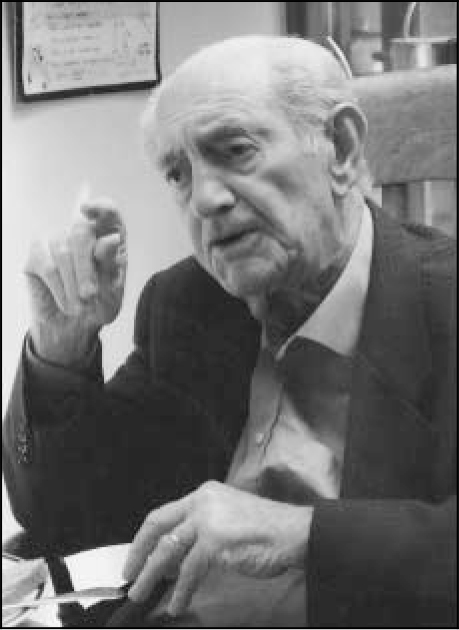

On 17 November 2011 Henry Rollin celebrated his 100th birthday, probably the first UK psychiatrist to do so. He qualified in 1935, rose to the rank of Wing Commander during the Second World War, and for 25 years worked at Horton Hospital, Surrey, followed by 10 years as forensic psychiatrist at the Home Office. For the past 30 years he has been Obituaries Editor for The Psychiatrist.

Photo © Bruno Schrecker, famous as a cellist and a member of the Allegri String Quartet.

There can be few academic journals which have a centenarian editor. It seemed appropriate for The Psychiatrist to mark this occasion, so I visited Henry in his own home and interviewed him. He was surrounded by birthday cards, with that from Her Majesty taking pride of place on the mantelpiece. Our discussion centred on Henry's reflections on the past and ideas for the future. Clearly an hour's interview cannot be comprehensive, so it built on biographical information already available Reference Rollin1,Reference Rollin2 and Professor Peter Tyrer's recent tribute to him. Reference Tyrer3 It aimed to focus on themes relevant to current psychiatric practice.

Enlightenment, old age and mental hospitals

Henry thought that enlightenment, meaning the dignity and humane treatment of patients, is less prominent now than it was in 1948 when the National Health Service was established. ‘I think it has gone back,’ he said, ‘we need more enlightenment, that is, appreciation of the difficulties of being old, of being mad and of being old and mad… The problem is that the people working with old people have no comprehension of the problems of being old. I am getting old so I speak first hand. When you get old you develop quirky sorts of interests and they have to be attended to.’

What else, how should we treat older people?

‘Like human beings.’

Does that mean that they are not treated like human beings?

‘Absolutely. That is not the generality of people who work with old people. But there are too many who have no patience who should never have been allowed to treat or handle old people. They are very fragile…At one time old people were ignored, bloody nuisance, wet himself again, abuse them, mock them.’

That has improved?

‘Yes, I think so. Enlightenment… older people, human beings – they have interests – they have sensitivities – all of them have got to be respected.’

Enlightenment is also linked to community care. In Henry's autobiography he commented that he could not see ‘how such reliance could be placed on the concept of “community care” when no fieldwork had been done to prove that the community did care’. Reference Rollin2

How do you feel about that now?

‘I am just as sure of it as I was when I wrote it.’

Do you think the community does care?

‘I do not think they care a damn.’

Do you think there is any such thing as care in the community?

‘If it is done properly, yes.’

Do you think community care is done properly?

‘No, I don't.’

What should we be doing to improve it?

‘Rebuild our mental hospitals.’

That idea was also the subject of a recent Maudsley debate on whether the reduction in beds for mental illness has gone too far. Reference Tyrer and Johnson4 Influences on the closure of the mental hospitals have long been debated. The Whiggish historical view of ‘progress’ emphasised links to social ideals, psychopharmacology, the Mental Health Act 1959 and comprehensive services in the new district general hospitals. Reference McKeown5 Others thought that community care would be cheaper than maintaining vast institutions. Henry's view was different:

‘Enoch Powell [Minister of Health 1960–1963]…I think he was a vandal. I wonder if psychiatry will ever recover from the wholesale destruction of the mental hospitals. There was a time when I was at my peak, we did a very good job at Horton, for example, with employment… My motto was “Unemployment is a dangerous occupation”.’

So there were good things about the mental hospitals?

‘Pre-Powell. Indeed there were. I was appalled. The destruction of the mental hospitals, the burning of Rome, there has been nothing greater than that…It was Powell's determination, willy-nilly.’

Why was he so determined?

‘Because he was a crank.’

Henry acknowledged that there had also been inadequate care in some mental hospitals, like the distressing and ‘awful sight of a living menagerie’ at the 2000-bed Caterham Mental Hospital Reference Lindsay6 where he worked in 1939.

Medication

Henry remembered the early 1950s when the first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was introduced. Side-effects were frightening: Reference Seville7 ‘It was a very dangerous drug, anyone who touched it was getting dreadful eczema, so much so that some had to stop nursing altogether. This was very, very shocking. It was nothing to do with the drug per se, some other matter had crept into it.’

Henry expressed sadness when he spoke of the limited progress in knowledge about the brain and effective treatments: ‘If it had been as effective as they had claimed it to be, then we would all be losing our jobs. It was not the “-biotic”. We are still waiting for that.’

Respecting one's teachers

Henry commented on some of his teachers at the Maudsley in the 1940s: ‘We had the most brilliant teaching from Germans [refugees]. Eric Guttmann – he was a nice man. A gentleman. He was so popular.’

He did all those experiments on mescaline and amphetamines…

‘That was his hobby! Brilliant teacher!’

What was Willy Mayer-Gross like?

‘Another first-class asset.’

And how would you sum up Aubrey Lewis?

‘No matter whatever, he was well worthwhile, he was a genius, he really was.’

As teachers, we must remember that the memories and inspiration we create last a lifetime.

Speaking his mind

Henry did not fear being outspoken. At times he said his comments were ‘outrageous’, and he described himself ‘a rebel’. For example, about psychoanalysis he said:

‘I have no time for psychoanalysis, none at all. At the time when I was in America [1950s], psychoanalysis was at its height. You could not get a job as a janitor without some form of psychoanalysis. I thought it was nonsense. I have not the slightest doubt that the mere fact that these people spent time with other people discussing their troubles was good, but whether it was therapeutic was another matter.’

At times he ran into conflict with hospital management, especially when he thought they were imposing administrative changes which were not in the interests of patients. In a letter to the BMJ about hospital boundary changes in 1974 he stated: ‘Doctors and their patients… are not packets of soap-flakes that can be moved from one shelf to the next shelf or from one shop to the next shop with impunity…Do I sound disenchanted, disillusioned or even a little paranoid? I am. I bloody well am.’ Reference Rollin8 When we discussed this, he laughed heartily and added proudly: ‘That shook the establishment! No one else had the nerve to say anything as outspoken as that.’

Henry now

Peter Tyrer speculated recently: ‘I do not know what is in Henry's mind, but I'm sure he is actively organising something of importance.’ Reference Tyrer3 Henry commented, ‘I always am!’ His birthday party was at Gaby's Deli, a café in central London currently under threat of closure; Henry is actively involved in the campaign to save it. He also has new experiences to look forward to; his first grandchild was born on his 100th birthday. When asked about continuing to edit the obituaries, he replied: ‘Oh yes! Until I am kicked off! I love writing. I have been writing all my life.’

When I asked Henry for his postcode for future correspondence (no – not to check his long-term memory!), he clarified the last two letters as ‘H for Henry, Y for Yobbo’ with a laugh and a twinkle in his eye. As I left, another visitor arrived. I wondered whether Henry would have time to read The Times, as yet unopened.

So, many happy returns Henry. And perhaps for a wise centenarian and leader with rebellious traits, one might add a traditional Jewish birthday greeting: ‘To one hundred and twenty!’ – longevity like Moses.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.