Chylothorax is defined as the accumulation of chyle in the pleural space. Chyle, derived from the word ‘Chylos’ in Greek which translates to juice, is a milky opaque fluid that is rich in triglycerides and chylomicrons. Reference Rudrappa and Paul1 Chylothorax is formed after a damage to the thoracic duct where chyle leaks from the lymphatic drainage system into the pleural cavity. It is a rare but serious condition that mostly manifests after thystemicoracic and cardiac surgeries. Reference Reisenauer, Puig and Reisenauer2 In children, the incidence of post-operative chylothorax has ranged from 1 to 6.6% in some studies. Reference Panthongviriyakul and Bines3 It is considered a serious post-operative complication because it has the potential to cause significant morbidity and mortality. This can range from malnutrition, increased length of stay and prolonged ventilator dependence to nosocomial infections and death. Reference Akbari Asbagh, Navabi Shirazi and Soleimani4–Reference Wolff, Silen and Kokoska6 Chylothorax is more common after complex cardiac surgery with a particularly high incidence after Fontan operation. Reference Kahraman, Keskin and Khalil7

It is crucial to have a timely diagnosis of chylothorax as well as adequate management. There are several treatment modalities described to approach chylothorax post-congenital cardiac surgeries. They are classified into conservative, medical, and surgical treatment options. Reference Mitchell, Korones and Berendes8 In this paper, we describe a child whose chylothorax occurred during the recovery time from the Fontan operation which has only resolved after the use of corticosteroids. We will also present comprehensive review of the literature regarding chylothorax and its management.

Methodology

This review was conducted in September, 2021. The literature review is up to date, and all selected articles were critically appraised for relevance and validity. A comprehensive search was done using Ovid Medline (19462021), PubMed, and google scholar. The references of the retrieved articles were checked for validity and relevance. We used the following MeSH Terms and keywords: chylothorax – chylothoraces – chylous – chyle leak – lymph fluid – thoracic duct injury – chyle effusion and were combined with adrenal cortex hormones – corticosteroids – steroids. The search was limited to the pediatric population. No limitations were made on the type of studies, year of publications, or country of origin. Articles were included if they are published in the English language and if they reported on cases of chylothorax in children or on prevalence and incidence. Additional papers were considered from the references of selected articles.

Case presentation

This is a 4-year-old girl, diagnosed with unbalanced atrioventricular canal and dominant right ventricle at birth. At 18 months, she had undergone a bidirectional Glenn procedure. At a later stage was admitted to our hospital for Fontan surgery. On physical exam, she had regular S1 and S2 heart sounds with grade II systolic ejection murmur heard best at the left lower sternal border. A fenestrated Fontan operation was done through a cardiopulmonary bypass. Post-operatively, trans-esophageal echocardiography showed good function with no aortic valve regurgitation. Three chest tubes were inserted intra-operatively, one in each pleural space, and one in the mediastinum. The chest tubes were removed on day 10 after minimal drainage. She was discharged home on Furosemide and Aspirin.

Ten days after discharge, she presented with desaturation down to 70% as well as cough and tachypnea, and she was admitted to the pediatric ward. A chest X-ray revealed significant bilateral pleural effusion. She was treated with diuretics with clinical improvement and discharged home on furosemide, Aspirin and spironolactone.

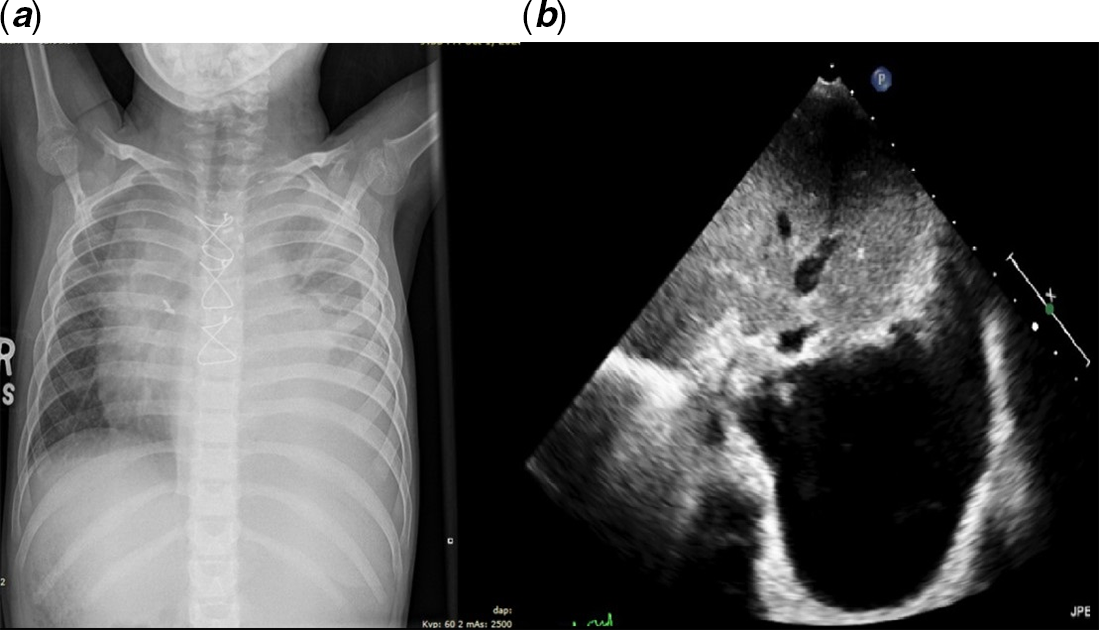

Symptoms recurred 14 days later, and she was complaining of dyspnea and tachypnea. She was re-admitted to the pediatric ward. A chest X-ray was done revealing a large left side pleural effusion (Fig 1a). Echocardiography revealed moderate to large pleural effusion on the left side (Fig 1b). She underwent ultrasound-guided drainage with left sided pleural pigtail catheter insertion by the interventional radiologist that drained milky fluid. Studies on the fluid revealed: white blood cell count of 9700/cu.mm, and triglycerides level of 400 mg/dL which was consistent with chylothorax. Gram stain and culture were negative. The chest tube drained around 1000 ml of milky fluid in the first 24 hours following insertion. The patient improved markedly. The catheter was left in place for around 10 days and was removed following minimal drainage. She received zero-fat diet, given middle-chain-fatty acid oil supplements, encouraged to ambulate, and monitored on the floor on a telemetry. A follow up chest X-ray on showed minimal left pleural effusion. Therefore, she was discharged home on Aspirin, Furosemide, and a zero-fat diet.

Figure 1. ( a ) and ( b ) represent the chest X-ray and the echocardiography images of the patient before drainage.

The patient was followed regularly in the pediatric cardiology clinic. She was having persistent small to moderate left pleural effusion on the echocardiogram howver she was clinically doing fine. 4 months following her discharge from the hospital, the patient presented with dyspnea. Echocardiography revealed an increase in the size of the left-sided pleural effusion, good cardiac function, and patent Glenn and Fontan connections. Therefore, she was started on Prednisone 6 mg twice daily after meals with a zero-fat diet. Ten days later she had significant improvement with good bilateral air entry on auscultation and only a small left pleural effusion on echocardiography. Prednisone was weaned over 4 weeks gradually until it was stopped. Follow up after 2 weeks showed complete resolution of the left pleural effusion, and the patient was allowed to start a low-fat diet, which persisted for 2 months, while still maintained on Aspirin and Furosemide once daily. No issues were encountered when the patient was restarted on a regular diet during the last follow up.

Discussion

Epidemiology

Chylothorax can arise due to congenital malformations, genetic syndromes, trauma, and conditions of high central venous pressure (thrombosis of the superior vena cava or subclavian vein Post-Fontan surgery, right-sided heart failure), among others. Reference Soto-Martinez and Massie9 While the most common cause remains cardiac surgery, the prevalence of chylothorax arising from right heart failure is not low. High venous pressure can increase abdominal lymph production, but the stiffness of the veno-lymphatic junction limits lymphatic flow. The other mechanism is having high pressures in the left subclavian vein that slows down lymphatic drainage. Reference Villena, de Pablo and Martin-Escribano10 In a national study by Haines C et al, 172 children with post-operative chylothorax in the United Kingdom, the most reported cases manifested after the Fontan procedure and the repair of Tetralogy of Fallot. Reference Haines, Walsh and Fletcher11 In another study by Chan EH et al, the incidence of chylothorax post-cardiac surgery was the highest in Fontan procedure and heart transplantation. Reference Chan, Russell and Williams5 The risk factors for chylothorax post-cardiac surgery in children include younger age, lower body weight, presence of genetic syndromes, the complexity of the operation, secondary chest tube closure, vein thrombosis, extended cardiopulmonary bypass time, longer cross-clamp time, and a higher annual hospital volume.

Endogenous glucocorticoids are known to reduce the amount of protein in most tissues by increasing the rate of extrahepatic protein degradation. This helps the liver to manufacture more plasma proteins from free amino acids. More fluid moves directly from the interstitial area into the bloodstream as plasma oncotic pressure rises, leaving less fluid for the lymphatics to empty. This action may be beneficial in reducing lymph flow long enough to restore normal lymph outflow. Reference Mery, Moffett and Khan12,Reference Biewer, Zurn and Arnold13

Anatomy and pathophysiology

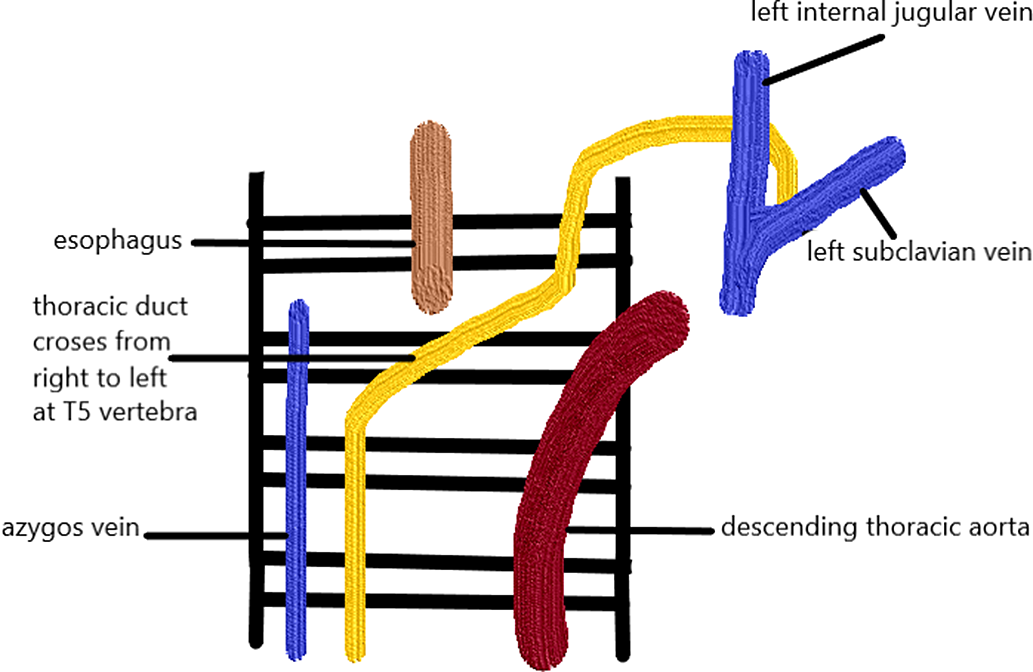

The thoracic duct starts from the abdomen at the cisterna chyli at the second or third lumbar vertebra level. Reference Phang, Bowman and Phillips14 It then ascends on the right side of the vertebral column and ventral to the aorta and azygos vein to reach the posterior mediastinum. Reference Kiyonaga, Mori and Matsumoto15 However, the course may have several anatomical variations. In 40% of the individuals, variations in the upper and lower thoracic duct segments exist in addition to differences in termination points Reference Phang, Bowman and Phillips14 (Fig 2). An injury to the thoracic duct below the fifth-sixth thoracic vertebrae leads to right chylothorax, whereas injury above that level leads to left chylothorax. Reference Valentine and Raffin16 Chylothorax may be caused by thoracic duct injury in which the risk is increased in, increased superior vena cava pressure leading to lymphatic congestion as in patients who undergo the Fontan operation.

Figure 2. Anatomy of the lymphatic duct.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

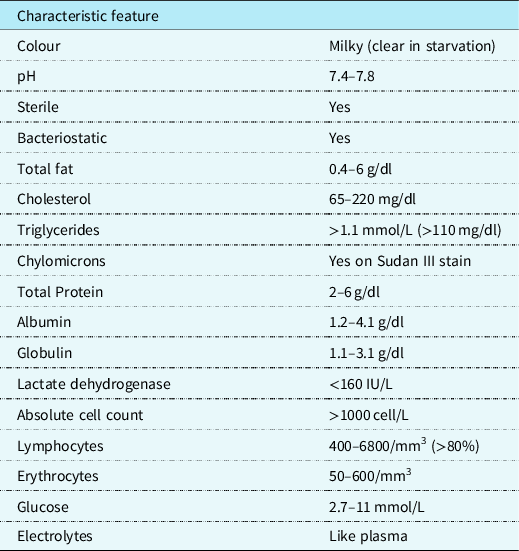

Clinically, the milky appearance of the fluid takes time to accumulate. Thus, early in the post-operative phase, the fluid may range between bloody and serous. Initially, the quantity of long-chain triglycerides in the diet is small. This is responsible for the lymphocytic predominance of the fluid. As the diet regimen advances, the fluid may become milky. Similar to pleural effusion, this manifests on a chest X-ray. Computed tomography scans, lymphangiography, and lymphoscintigraphy are some imaging studies that may be used to identify the site of the chyle leak. Reference Sharma, Wendt and Rasmussen17 Patients who are not intubated may be asymptomatic or express respiratory distress symptoms. The severity of the manifestations depends on the amount of fluid present and the rate of accumulation. In rapid conditions, hemodynamic instability may be present. Reference Soto-Martinez and Massie9 Patients with chronic chylothorax may present with signs of immunosuppression and malnutrition such as weight loss and muscle wasting. Reference Faul, Berry and Colby18 To confirm chylothorax, a sample taken by thoracocentesis must be tested by biochemical analysis (Table 1). Reference Buttiker, Fanconi and Burger19–Reference Ahmed23 In post-operative patients with decreased dietary fat content, the fluid may not be milky at the beginning. Reference Mery, Moffett and Khan12 The mainstay of diagnosis is the presence on chylomicrons on Sudan III stain with a higher triglyceride amount than found in the plasma. Reference Ahmed23 This is in addition to a lymphocytic predominance and presence of other products of digestion such as electrolytes and vitamins. Reference Buttiker, Fanconi and Burger19

Table 1. .Characteristics and biochemistry analysis of chyle.

Management

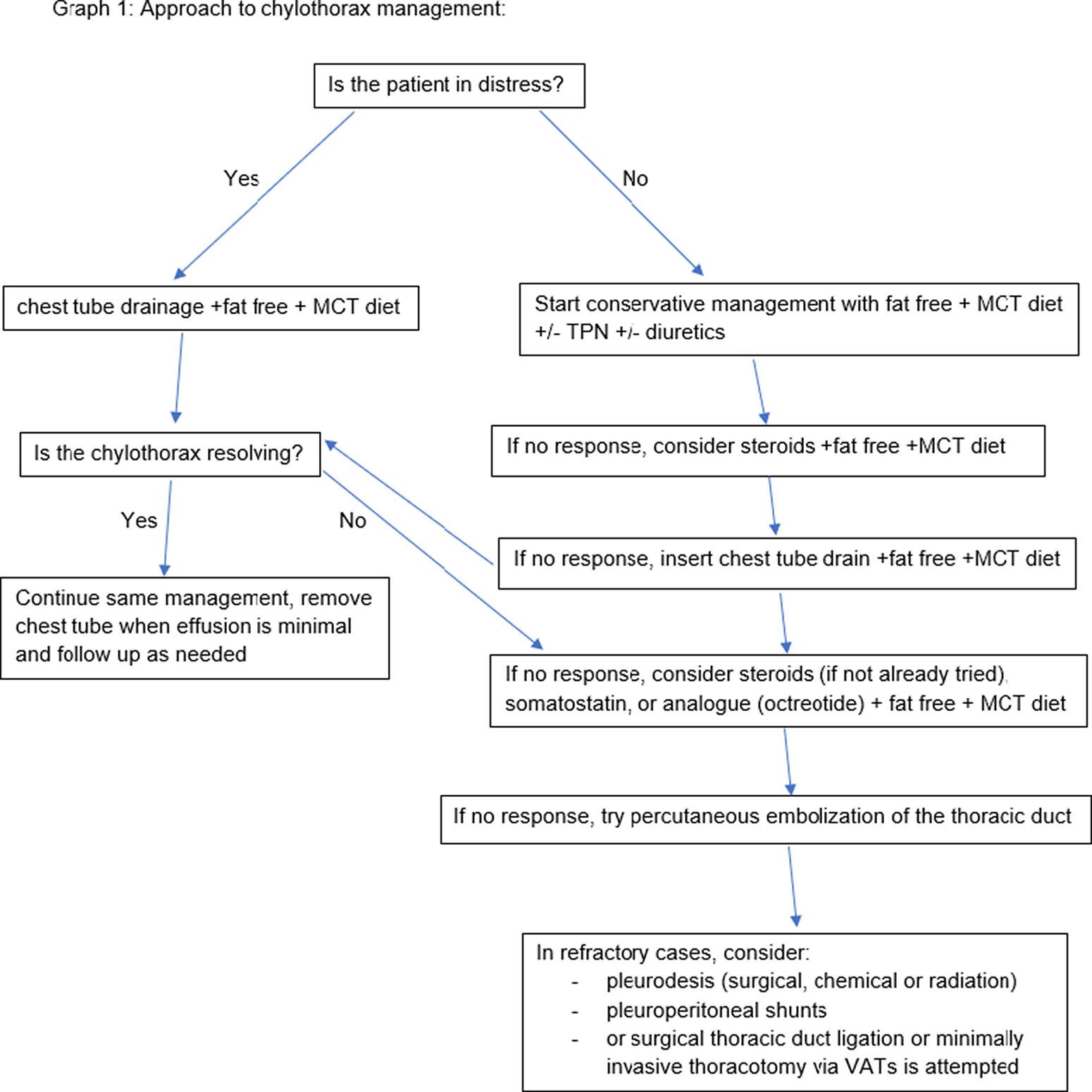

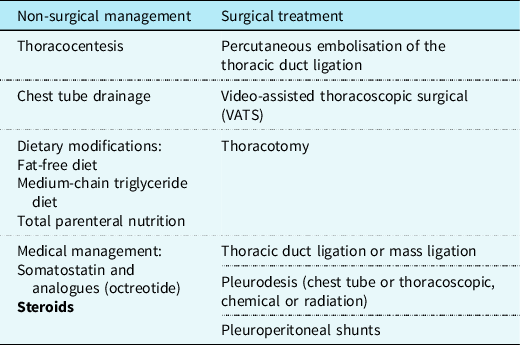

Management of chylothorax can be divided into two components: non-surgical and surgical. Our institutional strategy is presented in Table 2. Reference Rudrappa and Paul1 The aim is to provide symptomatic relief from the chyle effusion and to decrease or stop chyle accumulation. Reference Sharma, Wendt and Rasmussen17 If the patient is in acute distress, then the initial step is drainage through thoracentesis for confirmation of diagnosis and symptom relief otherwise conservative management can be started immediately if highly suspected (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Institutional approach to chylothorax.

Table 2. .Management of Chylothorax showing the available treatment modalities and steroids added as a new effective treatment option.

Medical

Initially, in the first days after the operation, the patient feeding will be started gradually when the patients conditions allow this. Patients diagnosed with chylothorax are started on zero-fat diet with the exception of medium-chain-triglycerides. Reference Biewer, Zurn and Arnold13 The benefit of using medium-chain-triglycerides in chylothorax is that it is absorbed directly into the portal system bypassing the intestinal lymphatics and thus the thoracic duct. If the patient cannot tolerate oral intake, the chyle output is high or the central venous pressure was >15 mmHg; then a more aggressive approach might be needed. Some patients may be placed on total parenteral nutrition. Reference Biewer, Zurn and Arnold13 Drugs to decrease the central venous pressure such as diuretics, sildenafil, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors can be used. Additionally, heparin for management of thrombosis or a cardiac catheterisation to treat and relieve the obstruction may be attempted. Endogenous hormones such as somatostatin or octreotide (a long-acting somatostatin analogue) can be used. Reference Roehr, Jung and Proquitte24

Corticosteroids

Steroids were used as a treatment of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, and hence would also be used to treat secondary chylothorax resulting from autoimmune diseases. The concept of using steroids to treat post-operative chylothorax originated from its success in treating autoimmune diseases. Reference Fakhri, Abutaqa and Abdulhalim25,Reference Manzella, Dettori and Hertimian26 Once steroids were administered, our patient’s chylothorax resolved. The success of steroids in treating autoimmune diseases supports the hypothesis post-operative chylothorax could in fact be due to an inflammatory component. This led to the belief that chylothorax canrespond to steroids. Steroids have been reported to effectively treat congenital and spontaneous chylothorax in patients with congenital anomalies. Reference Goens, Campbell and Wiggins27 Steroids have anti-inflammatory properties that may help lower the tone and thus prevent volume congestion in the thoracic duct. We reviewed the literature and found very scarce evidence on the use of steroids to treat chylothorax following cardiac surgery in the pediatric population. Dogan et al published a 10-year experience on pediatric chylothorax. They reported eight patients, six of which had chylothorax refractory to somatostatin or octreotide. Dexamethasone was added and lead to the complete cure in three patients. Reference Kahraman, Keskin and Khalil7 In another inspiring attempt by Rothman et al, a patient developed chronic chylothorax lasting 1 year after the Fontan operation which was refractory to pleurodesis and pleuroperitoneal shunting. Prednisone twice daily with aspirin was started leading to the resolution of the effusions. After resolution, steroids were discontinued which led to the recurrence of the pleural effusion. Finally, the last steroid trial with a 6-month tapering period was effective. This reiterates the importance of the steroid dose and duration in the resolution of the effusion. Reference Rothman, Mayer and Freed28 In a large national database study, more than 3500 children with chylothorax were identified. The use of corticosteroids was assessed in these children after undergoing cardiac surgery. While the authors did not delineate the timing of steroids, they have described the results of giving different classes of corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone was significantly associated with a reduced length of stay without affecting mortality or need for surgical intervention. Dexamethasone was associated with a significant decrease in mortality, length of stay and the need for surgical intervention. On the other hand, prednisone had no effect on any of the outcomes. Reference Loomba, Wong and Davis29 This is a similar experience with what our patient went through, she had unsuccessful treatment trials such as dietary modifications and diuretics, but treatment was finally successful after using steroids with proper tapering.

Protein-losing enteropathy

Moreover, another important sequel of the Fontan procedure is the presence of protein-losing enteropathy. This phenomenon is characterised by protein loss in the enteric system along with low protein and albumin levels in the blood. Reference Johnson, Driscoll and OʼLeary30 It can arise spontaneously due to dilated lymphatic vessels, but it is more common secondary to cardiac operations such as Fontan. Fontan operation provides a unique environment consisting of elevated central venous pressure. In fact, Fontan has become the most common cause of protein-losing enteropathy. Reference Crupi, Locatelli and Tiraboschi31 Protein-losing enteropathy affects up to 18% of patients who underwent Fontan. It commonly presents as peripheral oedema, diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, and pleural or pericardial effusion. Reference Goldberg, Dodds and Rychik32 The gold standard is a 24-hour level of alfa-1-antitrypsin which measures protein leak in the intestinal mucosa. Reference Florent, LʼHirondel and Desmazures33 It is reasonable to believe that inflammation plays a vital role in the development of protein-losing enteropathy. Thus, corticosteroids have been used in patients with protein-losing enteropathy with considerable success. Reference Rothman and Snyder34 Prednisone has been introduced as a potential therapy for patients with protein-losing enteropathy, especially post-Fontan operation. The suggested dosing regimen is 1–2 mg/kg/day orally. Alternatively, Budesonide has been used for this purpose as well. Reference Thacker, Patel and Dodds35,Reference John, Driscoll and Warnes36

Complications

The severity of the complications is determined by how fast the chylothorax accumulated, its size, and its chronicity. Some early complications of chylothorax loss include dehydration, hypoalbuminemia, respiratory distress, and a longer post-operative course. As chyle carries several nutrients and immunoglobulins, it is expected that complications from chylothorax, especially if long term, includes malnutrition, weight loss, muscle wasting, and immunodeficiency leading to susceptibility to infections. This increases both the risk of morbidity and mortality on the patient. Reference McGrath, Blades and Anderson37 Therefore, optimising the diet of these patients with proteins, electrolytes, and proper nutrients is essential. Additionally, the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin to maintain normal immunoglobulin G levels is important to avoid serious post-operative infections. Reference Orange, Geha and Bonilla38 This emphasises the need to treat chylothorax promptly including the early worthy consideration of steroids for a speedy recovery.

Conclusion

Our main aim was to shed the light on the possible potential benefit of Steroids in the management of Chylothorax in the pediatric population following cardiothoraci surgery. Our patient was managed successfully with Prednisone, hence avoiding surgical intervention. There is no doubt that additional studies are required to establish the role and effectiveness of steroids in the treatment of chylothorax post-cardiac surgeries. We hope that this literature review would encourage further research to demonstrate the role of steroids in the management of chylothorax.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association relevant guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional review board (IRB)