In his Telluris Theoria Sacra and its English translation The Theory of the Earth (1681–90), the English clergyman and schoolmaster Thomas Burnet (c.1635–1715) constructed a geological history from the Creation to the Final Consummation, positing predominantly natural causes to explain biblical events and their effects on the Earth and life on it. According to Burnet, the biblical Chaos was a mass of particles descending toward the centre. The densest descended first and compacted to form the core. The remainder separated into an inner sphere of liquid and an outer sphere of air, each containing solid particles which were lighter than those at the centre and descended more slowly. The liquid separated into two regions, an inner sphere containing denser waters and an outer sphere composed of lighter oils. The particles in the air descended and mixed with the oil and hardened to form a solid, uniform crust above the water. Owing to its uniformity, the Earth's mass was evenly distributed and its axis perpendicular to the ecliptic. The constant heat of the Sun on the equator created fissures in the crust, causing it to rupture and descend into the water. This brought about the Deluge and gave the Earth its present terraqueous and mountainous form, with its mass now unevenly distributed and axis inclined to the ecliptic.Footnote 1 The present Earth will be destroyed by volcanic eruptions, subterraneous combustions and ‘fiery meteors’, reducing it to a second chaos out of which a new Earth will form in a manner similar to the first. This new Earth, Burnet concluded, will be home to the Kingdom of Christ during the Millennium, after which it will burn again, leave the vortex of the Sun, and become a star.Footnote 2

The influence of René Descartes (1596–1650) on Burnet's theory will be immediately recognizable to anyone familiar with Cartesian natural philosophy and is well known to historians.Footnote 3 My focus in this article is on a more foundational issue, namely why Burnet insisted on explaining biblical events primarily in terms of natural rather than miraculous causes. This, too, has been construed by some historians as an essentially Cartesian commitment.Footnote 4 It was also the interpretation of many of Burnet's contemporaries.Footnote 5 On this reading, Burnet adhered to a Cartesian style of explanation in which there was no place for miracles. In this article, I propose a different interpretation. Burnet's use of natural over miraculous causes, I argue, was not grounded in a commitment to a Cartesian style of explanation but in an ‘anti-voluntarist’ or ‘intellectualist’ theology which he inherited from the Cambridge Platonists and Latitudinarians.Footnote 6 For Burnet, God's will is constrained by his wisdom and goodness, and since it is contrary to his wisdom to employ greater means than are necessary when executing his will, he will not intervene in the world if natural causes are sufficient. This, rather than Burnet's Cartesianism, was the basis of his methodological principle that, when theorizing about biblical events, we should appeal primarily to natural causes and not invoke miracles unnecessarily.

Burnet's anti-voluntarism also underpinned his view of the miraculous elements that were – or, in the case of future occurrences, will be – involved in biblical events. This is because God's wisdom for Burnet also places constraints on the kinds of miracles he does employ. Where natural causes are insufficient, it is nevertheless still wiser for God to use subordinate means than to intervene directly in nature unless the latter is strictly necessary. These means, the means by which virtually all miracles are enacted in Burnet's view, consist in the ministry of angels. From this, Burnet derived another, analogous methodological principle. If natural causes are insufficient, and we must appeal to miracles to make sense of biblical events, then we should not invoke God's direct omnipotence if the ministry of angels is sufficient.

This interpretation of Burnet's commitment to natural over miraculous causes – and of his parallel commitment to angelic over direct divine intervention – contrasts with the view that he was simply following the Cartesian method of explaining events in terms of natural processes. Indeed, Burnet's foundations here are in important respects decidedly un-Cartesian. First, Descartes had espoused a radical form of theological voluntarism according to which the very nature of wisdom is dependent on God's arbitrary will and not something antecedent to it to which he must conform. Second, Burnet's and Descartes's views of providence were based on distinct attributes of God, and these attributes had quite different implications regarding the place of miracles in the providential order. So although many details of the Theory were undoubtedly underpinned by Cartesian principles, it was a markedly different set of principles that grounded Burnet's commitment to natural – and, where these fail, angelic – causes.

In appealing to both natural causes and spiritual agents, Burnet's Theory embodied two distinct but often complementary approaches that Scott Mandelbrote has identified in seventeenth-century natural theology. One of these aimed to confute atheism by emphasizing law-like regularities as evidence of design in nature. The other sought to combat materialism by highlighting the existence of spiritual phenomena.Footnote 7 Burnet's main emphasis was on the former. Yet he also believed in the latter and made substantial use of it both in the Theory itself and when defending the work against critics. The laws of nature – and their remarkable timing in bringing about events recorded and prophesied in Scripture – constituted the core of his natural theology. Natural laws, however, could only achieve so much. Sometimes a different kind of divine influence was required, and this Burnet found in the realm of spirits. Unlike some of his contemporaries who gave spirits a more pervasive role in nature, Burnet maintained that God uses them only on those rare occasions where mechanical causes fall short. To use them otherwise would be to employ a higher power than is necessary, something that is contrary to God's wisdom and therefore something God cannot do.

Burnet, the Cambridge Platonists and the Latitudinarians

Burnet was born in Croft-on-Tees around 1635 and entered Clare Hall, Cambridge, in 1651. Though officially a student of the theologian William Owtram (1626–79), he worked more closely with the Cambridge Platonist Ralph Cudworth (1617–88) and Latitudinarian divine John Tillotson (1630–94). He followed Cudworth to Christ's when Cudworth became master of the college in 1654; became a fellow in 1657; and, alongside another Cambridge Platonist, Henry More (1614–87), taught the new Cartesian philosophy at the college. In 1678, after a decade-long sabbatical, he resigned from his position at Cambridge and relocated to London. Here, in 1681, owing to Tillotson's recommendation, he became personal tutor to the Earl of Ossory, grandson of the Duke of Ormond, and became master of the Charterhouse school in 1685 under the patronage of Ormond. Following the Revolution of 1688–9, he was appointed chaplain-in-ordinary to King William III under Tillotson's influence and succeeded Tillotson as clerk of the closet in 1691 when Tillotson became Archbishop of Canterbury. He looked a likely successor here, too. But by the time of Tillotson's death in 1694 his heterodox views on Scripture had been made clear in his Archaeologiae Philosophicae (1692), a controversial defence of the Theory in which he denied the Mosaic account of the Creation and Fall in Genesis 1–3. He was passed over for the position, forced to resign from his duties at court, and returned to the Charterhouse, where he remained until his death in 1715.Footnote 8

The Cambridge Platonists were a group of philosopher–theologians, all but More (and Cudworth after moving to Christ's) being fellows of Emmanuel College. In addition to Cudworth and More, the main members were Nathaniel Culverwell (1619–51), John Smith (1618–52), Peter Sterry (1613–72), and Benjamin Whichcote (1609–83).Footnote 9 Culverwell and Smith both died around the time Burnet entered the university, and there is no known connection between Burnet and Sterry and Whichcote, so I shall limit my discussion here to the work of Cudworth and More. Sarah Hutton has described Cudworth's and More's philosophy as a kind of ‘modified Cartesianism’ in that both adopted substantial components of Descartes's philosophy but eschewed such tenets as the rejection of final causes and what they interpreted as an extreme form of theological voluntarism. More also rejected Descartes's view that only matter is extended, maintaining that spiritual substance is also extended and positing an ‘immaterial extension’ in which material extension is contained. And both rejected his mechanistic world view, proposing an immaterial principle that governs the physical world – ‘plastic nature’ for Cudworth and ‘spirit of nature’ or ‘hylarchic principle’ for More.Footnote 10 As several historians have noted, this selective use of Cartesian ideas was common among English natural philosophers. Though widely read and disseminated in England, Descartes's philosophy was never embraced in its entirety. Like many others, Cudworth and More were enthusiastic readers, but they were not uncritical. Even More, during his early career when he was yet to fully discern its dangerous theological implications and was busy popularizing it in Cambridge, rejected many tenets of the Cartesian world view.Footnote 11

Burnet's Cartesianism was similar in certain respects. He did not reject final causes and appealed to them extensively in the first volume of the Theory.Footnote 12 And although he did not argue explicitly against Descartes's voluntarism, the anti-voluntarist sentiments in his work that I discuss below surely imply that he did not accept it. His Cartesianism was, however, substantially less modified than Cudworth's and More's. Unlike More, he accepted the Cartesian view that only matter is extended and appealed to it in the Theory to argue against the miraculous creation and annihilation of water at the Deluge.Footnote 13 And unlike both, he maintained a mechanistic physics. He did, as I shall discuss below, believe that non-extended spiritual substances such as angels and human souls effect changes in the material world. But he saw these phenomena essentially as peculiarities in what is otherwise a world governed by mechanism and did not propose any kind of general immaterial principle governing the physical world, talking instead in terms of inert matter created and set in motion by God.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, as John Henry has emphasized, Burnet was not straightforwardly a Cartesian, and his work fits the overall picture of the reception of Cartesianism in England that Henry and others have reconstructed.Footnote 15 He borrowed more substantially from Descartes and was less cognizant of the theological dangers of Cartesianism than his mentors at Cambridge, and he continued to defend Cartesian physics and cosmology at the end of the century when most had abandoned them.Footnote 16 But, like others in England, he used Descartes selectively. He never fully embraced the Cartesian system and rejected both important foundational commitments and significant physical details of Descartes's natural philosophy.

Turning now to the Latitudinarians, the term ‘Latitudinarian’ or ‘latitude man’ was originally a pejorative invented during the Restoration by High Churchmen to describe a group of divines who had conformed to the Interregnum Church and had justified doing so on the grounds that they only compromised on inessential doctrines while remaining true to the fundamentals of the Christian faith.Footnote 17 The term was intended to connote broadness, flexibility and inclusivity in matters of doctrine, liturgy and creed. As Joseph Glanvill (1636–80), himself a prominent Latitudinarian, sympathetically summed it up, the group were

a sort of men, whose Antipathy to the Fanatical Genius of the Age was quickly noted, and no sooner known than branded with Nick-names very odious, as the Custom then was … One of the most Common names given them was Latitudinarian from a word that signifies compass or largeness, because of their opposition to the narrow stingy Temper then called Orthodoxness.Footnote 18

The divines listed as the most prominent Latitudinarians in Martin Griffin's classic study of the subject are Glanvill, Tillotson, Gilbert Burnet (1643–1715), Edward Fowler (1632–1714), William Lloyd (1627–1717), Simon Patrick (1626–1707), Edward Stillingfleet (1635–99), Thomas Tenison (1636–1715) and John Wilkins (1614–72), to whom Griffin adds several less prominent figures.Footnote 19 Other authors have applied the term to a broader set of seventeenth-century thinkers.Footnote 20 The Latitudinarians were mostly educated in Cambridge but left the university to seek preferment in London, the vast majority of them taking up positions in the Church.Footnote 21 Widely regarded as heterodox during the Restoration, their fortunes changed following the Revolution of 1688–9 when several of them, being the most vocal supporters of the Revolution among the clergy and having presented concerted opposition to James II's Catholicizing policies, were promoted to bishoprics.Footnote 22

During the Restoration, the term ‘Latitudinarian’ was applied both to this younger generation and to the Cambridge Platonists. As the century progressed, it became increasingly applied exclusively to the former group.Footnote 23 This variation is reflected in historical studies, with some historians characterizing the Platonists as Latitudinarians and others distinguishing between the two groups.Footnote 24 Burnet, too, is sometimes presented as a Latitudinarian and the Theory as a Latitudinarian work. Johannes van den Berg, for example, refers to ‘Thomas Burnet, master of the Charterhouse’ as ‘a prominent Latitudinarian’.Footnote 25 John Gascoigne identifies the Theory as ‘the most thoroughgoing attempt by a Cambridge Latitudinarian to demonstrate the conformity of Scripture with the “new philosophy”’.Footnote 26 And Richard Olsen describes it as ‘characteristic of seventeenth-century Latitudinarian natural theology’.Footnote 27 Scott Mandelbrote, on the other hand, suggests that the portrayal of Burnet as ‘a Latitudinarian divine’ is largely a result of confusion with ‘his more famous namesake’, Gilbert.Footnote 28 And several treatments of seventeenth-century Latitudinarianism – including studies of Latitudinarianism and science – do not mention him.Footnote 29

Mandelbrote is right that Burnet is often confused with Gilbert Burnet, and indeed he cites several examples of such confusion.Footnote 30 Notwithstanding this, however, the characterization of Burnet as a Latitudinarian is not entirely without warrant. As well as championing several core Latitudinarian principles, Burnet was, of course, close with Tillotson, one of the most prominent of the group. During the 1680s, Burnet, like those more widely considered Latitudinarians, opposed King James II, becoming involved in a dispute with the Crown over James's appointment of a Catholic at the Charterhouse.Footnote 31 And as I noted above, following the Revolution, he benefited from the Latitudinarians’ fortunes, being appointed chaplain-in-ordinary and clerk of the closet to the new king. As Gascoigne acknowledges, however, Burnet's preferments resulted principally from Tillotson's patronage. When Tillotson died, his prospects for further advancement ended abruptly, suggesting that other Latitudinarians, who by now were heavily influential in the Church, had less truck with his heterodox ideas.Footnote 32

Further discussion of the minutiae of Latitudinarianism is beyond the scope of this article. What is important for our purposes is that the Cambridge Platonists and Latitudinarians held several important theological commitments in common, and various of these are prominent in Burnet's work. The tenets of Cambridge Platonism and Latitudinarianism that are most salient in Burnet's writing are an advocacy of the use of reason in religion, an insistence on the compatibility of reason and religion, an enthusiasm for the ‘new science’ and for the application of natural philosophy to apologetic purposes, an emphasis on the fundamentals of Christianity over inessential doctrines, an emphasis on God's wisdom and goodness over his will and power, and an anti-voluntarist theology insofar as God's will and power are constrained by his wisdom and goodness.Footnote 33

The foregoing tenets play important and closely interrelated roles in Burnet's work. He was, of course, highly enthusiastic about the ‘new science’, and the use of reason in religion and the application of natural philosophy to apologetic purposes were precisely what he was engaged in in the Theory. He wanted to make biblical events explicable in terms of natural causes in order to vindicate sacred history and show that reason and philosophy are consistent with Scripture. This essential compatibility of reason and Scripture was strongly emphasized at the beginning of the work.Footnote 34 For Burnet, the necessary agreement between reason and Scripture derived from both being given to us by God. God cannot contradict himself, and so reason, if used correctly, cannot contradict Scripture. This meant that truths arrived at through reason which appear to contradict Scripture do not in fact do so. In such cases, rather, Scripture has been misinterpreted and must be reinterpreted to conform with reason. The core guiding principle in such reinterpretations for Burnet was derived from an emphasis on the fundamentals of Christianity over inessential doctrines, a key fundamental being the attributes of God, and in particular his wisdom and goodness. Interpretations of Scripture must not contradict these fundamentals. Interpretations which do contradict them, moreover, cannot be correct, and the relevant passages must be reinterpreted to conform to them.

Anti-voluntarism and natural versus extraordinary providence

The above principles would be carried to their logical – and, many would believe, heretical – conclusion in the Archaeologiae in Burnet's denial of the literal sense of Genesis 1–3, which he thought was incompatible with both reason and the fundamentals of the Christian faith, and especially the wisdom and goodness of God – as I discuss below, Burnet's anti-voluntarism is evident in this work, too.Footnote 35 Here, though, my focus is on the Cambridge Platonists’ and Latitudinarians’ anti-voluntarism and its influence on Burnet's commitment to natural over miraculous causes in the Theory. The anti-voluntarism which the Platonists and Latitudinarians adopted was first articulated in early modern England by the theologian Richard Hooker (1554–1600) in his Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie (1594). For Hooker, God's attributes implied that he is not wholly free, for he cannot act in a way that is contrary to them. He has imposed a law upon himself ‘where-by his wisdome hath stinted the effects of his power in such sort, that it doth not worke infinitely’.Footnote 36 This anti-voluntarism was pitted in the late sixteenth century by Hooker and during the mid- to late seventeenth century by the Platonists and Latitudinarians against the Calvinist voluntarism that had been dominant since the Reformation.Footnote 37

Burnet most likely inherited his anti-voluntarism primarily from Cudworth and Tillotson, respectively the Cambridge Platonist and Latitudinarian with whom he was most closely associated during his formative years at Cambridge. Of all the Cambridge Platonists, writes Hutton, Cudworth provided ‘the most systematic statement of their anti-voluntarism’.Footnote 38 Cudworth's anti-voluntarism is expressed at several points in his True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678), the only work he published during his lifetime.Footnote 39 It is also articulated at length in his posthumously published writings, with which Burnet was likely familiar given his proximity to Cudworth during his time at Cambridge.Footnote 40 For Cudworth, properties like goodness and wisdom must exist independently of God, for if something is to be said to possess these attributes, then it must conform to some pre-existing set of standards. If their nature depended merely on God's arbitrary will, then he could not in any meaningful sense be said to possess them, for if he had freely chosen their nature, then his possessing them would be trivial. Given that he does possess them, he cannot act in a way that is contrary to them. His will is constrained by these other aspects of his nature, which must conform to some absolute standard of goodness and wisdom. ‘There is a nature of goodness, and a nature of wisdom’, wrote Cudworth in his Treatise on Freewill, ‘antecedent to the will of God which is the rule and measure of it’.Footnote 41

The Latitudinarians’ anti-voluntarism was heavily influenced by Cudworth and the Cambridge Platonists and was communicated in similar terms throughout Tillotson's sermons on the nature of God.Footnote 42 ‘The Soveraignty of God’, he stated in one, ‘doth by no means set him above the Eternal Laws of Goodness, and Truth, and Righteousness’.Footnote 43 And in another:

we cannot, from the soveraignty of God, infer a right to do any thing that is unsuitable to the Perfection of his Nature; and consequently … it would be little less than a horrid and dreadful Blasphemy, to say that God can, out of his Soveraign Will and Pleasure, do any thing that contradicts the Nature of God, and the essential Perfections of the Deity; or to imagin that the Pleasure and Will of the Holy, and Just, and Good God is not always regulated and determined by the essential and indispensable Laws of Goodness, and Holiness, and Righteousness.Footnote 44

The implications of this anti-voluntarism for Burnet's Theory, however, are most clearly prefigured in the work of Glanvill, the Latitudinarian who was closest, both intellectually and socially, to the Cambridge Platonists.Footnote 45 Glanvill's influence on Burnet has been discussed by William Poole, who has focused on his impact on Burnet's use of Cartesian cosmology and on his model of the apocalypse.Footnote 46 As Poole observes, the work on which Burnet principally drew was Glanvill's Lux Orientalis (1662), a book primarily concerned with the pre-existence of souls. Though Burnet did not explicitly cite the book in the Theory, the striking similarities between the two texts in several areas make it clear that he was heavily influenced by it.Footnote 47 What I want to draw attention to here are the parallels between Glanvill's and Burnet's views of natural providence and the anti-voluntarism that underpins them. Here the two authors’ discussions are so closely aligned that it is impossible not to conclude that Burnet's position owed much to Glanvill, despite his lack of acknowledgement.

As Jackson Cope has observed, Glanvill's anti-voluntarism effectively barred God from intervening directly in the world. God, for Glanvill, is bound by his nature to work through ‘second causes’. God's providence is therefore primarily natural providence.Footnote 48 Glanvill's statement of this is so similar to Burnet's as to warrant quoting at length. ‘There is an exact Geometrical justice’, he wrote,

that runs through the universe, and is interwoven in the contexture of things. This is a result of that wise and Almighty Goodness that praesides over all things … And that benign wisdom that contrived and framed the natures of all beings, doubtlesse so provided that they should be suitably furnisht with all things proper for their respective conditions. And that this Nemesis should be twisted into the very natural constitutions of things themselves, is methinks very reasonable; since questionlesse, Almighty wisdom could so perfectly have formed his works at first, as that all things that he saw were regular, just, and for the good of the universe, should have been brought about by those stated Laws, which we call nature; without an ordinary engagement of absolute power to effect them … For this looks like a more magnificient apprehension of the Divine power and Praeexistence, since it supposeth him … to have foreseen all future occurrences, & so wonderfully to have … constituted the great machina of the world that the infinite variety of motions therein, should effect nothing but what in his eternal wisdom he had concluded fit and decorous.

God's direct intervention, then, for Glanvill, is contrary to his wisdom:

to engage gods absolute and extraordinary power … is meseems to think meanly of his wisdome; As if he had made the world so, as that it should need omnipotence every now & then to mend it, or to bring about those his destinations, which by a shorter way he could have effected, by his instrument, Nature.Footnote 49

For Glanvill, this insistence on natural over extraordinary providence formed the basis of an important methodological principle. When inquiring into such things as the embodiment of souls, we must appeal to natural rather than miraculous causes, for as God's nature binds him to work through natural law rather than direct intervention, so too, when theorizing about these processes, we must do so in terms of the former rather than the latter.Footnote 50

In Burnet, a similar emphasis on God's wisdom and a similar anti-voluntarism give rise to a view of providence which strongly echoes that of Glanvill. For Burnet, God's wisdom effectively prevents him from intervening directly in the natural world, for where other, subordinate means of bringing about his will are available, it is contrary to his wisdom to intervene directly rather than employ these means. ‘Wisdom’, wrote Burnet, ‘consists in the conduct and subordination of several causes to bring our purposes to effect’, and ‘what is dispatched by an immediate Supreme Power, leaves no room for the exercise of Wisdom’.Footnote 51 The instruments of the divine will that are most consonant with God's wisdom are natural causes. Providence, then, is predominantly natural providence. Natural providence consists in ‘[t]he Form or Course of Universal Nature, as actuated by the Divine Power: with all the Changes, Periods, and Vicissitudes that attend it, according to the method and establishment made at first, by the Author of it’Footnote 52 – in other words, the laws of nature, contrived by God in the beginning. Where God's will can be effected via natural law, it is contrary to his wisdom to employ a higher power. As in Glanvill, this rule to which God is bound by his essential nature becomes for Burnet a crucial methodological principle in constructing his theory. God does not intervene in the world if natural causes are sufficient. Neither, therefore, should we appeal to a miraculous power to explain events which can be explained in terms of natural causes, for

if we would have a fair view and right apprehensions of Natural Providence, we must not cut the chains of it too short, by having recourse, without necessity, either to the First Cause, in explaining the Origins of things: or to Miracles, in explaining particular effects. This, I say, breaks the chains of Natural Providence, when it is done without necessity, that is, when things are otherwise intelligible from Second Causes … The Course of Nature is truly the Will of God; and, as I may so say, his first Will; from which we are not to recede, but upon clear evidence and necessity. And as in matter of Religion, we are to follow the known reveal'd Will of God, and not to trust to every impulse or motion of Enthusiasm, as coming from the Divine Spirit, unless there be evident marks that it is Supernatural, and cannot come from our own; So neither are we, without necessity, to quit the known and ordinary Will and Power of God … and fly to Supernatural Causes, or his extraordinary Will; for this is a kind of Enthusiasm or Fanaticism, as well as the other: And no doubt that great prodigality and waste of Miracles which some make, is no way to the honour of God or Religion.Footnote 53

This principle is adhered to throughout the Theory, and the Creation, Deluge, Conflagration and formation of the new Earth, are explained predominantly – though not entirely, as I shall discuss shortly – in terms of natural causes. Burnet was evidently aware that in presenting biblical events in this way he risked being perceived as having written providence out of sacred history. Especially problematic in this regard were events like the Deluge which were brought about as punishment for human sin, something that appeared difficult to square with their being the inevitable consequences of natural processes. To deal with this, he posited a divine synchronicity between the ‘natural’ or ‘material’ world on the one hand and the ‘moral’ or ‘intellectual’ world on the other. God, having foreseen human history, contrived a series of natural causes that will punish or reward humankind in accordance with its moral state. This, for Burnet, was more consistent with God's wisdom than the traditional picture of his observing sin and intervening in the world to punish it, for the course of nature

is a greater argument of wisdom and contrivance, than such a disposition of causes as will not in so good an order, or for so long a time produce regular effects, without an extraordinary concourse and interposition of the First cause … and that even in its greatest changes and revolutions it should still conspire and be prepar'd to answer the ends and purposes of the Divine Will in reference to the Moral World. This seems to me to be the great Art of Divine Providence, so to adjust the two Worlds, Humane and Natural, Material and Intellectual, as seeing thorough [sic] the possibilities and futuritions of each, according to the first state and circumstances he puts them under, they should all along correspond and fit one another, and especially in their great Crises and Periods.Footnote 54

Burnet's emphasis here on God's wisdom in employing natural causes strongly evinces the first of the two approaches to natural theology discussed in the introduction. This approach Mandelbrote associates principally with John Wilkins – one of the prominent Latitudinarians listed above – and Robert Boyle (1627–91), who appealed to law-like regularities in nature as evidence of the existence and attributes of God.Footnote 55 It is important to note here that Burnet departs to some extent from the traditional notion of natural theology as concerned with theological conclusions drawn from natural reason and independently of revelation in that he is inquiring into revealed doctrines.Footnote 56 His reasoning also differs in that, rather than arguing straightforwardly from order in nature to the wisdom of God, he takes God's wisdom as his point of departure, as something which entails that God must use natural means if such means are available and which implies that we must consider natural processes before appealing to extraordinary providence. The conclusion he draws, however, is essentially an extension of the design argument of Wilkins and Boyle. The fact that we can understand such events as the Creation, Deluge and Conflagration principally in terms of natural processes without having recourse to extraordinary providence constitutes compelling evidence that God does indeed possess this attribute, for he has contrived the world such that even these pivotal events in biblical history occur primarily according to the laws of nature and do not require his direct intervention.

Anti-voluntarism and angelic versus direct providence

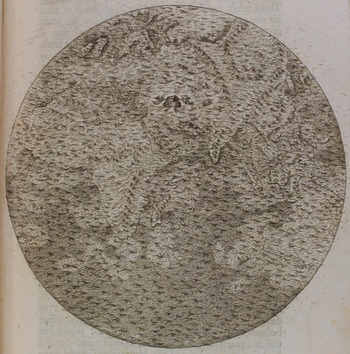

Despite his emphasis on natural over extraordinary providence, Burnet did not want to rule out miracles altogether. For while he emphasized God's wisdom over his will, he did not want the latter ‘so to be bound up to second causes, as never to use, upon occasion, an extraordinary influence or direction’.Footnote 57 Indeed, he saw an outright denial of miracles as more problematic than having too ready appeal to them, ‘for to deny all Miracles, is in effect to deny all reveal'd Religion’. He wanted, then, to allow some miraculous intervention, ‘so as neither to make the Divine Power too mean and cheap, nor the Power of Nature illimited and all-sufficient’.Footnote 58 He also maintained that miracles were involved in the Creation and Deluge, and that they will play a role in the Conflagration. The causal role of miracles in the Creation and Deluge in Burnet's account is somewhat vague, and I shall return to it shortly as the much clearer picture he gives of another miraculous element of the Deluge and of the miracles involved in the Conflagration will help shed light on it. This other miraculous element of the Deluge pertains to the protection of the ark. The violence of the waters, Burnet suggested, necessitated ‘an extraordinary and miraculous Providence’ to prevent the ark from being destroyed. To this end, he conjectured that it was protected by angels, a scenario he famously illustrated with an engraving of a submerged globe with the ark just above the centre flanked by two angels (Figures 1, 2).Footnote 59

Figure 1. Illustration of a submerged Earth with the ark above the centre flanked by angels. Thomas Burnet, The Theory of the Earth: Containing an Account of the Original of the Earth, and of all the General Changes which it hath Already Undergone, or is to Undergo till the Consummation of All Things, vol. 1, London, 1684, p. 101. Reproduced by permission of Durham University Library and Collections, Special Collections, SB+ 0480.

Figure 2. Close-up of the ark. Burnet, op. cit., p. 101. Reproduced by permission of Durham University Library and Collections, Special Collections, SB+ 0480.

Like the protection of the ark, the role of miracles in Burnet's account of the Conflagration also consists in the ministry of angels. Here, though, their role is very different in that they are involved in actually bringing the event about. It is here that Burnet first introduced his distinction between two kinds of miracle: ‘God's immediate Omnipotency’, and ‘the Ministry of Angels’. Both are to be considered miraculous, because both proceed from divine or supernatural rather than natural causes. Yet the distinction between them is significant, more significant even than that between the natural and the miraculous, because the difference between an angelic and an omnipotent power is far greater than that between the natural and the angelic. Here Burnet introduced a new component of his anti-voluntarism: where God can bring about his will via the ministry of angels, he will not intervene directly in the world. Here again, this rule by which God is bound proceeds from his wisdom, to which it is contrary for him to employ an omnipotent power where an angelic power is sufficient.Footnote 60

Assessing the powers of angels, Burnet noted in the first place that they are endowed with a perfect understanding of nature. They are able, therefore, to intervene in the natural world in ways that are not only above our capacities but beyond even our imagination. Additionally, where our souls can control only the motions of ‘spirits’ within our bodies, theirs can manipulate external nature.Footnote 61 Thus their dominion and power over the natural world far exceed ours, and hence nature is much more subject to their control than to our own. ‘From these considerations’, he observed, ‘it is reasonable to conclude, that the generality of miracles may be and are perform'd by Angels; It being less decorous to employ a Sovereign power, where a subaltern is sufficient’. From this, he derived a second methodological principle which is exactly analogous to the first. Just as we are not to appeal to miracles where natural causes are sufficient to explain a given event, so too we are not to appeal to God's direct intervention where the ministry of angels is sufficient. ‘[T]he reason in both Rules’, he emphasized, ‘is the same, namely, because it argues a defect of Wisdom in all Oeconomies to employ more and greater means than are sufficient’.Footnote 62

Burnet now applied this rule to the Conflagration. Drawing on a range of biblical illustrations of the propensities and capacities of angels, he noted in the first place that the notion of ‘Destroying Angels’ as ‘Executioners of the Divine Justice and Vengeance’ is well precedented, there being frequent instances in sacred history of God's judgement being dispensed by an angelic hand. As to their capacity to intervene in nature, it was evident that, among other things, angels can order and coordinate the natural causes that are to bring the Conflagration about, intensify the power of the sun, adjust the temperature of flames and alter the composition of bodies to make them more combustible. Natural causes, then, assisted by angelic intervention, are sufficient to burn the Earth. God's direct intervention could therefore be ruled out, since his wisdom prevents him from intervening directly in nature if his will can be effected via the ministry of angels. As with his defence of natural causes, Burnet was keen to emphasize the providential nature of angelic intervention and did so in markedly anti-voluntarist terms. It is no ‘diminution of Providence’, he wrote, ‘to put things into the hands of Angels; ’Tis the true rule and method of it; For to employ an Almighty power where it is not necessary, is to debase it, and give it a task fit for lower Beings’.Footnote 63 It is worth highlighting here that the phrase ‘rule and method’ is distinctly Cudworthian in that Cudworth used precisely these words when discussing providence in his True Intellectual System.Footnote 64

Turning now to the causal role of miracles in the Creation and Deluge, this, as I have noted, is rather vague in the first volume of the Theory. Following his explication of the Earth's formation, Burnet assessed that ‘we have propos'd the Natural Causes of it, and I do not know wherein our Explication is false or defective’, yet immediately afterwards described the structure of the primitive Earth as ‘so marvellous, that it ought rather to be consider'd as a particular effect of the Divine Art, than as the work of Nature’. He then quoted several biblical passages and other ancient writings which indicate that other, non-physical powers were involved in this ‘piece of Divine Geometry or Architecture’, but did not discuss what these powers might have been.Footnote 65 Later in the book when discussing the Deluge, he asserted that as ‘there was an extraordinary Providence in the formation or composition of the first Earth, so I believe there was also in the dissolution of it’, yet again said nothing about what this extraordinary providence may have consisted in in either case.Footnote 66

Things become clearer if we look at Burnet's two responses to Erasmus Warren (d. 1718), the rector of Worlington who entered into a hostile debate with Burnet after attacking the first volume of the Theory in his Geologia, or, a Discourse concerning the Earth Before the Deluge (1690). Warren had objected to Burnet's account of the Creation on the ground that the Earth's formation according to his theory would take far longer than the six days allotted by Moses.Footnote 67 Responding to this, Burnet suggested that the Earth's formation may be understood in terms of either ordinary or extraordinary providence. If the former, then it would obviously take longer than six days. If the latter, then the process may be expedited to occur in a shorter time frame.Footnote 68 This, however, was clearly not his actual position. To begin with, he explicitly stated that the proposal was merely a possible ‘general Answer’ to the objection.Footnote 69 We know, moreover, that he thought the Creation did take longer than six days, and that the Mosaic history was not to be understood literally. He had stated this in 1680/1 in correspondence with Isaac Newton (1643–1727) and made his first public statement of it in the Review of the Theory of the Earth, a supplement to the Theory published the same year as this first reply to Warren.Footnote 70 This position was intimated toward the end of the latter, too, for here he expressed his intention to produce an account of the Hexameron, and declared that this account ‘might have spar'd much of the Excepter's [Warren's] pains’, since his objections were grounded in a ‘vulgar’ reading of Moses with which the theory was obviously inconsistent.Footnote 71 He returned to this point in his second reply. Here, though, he was more explicit, stating that ‘the Theorist hath no where asserted, that Moses’s Cosmopoeia … is to be literally understood; and therefore what is urg'd against him from the letter of that Cosmopoeia, is improperly urg'd and without ground’.Footnote 72

Burnet's notion of speeding up the Earth's formation, then, was clearly not his view of the role of extraordinary providence in the Creation. His actual view of this, and of the miracles involved in the Deluge, becomes apparent in his second reply to Warren. In his first reply, Burnet had made other appeals to extraordinary providence when answering Warren's objections.Footnote 73 In his subsequent reply to Burnet, Warren took exception to this, and to Burnet's appeals to miracles in the Theory. First, he alleged, Burnet had violated his own principles, for he had insisted on explaining the Creation and Deluge in terms of natural causes but had nevertheless appealed to extraordinary providence and was appealing to it again to deal with objections. Second, by appealing to extraordinary providence, Burnet had rendered his theory superfluous. One of his key motivations was to explain the Deluge without invoking a miraculous creation and annihilation of water. By appealing to miracles himself, he had thereby rendered his theory no better than the traditional, miraculous interpretation of the event.Footnote 74 ‘To what purpose’, asked Warren, ‘did he [Burnet] invent a Theory, and write a Treatise with design to shut out one Extraordinary Providence, the creating of new Waters to make the Deluge; when in this Treatise, and to uphold that Theory, he is constrain'd to let in thus many?’Footnote 75

It is in his response to these points that Burnet's view of the miracles involved in the Creation and Deluge becomes clearer, for here he rebuked Warren for being ‘so injudicious … as to confound all extraordinary Providence with the Acts of Omnipotency’. It was such acts, he explained, and not miracles more generally, that he did not allow in his theory. ‘The Creation and Annihilation of waters … is an act of pure Omnipotency’. This, therefore, ‘The Theorist did not admit of at the Deluge: and if this be his fault, as it is frequently objected to him he perseveres in it still’. Here, as in his discussion of the Conflagration, he contrasted such ‘Acts of Omnipotency’ with the ministry of angels. ‘[A]s for acts of Angelical power’, he wrote,

he [the Theorist] does every where acknowledge them in the great Revolutions … of the natural World. If the Excepter [Warren] would make the Divine Omnipotency as cheap as the ministery of Angels, and have recourse as freely and as frequently to that, as to this: If he would make all extraordinary Providence the same … and set all at the pitch of Infinite power, this may be an effect of his ignorance or inadvertency, but is no way imputable to the Theorist.Footnote 76

Burnet's appeals to miracles, then, were to lesser miracles, those which can be effected by the ministry of angels and which do not require God's direct omnipotence. Thus he did not violate his principles or render his theory superfluous as Warren had claimed, for Warren's argument proceeded from an erroneous conflation of these two very distinct kinds of miracle.

From the foregoing argument against Warren, his assertion ‘that the generality of miracles … are perform'd by Angels’, the prodigious power over nature with which he believed angels are endowed, and his clear antipathy to the idea of God intervening directly in the world, it seems clear that the miracles Burnet envisaged as being involved in the formation and dissolution of the Earth at the Creation and Deluge, like those involved in the Conflagration, consisted in the ministry of angels. If this is correct, then in both volumes of the Theory, Burnet's anti-voluntarism underpinned not only his insistence on natural causes as the primary instruments of the divine will but also his views about the kinds of miracle that do, on occasion, occur. God's direct intervention is theoretically possible, but in virtually every conceivable case, God, in accordance with his wisdom, performs miracles not directly but via the medium of angels. Interestingly, this view of extraordinary providence can also be traced to Glanvill, for Glanvill, too, had allowed that on occasions where natural providence falls short, and where a phenomenon cannot be explained in terms of natural processes, ‘we may have recourse to the Arbitrary managements of those invisible Ministers of Equity and Justice, which without doubt the world is plentifully stored with’. Here, again anticipating Burnet, he pointed to scriptural evidence of angelic interventions in nature to support his contention.Footnote 77

Burnet's appeals to angelic providence occupy the other side of Mandelbrote's divide in seventeenth-century natural theology which emphasized – and sought to evidence – the role of spirits in the natural world. That we find such appeals in Burnet is unsurprising given that some of the Platonists and Latitudinarians discussed above, namely Cudworth, More and Glanvill, were the main proponents of this approach. All these authors gave spirits an indispensable role in nature, and More and Glanvill were among the most prominent investigators of spiritual phenomena in late seventeenth-century England.Footnote 78 The role of spirits in Burnet's world view was much less pervasive than it was for these authors, and his appeals to them were not as extensive or emphatic as his appeals to regular, law-like processes. Like his colleagues, he considered the human soul an immaterial substance of a divine or quasi-divine nature with the ability to effect changes in the material body through the exercise of free will.Footnote 79 He also, albeit very briefly in comparison, touched on subjects like witchcraft which had preoccupied More and Glanvill.Footnote 80 He appealed to both kinds of phenomena, moreover, as evidence for the existence and attributes of God.Footnote 81 As I noted above, however, where these authors incorporated such phenomena into a more general spiritualist framework, Burnet saw them essentially as aberrations in an otherwise mechanistic universe. Likewise, angelic interventions, unlike the all-encompassing spiritual principles of the Platonists, are employed only when God's ends cannot be achieved via purely mechanical means.

Conclusion

As I noted in the introduction, other historians have framed Burnet's commitment to natural over miraculous causes as an essentially Cartesian principle. Martin Rudwick, for example, argues that Burnet sought physical explanations for biblical events which could ‘satisfy the text of Scripture and other ancient records … and at the same time be framed within the Cartesian philosophy of nature, which permitted explanation only in terms of matter and motion’.Footnote 82 Poole contends that Burnet's promotion of ‘a model of general providence (“the laws of nature”) that would limit the need for the philosopher to appeal to special providence (“miracles”) … was a Cartesian move, as Descartes too had insisted on the necessity for God's general providence as the caretaker and conserver of Creation's regular movements’.Footnote 83 Many of Burnet's contemporaries interpreted him in this way, too. As Peter Harrison notes, the aspect of Cartesianism to which critics of Burnet objected most was not his use of Cartesian cosmology but what they viewed as ‘the Cartesian mode of explanation’; that is, the attempt ‘to describe all the features of the world in terms of secondary causes’.Footnote 84

If the above analysis is correct, however, the actual foundations of Burnet's commitment to natural over miraculous causes were in important respects distinctly un-Cartesian. The two authors’ views of providence were admittedly superficially similar in that both thought that the laws of nature are the ordinary will of God and that they are for the most part invariable. The theological foundations of their views, however, were substantially different. They also had quite different implications regarding the place of miracles in the providential order. First, as I have argued, Burnet's preference for natural over miraculous providence was underpinned by the anti-voluntarist idea that God is constrained to act in accordance with his wisdom. This is a significant departure from the Cartesian conception of God, for Descartes had espoused an especially radical form of theological voluntarism according to which the very nature of wisdom, goodness and even the laws of logic and mathematics proceed from God's completely free will.Footnote 85 Certainly this is how Descartes was generally interpreted by his contemporaries, and two of the most prominent figures to interpret him this way were Burnet's Platonist colleagues at Christ's, both of whom objected strenuously to this aspect of the Cartesian world view and positioned their anti-voluntarism against it.Footnote 86 More did so obliquely in his Divine Dialogues (1668) by having the Cartesian Cuphophron voice voluntaristic ideas and his own mouthpiece Philotheus repudiate them.Footnote 87 Cudworth did so directly, naming Descartes as his adversary and attacking his voluntarism both in the True Intellectual System and in his posthumously published work.Footnote 88 This foundation of Burnet's adherence to natural over miraculous causes, then, was directly opposed to this tenet of Descartes's philosophy and had been pitted expressly against him by some of the very people from whom Burnet inherited it.

Second, for Descartes, the laws of nature are the primary will of God and are invariable because God's will is immutable. Once God had freely chosen the laws of nature, they became his will, and they remain fixed because any change in them would imply an imperfection in God.Footnote 89 This, on the face of it, seems to rule out miracles, and Descartes said as much concerning his hypothetical world in the Treatise on Light – ‘God will never perform a miracle’.Footnote 90 Later, in the Principles of Philosophy, he acknowledged ‘those changes which … divine revelation renders certain, and which we … believe to occur without any change on the part of the Creator’ as exceptions to the laws of nature which are to be disregarded for the purposes of doing natural philosophy.Footnote 91 Yet it was unclear how these events might be brought about without violating God's immutability, and Descartes never addressed this. Burnet's view of providence, on the other hand, was underpinned by God's wisdom. That God works primarily via natural processes and that these processes are generally invariable are consequences of his possessing this attribute. Yet it is not inconsistent with this attribute for God to use the ministry of angels or even in principle to intervene directly in the world, for such actions are only contrary to God's wisdom if lesser means are available. By grounding providence in God's wisdom rather than his immutability, Burnet could fit miracles consistently into his world view in a way that was unavailable to Descartes.

Before closing, it is worth noting that Burnet's anti-voluntarism is evident in his other writings. It is prominent, as I mentioned above, in his controversial denial of the literal sense of the Mosaic history of the Creation and Fall in the Archaeologiae, for here he emphasized that the disproportionate assignment of tasks to days in the former contradicts God's wisdom, and the disproportionate punishment for Adam's sin in the latter contradicts his goodness. God cannot have conducted himself in these ways, and so the literal sense of these texts must be abandoned.Footnote 92 A similar argument appears in a posthumously published work on the state of the dead and the Resurrection that is to follow the Conflagration. Here, he discussed at length the torments of hell, arguing that they cannot be eternal because God's wisdom and goodness prevent him from inflicting eternal punishment on his creatures, and so the common, literal interpretation of Scripture on this point should be rejected too.Footnote 93 This emphasis on God's attributes and the restrictions they impose on his will, then, is a recurring theme in Burnet's work and one which underpinned many of his views on both nature and Scripture. This, rather than his Cartesianism, was the primary basis of his commitment to natural over miraculous causes and of his parallel commitment to angelic over direct providence.

Rather than someone who simply applied the Cartesian principle of explaining events in terms of natural causes, Burnet emerges from this analysis as a more complex, consistent and principled thinker. Burnet was not merely applying Cartesian natural philosophy to biblical history. Like other English thinkers, he adopted significant tenets of the Cartesian system but eschewed others. And the principles he did adopt were combined with others derived from elsewhere – some of which were directly opposed to those of Descartes and based on markedly different foundations with very different implications – to construct a theory of the Earth based on both Cartesian natural philosophy and the rational theology of the Cambridge Platonists and Latitudinarians. Had his use of natural causes been derived primarily from this Cartesian principle, then he could have been accused of applying the principle inconsistently, for he did include miracles in his theory. If, on the other hand, he prioritized both natural causes over miracles and angelic intervention over acts of omnipotence because God's attributes impose constraints on how he can execute his will, then he was applying a quite different principle and doing so consistently. The Cartesian interpretation also makes him more vulnerable to Warren's criticism, for without a principled reason for appealing to miracles, the claim that he was doing so in an ad hoc manner to supply the defects of his theory would have had more force, and his appeal to the distinction between angelic and direct providence in answering this criticism would have seemed equally ad hoc.

This analysis also vindicates to some extent Gascoigne's and Olsen's characterization of the Theory as a work of Latitudinarian theology and natural philosophy, for in addition to the various other recognizably Latitudinarian doctrines at work in the book, Burnet's anti-voluntarism played a key role in shaping his view of both ordinary and extraordinary providence. The work also combines two distinct kinds of natural theology that were promoted by Latitudinarians. Whether this qualifies him as ‘a Latitudinarian divine’ is another question. Intellectually, there is little doubt that many aspects of Burnet's work were closely aligned with Latitudinarian thinking. Socially, on the other hand, apart from his close relationship with Tillotson, he seems to have been outside the Latitudinarians’ inner circle. This, however, was not so much because he did not share their principles, but rather because he took these principles to conclusions that few Latitudinarians were willing to entertain.

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship at the Sidney M. Edelstein Center for the History and Philosophy of Science, Technology and Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I am grateful to the Center for supporting my work and to members of the Center for their questions and comments on a presentation of the article. The article also expands on ideas from my PhD, during which I benefited from discussions of the topic with my supervisors Peter Vickers and Matthew Eddy, and examiners Catherine Wilson and Robin Hendry. I would also like to thank participants at the British Society for the History of Science annual conference 2022 for their helpful input; Amanda Rees and two anonymous reviewers, whose insightful comments and suggestions have greatly improved the paper; Trish Hatton for her friendly and efficient communication; and Durham University Library for granting permission to use images from their Special Collections.