1. Introduction

Secure psychiatric hospitals, dually tasked with treating forensic psychiatric patients and ensuring public safety, represent a high-cost and low-volume service [Reference Skipworth, Brinded, Chaplow and Frampton1]. Conditionally discharged forensic patients are those who have progressed through forensic inpatient services and been deemed safe to live in the community. Patients are released from secure care on the basis they adhere to specific discharge conditions and formal readmission to a secure hospital (herein referred to as recall) can be enforced should the patient not adhere to these conditions.

Re-hospitalisation is not a desirable outcome for patients following discharge and secure hospital care is expensive. In the United Kingdom (UK) the annual cost of a medium secure bed is in the region of £165, 000 and a high security inpatient bed is £300, 000 [2]. Forensic inpatient admissions are typically longer than acute psychiatric admissions, with a low turnover rate. In Australia, mentally ill homicide offenders have a mean length of stay of six years in secure care [Reference Ong, Carroll, Reid and Deacon3], whilst in New Zealand, insanity acquittees have an initial average length of admission of five years [Reference Skipworth, Brinded, Chaplow and Frampton1]. In light of the cost and length of admission, the sustainability of secure forensic services has been brought into question [Reference Wilson, James and Forrester4]. To justify such an expensive and undesirable intervention, research has sought to better understand the outcomes for forensic psychiatric patients released from secure care in order to improve patients’ recovery and well-being as well as justify this high cost intervention.

Outcome studies of patients admitted to secure hospitals have focused predominantly on reconviction rates [Reference Jamieson and Taylor5]. Where readmission to psychiatric hospitals has been assessed, rates are high [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6]. The National Cohort Study in England and Wales followed patients for an average of 6.6 years (range six months-14 years) and found that 75% of forensic patients required at least one readmission following discharge from medium secure care [Reference Maden, Rutter, McClintock, Friendship and Gunn7]. Similarly, a twenty-year follow-up study of forensic patients discharged from medium secure units in the UK observed that 69% were subsequently readmitted to hospital [Reference Davies, Clarke, Hollin and Duggan8]. Comparable rates have been observed outside of the UK, with one Canadian study reporting that 55% of the studied sample were returned to hospital within a year of follow-up [Reference Melnychuk, Verdun-Jones and Brink9] and a New Zealand study reporting that one third of forensic patients were readmitted within two years of discharge, increasing to 80% readmitted within 15 years [Reference Skipworth, Brinded, Chaplow and Frampton1].

A recall can take place if a conditionally discharged patient is showing signs of deterioration or if they fail to comply with the conditions of their discharge. The recall represents a type of readmission which requires the formal authorisation of a governing body; in the UK this is the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), who legally direct the recalled patient to a psychiatric hospital. Data on the rates of recall compared with standard readmission (i.e., a readmission not requiring formal authorisation from the MoJ) are limited, but there is some indication that recall rates for forensic patients are relatively high. Rates ranging from 12–17% after two years [Reference Davies10] to 35% over a 20-year follow-up period [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6] have previously been reported in the UK; compared to a 19% recall rate for conditionally released patients in New Zealand [Reference Simpson, Jones, Evans and McKenna11]. Recall versus readmission practices vary by locality and over time. In the UK, for example, an offence committed by a readmitted forensic patient who was offered leave led to a practice change, such that all readmitted forensic patients are now subject to formal recall [12].

Little is known about predictors of readmission or recall for forensic patients. Previous research in Canada, the UK, New Zealand, and Norway has observed that readmission rates are higher among males, younger individuals, those with a history of repeated psychiatric admission, a classification of mental illness (when compared to psychopathic disorder), a history of self-harm, and a history of substance abuse [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6, Reference Salem, Crocker, Charette, Seto, Nicholls and Côté13–Reference Akande, Beer and Ratnajothy16]. However, several previous studies found no significant predictors of readmission or recall [Reference Maden, Rutter, McClintock, Friendship and Gunn7, Reference Davies10], or did not specifically examine factors associated with these outcomes [Reference Skipworth, Brinded, Chaplow and Frampton1, Reference Davies, Clarke, Hollin and Duggan8, Reference Akande, Beer and Ratnajothy17]. Furthermore, previous research rarely examines factors associated with recall specifically.

The current study aims to examine the rates of recall for a cohort of conditionally discharged forensic patients and to assess the reasons attributed to the recall. Due to the paucity of research examining predictors of recall, the current study aimed to conduct an exploratory investigation to determine possible predictors. In addition to variables identified in the literature (i.e. substance abuse, history of psychiatric admissions, and age), demographic, clinical, and forensic variables which are readily available to treatment teams via a patients’ medical record were chosen for inclusion in the study.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and setting

The sample consisted of forensic psychiatric patients conditionally discharged under a section 37/41 restriction order from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) forensic inpatient services. SLaM is one of Europe’s largest providers of secondary mental health care, providing care predominately for the London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark, Croydon, and Lewisham [Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta18]. The definition of a forensic patient differs across jurisdictions. In this paper, a forensic patient is defined as an offender who is suffering from a mental illness, and has been detained and treated under a section 37/41 restriction order. In the UK, a section 37, also termed a hospital order, is a court order imposed instead of a prison sentence in circumstances where, at the time of sentencing, the offender is found to be sufficiently mentally unwell to require hospitalisation. The section 41 restriction order is made in addition to the section 37. The restriction order affects leave of absence, transfer between hospitals, and discharge, all of which require MoJ approval [19].

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected using the Clinical Records Interactive Search (CRIS) system, an anonymised database of electronic medical records. The CRIS system, described previously in detail [Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta18, Reference Stewart, Soremekun, Perera, Broadbent, Callard and Denis20, Reference Fernandes, Cloete, Broadbent, Hayes, Chang and Jackson21], provides authorised researchers with secure and regulated access to anonymised records for over 250, 000 mental health service users within the SLaM Trust [Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta18]. CRIS enables researchers to extract data from the structured and unstructured fields of the record. Baseline exposure data were collected retrospectively via CRIS and included demographic, clinical, and forensic factors (Table 1). Free text searching was used to identify relevant documents and variables were manually coded.

2.3. Outcome data

The study period extended for 6.25 years from January 2007 to April 2013. The starting point for the time period was determined by the availability of data held in the CRIS system. The data collection census date was 30th June 2013; allowing a minimum three-month follow-up. The primary outcome measure was formal readmission to secure care. In the UK, this is termed a “recall” to hospital authorised by the MoJ under section 37/41 of The Mental Health Act (1983) (MHA). Readmission to hospital in any other form, general or psychiatric, was not included.

The initial search identified 219 patients that had been placed under a section 37/41 restriction order. After individually screening each case, we excluded those discharged prior to 2007 or after April 2013, and those not conditionally discharged during the study period (n = 104). Cases were also excluded if the individual was no longer a SLaM patient due to being transferred to another healthcare provider or prison (n = 13), as we could not determine outcomes for these patients. Unconditionally discharged patients were excluded as they were no longer subject to the section 41 restriction order and hence not at risk of recall (n = 1). Individuals who were unconditionally discharged after a period of conditional discharge were censored at the point that the conditions were removed. The final sample consisted of all patients conditionally discharged, under a section 37/41 restriction order, within SLaM forensic inpatient services, between January 2007 and April 2013 (N = 101). Only data on the first recall of each patient within the follow-up period were included in statistical analyses.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using SPSS version 21. Time to recall for the total sample was examined using Kaplan-Meier survival analyses. Recalls were compared within the context of demographic, clinical, and forensic predictors using univariable Cox regression [Reference Altman22]. Cox regression was then used to construct a multifactorial prediction model of recall using significant predictors from the univariable analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to determine mean time to recall for individual predictors in post-hoc analyses. For the purposes of the survival analysis, all independent variables used were fixed time invariant including historical items on HCR-20 assessments.

Table 1 Examined predictors of recall.

2.5. Ethics

CRIS was approved as a dataset for secondary analysis by the Oxford Research Ethics Committee C (08/H0606/71). Approval to conduct the study was granted in May 2013 by the CRIS Oversight Committee.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The study sample (N = 101) was predominantly male (82.2%) and of non-white ethnicity (71.3%), with a mean age at the point of conditional discharge of 40 years (median 38; range 21–84). The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 90 (89.1%) patients had a diagnosed psychotic illness. Personality disorder (primary or comorbid diagnosis) was diagnosed in 39.6% of the sample. Nearly three-quarters of the sample met criteria for substance use disorder (72.3%), with high rates of cannabis (61.4%), alcohol (42.6%), and stimulant (39.6%) abuse recorded. The mean length of time spent under a forensic hospital order at the point of discharge was 7.8 years for men (median 5.1; range 0.6–33.8; SD = 6.9) and 7.1 years for women (median 5.3; range 0.4–22.6; SD = 6.5).

3.2. Overview of recall

Of the 101 patients conditionally discharged from SLaM forensic services, 45 (44.5%) were recalled to hospital during the follow-up period (mean follow-up time 811 days; range 25–2246). Eight patients were recalled twice or more and two patients were recalled three or more times. The average time to recall decreased with consecutive periods of readmission; with the average time to the first, second, and third recall being 500 days (median 395; range 26–1970), 212 days (median 162; range 14–576), and 77 days (median 77; range 39–115), respectively.

The most common reason for initiating a recall was concern regarding deterioration in a patient’s mental state (86%), followed by substance misuse and non-compliance with medication (both identified in 58% of cases). Threatening behavior and violence were cited as the reason for recall in 51% and 23% of cases, respectively. Actual conviction occurred in just 1% of first recall cases.

3.3. Univariable predictors of recall

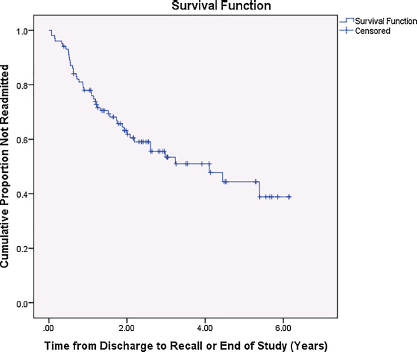

Time to first recall was examined using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with cases censored if patients were not recalled, had died, or were lost to follow-up in the observation period; Fig. 1 depicts the average survival curve for the full sample. The cumulative proportion surviving recall by the end of the study was 0.39.

Results of a Cox regression analysis examining the association between demographic factors and recall (Table 2) indicated that the time to first recall was significantly shorter for patients who were aged ≤ 38 years at the point of conditional discharge compared to those who were aged >38 years (HR 1.89; 95% CI 1.02–3.49; p = 0.04) and that those who were of non-white ethnicities (i.e. Caribbean, African, and other) were over three times more likely to be recalled than those of white British ethnicity (HR 3.44; 95% CI 1.45–8.13; p = 0.005).

With regards to clinical variables (Table 2), being known to mental health services prior to the index admission (HR 3.44; 95% CI 1.06–11.16; p = 0.04) and a past psychiatric admission (HR 2.44; 95% CI 1.08–5.52; p = 0.03) were significantly associated with earlier recall. Patients with a substance abuse disorder (HR 2.52; 95% CI 1.17–5.43; p = 0.02), specifically cannabis (HR 2.18; 95% CI 1.14 –4.19; p = 0.02) and/or stimulant abuse (HR 2.06; 95% CI 1.15–3.71; p = 0.02), had a shorter time to recall. Patients on depot antipsychotics were over two times more likely to be recalled than people not on a depot antipsychotic (HR 2.17; 95% CI 1.14–4.11; p = 0.02). In contrast, patients treated with clozapine survived longer following discharge, compared to those individuals who were not treated with clozapine (HR 0.40; 95% CI 0.20–0.79; p = 0.009).

Of the forensic variables examined (Table 2), time to first recall was significantly shorter for patients who scored positively on H2: young age at first violent incident (HR 1.90; 95% CI 1.03–3.50; p = 0.04) and H8: early maladjustment (HR 1.92; 95% CI 1.01-3.68; p = 0.05) of the historical subscale of the HCR-20 violence risk assessment.

Fig. 1 Average survival curve for the full sample (n = 101).

Table 2 Cox regression survival analysis examining demographic, clinical, and forensic predictors of recall.

a Compared to age > 38.

b Compared to individuals of white ethnicity.

3.4. Multivariable analysis

Cox regression was used to construct a multifactorial prediction model of recall. Significant univariable predictors of time-to-recall (p < 0.05) were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Given the high rates of polysubstance abuse in the sample, only a substance use disorder diagnosis was included in the model. The model (Table 3) was constructed in a forward step-wise fashion. Initially, demographic variables were entered into the model (i.e., age ≤ 38 and non-white ethnicity), followed by clinical variables (i.e., depot medication, substance abuse, and clozapine), variables relating to service use (i.e., known to mental health services prior to index admission and previous psychiatric admissions), and historical forensic variables (i.e., early maladjustment and early violence). Clozapine treatment was not significant when added to the model in the second step, potentially due to a negative confounding effect of another predictor, however, once the model was adjusted for variables relating to service use and historical forensic variables this became significant. Ethnicity remained significant throughout each step of the model. Three factors remained significant independent predictors of time to recall in the final model; non-white ethnicity, early maladjustment, and clozapine treatment. Non-white ethnicity (HR 3.06; 95% CI 1.20–7.79; p = 0.02), early childhood maladjustment (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.05–4.73; p = 0.04), and not being treated with clozapine (HR 2.66; 95% CI 1.22–5.78; p = 0.01) were all associated with over a two-fold increase in recall risk during the follow-up period. After adjusting for the time spent on section 37/41 prior to conditional discharge in the multivariable model results remained largely the same, with non-white ethnicity, early childhood maladjustment, and clozapine treatment remaining significant independent predictors of time to recall.

3.5. Post-hoc analysis

We adjusted the multivariable model for a number of forensic variables which may have had an overall effect on the prediction of the model. After adjusting for personality disorder, prior supervision failure, index offence, and past forensic history, results were largely unchanged, however, the effect of H8: early childhood maladjustment was reduced to trend level significance despite virtually no change in the hazard ratio (HR 2.11; 95% CI 0.90–4.94; p = 0.09).

We examined the significant independent predictors of time to recall further in post-hoc Kaplan-Meier survival analyses (Fig. 2). Forensic patients treated with clozapine (Panel A), of white ethnicity (Panel B), and who did not experience early childhood maladjustment (Panel C) survived longer following conditional discharge. The mean time to recall for patients on clozapine was 4.44 years (95% CI = 3.74, 5.14) compared to 3.08 years (95% CI = 2.41, 3.74) for individuals not on clozapine, patients of white ethnicity survived an average of 4.65 years (95% CI = 3.46, 5.00) vs. 3.09 years (95% CI = 3.46, 5.00) for patients of non-white ethnicity, and individuals who did not experience early childhood maladjustment survived an average of 4.23 years (95% CI = 3.46, 5.00) compared to 3.30 years (95% CI = 2.62, 3.98) for patients who had experienced early childhood maladjustment.

4. Discussion

This is the first study in the UK to examine a range of predictors of recall, which are readily available to clinical teams, in a sample of conditionally discharged forensic inpatients. Within this sample of 101 patients, just under half were (44.5%) were recalled to hospital on at least one occasion. The most common reason for recall was concern regarding mental state deterioration. Younger age (≤ 38), non-white ethnicity, a history of substance abuse (specifically cannabis and stimulant abuse), being known to mental health services prior to the index admission, past psychiatric admissions, depot treatment, and a score of definitely present on HCR-20 historical subscale items: young age at first violence and early childhood maladjustment, were all associated with a significantly shorter time to recall. Treatment with clozapine was associated with significantly longer time to recall. Multivariable analysis indicated that non-white ethnicity, early childhood maladjustment, and clozapine treatment were all significant independent predictors of time to recall. The average time to recall decreased with consecutive periods of readmission; this is consistent with previous research into returns to hospital in a Canadian sample of forensic patients [Reference Melnychuk, Verdun-Jones and Brink9].

The rate of recall observed in the current study (45%) is higher than rates observed in previous UK and New Zealand studies (12–35%) [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6, Reference Davies10, Reference Simpson, Jones, Evans and McKenna11], which may be due to differences in the length of follow-up, variations in recall versus readmission practices across study settings, and changes in thresholds for readmission/recall over time and across jurisdictions. Re-hospitalisation does not necessarily reflect treatment failure; it can be argued that a low threshold for recall is justifiable in this population; giving patients the chance to demonstrate their ability to manage community living whilst providing public reassurance. Forensic patients may also require high rates of recall as a means of managing their risk of re-offending. In the current study offending occurred as a trigger for recall in a small number of cases (1%).

Little is known about predictors of recall; previous research has focused on readmission rates and the factors associated with readmission. Although readmission can include recall, it is not clear whether these findings translate to conditionally discharged patients who are recalled to hospital. Contrary to research into predictors of readmission [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6, Reference Maden, Rutter, McClintock, Friendship and Gunn7, Reference Salem, Crocker, Charette, Seto, Nicholls and Côté13, Reference Hayes, Kemp, Large and Nielssen15]; a novel finding was the association between ethnicity and recall. We found that patients of non-white ethnicity were more likely to be recalled to hospital and that ethnicity remained a significant predictor after adjustment for other factors. Although, this finding might reflect the demography of the current sample and may not be generalisable. Those of non-white ethnicity in our sample may have been more likely to have a range of unmeasured or inadequately measured confounding factors that increased their likelihood of recall. Consistent with previous research [Reference Salem, Crocker, Charette, Seto, Nicholls and Côté13, Reference Hayes, Kemp, Large and Nielssen15] we found that younger patients, aged less than 38, were more likely to be recalled to hospital.

Table 3 Forward stepwise multivariable cox regression analysis examining significant univariable predictors of recall.

Fig. 2 Kaplan-Meir survival curves of significant independent predictors of time to recall.

In line with research into readmission predictors, being known to mental health services and a history of psychiatric admission prior to the index admission were associated with an early recall [Reference Clarke, Duggan, Hollin, Huband, McCarthy and Davies6], perhaps an indicator of illness severity or the presence of other risk factors associated with poor outcomes. However, contrary to previous findings, we found that a substance abuse diagnosis was associated with early recall, specifically, cannabis and stimulant use were significantly associated with a shorter time to recall. This fits with our finding that substance misuse was the second most common reason for recall. It is unsurprising that individuals with a history of substance misuse experience shorter time to recall as the association between substance abuse, crime, and violence is long established [Reference Pickard and Fazel23, Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann24]. Although, it is important to note that only a small number of recalls in the current study were due to violence or crime (23% and 1% respectively), and substance misuse can also be related to the symptomatology of specific mental disorders.

Within the current study, patients who were prescribed a depot antipsychotic when discharged had a significantly shorter time to recall. The association between depot prescription and rate of recall could reflect the likelihood that individuals prescribed depot medication may have histories of poor treatment adherence, this, and other risks related to non-adherence, such as poor insight, may be driving the relationship between depot medication and recall. We would not therefore recommend that due to the risk of recall patients should not be prescribed depot antipsychotics, however, it is important that treating teams are aware of the increased risk of recall for individuals on depot antipsychotics so that these patients can be closely monitored.

Patients who were receiving clozapine had a significantly longer time to recall. Clozapine treatment also remained a significant predictor of time to recall in the final multivariable model after adjusting for other variables relating to service use, clinical factors, historical forensic variables, and demographic factors, indicating that clozapine treatment independently predicted recall. Previous randomised control trials have found that clozapine has an anti-aggressive effect in psychiatric patients [Reference Krakowski, Czobor, Citrome, Bark and Cooper25, Reference Frogley, Taylor, Dickens and Picchioni26]. Within our sample, violent behavior was noted by clinical teams to be a contributing factor in 23% of first recalls; the reduction in aggressive behavior in patients prescribed clozapine may have acted as a protective factor, although further work would be required to establish this. It is also possible that patients prescribed clozapine were more mentally stable, given the superior efficacy of clozapine in treatment-refractory schizophrenia, and/or they were more compliant with treatment, since treatment with clozapine requires reliable compliance with oral medication and regular blood testing.

After examining individual historical subscale items of the HCR-20, assessing historical, criminogenic factors, we found that the presence of H2: young age at first violent incident and H8: early maladjustment were significantly associated with a shorter time to recall. These findings contrast with those of a study in New Zealand where no association between H score and readmission were found [Reference Simpson, Jones, Evans and McKenna11], although this again may reflect differences in predictors of readmission versus recall. A novel finding from our study is that early childhood maladjustment also remained a significant predictor of time to recall in the final multivariable model indicating that it independently predicted recall. Early childhood maladjustment is a historical risk factor which reflects a history of childhood trauma/victimisation and/or childhood conduct problems. Individuals with such histories have an increased risk of developing a range of mental health and behavioural problems later in life [Reference Bruce and Laporte27]. Although this is a static variable, the consequences of early childhood maladjustment may be reflected in adulthood in the form of personality problems which could be targeted by interventions which may in turn reduce the risk of recall in these individuals.

4.1. Implications

This study has important implications for conditionally discharged forensic patients and their treating teams. Recall to psychiatric hospital is an undesirable outcome which is both expensive and disruptive to patients’ care, and, as shown in the current study, relatively common among forensic psychiatric patients. Our findings indicate that several demographic and clinical factors are significantly associated with recall; by identifying these predictors, we can guide future research to determine if targeted interventions can modify the risk of recall in this group. For example, we found in the current study that substance misuse was the second most common reason for recall and that substance misuse was significantly associated with a shorter time to recall, therefore, treatment programs which focus on substance misuse may help to prevent future recalls. Furthermore, we found that patients treated with clozapine survived longer following discharge, compared to individuals not treated with clozapine. This effect persisted even after accounting for other factors; therefore, this may be an important treatment consideration for forensic patients. Although it is important for clinicians to take into account the side effects associated with clozapine, such as sedation and weight-gain [Reference Miller28], when considering it as a treatment option.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

The use of medical records for observational research has many advantages; the CRIS system allowed us to identify the total recalled population from one defined service, potentially minimizing selection and information biases. However, such investigations are reliant on the accuracy and completeness of the data within these records which may lead to misclassification of the exposure and/or outcome variables. The external validity of this approach is, however, likely to be high given that the CRIS system enabled us to search all available documents within the records, including free-text reports; thus, we could capture exposure variables which are routinely available to clinical teams. Readmission to hospital was not assessed, either prior to, or during the study period; any patient within the cohort who was readmitted to hospital, rather than formally recalled, was censored. Whilst it was not our intention to examine rates of readmission, we may have underestimated the recall rates of patients who were conditionally discharged following readmission and we were subsequently unable to examine the effect of past readmissions on recall.

The current study is limited by the single measures of potentially time-variant covariates; the association between these time-variant variables and recall may therefore have been attenuated. We have not, for example, considered any variables or changes in measured variables during the period between discharge and subsequent recall. Furthermore, some patients have only three months follow-up period giving less time for a recall to have occurred.

The small sample size of the current study may have precluded our ability to identify significant associations between exposure variables and recall for those potential predictors uncommonly present in our sample. Nonetheless, we identified several factors that significantly predicted recall. Previous research has found that individuals discharged to independent housing are significantly more likely to be readmitted to hospital when compared to individuals in supportive housing [Reference Salem, Crocker, Charette, Seto, Nicholls and Côté13]. Unfortunately, within the current study we were unable to examine factors outside of the ward environment, such as information on housing status, location of discharge, or social support, which may have had an influence on risk of recall.

Due to the small sample size and a large overlap in reasons for initiating a recall in the current study we were unable to explore the differences in predictors of criminal vs. clinical recalls, future studies should aim to increase the sample size in order to examine whether predictors of recall differ depending on the reason for the recall.

4.3. Conclusions

The current study aimed to conduct an exploratory investigation of predictors of recall for forensic patients. We found that age, ethnicity, substance abuse, being known to mental health services, past psychiatric admissions, depot treatment, and a score of definitely-present on H2: young age at first violence and H8: early childhood maladjustment of the historical subscale of the HCR-20, were all associated with a significantly shorter time to recall. In contrast, treatment with clozapine was associated with a significantly longer time to recall. Future research must now determine whether interventions specifically targeting these factors can modify the risk of recall for forensic patients.

Funding

This paper represents independent research part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. KD is funded by the Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network, New South Wales, Australia. CC was supported with fellowship funding from the New South Wales Institute of Psychiatry.

Disclosure of Interest

The authors have declared that no disclosures of interest exist.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff at the Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Nucleus for assistance with data extraction and continued support of the study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.