the federal government passed numerous statutes in the area of joint jurisdiction and insisted on their supremacy over regional laws. This shift culminated in October 2002, when the St. Petersburg Charter Court rejected—allegedly with the support of the federal government—the wish of the St. Petersburg governor to run for a third term (Reference Trochev, Solomon, Reddaway and OrttungTrochev & Solomon, forthcoming). Regional governors, who were much more active law makers than the legislatures, did not like the idea of local institutions checking the legality of their policies in addition to federal law-enforcement bodies (Reference Zrazhevskaia, Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiZrazhevskaia 2000:63; Reference Vedernikov, Derbenev, Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiVedernikov & Derbenev 2000:165). In those regions, where constitutional/charter courts supervise the impeachment procedure of governors, inoperative courts make it impossible to remove regional heads from office (Reference Bobrova and VolovichBobrova 1999:106, Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1999:30).

Among the most common reasons cited by regional politicians for not creating regional constitutional courts was a lack of funds to create them and the small workload of existing courts (Reference KalininKalinin 2000). Regional leaders labeled them “ordinary feeders for ordinary bureaucrats” (Reference ZadvorianskiiZadvorianskii 2000), “additional bureaucratic structures burdening the taxpayers” (Reference ZysmanovZysmanov 2000), and announced that there were no contradictions between regional laws and federal ones (Reference Mitiukov and BarnashovMitiukov & Barnashov 1999:285) and no conflicts between the legislative and executive branches of regional government.Footnote 10 Potential members of these courts (regional lawyers and law professors) who might have lobbied for their rapid creation distrusted the willingness and capacity of political elites to introduce these courts and demurred, complaining about the narrow scope of regional constitutional review allowed by the 1996 Law and the weak guarantees of judicial independence (Reference NazarenkoNazarenko 1997; Reference NevinskiiNevinskii 1999:6).

These political debates show that regional politicians began to pay attention to the actual work of the regional constitutional judiciary and learned how regional constitutional review could affect policy process in their regions (Reference SbornikSbornik materialov 1998; Problemy ukrepleniia konstitutsionnoi zakonnosti v respublikakh Rossiiskoi Federatsii 1998; Reference Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiMitiukov et al. 2000, Reference Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and Andreev2001). Naturally, regional law makers tended to look at the work of the constitutional courts in neighboring regions (Reference PaksimadiPaksimadi 2001). Perhaps this learning explains the failures to set up judicial review bodies in the two Russian regions with highly competitive political regimes operating in the context of uncertainty and regularly held elections. Volgograd (former Stalingrad) Province is one of these regions where politicians face enormous uncertainty and appear to settle their conflicts in local, regional, and federal elections, which in turn formalize/structure these conflicts with good prospects of democratic consolidation (Reference Gel'man, Ryzhenkov and BrieGel'man, Ryzhenkov, & Brie 2003). Current judicial empowerment theories suggest that these conditions favor the creation of judicial review, yet the Volgograd Province Charter, which has been amended twenty-four times since its adoption in July 1996, is unique due to its complete silence on the role of judicial branch in provincial governance (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 2002:470). This lack of attention to the institution of judicial review is despite the fact that the current speaker of the Volgograd Legislature is a 28-year-old lawyer!

Another Russian region where incumbents routinely lost gubernatorial and mayoral elections from 1991 to 2003 due to severe competition among provincial and federal political elites is Nizhnii Novgorod Province (Reference Gel'man, Ryzhenkov and BrieGel'man, Ryzhenkov, & Brie 2003; Reference SharafutdinovaSharafutdinova 2003). There, contrary to the expectations of mainstream judicial empowerment theories, the provincial legislature failed to create a charter court despite active efforts by its speaker, Anatolii Kozeradskii. He believed that this court would be a “serious court enforcing the law very strictly and making everyone behave in accordance with the law and not according to the one's wishes” (NTA 2001). His successor, Dmitrii Bedniakov, also favored a charter court as an attribute of provincial sovereignty and a mechanism for challenging regional laws in a civilized, impersonal way (Reference BedniakovBedniakov 2000).

While political uncertainty and vibrant electoral “markets” in Russian regions do not seem to promote judicial review, what about the regions where constitutional/charter courts began their work? In general, the process of creating regional constitutional courts became more protracted and more politicized during this wave. Sverdlovsk Province passed the Charter Court Act only in April 1997 (Zakon SO “Ob Ustavnom Sude Sverdlovskoi Oblasti” 1997), two and a half years after the Province Charter was enacted. Nine months later, Sverdlovsk Province Governor Eduard Rossel' presented five nominees for the bench of the Charter Court to the Provincial Legislature (Reference OblastnaiaOblastnaia gazeta 1998). In February 1998, the legislators appointed all but one candidate, and even he was appointed ten days later (Reference OblastnaiaOblastnaia Duma 1998a). In July 1998, after serious questioning the legislature approved a generous budget for the charter court, with a support staff of thirty-five (Reference OblastnaiaOblastnaia Duma 1998b). Although the incumbent governor, Rossel', won the 1995, 1999, and 2003 elections in runoffs, he had to run on a party platform and failed to become a dominant political actor in the province. His party had to compete in legislative elections against other political parties under the proportional representation system and seek the support of the autonomous local self-government units (Reference Gel'manGel'man 2000:60–01).

This unstable political party system may produce power diffusion and result in strong judicial review, according to current judicial empowerment theories. Indeed, the Sverdlovsk Province Charter Court is among the most active and accessible regional constitutional review bodies. However, most of the court's decisions have been against local governments in opposition to Rossel'. Moreover, in February 2002, the Charter Court Act was amended to allow appeals of the charter court decisions. These amendments allow the governor, legislative chambers, and the provincial ombudsman to demand the re-hearing of a case on broad grounds and minimize the discretion of the court in handling such appeals (Reference BobrovaBobrova 2002). The Sverdlovsk court case demonstrates the difficulties of judicial institution-building in the context of political power diffusion, yet this diffusion does not prevent politicians from using courts against their opponents and weakening judicial review.

The third wave also witnessed regional executives in Tatarstan and St. Petersburg vetoing bills on the regional constitutional courts. Mintimer Shaimiev, the Tatarstan president, vetoed a draft law on the Tatarstan Constitutional Court in summer 1998. He insisted on deleting the proposed powers of the court to suspend federal laws and bilateral treaties, a bold step that would not be tolerated by the federal government (Reference ChernobrovkinaChernobrovkina 1998). He also asked for the right to promote court clerks and warned that the 1998 budget had not allocated any money for the court. Parliament agreed with his proposals and passed the Constitutional Court Act in fall 1998, six years after the 1992 Tatarstan Constitution established this court. Still, six justices were appointed only in June 2000 (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 2000:56), when Russian President Putin launched his wide-ranging judicial reform and campaign to “harmonize” regional laws with the federal ones. It appears that this court was created to provide a venue for Tatarstan leaders to defend their autonomy-minded policies as their control over federal judiciary began to dissipate.Footnote 11 This case of the well-entrenched authoritarian executive designing judicial review without any real political opposition shows that politicians set up courts to retain and legitimize their ruling status.

The birth of the St. Petersburg Charter Court was even more difficult. Between 1998 and 2000, St. Petersburg Governor Vladimir Iakovlev had vetoed the draft laws on the court three times (Reference KalininKalinin 2000). Recently reelected with 73% of the vote, the governor managed to push his proposal disallowing access of the parliamentary minority to the court. However, he failed to gain the exclusive authority to nominate justices. According to Article 15 of the law, passed in May 2000, the legislature appoints justices upon nominations from any group of seven legislators, the Governor, and the judicial community (Zakon SP “Ob Ustavnom Sude Sankt-Peterburga” 2000). The governor and the opposition fought hard over nominations, and after two days of questioning sixteen nominees, the legislature finally appointed seven justices in September 2000 (Komitet po zakonodatel'stvu 2000; Reference Alekseeva and PolitykinAlekseeva & Politykin 2000). The governor's concerns were justified—only one of his six nominees was appointed to the bench and resigned from the court shortly afterward (Reference TravinskiiTravinskii 2000).

This long and noisy “birth” of this charter court was very different from the “quick and quiet” delivery of the regional constitutional courts in the previous waves because the governor failed to control the process of designing judicial review. Therefore, the St. Petersburg case appears to confirm current judicial empowerment theory that increased political competition and the power diffusion between the executive and the legislature result in the establishment of the constitutional court. However, contrary to mainstream theory, St. Petersburg's vibrant “electoral market” produced a court with the narrowest jurisdiction, restricted access, and the shortest judicial tenure (five years) among all Russian regions (see Table 2).

Federal Response

During this wave, regional politicians, judges, and lawyers received mixed signals about the future of regional constitutional justice from the federal government. In April 1998, the Russian Constitutional Court helped create the Consultative Council of the Chief Justices of Constitutional/Charter Courts (CCJ) meeting one to two times a year to discuss problems and coordinate their activities (Reference PolozheniePolozhenie 1998). At these CCJ meetings, federal authorities continued to stress that the regional courts should protect the supremacy of federal laws and assist federal government in its efforts to bring regional laws in line with federal ones (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 1998, Reference Kriazhkov2000; Reference StenogrammaStenogramma 2001). Russian President Vladimir Putin himself called for the inclusion of regional constitutional/charter courts in the process of bringing regional laws in line with federal standards (Reference PutinPutin 2000).

Mikhail Mitiukov, Putin's representative at the Russian Constitutional Court, and his support staff (the OPR) became the main vehicles of federal support for these courts. Since 1999, the OPR has been advertising its own model draft law on the constitutional/charter court to assist regional legislatures in drafting laws defining constitutional/charter courts (Reference Bobrova, Krovel'shchikova and MitiukovBobrova, Krovel'shchikova, & Mitiukov 2000) at numerous meetings on the problems of regional constitutional justice (Reference Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiMitiukov et al. 2000, Reference Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and Andreev2001). Moreover, Mitiukov made sure that the current phase of Russian judicial reform paid attention to the regional constitutional judiciary by relaxing the conditions for the nominees to the regional bench—age 25, with five years' work experience in the legal profession—and by integrating regional constitutional court judges into judicial self-government bodies (Zakon RF “O statuse sudei RF” 2001; Federalnyi zakon “Ob organakh sudeiskogo soobshchestva” 2002). This federal recognition brings regional judges closer to their federal colleagues, legalizes their status, and gives them a voice in the judicial community.

However, the prevailing direction of President Putin's federal and judicial reforms is the distrust of regional elites, the removal of the federal courts from regional control, and the elimination of contradictory judicial decisions (Reference SolomonSolomon 2002). This distrust also spills over to the regional constitutional courts and damages their reputation. In addition, the Russian Supreme Court continues to sponsor bills that would drastically narrow the jurisdiction of regional courts. Thus, in 1998, it sponsored a draft federal law authorizing regular courts to determine the constitutionality of regional laws (Reference GosudarstvennaiaGosudarstvennaia Duma 1999). Something similar happened in 2000, when the Russian Supreme Court introduced draft legislation on administrative courts, authorizing them to hear individual complaints against violations of regional charters and constitutions (Reference GosudarstvennaiaGosudarstvennaia Duma 2000). In both cases, the Federation Council, the upper chamber of the Russian legislature, vetoed the bills, not because its members, the regional heads, liked their constitutional courts, but because they disliked additional federal controls over their policies (Reference SovetSovet Federatsii 1999). Although the Russian Supreme Court responded that administrative courts would not encroach upon the jurisdiction of the regional constitutional judiciary (Reference RadchenkoRadchenko 2001), regional judges still opposed the idea of sharing their already narrow jurisdiction with one more judicial branch (Reference Geliakhov, Mitiukov, Kabyshev, Bobrova and ZaslavskiiGeliakhov 2001:211–17). Not surprisingly, the newly elected Russian Constitutional Court chairman, Valery Zorkin, urged President Putin and the Russian Supreme Court to accommodate the jurisdiction of the soon-to-be-established 521 federal administrative courts with the powers of already existing regional constitutional/charter courts (Reference PanshinaPanshina 2003).

Indeed, the Russian Constitutional Court ruled in October 1997 that Article 27 of the 1996 Law contained an exhaustive list of constitutional/charter court powers barring the regions from broadening them (Postanovlenie Konstitutsionnogo Suda RF ot 16.10.1997). This decision called into question the legality of all the other numerous powers of regional courts. Moreover, in April 2000, the Russian Constitutional Court gave the green light to Putin's campaign to “harmonize” regional laws and allow ordinary courts to declare regional laws “non-enforceable” (Postanovlenie Konstitutsionnogo Suda RF ot 11.04.2000). While regional constitutional court judges complained that this decision sharply decreased their caseload (Reference KriazhkovKriazhkov 2000:53; Reference StenogrammaStenogramma 2001), the Procuracy and federal courts used this decision broadly to invalidate regional constitutions and charters on the grounds of nonconformity with federal laws. As a result, in 2000–2003, all Russian regions that had constitutional/charter court statutes amended them to restrict their powers (see Table 2). Finally, in March 2003, the Russian Constitutional Court reversed its 1997 decision and ruled that the regions could expand the powers of their constitutional/charter courts to matters not authorized in federal law as long as the additional powers do not encroach upon the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary (Opredelenie Konstitutsionnogo Suda Rossiiskoi Federatsii ot 6.03.2003).

In short, the third wave began by the explicit federal authorization of regional constitutional courts and was fueled by federal and judicial reforms under President Putin. Federal involvement politicized the creation of these courts, rejected quasi-judicial review, and limited the powers of regional constitutional courts (Reference BobrovaBobrova 2001). Meanwhile, the functioning courts operated under extremely flexible constitutions/charters and the mixed support of the federal government. The third wave of subnational court-building partially confirmed the mainstream judicial empowerment thesis that power diffusion leads to judicial review—only in a single case, that of the St. Petersburg Charter Court. In the other cases, subnational judicial review was designed to either consolidate the power of dominant political actors or make up for their loss of control over the federal judiciary.

A Fourth Wave?

Given strong and contradictory federal attitudes toward regional constitutional justice, the next wave is likely to be triggered by both direct and indirect federal policy changes during President Putin's second term (2004–2008). The planned introduction of federal administrative courts in charge of politically sensitive cases (discussed in the previous section) is likely to ignore the jurisdiction of the existing regional constitutional judiciary and to generate “judicial hyperpluralism,” which would seriously damage the viability of subnational constitutional review in Russia.Footnote 12 Governors may prefer building amicable relations with these administrative courts if they expect them to be more powerful than the constitutional courts. However, regional elites may find it convenient to have their own courts to make up for the loss of control over federal judges because these courts are the courts of last resort. Regional courts could also legitimize policy choices of ruling elites, similar to the role of the advisory opinions of the state supreme courts in the United States. New courts are likely to begin their work in those provinces where regional legal elites can persuade governors of the usefulness of such courts, e.g., by strengthening gubernatorial control over revenues and local governments. The promise of federal funding for these courts would be the most crucial incentive for regional legal elites to lobby for them. This wave may be more politicized, as some regions would already have had long experience with constitutional courts, while other regions would begin to live under their own flexible constitutions/charters and their fledgling “guardians.” President Putin's sweeping reforms of Russian federalism and local government, as well as the election of regional legislatures under the proportional representation scheme, may produce both the demands for regional courts and the debates of the redundancy of these courts.

Conclusion: A Puzzle Ahead?

Why, by the end of 2003, did so few Russian regions (only fifteen out of eighty-nine) have functioning constitutional/charter courts in spite of legal authority to do so? Most regions chose not to set up such courts because dominant political actors were not willing to subject their policies to judicial oversight in the context of zigzag federal policies toward subnational constitutional review. In the first two waves, the federal government suspected that these courts would “legalize” the secessionist tendencies in the regions. In the third wave, regional governments feared the cooptation of these courts by the federal center and resisted funding them. In short, the Russian regional constitutional judiciary is weakly institutionalized and dependent on regional and federal authorities who constantly learn from each other to adapt institutional structures to their advantage.

My analysis supports the judicial empowerment thesis in that court-building is an elite-driven process of the political power distribution. Three waves of Russian experience with judicial review convincingly demonstrate that regional and federal political elites have dominated the process of empowering courts, a process that is “intimately related to the struggle for control over governmental power” (Reference North, Weingast, Alston, Eggertsson and NorthNorth & Weingast 1996:162). Contrary to existing judicial empowerment theories, Russia's regional constitution makers did not create the courts to minimize damage from electoral loss. In fact, most subnational constitutional courts were set up in the regions with well-entrenched incumbent political elites who stayed in power well after they created the courts (Reference KahnKahn 2002:Ch. 7).

Contrary to the theories that link democratization with constitutional courts, judicial review was not created (Nizhnii Novgorod and Volgograd), was weakened (Sverdlovsk), and was least accessible and least powerful (St. Petersburg) in the regions with highly contested elections and active political competition. Judicial review lasted several months and failed to take root in Chechnya and Mordoviia, where severe diffusion of political power resulted in the overthrow of constitutional order, not in the institutionalization of judicial review, as current judicial empowerment theories predict. Moreover, twelve constitutional courts were established and survived in the context of the “creeping authoritarianism” of constituent republics that threatens Russia's democratic transition (Reference KahnKahn 2002:4). In short, similar to the complexity of state-level constitution-making in the United States (Reference TarrTarr 1998), the evolution of constitutional “engineering” in Russian regions is far from being linear.

Why did authoritarian politicians set up powerful and accessible constitutional courts? Evidence from the Russian regions suggests that, initially, regional elites borrowed the idea of a constitutional review mechanism from the federal level to achieve “as much autonomy and control over local resources as possible, both to retain power and to run the republics in what they considered the appropriate way” (Reference McAuleyMcAuley 1997:108). Striving for a faster regional power consolidation meant that faster creation of the top regional institutions would entrench the power of current political elites. Regional legal experts, who designed constitutional/charter courts and later became their members, were able to convince politicians that constitutional review would enhance their power and succeeded in making their courts accessible to generate the caseload for their courts. This explains another piece of the “judicial review” puzzle: why, as the power of authoritarian governors grew, they allowed more accessible judicial review. To put it simply, judges need more litigation to prove the worth of their courts to the elites and to the public (Reference YamanishiYamanishi 2000). Later, the federal government encouraged the regional constitutional judiciary in its swift campaign to harmonize regional laws. This is why, during all three waves of regional constitutional/charter court formation, regional politicians allowed neither wide public discussion of their legitimacy nor popular elections of court members that could slow down the process of institution-building.

As Reference HirschlHirschl (2004) demonstrates, political elites in divided societies around the globe empower courts to consolidate and retain their power; this is not a unique Russian or “post-Communist” phenomenon. Nor is it exclusive only to culturally divided societies. In 1958, General de Gaulle created the French Conseil Constitutionnel with abstract constitutional review to guarantee the dominance of the executive over weak parliament (Reference StoneStone 1992:Ch. 2). Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbaev emulated this move in 1995 to dominate the legislature (Reference Olcott and TarasOlcott 1997:121; Reference Olcott2002:112). In 1979, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat introduced the Supreme Constitutional Court to legitimize his economic reforms (Reference HirschlHirschl 2000; Reference MoustafaMoustafa 2002). In none of these three cases did rulers fear losing elections, just as their colleagues in the Russian regions.

These similarities bring about yet another puzzle for future research. If, when it comes to courts, Russian politicians behave similar to their colleagues in “advanced” and not so “advanced” democracies, should we, then, expect Russian judges to behave the way judges abroad do? Should we expect the rise of the rule of law, Rechtstaat, “juristocracy” (Reference HirschlHirschl 2004), “judicial heteronomy” (Reference Ganev and SadurskiGanev 2002:263), a “war of courts” (Reference TrochevTrochev 2003), or a bundle of unintended consequences in Russia? We will not know the answers unless we begin to address the questions raised by the “constitutional ethnography” approach and to measure the actual impact of judicial review (judgments and their enforcement) on the political process, the capacity of the state, and on the well-being of ordinary citizens.