1. Introduction

Mr Zhang drowned in a fishpond on the property of the Huludao Jinhui Agricultural Industrial and Commercial Group Company, in Liaoning Province in China’s north-east. Zhang’s family sued, arguing that the company was negligent in failing to take adequate safety precautions. On appeal, the Huludao Intermediate Court rejected the family’s legal claim, finding that Zhang was mentally ill, and that there was no way that the company could have completely prevented the tragedy.Footnote 1 The court concluded that Zhang’s guardians had failed in their responsibility to supervise him and thus “to hold others responsible … has no legal basis.”

Nevertheless, the court proceeded to order the defendant company to pay 50,000 yuan in compensation to the family. “It cannot be denied that Zhang’s … accidental death has caused his family huge suffering and economic harm,” the court wrote. “In particular, the deceased has elders above and a minor child below, and they are deserving of sympathy.” The court’s anger at the defendant’s conduct was clear. The decision noted that the plaintiffs had accepted an initial settlement offer from the company arrived at through court mediation and expressed frustration that the company had added a new condition to its offer, insisting that the family transfer a piece of land in exchange for compensation. The court noted that the company’s decision to withdraw their offer was in accordance with “formal justice,” but was “out of step with substantive justice” and “would cause harm to the creation of a spirit of peace and order and public order and morals.”Footnote 2 The court concluded:

In light of the above, this court believes that although [defendant company] subjectively was without fault, nevertheless starting from the perspective of taking the people as the basis, our nation’s national circumstances, and positive village customs, giving some compensation in light of the circumstances will better reveal the substantive justice of law.Footnote 3

The Huludao court’s embrace of substantive justice and “the people as the basis”Footnote 4 as grounds for awarding compensation was not unusual for Chinese courts. In cases that involve bad luck, catastrophic loss, and even commonplace accidents, Chinese courts routinely ask defendants to pay damages without evidence of negligence. At times, courts make such arguments explicitly, as with the Huludao court. In others, courts use less direct terms, including “reason,” “discretion,” or “actual circumstances,” or cite legal provisions that allow courts to adjust outcomes based on equity.

In the English-language scholarship on Chinese courts, one consistent empirical finding is that litigants care more about how their case turns out than they do about whether the process was fair. In other words, they prioritize substantive justice over procedural justice.Footnote 5 It is also well documented that Chinese courts place great emphasis on results,Footnote 6 partly in response to litigants’ expectations and also partly reflecting a tradition of adapting law to community mores, especially in rural areas.Footnote 7 Chinese courts have a reputation for wanting to arrive at an outcome that all parties can live with, in particular in cases involving potential unrest, even when doing so requires stretching the law or even ignoring it altogether. In civil cases, this orientation toward satisfying litigants often leads Chinese courts to split the difference between the two sides, typically by awarding some fraction of compensation requested.Footnote 8

The pursuit of fairness and justice continues to be an explicit goal of the legal system under General Secretary Xi Jinping and the slogan “let the people feel justice in each case” hangs on the walls of many courtrooms.Footnote 9 But, of course, leaving court-users with a sense that justice has been done is no easy task. Beyond their well-known tendency to compromise, when and how do Chinese courts arrive at decisions that feel “fair and just”? Although a great deal of prior scholarship reveals that Chinese courts search out compromise, virtually none has explored the values implicit (and sometimes explicit) in these decisions. How do Chinese courts operationalize fairness and justice (公平公正) in published decisions that either directly use such language or reference closely related ideas and legal provisions? This is a question about China’s contemporary legal culture or the “relatively stable pattern of legally oriented social behavior and attitudes” that undergirds any legal system.Footnote 10 Building on a tradition of comparative law research that tries to unpack key hard-to-translate legal ideas in ways that reflect local understandings, we adopt an interpretive approach that examines what Chinese courts do in a database of 10,000 judicial decisions, mostly tort cases, that include language about fairness, or the need to take account of actual circumstances, or cite provisions of Chinese law that authorize courts to look beyond which party is at fault. We also read and coded at least 250 cases in three categories—injuries to students at school, child drownings, and death due to excessive alcohol consumption—to investigate whether the legal reasoning and outcomes we saw in the larger data set were also prevalent in a broader swath of similar cases that did not necessarily include the same direct references to fairness, equity, and discretion.Footnote 11

What we find is that Chinese courts try to smooth misfortune by imposing costs on parties with ethical, but not legal, obligations to the victims. The legal reasoning in these decisions reflects two de facto doctrines, or common judicial solutions to recurrent fact patterns, that assign liability to people linked through a relationship. We identify two types of relationship-based liability: participant liability, which assigns liability to those participating in a shared activity; and space-based liability, which assigns liability to those who control a physical space. Sometimes courts are acting within the broad discretion granted to them by Chinese law. Other times, as with the Huludao court above, Chinese courts stretch or ignore legal provisions to resolve disputes in ways that go beyond or violate the law as written. The theme is that judges share an impulse to assign legal responsibility to certain social relationships and to spread economic losses through a community. The damages imposed range from a de minimis acknowledgement of trauma in cases in which the victim was largely or entirely at fault to substantial sums. When sizeable amounts of money are awarded, courts are also acting as agents of redistribution, fashioning an ad hoc social safety net for victims and their families.

Recognizing Chinese courts’ tendency to spread losses through communities and to attach legal responsibility to relationships adds nuance to the conventional wisdom that when they ignore or stretch the law, it is due to concerns about maintaining social stability or to protect the interests of powerful parties. Most writing on Chinese law (including some of our own earlier work)Footnote 12 tells a story of courts that seek to apply the law except when obligations to maintain social stabilityFootnote 13 or to protect powerful economic interests push them to other outcomes. Looking at a large number of tort cases that involve largely accidental misfortune reveals other reasons courts stray from or stretch the law: to achieve outcomes that recognize the ethical as well as legal obligations that arise out of relationships. Courts also actively seek to ensure that losses are spread within communities, even when no one is at fault. In so doing, Chinese courts are active participants in the broader state project of creating a good society. To be sure, this is not a new view of Chinese courts. Nearly four decades ago, comparative law scholar Mirjan Damaska wrote about how activist states strive “toward a comprehensive theory of the good life,” such that law is “directive, even hectoring, … tell[ing] citizens what to do and how to behave.”Footnote 14 In the 1980s, when Damaska was writing, Maoist China would have been an archetypal example of an activist state. Today, our findings suggest that this activist orientation toward law persists, even if the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s theory of “the good life” has blurred to the point at which it is hard to discern much beyond the oft-repeated public commitments to socialist core values, Communist Party leadership, and continued economic growth.Footnote 15

If the role of Chinese courts is to help ensure a well-ordered society, is that stability maintenance work in another guise? On the one hand, resolving conflict and strengthening communities help bolster political stability in a broad sense. Judges, too, may well have stability on their minds, even when they talk about fairness or substantive justice in their written decisions. On the other hand, though, the cases discussed in this article have nothing to do with suppressing political opposition and there is rarely any indication that plaintiffs are inclined to gather even a few people to protest. For all that focusing on stability is a powerful stating point to understand Chinese courts, then, treating stability as the sole factor that explains when courts depart from the law obscures other values openly discussed in court decisions.Footnote 16 What becomes visible in cases dealing with misfortune is the caretaking role Chinese courts take on in managing relationships in society. In times of loss, Chinese courts actively intervene to ensure that those who have suffered are compensated, family and neighbourly ties are preserved, and emotional harm is acknowledged. To be sure, concerns about social stability may also be influencing courts’ approach to these cases. But the written opinions cite other values as well and the decisions lean heavily on relationships—even tenuous ones—to ameliorate the harm of accidental injury.

Worldwide, restoring equilibrium in a community has long been recognized as an important part of what courts do, particularly in small towns where disputants will remain neighbours long after the case concludes.Footnote 17 It is also a familiar theme in the literature on twentieth-century socialist legal systems, which tended to view trials as an educational opportunity to reinforce societal values by punishing outcasts.Footnote 18 Our point is that stretching the law to ensure communal sharing of losses has remained an important strand of Chinese legal culture even following decades of urbanization, a parade of legal reforms aimed at fostering stricter adherence to law, and a tightening of political control under General Secretary Xi Jinping. It routinely happens in big cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, as well as in rural areas. And when courts engage in loss-spreading, the economic and social implications take on a new dimension in the twenty-first century. On the economic side, court-ordered redistribution backstops state benefits and smoothes the pain of rising income inequality. On the social side, treating catastrophic loss as a community event marks a renewed attempt to create social solidarity though law.

2. Fairness in law and equitable liability

Chinese law includes numerous provisions that give courts discretion to consider fairness (公平) in their decisions, from contract law, to takings law, to intellectual property law.Footnote 19 Yet two of the most controversial legal provisions in Chinese-language scholarship do not actually use the term “fairness”—the equitable liability provisions of the 1986 General Principles of the Civil Law and the 2010 Tort Liability Law.Footnote 20 Most legal systems impose liability for personal injuries based on negligence, strict liability, or a combination of the two. Prior to 2021, Chinese tort law included a third category: liability based on the “actual circumstances.” Both Article 24 of the Tort Liability Law and Article 132 of the General Principles of the Civil Law state that if none of the parties is at fault for damages, they can nevertheless share liability “according to the actual circumstances.”Footnote 21 These “equitable liability provisions” authorized courts to allocate damages based on fairness in situations in which a defendant’s actions had contributed to harm but the defendant was not found to be negligent or strictly liable. Scholars report that the 1986 provision was inspired by a mixture of German, Yugoslav, and Soviet civil law,Footnote 22 and also that it reflected the relative lack of development of Chinese tort law in the mid-1980s.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, the equitable liability provisions were unusual when placed in comparative perspective. Although other legal systems permit the parties’ circumstances (including relative wealth) to be considered in determining damages in some circumstances, these factors come into play only after liability is established. In China, in contrast, courts were authorized to look to “actual circumstances” to impose liability, even absent negligence or strict liability.Footnote 24

The equitable liability provisions have been controversial in China. Much of the criticism centres on how equitable liability has been applied outside of its intended sphere of torts casesFootnote 25 or misapplied. For example, a study of 100 cases citing the provision found that nearly half involved a finding of fault, even though the provision is only supposed to apply when neither party is at fault.Footnote 26 Another criticism is that the language of “actual circumstances” in the law is stretched by courts to impose liability based on a wide range of factors, including the severity of damages, parties’ financial status, ethical concerns, and the goal of achieving social harmony.Footnote 27 Courts sometimes ignore causation to impose liability on defendants with only tenuous links to an accident because they have the ability to pay.Footnote 28 Indeed, widespread misapplication of the law was one factor that led legislative drafters to curtail the use of equitable liability provisions under China’s new Civil Code (which came into effect in 2021), limiting it to cases explicitly authorized by law.Footnote 29

In contrast to the robust debate over equitable liability in Chinese-language scholarship, however, the provisions have attracted scant attention in the English-language literature on Chinese law. One notable exception is a 2018 article by Chenglin Liu, who sees the “primary purpose” of equitable liability provisions as “maintaining social stability.”Footnote 30 Liu’s interpretation accords with a good deal of empirical work on Chinese tort law, which documents how courts sometimes stretch the law to ensure compensation. This is especially likely when cases are prone to giving rise to instabilityFootnote 31 and in cases involving insurance companies, hospitals, or other institutions seen as having deep enough pockets to help shoulder the cost of injuries.

Although prior work in both Chinese and in English offers important insight into the origin and use of the equitable liability provisions, this scholarship has also tended to focus on cases in which the equitable liability provisions are cited directly. In practice, however, courts often rely on equitable principles without citing the provisions, through reference to principles such as “taking the people as the basis,” “actual circumstances,” or simply basing an outcome on a court’s discretion.Footnote 32 Indeed, one of the insights gained from the methods we use in this article is that the use of equitable principles extends far beyond cases that cite the specific equitable liability provisions. Prior scholarship has generally also focused on the types of situations in which courts apply equitable liability and has not discussed the norms and relationships courts uphold in such cases.

3. Data and methods

Our primary source of data is 44.2 million Chinese court decisions, publicly released between 2013 and 2018 on a website run by the Supreme People’s Court called “China Judgements Online” (中国裁判文书网).Footnote 33 In order to navigate a data set this large, we combined computer-assisted content analysis with close reading. To start, we identified 9,485 court decisions citing either the equitable liability provisions of the Tort Liability Law or the General Principles of the Civil Law.Footnote 34 These were all cases we were confident would be concerned with substantive justice and equity-based adjudication. Then, we applied topic modelling, which is a text-mining tool that is frequently used to discover topics in large collections of documents, to the 9,485 decisions.Footnote 35 Topic modelling gave us a way to group this still-sizeable corpus into themes to select cases for close reading. Our topic model yielded 71 topics.Footnote 36 Since these topics are generated by a computer, a close read is needed to understand the context of each topic. Research assistants helped us assign each topic a label (e.g. worker injury cases, sports-related injury cases) by reviewing the high-frequency words associated with each topic and reading 20 cases associated with each topic.Footnote 37

In addition to topic modelling, we selected cases for close reading in two ways. First, we read decisions that included two specific phrases associated with fairness in the holding section of the opinion (“substantive justice” and “taking the people as the basis”). We read all 77 decisions that included the phrase “substantive justice” (实质正义) and a random sample of 200 of the 1,507 decisions that included “taking the people as the basis” (以人为本). Second, we read and coded a sample of 250 cases in three types of cases in which either our own background knowledge, conversations with legal professionals in China, or reading of the topic model suggested that courts were likely to give strong consideration to substantive justice: cases involving injuries to students at school,Footnote 38 child drownings,Footnote 39 and death due to excessive alcohol consumption.Footnote 40 We took this second step to try to uncover cases in which courts were strongly concerned with substantive justice but did not cite the equitable liability provisions directly. Indeed, our coding suggests that this happens fairly frequently. Although both child-drowning and death-by-drinking cases do appear in the topic model of equitable liability cases, the samples of cases that we read suggest that court decisions often reference the “actual circumstances” of the case or the court’s discretion to justify outcomes, without citing the equitable liability provisions. Altogether, our research team read 2,170 cases.Footnote 41 We are not aware of any prior scholarship that has attempted to look at these cases on this scale.

The advantage of this approach was it yielded a large and trans-substantive set of legal decisions, virtually all of which directly or indirectly considered fairness in resolving the case. The cases we read also came from across China, and included hundreds of cases from China’s rich provinces and big cities as well as from poorer, more rural areas, refuting the common argument that better-financed urban courts adhere closely to the law and would be more reluctant to consider amorphous, non-legal notions of fairness.Footnote 42 Although our primary focus is cases involving physical injuries in tort law, the topic model reveals how concerns about fairness have spread into other areas of the law as well, including employment law and sexual relations.Footnote 43 The disadvantage of our methodology is that written court decisions only tell us how cases turned out and the public justifications judges choose to offer for their decisions. They cannot tell us how judges thought about a case or what a judicial panel discussed in private. Further research interviewing judges or observing court proceedings is needed to better understand when and why judges frame their decisions in terms of fairness and whether that language cloaks other concerns.Footnote 44 But court decisions are not a bad place to start, as the primary place where judges offer public rationales for their decisions. In the cases we examine, courts often acknowledge fairness, equity, and justice as an explicit justification for their decisions, despite the risk that discussing values may open up the court to criticism for going beyond the law.

4. Substantive justice in and beyond the law: court practice

Reading thousands of cases through a topic model and guided reading suggests that what is fair depends at least in part on the underlying relationship between the parties. We divide the cases we read into two categories of relationship-based liability: participant liability and space-based liability (Table 1).Footnote 45 Neither type of liability is specifically recognized in Chinese law. Rather, they are what we call de facto doctrine, or common judicial solutions to a recurrent similar fact pattern. Below, each type of liability is illustrated with typical cases, followed by a discussion of the judicial rationale we see as implicit in the text of these decisions. Although it is difficult to know whether court-ordered compensation counts as a significant amount of money to the parties involved, we differentiate between two different logics of court-ordered compensation, depending on how much money changes hands. We see smaller awards where plaintiffs receive 20% or less of what they requested as a de minimis acknowledgement of trauma and understand larger awards to be a form of redistribution that shifts significant sums to victims and their families.

Table 1. Types of relationship-based liability

4.1 Participant liability

4.1.1 Social companions

In September 2016, a group of retirees went on a road trip together to Zhumadian, in Henan. At lunch, the owner of a restaurant warned the group about wasps in the area. While hiking later in the day, two of the retirees, a married couple surnamed Li and Cui, suffered bee stings and died. The trip had been organized informally through a “senior university” (老年大学), a social organization for retired cadres, but the court found no evidence that the senior university had done anything wrong. Instead, the court noted that all of the participants had shared the costs of the trip. Although there was no negligence and no way to anticipate the accident, the court reasoned that because the participants were members of a “temporary mutual self-assistance group,” they should share a portion of the loss and compensate the surviving family members. Citing the equitable liability provisions of the Tort Liability Law, the court ordered each defendant to pay 10,000 yuan in compensation.Footnote 46

The Zhumadian case is representative of a common theme that emerges from reading equitable liability cases: presence at the scene is often enough to give rise to a duty to compensate when a fellow participant is injured. We refer to this court-imposed obligation to share losses among a group of fellow participants as “participant liability.” In some cases, the defendant’s actions contributed to the plaintiff’s injury but courts find no negligence. In others, there is no causal link, only presence at the scene. Nevertheless, courts rely on arguments about fairness to ensure that plaintiffs receive some compensation. In a similar case to the bee-sting case, but this time involving surfing, the court ordered three defendants to pay compensation after their surfing companion drowned.Footnote 47 The court found no evidence that the defendants were negligent or had contributed to the accident, and stated that the death was the result of an accident. Nevertheless, the court ordered each defendant to pay 10,000 yuan in compensation in accordance with the equitable liability provisions of the Tort Liability Law, noting that they had shared the costs of the trip.Footnote 48

4.1.2 Drinking and illicit activities

Heavy social drinking is another shared social activity that likewise often gives rise to loss-sharing, even when the court finds the deceased to be wholly responsible for their own death. Thus, for example, in a case from Shenyang,Footnote 49 Mr Zhao died from a car accident after drinking with friends. The court found that Zhao’s friends, who had been eating and drinking with him to celebrate a birthday, were not responsible for the death and that Mr Zhao was “solely responsible” for the accident. Nevertheless, the court ordered the two defendants to pay Zhao’s surviving family members 40,000 yuan as “appropriate economic compensation” (应适当补偿经济损失为宜).Footnote 50 Similarly, in a case from Shandong,Footnote 51 Mr Xiao died of suffocation after drinking heavily with friends and riding his motorbike home. The court found that there was no evidence showing that defendants’ behaviour caused the death but nevertheless ordered each of the defendants to pay 33,900 yuan in compensation.

In other cases, courts appear to impose liability in part because defendants were engaged in a common illicit activity, such as gambling, despite there being no link between the injury and the activity. In a case from Inner Mongolia,Footnote 52 the victim was gambling with three other people, including one of the defendants, when a second defendant knocked on the door, pretending to be the police. The victim and one of the defendants then jumped out of the apartment window, apparently out of fear that they would be arrested for gambling. The victim died from a brain injury suffered during the fall. The court stated that there was no evidence that the defendants were at fault for the plaintiff’s death but nevertheless ordered the defendants each to pay 40,000 yuan in compensation, stating that it was doing so in consideration of the conduct of the two defendants and the “economic situation of the parties.”Footnote 53

4.1.3 Children

Courts’ emphasis on communal sharing of loss is even clearer when the victim is a child. In a series of cases, courts use equitable liability to order compensation to the parents of children who drowned while swimming, despite the lack of a causal link between the actions of the surviving children and the accident. Thus, for example, in a case from Sichuan,Footnote 54 a 15-year-old boy surnamed He drowned on a hot Friday afternoon in June while swimming in the river with four friends. Contrary to the claims of He’s parents, who brought the lawsuit, the court found that swimming had been He’s idea. None of his friends had goaded him into the water or to the dangerous middle of the river. Even so, the court ordered the families of the four other boys to pay compensation in order to “provide comfort” to He’s parents in light of their suffering and economic loss.Footnote 55 Even the family of the boy who spent the whole time playing games on his phone and never left the riverbank was asked to pay 1,000 yuan. In cases like He’s, it is not clear that significant sums are changing hands. Rather, courts seem to be focused less on meeting the economic needs of the victim’s family than on publicly acknowledging catastrophic emotional loss.Footnote 56

4.1.4 Sexual relationships

The idea that certain types of social interaction result in an obligation to compensate extends to sexual relationships. A good example comes from the city of Dalian in a 2015 case brought by the parents of a woman surnamed Zhang who died of a sudden cerebral haemorrhage while her boyfriend was at work.Footnote 57 Although the court found no connection between the boyfriend’s behaviour and the victim’s death, the “great suffering” (很大痛苦) caused by Zhang’s death was enough reason for the court to order Zhang’s boyfriend to pay the parents 40,000 yuan.Footnote 58 Even a one-night stand can be enough to trigger de facto legal liability for the death of a sexual partner. In a 2016 case from Hunan province, Ms Zhan was found dead in a hotel room after having sex with a former elementary-school classmate, Mr She. The two had gone to a Changsha hotel following a dinner the previous night and Mr She called for help when Ms Zhan did not wake in the morning. Should he have noticed that Ms Zhan was making unusual noises in her sleep and sought help earlier? Mr She argued that the two were not a couple and he had no way of knowing how she ordinarily slept. He also suggested that her death was the result of drug use. A police report found no evidence of foul play and the court ultimately decided that there was no evidence of negligence on She’s part. Regardless, the decision noted that Zhan was a widow and she left behind a son as well as an ageing parent. In light of the family’s financial situation, the court ordered She to pay 60,000 RMB in compensation.Footnote 59

Disputes over who should pay for an abortion are another context in which courts layer financial obligations on top of an extramarital sexual relationship. These cases also show how courts sometimes extend and blend tort law references to equitable liability with contract law claims based on fairness. Men are typically ordered to pay part of the cost of an abortion based on “the principle of fairness” (公平的原则), a phrase drawn from contract law, even when the court decides that neither party is legally at fault. These disputes are especially tricky because they often take place against the backdrop of a strained relationship. One such estranged couple came to a district court in Guangxi Province in 2012, having already lived through the death of a first premature child because they could not pay for an incubator, fighting over who should pay for a subsequent abortion. Relying on the equitable liability provisions from tort law, the court asked Mr Wu, the defendant in the case, to pay half the costs of terminating the pregnancy under the umbrella “principle[s] of fairness and upholding women’s rights.”Footnote 60 Notably, the court cited the equitable liability provision of tort law to justify its decision.Footnote 61

4.1.5 Rationales

What explains courts’ efforts to impose participant liability in such a wide range of social interactions, from social outings, to heavy drinking and illicit activities, to children playing together, to sexual relationships? Certainly it is not the law. Many of these cases do not fit the equitable liability provisions of the Tort Law, which require a causal link between defendants’ conduct and plaintiffs’ injuries. Stability also falls short as a full explanation, unless stability is defined to include every potentially unhappy litigant. It seems unlikely that the illicit gambler or the family of the deceased sexual partner was genuinely perceived as a likely petitioner or protester. What emerges in these cases is a particular view of relationship-based liability, which is that certain social interactions give rise to obligations beyond specific legal requirements. Rather than letting losses fall where they may absent a finding of negligence, Chinese courts send a strong message that participation in shared social activities requires a collective sharing of losses.

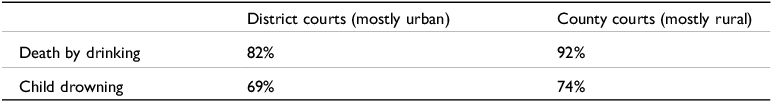

How predictable are the outcomes in these cases? To get traction on this question, we read and coded 250 cases of each of two types of cases that involve participant liability: child drowning and death by drinking. What we found is that courts overwhelmingly allocate at least some compensation to victims or the families of victims. Across a sample of 250 child-drowning cases, courts awarded damages 75% of the time.Footnote 62 In a sample of 250 death-by-drinking cases, plaintiff success was even more likely, with 85% of the cases resulting in damages paid to plaintiffs.Footnote 63 Victims also recover in both rural and urban courts.Footnote 64 Although victims are slightly more likely to be awarded compensation in rural courts, perhaps because a more communitarian logic holds sway in the tighter-knit communities of the countryside, plaintiffs are likely to receive compensation regardless of the location of the court (Table 2). The vast majority of lower court decisions across the country treat participant liability as a de facto doctrine and ensure that plaintiffs recover at least some money in recognition of their losses.

Table 2. Percentage of decisions that award compensation to plaintiffs

Typically, plaintiffs only receive a portion of what they requested. In our sample of child-drowning cases, plaintiffs received less than half of what they requested in 82% of cases and less than a quarter of what they requested in 55% of cases.Footnote 65 In the death-by-drinking cases, plaintiffs received less than half of their request in 85% of cases and less than a quarter in 57% of cases.Footnote 66 Clearly, courts are trying to split the difference between plaintiffs and defendants. Yet fairly substantial sums are also changing hands. The average award in a death-by-drinking case in our sample was 143,720 yuan and the average award in a child-drowning case was 118,274 yuan.Footnote 67 We also see little evidence that defendants are better placed than plaintiffs to shoulder losses, at least from what we can gather from the clues sprinkled throughout the text of decisions, particularly occasional references to defendants’ occupations. Rather, these cases generally appear to involve parties from the same economic background. Ordering damages in these cases, then, involves sharing the burden of loss within a community rather than channelling money from haves to have-nots. Do Chinese judges think about this kind of loss-spreading as part of their role in society, or do they take a harder-nosed view of it as a tactic to appease grief-stricken plaintiffs so that they neither appeal nor complain? It is impossible to say without interviewing judges and judicial attitudes are also likely to vary with the circumstances of the case. At least some cases are likely to be influenced by the moral judgment of judges and their views of activities such as drinking, gambling, and sex outside of marriage. But regardless of the view judges take of the parties involved in the case, or even how they view their role in society, the decisions in these cases are strikingly consistent: Chinese courts routinely impose an implied social compact that requires those present at the scene to share the burden of loss when things go awry.

4.2 Space-based liability: businesses and institutions as insurers

4.2.1 Businesses: bars, hotels, and bathhouses

Mr Song died following heavy drinking at the somewhat innocuously named Latte Bar, in Beijing.Footnote 68 Instead of suing his drinking companions, as in the participant liability cases above, Song’s parents sued the bar, arguing that its employees failed to meet their obligations to protect their customers.Footnote 69 But the bar’s employees had called an ambulance and had waited outside for it to arrive, leading the court to find no negligence or causal link between the conduct of bar employees and Song’s death. Nevertheless, the court noted that Song was a frequent customer at the bar, including the night of his death, and that the bar had profited from Song’s presence. The court thus ordered the Latte Bar to pay 120,000 yuan in compensation to Song’s survivors “according to equitable liability principles.”

Song’s case is emblematic of a second category of court-imposed obligation in tort cases: liability based on physical presence, most often from accidents that occur at a place of business or large institutions. Business owners, employers, schools, and hospitals are often ordered to share losses with their customers, employees, or students, even when there is no finding of negligence or even a causal link to the defendants’ actions. As in cases involving participant liability, courts use arguments about fairness to impose an implied social contract that businesses and institutions must share in the losses of those from whom they profit or those over whom they have control, even absent negligence.

Courts sometimes make the economic benefit rationale explicit. In a similar case to the Beijing case, from Henan Province,Footnote 70 the Yiyun Hotel was ordered to pay 20,000 yuan to the family of Mr Shang, who died in the hotel after checking in drunk. The hotel’s proprietor found Shang dead in his room the next morning. The cause of death was unknown and the family rejected an autopsy. The court stated that the hotel was not at fault but nevertheless cited the fact the hotel was financially benefiting from the victim’s presence and said the hotel had failed to meet its “ethical obligation to provide humanistic care” to its guests.Footnote 71

In the drinking cases, courts imply that businesses have some duty to care for their customers, or at least supervise them. In other cases, however, courts impose damages even when customers die of a heart attack on the premises. In a case from Liaoning Province, a court imposed liability on a public bathhouse, the Shenyang Tijia Women’s Club, after a 72-year-old customer, Ms Xu, died of cardiac arrest.Footnote 72 The family declined an autopsy and the court noted that the bathhouse had acted properly in calling an ambulance. Although the court said that the bathhouse had made “management errors” by failing to enforce the sign at the door refusing service to elderly customers in poor health bathing alone, it clearly stated that these errors did not cause Xu’s death. Nevertheless, the court stated that the bathhouse had an obligation to pay because it was financially benefiting from her presence. The court ordered 20,000 yuan in “appropriate compensation” to “balance the rights and obligations of the parties.” Similarly, a court in Guangdong Province ordered a health product shop to pay compensation to the family of a customer who died shortly after getting in a heated argument with the shopkeeper.Footnote 73 The shop had promised a free bag of eggs to anyone who attended a lecture about its products and an argument developed when the shop refused to give a bag of eggs to both the decedent and his spouse. Although the court found that the plaintiff failed to show that the shop caused the death, the decision used the Tort Liability Law’s fairness principle to order the shop to bear 20% of the plaintiffs’ loss “according to the actual situation” of the case. The court appeared to be signalling that it disapproved of the shop’s marketing tactics, even if there was no direct link to the victim’s death.

4.2.2 Employers

Courts also routinely rely on arguments about fairness based on the equitable liability provisions of the Tort Liability Law to impose liability on employers for injuries or deaths to employees, even when the harm is unrelated to employment. The implied argument is that the employer benefited from the victim’s labour and also that whoever has physical control over a workplace is responsible for anything that happens there, regardless of cause. Thus, for example, after a bus driver became sick and died on the job, the court asked both the company and the company owner to pay damages, even though there was no link between the death and the employee’s job.Footnote 74 The decision noted that the plaintiff was working for the bus company at the time of his death and that he acted to the benefit of the company when he managed to stop the bus without harming passengers when he became ill.Footnote 75 Similarly, a court in Jiangxi relied on arguments about fairness when a worker died of a bee sting while working on a construction site.Footnote 76 The court ordered the employer to pay 110,000 yuan in compensation.Footnote 77 In similar cases involving sudden deaths at work, courts likewise found no negligence or causation on the part of the employer but awarded damages “according to the actual circumstances”Footnote 78 or based on “fairness.”Footnote 79 These cases place employers in a custodial or quasi-parental role vis-à-vis their employees and hold them responsible for anything that happens to workers on the job.Footnote 80 In so doing, they extend far beyond employment law and regulations on work-related injuries.Footnote 81

Other cases extend employers’ obligations to compensate even beyond the workplace. In one such case, the victim was murdered on her way to work at a Henan Internet cafe. The court found no connection between the murder and the employer, but relied on equitable liability principles to award 20,000 yuan in damages.Footnote 82 The court justified compensation “according to the actual circumstances” of the case and included a note that the murderer had been executed without paying any compensation to the victim’s family.Footnote 83

4.2.3 Large institutions

A third example of a space-based relationship giving rise to an obligation to compensate is between large public institutions, such as schools and hospitals, and the people who use them.Footnote 84 The principle is that injuries that occur on the premises of public institutions or that befall those under their supervision deserve compensation, even when there is no link to defendants’ conduct. Litigation resulting from injuries suffered by children at school is a central and commonFootnote 85 example of how courts have extended tort law to force certain public institutions to serve as virtual insurers of harm suffered on their watch.

Chinese law has clear provisions regarding injuries to children at school. For injuries to children who are 8 years old or younger (10 years old or younger prior to 2017), schools have the burden of proof to show that they were not negligent.Footnote 86 For older children, the burden of proof is on plaintiffs.Footnote 87 In practice, however, courts considering claims made on behalf of children injured during the school day virtually always order the school to pay compensation, even in cases involving older children in which plaintiffs fail to introduce evidence that schools were at fault.

In numerous cases, courts find that schools were not responsible for harm suffered by students but nevertheless order compensation according to principles of equity. Thus, for example, in a case from Xixiang County in Shanxi,Footnote 88 a fifth-grade student surnamed Xu injured his arm when he fell while running in an 800-metre race. He was hospitalized for 10 days. Upon returning to school, Xu re-injured his arm when another student collided with him while exiting the classroom, leading to a second hospitalization and surgery. The court found that the school had taken all necessary steps to ensure the safety of its students and was not negligent. Nevertheless, the court ordered the school to assume 30% of the cost of the first injury, roughly 11,000 yuan, “in accordance with the actual situation.”Footnote 89 Similarly, in a case from Nanjing,Footnote 90 a first-grader surnamed Chen was injured on the playground. He was running away from a child who was chasing him and collided with another classmate, suffering an injury to the nose that led to a 5-day hospitalization. The court found that the school had not acted negligently, noting also that the children “were playing a game and their play should not be restricted,” but nevertheless ordered the school and the guardians of each of the two children involved in the accident to each pay 2,000 yuan in compensation.

In some cases, courts explicitly acknowledge that they are guided by the view that those who suffer an injury should receive compensation, regardless of whether anyone acted negligently. In a case from Chongqing,Footnote 91 plaintiff Fan injured his arm while training for a high-jump competition and spent 48 days in the hospital. The court found that Fan himself was primarily responsible for the accident due to his own lack of ability rather than anything related to the quality of school facilities or oversight. Nevertheless, the court relied on “substantive justice” to assign secondary responsibility to the school and order them to pay 40% of the harm suffered. A situation in which there is no one to “settle the bill” for Fan’s injury (无人买单的情形), the decision explicitly states, would violate the principle that “where there are damages, there should be remedies” (有损害则应有救济).Footnote 92

Schools are at times held liable even for injuries that occur outside of school, reinforcing the idea that they bear broad responsibility for their students’ wellbeing. In September 2014, a 9-year-old child surnamed Wang drowned in a river flooded by heavy rain while walking home from school at lunchtime. Although a Henan court found that the death was not connected to the school, it nevertheless ordered the school to pay 50,000 yuan in compensation to Wang’s family, noting that the death had caused “very large emotional harm” to his parents.Footnote 93 Likewise, in a case from Beijing,Footnote 94 the plaintiffs’ son was a student at a boarding school on the outskirts of the city. After returning home for the weekend, he failed to return to school on Sunday. He was found drowned 6 days later and the police concluded that there was no evidence of a crime. The court noted that the victim’s death had not occurred at school but that, in accordance with the “case situation,” it was using its discretion to order the school to pay 20,000 yuan in compensation.

To check the representativeness of these cases, we read and coded 250 cases that discussed injuries that occurred at school. Courts awarded damages in 95% of cases (207 of 217 cases with data on outcomes),Footnote 95 confirming that schools are virtually always asked to pay for injuries that occur to children at school. Students, and the families of students, also recover fairly significant sums. In the school injury cases, plaintiffs received 50% or more of their demands in 60% of cases,Footnote 96 with an average award of 81,800 yuan.Footnote 97 The takeaway of this coding exercise is clear: schools assume responsibility for most of the damages suffered by children at school, at least during the time period covered by our data set. Legal provisions that state that schools are not responsible if they can disprove negligence (for injuries to younger children) or if the plaintiff fails to show that schools were negligent (in cases involving older children) appear largely irrelevant. Typically, courts stretch to find some negligence, often relying on a general statement that schools failed to fulfil their duty to adequately supervise.Footnote 98

Following the same logic as for schools, courts also often push hospitals into the role of social insurer. Two topics in the topic model concerned medical disputes,Footnote 99 with courts generally imposing compensation on hospitals for catastrophic harm to patients, even absent evidence demonstrating negligence or medical malpractice. In a case from Jilin,Footnote 100 for example, the court imposed liability on a hospital that had initially treated a patient who had been hit by a car while walking home after drinking. The court found that the hospital had “made some mistakes,” though the mistakes did not contribute to the patient’s death. However, the court also noted the importance of balancing the interests of hospitals with “the weak position of patients” and the importance of preventing patient-hospital conflict.Footnote 101 Likewise, in a case from Inner Mongolia, plaintiffs sued after a man died while waiting for an ambulance. The court found no evidence that the delay contributed to the victim’s death. Nevertheless, the court ordered the hospital to pay compensation because the ambulance “should have been more prompt” and the plaintiff’s family was in a “difficult financial condition.”Footnote 102

4.2.4 Rationales

In these cases, courts treat liability as a spatial concept. Sharing physical space triggers financial obligations. Businesses are asked to pay for accidents to customers on their premises, just as ordinary people are asked to pay when they are present at the scene of an accident. Courts are particularly likely to invoke space-based liability when the space is being used for profit or when the space-owner is a public-facing institution such as a school or a hospital.Footnote 103 In both situations, courts ask defendants to assume custodial responsibility for those who enter their space, including sometimes injuries that happen off-site. In the case of businesses, part of the logic appears to be that profiting off customers and employees triggers an obligation to care for them. In cases involving state-run institutions, the assumption that the state will pay is anchored in a long history of state paternalism that pre-dates the CCP, and is also a recurrent theme of CCP governance and contemporary civil litigation.

Reading a range of space-based liability cases highlights variation in the amount of money that changes hands. Sometimes, especially when defendants are closer to struggling mom-and-pop shops than deep-pocketed corporations, courts award fairly minimal sums. In these cases, courts’ logic appears similar to the vision of collective loss-sharing that animated the participant liability cases. But more substantial awards are possible. Especially in cases involving (relatively) rich business owners or state-run institutions, courts shift a fair amount of money from society’s haves to its have-nots. Court-ordered redistribution effectively creates a social safety net for families experiencing emotional trauma and economic loss and, as legal scholars writing in Chinese have noted, helps plaintiffs recover in situations in which neither party has insurance.Footnote 104

Another way of thinking about participant liability and space-based liability is as two implicit rationales that Chinese courts use to adjudicate cases involving bad luck and catastrophic loss. To determine who should pay—and how much—Chinese courts look to the law, but also to unwritten expectations about the responsibilities triggered by certain types of relationships. Some types of cases can also be decided according to either logic. Although the vast majority of decisions in child-drowning cases, for example, impose participant liability on the families of other swimmers, we also encountered a few space-based liability cases in which courts asked adjacent property owners with no link to the accident to pay compensation. In one such case, which involved a local boy who drowned in a river, a Hunan court ordered a nearby business that had profited from selling stones taken from the river to pay 50,000 yuan in compensation to the victim’s family. The court acknowledged that there was no link between the stones and the death, but noted the massive loss suffered by the parents, whose 14-year-old child “had left the world without first repaying his parent’s kindness and upbringing.”Footnote 105

To be sure, neither participant liability nor space-based liability are entirely new ideas. Legal culture is hardy and, at a minimum, Chinese courts are drawing on a centuries-old practice of attaching legal obligations to dyadic relationships as well as a twentieth-century socialist tradition of using law to strengthen social solidarity. The Qing Dynasty Code, to take one well-known historical antecedent, adjusted criminal penalties depending on the relationship between the parties. A son who struck a parent, for example, was punished far more harshly than an assault on a non-parent.Footnote 106 In the more recent past, twentieth-century socialist states leaned heavily on law to strengthen social solidarityFootnote 107 —a legacy that resurfaces in Chinese courts’ impulse to ask the community collectively to share in catastrophic loss. Legal historians, of course, would expect to see these continuities and could doubtless identify many more connections between past and present. For observers who are less attuned to history, however, these historical continuities serve as an important corrective to the idea that China is forging an entirely new model of justice under Xi Jinping. At the same time, too, the cases we read also show Chinese courts innovating as society changes, particularly by starting to assign legal responsibility in a wider range of relationships, such as sexual relationships outside marriage. Another emergent dyad is the relationship between schools and businesses, and the people who either use them or are employed by them. Chinese courts routinely ask schools and businesses to take financial responsibility for accidents that involve their employees, customers, or students beyond what is legally required or take place on their premises (or even just nearby). The Chinese courts reflect—and also re-enforce—a worldview that social order is sustained by family, community, commercial, and institutional relationships, and that part of their role is to make sure these relationships are maintained.

5. Implications

In any legal system, cases involving misfortune are both rare and also routine. When they arise in the Chinese legal system, courts often turn to two de facto doctrines—participant liability and space-based liability—to craft solutions that appeal both to notions of fairness and to the practical need to ensure victims receive some compensation. The range of cases this article examines reveals that courts stretch the law to ensure that compensation is paid and loss is acknowledged. Close reading also permits insight into how courts think about the idea of fairness and the types of relationships courts view as carrying obligations.

Spreading losses through a community also helps smooth the rough edges of one of China’s most pressing policy problems: rising economic inequality. Wealth concentration has sharply increased in twenty-first-century China, as it has around the world, with the wealthiest 10% controlling 67% of China’s wealth.Footnote 108 Against this backdrop, courts that invoke substantive justice, fairness, or “actual circumstances” to determine who needs assistance and who is best able to bear the burden of compensation are backstopping a weak social welfare system. Particularly when significant sums change hands, the courts are blunting the sharp edges of inequality by redistributing wealth. Some instances of redistribution highlight the diverse interests of different parts of the party-state, as the courts impose liability on institutions with relatively deep pockets, such as schools, hospitals, and insurance companies. And some instances of redistribution involve courts asking ordinary people to chip in for compensation in cases involving injuries or death. It is hard to tell from the text of these decisions whether defendants are easily able to spare the money. It seems likely, though, that court-ordered compensation would sometimes be a stretch and that the point of loss-sharing is as much social and emotional as economic. Chinese courts treat catastrophic loss as a community event and, in so doing, use damage awards to signal recognition of traumatic loss and of the social obligation to support others.

Future research exploring whether relationships also surface as the guiding principle outside of tort law would also be welcome. One area of law with clear parallels is family law—another place in which Chinese courts plainly take a relationship-centred view of the world and ask themselves what is fair within the context of that relationship.Footnote 109 After all, the parent-child relationship is a dyad so central to China’s social structure that children’s financial obligation to care for their ageing parents is written into law.Footnote 110 Although the number of parent-versus-child lawsuits is dwarfed by the number of ageing parents in China, they regularly arise and courts virtually always find in favour of elderly plaintiffs seeking support from their children. In the Supreme People’s Court’s own analysis of over 52,000 lawsuits filed in 2016 and 2017, the courts either supported or partially supported parents’ claims 98.5% of the time.Footnote 111 In elder-care cases, Chinese courts also sometimes not only shift money between the parties, but also take it upon themselves to order children to visit or care for their parents. Inheritance law, too, also is centred on relationships. Rather than dividing inheritance equally between the closest living relatives, as would be the default rule in many jurisdictions, Chinese law empowers courts to reward potential heirs who supported the deceased, both financially and emotionally, especially by shouldering the burden of end-of-life caregiving.Footnote 112 In family law too, then, we would expect to see Chinese courts routinely working within the law, and sometimes pushing beyond it, to manage relationships.

What about the future? Will Chinese courts continue to use their discretion to compel loss-spreading through a community? Certainly, China’s new Civil Code tries to limit judicial discretion in this realm. The Civil Code restricts the use of equitable liability to a narrow set of cases involving those with diminished capacity.Footnote 113 In addition, Article 1176 states that voluntary participation in a risky recreational sport releases other participants from liability for accidental injury.Footnote 114 The new provision is in direct contrast with a number of cases in our data set in which such injuries led to a sharing of costs among participants and makes clear that future cases should not be decided based on participant liability. Recent media articles, too, have celebrated courts that adhere strictly to the law rather than bowing to the popular logic of “whoever dies is in the right.”Footnote 115

Yet ambivalence remains inside the party-state about whether Chinese judges should strictly follow the law or allow other principles to influence their decisions. As a result, participant liability and space-based liability are likely to be challenging to stamp out.Footnote 116 Just a month after the encyclopaedic Civil Code trimmed back judicial discretion in the use of equitable liability principles, the Supreme People’s Court issued a Guiding Opinion directing judges to draw on socialist core values in deciding cases, especially cases of public concern.Footnote 117 The Guiding Opinion, the latest in a series of party and Supreme People’s Court documents stressing socialist values, asks judges to integrate non-legal ideas into legal decisions. Early research looking at judicial decisions shows that judges use socialist values to allocate liability,Footnote 118 which suggests that social and space-based liability considerations may resurface, reframed in socialist language. Chinese judges continue to be asked to bend the law toward fairness and morality—even though parts of the legal profession and the party-state would prefer to anchor judicial legitimacy in strict fidelity to law.Footnote 119 Nor is the party-state necessarily interested in letting popular ideas about fairness seep into judicial decision-making. Rather, the party-state is taking a leadership role in defining moral norms itself, sometimes building on already-existing cultural scripts and sometimes modifying familiar ideas to better serve the party’s own political priorities. The CCP is meant to be the ultimate moral authority, with courts assigned a key role in moulding social solidarity.Footnote 120

Ultimately, is this brand of court-imposed social solidarity successful in increasing the popular legitimacy of the courts or of the Chinese Communist Party? Future research will want to explore how defendants react to decisions that impose participant liability or space-based liability absent negligence and investigate whether court-ordered compensation is actually paid. It is also important to understand how these decisions are received in the broader community. Is there a popular sense that “someone ought to pay” when misfortune strikes? If that sentiment is widespread, then decisions based on participant and space-based liability will be received as righteous, both as a form of redistributive justice that channels money to the needy and as an official emotional acknowledgement of tragedy. And if that sentiment is widespread, strictly following the new and voluminous Civil Code may carry its own risks, at least when the code diverges from popular understandings of who should pay when misfortune strikes.

Acknowledgements

We thank audiences at the University of British Columbia, the 2021 West Coast China Law Workshop, and the University of Hong Kong for their feedback. Thanks are also due to William Alford, Madlav Khosla, John Zhuang Liu, Eva Pils, and the two anonymous reviewers from AJLS for comments that helped improve the piece. We are grateful to the team of research assistants at Berkeley and Columbia who assisted with this project. Research for this paper was supported in part by the Stanley and Judith Lubman Fund and the Stephen H. Case Faculty Research Fund at Columbia Law School.