Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe psychiatric disorder with a massive global health burden, accounting for 7.4% (5.0–9.8) of disability-adjusted life years caused by mental and substance use disorders (Bhugra, Reference Bhugra2005; Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos2013). Compared with the general population, persons with schizophrenia have 3.7 times higher risk of premature death (Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup2015); men and women with schizophrenia have a reduced life-expectancy of around 19 and 16 years, respectively (Laursen, Reference Laursen2011). Among those with schizophrenia, the lifetime suicide rate is about 5% (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Pankratz and Bostwick2005; Hor and Taylor, Reference Hor and Taylor2010), and suicide is a major cause of premature death (Caldwell and Gottesman, Reference Caldwell and Gottesman1992; Brown, Reference Brown1997; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup2015). Prior suicide attempt is a major risk factor of suicide death (Hor and Taylor, Reference Hor and Taylor2010) and the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia ranged from 1.93% in Taiwan (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ma, Yen, Huang and Chiang2012) to 55.1% in the USA (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Mazonson and Pickar1984).

Several demographic and clinical factors are associated with the risk of suicide attempts in persons with schizophrenia. For example, patients with comorbid depressive symptoms, a family history of suicide and multiple hospitalisations (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Mazonson and Pickar1984; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ma, Yen, Huang and Chiang2012; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Al Jurdi, Zoghbi, Chen, Xiu, Tan, Yang and Kosten2013) are at a higher risk of suicide attempts (Roy, Reference Roy1983; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Mazonson and Pickar1984; Tremeau et al., Reference Tremeau, Staner, Duval, Correa, Crocq, Darreye, Czobor, Dessoubrais and Macher2005). Comorbid substance use (Togay et al., Reference Togay, Noyan, Tasdelen and Ucok2015; Fuller-Thomson and Hollister, Reference Fuller-Thomson and Hollister2016; Duko and Ayano, Reference Duko and Ayano2018) and more severe psychotic symptoms (Kao et al., Reference Kao, Liu, Cheng and Chou2012; Shrivastava et al., Reference Shrivastava, De Sousa, Karia and Shah2016) could also increase the risk of suicide attempts.

In order to develop effective preventive measures against suicide death, it is important to examine the epidemiology of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia. However, the reported prevalence rates have been inconsistent across studies, probably due to discrepancy in study sampling, duration and regions with different economic levels. A meta-analysis of suicide-related behaviours in China found that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was 14.6% in individuals with schizophrenia (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wang, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng, Meng, Yuan, Wang and Xiang2017). To date there is no meta-analysis on the epidemiology of suicide attempts in person with schizophrenia worldwide. We thus conducted a meta-analysis of observational studies to examine the prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia and associated factors.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and the protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the registration number of CRD42018112863.

Two investigators (LL and MD) independently searched the databases of Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of science and Cochrane from their respective commencement date until 12 June 2018 using the following search terms: ((attempted suicide) OR (suicide attempt*)) AND (schizophrenia OR (schizophrenic disorder) OR (schizoaffective disorder) OR (Dementia Praecox)) AND (epidemiology OR (cross-sectional study) OR (cohort study) OR prevalence OR incidence OR rate).

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were: (a) studies of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia; (b) cross-sectional or cohort studies (only the baseline data of cohort studies were analysed); (c) studies reporting prevalence of suicide attempts or providing relevant data which enabled the calculation of prevalence of suicide attempts; (d) studies published in English. Secondary analyses of medical records alone or studies with very small sample size, no timeframe or special populations (such as twins and samples in veteran/military hospitals) were excluded. Studies with mixed samples were included if data on schizophrenia and related diagnoses (e.g. schizoaffective or schizophrenia spectrum disorders) were reported separately. In order to increase homogeneity, only data of schizophrenia were extracted for analyses.

In the initial search, the titles and abstracts of publications were independently screened, and then the full texts were read by two investigators (LL and MD) to identify eligible studies. If there were multiple publications based on the identical study sample, only the one with the most complete information was analysed. Any discrepancies in study search and selection were resolved by a discussion or a consultation with a senior investigator (YTX).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Relevant data were independently extracted by the same two investigators (LL and MD), including country, study design, sample size and events of suicide attempts, mean age, gender proportion, source of patients (such as inpatients, outpatients, community or mixed), diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia, assessment tools and timeframe of suicide attempts. Study quality was also independently evaluated by the same two investigators using an eight-item instrument for quality assessment of epidemiological studies (Loney et al., Reference Loney, Chambers, Bennett, Roberts and Stratford1998). The items are shown in online Supplementary Table S1. The total score ranged from 0 to 8.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence and its 95% confidence intervals (CI) of suicide attempts were calculated using a random-effects model and Freeman Tukey double arcsine transformation (Freeman and Tukey, Reference Freeman and Tukey1950). Heterogeneity between studies was measured by τ 2 and I 2 statistic, with I 2> 50% indicating high heterogeneity (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

In order to explore the sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses (at least ten studies are needed) were performed. Subgroup analyses were conducted for categorical variables, such as gender (female/male); source of patients (inpatients/outpatients/community/mixed); economic group (low income/lower middle income/upper middle income and high income) and region (sub-Saharan Africa/East Asia and Pacific/South Asia/Europe and Central Asia/North America) according to the classification of the World Bank; assessment tools of suicide attempt (interview or and records/others). As recommended previously (Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011), at least ten studies are needed to perform meta-regression analyses. The potential moderating effects of continuous variables on lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts, such as sample size, mean age, the proportion of female patients, publication year and assessment score were also examined in this meta-analysis.

Funnel plots and Egger's regression model (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) were used to test publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was implemented by removing each study sequentially to assess the consistency of the primary results. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, New Jersey, USA) and STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) were used for analyses with the significance level as a p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Search results

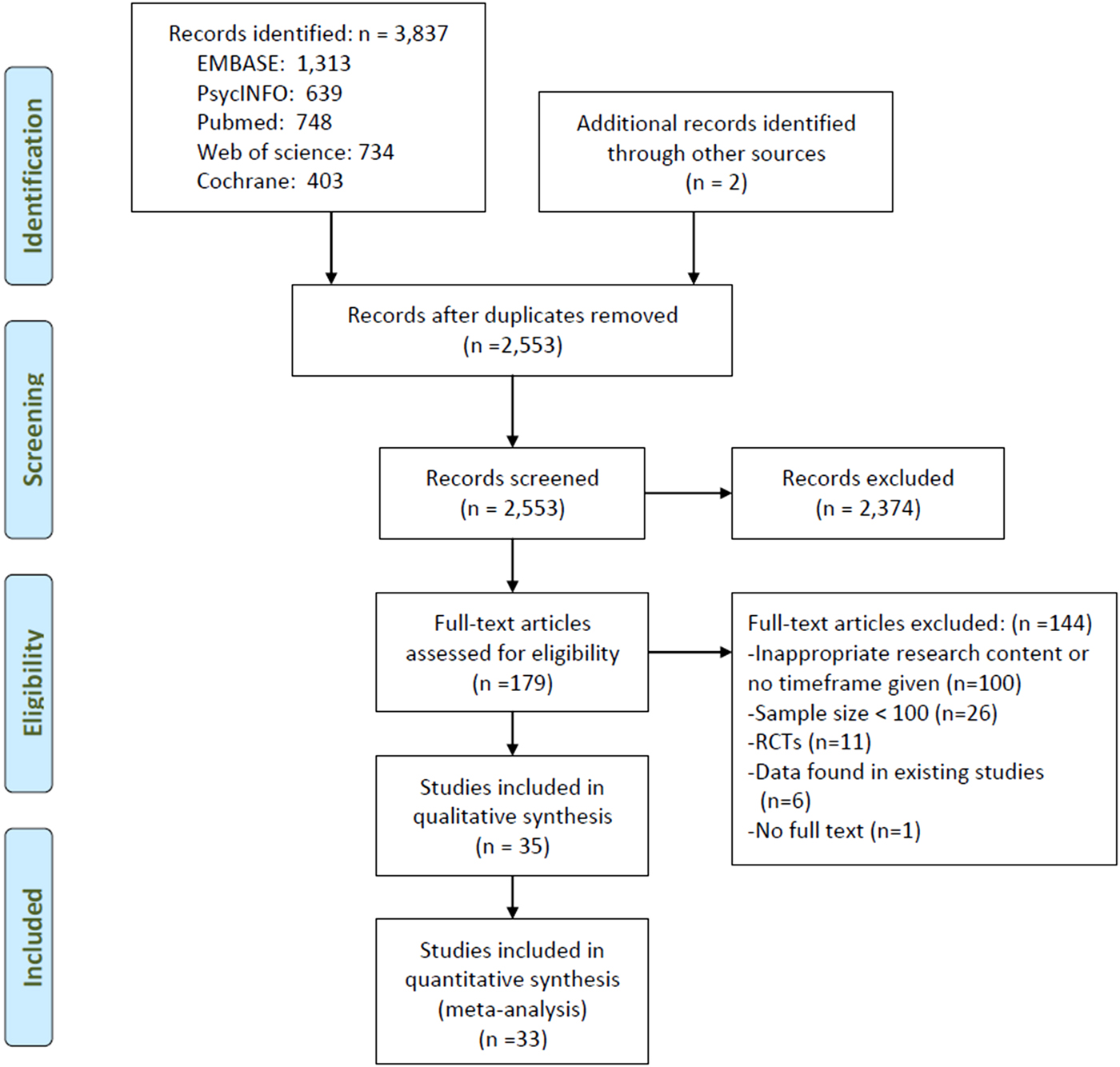

From a total of 3837 potential studies identified, 35 studies with 16 747 individuals with schizophrenia were included in the meta-analyses (Fig. 1). The full text of one study (Marcinko et al., Reference Marcinko, Popovic-Knapic, Franic, Karlovic, Martinac, Brataljenovic and Jakovljevic2008) could not be found and therefore was not included.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the selection of studies.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Study characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 40.1 years and women accounted for 37.1% of the whole sample. Twenty-eight studies (11 756 patients) reported the lifetime prevalence, one study reported both the lifetime and 1-month prevalence (Radomsky et al., Reference Radomsky, Haas, Mann and Sweeney1999), two studies reported the 1-year prevalence (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Gillespie, Epstein, Mao, Jiang, Chen, Cai and Mitchell2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ma, Yen, Huang and Chiang2012) and one study reported the 1-month prevalence of suicide attempts (Malandain et al., Reference Malandain, Thibaut, Grimaldi-Bensouda, Falissard, Abenhaim and Nordon2018), and two studies reported the prevalence of suicide attempts since illness onset (Prasad and Kellner, Reference Prasad and Kellner1988; Assefa et al., Reference Assefa, Shibre, Asher and Fekadu2012). One study from India (Shrivastava et al., Reference Shrivastava, De Sousa, Karia and Shah2016) and another from Greece (Andriopoulos et al., Reference Andriopoulos, Ellul, Skokou and Beratis2011) reported the 6-month prevalence and the prevalence of suicide attempts during the prodromal period, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

M, mean; NR, not reported; R, range; SA, suicide attempt; SCH, schizophrenia.

a Country: UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States.

b Diagnostic criteria (SCH): DIGS, The Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; ICD-10, the 10th Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health. Problems; RDC, The Research Diagnostic Criteria; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia;12 systems, 12 systems for diagnosing schizophrenia.

c Assessment tools (SA): CIDI, The composite international diagnostic interview; DIGS, The Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; SADS, Schedule for Affective. Disorders and Schizophrenia; SAIS, Suicide Attempts Investigation Schedule; SCID-I, The Structured Interview for Psychiatric Diagnosis.

Quality assessment of all the 35 studies ranged from 4 to 7; the details of quality assessment are shown in online Supplementary Table S1.

Prevalence of suicide attempts

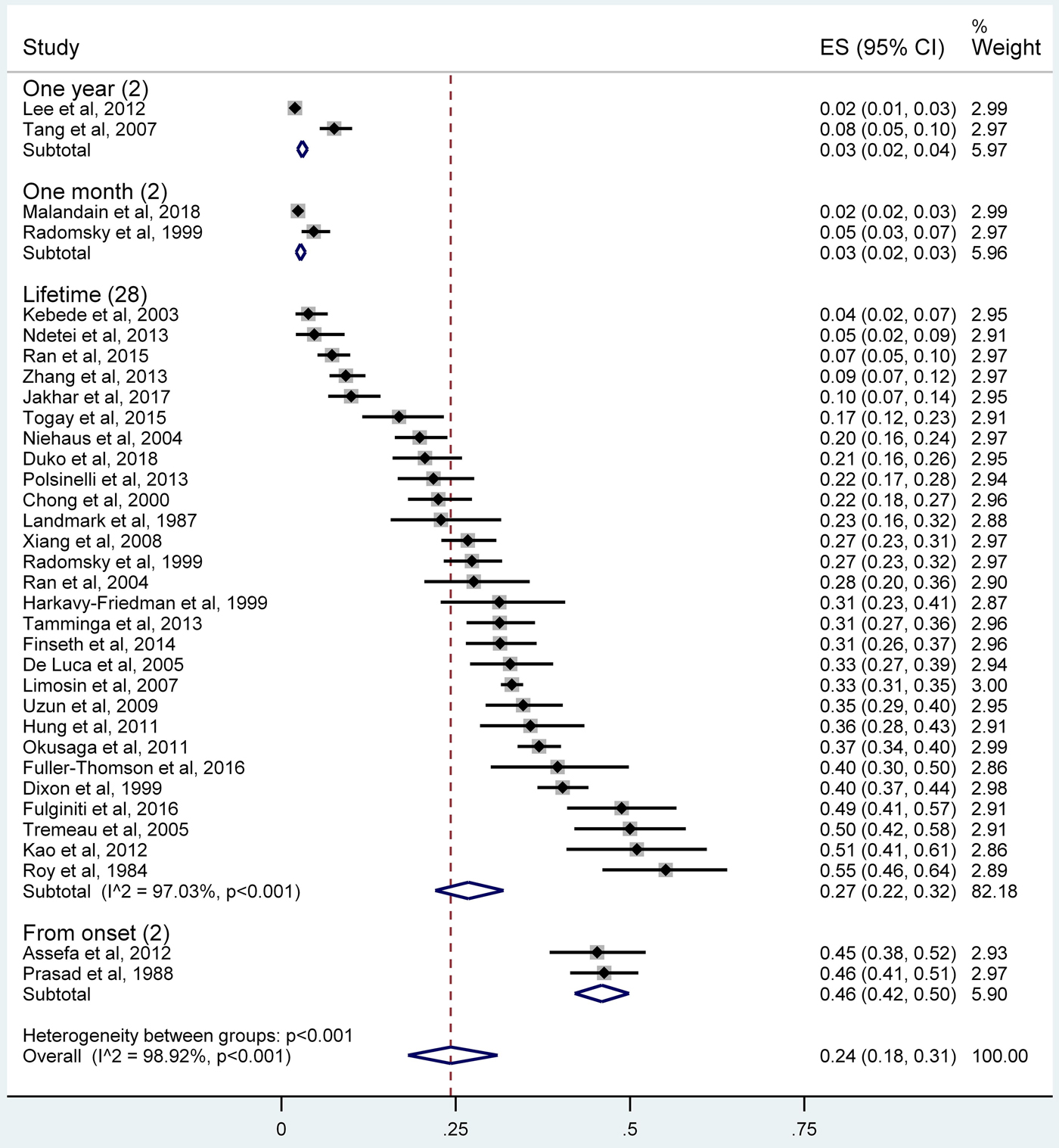

The pooled lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was 26.8% (95% CI 22.1–31.9%; τ 2 = 0.019, I 2 = 97.0%, p < 0.001), while the 1-year prevalence, 1-month prevalence and the prevalence of suicide attempts from illness onset in individuals with schizophrenia were 3.0% (95% CI 2.3–3.7%; τ 2 = 0.002, I 2 = 95.6%), 2.7% (95% CI 2.1–3.4%; τ 2 = 0.0002, I 2 = 78.5%) and 45.9% (95% CI 42.1–49.9%; τ 2 = 0, I 2 = 0), respectively (Fig. 2). The 6-month prevalence was 38% and the prevalence during the prodromal period was 7.5%.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of the prevalence of suicide attempts among individuals with schizophrenia.

Subgroup and meta-regression analyses

The subgroup analyses of lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts are shown in Table 2. The prevalence in high-income countries (35.3%, 95% CI 31.7–38.9%) was significantly higher than those in lower economic level countries (Q = 53.29, p < 0.001). Patients from North America (35.9%, 95% CI 29.8–42.2%) and Europe and Central Asia (32.2%, 95% CI 27.4–37.2%) were more likely to have suicide attempts than those from East Asia and Pacific (23.9%, 95% CI 14.3–35.2%), sub-Saharan Africa (11.0%, 95% CI 3.6–21.8%) and South Asia (10.0%, 95% CI 6.7–14.2%; Q = 32.83, p < 0.001). Early onset of illness group (41.8%, 95% CI 30.7–53.5%) had more frequent suicide attempts than late-onset patients (23.6%, 95% CI 12.1–37.6%; Q = 4.38, p = 0.04).

Table 2. Subgroup analyses of the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia

a SA, suicide attempt. Bolded values: p < 0.05.

Meta-regression analyses revealed that sample size (slope = 0.0001, p = 0.91), mean age (slope = −0.006, p = 0.42), the percentage of women (slope = 0.0008, p = 0.81), publication year (slope = −0.004, p = 0.187) and assessment score (slope = 0.04, p = 0.07) did not statistically moderate the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

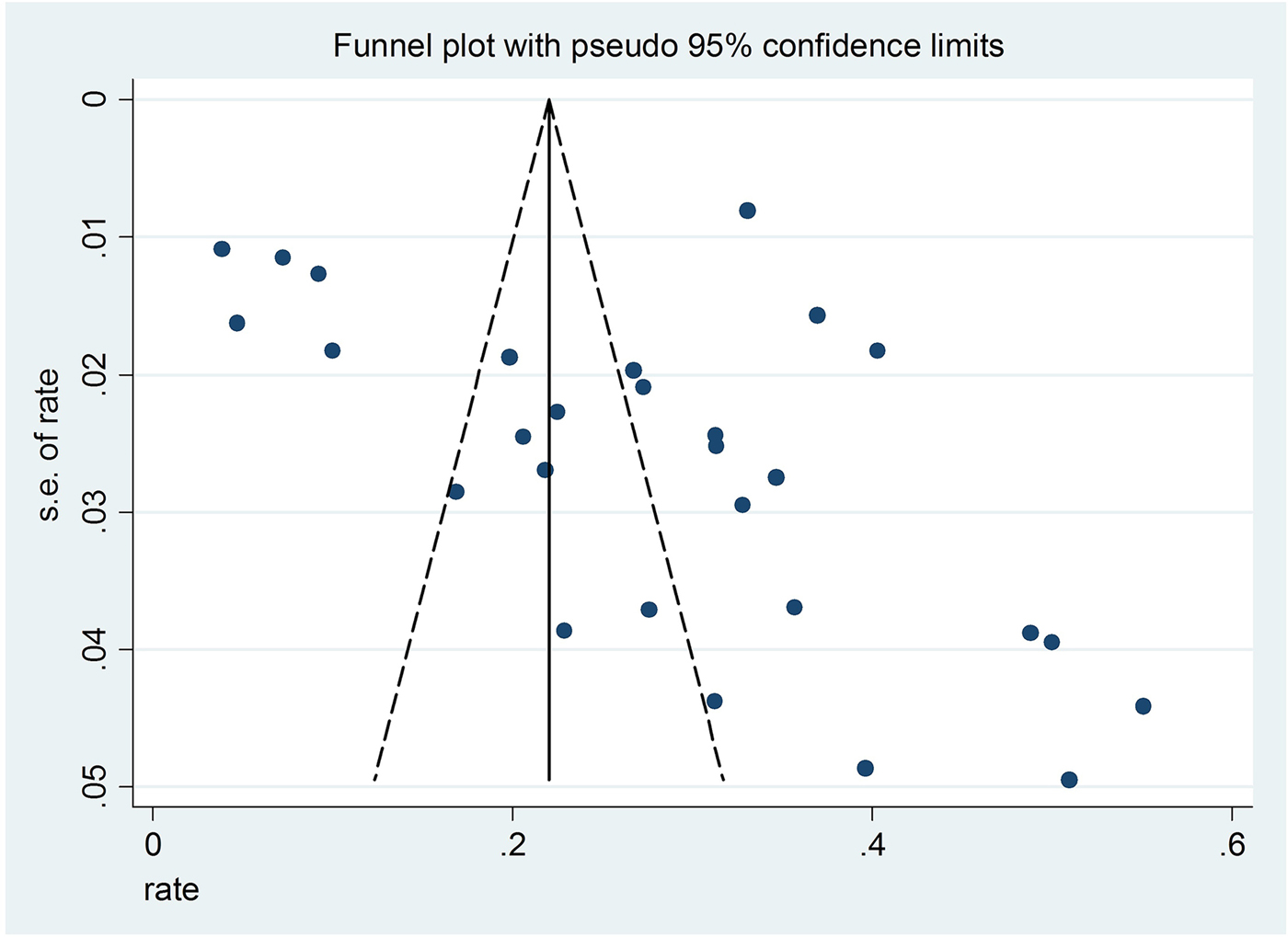

Sensitivity analyses found that after removing each study sequentially, the results of the lifetime prevalence did not change significantly. The funnel plot showed slight asymmetry, but the Egger's tests (t = 1.89, 95% CI −0.45 to 10.92, p = 0.07) did not reveal any publication bias (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Funnel plot of the 28 included studies reporting the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts.

Discussion

This was the first meta-analysis that examined the prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia across studies worldwide. This meta-analysis found that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was 26.8% (95% CI 22.1–31.9%), which is approximately two times higher compared to the corresponding figure (14.6%, 95% CI 9.1–22.8%) in China (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wang, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng, Meng, Yuan, Wang and Xiang2017). In addition, the prevalence in individuals with schizophrenia is much higher than the corresponding figure in general populations among 17 countries (2.7%) (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais, Bruffaerts, Chiu, de Girolamo, Gluzman, de Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Huang, Karam, Kessler, Lepine, Levinson, Medina-Mora, Ono, Posada-Villa and Williams2008) and in China alone (0.8%, 95% CI 0.7–0.9%) (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Zhong, Xiang, Ungvari, Lai, Chiu and Caine2015). Apart from the confounding effects of study characteristics, clinical factors, such as severity of psychiatric symptoms, comorbid disorders and the stigma and discrimination related to the illness, could contribute to the higher risk of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia (Hor and Taylor, Reference Hor and Taylor2010; Fuller-Thomson and Hollister, Reference Fuller-Thomson and Hollister2016; Duko and Ayano, Reference Duko and Ayano2018).

The pooled prevalence of suicide attempts from illness onset (45.9%) was highest, followed by the 6-month prevalence (38%) and the lifetime prevalence (26.8%). Prevalence estimates are significantly influenced by the illness severity and duration of the study. As in the case of this meta-analysis, only one study reported the 6-month prevalence of suicide attempt and two studies reported from-onset prevalence. This may bias the validity of the pooled prevalence of suicide attempts across studies with different timeframes and sampling. Other than the confounding effects caused by potential recall bias and small number of studies, various factors such as more severe psychotic symptoms, impaired global functioning from onset and stigma could increase the risk of suicidal behaviours in individuals with schizophrenia (Kaplan and Harrow, Reference Kaplan and Harrow1996; Radomsky et al., Reference Radomsky, Haas, Mann and Sweeney1999; Assefa et al., Reference Assefa, Shibre, Asher and Fekadu2012; Jakhar et al., Reference Jakhar, Beniwal, Bhatia and Deshpande2017). Patients with a younger age of illness onset had a higher risk of suicide attempts, which is consistent with some (Panariello et al., Reference Panariello, O'Driscoll, de Souza, Tiwari, Manchia, Kennedy and De Luca2010; Vinokur et al., Reference Vinokur, Levine, Roe, Krivoy and Fischel2014; Niehaus et al., Reference Niehaus, Laurent, Jordaan, Koen, Oosthuizen, Keyter, Muller, Mbanga, Deleuze, Mallet, Stein and Emsley2004), but not all studies (Popovic et al., Reference Popovic, Benabarre, Crespo, Goikolea, Gonzalez-Pinto, Gutierrez-Rojas, Montes and Vieta2014). In contrast, individuals with schizophrenia with late-onset illness may have relatively better developed social skills and functioning, and less violent or impulsive tendency, all of which could reduce the risk of suicidality (Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, DeBaryshe and Ramsey1989; Vinokur et al., Reference Vinokur, Levine, Roe, Krivoy and Fischel2014).

Individuals with schizophrenia in high-income countries were more likely to attempt suicide than those in the low- or/and middle-incomes countries, while those in North America or Europe and Central Asia had a higher prevalence of suicide attempts than in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and Pacific areas. The varying prevalence of suicide attempts across different regions could be partly explained by the differences in sociocultural and economic contexts and health care policies. For example, accessible mental health services and resources could effectively lower the risk of suicidal behaviours (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Lezotte, Jacobellis and Diguiseppi2006), while societal discrimination of individuals with schizophrenia could lead to internalised stigma and increase the risk of suicide attempt (Assefa et al., Reference Assefa, Shibre, Asher and Fekadu2012). In addition, religious and cultural factors are associated with the prevalence of substance abuse, such as alcohol and cocaine (Karch et al., Reference Karch, Barker and Strine2006), which could in turn increase the risk of suicide attempt (Prince, Reference Prince2018). Further, very few studies on suicide in schizophrenia have been conducted in low- and middle-income countries, which could lead to biased results. Of the included studies reporting lifetime prevalence, only two were conducted in low-income countries, two in lower middle income countries, one in South Asia and four in sub-Saharan Africa, which could reduce the reliability of the results. Apart from two studies in Turkey (upper middle-income country) (Uzun et al., Reference Uzun, Tamam, Ozculer, Doruk and Unal2009; Togay et al., Reference Togay, Noyan, Tasdelen and Ucok2015), studies in other countries were in the North America, Europe and Central Asia groups representing high-income countries. The relatively well-established reporting system for suicidal behaviours in these countries may be another reason for the higher prevalence of suicide attempts.

Gender difference in the prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia has been controversial. For example, in some studies, females had more frequent suicide attempts (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Gillespie, Epstein, Mao, Jiang, Chen, Cai and Mitchell2007; Fuller-Thomson and Hollister, Reference Fuller-Thomson and Hollister2016), while the opposite was found in other studies (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Mao, Chan, Chen and Conwell2015; Shrivastava et al., Reference Shrivastava, De Sousa, Karia and Shah2016). We did not find any gender difference, which is consistent with some (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wang, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng, Meng, Yuan, Wang and Xiang2017), but not all studies (Hawton, Reference Hawton2000). Unlike the findings in previous studies (Hor and Taylor, Reference Hor and Taylor2010; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Al Jurdi, Zoghbi, Chen, Xiu, Tan, Yang and Kosten2013), we did not find any association between younger age and risk of suicide attempts. Different illness phases and settings (e.g. inpatients v. outpatient settings) are associated with different risk of suicide for individuals with schizophrenia (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Gates, Whitaker and Cotton1985). However, subgroup analysis did not find any difference in suicide attempt prevalence between inpatients, outpatients and those in community.

Several methodological limitations need to be addressed. First, only studies published in English were included. Second, subgroup and meta-regression analyses were only performed for lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts due to a low number of studies of other timeframes. Third, some factors related to suicide attempts, such as prescription of antipsychotic medications, psychiatric comorbidities and number of admissions (Fuller-Thomson and Hollister, Reference Fuller-Thomson and Hollister2016), were not examined due to lack of data in the included studies. Fourth, similar to other meta-analyses (Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Ganapathy, Marwaha, Large, Birchwood and Singh2013; Long et al., Reference Long, Huang, Liang, Liang, Chen, Xie, Jiang and Su2014; Li et al., Reference Li, Cao, Zhong, Ungvari, Chiu, Lai, Zheng, Correll and Xiang2016; Mata et al., Reference Mata, Ramos, Bansal, Khan, Guille, Di Angelantonio and Sen2015), high heterogeneity remained in the subgroup analyses, which is difficult to avoid in a meta-analysis of observational surveys. The heterogeneity was probably related to certain unmeasured factors, such as severity of psychotic symptoms, family history of psychiatric disorders and suicide, use of psychotropic medications and access to health services. In addition, only individuals with schizophrenia were included in this study, therefore the findings cannot be generalised to those with schizoaffective or schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Finally, only one study reported the 6-month prevalence of suicide attempt, two studies reported the 1-year prevalence, two studies reported the 1-month prevalence and two studies reported from-onset prevalence. Hence, the small number of studies in these timeframes may bias the validity of the pooled prevalence of suicide attempts.

In conclusion, suicide attempts are common in individuals with schizophrenia, especially those with an early age of onset and living in high-income countries and regions. Careful screening and effective preventive measures should be implemented routinely for this population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000313.

Availability of data and materials

All the data involved have been included in Tables and Figures of this manuscript.

Author ORCIDs

Yu-Tao Xiang, 0000-0002-2906-0029.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

The study was supported by the University of Macau (MYRG2015-00230-FHS; MYRG2016-00005-FHS), National Key Research & Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC1307200), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (No.ZYLX201607) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals' Ascent Plan (No. DFL20151801).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.