Otitis externa is the inflammation of the external auditory canal. It is a common problem in general practice [Reference Rowlands1]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are common pathogens in otitis externa [Reference Jayakar, Sanders and Jones2, Reference Ninkovic, Dullo and Saunders3].

Otitis externa displays a characteristic seasonal variation with a greater disease burden in warmer months [Reference Rowlands1, Reference Agius, Pickles and Burch4]. However, this seasonal variation in disease incidence has not been correlated to seasonal trends in the proportional incidence of pathogen isolates. In this retrospective, observational study, we show a seasonal variation in the proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa isolates in otitis externa and correlate the observed variation to changes in environmental conditions.

After institutional ethical approval, records of patients with the diagnosis of otitis externa on the sample request forms from January 2006 to December 2016 at Mid Essex Hospitals NHS Trust were analysed. Isolates were obtained from ear swabs cultured on agar following the standard operational procedure for ear swabs; based on the UK standards for microbiology investigations [5]. The proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa was the ratio of culture-positive patients with P. aeruginosa to the total number of patients with any other species isolate. Peak incidence date was estimated using Edward's method [Reference Edwards6]. Environmental data for the study period was obtained from the UK Meterological Office. The number of rainy days was correlated with the number of P. aeruginosa isolates. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0.

In the 9-year study period, 7770 patients had a positive bacterial culture. The commonest isolate was P. aeruginosa (n = 2802, proportional incidence 36%), followed by S. aureus (n = 1850, 24%), Aspergillus and Candida sp. (n = 1410, 18%), Enterobacteriaceae (n = 1289, 17%), anaerobic bacteria (n = 1212, 16%), beta-haemolytic streptococci (n = 811, 10%) and the Haemophilus, Streptococus pneumoniae, Moraxella group (n = 610, 8%). More than one organism was isolated from 3014 patients (39%).

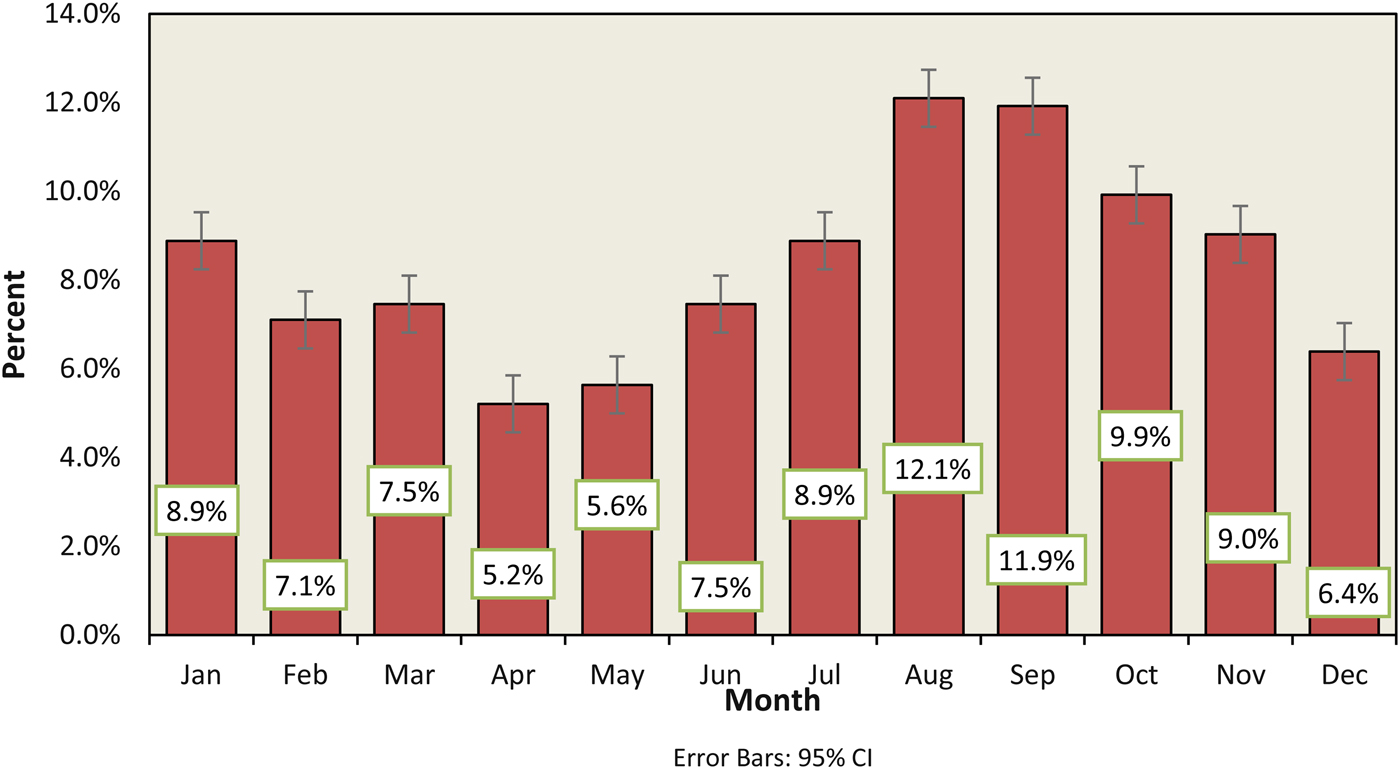

The average proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa was 25.9% (95% CI 25.0–26.9). However, there was a clear seasonal trend every year with a peak during the months of August–November (Fig. 1). No seasonal variation was evident for the other species isolates.

Fig. 1. Monthly incidence of P. aeruginosa in otitis externa infection from 2008 to 2016.

The proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa also showed age-related differences, with the greatest incidence in the 45–65 age group (25%), followed by over 65 and the 5 to 15 age groups (19% and 18% respectively). The seasonal variation in proportional incidence was clearly observed in 5–15 age group with peaks in August and September (21% and 14% respectively, compared with a yearly average of 8% (95 CI 7.1–9.6)).

The number of P. aeruginosa isolates each month correlated with the number of rainy days (r = 0.7). However, there was no correlation between the total number of patients with otitis externa and environmental factors (r = 0.2).

The relationship between diseases and seasons have been recognised since antiquity, with Hippocrates postulating changes in environmental factors such as air, water and food as explanatory causes [Reference Fisman7]. Our observational study confirms previously documented increases in otitis externa infections during summer months and the relative contributions of different agents to this incidence [Reference Rowlands1–Reference Agius, Pickles and Burch4]. We have, for the first time, identified P. aeruginosa as a possible causal agent for the seasonal variation in otitis externa. This seasonal variation in the proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa occurs mainly in the 5–15 age group and correlated with the number of rainy days. These associations have only been sparsely described in the literature [Reference Rowlands1, Reference Roland and Stroman8]. Neither the seasonal variation nor the environmental association was observed with other putative pathogens.

Predisposing factors for otitis externa include the presence of moisture, long exposure to moisture with an increased risk of maceration and cerumen loss, contact with contaminated water and increased water temperatures that promote rapid growth of the organism [Reference Wang9, Reference Lieberthal10]. These factors provide a clear causal mechanism for the observed association between the proportional incidence of P. aeruginosa and the number of rainy days. The seasonal variation in the 5–15 age group can be explained by behavioural changes leading to increased exposure to water in the warm summer months.

The associations described in the study have practical relevance in choosing empirical antibiotics for otitis externa, especially in younger patients in late summer months. In the absence of a bacterial culture, empirical treatment targeting P. aeruginosa and S. aureus would cover approximately 60% of the isolates in otitis externa.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.