Providing patient information has become increasingly recognised as an important part of clinical practice. Without it, informed choice about treatments is not possible. Unfortunately, much patient information is written in complex language and is poorly presented. Reference Coulter, Ellins, Swain, Clarke, Heron and Rasul1

In an attempt to improve patient information, the Department of Health recently established the Information Standard quality mark (www.theinformationstandard.org). This mark signposts trustworthy information. It is awarded to organisations after assessing their editorial and review processes, and comparing a small sample of their leaflets against a modified 29-item version of the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Instrument checklist. Reference Elwyn, O'Connor, Stacey, Volk, Edwards and Coulter2 The Royal College of Psychiatrists was involved in the pilot phase of this project and received its accreditation in 2009.

The College website (www.rcpsych.ac.uk) has hosted patient information resources for over 10 years. The website has become a leading source of public mental health information in the UK. We know this because the leaflets are ranked highly by Google, the most popular search engine in the UK. A search of mental health keywords such as ‘depression’, ‘anorexia’ and ‘schizophrenia’ returns the leaflets in the top five search results. In addition, at the time of writing, the website is ranked higher in terms of popularity than many of the leading main mental health charity websites in the UK, including Mind, Sane, Rethink, Depression Alliance and the Mental Health Foundation (www.alexa.com).

The public information section currently has 113 mental health information leaflets, with over 150 translations into Arabic, Bengali, Persian, Urdu, Chinese, Hindi, Greek, Spanish, French, Russian, Polish, Gujarati, Punjabi and Welsh. The 113 leaflets are divided into four categories:

-

• Help is at Hand leaflets, which contain up to 12 pages of in-depth information about mental health conditions;

-

• Keyfacts leaflets, which are briefer, two-page overviews of the same conditions;

-

• Changing Minds leaflets, which are designed to challenge stigma;

-

• Mental Health and Growing Up (MHGU) leaflets, which cover mental health problems in young people.

The College produced paper leaflets for over 10 years before the website was developed, but it had difficulty evaluating the leaflets and gathering feedback. The website provided an opportunity to find out what our readers thought of the leaflets and to collate feedback to guide their further development. Against this background, this paper reviews the feedback received from our readers between 1 September 2008 and 31 October 2009.

Method

Readers are offered the opportunity to complete a feedback form at the end of each leaflet. There are three parts to the form:

-

• information about the reader

-

• free-text comments

-

• a five-point scale to rate the readability, usefulness, respectfulness and design of the leaflet (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Example of feedback form.

The feedback forms are emailed to the College and the results automatically collated and stored in a database.

Results

Website visits

During the period under analysis there were 3 378 000 visits to the College website by 2 247 000 people from more than 222 countries. The highest visiting countries can be seen in Table 1. The country of origin could not be identified for 20 000 visitors (approximately 0.5%).

Table 1 Website visits by country of origin

| Country | Visits, n | % of total visits |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 2 500 000 | 73 |

| USA | 257 000 | 7 |

| Canada | 80 000 | 2 |

| Ireland | 80 000 | 2 |

| Australia | 77 000 | 2 |

| India | 30 000 | 1 |

| Iran | 24 000 | 0.5 |

| Other (including unknown) | 330 000 | 12.5 |

On average each visitor looked at three pages on the website, resulting in about 10 million page views. The public information section is the most popular area of the website, accounting for about 40% of these visits.

Feedback forms

We received 37 800 feedback forms - approximately one form for every 80 visitors to a leaflet. Forms that were completed only partially were excluded from the analysis. Leaflets with fewer than 20 completed feedback forms were excluded to ensure that average scores for each leaflet were based on a significant number of responses. We also excluded feedback on foreign-language leaflets.

Table 2 shows the overall number of leaflets in each category; the number of leaflets with 20 or more replies included in the analysis; the number of feedback forms received in each category; and the number of complete feedback forms included in the analysis. The final column gives the overall average leaflet score for each category. This is calculated by averaging the scores for the four modalities (readable, useful, respectful, well-designed) in the feedback form. The modalities are measured on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest).

Table 2 Numbers of responses and feedback scores for each leaflet category

| Leaflet category | Leaflets, n | Leaflets included in analysis, n | Feedback forms received, n | Feedback forms included in analysis, n | Average score (out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | 52 | 51 | 26 355 | 17 797 | 4.55 |

| Keyfacts | 16 | 13 | 1830 | 1222 | 4.54 |

| Changing Minds | 7 | 7 | 1968 | 1546 | 4.48 |

| Mental Health and Growing Up | 38 | 33 | 3943 | 2237 | 4.38 |

These figures show that the main leaflets are by far the most popular. This is probably because they are ranked very highly on Google. During the period under analysis, the most popular leaflet was on cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), attracting over 385 000 readers. During this time, Google ranked this leaflet in first place on a search for ‘CBT’ or ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’. The second most popular leaflet was on antidepressants, which was also ranked in first place by Google.

The overall average scores for each leaflet category are high (4.38-4.55 out of a maximum of 5), suggesting that the leaflets are well received.

Demographics

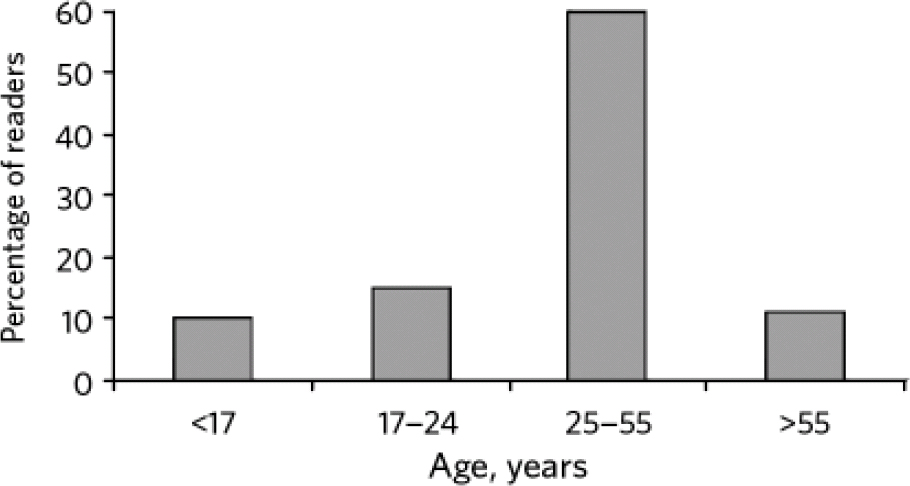

The age breakdown of the people submitting feedback forms can be seen inFig. 2 (4% of responders did not indicate their age). As might be expected, the MHGU leaflets attract young readers: 20% are aged 16 years or under. The Changing Minds leaflets also attract young readers: 28% are aged 16 years or younger and 29% are aged 17-24 years. This could be because the leaflets are short and written in a direct and provocative style.

Fig 2 Age of readers.

Overall, 25-38% of readers describe themselves as patients, about 15% as health professionals and 15% as students. The remainder are carers, relatives or friends of a patient.

Individual leaflets

To measure the popularity of individual leaflets within the four categories, we ranked each leaflet according to its average score.Table 3 shows the results for the four highest scoring and four lowest scoring leaflets.

Table 3 Average scores for highest and lowest performing leaflets

| Leaflet | Leaflet category | Feedback forms, n | Mean leaflet score (mean category score) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest scoring | Post-traumatic stress disorder | Main | 1108 | 4.75 (4.55) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Main | 287 | 4.75 (4.55) | |

| Bipolar disorder | Keyfacts | 115 | 4.74 (4.54) | |

| Physical activity | Main | 136 | 4.73 (4.55) | |

| Lowest scoring | Anorexia and bulimia | Changing Minds | 968 | 4.03 (4.48) |

| Alcohol and depression | Main | 280 | 3.72 (4.55) | |

| Drugs and alcohol | Mental Health and Growing Up | 58 | 3.72 (4.38) |

The lowest scoring leaflets are about issues that attract controversy in the public domain. This controversy may partly account for their higher than average share of negative free-text feedback, as described in the next section. The low scores encouraged us to revisit these titles to see whether we can improve them.

Analysis of free-text feedback

We also undertook a simple qualitative analysis of the free-text responses for a number of leaflets. For the purposes of this paper, we focused on the two highest scoring main leaflets (‘post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)’ and ‘obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)’) and the two lowest scoring main leaflets (‘Cannabis and mental health’ and ‘Alcohol and depression’). For the highest scoring leaflets, 54% provided a simple commendation such as ‘great leaflet’; 33% provided some autobiographical information about their problem; 7% asked a question; 6% gave a constructive suggestion; 4% said they intended to use the leaflet in their work; and about 2.5% left a negative or abusive comment. The lowest scoring leaflets were just as likely as the highest scoring leaflets to receive commendations but more than twice as likely to receive a negative comment (6% v. 2.5%).

The constructive criticisms are particularly useful in helping us to identify specific ways in which to improve the leaflets (Box 1).

Discussion

The introduction of the Information Standard quality mark should lead to an improvement in the reliability of patient information among participating organisations. However, it does not necessarily follow that leaflets conforming to this standard will be well received by the public. The only way to assess the reception of a leaflet is to ask the readership.

The quantitative feedback enables us to rank the leaflets and to determine which leaflets need more attention. The qualitative feedback provides constructive advice, suggestions and challenges that help us to identify specific areas for rewriting or fine-tuning. Because the Spearman's correlation between the modalities on the feedback form is high (0.72-0.96), we could simplify the form and use a single score, such as the five-star rating system used by Amazon.com. In the future we would like to display this rating alongside the leaflets so that readers can see at a glance how previous readers have rated them.

Our current findings suggest that reader feedback provides invaluable guidance about the substance and presentation of our public mental health information. This feedback complements the Information Standard quality mark, which is focused mainly on editorial, review and production processes.

Box 1 Examples of commendation, constructive and negative responses

Alcohol and depression leaflet

-

• Commendation: ‘I strongly agree with everything you have commented on and have taken many points into consideration. I really hope I can learn from this leaflet.’

-

• Constructive: ‘My only criticism of your leaflet is that it does not address the social pressure to drink which is ingrained in British culture. I'd love to go out for “a” drink but in practice I end up drinking up to 8 units in one sitting.’

-

• Constructive: ‘Could use some pictures for a friendlier feel.’

-

• Negative: ‘This information is appauling (sic) and of terrible quality. Alcoholics know what is wrong and why they need SOLUTIONS.’

Cannabis and mental health leaflet

-

• Commendation: ‘This was really really useful and opened my eyes to a lot of things I didn't realise.’

-

• Constructive: ‘More subheadings would be useful for young people - perhaps even illustrations. It has quite a high reading age.’

-

• Constructive: ‘It would need to have more visual diagrams and probably less slang (which can quickly get out of date).’

-

• Negative: ‘Negative and typical of official sources.’

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.