I

The oil shock of the 1970s is considered one of the most momentous events in the transformation of the world economy, along with the Nixon shock (Maier Reference Maier and Hockerts2004). The fourfold increase in the oil price (from $2.90 to $11.65 per barrel between October 1973 and January 1974) caused by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) shook the foundations of capitalist economies, which until then had enjoyed a plentiful supply of cheap oil under a fixed exchange rate regime. In the longer run, the oil shock brought about huge flows of dollars to oil-rich exporters in the Middle East, which recycled their excess international liquidity to the industrialized West. This ‘petrodollar recycling’ stimulated the rise and deregulation of the Eurocurrency market as well as the liberalization of capital movements championed by American bankers (Cassis Reference Cassis2006). Those outcomes, later on, would pave the way for the rise of the neoliberal economic and political paradigm, on the one hand, and the revival of European economic integration after years of Euro-skepticism, on the other (Beltran Reference Beltran2011; Gfeller Reference Gfeller2012; Beltran et al. Reference Beltran, Bussière and Garavini2016; Bini et al. Reference Bini, Garavini and Romero2016).

This historical process, from the oil shock to the liberalization of international financial markets, is one of the most fertile fields of study in financial history. Two excellent recent works are worth citing. Selva (Reference Selva2017) analyzes petrodollar recycling in the context of the US foreign financial policy, tracing continuous attempts by the US to regain global financial hegemony. Freer capital movements, together with energy finance and development aid, strengthened US banks’ position and prepared the ‘neoliberal turn’ of the early 1980s. Altamura (Reference Altamura2016) examines the role of petrodollar recycling in the evolution of the Eurodollar market, focusing on the policy debates over the regulation of the international money market. This debate, which took place in international organizations such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), was settled by the victory of free marketeers, eager to make use of the market as an important channel for the recycling of international liquidity. Both studies stress the key role played by private international banks as well as the decision taken by public authorities, either at state level or by international organizations.

However, one important link is missing in the literature about the oil shock and its financial aftermath: Japan. In fact, the path taken by Japan before and after the shock differed from both the American and West European experiences. Japan, whose industrialization had been heavily dependent on coal energy, had quickly accomplished the energy transition from coal to oil during the 1960s (Kobori Reference Kobori2010). Since then, Japan has relied on imported oil, mainly from the Middle East, for its energy needs. The remarkable growth of the Japanese economy during the 1960s surprised the Americans and the Europeans, and Japan was allowed to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1964 (Winand Reference Winand1993; Suzuki Reference Suzuki2013). In the turmoil caused by the Nixon shock, Japan successfully abandoned the Bretton Woods system of adjustable peg and adopted a floating exchange rate, thanks to sustained global growth during 1972–3, although its overdone monetary stimulus was followed by furious inflation (Eichengreen and Hatase Reference Eichengreen and Hatase2007). In the summer of 1976, Japan, together with West Germany and the United States, was asked by the OECD Secretariat to play the role of ‘locomotive’ to trigger a growth revival in the industrialized West. As such, Japan made ‘a sound contribution to stable and non-inflationary growth in the world economy’ (Hollerman Reference Hollerman1979). The Tokyo capital market grew up ‘around government bonds that the authorities began to issue from 1975 to finance a budget deficit’ due to the oil crisis (Cassis Reference Cassis2006). On the other hand, Japan remained reluctant to deregulate its capital market until the 1980s and tried to avoid a re-evaluation of the yen up to the arrival of the bubble economy in the late 1980s (Asai Reference Asai, Yago, Asai and Itoh2015).

This article offers a Japanese perspective on the debate about the international financial system immediately after the oil shock, comparing it with the American and West European strategies. The main forum of debates to be dealt with is the OECD, especially its Working Party 3 (WP3). The WP3 was an unofficial but powerful forum for coping with problems of balance-of-payments adjustment. It naturally became one of the most important bodies for policy discussion about petrodollar recycling, international payments and global growth after the oil shock (Van Lennep Reference VAN Lennep1998; Galeazzi Reference Galeazzi2015; Yago Reference Yago, Leimgruber and Schmelzer2017). Since its foundation in 1961, the OECD had aimed at planning economic growth of the West, setting a target of ‘50 percent GNP growth in ten years for member countries’, in response to the slowdown of growth in the capitalist world of the late 1950s. Since then, managing the macro- economy with ‘target’ and ‘aims’ goals became common practice among international institutions (Schmelzer Reference Schmelzer2016; Leimgruber et al. Reference Leimgruber and Schmelzer2017). The reaction of industrialized countries to petrodollar recycling, and in particular the Japanese strategy after the oil shock, was built upon this ‘growth paradigm’ represented by the OECD.

Using the archival records of the OECD and the Bank of Japan, the article asks three sets of questions:

(1) Which recycling channels were favored by the OECD and Japanese authorities? Which market or institution played the most important role in recycling? How did Japan assess the outcome?

(2) How did OECD countries adjust the balance-of-payments disequilibrium? How did Japan, as a surplus country, react to the adjustment?

(3) How did national and international actors produce a grand scheme for global growth after the oil shock? Which role was Japan expected to play in this context?

Section II overviews the reaction of OECD and Japan to early increases in the oil price from the late 1960s to October 1973, before the arrival of the proper oil shock of 1973–4. Section III deals with the debate on petrodollar recycling from October 1973 to mid 1974, focusing on the Eurocurrency market and US banks. Section IV considers the aftermath of the crisis and the rise of ‘locomotive’ ideas in the OECD's WP3. Section V concludes.

II

The outbreak of the oil crisis caused a frenzied reaction by OECD countries and Japan. The OECD had convened a Special Oil Committee in June 1967, immediately after the end of the Third Arab–Israeli War (also known as the Six-Day War), to discuss emergency measures to be taken in oil-importing countries. The discussions, however, revealed an antagonism between the United States, which advanced the possibility of emergency oil rationing, and France, which was opposed to such a harsh measure. Japan, lying between the two opinions, kept silent: the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs instructed its representative at the OECD ‘not to support any proposals actively’. The Japanese position derived from the fact that Japan maintained a neutral stance between the Arabs and Israel in order to avoid an embargo. ‘From a longer perspective, cooperation with the US is essential’, noted the Japanese representative at the OECD, ‘from a shorter perspective, we could secure oil supply’ (Shiratori Reference Shiratori2015, p. 48).

After a pause of a few years, the oil price again entered a stormy phase in the early 1970s. How did the WP3 assess the situation? In February 1973, several months before the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War (or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War) in October of the same year, the WP3 examined a New Oil Report issued by the OECD Oil Committee, which forecasted a scenario of rising oil prices.Footnote 1 Inquiring into the oil price trend was among the institutional tasks of WP3, as rising oil costs could lead to balance-of-payments disequilibrium and a heavier reliance of industrialized countries on imported oil. The WP3 meeting brought to light some important points. First, on the basis of a set of forecasts of oil production and imports by region (i.e. North America, OECD Europe, Japan), including North Sea oil as well as domestic oil production in North America, the WP3 predicted an uneven impact of oil price rises. Its estimates, which included a serious increase in Japanese oil imports, turned out to be true. The share of oil in Japan's total imports, expressed in billions of yen, which stayed at 15.7 percent in 1973, almost doubled in 1974 (30.3 percent) and reached a peak in 1980 after the second oil shock (37.5 percent). Although this share would decrease in the 1980s owing to rising productivity and structural change of the Japanese economy (by 1989 it had fallen back to 10.2 percent), oil imports were a predominant factor for Japanese imports in the second half of the 1970s (Sugihara and Allan Reference Sugihara and Allan1993, p. 7). The WP3 forecasted also a divergence among North Atlantic economies, as the United States, still one of the largest producers of crude oil along with Venezuela, was relatively better protected against skyrocketing prices than the OECD European countries. This prediction, which was also fulfilled, would feed harsh discussions behind the scenes and a ‘conspiracy theory’ about the oil shock (Bini et al. Reference Bini, Garavini and Romero2016).

Second, and more importantly in a longer-term perspective, the WP3 Secretariat proposed a new approach to balance-of-payments aims. ‘Most OECD countries have grown used to thinking that they should aim at having current account surpluses’, but with the ‘appearance of difficulty in such reconciliation’, the Secretariat asked: ‘Is the typical OECD country now going to accept a much smaller (or zero, or even possibly negative) current balance as a norm?’ This question would further a discussion on balance-of-payments aims, which had been set as 1 percent of member countries’ GNP. The oil shock, viewed from the WP3, would influence a rethinking of growth in relation to the balance of payments.

Third, the WP3 advanced an observation that would become crucial in the coming years: ‘there are likely to be substantially greater uncertainties regarding the capital side of the account’, other than the predicted balance-of-payments deficit. ‘In practice, it will be very difficult to predict to which countries the flow will go or which forms it will take’, after a huge movement of current accounts. The report concludes that ‘Indeed, it is not only the destination of the flow of capital from oil producers, large as it seems likely to be, that would be at risk – but the stability of the entire stock, which, by 1980, might be several times the then flow’ (emphasis in the original text).Footnote 2

Against this background, what outlook did WP3 formulate in February 1973 for the Japanese economy in response to a prospective rise in oil price? ‘Looking further ahead’, the Secretariat wrote, ‘the strengthening of Japanese competitiveness is probably a continuing trend’, and ‘net investment income must also be on a rising trend as a result of the growth of Japan's net asset position’. With these observations in mind, the WP3 expressed a ‘wish to come back to the question of whether 1 percent of GNP is an appropriate current account aim’. The context was that ‘given the attractiveness of Japan as a home for investment funds, may not liberalization of inward investment be accompanied by a significant return flow, e.g. from the oil producers?’Footnote 3 This statement was important in two respects. First, it was an attempt to revise existing balance-of-payment aims of member countries to limit their surplus or deficit within a band of 1 percent of GNP. Second, once the target of 1 percent of GNP was lifted, Japan was required to increase its imports and to allow a surplus of less than the 1 percent, in return for its capital market liberalization – in fact, for accepting petrodollars. This view was reinforced by a thorough country study on Japan, presented at a WP3 meeting held in April 1973. Here the Secretariat projected Japan's current account surplus for 1973 ‘to be larger than it would have been without the new realignment’ under the Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971,Footnote 4 and joined the US in its request to Japan to allow market opening on account of trade.Footnote 5 The above discussions were representative of the attitude of OECD members toward a scenario of rising oil prices: the key point was revising the traditional approach to balance-of-payments aims, while fears of missing the target turned into criticisms against Japan for its rising trade surplus after the Smithsonian realignment.

The reaction of Japanese authorities, motivated by their traditional concern for the level of foreign reserves, was to maintain governmental regulations over capital flows (Takagi Reference Takagi2015). However, the archival documents reveal that, despite the predicted rise in Japanese oil imports, within WP3 the rest of the OECD countries expected Japan to raise imports and cut exports in this early phase of the oil crisis. In other words, both sides focused on the balance-of-payments from a short-term perspective, without taking into account inflation or macro-economic performance. The discussion analyzed in the following section, focused on the Eurocurrency market, reveals how the deepening of the oil crises made them change their mind.

III

According to the detailed study by Edoardo Altamura, the Eurocurrency market played a significant role in the recycling of petrodollars. Since the late 1960s, voices calling for the regulation of the market had become louder, especially in international fora such as the BIS and the G10. Japan, together with other major European countries, viewed with favor the idea of regulating this emerging international money market (Altamura Reference Altamura2016; Yago Reference Yago, Leimgruber and Schmelzer2017). Also in the OECD WP3, in light of the new situation caused by the Nixon shock and the transition to a floating exchange rate system, the majority was rather favorable to restricting capital movement.Footnote 6 However, after the unprecedented shock to oil prices and despite the fact that its impact was expected to vary across regions, the general attitude of the WP3 shifted toward the free-marketeers’ thinking (Gray Reference Gray2007, Reference Gray, Bini, Garavini and Romero2016; Gfeller Reference Gfeller2012).

Under increasing pressure for market deregulation, the OECD held a WP3 meeting in October 1973 to revise its recommendations, taking also into account the new estimates of the Group of Oil Experts as well as the updated balance-of-payments forecasts drafted by the Secretariat.Footnote 7 An exceptionally hot debate raged among participants, who included the US representative Paul Volcker, the WP3 chairman Otmar Emminger and the OECD official Robin Marris representing the Secretariat. Summing up the discussion, Emminger expressed a more positive view of the Eurocurrency market: ‘In so far as it was invested in an anonymous and liquid form, e.g. in the Eurocurrency market, this might on the one hand accentuate the problem of large volatile funds, but could, on the other hand, also create opportunities to finance the deterioration in the overall balance of payments of some European countries.’ The statement was important, as it signaled a move by the OECD away from a reluctant position to a more nuanced stance that emphasized the positive effect of the market in the adjustment of balance of payments.

In fact, petrodollar recycling through the Eurocurrency and the Eurocredit markets channeled a huge flow of funds toward oil-importing developing countries. This success silenced any further call for regulation of Eurocurrencies. European banks such as Barclays and Société Générale became the winners of the ‘privatization of the recycling mechanism’ (Altamura Reference Altamura2016).

How did Japan react to this change? Japanese authorities were less sanguine about the virtues of market-based recycling and found themselves rather isolated. As a resource-poor country heavily dependent on oil imported from the Middle East, Japan wished to tighten its control over capital movements, since petrodollars did not flow into the Japanese market. Koichi Inamura,Footnote 8 representing the Japanese Ministry of Finance at the WP3 meeting of October 1973, clearly stated the Japanese position. Japan ‘did not intend to ease the controls on capital inflows for the moment’, and ‘if there were any danger of capital inflows offsetting the effects of tight domestic monetary policy’, the country would ‘certainly maintain exchange controls’. The background of this blunt statement was that ‘monetary and fiscal policy in Japan were at present concerned solely with internal considerations and with the problem of dealing with internal inflation’.Footnote 9 Inamura's view stood on a notion, not clearly expressed at the WP3 meeting but rather described in his memorandum, that ‘the back flow of the oil money would mainly go to the United States’ and that in the case of Japan, such flow of oil money would be much smaller. Inamura, in his memorandum, even expressed the view that the ‘United States was rather a beneficiary’ of the situation.Footnote 10 Inamura rightly understood the consequences of allowing free market-based recycling: the flow of oil dollars would be concentrated in the United States, which would be risky for Japan's foreign reserves and financial market. The oil shock strengthened the Japanese hard position on capital controls.

Meanwhile, a pessimistic mood toward the Eurocurrency market was creeping into the international debates on the oil crisis. In February 1974, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) presented a note entitled ‘The oil situation and the euro-currency market’ at the WP3 meeting.Footnote 11 At the beginning of the 1970s, international institutions started to cooperate and exchange their documents simultaneously. The BIS report indicated that around 85 percent of foreign reserves of the oil-exporting countries were held in foreign currencies and that about a quarter of these foreign reserves had been deposited in the Eurocurrency market. Based on these figures, the BIS drew a somewhat gloomy picture with the following logic: (1) oil-importing countries with a large balance-of-payments deficit would borrow from the Euromarkets; (2) deficits would be financed by official reserves and by borrowing from other sources, especially from the US markets. In the case of the United States, the deficits could be covered by dollar liquidity, unrelated to the Euromarkets. (3) ‘The actual impact on the world total expansion of bank credit will depend on how the Euro-banks dispose of their increased deposits.’ The BIS report, which presented a clear assessment on the size and trend of Eurocurrencies, was rather pessimistic toward the future working of the market, predicting a disturbing role played by the increasing credit supply of Eurobanks.

The Herstatt crisis and the other troubles in the Eurocurrency market during the second quarter of 1974 confirmed this pessimism. The WP3 suggested that the Euromarkets ‘might be reaching saturation point’.Footnote 12 Negative signals were plentiful in the WP3 report: ‘The liquidity and profitability of many Euro-banks has been impaired by the switch of deposits away from small and medium-sized banks and the consortia banks.’ Finally, the WP3 report shared the uneasiness expressed in the BIS report: ‘From the outset, it was thought likely that the United States might emerge as a major intermediary for oil money.’ The WP3 view on this channel of petrodollar recycling was twofold: ‘This may be regarded as a desirable development in that the United States should be able to absorb large inflows of foreign funds more easily than other countries.’ However, ‘it presupposes the existence of adequate channels for the recycling of these funds on to other countries’.

The pessimism over the Eurocurrency market as a channel to recycle petrodollars was echoed simultaneously by the bankers who operated in the market. The Committee on Financial Markets, a specialized standing committee of the OECD composed of treasury and central bank representatives, held several meetings with private bankers in 1974. At the third meeting held in March 1974, the bankers unanimously expressed the view that ‘difficulties for the Euromarket as a whole were unlikely to arise’.Footnote 13 This optimistic view would be replaced by a serious sense of crisis four months later. At a similar meeting of the Committee with bankers, held in July 1974, ‘in contrast to the March meeting, there was much less optimism as to the ability of the international market to manage the bulk of the recycling problem’.Footnote 14

Now that the Eurocurrency market had become troubled, how did the Japanese authorities react? From the Japanese point of view, Eurocurrencies, and especially Eurodollars, were essential to finance growing imports. The Eurobanks, as cited above, were becoming conservative in mid 1974, and in fact demanded a premium on the lending interest rate applied to Japanese borrowers. The premium, called ‘Japan rate’ or ‘Japan premium’, was about 2 percent, which became a harsh constraint on Japan's dollar funding. Facing the Herstatt crisis in June 1974, the Japanese Ministry of Finance ordered Japanese banks to limit their short-term transactions in the Euromarket to below the amount held by the end of June 1974, and banned mid-term and long-term lending in the market by the following month. The WP3 observed: ‘Early in July [1974], Japan modified its previous policy of fully financing its current account deficit through massive short-term foreign borrowing’; ‘at the same time, they resumed depositing dollars with the commercial banks and slowed down the withdrawal of yen credit earlier extended to the banks for import financing’.Footnote 15 The Ministry of Finance, in retrospect, certified that ‘in those days, the foreign exchange authorities had a sense of crisis that the 10 billion-dollar foreign reserve was indispensable to maintaining international creditworthiness’ (2004, p. 39).

However, Japanese action in this phase could be explained not only as the classical concern to protect foreign reserves. Two events provided the context: first, the overall balance-of-payments crisis in Europe and Japan, due to the oil shock, modified the approach to balance-of-payments aims; second, a new view emerged of the role Japan could play in the oil shock situation: a growth-enhancing role, summarized a few months later in the metaphor of Japan as a ‘locomotive’ for global growth.

As for the issue of the balance-of-payments, since the second half of 1973, after the dollar depreciation the global trend and the context surrounding Japanese exports slowly changed. Unlike the optimistic forecasts of Japanese balance of payments published a few months earlier, the WP3 revised its projections: ‘The large negative impact of commodity price increases on the Japanese current balance has roughly offset the “perverse” terms-of-trade effects of this year's appreciation of the yen.’ The fall of nearly 4 billion dollars in the current surplus ‘is somewhat larger than that expected at the time of the Smithsonian, probably as a result of cyclical factors and of the special trade measures taken by the Japanese authorities’.Footnote 16 This negative view of Japan's weak balance-of-payments position turned helped the Japanese delegates in their defense of capital controls and an exchange rate policy in favor of a cheaper yen. The decline in trade surplus was partly due to the strong trade ties between Japan and the United States, reflected in the high weight of the dollar in effective exchange rates calculated by the OECD Secretariat: this amounted to 44 percent for Japan, while it was below 15 percent for Continental Europe (Germany 14 percent, France 11 percent, the Netherlands 8 percent) and stood at 19 percent for the United Kingdom; the only country with a higher weight of the dollar was Canada (60 percent).Footnote 17

What about the second issue, the so-called ‘locomotive’? The issue appeared initially off the record, at a confidential meeting of finance ministers held in January 1974. According to a report from the Bank of Japan's representative at the WP3, at the meeting ‘[Helmut] Schmidt proposed a meeting to discuss the conditions for export credit in February in Bonn, in order to avoid an excessive competition of exports among member countries’. The WP3 chairman Emminger followed: ‘Oil price increases have the effect of pumping up domestic liquidity on the monetary side and lessening demand on the material side with the transfer of monetary resources toward the high savings countries’ on the one hand, but might lead to inflation ‘with its cost-push effect’. Thus, the oil shock could bring about either a deflationary or inflationary effect.Footnote 18 This statement by Emminger depicted two opposed possible scenarios for the post-oil shock, namely cost-push inflation in industrialized countries, on the one hand, and monetary deflation as a consequence of global capital movement, on the other.

At the WP3 meeting that took place soon after, in February 1974, the Japanese delegates found themselves in a difficult position. Japanese representative Inamura noted that ‘the general feeling of the meeting was that if the oil deficit endures after next year, the deficit itself should be decreased’. All representatives of member countries criticized the balance-of-payments overview presented by the Japanese delegate, with a deficit much smaller than that forecasted by the OECD Secretariat, which meant that Japan intended to strengthen its exports more than ever. Inamura reported ‘strong wariness of the member countries to Japanese exports’. At the end of the meeting, Inamura proposed to hold the next WP3 meeting, due in April, in Tokyo.Footnote 19 At that time, Emminger's proposal was yet to be shared among the participants.

At the WP3 meeting held in Tokyo on 18 and 19 April 1974, Emminger stated that ‘a decrease in import demand of a great power like Japan would be a constraint against world inflation. The Japanese tight monetary policy in this regard coincides with the global interest.’Footnote 20 At a new WP3 meeting held on 25–26 June in Paris, the Japanese strategy was well received: ‘The way that Japan manages domestic demand on the one hand, and finances the oil deficit in the Euromarket on the other, did not meet such strong criticism.’ The major concern of the member countries shifted to the issue of where Japan would borrow outside the stagnating Eurodollar market. The Japanese delegate replied that the financing of Japanese imports would be raised mainly in the Euromarket and partly through American banks. Inamura explicitly stated: ‘this is our traditional method of import finance: we need not and cannot shift the lending to mid and long term’, as suggested by the peer members. Since ‘raising bonds overseas was in fact impossible’.Footnote 21 Given the crisis of the Eurocurrency market, Japanese delegates held to the course of turning Japan into an ‘export great power’. The Japanese reply might have seemed a stand-alone position but was supported by Emminger: his idea of decreasing imports to put an end to world inflation, and instead to finance exports with credits from the Eurocurrency market and the American banks, made Japan a future locomotive of growth.

IV

With the easing of the initial oil price upsurge, the channel of petrodollar recycling seemed to stabilize during the months that followed. The inflow of petrodollars from oil-exporting countries into the Euromarket, especially in London, was reported in an impressive table (Table 1).

Table 1. External surplus and investment of oil-exporting countries (billions of US dollars)

Source: OECD-HA, CPE/WP3(74)19, Paris, 6 November 1974, ‘Capital movements, the financing of deficits, and recycling’.

Based on these data, the WP3 evaluated the role of the Eurocurrency market as follows: ‘A large inflow of equilibrating capital into the OECD area’ has ‘offset roughly half the current account deficit of the area and greatly reduced the run-down of official reserves as well as the need to let exchange rates absorb some of the pressures’; ‘a sizeable investment of official oil funds in the United States and United Kingdom money markets’ has ‘practically financed the official settlements deficits of these two countries’; and finally, ‘the financial-intermediary (or recycling) role played by the United States and Euro-banks’, so far ‘have directly absorbed over half of the financial reflow from oil-exporting countries and financed a large proportion of the deficits of oil-importing countries’.Footnote 22

In light of this pattern of petrodollar recycling, Japan worked out a new strategy. At a WP3 meeting held in Washington on 28 September 1974, which coincided with the IMF General Assembly, the consensus among participants was that private Eurobanks were constrained as far as the investment of oil money and the risk of maturity transformation were concerned. As a consequence, the ability of the Eurodollar market to recycle was approaching a saturation point. To cope with these risks, official or semi-official borrowing would be necessary. Building on this consensus, the Japanese delegate insisted (together with other members) that ‘oil export countries would consider investing mid-term and long-term in the future’, so that ‘we should diversify the recycling channel’. However, ‘direct borrowing or direct investment’, as a method of diversification, ‘might concentrate on a limited number of countries such as the United States’. In response to this comment, the US delegate noted that ‘the foreign assets of the American banks increased by 1,500 million dollars since the beginning of the year’, and this fact ‘provides evidence of recycling to third-party countries’. Emminger commented: ‘A considerable portion of that recycling may be flowing to the Japanese banks.’Footnote 23 The Japanese strategy, as expressed at this meeting, was to diversify the channel of recycling, either through the Eurocurrency market or by the American banks and bond markets, or even with direct recycling from the oil-exporting countries.

In fact, the presence of the Japanese banks became more and more visible in 1974. Discussing the pattern of capital flows in the first quarter of 1974, the WP3 Secretariat mentioned that ‘for Japan, a substantial current account deficit of $3.3 billion was more than offset by a capital inflow of $3.5 billion. The main reason was a $4.4 billion deterioration in the short-term external position of the Japanese commercial banks.’Footnote 24 Shortly afterwards, reviewing the trend in the first half of 1974, the Secretariat reported that the external position of Japanese commercial banks, which caused an enormous capital account surplus of up to $7.1 billion, had jumped from $2.9 billion to $8.4 billion. ‘Nearly all of this inflow was due to an increase in commercial banks’ foreign liabilities in dollars, stemming from borrowing both in the US and in the Eurodollar market.’Footnote 25

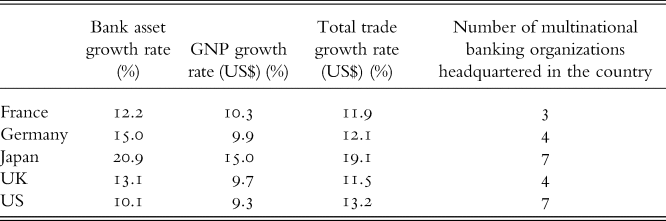

How strong was the Japanese banks’ presence? Table 2, based on contemporary published statistics, gives an impressive picture. Although Japan and the United States had in common a sustained GNP growth, the growth rate of Japanese banks’ assets was almost twice that of American banks. The table also shows that the fast growth of the Japanese economy had been triggered by trade. Using 1972 as a benchmark, data showed that the oil shock and its aftermath had brought about a successful expansion of Japanese banking and trade.

Table 2. Major bank asset growth rates (1972–86)

Source: Dohner and Terrell (Reference Dohner and Terrell1988), pp. 6, 17.

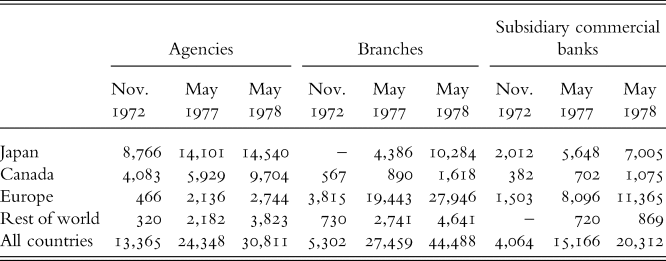

From Table 3, which summarizes foreign banks’ presence in the United States in terms of total assets between 1972 and 1978, one can see that the expansion of Japanese banks in the US market had been based more on their network of agencies rather than on branches and subsidiaries (unlike European banks). The two tables reflect their main strategies of internationalization in the 1970s: (1) to establish consortia through a collaboration with securities companies, (2) to found local subsidiaries, and (3) to manage international syndicated loans. In fact, two consortium banks were set up in London in 1970 by eight large-scale Japanese banks and four leading securities companies. Fierce competition ensued between the European and Japanese banks in search of international syndicated loans, and the Bank of Tokyo finally became the world's leading bank in loan syndications by 1978 (Igakura Reference Igakura2016, pp. 103–5).

Table 3. Total assets of US offices of foreign banks (Nov. 1972, May 1977, May 1978) (in millions of dollars)

Source: Terrell and Key (Reference Terrell and Key1978), p. 22.

As regards the adjustment process, the WP3 in late 1974 came to notice that Japan was a strong country in terms of its initial balance-of-payments position (along with Germany), but weak in terms of its current dependence on imported oil (along with France, Italy and the UK). Taking into account the ‘future dependence on oil or other energy imports’, Japan's balance-of-payments problem was predicted to be ‘particularly serious’. Moving from those premises, the WP3 set a less demanding balance-of-payments aim for Japan to take into account the fact that the oil effect could deal a hard blow to its external equilibrium.Footnote 26 In other words, the OECD now viewed the role of Japan as a trigger of international growth, thus leaving some room for a balance-of-payments deficit instead of strictly tightening the economy for the sake of the balance of payments.

A year later, in 1975, the discussion at the WP3 meeting over petrodollars had become more mature and well informed. In February 1975, the OECD Secretariat estimated a long-term reserve position of oil-exporting countries.Footnote 27 It concluded that, between 1980 and 1985, the OPEC members with a large population ‘may not only have run down the real cumulative surplus they built in the latter part of the 1970s but may also require a net capital inflow’. By this time, the OECD's view of Japan had become strongly growth oriented. When discussing the economic outlook of member countries for the near future, the general consensus was that ‘a rebound of imports of the major countries would not come about before the second half of 1975’. In this context, the Japanese delegate indicated that the Secretariat's forecast for domestic growth, ambitious as it was, was ‘consistent with their own projection’. The WP3 members, including the Secretariat, expressed their concern ‘as to whether present Japanese policy measures would be sufficient to achieve these growth rates’, and Emminger asked the Japanese delegates ‘to convey this concern to their authorities’.Footnote 28 In a confidential memorandum attached to the official record of this session, the OECD economist Marris drew the attention of the WP3 to the need to pursue a growth policy, citing the Japanese case:

Take the case of Japan that we were discussing this morning. Are we quite sure that in our judgement of the prospects for Japan, we have fully taken into account the picture we have just been discussing on the developing countries? The developing countries are extremely important markets for Japan. And we have just agreed that the volume of their imports is falling sharply. Now has all that fully been taken into account?Footnote 29

With his words, Marris wanted to emphasize that the consequences of a general decline in global economic activity for ‘locomotive’ countries should also be taken into account.

V

In the wake of, and shortly after the oil shock of 1973–4, three issues loomed large in WP3 debates. First of all, the international market for the recycling of petrodollars. Until the early 1970s Japan had camped with the advocates of a regulation of the Eurocurrency market at the OECD and other international forums. After the oil shock, major European countries changed their mind and embraced the ideas of free marketeers. Japan, which still maintained restrictions over capital movements, was isolated. The archival records show that Japan stubbornly defended its position in favor of capital control: unlike the conventional view of Japan's silence in the international arena, the Japanese delegates at the OECD were keen to maintain their steady course despite hard criticism from other members. It is worth noting that this position did not necessarily stem from Japan's alliance with the US in the context of Cold War: in fact, Japan stood midway between the Americans and the Europeans in the debate on capital movements.

The second issue was the balance-of-payments adjustment. Severely hit by the oil shock, Japan was regarded as one of the weak countries in terms of external equilibrium. The WP3 paid attention to the worsening of the balance of payments and the foreign reserve position of Japan right after the oil shock. The main concern of the WP3 countries remained the fight against inflationary pressures generated by skyrocketing oil prices. The archival records demonstrate that the concern for the balance of payments, not only for Japan but for all OECD members, led to a revision of WP3's approach to the balance-of-payments aims. This was an important paradigm change for the OECD, which tried to steer growth of industrialized countries through planning and long-term aims setting. The softening of the aims approach under the impact of the oil shock would also suggest a reconsideration of the aggregate demand management supported by Keynesian economics, until then very influential within the OECD. The revision also implied a more explicit criticism of Japan's trade surplus.

The third issue, and the most important one for our research question, was the management of global growth. When the Japanese economy quickly regained sustained growth, other WP3 members did not hide their concerns for the role of Japan as an export giant, and criticized its exchange rate for being undervalued. However, in 1975, their view changed, and they began to expect Japan to act as a trigger of international growth. Together with Germany and the United States, the Japanese economy was considered as one of the ‘locomotives’ that could lead the revival of economic growth in the West. In this context, the major concern of the WP3 shifted from how to tame Japanese exports to how to get Japan to import more, especially from the developing countries. The records of the Bank of Japan archives reveal that this change was initiated, at least within WP3, by Otmar Emminger. His view was that petrodollar recycling could have either an inflationist or a deflationist impact on the world economy. The role Japan was expected to play, following Emminger's proposal, became very demanding: to contribute to the global fight against inflation by keeping higher domestic interest rates, to enhance growth in the developing world by importing more from relatively poor countries, and finally to trigger international growth. Acting collectively as a strong banker, Japanese bankers and authorities diversified the channels for raising the necessary dollar funding.

Did Japan live up to the role it was expected to play after the first oil shock? The answer is yes: it became a ‘locomotive’ of world growth, together with Germany and the United States. While most European countries were fighting against inflation with higher domestic interest rates, Japan helped trigger a growth revival of industrialized countries. Japanese authorities’ concerns over the scarcity of foreign reserves disappeared, the pessimistic view of a weak country heavily dependent on oil from the Middle East was overcome, and Japan even accepted the appreciation of a ‘strong’ yen as a tool for balance-of-payments adjustment. The start of a ‘locomotive’ policy was intimately connected to the search for solutions to petrodollar recycling, the balance-of-payments adjustment and global growth management. The process was much more complicated than the conventional view based on the ‘American hegemony’ (Spiro Reference Spiro1999). Japan played (and was forced to play) a more prominent role in the world economy during and after the oil shock. An important point to reflect on here is that the whole process strengthened Japan's approach to capital movements, exchange rate management, state-led growth orientation and international banking strategies. In this sense, the ‘Neoliberal turn’ (Selva Reference Selva2017) did not reach Japan. The oil shock and its aftermath prompt us to rethink the role of Japan in contemporary financial history.