Introduction

‘Rape, like genocide, will not be deterred unless and until the stories are heard. People must hear the horrifying, think the unthinkable and speak the unspeakable.’

(Tompkins, Reference Tompkins1995; p. 852)Is there a need for this article?

In preparation for writing this article, we consulted a group of high-intensity therapists (n=29) using an informal survey to gain an understanding of what they would like to know about treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following a rape in adulthood. Fifty-nine per cent of the respondents said that they did not feel confident about working with PTSD after rape and highlighted particular gaps in their knowledge. This article will address those gaps.

Given that the aim of this article is to increase therapist confidence in working with PTSD following rape, we will focus on how to treat more ‘straightforward’ presentations. At times, we will discuss how this might be different with multiple incidents and/or a history of prior trauma. However, we believe that therapists need to really understand how to treat PTSD following one rape or sexual assault before they can flex the model for complicated histories. For further guidance on working with complexity in CT-PTSD, please see Murray and El-Leithy (Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022).

This work can all be conducted remotely assuming it is via videocall, not telephone. Please refer to https://oxcadatresources.com/covid-19-resources/ and Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Kerr, Thew, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2020) for guidance regarding remote working. This can also all be done through an interpreter: please see d’Ardenne et al. (Reference d’Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007) and the following film link (https://vimeo.com/792166984/19f2122a2f) for further guidance.

Background information about rape and sexual assault

The prevalence of rape and sexual offences in the UK is reviewed regularly by the Office for National Statistics Crime Survey for England and Wales. Sexual offences in England and Wales were reported to be at their highest ever level in the year ending June 2022 (Office for National Statistics, 2022; 196,889 offences), with similar levels recorded in the most recent report (Office for National Statistics, 2023; 191,052 offences). Of the offences reported to police, 36% were rape offences (Office for National Statistics, 2023); however, it is important to remember that this does not reflect the number of sexual offences perpetrated overall. Estimates from the Crime Survey for England and Wales reveal that fewer than one in six survivors of sexual offences report these crimes to the police (Office for National Statistics, 2023). However, the significant increase in reported sexual offences in recent years, may represent a closing of the gap between the number of rapes committed and the number reported.

Rapes against female survivors are reportedly far more likely perpetrated by someone known to the victim (Office for National Statistics, 2021): the perpetrator was most frequently reported to be their partner or ex-partner (45%), followed by someone known to them (37%, including dates/friends/acquaintances but not family or partners). ‘Stranger rape’ was reported by 15% of female survivors, compared with 43% of male survivors.

Rape is also used as a form of torture and psychological warfare. In addition, forced migrants arriving into the UK are also vulnerable to sexual violence on their journey and after arrival (Pertek et al., Reference Pertek, Phillimore, Goodson, Stevens, Thomas, Hassan, Darkal, Taal and Altaweel2021).

Sexual assault and rape are associated with a greater prevalence of a range of psychological difficulties (Dworkin, Reference Dworkin2020), with rape having the strongest risk of PTSD compared with any other types of trauma (Dworkin, Reference Dworkin2020; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rose, Koenen, Karam, Stang, Stein, Heeringa, Hill, Liberzon and McLaughlin2014). Indeed, the UK’s Office for National Statistics (2021) also reported that 62.7% of rape survivors experienced consequent ‘mental or emotional problems’, and 10.1% attempted suicide after being raped. Dissociation during a trauma, which often occurs during rape, has also been significantly linked to more severe PTSD symptoms (DeMello et al., DeMello et al., Reference DeMello, Coimbra, Pedro, Benvenutti, Yeh, Mello, Mello and Poyares2023) and is a predictor of poor recovery from PTSD (Hagenaars and Hagenaars, Reference Hagenaars and Hagenaars2020). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of prospective studies reported that 74.58% of sexual assault survivors met diagnostic criteria for PTSD 1 month after the assault, and 41.5% after 1 year (Dworkin et al., Reference Dworkin, Jaffe, Bedard-Gilligan and Fitzpatrick2023).

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapies, such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye-movement desensitisation reprocessing (EMDR) have been found to reduce PTSD symptomology in rape survivors (O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Whelan, Carter, Brown, Tarzia, Hegarty, Feder and Brown2023; Regehr et al., Reference Regehr, Alaggia, Dennis, Pitts and Saini2013; Resick et al., Reference Resick, Williams, Suvak, Monson and Gradus2012).

Therapist fears/myths about working with sexual violence

The scale of sexual and interpersonal violence in the UK is a public health issue and, as a result, it is important that we have a workforce trained to be able to respond to people’s experiences of rape.

To work effectively with survivors of sexual violence, therapists also need to occupy a non-neutral human rights stance, which can sometimes feel uncomfortable. Therapists need to be clear that rape is a crime, and that it is recognised as such all around the world. It is always a crime, there are no mitigating factors (such as being drunk or withdrawing consent after some contact) that make it less of a crime. It is not ‘a difficult experience’ or ‘a misunderstanding’; it is a serious crime. We want to encourage therapists to embrace this stance as it could foster the kind of culture changes needed to ensure that rape survivors do not have to suffer further re-traumatisation when asking for care.

Discussing sexual violence is upsetting at the very least. Even experienced trauma therapists worry about and/or dread discussing rape with their clients. It is entirely understandable; peering into one of the darkest corners of human behaviour challenges so many dearly-held beliefs, such as those about safety and the benevolence of others. We know that we may leave our clinic with this information (and these images) swirling around our mind. However, this is often mitigated by the client’s relief of having shared their story and been heard and validated. In our clinical experience, the benefits greatly outweigh the costs. Survivors feel relief and gratitude when they are finally able to discuss the rape with someone who listens and validates their experience, while reminding them that they are now on the road to stopping flashing back to the memory.

Here we provide some suggestions about how to address common fears amongst therapists (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson2004; Purnell et al., Reference Purnell, Chiu, Bhutani, Grey, El-Leithy and Meiser-Stedman2024), and some encouragement about the positive benefits for clients of discussing rape and sexual violence.

-

It will make the client’s symptoms worse

Less experienced therapists also often fear that the discussion of sexual violence might retraumatise the client, or make their symptoms worse, or that it might be too shame-inducing for them to bear. It is true that beginning to discuss trauma can sometimes lead to a brief increase in the client’s intrusive symptoms of PTSD (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Stirman, Smith and Resick2016), whatever the nature of the trauma. This is because the client is no longer engaging in avoidance strategies. Yet, we know from decades of research that discussing trauma memories in detail is one of the most effective elements of treatment. Qualitative research found that rape survivors who received therapy considered trauma processing to be essential to their recovery, by helping them to form a coherent narrative of their experiences (Moor et al., Reference Moor, Otmazgin, Tsiddon and Mahazri2022). Indeed, patients interviewed after reliving often report that it is ‘worth the pain’ (Shearing et al., Reference Shearing, Lee and Clohessy2011; p. 466). Conversely, those with negative experiences of therapy after sexual assault noted therapists’ avoidance of discussing rape as a key factor (Starzynski et al., Reference Starzynski, Ullman and Vasquez2017). More participants in randomised controlled trials for PTSD experience a deterioration in symptoms in waitlist conditions than in trauma-focused treatments (e.g. Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert, Deale, Stott and Clark2014; Jayawickreme et al., Reference Jayawickreme, Cahill, Riggs, Rauch, Resick, Rothbaum and Foa2014). Similarly, rates of deterioration in patients over a course of CT-PTSD are very low and/or absent (e.g. 1.2% in Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale, Handley, Albert, Cullen and Hackmann2013; 0% in Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Duffy, Hackmann and Clark2002; for further review, see O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Whelan, Carter, Brown, Tarzia, Hegarty, Feder and Brown2023).

Clients need detailed psychoeducation about the aims and process of therapy, so that they have a clear rationale for why talking in detail about the rape will be helpful. This will then allow them to make an informed choice about engaging in the treatment and to actively ‘sign up’. This avoids any possibility of the client feeling coerced into proceeding and allows for open conversations about how to overcome challenges (e.g. how you will manage in sessions if the client is feeling avoidant of talking about their traumatic experiences). It is important to remember that the client is already experiencing flashbacks regularly. Addressing the trauma in therapy, in a structured and supportive environment, is unlikely to be any worse than what they already cope with. Discussing the trauma memories in detail also helps the client to realise that they can cope with having these memories and to not feel so controlled by them.

-

It will be too shame-inducing for the client

Strong feelings of shame are common following sexual violence and are linked to self-blame, fear of being judged by others, and feelings of humiliation. This may make it difficult for a survivor to disclose their experience (Bögner et al., Reference Bögner, Herlihy and Brewin2007). It may particularly be the case if the survivor is influenced by cultural ideas regarding gender and sexuality that contribute to a view of surviving rape as shameful (Bhuptani and Messman, Reference Bhuptani and Messman2023; Weiss, Reference Weiss2010). It is therefore important that you provide a compassionate, overtly non-judgemental and normalising space when the experience is disclosed. You may be the first person that the survivor has spoken to about their experience, and your reaction of warmth and acceptance could be an important first step in overcoming feelings of shame and fear linked to the rape.

Clients typically report that talking about their experiences of rape helps to reduce their feelings of shame and self-blame, rather than increasing them (Bhuptani and Messman, Reference Bhuptani and Messman2022). They learn that even though the therapist now knows exactly what happened to them, s/he still cares and is not disgusted or judgemental.

-

The therapist will not be able to cope

Talking about sexual violence is inherently challenging, not only for the client, but also for the therapist. It is important to talk to your supervisor about any concerns you have about how to manage in the session (or after it) and to create a plan for your own wellbeing if needed. Talking about sexual violence is rarely as difficult as the therapist (or client) anticipates. Make sure you talk with a supervisor about any areas you feel uncomfortable discussing. After the session, seek support or supervision as required; proactively making plans with a supervisor or colleague to check-in after a challenging session can help reduce feelings of isolation or helplessness. Most importantly, remind yourself that helping someone to stop re-experiencing a rape every day (in nightmares and flashbacks) is a great and worthwhile activity and that it was worth listening to some upsetting details in order to get there.

-

They might not want to work with me because of my gender

Occasionally, therapists are concerned about the impact of the gender of the therapist in working with sexual violence. In the authors’ experience, there are no clear rules about this. Sometimes a female rape survivor will only work with another woman, at other times, they have found it restorative to spend time with a compassionate male therapist. The same applies for male survivors. All we can suggest is that the therapist makes no assumptions about their clients’ preferences and asks them. Please see the following video of two male therapists who were interviewed about their experiences doing CT-PTSD for rape with female clients: https://vimeo.com/1037241866/9fdcfe4279?share=copy.

In addition to fears and myths about working with sexual violence, therapists may hold concerns or misconceptions about treating PTSD more generally using CBT. We encourage therapists to consult Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Grey, Warnock-Parkes, Kerr, Wild, Clark and Ehlers2022a) which helpfully discusses common misconceptions about CT-PTSD. For further discussion of myths about rape, please see the section below entitled ‘Rape myths and common gaslighting gambits’.

Service user perspective: a message to therapists from a survivor

We asked for feedback from a service user about their experience receiving CBT for rape. Below is the feedback we received:

‘I knew it was going to be unpleasant and it was. However, it was never as bad as I anticipated and I genuinely felt able to control the sessions and had a sense of agency with them. It felt empowering to have someone listen and work with me, we worked together on the problem. I didn’t have to try and solve it on my own anymore.

While discussing and practising the grounding techniques beforehand at times felt a little awkward, having my therapist do them with me was really helpful. The psycho-ed about dissociation was game-changing, it helped me to feel less freaked out by it and less to blame for not fighting back.

When it all came down to it though, it was the memory and imagery sessions that really made the difference. For some things the techniques worked the first time, and for others it didn’t. One of the moments that really shifted things was working on self-blame and the thought that I had “let it happen”. I could see on a cognitive level that this wasn’t accurate and that I wouldn’t say these things to someone else. However, just updating the memory with these words didn’t seem to help – I didn’t really feel any different. We decided to use some imagery to add a bit more power to the update and it was really effective. I feel so much better now I have had the treatment – I am able to engage properly with life for the first time since it happened. Please do this memory-focused work with people so they can lead a normal life again.’

Assessment

In this section we provide an overview of how to assess for PTSD. For more information about assessment and formulation, please see Murray and El-Leithy (Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022). We continue to discuss assessment of individual components (e.g. dissociation, guilt, shame) in their relevant sections in this paper.

Things to consider

Survivors of rape can often feel conflicted about accessing mental health treatment. In particular, they tell us that they fear their therapist may blame them. This fear can be intensified if the survivor was drunk or had taken drugs when they were raped. The survivor may have had the experience of overt or covert blaming from friends, family, police or health services. It is therefore very important that in early sessions, therapists do not ask the survivor whether or not they were drunk or had taken drugs during the trauma. We suggest you wait until it comes up naturally: e.g. this information may come to light during reliving (e.g. gaps in the memory), or when assessing/formulating guilt or shame.

Is it PTSD?

Given that PTSD has a very particular treatment, it is important to be completely sure that a client’s difficulties are best characterised as PTSD. Trauma underlies many different mental health conditions, so we need to be sure that the trauma of rape really has resulted in PTSD and not some other condition.

The best way for a therapist to proceed is to check their client’s presentation against the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. We find the ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2019/2021) the most helpful in this regard. ICD-11 stipulates that a diagnosis of PTSD is met following ‘exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events’, where the patient also presents with three core symptom characteristics:

-

(1) Re-experiencing the traumatic event(s) in the present in the form of vivid intrusive memories, flashbacks (feeling that the event is happening again in the here and now, in any sensory modality) or nightmares. Re-experiencing symptoms are usually accompanied by strong or overwhelming emotions and strong physical sensations that replicate those experienced at the time of the trauma.

-

(2) Avoidance of thoughts and memories of the event; avoidance of activities, situations, or people reminiscent of the event.

-

(3) Persistent perceptions of heightened current threat, e.g. hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response. To meet a diagnosis of PTSD, symptoms should persist for several weeks and cause ‘significant impairment … in important areas of functioning’ (ibid).

Self-report scales can be useful as part of an assessment for PTSD, for example the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr2013) or the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ; Cloitre et al., Reference Cloitre, Shevlin, Brewin, Bisson, Roberts, Maercker, Karatzias and Hyland2018) which maps onto the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria. However, clinicians should never rely solely on self-report measures, but conduct a thorough clinical assessment to assess for PTSD.

Sometimes it helps to think about the idea of a multisensory film being ‘recorded’ by the brain during the trauma. When any part of this ‘recording’ intrudes into the person’s mind, either during the day or at night, then it is a re-experiencing symptom. Most frequently, these intrusions are in the form of visual mental images but can also occur in other sensory modalities (e.g. the sound of screaming, the physical impact of an assault, the smell of an assailant, the taste of blood) (Hackmann et al., Reference Hackmann, Ehlers, Speckens and Clark2004). Particular attention should be paid to whether there is a match between what we know of the patient’s re-experiencing symptoms and what happened during the traumatic event, as these unprocessed memories are the key feature of a PTSD diagnosis.

Special attention should also be paid to distinguishing re-experiencing symptoms from rumination. Although rumination is also common following traumatic experiences, it is not part of a PTSD diagnosis. Rumination can feel distressing and intrusive to patients, but there is a more voluntary aspect to this remembering; the client is asking themselves questions about the trauma (e.g. ‘Why did it happen to me?’, ‘What could I have done to stop it?’, ‘If only I had done x or y?’, ‘How can people behave like that?’) rather than re-experiencing the trauma as if it happening again. In PTSD, unprocessed trauma memories will intrude with more vividness and sense of ‘now-ness’ than normal memories; true re-experiencing symptoms will also bring about greater distress and physiological reactivity. Rumination, on the other hand, may provoke a more depressed or angry state of mind. Please see the following link for further resources and information about working with rumination, either alongside or separately from PTSD: https://oxcadatresources.com/rumination/

Even where there are re-experiencing symptoms, therapists should be mindful that these symptoms alone do not constitute PTSD and that the other components of the symptom profile (avoidance and hyperarousal) are present. It can be helpful to think of the re-experiencing symptoms in PTSD as being like boiling oil being poured into the survivor’s head against their will. As soon as they come to mind, the person will do everything in their power to push them out as soon as possible, because they ‘burn’. In addition, if the survivor knows that certain people, places or activities are likely to make the memories come into their head, they will avoid them as a matter of self-preservation. This graphic metaphor is based on how clients with PTSD have described to us how they react when they re-experience their trauma memories. If, on assessment, clients seem to be choosing to think about the trauma and not doing everything in their power to avoid the memories, then PTSD is not a likely diagnosis. For further discussion about assessing PTSD, see Young and Grey (Reference Young, Grey and Corrie2016), and the training resources available for free at www.oxcadatresources.com.

So, assuming the rape survivor is suffering with PTSD, how should you go about treating them?

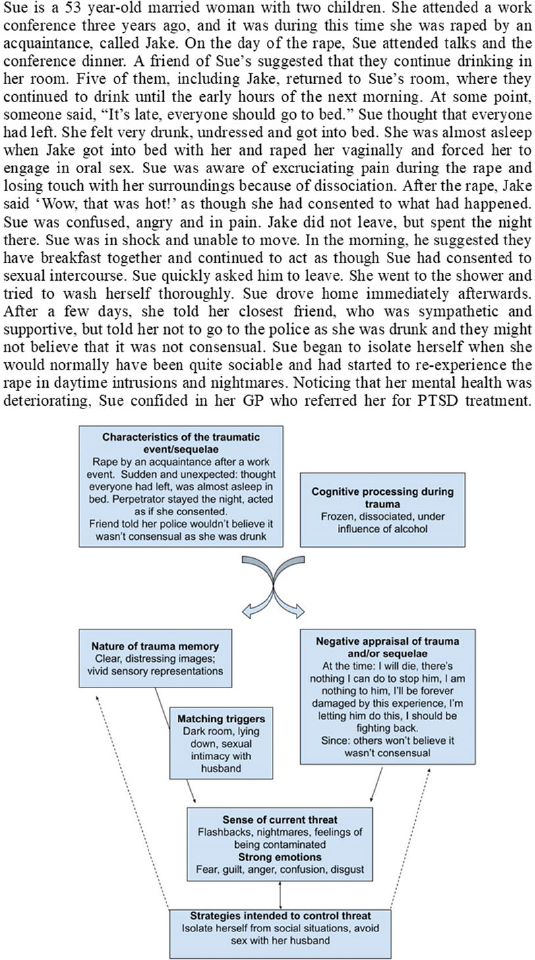

Ehlers and Clark model: summary and evidence

One of the evidence-based trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapies recommended as a first line treatment for PTSD is cognitive therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018). This treatment derives from Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model of PTSD (Fig. 1). This proposes that PTSD becomes persistent when traumatic information is processed in a way that leads to a sense of serious current threat. This can be a physical/external threat (e.g. ‘the world is a dangerous place’) and/or a psychological/internal threat to one’s view of oneself (e.g. ‘I’m weak’). Due to high levels of arousal at the time of the trauma, the trauma memory is poorly elaborated, fragmented and poorly integrated with other autobiographical memories and can be unintentionally triggered by a wide range of low-level cues. In particular, there is no ‘time-code’ on the memory that tells the individual that the event occurred in the past. Thus, when the memory intrudes, it feels as if the event is actually happening again to some degree.

Figure 1. Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) cognitive model of PTSD. Reprinted from Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319–345. Copyright with permission from Elsevier.

The persistence of the sense of current threat, and hence PTSD, arises from not only the nature of the trauma memory but also the negative interpretations of the symptoms experienced (e.g. ‘I’m going mad’), the event itself (e.g. ‘It’s my fault’) and sequelae (e.g. ‘I should have got over it by now’; ‘Others don’t care about me’). Change in these meanings and the nature of the trauma memory is prevented by a variety of cognitive and behavioural strategies, such as avoiding thoughts, feelings, places or other reminders of the event, suppression of intrusive memories, rumination about certain aspects of the event or sequelae and other avoidant/numbing strategies such as alcohol and drug use.

The aims of CT-PTSD treatment are threefold:

-

(1) To reduce re-experiencing by elaboration of the trauma memory and discrimination of triggers, and integration of the memory within existing autobiographical memory.

-

(2) To address the negative appraisals/meanings associated with the event and its sequelae.

-

(3) To change the avoidant/numbing strategies that prevent processing of the memory and reassessment of meanings.

A wide range of both general and PTSD-specific cognitive behavioural interventions can be used to achieve such changes. There is significant evidence for the effectiveness of CT-PTSD from randomised controlled trials (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Gillespie and Clark2007; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell2005; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert, Deale, Stott and Clark2014; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Wild, Warnock-Parkes, Grey, Murray, Kerr, Rozental, Thew, Janecka and Beierl2023), studies in routine services (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale, Handley, Albert, Cullen and Hackmann2013; Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Duffy, Hackmann and Clark2002), for children and young people (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Yule, Perrin, Tranah, Dalgleish and Clark2007), and outside the UK (Bækkelund et al., Reference Bækkelund, Endsjø, Peters, Babaii and Egeland2022).

Generally, there is no need to share the whole formulation model with the client: given that the rate of PTSD is so high after rape, there is not such a big question as to why this person has PTSD in terms of their pre-morbid personality. It may be more appropriate to share microformulations or idiosyncratic formulations focusing on the parts most relevant to their symptoms.

It is also important to recognise that for the client the trauma might not be limited to the rape but might also concern the aftermath, e.g. responses from others, treatment by medical professionals, physical examinations, reporting to the police, legal trials, etc.

Treatment

To help bring our guidance to life, we will follow a case example throughout this article (Box 1). We will also provide links to some films demonstrating the techniques. These were made by the authors, in one take. Thus, they are not flawless but represent a ‘good enough’ attempt to show the reader how to approach each technique.

Box 1. Fictional case example, ‘Sue’ including how to understand her presentation within the Ehlers and Clark’s (2000) model of PTSD

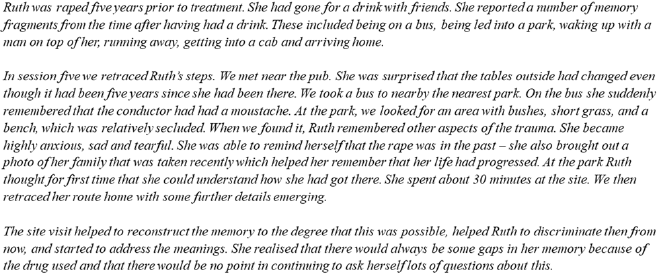

The treatment for ‘Sue’ is shown in the following sequence and is typical of the kinds of interventions needed for CT-PTSD to an adult rape. Figure 2 offers a rough outline for the order in which the key components/interventions may be used during CT-PTSD. If all things are equal, you can follow this rough order, but please deviate on the basis of your formulation if you think you should do something else first (e.g. doing now vs then thinking in order to attend sessions and/or as part of hotspot updates; site visits are often done at the end of therapy but may be needed earlier; rebuilding/reclaiming life tasks are conducted throughout the course of treatment). The trauma-focused work is the most important: do what you need to of the earlier phases but these are to make it possible to get to the work that is most going to help.

Figure 2. Flow chart summarising rough order of interventions within CT-PTSD. Purple boxes denote essential components of CT-PTSD; grey boxes denote additional techniques therapists may wish to employ.

Psychoeducation and generating a shared formulation of how PTSD has developed

CT-PTSD begins with psychoeducation to normalise symptoms (see a downloadable leaflet at www.oxcadatresources.com as well as a video of how to undertake an individualised case formulation in the first treatment session). The crux of the explanation of PTSD needs to address how the symptoms are understandable and that there is something that can be done to help. With PTSD following rape, it is also helpful to highlight that about 50% of all rape survivors develop these symptoms. Moreover, once the symptoms become established, they are unlikely to go away without a trauma-focused therapy.

Given that CT-PTSD will involve discussing the rape in some detail, providing a good rationale for trauma-focused treatment is crucial – you need your client to understand why it would ever be a good idea to talk about this terrible event in some detail. It is a paradoxical idea for many, so we recommend that you do not proceed to the rest of the treatment protocol until you are sure that the client has understood and ‘signed up’ to the rationale. This will also avoid therapists finding themselves in the deeply uncomfortable position of feeling that they are pushing a client to discuss the details of rape.

When discussing PTSD symptoms with survivors of rape, we have found that even psychoeducation may trigger flashbacks and intrusive memories of the traumatic event. This will greatly disrupt the client’s concentration and ability to take in the information. Using attention-grabbing visual aids can help in this regard and so enable retention. For example, one often-used explanation relates to memory being like a cupboard (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). The therapist might say, ‘Imagine that memory is a little bit like a linen cupboard. There are towels on one shelf, sheets on another and blankets and duvet covers down at the bottom. It is all organised. When you are involved in a trauma, it is as if someone runs at you with a huge duvet in their arms, screaming “PUT THAT IN THE CUPBOARD RIGHT NOW!”. You take the duvet, stuff it in, push the door shut and walk away. As you do so, the cupboard door opens and the duvet comes out. The person screams again: “PUT IT AWAY NOW!”. Every time you try to put it back in it comes back out again. This is what happens when you are involved in a traumatic event. The traumatic event is like the duvet, it is too big to fit into how you normally remember things (the cupboard). So you might put it out of your mind because it is upsetting (stuff the duvet in). However, this does not work. The memory keeps coming back, in nightmares or during the day in the form of intrusions or flashbacks.’

As the therapist explains this, it will help to use a real cupboard and a large duvet – the client will not forget your explanation. If this is not possible, a large piece of flip chart paper and a small cardboard box will suffice. Having pictures of this metaphor for clients to take home will also be very helpful. See https://vimeo.com/915199586/12c906f0a7?share=copy for a film running through this explanation that you can show to clients.

It can also help to invite the client to solve the problem of the overfull cupboard for you: ‘What would you do if you had this problem – how can we get the duvet to fit into the cupboard?’. The client will suggest re-organizing the cupboard a little and smoothing out the duvet on the floor, so that it can be folded up nicely. The therapist can then ask the client to try their solution, again, making the whole explanation more memorable. ‘Brilliant, yes, that is also what we will need to do in out sessions together, talk through what happened in a special way and work out together how to “smooth it out” with what we now know, and find ways of making it a little less distressing so that we can put it away, so that it stops coming into your mind when you don’t want it to.’

Given that PTSD following rape is so common (which is not the case after many other types of traumatic event), explanations can hint at the idea that PTSD following rape is almost inevitable. We have found that a simple brain and memory-based metaphor can work well and has the advantage of helping the client to feel that having PTSD following rape is simply a consequence of the enormity of the horror of their experience.

Please note that this explanation is a simplified version of a theory about what might be going on in the brain during traumatic events and should not be presented as biological or neurological ‘fact’. It is loosely based on ideas outlined in Brewin, Dalgleish & Joseph’s (Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996) dual representation theory of PTSD (see also Brewin, Reference Brewin2001).

Using Fig. 3 below, the therapist might say: ‘This is a simplification of something very complex. We think that memory is stored in two places in the brain. The first place is called the hippocampus. [Point to this area in the picture.] The hippocampus is where all our normal memories for events from our lives are stored. For example, things like your first day at school, birthday parties, weddings, winning a prize, first job. It is a bit like a filing cabinet. We can usually control whether we think about these memories or not, they have a “time stamp” that tells us they happened in the past and when they happened, and we can update these memories with new information.

Figure 3. Simplified illustration of relevant brain regions to accompany psychoeducation.

The second place in the brain where memories are stored is called the amygdala. [Point to this area in the picture]. The amygdala is a very different type of memory store to the hippocampus. This is our brain’s alarm system and, when faced with something we think is dangerous, the alarm goes off. It tells us we are in danger and need to do something or we will get hurt. It is a simple type of memory about whether we are in danger.

We know that during a traumatic event, the hippocampus stops working and so traumatic memories are stored mainly in the amygdala. The memories stored here are the opposite to memories in the hippocampus. We cannot control whether or not we think about them, they just automatically come into our minds without warning. They do not have a “time stamp” that tells us when they happened, so it can feel like the event is happening again right now; we don’t know it happened in the past. We cannot update these memories with new information, so we feel and think the same things we did during the traumatic event. It is like the memories are frozen in time.

After a traumatic event, the brain tries to manage what has happened and move the memories from the alarm system (the amygdala) to file them away neatly in the filing cabinet (the hippocampus). If that is not possible, the memories do not get stored away in the hippocampus, instead they remain stuck in the amygdala. This results in someone experiencing PTSD symptoms because their alarm system keeps going off and making them feel that they are in danger and the event is happening again, right now.

So, to help with PTSD symptoms we need to help you move the traumatic memories from the amygdala to the hippocampus, to give you more control over these memories. Now I am going to explain how to do that.’

Using the diagrams below, the therapist might then explain: ‘We see the memory of the rape as a bit like an electrical pulse, with a number of peaks, which represent the worst parts of the terrible experience – the most upsetting/frightening parts. As you can see in this picture [Fig. 4], the peaks are so high that the pulse (trauma memory) won’t “fit” into the hippocampus, the memory store where you can control whether or not you think about the memory’.

Figure 4. Diagram illustrating “peaks” of emotion (‘hotspots’ or worst moments) within the trauma memory.

‘What we need to do in therapy is carefully to talk through the rape to identify the peaks of emotion, the worst parts, so that we can work together, to “shrink” them down enough so that they now “fit into” the correct memory store’ (Fig. 5). ‘Once there, you will be able to control whether or not you think about the event.’

Figure 5. Illustration of the aim to reduce the strength with which emotions during hotspots are experienced when the memory is activated.

Reclaiming and rebuilding life

Reclaiming and rebuilding life is a core part of CT-PTSD. The aim is to help the client, right from the early sessions, to start to take back control of some parts of their life, however small. We suggest looking at a comprehensive role play demonstration at www.oxcadatresources.com for more information.

Stabilisation

Some clients may require some psychoeducation about emotions and strategies to help regulate their emotions prior to engaging in the trauma-focused work. This can be integrated into CT-PTSD treatment, for example helping clients understand maintenance cycles between anxiety and avoidance. Some of the strategies we discuss below (e.g. grounding) can be used to help regulate emotions. However, some clients with more complex histories (e.g. childhood abuse or neglect) may require further work to develop emotion regulation skills, which may be needed prior to engaging in CT-PTSD, and can be implemented as part of a phased treatment model. It should be noted that not everyone with a complex history requires this type of intervention (de Jongh et al., Reference De Jong, Resick, Zoeliner, Van Minnen, Lee, Monson, Foa, Wheeler, Broeke, Feeny, Rauch, Chard, Mueser, Sloan, Van Der Gaag, Rothbaum, Neuner, De Roos, Hehenkamp, Rosner and Bicanic2016; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Grey, Warnock-Parkes, Kerr, Wild, Clark and Ehlers2022a) and this should be assessed on an individual basis.

For examples of such interventions and further information, please see:

-

Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR; see Cloitre et al., Reference Cloitre, Cohen, Ortigo, Jackson and Koenen2020)

-

Compassion focused therapy to reduce shame/self-blame (see Lee and James, Reference Lee and James2012)

-

NHS self-help guide (https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/mental-health/mental-health-self-help-guides/ptsd-and-cptsd-self-help-guide/)

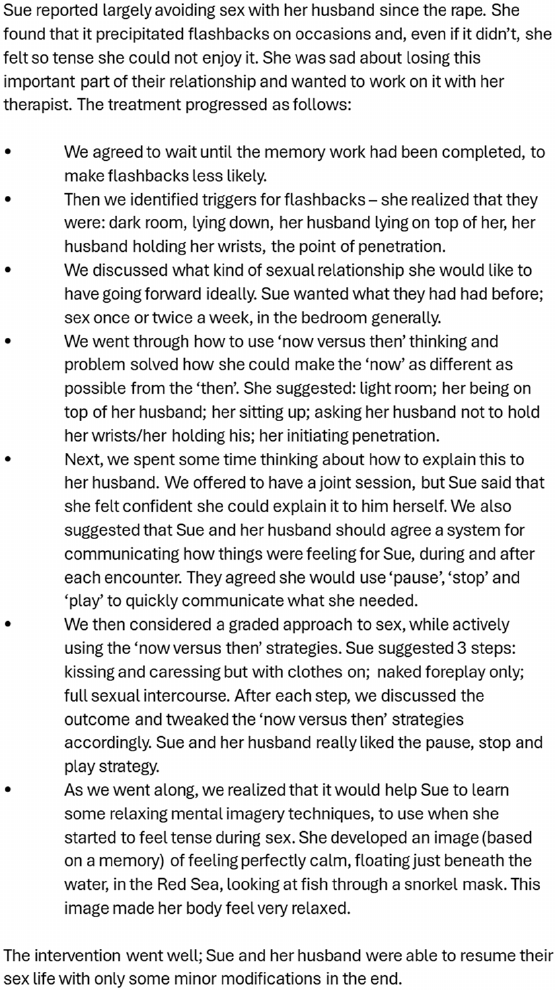

Managing dissociation

Dissociation is a discontinuity in the way behaviour, memory, identity, consciousness, emotion, perception, body representation, or motor control are usually integrated (DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Peri-traumatic dissociation (i.e. dissociation at the time of the trauma) disrupts memory encoding (Brewin, Reference Brewin2001; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) and, as mentioned earlier, has been identified as a strong predictive factor for the development of PTSD (Birmes et al., Reference Birmes, Brunet, Carreras, Ducassé, Charlet, Lauque, Sztulman and Schmitt2003; Breh and Seidler, Reference Breh and Seidler2007; Ozer et al., Reference Ozer, Best, Lipsey and Weiss2003). In the authors’ experience, almost all clients with PTSD to rape automatically dissociate during the event. As such, it is essential to discuss and prepare for dissociation in trauma-focused therapy for rape survivors (see Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019).

Providing psychoeducation and normalising dissociation is hugely important. We have found Schauer and Elbert’s (Reference Schauer and Elbert2010) ‘defence cascade’ evolutionary model of dissociation useful when discussing dissociation with clients. Please see Chessell et al. (Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019) for guidance on how to explain the model to clients, and this film for a role play demonstration of explaining it to Sue: https://vimeo.com/874562902/b2e9f2ecb3?share=copy.

This model, often referred to as the 6Fs, suggests that dissociation is an evolutionarily adaptive response to inescapable threat. Schauer and Elbert (Reference Schauer and Elbert2010) suggest extending the more commonly known ‘fight or flight’ response with the addition of ‘fright, flag, faint’ stages, which occur if the trauma is prolonged and/or inescapable (Fig. 6). They argue that if the client cannot escape the threatening situation, it is adaptive to stop struggling and to become still. Thus, outside of the client’s conscious control, if they cannot escape, they will automatically dissociate.

Figure 6. Adapted illustration of Schauer and Elbert’s (Reference Schauer and Elbert2010) ‘6Fs’ defence cascade model.

First, in the ‘fright’ stage, the client finds themselves unable to move or speak/scream, their anger is suppressed but they remain very frightened. This ‘shut-down’ response promotes preservation of life when a person faces an extreme threat, particularly when their body is penetrated, such as during rape. Not being able to struggle during rape may minimise further physical injury (both internally and externally), while not shouting at the rapist may mean they do not beat you unconscious or strangle you to keep you quiet. As dissociation progresses further, through the ‘flag and faint’ phases, the person’s blood pressure drops, they start not to feel pain, they lose contact with their body, their vision and hearing narrows, they can begin to feel cold and, sometimes, they faint. While fainting is unusual during most traumatic events, it is frequently seen during rape (Kalaf et al., Reference Kalaf, Coutinho, Vilete, Luz, Berger, Mendlowicz and Figueira2017).

Knowing that this response is automatic, present cross-culturally and happens to men and women, big and small, strong and weak can help address damaging peri- or post-traumatic appraisals, such as, ‘the rape was my fault because I did not move/shout/run away/fight back’. These appraisals can often lead to high levels of guilt and shame. For some clients, it may also be helpful to discuss that there is evidence to suggest that dissociative ‘shut-down’ might become a conditioned response in individuals who experience repeated traumatic events within a similar context (Adenauer et al., Reference Adenauer, Catani, Keil, Aichinger and Neuner2010; Bolles and Fanselow, Reference Bolles and Fanselow1980). Therefore, individuals who have experienced multiple traumatic events are more likely to rapidly dissociate during any additional traumas that they experience.

It is also important to explain that when someone is experiencing PTSD, they may re-experience flashbacks to the uproar phase of their trauma; memories filled with adrenaline, fear and bodily arousal. Alternatively, they may re-experience the phase where they could not move/talk, or the phase where they fainted. If someone re-experiences the dissociative phases of their trauma memory during therapy, they will stop talking, feel faint and even faint, just as they did at the time.

Clearly, dissociating at home will present the client with many problems, but if this happens in the street, it is also a threat to their safety. Similarly, talking to a therapist about their rape will make it very likely that the client will dissociate. Given that this invariably involves them stopping talking, therapists need to work with the client to manage this early on. Careful assessment of the pattern of each client’s personal experience of dissociation will lead on to developing the most effective strategies to manage this. The presence and severity of dissociation can also be assessed with the use of relevant measures, such as the Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D) (Schalinski et al., Reference Schalinski, Schauer and Elbert2015) and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) (Carlson and Putnam, Reference Carlson and Putnam1993). However, a shared formulation, based on the Schauer and Elbert’s (Reference Schauer and Elbert2010) model, tends to be most useful. This should include psychological theory but importantly also the client’s personal experiences, cultural beliefs, and spiritual beliefs that may influence their understanding of dissociation.

It is important to find a way of doing the trauma-focused work with clients, even if they dissociate severely, for two reasons: first, because trauma-focused therapies have been shown to decrease dissociation through processing the memory (e.g. Atchley and Bedford, Reference Atchley and Bedford2021; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Murphy and Smith2016; Vancappel et al., Reference Vancappel, Réveillère and El-Hage2022); and second, because research has shown therapy to be just as effective even when a client experiences dissociation (for a meta-analysis of multiple treatment approaches, see Hoeboer et al., Reference Hoeboer, De Kleine, Molendijk, Schoorl, Oprel, Mouthaan, Van der Does and Van Minnen2020). Techniques such as narrative writing can also be considered as an alternative to reliving when there is significant dissociation to identify the hotspots. Here, the client or therapist produces a written account of the trauma, from where they can then focus in on the worst moments. See the helpful films about this technique and when to use it at www.oxcadatresources.com.

Grounding

Therapist and client can then start to experiment with strategies to manage dissociation. A good starting point is to gather information about the client’s common triggers for dissociation, which can be identified by discussing a recent example, using a diary and/or observing a flashback in session. If possible, early warning signs that the client is going to dissociate are then identified, although these are often not clear. Following this, you can try out various grounding strategies to try to bring the client’s attention back to the present as strongly as possible when they dissociate. It may help to practise these with the client before starting reliving. This process can be explained using the metaphor of an arm wrestle between the past and the present (see Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019 for the explanation), whereby the present needs to win the arm wrestle with the past to prevent dissociation. We can use all five senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, smell), as well as body movements/positions: see Table 1 for grounding strategies most often used during treatment for PTSD to rape. In essence, most strategies reinforce the present, drawing the survivor’s attention to the ‘now’ and how it is different from ‘then’. Please see this film link of how such strategies were used to update a hotspot featuring forced oral sex for Sue: https://vimeo.com/874002913/b2f8ffa85d?share=copy

Table 1. Examples of grounding strategies useful after rape, utilising each of the senses

* These tastes and smells work particularly well as they stimulate the trigeminal nerve in the face, whose role is to alert us quickly to poisonous food, so stimulating this nerve works very fast to bring back the person to the present.

** During dissociation, blood flow decreases to the speech production area of the brain (Broca’s area). Encouraging clients to speak out loud reverses this, as does copying hand gestures.

If the survivor stops talking during sessions because they have flashed back to the ‘shutdown’ phase of dissociation, your grounding strategies might need to be more energetic. Alongside the multisensory suggestions in the table above, we find that raising blood pressure through vigorous movement works well. The shutdown phase of dissociation features a drop in blood pressure, so working against this from the start of the session can sometimes ‘head off’ the dissociation. The following work well to raise blood pressure while still allowing the client to engage in the session: applied tension; running/jumping on the spot; hand strengtheners; squeezing hand therapy putty; peddling on an exercise bike/hand cycle; or using a stepper machine/walking on and off a step. Obviously, you may be limited by the equipment you have in your clinic, but we recommend investing in a few small pieces of exercise equipment. You may not be able to get this equipment, in which case use what you can (e.g. you can ask people to stand up and move their legs). As dehydration can impair psychological and physiological function (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2007; Pross, Reference Pross2017), people who are dehydrated may be more likely to dissociate so encouraging patients to drink before and during the session may help.

If you are doing this work remotely by video, make sure you ask about grounding tools and get them to show you. Suggest the survivor makes use of what’s around them: anything in their environment with strong sensory components will do (e.g. hot water bottle, air fresheners). It is also worth checking that they are sitting somewhere soft (e.g. sofa or bed) so that they don’t injure themselves if they experience shutdown dissociation. For further guidance on working safely remotely, see Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Kerr, Thew, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2020).

A plan of grounding strategies should also be developed if a client commonly dissociates when waking following nightmares of the traumatic event(s). These should be tailored to their sleeping environment.

More focused stimulus discrimination (‘now vs then’) strategies can also be discussed to manage particular activities (e.g. new sexual relationships) or particular kinds of flashbacks (e.g. pain flashbacks). For further guidance on now vs then discrimination, please see the training video resources on the OxCADAT website (www.oxcadatresources.com).

Getting started and ‘talking about talking’

Before starting a reliving session where the details of a rape will be discussed, it is helpful to have an open conversation with the client about any concerns they have about discussing this issue. For example, talking about sex, sexuality, genitalia or rape may be particularly taboo in their country of origin or culture. At this point, it can also be helpful to agree the terminology you will use for various body parts (particularly so if you are working through an interpreter). Clients may understandably be reluctant to specify which parts of the body were touched or assaulted and may use euphemisms or otherwise be vague. Agree terms that both the client and therapist feel comfortable using when describing different body parts, maybe using a drawn outline of the body for reference. Remind the client why it is important to be as detailed and specific as possible (referencing the psychoeducation) and reiterate that they have nothing to be ashamed about in speaking about the reality of their experiences.

It can be useful to use a ‘lock and key’ metaphor to explain why so much detail is needed: ‘As we have discussed, we are going to try and update this terrible memory, to make it less upsetting and allow you to “process” it, so that it stops coming into your mind when you don’t want it to. In a way, the traumatic memory is like a lock and the updates we will use are like a key. Now, if you are making a key for a lock, the first thing you do is make a detailed mould of the lock. Only when you understand each nook and cranny of the lock, will you make a key that works well. If we want updates that work for your memory, we need to understand all of the details in that memory. So, we do need to go into lots of detail, but be aware that every little detail we find in the “mould” helps us to make a better key – we are not doing this for the sake of it, we are doing this to help you get this memory out of your mind. This is step number one in having control over this memory.’

Whilst naming the discomfort is helpful, it is important for the therapist to be proactive and manage their own avoidance in these discussions to ensure the client feels confident in your ability to tolerate and manage this potentially difficult conversation. Proactively demonstrate compassion for the client and encourage them to make eye contact with you, to remind them that you are present, and reinforce the message that they have nothing to feel ashamed about when recounting their experiences. As a therapist, there is a difficult balance you need to strike between being sensitive to how hard these conversations will be for the client without somehow communicating that they may be too much for them or too embarrassing, which would not be helpful. Please see the beginning of this film for a demonstration of both how to discuss the need for details (lock and key metaphor) and the terms that the client would like to use to describe what happened: https://vimeo.com/873645203/1e235037e0?share=copy

Reliving and identifying hotspots

In CT-PTSD, reliving the traumatic event is the first stage in identifying the ‘hotspots’, or worst moments, so that these can be targeted for updating. Hotspots are the moments that typically map on to the patient’s re-experiencing symptoms and are the most distressing or aversive parts of the event; the moments that the brain has not been able to ‘digest’ properly. For a more detailed discussion of reliving and identifying and updating a hotspot, see the excellent films and resources on the OxCADAT website (www.oxcadatresources.com).

During reliving, in order to accurately identify hotspots, we ask the client to narrate the entire event in the first person, present tense, starting a few minutes before the event began. Ideally, the client will close their eyes and bring to mind the memory of the event and essentially, walk you through it, like an audio description of a film. Before you start, establish with the client a safe end-point; the first time they felt a sense of safety and relief after the rape. This may be immediately after the event, or hours later, for example at home or in hospital. If it was later on, agree what the end-point will be and ask the patient to ‘fast forward’ to this safe moment after reliving the rape.

It is best to allow at least 90 minutes for this session, because running out of time is not ideal. When occasionally you do run out of time, the therapist can ask the client to ‘fast forward’ to the agreed end. It is worth reassuring the client that they can pause the reliving if they want to; in our experience, few clients take up this offer, but knowing that it is there is important for their sense of control over the reliving process.

The therapist will guide the client through the event to ensure the reliving account is slow and thorough, asking about information in all sensory modalities including cognitions and images: ‘What do you see now? What do you feel in your body? What sounds can you hear? What can you smell/taste? What is going through your mind – thoughts, images?’. If the therapist feels that the patient is avoiding parts of the memory, or skipping over parts, they can gently ask the patient to rewind the narrative to ensure all information is captured. If necessary, remind the client of why we need all the details (for the mould of our lock). A good rule of thumb for a therapist is that if you get an overwhelming urge not to ask a question, e.g. ‘What did it feel like when he penetrated you?’ or ‘What did the semen taste like?’, it is your cue that you should ask these questions. It may be fruitful to ask the client if there is anything they are avoiding saying or struggling to say, normalising and empathising with this and encouraging them to go towards it if possible.

It will be clear if the client is truly connecting with the traumatic memory as they will become physiologically aroused and distressed in the reliving. At the end of the account, arrive at the agreed safe point; allow the client to stay there for a moment, focusing on the feeling of safety and relief in their body, before asking them to open their eyes. It is important to show them that you understand how brave they have been to take you through this event; remember talking about this event ‘burns’ their mind. Say something like, ‘I am so impressed that you were able to make yourself do that – wow – well done for being so brave. I am glad that you were able to do it, because reliving is step number one in being in control of this memory’. If the client does not connect with the memory/emotion at this stage, you may want to do more preparation to enable connection with the emotions during hotspot elaboration and updating.

Before the session ends, with the reliving fresh in their mind, ask the client to list the worst moments (‘hotspots’) of the event (e.g. ‘when he grabbed my hair; smell of his breath, the image I had of myself being killed’). Again, these will likely map onto the patient’s re-experiencing symptoms – the therapist may also take clues of the worst moments by how visibly the patient reacted during reliving, and they can reflect with the patient on what they noticed if they are struggling to identify hotspots. Sometimes clients who have survived a rape will struggle to identify any particularly bad moments in what was a uniformly horrendous event. It might help to say something like, ‘I know the whole thing was absolutely horrendous, but it would be useful for us to try and identify those moments that were even more horrendous than others, because it is those we will target in our therapy.’

Simply make a list of all hotspots identified; like putting pins on a map. Don’t go into any more detail at this point, you will elaborate/explore the hotspots in the next sessions. Please note that it is very important that you leave time to generate this list of hotspots at the end of the reliving. The main purpose of reliving is to identify the hotspots while they are ‘fresh’ in someone’s mind. The purpose of reliving is not habituation. With this in mind, there is no need routinely to record reliving to a rape for the client to listen to at home. With some other types of trauma, listening to a recording between sessions might be helpful for the client to notice any additions or any changes in meaning/perspective. However, where there is likely to be dissociation (as is the case with rape and sexual abuse) we would not recommend doing this unless the client wants to.

Please see the following film for a demonstration of how to do reliving and identifying hotspots to a rape memory: https://vimeo.com/873645203/1e235037e0?share=copy

How to elaborate and update hotspots from a rape

Having made your list of hotspots, you and the client can now set about elaborating and updating hotspots.

Understanding hotspots

As mentioned previously, ‘hotspots’ are peaks of emotion in trauma memories which are generally also re-experienced as flashbacks, intrusive memories or nightmares. Because of memory storage problems in clients with PTSD, these hotspots have not been updated with information gained subsequently, e.g. ‘I survived’. Thus, hotspots are effectively the worst moments of the trauma, ‘frozen in time’. The client will therefore feel the same force and intensity of emotion when they re-experience the rape as they did when the rape actually occurred.

Consequently, without treatment, the client will continue to re-experience the most traumatic parts of rape repeatedly and with the same level of emotion and physical response as they did at the time. If, for example, they experienced extreme pain anally during a rape, they will continue to re-experience that again when the memory is triggered; if they thought they would suffer permanent damage to the vaginal area at the time, they will have that thought, and the emotion which accompanies it, whenever they re-experience the rape.

In order to effectively ‘process’ these trauma memories so that the client ceases to experience flashbacks, nightmares and intrusive memories, the therapist must target hotspots and the peaks of emotions therein. We can do this by gaining a thorough understanding of the emotions, thoughts, images and sensory information which sit inside those hotspots and then updating the meaning contained in them. This idea is best described in the ‘lock and key’ metaphor already discussed.

Elaborating and exploring rape hotspots

In order to understand the ‘lock’ thoroughly, we need to know what exactly is in the hotspot by exploring it. As we have mentioned above, rape hotspots can contain a number of different emotions, thoughts, images and physical sensations; our aim is to then update these hotspots and reduce the emotions or physical reactions associated with them.

To elaborate a rape hotspot, you ask the client to do a ‘mini’ reliving of it. Thus far we will have done one ‘major’ reliving of the whole rape and listed the hotspots at the end. However, we do not yet know the exact detail of each of these hotspots, which we must discover if we are to then go on to update them effectively.

As before, we ask the client to elaborate the hotspot by bringing it back to mind, and to describe in the first-person, present tense what is happening. The therapist will help the client to discover what sits within that hotspot. If, for example, the first hotspot is when the assailant grabbed the client by the throat and pushed her down onto the floor, we would guide the client slowly and thoroughly through this moment (not the whole rape) asking the same sorts of questions as we do during the initial reliving: ‘What do you see? What is running through your mind? Any images? What emotions do you feel? What’s making you feel that way? What do you feel in your body? What do you smell/taste? Do you feel pain? Is there anything else that you are noticing?’. In our experience, many people have fleeting mental images of what they fear will happen next during rape – thus it is important to ask about these too.

The therapist will continue to explore the client’s cognitions and emotions as they do the reliving of the hotspot, paying attention to non-verbal information as well as what the client is saying. For example, the client might wince or stop talking at certain particularly bad moments or speed up over crucial parts of the hotspot. The therapist must slow the client down at these moments in order to fully explore the hotspot and ultimately to uncover meanings. It is rare for a hotspot to contain only one emotion and one thought. Rather, it is helpful to consider them as ‘hot corridors’, wherein you discover more and more content as you elaborate and explore. Once you have uncovered one emotion in the hotspot, its associated meanings/images and any physical elements, it is then worth asking, ‘What other emotions are you feeling?’. You should keep going, identifying further emotions, meanings, etc., until no other emotions are identified in that hotspot.

At the end of this ‘mini’ reliving, the therapist can direct the client to open their eyes and show praise and understanding for how hard that was for the client. This is particularly important in rape because clients feel very high levels of shame about disclosing what happened to them.

It is useful at the end of the reliving of the hotspot to rate distress and/or ‘nowness’ (how much it feels like it has happening again). The scores can be taken again when updates or rescripts have been inserted, to see if they reduce.

Once this mini-reliving is completed, the client and therapist can write information gained into a hotspot chart. If possible, ask the client to do the writing themselves, as it will ensure it is in their own words and will also act as quite a ‘grounding’ exercise. For example, Sue identified the second hotspot in her trauma as the point of forced penetration. Her therapist worked with Sue to elaborate it and the chart for the second hotspot looked like this (Fig. 7):

Figure 7. Example hotspot chart after elaboration/exploration.

Updating a hotspot

Now the therapist and client have a full understanding of what sits inside the hotspot, they can set about reducing the peaks of emotion by changing the meaning associated with these peaks. This can be done in three ways:

-

Updating ‘what they know now’ and any sensory/physical information.

-

Changing the meaning itself, e.g. helping the client to see the assault was not their fault, or to reduce shame.

-

Using mental imagery techniques to enhance verbal updates or to change emotions more directly.

What they know now

As noted above, re-experiencing symptoms are essentially ‘frozen in time’ and have not been updated with information or facts that the client knows now in the present day. It can be helpful to ask the client, ‘What would have made you feel less sad/scared/angry/ashamed [depending on the emotion in the hotspot] in that moment? What, if I travelled back in time and appeared with you, could I have said that would help you to feel less sad/scared/angry/ashamed?’. If useful, therapists can use the pulse diagram to explain how we are trying to ‘shrink down’ the emotion in hotspots. If the client thought that they were going to die/never see their loved ones again, they might choose to update it verbally (‘I did not die, I am alive’) and with imagery (picturing themselves alive in the present day with their loved ones). This new information can then be added into the hotspot chart.

For Sue’s second hotspot, after discussion with her therapist, she chose the following update: ‘I know that I did not die, and my body has not been permanently damaged’. It is important for the client to generate the update as much as possible; only they really know what would have made them feel better. Therapists should try and resist the urge to suggest updates, unless the client is really struggling. If this is the case, then make sure you suggest a range of alternatives tentatively and then the client can choose the one that most resonates.

New sensory information

As with emotions, sensory information remains frozen in time. Reliving hotspots will allow client and therapist to find out what sensory elements are being re-experienced and can therefore be updated. Again, this information is put into a hotspot chart and can be updated in the following ways. As you can see, sensory updating uses the same multisensory strategies used to control dissociation:

-

Smell: e.g. the client smells semen and sweat. This can be updated by drawing attention to the fact the smell is no longer there or introducing a strong competing smell such as peppermint, ginger, eucalyptus or clove.

-

Taste: e.g. the client can taste blood in their mouth. This can be updated by drawing attention to the fact the taste is no longer there or introducing a strong competing taste such as strong mints or cough sweets.

-

Sound: e.g. the client can hear the abuser laughing or mocking her/him. This can be updated by drawing attention to the fact that the sound is no longer there or introducing a different sound such as birdsong or music.

-

Pain: e.g. the client feels the pain of penetration. This can be updated by the client looking down and seeing there is nothing there now or by introducing a different sensation such as a soft fabric held around the pelvic or genital area, or by using a vibrating cushion to provide a strong competing sensation for the pain.

-

Physical restraint: e.g. the client feels unable to move. This can be updated by drawing attention to the fact that the attacker is not here or by getting the client to engage in postures that were not possible during the trauma, such as moving arms and legs or standing up and walking around.

Please see the following film link and corresponding figure below (Fig. 8) showing how we elaborated and then updated a hotspot featuring forced oral sex with Sue: https://vimeo.com/874002913/b2f8ffa85d?share=copy

Figure 8. Hotspot chart with examples of sensory updates.

Changing the meaning itself

Survivors of rape and sexual assault are often made to feel that the assault was their fault or that they encouraged it. Indeed, rapists often tell this to their victims during the assault. This results in strong feelings of responsibility and/or shame. Once identified through reliving, these emotions and their meanings can be discussed using cognitive techniques to develop updates which reduce these emotions. Please see sections below for more information on how to work with self-blame and shame following rape. This information can form the basis of updates to help reduce peaks of shame/responsibility within the hotspot.

Following this exploration, Sue’s chart for the second hotspot looked like this (Fig. 9). Please see this film link, demonstrating how to elaborate and update this hotspot: https://vimeo.com/874556205/a6738f0f5d?share=copy

Figure 9. Hotspot chart with examples of fear and shame updates.

Imagery

Thus far, we have shown you how to update hotspots mainly with words, but there are times when that is not sufficient and imagery updates of hotspots are necessary. If a verbal update is enough to reduce emotion in the hotspot, then there is no need to do anything more. However, sometimes when the feared outcome did happen (e.g. the client feared that they would be hurt, and that did in fact happen) a verbal update is not sufficient. If this is the case, it can be helpful to refer to the pulse diagram (Figs 4 and 5) again when explaining the use of imagery to update hotspots. Therapists can explain how we can ‘shrink down’ peaks of emotions with words but that sometimes mental imagery is the only way to reduce the emotion.

There are two ways to use imagery. One is to simply ‘supercharge’ the verbal update with imagery. A client who feared they would die can have a verbal update, ‘I don’t die’ supercharged with vividly picturing themselves alive and well in the present day with their family.

The other way is to update a hotspot by using imagery rescripting. There is a growing body of evidence indicating that imagery rescripting can be an effective way of treating PTSD (Morina et al., Reference Morina, Lancee and Arntz2017; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Young, Akbar, Chessell, Stevens, Vann and Arntz2023). Imagery rescripting involves changing the ending of the hotspot so that the client can imagine getting their needs met, or having happen what they wish could have happened. For example, they could imagine that the rape was avoided and that they escaped (even though in reality the rape did happen), or perhaps exacting revenge on the rapist. In imagery, it is possible to do whatever the client wishes: they could vividly imagine becoming hugely powerful with superhuman strength, allowing them to crush the attacker and tell him how disgusting he is. This would reduce that peak of emotion, allowing the memory to be processed. The key idea in imagery rescripting is that the client comes up with their idiosyncratic new ending. It is not important whether the rescript is real or believable (in fact, often the more ‘unreal’ rescripts, seem to work more effectively). Rather, it is much more important that the rescripted memory is vivid, i.e. that the client can imagine not just what they see in the rescript, but what they hear, smell, taste, touch and do (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Salter, Parker, Murray, Looney, El Leithy, Medin, Novakova and Wheatley2023).

It is important to allow the rescript to be generated by the patient and to let them try out anything they would like. Sometimes clients do get stuck, and, in these instances, it is helpful to give a list of examples of endings other patients have tried whilst encouraging them to develop their own idiosyncratic rescript. See Box 2 for a selection that our clients have used to rescript rapes.

Box 2. Example rescripts for imagery rescripting a rape.

Imagining something is not the same as doing it. Although research has yet to answer the empirical question of whether violent rescripts lead clients to behave violently in real life, a study by Seebauer et al. (Reference Seebauer, Froß, Dubaschny, Schönberger and Jacob2014) found that violent imagery rescripts led to a decrease in negative emotions, including anger and aggressive feelings, not an increase. However, this was a non-clinical sample of students who had watched a trauma video, so these findings need replication with a clinical sample. Nevertheless, in our clinical experience, violent or aggressive rescripts lead to a reduction in anger.

Before embarking on imagery rescripting, you must help the client understand the rationale and scientific basis for using imagery rescripting, so that the process does not appear invalidating. We are clear that we are not seeking to ‘pretend’ that this horrible event did not happen; we are trying instead to reduce the peaks of emotion in the hotspot in whatever way possible, so that the client can stop re-experiencing the trauma every day. Here is how you can explain the scientific basis of imagery, which you can then use in conjunction with the pulse diagrams. (For further reading on the scientific basis of imagery, see Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Naselaris, Holmes and Kosslyn2015 and Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Geddes, Colom and Goodwin2008.)

‘People often say that imagery has a more powerful effect on your emotions than just thinking in words. Scientists have found that imagining things has a much greater effect on how you feel than thinking about them verbally. Why might this be? Recent research from neuroscience helps us to explain.

Brain scientists have used neuroimaging to investigate what is happening when someone imagines something rather than seeing, hearing, or doing it “for real”. Participants are put in a brain scanner and are either instructed to imagine something (so, for example, an angry facial expression) or are presented with the actual thing (for example, a photograph of an angry face). They have done this with imagining/seeing pictures, imagining/hearing music, imagining rotating/actually rotating an object. When they compare the brain scans, they find there is little difference; the scan of someone imagining a tune is almost the same as the scan of someone actually hearing the tune. It is as if the brain can’t quite tell the difference between you doing something and you imagining doing something.

In a recent study, researchers asked people to imagine increasingly bright lights. When we look at bright lights for real, our pupils tend to contract and get smaller, to protect our eyes. In this study, they wanted to see what would happen when people were only imagining the lights. They found that even though the people knew they were imagining the lights, their pupils were behaving as if they were actually seeing the lights; their pupils got smaller exactly in proportion to the brightness of the light they were imagining.

What is important about this study is that it shows us that knowing something is imagined and not real does not change how the brain and the body reacts to it. So, we can imagine something that has not happened and, as long as we imagine it clearly, our brain, emotions and body will react as if it is actually happening. Many of us will be familiar with this from having sexual fantasies – we know we have not secured a liaison with our favourite movie star, but while vividly imagining being with them, our heart rate increases, our body heats up and we become sexually aroused.

This research opens up a whole new avenue of things we could do to help with trauma memories. We can experiment with changing what happens in the worst moments of the trauma – imagining what you wish could have happened, that would have made you feel better. It doesn’t matter if something you imagine is real or possible, as long as you imagine it vividly, your brain will react to it as if it is real/actually happening and your mood will change accordingly.’

Updating a hotspot using imagery

The fifth hotspot Sue identified was when Jake finished raping her and said ‘Wow, that was hot!’. On exploration of the hotspot, she felt both confused and angry; why was he behaving as if the encounter had been consensual when he had clearly, violently raped her? Sue and her therapist discussed using imagery to change what happened in this moment and update the hotspot. They thought about what she could imagine that would allow her to feel less confused and to discharge her anger. After some thought, Sue said that she would like to imagine having some witnesses appear, people whose opinion could not be questioned. She chose Michelle Obama and her therapist and tried imagining them standing with her, telling him that he had violently raped her and that he was a sex offender and would be locked up. Sue and her therapist found that this reduced her confusion and helped her to discharge most of her anger. On further discussion, she decided that she would also like to see him realise that he had raped her, look horrified and beg her forgiveness. When she added this into the update, she felt satisfied.

The most important thing to remember is to take a curious, collaborative and experimental stance with your client and to try out a rescript, take some feedback and re-do it if necessary. Rescripting, and indeed updating, are not one-off opportunities. We can keep going back to see what works best for the client to help them reduce those peaks of emotion.

Please see the film link and corresponding hotspot chart (Fig. 10) below to see how we updated this hotspot with Sue using imagery rescripting: https://vimeo.com/874566712/e97b68d324?share=copy

Figure 10. Hotspot charts with examples of updates using imagery rescripting.

Guilt and self-blame

We know from research and clinical experience that interpersonal violence such as rape can cause deep feelings of shame and self-blame in our clients. Inherently, rape is demeaning, violent and debasing, it violates trust, safeness and intimacy. Sadly, many people who are raped feel ashamed and blame themselves for what happened to them, and this makes them very reluctant to talk about their experience, even in the context of therapy. Survivors of rape and sexual assault are often made to feel that the assault was their fault or that they encouraged it in some way. Indeed, rapists often say this to their victims, or it is implied by friends, family, the police or the legal system subsequently. Strong feelings of guilt and self-blame will maintain the rape survivor’s PTSD and therefore need to be targeted in treatment. In our experience, there is almost always some element of self-blame after rape, so it is really important that you look out for it and work hard to reduce/eliminate it; to be raped is horrendous, but to hold yourself responsible too is unbearable.

Therapists need to be able to reflect on their own beliefs about rape and responsibility. Have we inadvertently absorbed some of the prevalent attitudes in which women (in particular) are held responsible for behaving in a way that does not encourage rape? As mentioned earlier, therapists need to occupy a non-neutral human rights stance. Rape is a crime, there are no mitigating factors; a drunk, naked person, half-way through an evening of foreplay has the right to change their mind and not be raped. We find this metaphor about drinking tea and giving consent to be useful for helping therapists think through the issues: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZwvrxVavnQ.