Apromenade lesson is when the learners get up and source, identify and evaluate information from materials attached to the walls of the classroom or a corridor or some other space in the school. The students have to walk around the ‘exhibits’ to find out something and note it down as they go. This activity can forms a part of a sequence of tasks in a lesson. It works well for any subject matter which is highly visual, such as images taken from Pompeian wall-paintings, for example, or even for enlarged text selections.

The class I worked with numbered some 32 Year 7 students, mixed attainment, both boys and girls. They are in the first weeks of studying Latin through the CLC. In fact as I teach five of these classes, I had to teach the same thing five times: the lesson had to be reliable enough to work each time!

In this case I wanted to avoid a lesson devoted to propositional knowledge where the teacher or the book ‘downloads’ information, pre-digested. Instead, I wanted the pupils to engage more fully with the process of thinking about ‘how we know’ rather than just ‘what we know’. And I wanted the students to feel more engaged with the topic: by getting them to ask their own questions, I hoped that they would invest more energy and enthusiasm and learn more deeply.

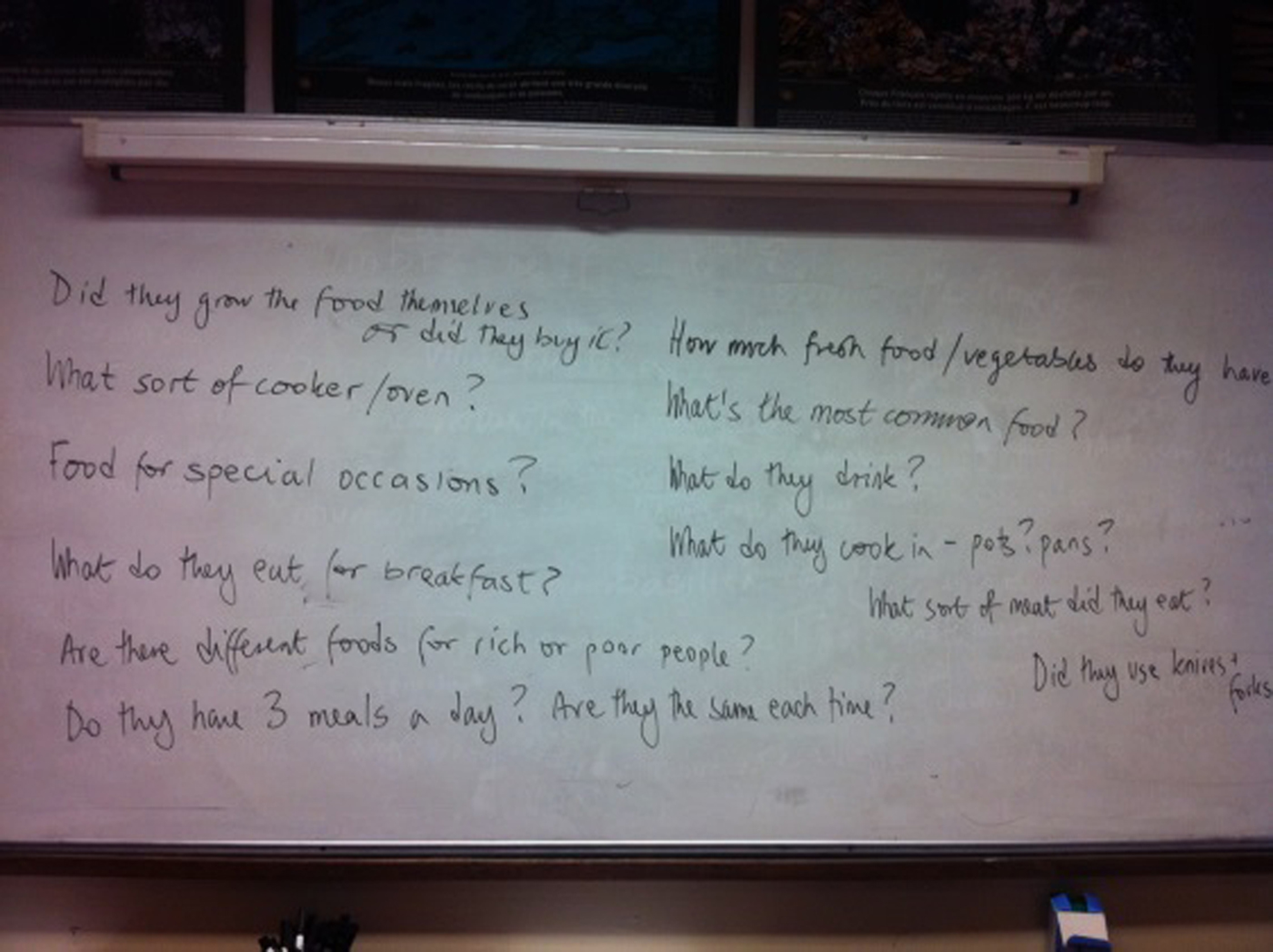

First of all I explained to the class that we were going to be archaeologists who were going to be finding out about Roman food and dining customs. I named us ‘The Food Detectives’. As a starting point I asked what questions the pupil / archaeologists might ask. As the pupils responded with their suggestions, I wrote them on the whiteboard, grouping some of the questions together, and getting pupils to elaborate or specify what they were asking where they were less coherent. It's important for the teacher to model the use of language at this stage, rather than just allow the pupils totally free rein. Thus, when a student seemed to be groping for the right word, I could open it out to the class to ask for suggestions of ‘good ways to describe this’ or could supply something of my own. The responses, as you can see, were very varied, ranging from the quite simple (‘Did they eat meat?’) to the much more thoughtful. One of the most interesting questions in the last few years came from a student who wanted to know if the fertility of the land in Campania was sufficient to support the local corn supply. The point about this part of the lesson is that it enables students of all abilities to have an input into the lesson and this then means they have put an investment into learning the outcome. Ideally those who ask the more simplistic questions will be exposed to the more sophisticated ones which will serve to develop their thinking. Having the questions on the board focuses attention for all and serves as a useful place for the classroom ‘collective memory’: it's nothing more than a gigantic worksheet – but one which they have created for themselves. Inevitably there are one or two students who ask questions which are silly, or which unintentionally divert attention away from what the teacher has in mind: the experienced teacher will have ways to bat these aside politely and refocus their attentions appropriately.

The questions which the pupils produced (see Figure 1) are listed below:

-

• Did they grow the food themselves – or did they buy it?

-

• What sort of cooker / oven did they have – if any?

-

• Were there different types of food for special occasions?

-

• What do they eat for breakfast?

-

• Do they have three meals a day? If so, do they eat different things?

-

• Do rich and poor people eat different things?

-

• How much fresh food and vegetables do they eat?

-

• What were the most common foods?

-

• What did they drink?

-

• What did they cook in – pots and pans?

-

• What sort of meat did they eat?

-

• Did they use knives and forks?

Figure 1. Students’ initial questions on the whiteboard.

Next I asked the pupils to go around the room in pairs looking at the laminated images which I had blu-tacked on the walls at child height. I explained before they went that these were primary source information and ensured that they knew what that meant. They had 15–20 minutes to collect information from around 25 pictures, and they needed to make notes in their exercise books. I thought originally of providing the students with a pre-printed sheet of categories - types of food and drink, cooking, dining habits, and so on – but decided that the students could instead make their own notes on a blank page. This would mean that the follow-up discussion would become more than just a verbal reiteration of what they had just found out, and instead would serve to develop their understanding further when we tried to categorise our findings. The students eagerly went off in pairs or threes to discover the answers to the very questions they had collectively devised and there was a contented buzz as they collaborated on interpreting the images (see Figure 2). Some of the images I had chosen were relatively simple: images of foodstuffs, such as fish or bowls of vegetables. Others I had deliberately chosen to be ambiguous and to cause discussion among the students: a picture of a cat in the larder was variously interpreted to suggest that the Romans might have eaten them; a picture of a loaf of bread was inevitably thought to be an early pizza. But the point was to provide the students with an opportunity to talk to each other about something which was a little beyond their experience, but not too much. None of it required prior knowledge; a lot of it required close observation, inference and a certain amount of guesswork. I wanted to achieve two things: students learning from each other by listening and comparing ideas; and students coming back with more questions which they wanted to think of answers to.

Figure 2. Students collaborate as they interpret the pictures.

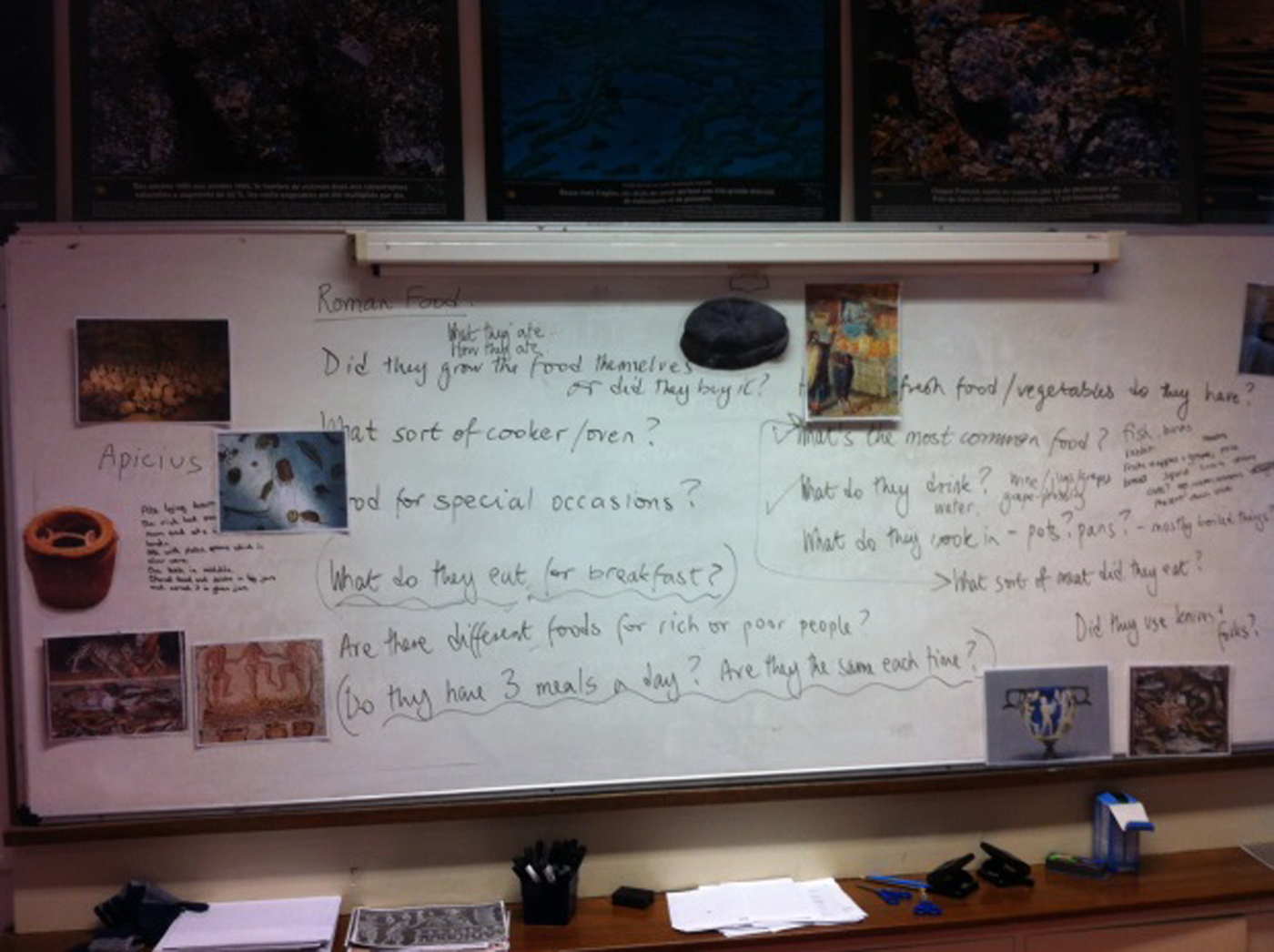

After the pupils had gathered information they returned to their seats and I asked some individuals what information they had found. After modelling this process, I got the most disruptive boy in the class to ask the questions and annotate the answers on the board – that kept him engaged and the pupils were happy to answer him as much as they had been happy to answer me!

During the feedback, I made sure that students started to sort out the information which they had gathered, through use of questioning and pulling students’ responses together. Who had something else which fitted into this category? Did anyone have another category? What category might we have for this? There were, of course, several objects which were difficult to categorise – a deliberate ploy, to ensure that the discussion did not falter. Throughout this part of the sequence of activities, I was consistent with the terminology that I wanted the students to use, focusing especially on subject - specific vocabulary and also on the way in which we talk about what we know and what we can tell. Teaching students to be able to say, ‘This implies that….’ Or ‘We can infer that….’ Or ‘This is possibly…’ is to my mind as important as teaching them to say, ‘That's an amphora’ or ‘in culina’. I'm as much interested in the how as the what.

While they gave their feedback, I elaborated a few of the points which had arisen. For example, I had especially chosen some photographs which illustrated particular things which I wanted to bring out. The issue of what the Romans ate from was well-illustrated by a picture of the Mildenhall Treasure – a local find and probably very untypical of what Romans ate from, except the most wealthy. I'm fully aware that this was not found in Pompeii and admit it to the students. But it serves a particular purpose for me. The students were fascinated by the discovery of the hoard in the 1940s, its subsequent purchase by the British Museum and the concept of treasure trove. In this case also I wanted to point out that the piece of evidence here did not prove either way that the Romans used knives or forks: the partiality of the evidence was an important concept I wanted to get across. So the Mildenhall Treasure served a dual purpose: a strong local story provided a memorable moment on which to attach more abstract ideas. I also had a picture of the loaf of bread from Pompeii and the wall-painting of the bread-salesman. Using these pieces of evidence, we talked about what may have been the staple diet of most of the Roman poor. Again, an archaeological mystery story – invented by myself – of how the loaf of bread was left behind in the oven (at Regulo 7!) when the baker ran for his life, only to be found by archaeologists nearly 2000 years later. This spiced up the story and acted as another memorable moment which delivered an abstract learning objective: this time, the idea of the communal oven and the bread dole.

At the end of this section of the lesson sequence, we noted which of the questions on the whiteboard we had been unable to answer and discussed why. I asked where we might find evidence to help answer some of the question, to which the (to this teacher anyway) rewarding answer came back: ‘That's why we need to learn the language.’

Next we watched the CLC Stage 2 DVD video documentary of Grumio in the Kitchen. We watched this twice – partly because I like the humour and it always delights me when I see the students pick up on them it – and partly because there is a lot of information contained in a short space of time. It always amazes me how quickly the students pick up on the information – and the sighs of happy laughter which greet the tinfoil peacock somehow always seem to be evidence of the students laughing with the documentary rather than at it. The CLC's ability in this way to engage and entertain seems to me to be unmatched in language courses: the students were enrapt (see Figure 3). There followed a discussion on the types of food which they recalled with amazing accuracy. As usual they picked up on the Romans’ use of spices, especially pepper in pretty much everything, and we also discussed what garum was. I also showed them the picture of the dormouse-fattening jar (which had been one of the pictures I had previously blu-tacked on the wall), because Grumio makes a fleeting reference to dormice. I got the students to try to guess what the object was (‘Grumio's mentioned it’), describe its form, and then, comparing it to a convenient waste paper bin nearby, pulled out a toy stuffed dormouse which I had previously secreted there. I make no excuses for another one of those memorable moments. After a second viewing of the video, the discussion focused more deeply on the ingredients which Grumio used which seemed surprising to the students, and which ingredients which are in common use today he did not mention at all. It is possible to elicit that he did not mention sugar, chocolate, tomatoes, potatoes and the students were asked to suggest reasons for this. The discussion extended and consolidated students’ knowledge of the extent of the Roman world and their dependence on trade for luxury goods.

Figure 3. Students watch the CLC video ‘Grumio in the kitchen’.

Figure 4. Further annotations on the whoteboard and highlighting of particular sources which deliver deeper learning objectives.

Finally, with us all having heavily annotated the whiteboard, the students were asked to write two to three paragraphs or equivalent in their exercise books on what they have learnt about Roman food and dining habits. They were given a choice of formats: a simple report, an invitation to a Roman dinner party or a Roman-style menu. As an extension, some pupils were asked to reflect on whether they thought the Roman diet was a healthy one or not and give reasons.