No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 February 2009

1. A/CONF.183/9.

2. Document provided by Burrus Carnahan, Professorial Lecturer in Law, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. Please note that the document contains internal cross-referencing to footnotes, although some of the cross-references are incorrect. Thus, the first cross reference cited is as in the original document. The footnote cited in brackets is the cross-reference to footnotes in this section.

3. The projectiles are produced by NAMMO (Nordic Ammunition Company) of Norway, its designer, and Fabrique Nationale of Belgium. The projectiles are loaded by ammunition manufacturers in each of the four nations.

4. Both meetings of experts were hindered by ICRC officials' lack of basic knowledge of weapons and how they work or are employed, their lack of historical and basic military knowledge to provide them a useful point of reference, as well as ICRC use of unconfirmed anecdotal information to sensationalize its assertions. For example, it was alleged that cal. .50 ‘pistols’ existed, and that subject ammunition could be used in combat for close-range, anti-personnel purposes. The ICRC representatives were informed that there are some custom-made, single-shot pistols that are expensive, rare and extremely uncomfortable to shoot. No cal. .50 (12.7×99mm) military pistol exists, nor is there any known military requirement for such a weapon. NAMMO representatives also emphasized controls it and the other nations exercise in export and issuance of subject ammunition.

5. The M82A1 was subject to a recent legal review by this office; see DAJA-IO Memorandum to Staff Judge Advocate, U.S. Army Special Forces Command (7 September 1999), Subject: Barrett M82AI Cal. .50 Sniper Rifle; Legal Review. Data collected for that review confirmed that the weapon's primary purpose is to engage anti-materiel targets. It also confirmed the legality of the weapon.

6. The Raufoss Multipurpose technology is used in a number of calibers. Subject round is the smallest.

7. From the outset the ICRC incorrectly labeled the issue as ‘exploding bullets’, showing a predisposition to condemnation before it had a working knowledge of subject munition. Its test report referred to ‘explosions’ of some projectiles; its test photographs of the glycerin soap blocks established that the projectiles had not exploded. It was advised by the experts that subject munition (a) is a projectile, not a bullet, and (b) that it deflagrates rather than exploding. Deflagrate is defined as ‘to burn rapidly with intense heat’. The cal. .50 Raufoss Multipurpose munition relies upon a pyrotechnic initiated explosive to fragment the projectile rather than a mechanically-induced detonation; hence use of deflagration. In contrast, detonate means “to explode with sudden violence.” Detonation provides a faster reaction than deflagration, with a much higher (ten times or more) reaction velocity. With deflagration, the reaction produces fewer but larger fragments, moving forward in a cone of approximately twenty degrees. A detonation would break up the projectile into smaller fragments with a higher velocity, with wider dispersion. Because of the emotional and pejorative nature of the term, the ICRC persists in its misleading characterization of the issue as one concerning “exploding bullets.”

8. The undersigned headed the U.S. delegation. Other U.S. attendees were Colonel Martin S. Fackler, MC, USA (Retired), regarded as a leading expert on wound ballistics and father of the modern wound ballistic test (as used in Thun), and Charles F. Buxton, Senior Engineering Technician for Navy Small Caliber Ammunition, Naval Surface Warfare Center, Crane, Indiana. Government officials and industry experts from each of the manufacturing nations attended. Two ICRC observers were present.

9. One shot (#8) was fired into blocks 15×25×25×50, with 2cm between the blocks. Photographs of all test shots are in the undersigned's possession.

10. The August 1998 ICRC test was of 1988 NAMMO-manufactured projectiles loaded with PETN. The projectiles were assembled in Fabrique Nationale cases. (The ICRC incorrectly identified the rounds as manufactured in their entirety by Fabrique Nationale.) Later projectiles utilize RDX or HMX, more stable explosives. Quality control measures taken over the past decade further diminished premature deflagration.

11. Article 36, 1977 Protocol 1 Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, provides that “In the study, development, acquisition or adoption of a new weapon, means or method of warfare, a High Contracting Party [government of State Party to Additional Protocol I] is under an obligation to determine whether its employment would, in some or all circumstances, be prohibited by this Protocol or by any other rule of international law applicable to the High Contracting Party.” Although the United States is not a State Party to Additional Protocol I, the U.S. weapons review program (references a. and b.) preceded Additional Protocol I and meets this requirement. While (for example) Article 9 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 12 August 1949 declares that “The provisions of the present Convention constitute no obstacle to the humanitarian activities which the International Committee of the Red Cross … may perform,” even that provision is qualified by the phrase “subject to the consent of the parties to the conflict concerned.” Article 81, paragraph I of Additional Protocol 1 limits the ICRC to assistance from parties to a conflict “in order to ensure protection and assistance to the victims of conflicts,” that is, military wounded, sick or shipwrecked, enemy prisoners of war, and interned civilians or civilians in occupied territory. See Bothe, Partsch & Solf, , New Rules for Victims of Armed Conflicts (1982), p. 496Google Scholar, a legislative history of Additional Protocol I produced by three participants. The ICRC commentary on Additional Protocol I agrees with this analysis; see Sandoz, Swinarski & Zimmennan, , eds., Commentary on the Additional Protocols of 8 June 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 (1987), pp. 938–939Google Scholar. Neither recognizes or claims ICRC authority with respect to issues related to weapons or war fighting.

12. ICRC proposals seeking a mandate at the XXIVth (1986), XXVIth (1996) and XXVIIth International Conferences of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (1999) were not endorsed by governments. The XXVth Conference (1991) was cancelled.

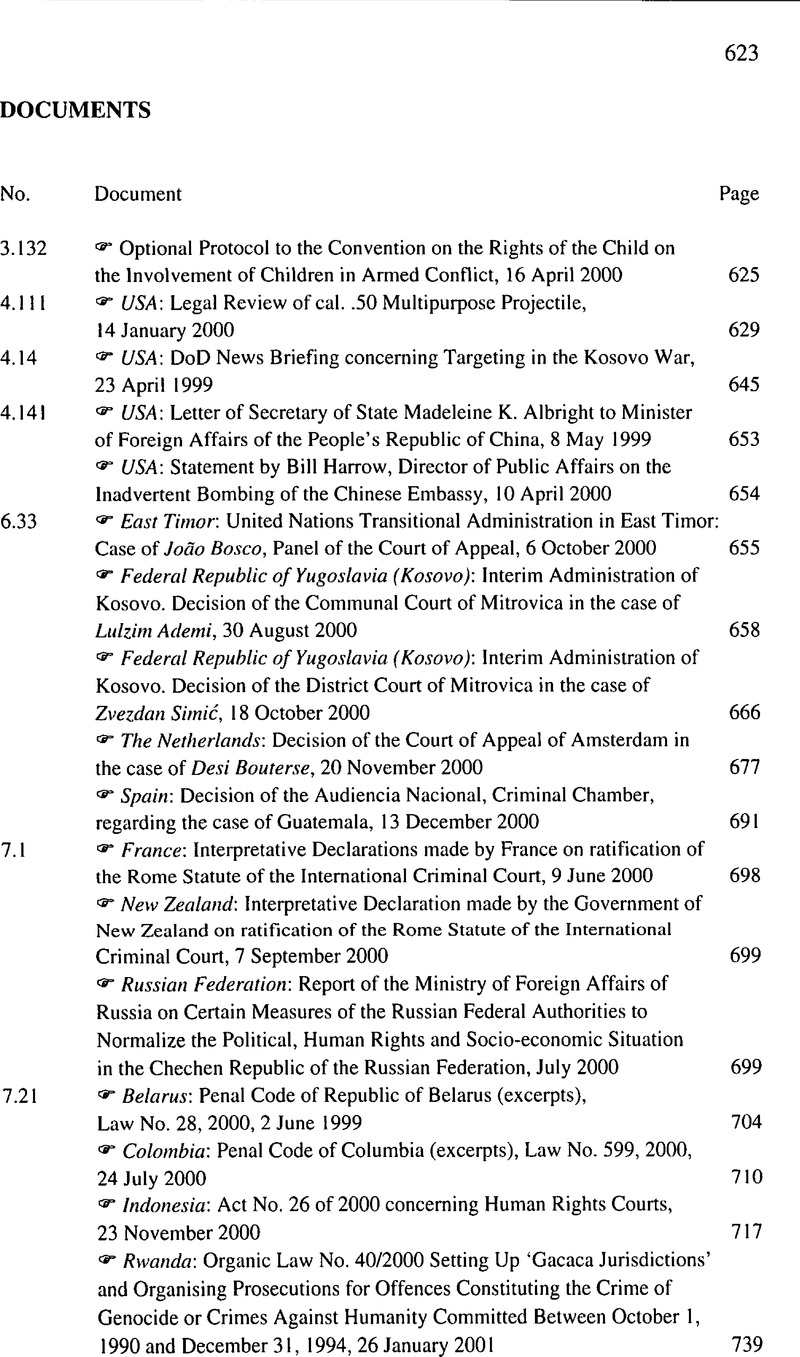

13. Manufacturer's test data provided the following comparison:

Penetration data of cal. .50 Raufoss Multipurpose round relative to the M8 API

14. An historical sununary [sic] and technical description of the cal. .50 Raufoss Multipurpose round can be found in Strandli, , “Multipurpose Ammunition,” Military Technology (09 1991)Google Scholar; and Frigiola, , “.50 Caliber Mulit-Purpose [sic] Ammunition,” Very High Power (1998, #2)Google Scholar.

15. Much of the early record of explosive bullets is from the Imperial War Museum's Pilford, Neil, in his “Explosive Bullets,” in Handgunner (04 1990), pp. 25–38Google Scholar.

16. Grant, , I Personal Memoirs (1894), p. 316Google Scholar. Also cited in Spaight, , War Rights on Land (1911), pp. 78–79Google Scholar, and Winthrop, , Military Law and Precedents (2°d ed., 1920), p. 785Google Scholar. Grants often-quoted complaint did not specify whether Union soldier injuries were intentional or incidental to Confederate attack of Union materiel targets. Nor did he mention the Union Army's original acquisition and employment of the Gardiner projectile, or anti-personnel use of Gardiner rounds by Union forces. For the latter, see Hayden, , “Explosive and Poisoned Musket or Rifle Balls,” Southern Historical Society Papers (01 1880), Vol. 8, pp. 28Google Scholar, and Austerman, , “Abhorrent to Civilization,” Civil War Times (09 1985), pp. 36–40Google Scholar. As the 18th President of the United States (1869–1877), Grant did not endorse the prohibition contained in the St. Petersburg Declaration, discussed infra.

17. Bordwell, P., The Law of War Between Belligerents (Chigago, Callagham 1908), p. 87Google Scholar; and St. Petersburg conference report summary, p. 460.

18. A detailed summary of the conference prepared by Dr. Feodor de Martens was provided by Dr. Jiri Toman of the Henri Dunant Institute, Geneva, and translated by Lieutenant Colonel Eva M. Novak, JA, USA. During the first experts meeting (March 1999), ICRC officials admitted that they did not possess nor had they examined the legislative record for the St. Petersburg Declaration, even though they repeatedly referred to the declaration.

19. Participating nations were Austria, Bavaria, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Persia, Portugal, Prussia, Russia, Sweden and Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, and Wurtemberg. The United States declined to attend or to agree with the Russian proposal to limit explosive projectile use. The degree to which each signatory state was legally bound by the declaration is limited, if at all, as none subsequently ratified or acceded to it. For example, the delegates from Belgium and Turkey indicated that each was under instructions to sign the “protocol” proposed by Russia, but not to go beyond signature in obligating their respective governments. The delegate of Wurtemberg stated that he was authorized to sign the protocol, subject to ratification by his government.

20. Article 13(e) of the 1874 Brussels Conference International Declaration Concerning the Laws and Customs of War, noted infra, made an express distinction between “arms, projectiles or materiel calculated to cause unnecessary suffering” and “projectiles prohibited by the Declaration of St. Petersburg of 1868.”

21. In the 1899 debate preceding adoption of the Hague Declaration Concerning Expanding Bullets the United States delegate proposed (as an alternative to the language ultimately adopted) prohibition of the “use of bullets which inflict uselessly cruel wounds, such as explosive bullets and, in general, every kind of bullet which exceeds the limit necessary for putting a man hors de combat …” Supported only by the United Kingdom, the proposal was rejected in lieu of language prohibiting “bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body” only. A similar proposal offered by the United States at the second Hague Peace Conference (1907) also failed. Hull, , The Two Hague Conferences (1908), pp. 181–190Google Scholar.

22. See, e.g., Mets, The Evolution of Aircraft Guns, 1912–1945 (1987), pp. 37–38, 48–52; Huon, Military Rifle & Machine Gun Cartridges (1988), pp. 188–189, 300–302; Labbett & Mead, .303 inch – A History of the.303 Cartridge in the British Service (1988), pp. 85–91, 105–138; Labbett & Brown, British .303 inch Ammunition (Special Loadings, 1915–1945) (1994), pp. 724; Dent, German 7.9mm Military Anununition [sic], 1888–1945 (1990), pp. 11–36; and Hackley, Woodin and Scranton, History of U.S. Military Small Arms Ammunition, Vol. 1, 1880–1939 (Revised ed., 1998), pp. 153–154, 167, 174, 176–184. There are allegations of World War I Russian use of exploding small arms ammunition in Panning, “Effects and Evidence of Soviet Infantry Explosive Ammunition,” The German Military Doctor 7, 1 (January 1942), p. 20 (tr. by Paul Siebold, 1990).

23. See Spaight, , Air Power and War Fights (1924), pp. 168–194Google Scholar.

24. Spaight, id., p. 187

25. Spaight, , Air Power and War Rights (3rd ed., 1947), pp. 209–212Google Scholar.

26. Spaight, id., p. 213; Mets, pp. 74–77, 115–116; Labbett & Mead, .303 inch, pp. 139–142Google Scholar; and Labbett & Mead, British 20mm Hispano Ammunition (1996)Google Scholar. Larger calibers, such as 75mm, are beyond the scope of this review, as projectile weight is greater than the 400-gram limit of the 1868 St. Petersburg Declaration.

27. Mets, pp. 198–199; Labbett & Mead, British 20mm Hispano Ammunition, p. 9, 14–20Google Scholar; Labbett & Mead, .303 inch, pp. 91103, 118–127, 143, 148Google Scholar; Kent, pp. 44–56, 68–70; and Hackley, , Woodin & Scranton, History of Modern U.S. Military Small Arms Ammunition, Vol. II, 1940–1945 (1978), pp. 7783, 94–96, 97–114Google Scholar. Huon, supra n. 20[23] pp. 114–115, 103–105.

28. Labbett & Mead, supra n. 18 [23], pp. 105–149; Kent, , German 7.9mm Military Ammunition (1990), pp. 53–56Google Scholar; Huon, id, pp. 49, 114.

29. Kent, pp. 68–70, Appendix III, p. 3; Huon, id., pp. 122, ; and Senich, , The German Sniper 1914–1945 (1982), p. 109Google Scholar. Kent notes that as early as 1938 the Germans were careful to stress the training and observation purposes of the [B. Patrone] round to prevent international protests that it was designed for use against troops (p. 69). Subsequently it was used in Luftwaffe aircraft and, as indicated, by German snipers.

30. Panning, supra n. 6 [23], p. 20; and Kent, id., Appendix III, p. 3.

31. Senich, , The Complete Book of U.S. Sniping.(1988), pp. 133–157Google Scholar; Strandli, , “Cal. .50 Browning Machine Gun and the Ammunition through 75 Years — An Historical Review” (10 1996)Google Scholar; and Strandli, , “Cal. .50 Machine Gun — 75 Years — A Review of Ammunition Types, 1932–1996” (10 1996)Google Scholar.

32. Senich, id.; and Chandler & Chandler, Death from Afar, vol. I (1992, pp. 14–23)Google Scholar;II (1993, pp. 49–51); and Plaster, , The Ultimate Sniper (1993), pp. 225–227Google Scholar.

33. Hackley, Woodin and Scranton, supra n. 20[23], pp. 115–177; and Huon, supra n. 20 [23], pp. 334–337.

34. See Huon, id., pp. 211–213 (12.7×81mm Breda, used and manufactured by Italy, Japan, Spain and Hungary, with tracer, incendiary, armor piercing, armor piercing-tracer-incendiary, armor piercing-incendiary, incendiary-tracer, observation, explosive, explosive-tracer, explosive-incendiary, and explosive-tracer-incendiary projectiles), pp. 215–216 (12.7 × 108mm, developed by Russia in 1930 and used by Russia, China, Czechoslovakia, Egypt, France, Iraq, Yugoslavia, North Korea, Poland and Syria, with armor piercing, armor piercing-incendiary, armor piercing-incendiary-tracer, and explosive-incendiary projectiles), pp. 217–219 (13 × 64mm, designed by Rhein-mettal in Germany in 1933 and used during World War II by German, Finnish, Italian, Japanese and Rumanian forces, and subsequently by Swiss and Spain, with explosive-incendiary day tracer, explosive-incendiary night tracer, armor piercing day tracer, armor piercing night tracer, armor piercing-phosphorous-incendiary, armor piercing, incendiarytracer, and explosive [Switzerland only] projectiles), and pp. 234–236 (14.5 × 114mm, a 1941 Russian design subsequently manufactured in and used by Russia, Poland, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, China, North Korea, Egypt, Iraq and France, with armor piercing-incendiary, armor piercing-incendiary-tracer, incendiary-tracer, and explosive-incendiary). Each of these projectiles weighs substantially less than 400 grams.

35. Pagel, , “Some Notes on the Development of the Hi-Explosive Fifty Caliber Cartridge,” Very High Power (1993, #4), pp. 15–20Google Scholar. The M48 spotter-tracer round series was introduced in 1953 for the 106mm recoilless rifle for use primarily against armor and other hard targets; Pagel, , “The ‘Other’ Fifty Caliber Rounds,” Very High Power (1996, #4), pp. 21–39, at 24Google Scholar. “Tracer” is listed as a category, as there have been numerous variants; Pagel, , “New U.S. Military Versions on the .50 BMG Cartridge,” Very High Power (1997, #4), pp. 15–24, at 15–20Google Scholar.

36. Huon, supra n. 18 [23], pp. 34, 94, 100–101; Hughes, , The History and Development of the M16 Rifle and its Cartridge (1990), pp. 149–150Google Scholar.

37. For example, a 1990 paper prepared by two representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross refers to basic humanitarian principles stated in the prefatory language of the St. Petersburg Declaration, but does not suggest that the 400-gram prohibition remains in effect. See Doswald-Beck, and Cauderay, , “The Development of New Anti-personnel Weapons,” International Review of the Red Cross (11-12 1990), pp. 565–576Google Scholar. Similarly, in an international symposium held in St. Petersburg 1–2 December 1993 in celebration of the 125th anniversary of the St. Petersburg Declaration, no speaker suggested that the 400-gram limitation remained in effect. International Committee of the Red Cross, The 1868 Declaration of St. Petersburg (ICRC, 1994)Google Scholar. In the March 1999 meeting of experts, Ms. Doswald-Beck confirmed that the ICRC agrees with the U. S. view that the 400-gram weight limit in the St. Petersburg Declaration is obsolete.

38. See, e.g., Palmer, , “Survey of Battle Casualties, Eighth Air Force, June, July and August 1944,” in Beyer, , ed., Wound Ballistics (1962), pp. 557, 594–597Google Scholar.

39. Prefactory paragraph of the St. Petersburg Declaration states that the object of war “would be exceeded by the employment of arms which uselessly aggravate the sufferings of disabled men, or render their death inevitable” and “That the employment of such arms would, therefore, be contrary to the laws of humanity.”

40. In addition to the discussion of anti-personnel land mines in footnote 39 [42], the wounding effects of hand grenades landing on or near an individual soldier, the Claymore (a weapon expressly recognized as lawful in the Amended Mines Protocol, UNCCW), and mortar or artillery rounds that impact immediately adjacent to an individual soldier are likely to produce substantially greater wounds than subject munition even were it to function inside the body.

41. This statement uses the term projectile rather than munition in acknowledgment of the equally considerable practice of nations in use of anti-personnel land mines, many of which detonate on impact with the human body. The legality of antipersonnel land mines was confirmed by Protocol II to the UNCCW, which was improved and updated as the Amended Mines Protocol at the first UNCCW Review Conference in 1996. The subsequent Ottawa Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (18 September 1997) banned antipersonnel land mines for States Parties to it. It did so on the basis of the hazard to civilians from the indiscriminate effect of their irresponsible use, primarily in some internal conflicts in the least developed or less-developed nations. Neither the Amended Mines Protocol nor the Ottawa Convention concludes that anti-personnel land mines violate the prohibition of weapons calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.

42. The 1899 text used (in English translation) “of a nature to cause,” which also is used in Article 36, Additional Protocol I. Neither calculated to cause or of a nature to cause supports the very strained ICRC interpretation. See Bothe, Partsch and Solf, , New Rules for Victims of Armed Conflicts: Commentary on the Two 1977 Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, pp. 196–197Google Scholar. Support for the ICRC argument cannot be found in its own legislative history of Additional Protocol 1 (see Sandoz, , et al, eds, Commentary on the Additional Protocols [1987], pp. 399–410Google Scholar), or its own literature (see, e.g., Meyrowitz, , “The Principle of Superfluous Injury or Unnecessary Suffering,” International Review of the Red Cross [03-04 1994])CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

43. Statement of Colonel (later Major General) Sir David Hughes-Morgan, British representative to the Conference of Government Experts on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons, Lucerne, Switzerland, 24 September to 18 October 1974. The British statement was supported by the United States representative. It gained further support in the 1974–1977 Diplomatic Conference that drafted and adopted Additional Protocol I. See Bothe, Partsch and Solf, id.

44. Document provided by Burrus Carnahan, Professorial Lecturer in Law, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. and Ronald D. Neubauer, Associate Deputy General Counsel, Department of Defense, Office of the Deputy General Counsel (International Affairs)

45. Document provided by Burrus Carnahan, Professorial Lecturer in Law, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

46. Document provided by Jonathan Cina, Legal Advisor, Serious Crimes Office, UNTAET.

47. Document provided by Christer Karphammar, International Judge of the Communal Court of Mitrovica. Official translation by staff of the Interim Administration of Kosovo.

48. Unofficial translation by Peter Kell for the TMC Asser Institute.

49. Elrono. AA8395 (http://www.rechtspraak.nl).

50. Art. 12 of the Code of Criminal Procedure reads: ‘1. If an offence is not prosecuted or the prosecution is not pursued, a party having a direct interest may submit a written complaint about this to the Court of Appeal within whose jurisdiction the decision not to prosecute or not to pursue the prosecution has been taken. 2. A party having a direct interest is deemed to include a legal entity which, according to its objects and as evidenced by its actual work, represents an interest that is directly affected by the decision not to prosecute or not to pursue the prosecution.’

51. Art. 5(1)(2) reads: ‘Dutch criminal law is applicable to Dutch nationals who commit, outside the Netherlands, an offence regarded as an indictable offence in Dutch criminal law and punishable under the law of the country where it was committed’.

52. UNTS p. 3; ILM (1967) p. 360: Trb. 1969 No. 100.

53. Art. 15 reads: ‘1. No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time when the criminal offence was committed. If, subsequent to the commission of the offence, provision is made by law for the imposition of a lighter penally, the offender shall benefit thereby. 2. Nothing in this article shall prejudice the trial and punishment of any person for any act or omission which, at the time when it was committed, was criminal according to the general principles of law recognised by the community of nations’.

54. Art. 16 reads: ‘No offence shall be punishable except by virtue of a prior law’.

55. Stb. 1988. No. 478.

56. The complainants had previously submitted a complaint under Article 12 of the Criminal Code in 1996. The Court of Appeal dismissed the complaint on that occasion because the Public Prosecution Service had not yet taken a final decision on whether or not to prosecute. After the Public Prosecution Service had informed the complainants on 13 May 1997 that it had definitely decided not to prosecute, they once again filed the present complaint.

57. Elrono. AA8424 (http://www.rechtspraak.nl), NJ (2000) No. 266, summarized in DD (2000) p. 756. The Procurator General at the Court of Appeal had for this reason advised against bringing criminal proceedings.

58. UNTS p. 85; ILM (1984) p. 1027; Trb. 1985 No. 69.

59. Elrono. AA5014 (http://www.rechtspraak.nl). Professor Dugard was appointed by decision of 26 April (Elrono. AA8429, http://www.rechtspraak.nl). He was requested to reply before 15 July.

60. Elrono. AA8427 (http://www.rechtspraak.nl).

61. UNTS p. 11. Art. 3 reads: ‘All Netherlands nationals of full age who were born in Surinam and whose domicile or place of actual residence is in the Republic of Surinam on the date of the entry into force of this Agreement shall acquire Surinamese nationality’.

62. Dugard advances the following argument in support of the distinction: ‘[ 1]’.

63. Art. 94 reads: ‘Statutory regulations in force within the Kingdom shall not be applicable if such application is in conflict with provisions of treaties or of resolutions by international institutions that are binding on all persons’.

64. Available online in Spanish at http://www.pangea.org/impunitat/ or at http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/guatemala/doc/espana.html. Translation courtesy of Amnesty International, London.

65. Document and unofficial translation provided by Oleg Starovoitov, (lecturer in public international law at the Faculty of International Relations at Belorussian State University, Minsk, Belarus.)

66. Document and official translation provided by Dr. Rafael Prieto Sanjuán, Professor of International Law and International Humanitarian Law at Externado University of Colombia, Bogotá.

67. Law provided by Aloys Habimana, Project Coordinator for the Documentation and Information Center on Genocide Trials, a project of the Rwandese League for the Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (LIPRODHOR).